|

|

Bosón de Higgs

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

El bosón de Higgs o partícula de Higgs es una partícula elemental propuesta en el Modelo estándar de física de partículas. Recibe su nombre en honor a Peter Higgs quien, junto con otros, propuso en 1964, el hoy llamado mecanismo de Higgs, para explicar el origen de la masa de las partículas elementales. El Bosón de Higgs constituye el cuanto del campo de Higgs, (la más pequeña excitación posible de este campo). Según el modelo propuesto, no posee espín, carga eléctrica o color, es muy inestable y se desintegra rápidamente, su vida media es del orden del zeptosegundo. En algunas variantes del Modelo estándar puede haber varios bosones de Higgs.[2]

La existencia del bosón de Higgs y del campo de Higgs asociado serían el más simple de varios métodos del Modelo estándar de física de partículas que intentan explicar la razón de la existencia de masa en las partículas elementales. Esta teoría sugiere que un campo impregna todo el espacio, y que las partículas elementales que interactúan con él adquieren masa, mientras que las que no interactúan con él, no la tienen. En particular, dicho mecanismo justifica la enorme masa de los bosones vectoriales W y Z, como también la ausencia de masa de los fotones. Tanto las partículas W y Z, como el fotón son bosones sin masa propia, los primeros muestran una enorme masa porque interactúan fuertemente con el campo de Higgs, y el fotón no muestra ninguna masa porque no interactúa en absoluto con el campo de Higgs.

El bosón de Higgs ha sido objeto de una larga búsqueda en física de partículas. Si se demostrara su existencia, el modelo estaría completo. Si se demostrara que no existe, otros modelos propuestos en los que no se involucra el Higgs podrían ser considerados.

El 4 de julio de 2012, el CERN anunció la observación de una nueva partícula «consistente con el bosón de Higgs», pero se necesitaría más tiempo y datos para confirmarlo.[1] El 14 de marzo de 2013 el CERN, con dos veces más datos de los que disponía en el anuncio del descubrimiento en julio de 2012, encontraron que la nueva partícula se ve cada vez más como el bosón de Higgs. La manera en que interactúa con otras partículas y sus propiedades cuánticas, junto con las interacciones medidas con otras partículas, indican fuertemente que es un bosón de Higgs. Todavía permanece la cuestión de si es el bosón de Higgs del Modelo estándar o quizás el más liviano de varios bosones predichos en algunas teorías que van más allá del Modelo estándar.[3]

Introducción general [editar]

En la actualidad, prácticamente todos los fenómenos subatómicos conocidos son explicados mediante el modelo estándar, una teoría ampliamente aceptada sobre las partículas elementales y las fuerzas entre ellas. Sin embargo, en la década de 1960, cuando dicho modelo aún se estaba desarrollando, se observaba una contradicción aparente entre dos fenómenos. Por un lado, la fuerza nuclear débil entre partículas subatómicas podía explicarse mediante leyes similares a las del electromagnetismo (en su versión cuántica). Dichas leyes implican que las partículas que actúen como intermediarias de la interacción, como el fotón en el caso del electromagnetismo y las partículas W y Z en el caso de la fuerza débil, deben ser no masivas. Sin embargo, sobre la base de los datos experimentales, los bosones W y Z, que entonces sólo eran una hipótesis, debían ser masivos.[4]

En 1964, tres grupos de físicos publicaron de manera independiente una solución a este problema, que reconciliaba dichas leyes con la presencia de la masa. Esta solución, denominada posteriormente mecanismo de Higgs, explica la masa como el resultado de la interacción de las partículas con un campo que permea el vacío, denominado campo de Higgs. Peter Higgs fue en solitario uno de los proponentes de dicho mecanismo. En su versión más sencilla, este mecanismo implica que debe existir una nueva partícula asociada con las vibraciones de dicho campo, el bosón de Higgs.

El modelo estándar quedó finalmente constituido haciendo uso de este mecanismo. En particular, todas las partículas masivas que lo forman interaccionan con este campo, y reciben su masa de él. Sin embargo, la existencia del bosón de Higgs es la única parte del mismo que aún necesita ser demostrada.

Hasta la década de 1980 ningún experimento tuvo la energía necesaria para comenzar a buscarlo, dado que la masa que se estimaba que podría tener era demasiado alta (cientos de veces la masa del protón).

