|

|

Eratóstenes

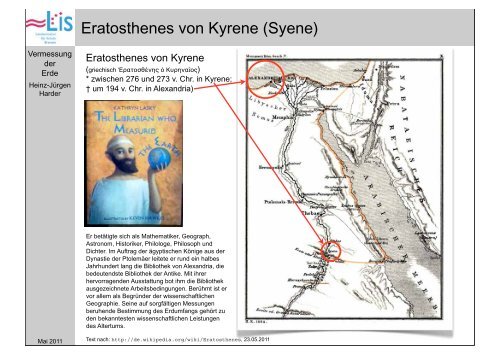

Eratóstenes de Cirene (en griego antiguo Ἐρατοσθένης, Eratosthénēs) (Cirene, 276 a. C.1-Alejandría, 194 a. C.) fue un matemático, astrónomo y geógrafo griego de origen cirenaico.

Eratóstenes era hijo de Aglaos. Estudió en Alejandría y durante algún tiempo en Atenas. Fue discípulo de Aristón de Quíos, de Lisanias de Cirene y del poeta Calímaco y también gran amigo de Arquímedes. En el año 236 a. C., Ptolomeo III le llamó para que se hiciera cargo de la Biblioteca de Alejandría, puesto que ocupó hasta el fin de sus días. La Suda afirma que, tras perder la vista, se dejó morir de hambre a la edad de 80 años; sin embargo, Luciano dice que llegó a la edad de 82 años; también Censorinosostiene que falleció cuando tenía 82 años.

Esfera armilar[editar]

A Eratóstenes se le atribuye la invención, hacia 255 a. C., de la esfera armilar que aún se empleaba en el siglo XVII. Aunque debió de usar este instrumento para diversas observaciones astronómicas, sólo queda constancia de la que le condujo a la determinación de la oblicuidad de la eclíptica. Determinó que el intervalo entre los trópicos (el doble de la oblicuidad de la eclíptica) equivalía a los 11/83 de la circunferencia terrestre completa, resultando para dicha oblicuidad 23º 51' 19", cifra que posteriormente adoptaría el astrónomo Claudio Ptolomeo.

Según algunos historiadores, Eratóstenes obtuvo un valor de 24º y el refinamiento del resultado se debió hasta 11/83 al propio Ptolomeo. Además, según Plutarco, de sus observaciones astronómicas durante los eclipses dedujo que la distancia al Sol era de 804 000 000 estadios, la distancia a la Luna 780 000 estadios y, según Macrobio, que el diámetro del Sol era 27 veces mayor que el de la Tierra. Realmente el diámetro del Sol es 109 veces el de la Tierra y la distancia a la Luna es casi tres veces la calculada por Eratóstenes, pero el cálculo de la distancia al Sol, admitiendo que el estadio empleado fuera de 185 metros, fue de 148 752 060 km, muy similar a la unidad astronómica actual. A pesar de que se le atribuye frecuentemente la obra Katasterismoi, que contiene la nomenclatura de 44 constelaciones y 675 estrellas, los críticos niegan que fuera escrita por él, por lo que se suele designar Pseudo-Eratóstenes a su autor.

Medición de las dimensiones de la Tierra[editar]

