Finest Craftsmanship

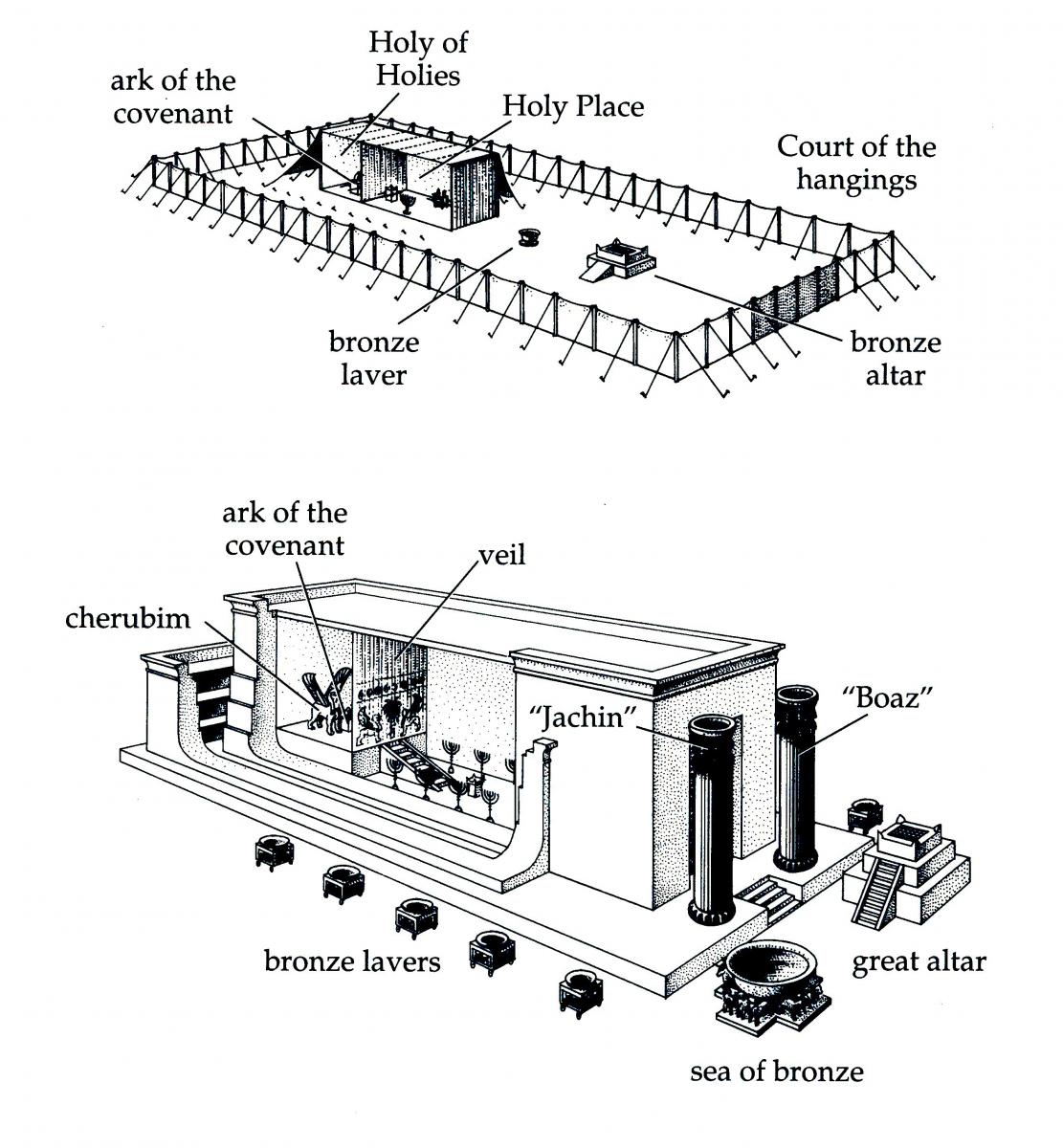

Moses received detailed plans for the Tent of Meeting. Solomon’s Temple was built with a similar room arrangement, but exactly double the size. Solomon had at his command costly and beautiful materials, and he enlisted craftsmen from King Hiram of Tyre, Solomon’s ally and neighbor to the north. Solomon sent a message to Hiram, detailing their agreement as they made the plans to build: “So give orders that cedars of Lebanon be cut for me. My men will work with yours, and I will pay you for your men whatever wages you set. You know that we have no one so skilled in felling timber as the Sidonians.”[8]

King Hiram responded, “I have received the message you sent me and will do all you want in providing the cedar and pine logs.”[9] This was a gigantic project: floating giant cedars of Lebanon from Tyre, a coastal city more than eighty-nine miles north, all the way to Joppa, then hauling them nearly forty miles up the ever-steepening road to Jerusalem. Their arduous overland trek ended 2,550 feet above sea level as they finally arrived in Jerusalem.