El Gran Colisionador de Hadrones (LHC) del CERN en Ginebra, Suiza, inaugurado en 2008, y cuyos experimentos empezaron en 2010, fue construido con el objetivo principal de encontrarlo, probar la existencia del Higgs, y medir sus propiedades, lo que permitiría a los físicos confirmar esta piedra angular de teoría moderna. Anteriormente también se intentó en el LEP (un acelerador previo del CERN) y en el Tevatron (de Fermilab, situado cerca de Chicago en Estados Unidos).

Los físicos de partículas sostienen que la materia está hecha de partículas fundamentales cuyas interacciones están mediadas por partículas de intercambio conocidas como partículas portadoras. A comienzos de la década de 1960 habían sido descubiertas o propuestas un número de estas partículas, junto con las teorías que sugieren cómo se relacionaban entre sí. Sin embargo era conocido que estas teorías estaban incompletas. Una omisión era que no podían explicar los orígenes de la masa como una propiedad de la materia. El teorema de Goldstone, relacionando con la simetría continua dentro de algunas teorías, también parecían descartar muchas soluciones obvias.

El mecanismo de Higgs es un proceso mediante el cual los bosones vectoriales pueden obtener masa invariante sin romper explícitamente invariancia de gauge. La propuesta de ese mecanismo de ruptura espontánea de simetría fue sugerida originalmente en 1962 por Philip Warren Anderson y, en 1964, desarrollada en un modelo relativista completo de forma independiente y casi simultáneamente por tres grupos de físicos: por François Englert y Robert Brout; Las propiedades del modelo fueron adicionalmente consideradas por Guralnik en 1965 y Higgs en 1966. Los papeles mostraron que cuando una teoría de gauge es combinada con un campo adicional que rompe espontáneamente la simetría del grupo, los bosones de gauge pueden adquirir consistentemente una masa finita. En 1967, Steven Weinberg y Abdus Salam fueron los primeros en aplicar el mecanismo de Higgs a la ruptura de la simetría electrodébil y mostraron cómo un mecanismo de Higgs podría ser incorporado en la teoría electrodébil de Sheldon Glashow, en lo que se convirtió en el modelo estándar de física de partículas.

Los tres artículos escritos en 1964 fueron reconocidos como un hito durante la celebración del aniversario 50º de la Physical Review Letters.[5] Sus seis autores también fueron galardonados por su trabajo con el Premio de J. J. Sakurai para física teórica de partículas[6] (el mismo año también surgió una disputa; en el evento de un Premio Nobel, hasta 3 científicos serían elegibles, con 6 autores acreditados por los artículos).[7] Dos de los tres artículos del PRL (por Higgs y GHK) contenían ecuaciones para el hipotético campo que eventualmente se conocería como el campo de Higgs y su hipotético cuanto, el bosón de Higgs. El artículo subsecuente de Higgs, de 1966, mostró el mecanismo de decaimiento del bosón; sólo un bosón masivo puede decaer y las desintegraciones pueden demostrar el mecanismo.

En el artículo de Higgs el bosón es masivo, y en una frase de cierre Higgs escribe que "una característica esencial" de la teoría "es la predicción de multipletes incompletos de bosones escalares y vectoriales". En el artículo de GHK el bosón no tiene masa y está desacoplado de estados masivos. En los exámenes de 2009 y 2011, Guralnik afirma que en el modelo GHK el bosón es sólo en una aproximación de orden más bajo, pero no está sujeta a ninguna restricción y adquiere masa a órdenes superiores y agrega que el artículo de GHK fue el único en mostrar que no hay ningún bosón de Goldstone sin masa en el modelo y en dar un completo análisis del mecanismo general de Higgs.[8] [9]

Además de explicar cómo la masa es adquirida por bosones de vector, el mecanismo de Higgs también predice la relación entre las masas de los bosones W y Z, así como sus acoplamientos entre sí y con el modelo estándar de quarks y leptones. Posteriormente, muchas de estas predicciones han sido verificados por precisas mediciones en los colisionadores LEP y SLC, abrumadoramente confirmando que algún tipo de mecanismo de Higgs tiene lugar en la naturaleza,[10] pero aún no se ha descubierto la manera exacta por la que sucede. Se espera que los resultados de la búsqueda del bosón de Higgs proporcione evidencia acerca de cómo esto es realizado en la naturaleza.