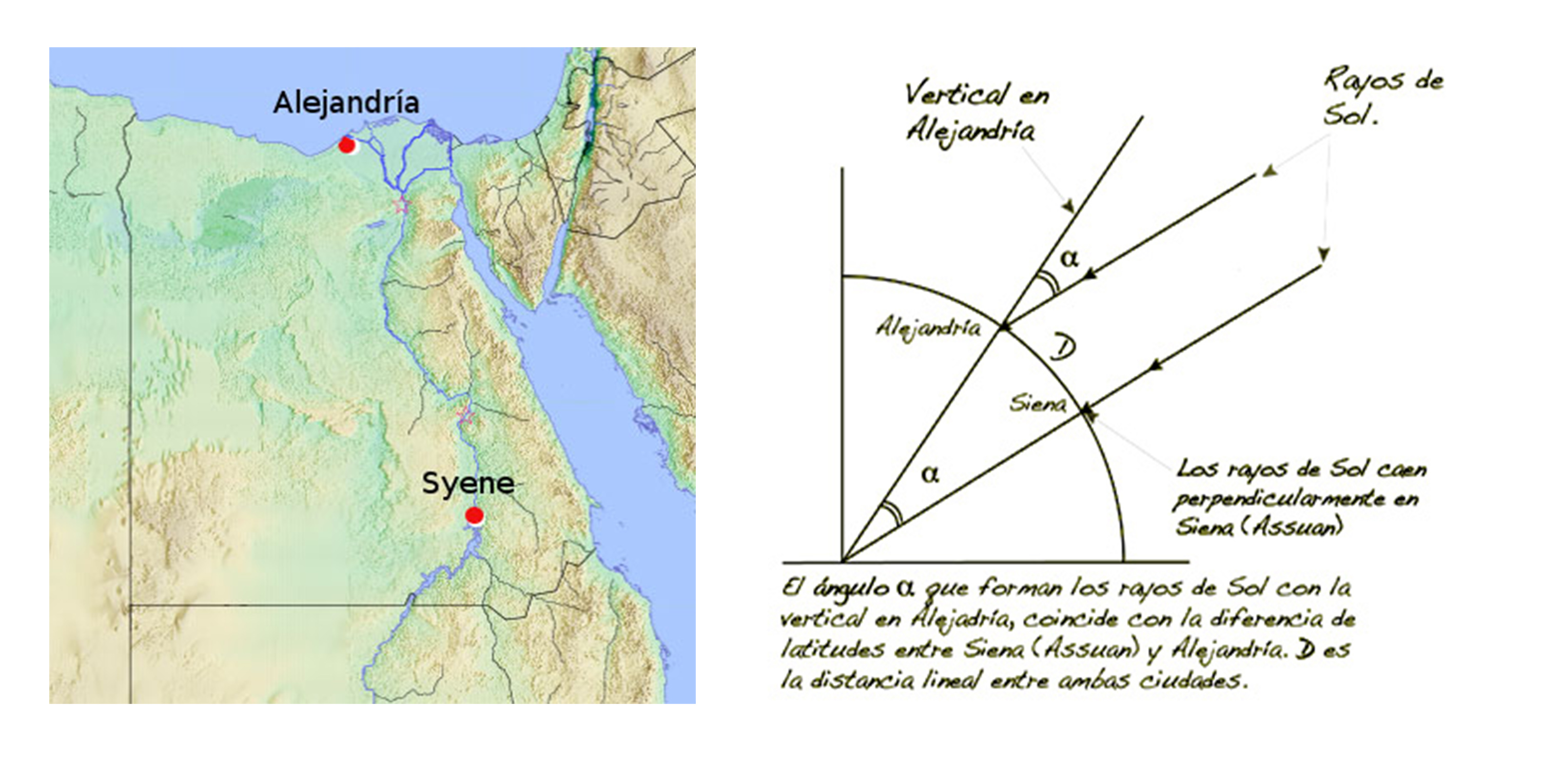

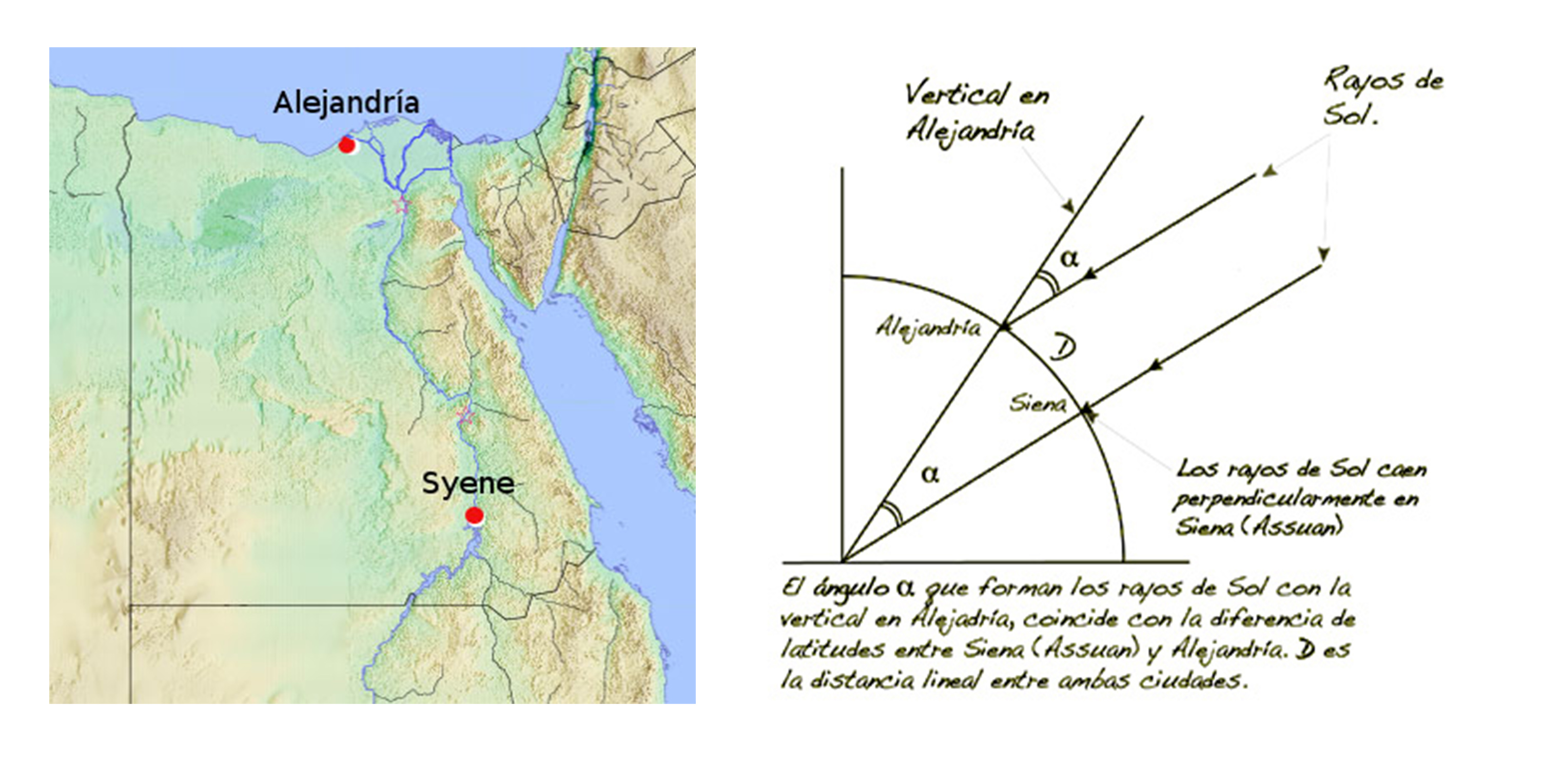

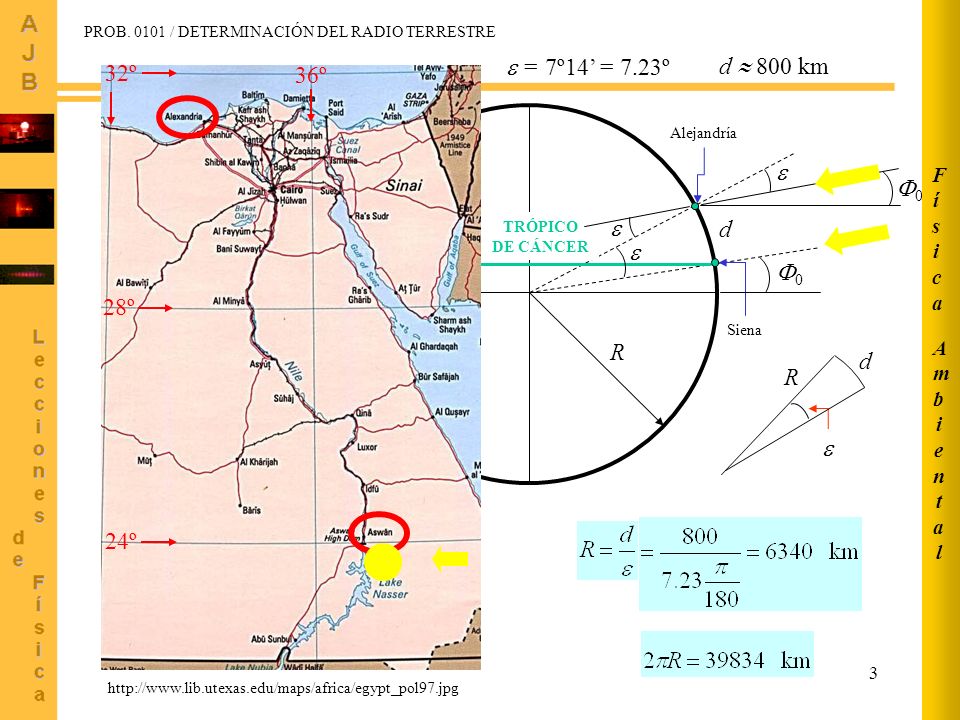

En el solsticio de verano, los rayos solares inciden perpendicularmente sobre Siena ( Asuán). En Alejandría, más al norte, midiendo la altura de un edificio y la longitud de la sombra que proyecta, se puede determinar el ángulo formado con el plano de la eclíptica, en el que se encuentran el Sol y la ciudad de Siena, ángulo que es precisamente la diferencia de latitud entre ambas ciudades. Conocida ésta, basta medir el arco de circunferencia y extrapolar el resultado a la circunferencia completa (360º).

Reconstrucción del siglo XIX (según Bunbury) del mapa de Eratóstenes del mundo conocido en su época.

Sin embargo, el principal motivo de su celebridad es sin duda la determinación del tamaño de la Tierra. Para ello inventó y empleó un método trigonométrico, además de las nociones de latitud y longitud, al parecer ya introducidas por Dicearco, por lo que bien merece el título de padre de la geodesia.

Por referencias obtenidas de un papiro de su biblioteca, sabía que en Siena (hoy Asuán, Egipto) el día del solsticio de verano los objetos verticales no proyectaban sombra alguna y la luz alumbraba el fondo de los pozos; esto significaba que la ciudad estaba situada justamente sobre la línea del trópico y su latitud era igual a la de la eclíptica que ya conocía. Eratóstenes, suponiendo que Siena y Alejandría tenían la misma longitud (realmente distan 3º) y que el Sol se encontraba tan alejado de la Tierra que sus rayos podían suponerse paralelos, midió la sombra en Alejandría el mismo día del solsticio de verano al mediodía, demostrando que el cenit de la ciudad distaba 1/50 parte de la circunferencia, es decir, 7º 12' del de Alejandría. Según Cleomedes, Eratóstenes se sirvió del scaphium o gnomon (un protocuadrante solar) para el cálculo de dicha cantidad.