After arranging for stonemasons and other craftsman, King Hiram sent the man, also named Hiram (but known as Huram), to direct the work. His mother was an Israelite widow from the tribe of Naphtali and his father was a man of Tyre and a craftsman in bronze. “Huram was filled with wisdom, with understanding and with knowledge to do all kinds of bronze work. He came to King Solomon and did all the work assigned to him” (1 Kings 7:14, NIV).

With expert Phoenician craftsmen directed by Huram, the work proceeded, and after seven years the magnificent structure was finished, with its altar for burnt offerings, its gigantic yam or sea on the backs of twelve oxen for purification of the priests, and the other ten smaller basins on wheels for washing the sacrificial animals. After all of the trappings surrounding the temple were in place, the ark of the covenant was brought by the elders of Israel to be carefully placed in the uppermost room in the temple, the Holy of Holies.

Just as Solomon’s Temple had one man overseeing the construction, so Truman O. Angell oversaw the construction of the Salt Lake Temple. Like Huram of Tyre, he started as a craftsman. Huram was a worker in bronze, while Angell was a carpenter and a joiner. The miracle of the Salt Lake building was that Angell was supervising volunteers, some of whom had received ordinances in the Nauvoo Temple. Their motivation rivaled that of the faithful Saints, who begged Brigham Young to keep the Nauvoo Temple open night and day so that their ordinances might be completed before they journeyed across the continent. They began work on a new, larger Salt Lake Temple, where they knew they could receive the same blessings from the Lord. One major difference in the two temples was that in the Salt Lake Valley, faithful Latter-day Saints did most of the work. In the case of Huram, Phoenician workers formed the labor force, likely supplemented by Israelites pressed into service.

In both instances, only the best materials were employed in the buildings. In Solomon’s time this meant cedar from Lebanon, but in the valleys of the mountains, it meant hauling granite that weighed between 2,500 and 5,600 pounds from a quarry twenty miles from the building site. This was accomplished with only oxen and wagons until 1869, when the railroad came to the territory. While Solomon’s Temple took seven years to build, the Salt Lake Temple was completed after forty years, largely because of the immensity of the task.[10]

Dedicatory Prayers

In the ancient Israelite temple, Solomon himself offered the dedicatory prayer. Solomon stood “before the altar of the Lord in front of the whole assembly of Israel, spread[ing] out his hands toward heaven” (1 Kings 8:22, NIV). Here we see the first and only time that a king of Israel is allowed to perform this priestly function. (King Uzziah attempted to act in the priesthood, but was punished with leprosy as described in 2 Chronicles 26:18–19.)

Solomon began the dedication by acknowledging, “There is no God like you in heaven above or on earth below—you, who keep your covenant of love with your servants who continue wholeheartedly in your way.” In the prayer he goes on to plead that the prayers asked by him and his people may be especially noted as they “pray toward this place” (1 Kings 8:23, NIV). In 1893, Solomon’s words were echoed by President Wilford Woodruff as he dedicated the Salt Lake Temple.

Heavenly Father, when Thy people shall not have the opportunity of entering this holy house to offer their supplications unto Thee, and they are oppressed and in trouble, surrounded by difficulties or assailed by temptation and shall turn their faces towards this Thy holy house and ask Thee for deliverance, for help, for Thy power to be extended in their behalf, we beseech Thee, to look down from Thy holy habitation in mercy and tender compassion upon them, and listen to their cries. Or when the children of Thy people, in years to come, shall be separated, through any cause, from this place, and their hearts shall turn in remembrance of Thy promises to this holy Temple, and they shall cry unto Thee from the depths of their affliction and sorrow to extend relief and deliverance to them, we humbly entreat Thee to turn Thine ear in mercy to them; hearken to their cries, and grant unto them the blessings for which they ask.[11]

Thus both ancient and modern dedications pled with the Lord to give priority to prayers when supplicants were in distress and chose to face the temple. They asked that he would remember his promises, no matter where they were.

Differences in Structure

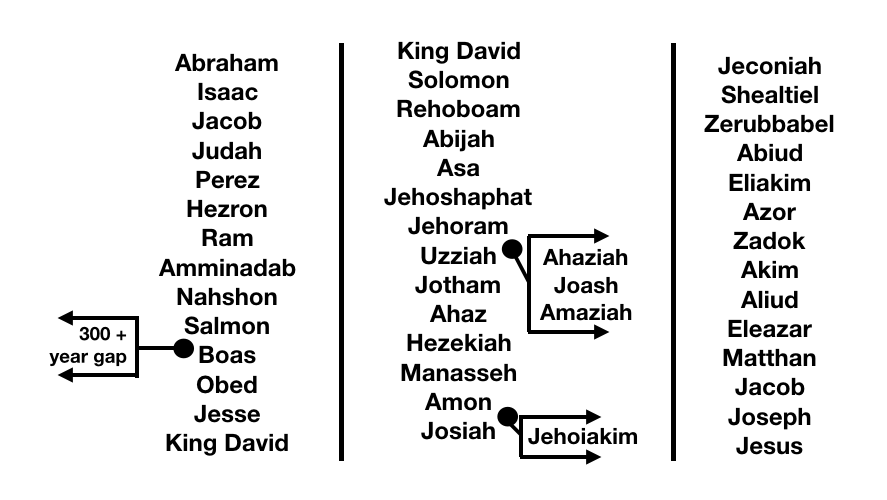

Despite the many similarities between the Temple of Solomon and the Salt Lake Temple, there are significant differences in structure that reflect the function of each temple. The Temple of Solomon was an Aaronic Priesthood temple, and the Salt Lake Temple operates under the Melchizedek Priesthood. Some striking differences between ancient Aaronic Priesthood temples and modern Melchizedek Priesthood temples are outlined in table 1.