Arrinconando al bosón de Higgs [editar]

Antes del año 2000, los datos recogidos en el Large Electron-Positron collider (LEP) en el CERN para la masa del bosón de Higgs del modelo estándar, habían permitido un límite inferior experimental de 114.4 GeV/c2 con un nivel de confianza del 95% (CL). El mismo experimento ha producido un pequeño número de eventos que podrían interpretarse como resultantes de bosones de Higgs con una masa de alrededor de 115 GeV, justo por encima de este corte, pero el número de eventos fue insuficiente para sacar conclusiones definitivas.[11]

En el Tevatrón del Fermilab, también hubo experimentos en curso buscando el bosón de Higgs. A partir de julio de 2010, los datos combinados de los experimentos del CDF y el DØ en el Tevatron eran suficientes para excluir al bosón de Higgs en el rango de 158 -175 GeV/c2 al 95% de CL.[12] [13] Resultados preliminares a partir de julio de 2011 extendieron la región excluida para el rango de 156-177 GeV/c2 al 95% de CL.[14]

La recopilación de datos y análisis en la busca de Higgs se intensificaron desde el 30 de marzo de 2010, cuando el LHC comenzó a operar en 3,5 TeV.[15] Resultados preliminares de los experimentos ATLAS y CMS del LHC, a partir de julio de 2011, excluyen un bosón de Higgs de modelo estándar en el rango de masa 155-190 GeV/c2[16] y 149-206 GeV/c2,[17] respectivamente, en el 95% CL.

A partir de diciembre de 2011 la búsqueda se había estrechado aproximadamente a la región de 115–130 GeV con un enfoque específico alrededor de 125 GeV, donde tanto el experimento del ATLAS y el CMS informan independientemente un exceso de eventos, [18] [19] lo que significaba que, en este rango de energía, se detectaron, en un número mayor que el esperado, patrones de partículas compatibles con la desintegración de un bosón de Higgs. Los datos eran insuficientes para mostrar si estos excesos fueron debido a fluctuaciones de fondo (es decir, casualidad aleatoria u otras causas), y su significado estadístico no era lo suficientemente grande como para sacar conclusiones o aún ni siquiera para contar formalmente como una "observación", pero el hecho de que dos experimentos independientes habían mostrado excesos alrededor de la misma masa llevó a considerable entusiasmo en la comunidad de la física de partículas.[20]

El 22 de diciembre de 2011, la colaboración de DØ también reportó limitaciones sobre el bosón de Higgs dentro del modelo estándar mínimamente supersimétrico (MSSM), una extensión del modelo estándar. Colisiones protón-antiprotón (pp) con una energía de masa de 1,96 TeV les había permitido establecer un límite superior para la producción del bosón de Higgs dentro de MSSM desde 90 hasta 300 GeV y excluyendo tan β > 20-30 para masas del bosón de Higgs por debajo de 180 GeV (tan β es la relación de los dos valores de la expectativa del vacío del doblete de Higgs).[21]

Por todo esto, a finales de diciembre de 2011, era ampliamente esperado que el LHC podría proporcionar datos suficientes para excluir o confirmar la existencia del bosón de Higgs del modelo estándar para finales de 2012, para cuando su colección de datos de 2012 (en energías de 8 TeV) haya sido examinada.[22]

http://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bos%C3%B3n_de_Higgs

|

|

|

|

|

Astronomical alignment[edit]

Looking east through nave on 23 June 1976, two days after the summer solsticeMary Magdalene's relics in the crypt

In 1976, Hugues Delautre, one of the Franciscan fathers charged with stewardship of the Vézelay sanctuary, discovered that beyond the customary east-west orientation of the structure, the architecture of La Madeleine incorporates the relative positions of the Earth and the Sun into its design. Every June, just before the feast day of Saint John the Baptist, the astronomical dimensions of the church are revealed as the sun reaches its highest point of the year, at local noon on the summer solstice, when the sunlight coming through the southern clerestory windows casts a series of illuminated spots precisely along the longitudinal center of the nave floor.[13][14][15][16][17]

|

|

|

|

|

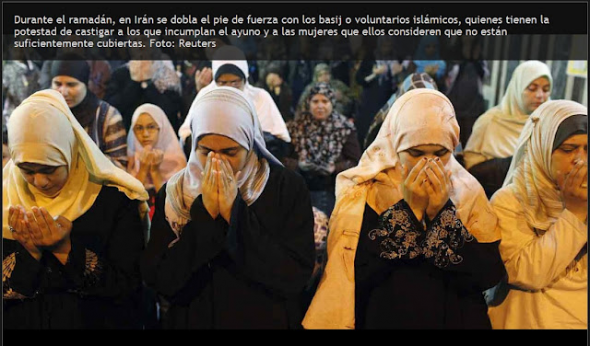

En países como Irán, el Ramadán es impuesto tanto a creyentes como a no creyentes.