Posteriormente, tomó la distancia estimada por las caravanas que comerciaban entre ambas ciudades, aunque bien pudo obtener el dato en la propia Biblioteca de Alejandría, fijándola en 5000 estadios, de donde dedujo que la circunferencia de la Tierra era de 250 000 estadios, resultado que posteriormente elevó hasta 252 000 estadios, de modo que a cada grado correspondieran 700 estadios. También se afirma que Eratóstenes, para calcular la distancia entre las dos ciudades, se valió de un regimiento de soldados que diera pasos de tamaño uniforme y los contara.

Admitiendo que Eratóstenes usase el estadio ático-italiano de 184.8 m, que era el que solía utilizarse por los griegos de Alejandría en aquella época, el error cometido sería de 6.192 kilómetros (un 15 %). Sin embargo, hay quien defiende que empleó el estadio egipcio (300 codos de 52,4 cm), en cuyo caso la circunferencia polar calculada hubiera sido de 39614 km, frente a los 40008 km considerados en la actualidad, es decir, un error de menos del 1%.

Ahora bien, es imposible que Eratóstenes diera con la medida exacta de la circunferencia de la Tierra debido a errores en los supuestos que calculó. Tuvo que haber tenido un margen de error considerable y por lo tanto no pudo haber usado el estadio egipcio:2

- Supuso que la Tierra es perfectamente esférica, lo que no es cierto. Un grado de latitud no representa exactamente la misma distancia en todas las latitudes, sino que varía ligeramente de 110,57 km en el Ecuador hasta 111,7 km en los Polos. Por eso no podemos suponer que 7º entre Alejandría y Siena representen la misma distancia que 7º en cualquier otro lugar a lo largo de todo el meridiano.

- Supuso que Siena y Alejandría se encontraban situadas sobre un mismo meridiano, lo cual no es así, ya que hay una diferencia de 3 grados de longitud entre ambas ciudades.

- La distancia real entre Alejandría y Siena (hoy Asuán) no es de 924 km (5000 estadios ático-italiano de 184,8 m por estadio), sino de 843 km (distancia aérea y entre los centros de las dos ciudades), lo que representa una diferencia de 81 km.

- Realmente Siena no está ubicada exactamente sobre el paralelo del trópico de cáncer (los puntos donde los rayos del sol caen verticalmente a la tierra en el solsticio de verano). Actualmente se encuentra situada a 72 km (desde el centro de la ciudad). Pero debido a que las variaciones del eje de la Tierra fluctúan entre 22,1 y 24,5º en un período de 41000 años, hace 2000 años se encontraba a 41 km.

- La medida de la sombra que se proyectó sobre la vara de Eratóstenes hace 2.200 años debió ser de 7,5º o 1/48 parte de una circunferencia y no 7,2º o 1/50 parte. Puesto que en aquella época no existía el cálculo trigonométrico, para calcular el ángulo de la sombra, Eratóstenes pudo haberse valido de un compás,3 para medir directamente dicho ángulo, lo que no permite una medida tan precisa.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Erat%C3%B3stenes

|

|

|

|

|

Subestación eléctrica de maniobras Magdalena I (Parque Solar Magdalena I)

NOVIEMBRE 17, 2021 PV MAGAZINE

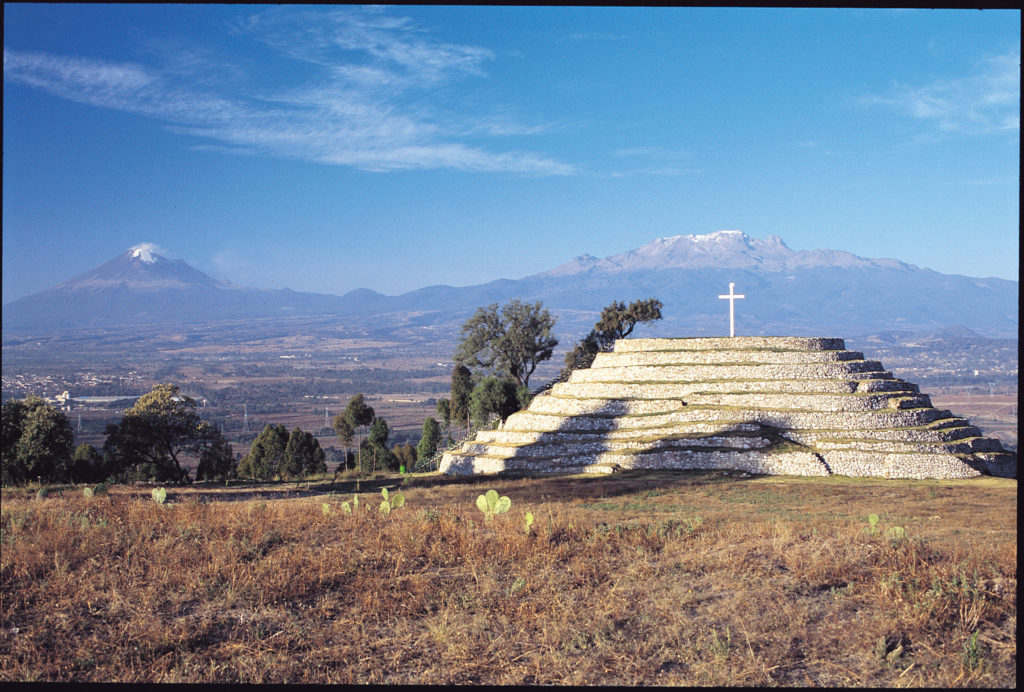

Pirámide de la Espiral Xochitecatl, Tlaxcala

Fotografía: Gobierno del estado de Tlaxcala

La Dirección General de Impacto y Riesgo Ambiental de la Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales informa que ha recibido la documentación de la firma promovente Más Energía, para el proyecto de la Subestación eléctrica de maniobras Magdalena I (Parque Solar Magdalena I).

El proyecto consiste en la construcción, operación y mantenimiento de una subestación eléctrica de maniobras, dos accesos, y una línea eléctrica de entronque de 400 Kv que se interconectará a una línea de transmisión eléctrica existente de 400 Kv propiedad de la Comisión Federal de Electricidad para desahogar la energía eléctrica que se genera en la planta fotovoltaica parque solar Magdalena I al Sistema Eléctrico Nacional.

Este contenido está protegido por derechos de autor y no se puede reutilizar. Si desea cooperar con nosotros y desea reutilizar parte de nuestro contenido, contacte: editors@pv-magazine.com.

6 Schematic representation of a cyclotron. The distance between the pole pieces of the magnet is shown larger than reality to allow seeing what is inside

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-representation-of-a-cyclotron-The-distance-between-the-pole-pieces-of-the_fig3_237993541

|

|

|

|

|

ANCIENT EGYPTIAN GEODESY - PART II

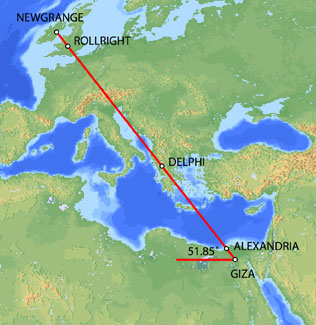

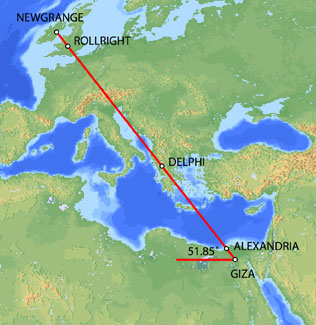

The great circle alignment from Giza to Alexandria has an azimuth of 51.85° north of due west from Giza (the same angle as the slope of the Great Pyramid). Extended beyond Alexandria, this great circle also crosses over Delphi, Rollright and Newgrange, as well as the city of London.

Map image © VectorGlobe

The azimuth of a great circle alignment from Dendera to Paris is also 51.85° north of due west.

Map image - Roger Hedin

Dendera was dedicated to Isis/Sirius. The ancient Egyptian year began on the date of the heliacal rising of Sirius in mid July. The helical rising of Sirius heralded the annual inundation of the Nile that was essential to the welfare of ancient Egypt. The axis of the temple of Isis at Dendera was aligned 20° south of due east, pointing directly at the rising point of Sirius from the latitude of Dendera.

Robert Bauval describes a number of connections between Isis/Sirius and Paris in Talisman (2004). Isis is shown riding on a boat in many ancient Egyptian drawings and carvings. At the direction of Napoleon, Sirius and a statue of Isis were added to the coat of arms for Paris shown below.

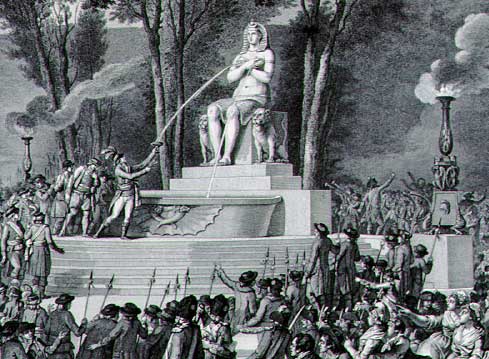

During the French revolution, a statue of Isis known as the Fountain of Regeneration was constructed on the former site of the Bastille. The engraving below commemorated this statue.

Fountain of Regeneration Engraving

The Elysian Fields is described as a place of eternal salvation in the ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead. Named after the Elysian Fields, the Champs Elysees is the main axis of Paris. The names Elysian and Elysees both suggest an association with Isis. The photograph below is facing southeast. The Arc de Triumphe is visible in the background. Beyond the Arc de Triumphe is the Louvre. The azimuth of the Champs Elysees is 26° south of due east, pointing directly at the rising point of Sirius/Isis from the latitude of Paris.