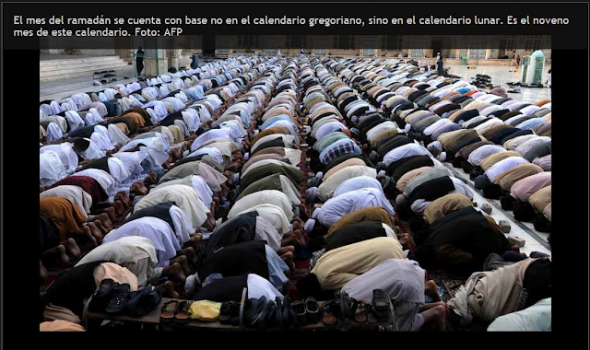

Entre el 20 de julio y el 19 de agosto del 2012 el mundo islámico conmemora el ramadán. Este mes, el noveno en el calendario musulmán, se guarda ayuno desde el amanecer al atardecer. su observancia es uno de los pilares del islam.

Archivos de imagen relacionados

|

|

|

|

|

Different cyclotron size: a) Lawrence ́s first one, b) Venezuela First one (courtesy of Dorly Coehlo), c) Fermi National Laboratory at CERN. And size matters, and Cyclotrons win as best hospital candidates due to Reactors are bigger, harder and difficult to be set in a hospital installation. Can you imagine a nuclear reactor inside a health installation? Radiation Protection Program will consume all the budget available. Size, controlled reactions, electrical control, made cyclotrons easy to install, and baby cyclotrons come selfshielded so hospital don ́t need to spend money in a extremely large bunker. Now on, we are going to talk about our first experience with the set up of a baby cyclotron for medical uses inside the first PET installation in Latin America. “Baby” means its acceleration “D” diameters are suitable to be set inside a standard hospital room dimensions, with all its needs to be safetly shielded for production transmision and synthetized for human uses for imaging in Nuclear Medicine PET routine. When we ask why Cyclotrons are better than reactors for radioisotopes production to be used in Medicine, we also have to have in mind that they has: 1. Less radioactive waste 2. Less harmful debris

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Different-cyclotron-size-a-Lawrence-s-first-one-b-Venezuela-First-one-courtesy-of_fig3_221906035

|

|

|

|

|

Particle of God, The famous Higgs Boson

What is the Higgs boson?

The Higgs boson is a type of elementary particle that is believed to have a fundamental role in the mechanism by which the mass of elementary particles originates. Without mass, the Universe would be a very different place. If the electron had no mass there would be no atoms, which would not exist as we know it, so there would be no chemistry, no biology, and we would not exist. To explain why some particles have mass and others do not, several physicists, among them the British Peter Higgs, postulated in the 60s of the 20th century a mechanism known as the "Higgs field". Just as the photon is the fundamental component of light, the Higgs field requires the existence of a particle that composes it, which physicists call the "Higgs boson". This is the last piece missing to complete the Standard Model of Particle Physics, which describes everything we know about the elementary particles that make up everything we see and how they interact with each other.

Why is the Higgs boson so important?

Because it is the only particle predicted by the Standard Model of Particle Physics that has not yet been discovered. The standard model perfectly describes the elementary particles and their interactions, but an important part remains to be confirmed, precisely the one that responds to the origin of the mass. Without mass, the Universe would be a very different place. If the electron had no mass there would be no atoms, which would not exist as we know it, so there would be no chemistry, no biology, and we would not exist. To explain this, several physicists, including the British Peter Higgs, postulated in the 60s of the twentieth century a mechanism known as the Higgs field. Just as the photon is the fundamental component of the electromagnetic field and light, the Higgs field requires the existence of a particle that composes it, which physicists call the Higgs boson.

History of a search

The search for the Higgs boson began decades ago in particle accelerators such as LEP from CERN or Tevatron from FERMILAB (United States), both already closed. Because the theory does not establish the mass of the Higgs boson, but a wide range of possible values, very powerful accelerators are required to explore this new territory of Physics. The LHC is the culmination of an "energy escalation" aimed at discovering the Higgs boson in the particle accelerators, which has allowed until now to exclude that it has a mass smaller than the equivalent to approximately 115 times that of the proton.

What is a boson?

Subatomic particles are divided into two types: fermions and bosons. Fermions are particles that makeup matter, and bosons carry forces or interactions. The components of the atom (electrons, protons, and neutrons) are fermions, while the photons, the gluons and the W and Z bosons, responsible respectively for electromagnetic nuclear forces, strong and weak nuclear, are bosons.

Wikimedia, Public Domain

How can the Higgs boson be detected?

The Higgs boson can not be detected directly, because once it is produced it disintegrates almost instantaneously giving rise to other more familiar elementary particles. What you can see are your "fingerprints", those other particles that can be detected in the LHC. Within the accelerator ring, the protons collide with each other at a speed close to that of light. When collisions occur at strategic points where large detectors are located, the energy of the movement is released and is available to generate other particles. The greater the energy of the particles that collide, the more mass that will result, according to the famous Einstein E2 equation.

The Higgs boson points the way to the New Physics

New results obtained at the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) have shown how the Higgs boson, the heaviest known elementary particle, interacts not only with massive particles but also with particles devoid of mass. It was observed due to the disintegration of the Higgs boson in two photons, which are massless particles. According to quantum mechanics, the Higgs boson can fluctuate for a brief moment in a top quark and a top antiquark, which cancel each other rapidly forming a pair of photons. The top quark is an elementary particle that belongs to the third generation of quarks, the only elementary particles that interact with the four fundamental forces: nuclear, electromagnetic, weak and gravity. Quarks not only form nuclear matter but also sometimes subatomic particles such as protons and neutrons. Quarks exist with their corresponding antiparticles. The top quark is the most massive of the quarks discovered to date. It is a very unstable particle, so it does not have time to merge with other quarks and form new particles known as hadrons. Its antiparticle is the top antiquark. The Higgs boson or Higgs particle is an elementary particle proposed in the standard model of particle physics. It has no spin, electric charge or color, is very unstable and disintegrates quickly: its half-life is of the order of one billionth of a second (zeptosecond).

Wikimedia, Public Domain

References

|

|

|

|

|

Pierre Charles L'Enfant

This article is about the person who designed the basic plan for Washington, D.C. (capital city of the U.S.). For his father, see Pierre L'Enfant (painter). Pierre "Peter" Charles L'Enfant (French: [pjɛʁ ʃɑʁl lɑ̃fɑ̃]; August 2, 1754 – June 14, 1825) was a French-American artist, professor, and military engineer. In 1791, L'Enfant designed the baroque-styled plan for the development of Washington, D.C., after it was designated to become the capital of the United States following its relocation from Philadelphia. His work, known as the L'Enfant Plan,[1] inspired plans for other major world capitals, including Brasília, New Delhi, and Canberra. In the U.S., plans for the development of three major cities, Detroit, Indianapolis, and Sacramento, were inspired from from L'Enfant's plan for Washington, D.C.[A] [3]

Early life and education

[edit]

L'Enfant was born on August 2, 1754, in the Gobelins section of Paris, France, in the 13th arrondissement on the city's left bank.[4] He was the third child and second son of Pierre L'Enfant (1704–1787), a painter and professor at Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture known for his panoramas of battles,[5] and Marie Charlotte Leullier, the daughter of a French military officer. In 1758, his brother Pierre Joseph died at six, and Pierre Charles became the eldest son.[6] He studied with an intense curriculum at the Royal Academy from 1771 until 1776 with his father being one of his instructors. Academy classes were held at the Louvre, benefiting from the close proximity to some of Paris' greatest landmarks, such as the Tuileries Garden and Champs-Élysées, both designed by André Le Nôtre, and Place de la Concorde. L'Enfant would have also learned about city and urban planning during his time at the academy, likely examining baroque plans for Rome by Domenico Fontana and London by Sir Christopher Wren.

He was described by William Wilson Corcoran as "a tall, erect man, fully six feet in height, finely proportioned, nose prominent, of military bearing, courtly air and polite manners, his figure usually enveloped in a long overcoat and surmounted by a bell-crowned hat -- a man who would attract attention in any assembly."[7] Sarah De Hart, daughter of New Jersey statesman John De Hart, drew a silhouette of L'Enfant in 1785, which now hangs in the Diplomatic Reception Rooms at the United States Department of State.