The termination point of the Champs Elysees to the northwest is the Grande Arche, in the foreground of the picture above. The axis of the Grande Arche is offset 6.33° south of the axis of the Champs Elysees. With an azimuth of just over 32° south of due east, the azimuth of the axis of the Grande Arche is the same as the azimuth of the great circle alignment from Paris to Dendera.

The Grande Arche is a nearly perfect cube with a height of 110 meters, a width of 108 meters and a depth of 112 meters. It is often described as a cube with side lengths of 110 meters. This is equal to 210 ancient Egyptian cubits:

110/210 = .5238

.5238 meters is a precise measure of the ancient Egyptian cubit, equating to 20.6222 inches, well within the ± .005 inches in Petrie's 20.62 inch measure of the ancient Egyptian cubit. Instead of the usual comparisons between the cubit and the meter of .52375/1 or .524/1, the best comparative measure may be the simple fraction of 11/21 that is suggested by the Grande Arche.

Image © Insecula.com

The sides of the Grande Arche are divided into 5 x 5 large panels and within each large panel are 7 x 7 smaller panels. Side lengths of 110 meters suggest lengths of 22 meters for the sides of the large panels with lengths of 22/7 meters for the sides of the smaller panels. The fraction 22/7 equals 3.1428, an accurate expression of π that is also found in the dimensions of the Great Pyramid. Side lengths of 210 cubits in the Grande Arche suggest lengths of 42 cubits for the sides of the large panels and 6 cubits for the sides of the smaller panels. This also shows that the relationship between the meter and the cubit is 6/π, using the measure of 22/7 for π:

21/11 = 6/π

22/7 x 21/11 = 6

The northern pyramid at Dashur, known as the Red Pyramid, was the first true (smooth sided) pyramid built in Egypt and it was the last pyramid built prior to construction of the Great Pyramid. The baselengths of the Red Pyramid are 420 cubits (220 meters) long, 20x multiples of 21/11.

Image by Jon Bodsworth

One of the oldest stone circles in England is at Rollright. The diameter of the Rollright circle is 31.4 meters, an accurate expression of π times 10 meters. Given the 6/π relationship between the meter and the cubit, the diameter of the Rollright circle is also 60 ancient Egyptian cubits.

BACK

|

|

|

|

|

New International VersionMeanwhile a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was a learned man, with a thorough knowledge of the Scriptures.

New Living TranslationMeanwhile, a Jew named Apollos, an eloquent speaker who knew the Scriptures well, had arrived in Ephesus from Alexandria in Egypt.

English Standard VersionNow a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, competent in the Scriptures.

Berean Standard BibleMeanwhile a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, well versed in the Scriptures.

Berean Literal BibleNow a certain Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus, being an eloquent man, mighty in the Scriptures.

King James BibleAnd a certain Jew named Apollos, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man, and mighty in the scriptures, came to Ephesus.

New King James VersionNow a certain Jew named Apollos, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man and mighty in the Scriptures, came to Ephesus.

New American Standard BibleNow a Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus; and he was proficient in the Scriptures.

NASB 1995Now a Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus; and he was mighty in the Scriptures.

NASB 1977Now a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus; and he was mighty in the Scriptures.

Legacy Standard BibleNow a Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, arrived at Ephesus; and he was mighty in the Scriptures.

Amplified BibleNow a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent and cultured man, and well versed in the [Hebrew] Scriptures.

Christian Standard BibleNow a Jew named Apollos, a native Alexandrian, an eloquent man who was competent in the use of the Scriptures, arrived in Ephesus.

Holman Christian Standard BibleA Jew named Apollos, a native Alexandrian, an eloquent man who was powerful in the use of the Scriptures, arrived in Ephesus.

American Standard VersionNow a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by race, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus; and he was mighty in the scriptures.

Contemporary English VersionA Jewish man named Apollos came to Ephesus. Apollos had been born in the city of Alexandria. He was a very good speaker and knew a lot about the Scriptures.

English Revised VersionNow a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by race, a learned man, came to Ephesus; and he was mighty in the scriptures.

GOD'S WORD® TranslationA Jew named Apollos, who had been born in Alexandria, arrived in the city of Ephesus. He was an eloquent speaker and knew how to use the Scriptures in a powerful way.

Good News TranslationAt that time a Jew named Apollos, who had been born in Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent speaker and had a thorough knowledge of the Scriptures.

International Standard VersionMeanwhile, a Jew named Apollos arrived in Ephesus. He was a native of Alexandria, an eloquent man, and well versed in the Scriptures.

Majority Standard BibleMeanwhile a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus. He was an eloquent man, well versed in the Scriptures.

NET BibleNow a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, arrived in Ephesus. He was an eloquent speaker, well-versed in the scriptures.

New Heart English BibleNow a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by race, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus. He was mighty in the Scriptures.

Webster's Bible TranslationAnd a certain Jew named Apollos, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man, and mighty in the scriptures, came to Ephesus.

Weymouth New TestamentMeanwhile a Jew named Apollos came to Ephesus. He was a native of Alexandria, a man of great learning and well versed in the Scriptures.

World English BibleNow a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by race, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus. He was mighty in the Scriptures.

Literal Translations

Literal Standard VersionAnd a certain Jew, Apollos by name, an Alexandrian by birth, a man of eloquence, being mighty in the Writings, came to Ephesus;

Berean Literal BibleNow a certain Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, came to Ephesus, being an eloquent man, mighty in the Scriptures.

Young's Literal TranslationAnd a certain Jew, Apollos by name, an Alexandrian by birth, a man of eloquence, being mighty in the Writings, came to Ephesus,

Smith's Literal TranslationAnd a certain Jew, Apollos by name, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, arrived at Ephesus, being able in the writings.

Catholic Translations

Douay-Rheims BibleNow a certain Jew, named Apollo, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man, came to Ephesus, one mighty in the scriptures.

Catholic Public Domain VersionNow a certain Jew named Apollo, born at Alexandria, an eloquent man who was powerful with the Scriptures, arrived at Ephesus.

New American BibleA Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria, an eloquent speaker, arrived in Ephesus. He was an authority on the scriptures.

New Revised Standard VersionNow there came to Ephesus a Jew named Apollos, a native of Alexandria. He was an eloquent man, well-versed in the scriptures.

Translations from Aramaic

Lamsa BibleAnd a certain Jew named A-pol’los, a native of Al-ex-an’dri-a, an eloquent man and well versed in the scriptures, came to Eph'esus.

Aramaic Bible in Plain EnglishOne man, a Jew whose name was Apollo, a native of Alexandria and instructed in the word, was familiar with the Scriptures and he came to Ephesaus.

NT Translations

Anderson New TestamentAnd a certain Jew, named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, and mighty in the Scriptures, came to Ephesus.

Godbey New TestamentAnd a certain Jew, Apollos by name, an Alexandrian by race, an eloquent man, came into Ephesus, being mighty in the scriptures.

Haweis New TestamentNow a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, a man of eloquence, who was powerful in the Scriptures, had come to Ephesus.

Mace New TestamentIn the mean time a Jew, nam'd Apollos, born at Alexandria, a man of letters, and vers'd in the scriptures, arriv'd at Ephesus.

Weymouth New TestamentMeanwhile a Jew named Apollos came to Ephesus. He was a native of Alexandria, a man of great learning and well versed in the Scriptures.

Worrell New TestamentNow a certain Jew, Apollos by name, an Alexandrian by birth, a learned man, came down to Ephesus; and he was mighty in the Scriptures.

Worsley New TestamentNow there came to Ephesus a certain Jew named Apollos, an Alexandrian by birth, an eloquent man, and mighty in the scriptures.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primer Primer  Anterior 2 a 3 de 3 Siguiente Anterior 2 a 3 de 3 Siguiente  Último Último  |

|

|

|

|

|

Metric Time

Aside from you chronically late people, we all know how time works:

This system is okay. But also, it’s kind of crazy.

Why 60 minutes per hour? Why 60 seconds per minute? It goes back to Babylon, with their base 60 number system—the same heritage that gives us 360 degrees in a circle. Now, that’s all well and good for Babylon 5 fans, but our society isn’t base-60. It’s base-10. Shouldn’t our system of measuring time reflect that?

So ring the bells, beat the drums, and summon the presidential candidates to “weigh in,” because I hereby give you… metric time.

Now, this represents a bit of a change. The new seconds are a bit shorter. The new minutes are a bit longer. And the new hours are quite different—nearly two and a half times as long.

So why do this? Because it’d be so much easier to talk about time!

Here’s one improvement: analog clocks are easier to read. At first glance, the improvement may not be so obvious—we’ve simply reshuffled the numbers a bit.

But notice, the minute hand makes more sense now. When it’s at the 2, we’re 20 minutes past the hour. When it’s at the 7, we’re 70 minutes after the hour. And so on.

Second, times are no longer duplicated. For example, instead of needing to distinguish between 6am and 6pm, we can simply say “2:50” and “7:50.” (This is, of course, how “military time” currently works.)

Third—this is a big one—the time tells you how far through the day you are. The time 2:00 is exactly 20% of the way through the day. At 8:76, we’re exactly 87.6% of the way through the day.

Fourth, consider the moment when we’re 99.9% of the way through the day. In the new metric system, we get to watch the clock roll from 9:99 back around to 0:00. Isn’t that nicer and more conclusive than 11:59pm rolling around to 12:00am?

Fifth, it’s so much easier to talk about longer times. Two and a half days? That’s 25 hours. Three days and 6 hours? That’s simply 3.6 days. Since an hour is now a nice decimal fraction of a day, these conversions become easy.

Will there be adjustments to make? Certainly! But the adjustments are half of the fun.