Boulevard Saint Marcel in Paris, where L'Enfant grew up

After his education L'Enfant was recruited by Pierre Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais to serve in the American Revolutionary War in the United States. He arrived in 1777 at the age of 23, and served as a military engineer in the Continental Army with Major General Lafayette.[8] He was commissioned as a captain in the Corps of Engineers on April 3, 1779, to rank from February 18, 1778.[9]

Despite his aristocratic origins, L'Enfant closely identified with the United States, changing his first name from Pierre to Peter when he first came to the rebelling colonies in 1777.[10][11][12] L'Enfant served on General George Washington's staff at Valley Forge. While there, the Marquis de Lafayette commissioned L'Enfant to paint a portrait of Washington.[13]

During the war, L'Enfant made a number of pencil portraits of George Washington and other Continental Army officers.[14] He also made at least two paintings of Continental Army encampments in 1782.[15] They depict panoramas of West Point and Washington's tent at Verplanck's Point. The latter details what is believed to be "the only known wartime depiction of Washington’s tent by an eyewitness."[16] The seven-and-a-half-foot-long painting was purchased by the Museum of American Revolution in Philadelphia.

In the fall of 1779, L’Enfant contributed to the Regulations for the Order and Discipline of the Troops of the United States, authored by General Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben. He was tasked to draft the eight "plates" or illustrations detailing camp and troop formations, as he was the only artistically trained individual involved. The "Blue Book" was completed by April 1779, receiving approval from General Washington and Congress. For his efforts, Congress awarded L’Enfant $500 and officially promoted him to captain of engineers, retroactive to February 1778.

L'Enfant was wounded at the Siege of Savannah on October 9, 1779. He recovered and became a prisoner of war at the surrender of Charleston, South Carolina, on May 12, 1780. He was exchanged in November 1780 and served on General Washington's staff for the remainder of the American Revolution. While the historical consensus generally attributes the creation of the Badge of Military Merit, later known as the Purple Heart, to George Washington in 1782, there is an implied claim by Pamela Scott, Washington D.C. historian and former editor of The L'Enfant Papers at the Library of Congress, that L'Enfant may have conceived the medal's design. L'Enfant was promoted by brevet to Major in the Corps of Engineers on May 2, 1783, in recognition of his service to the cause of American liberty. He was discharged when the Continental Army was disbanded in December 1783.[17] In acknowledgment of his Revolutionary War contributions, L'Enfant received 300 acres of land in present-day Ohio from the United States. However, he never set foot on or resided in the granted land. A map outlining the territory was sketched on the reverse side of a segment of L'Enfant's land deed, signed by President Thomas Jefferson on January 13, 1803.[18]

Post–Revolutionary War

[edit]

Alexander Hamilton Alexander Hamilton, who supported L'Enfant and helped him secure work in Paterson, New Jersey after he was dismissed from the federal city project

Following the American Revolutionary War, L'Enfant settled in New York City and achieved fame as an architect by redesigning the City Hall in New York for the First Congress of the United States (See: Federal Hall).[19]

L'Enfant also designed furniture and houses for the wealthy, as well as coins and medals. Among the medals was the eagle-shaped badge of the Society of the Cincinnati, an organization of former officers of the Continental Army of which he was a founder. At the request of George Washington, the first President of the Society, L'Enfant had the insignias made in France during a 1783–84 visit to his father and helped to organize a chapter of the Society there.[20]

In 1787, L'Enfant received an inheritance upon his father's death that included a farm in Normandy[citation needed]. His military pension and success as a designer provided financial stability enabling him to pursue his career and contribute to various projects for a period of time. While L'Enfant was in New York City, he was initiated into Freemasonry. His initiation took place on April 17, 1789, at Holland Lodge No. 8, F & A M, which the Grand Lodge of New York F & A M had chartered in 1787. L'Enfant took only the first of three degrees offered by the Lodge and did not progress further in Freemasonry.[21]

L'Enfant designed the "Glory" ornamentation above the altar in St. Paul's Church. The chapel, built in 1766, is the oldest continuously used building in New York City. George Washington worshipped there on his inauguration day. The intricate design vividly depicts Mt. Sinai amidst clouds and lightning, capturing the dramatic moment of divine revelation. At the center of the piece is the Hebrew word for "God" enclosed within a triangle, symbolizing the Holy Trinity. Below, the two tablets of the Law are inscribed with the Ten Commandments, highlighting the enduring significance of these foundational moral laws.

L'Enfant was also a close friend of Alexander Hamilton. Some of their correspondences from 1793 to 1801 now reside in the Library of Congress.[22] Hamilton is credited with helping L'Enfant with the federal city commission.

|

|

|

Primeira Primeira

Anterior

206 a 220 de 220

Seguinte Anterior

206 a 220 de 220

Seguinte

Última

Última

|