Let’s start, as all good things do, with television. Whether you enjoy half-hour sitcoms or hour-long dramas, the length of your favorite shows is probably going to change. Why? Because, under our new system, what we now call “half an hour” will be 20.83 minutes. What we now call “an hour” will be 41.67.

There’s nothing magical about these “half-hour” and “hour” lengths, obviously. They were chosen simply because they were nice round numbers. But under the new system, they aren’t! Since it’d be silly to divide the TV schedule into 21-minute intervals, presumably television networks would tweak the lengths to go more evenly into an hour.

If so, they’d have two choices: 5 blocks per hour (i.e., two dramas, plus a sitcom), or 4 blocks per hour (i.e., two dramas).

If you choose the former, shows will be 4% shorter than today, leading to accelerated storytelling. (It’s the same change that’s unfolded over the last 20 years, as increased ad time has squeezed the shows themselves to be shorter.)

And if you choose the latter, shows will be 20% longer. They’ll perhaps unfold at a slower, more cinematic speed. Either way, expect the pacing and rhythm of TV shows to change.

Sports run into the same issue. Football will probably opt for four quarters of 10 minutes each, which shortens the game by 4%. Expect slightly diminished scoring as a result. (And, if we’re lucky, diminished concussions.)

Hockey, meanwhile, might go for three periods of 15 minutes each, which actually makes the game 8% longer. It might give someone a chance to tackle Wayne Gretzky’s scoring records (but then again, probably not—he’s way out of reach right now).

I’d expect soccer to select two halves of 30 minutes each, which (as with American football) shortens games by 4%. If you thought soccer was too high-scoring already, you’re in luck (and also in a very small minority, I suspect).

When it comes to sports, the lengths of games won’t be the only thing changing. We also need to reconsider record running times.

Usain Bolt’s world-record for the 100-meter dash (currently 9.58 seconds) would be, under the new system, 11.09 metric seconds. Doing the 100m in 11 metric seconds might be achievable in the future, but 10 seconds? Perhaps never. (That’s the equivalent of 8.64 of our seconds!)

What about the mile? Well, it’s a little funny to imagine a world with metric time still worrying about that strange unit of distance (5280 feet? Really?), but the famed 4-minute mile would correspond to a 2.78-minute mile.

This is weird because, for top runners in the 1940s and 1950s, the barrier to running a 4-minute mile may have been less physiological than psychological. Would the 2.8-minute mile have felt as intimidating? Would the 3-minute mile? Perhaps it’d be the 2.5-minute mile, seeing as the current world record (3:43 in our old system) is 2.58 metric minutes?

And we might as well mention the marathon, where the world record time (currently 2:02:57) is now under an hour: 85 minutes, 38 seconds. I suspect that the 1-hour marathon would be a real badge of honor, something that every distance runner aspires to.

Leaving sports aside, what about food?

Restaurants would open for breakfast at perhaps 3:00 or 3:50. (Of course, coffee shops like Starbucks might open as early as 2:50.)

You’d get lunch around 5:00—that is to say, noon. Under our current system, I feel silly eating before 11:30, which is 4:80 under the new system. But I wonder—would I feel comfortable grabbing lunch at 4:75? Perhaps even 4:60 (even though that’s earlier than 11am under our current scheme)?

Eating is psychological, and how we number our hours might steer our behavior.

As for dinner, I suspect 7:50 to 8:00 would be the preferred time (although the famously late-eating Spaniards might hold off until 8:75 or 9:00).

Other numbers change, too. Take speed limits: the typical 65mph limit on many highways translates to 156 mph under the new system; I suspect we’d see that bumped up to 160 mph or down to 150 mph for the sake of roundness (which translates to 66.7mph or 62.5mph under our current system).

The speed of sound? Not 340 meters per second any longer; it’s now just 294 meters per second. Meters haven’t changed, of course, but seconds have gotten shorter!

And the speed of light? Unfortunately, we lose the lovely number 300 million meters per second; instead, it becomes roughly 260 million meters per second.

Speaking of light, on the equinox, you get 5 hours of light and 5 hours of dark.

The winter solstice is pretty grim: in London, you’d see just 3 hours, 25 minutes, and 25 seconds of daylight.

The summer solstice is nice, though: London would get 6 hours, 93 minutes of sun.

Okay, time to come clean: I propose this without a single iota of seriousness. It’d be insane to ditch our current system. We’re used to it. We’ve agreed upon it. We’ve built our lives around it. The hassle of a change far outweighs the gains.

But I still love the thought experiment. It asks you, in some small way, to reimagine your life. How do you spend your time? How do you measure the success of a day? When you plan your hours, are you conceding to the arbitrary dictates of a quirky clock, or are you truly giving your tasks the time that they deserve? If I scrambled your sense of time, relabeling all your moments, would it change the way you feel about them? Do the numbers we assign to times matter? Or are we just scratching lines on the shifting dunes of eternity?

https://mathwithbaddrawings.com/2015/04/16/metric-time/

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

116 a 130 de 130

Siguiente Anterior

116 a 130 de 130

Siguiente

Último

Último

|