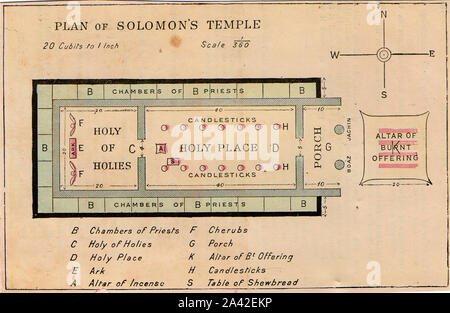

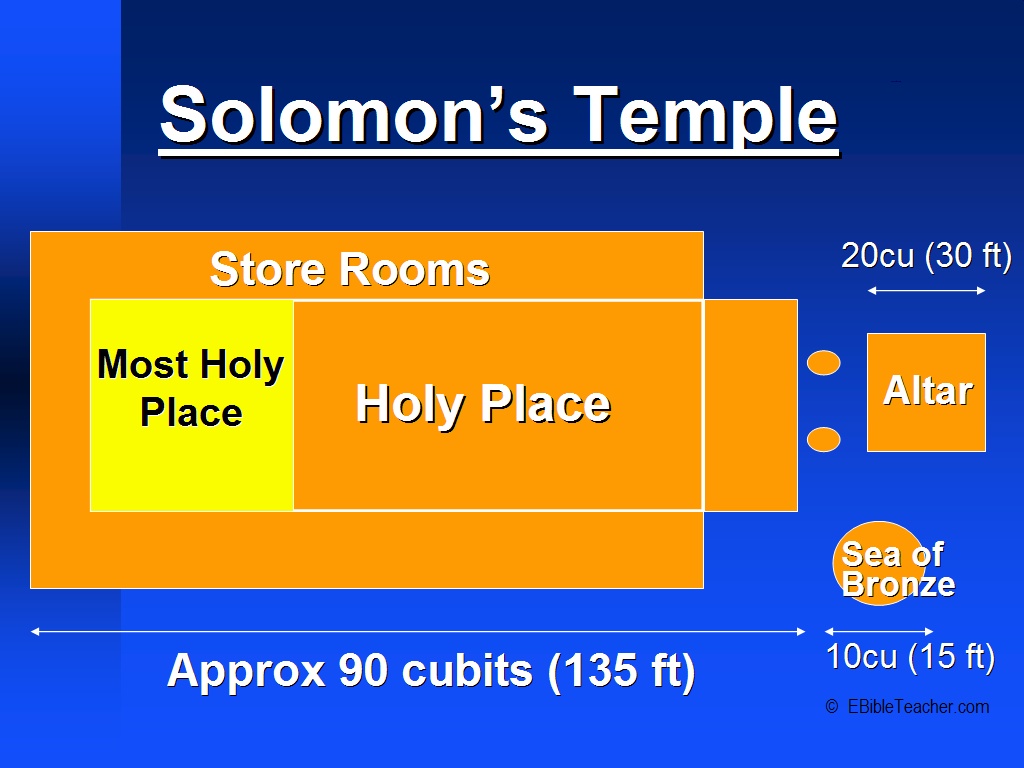

The Temple of Solomon had an exterior courtyard containing an altar for burnt offerings, a “brazen sea” to hold the water for the purification of the priests, and smaller washbasins on wheels to wash the animal sacrifices (see 1 Kings 6). The temple itself had one large room, divided by a curtain into two rooms: the Holy Place, or large main room, and the Holy of Holies (translated from the Hebrew, “Most Holy Place”).[12] The large main room contained a table for the “bread of the Presence,” or literally, the “bread before His face,”[13] translated as “shewbread” in the King James Bible, which was a weekly offering[14] to the Lord (1 Kings 7:48). The room featured ten oil lamps with seven branches in the shape of a tree, which brightly illuminated the large main room. There was a smaller altar burning incense just in front of the steps leading to the Holy of Holies. At the top of the steps hung the curtain separating the large main room from the Holy of Holies, which contained the ark of the covenant, a box for the Ten Commandments, and other relics from Israel’s wilderness days. This box, whose top was called the “mercy seat,” featured two cherubim, and the whole represented the throne of God as noted in Numbers 7:89: “And when Moses was gone into the tabernacle of the congregation to speak with him, then he heard the voice of one speaking unto him from off the mercy seat that was upon the ark of testimony, from between the two cherubims: and he spake unto him.”[15] The ark of the covenant was itself flanked by two huge gold cherubim.

The Salt Lake Temple has many rooms that are used for various ordinances, with many more auxiliary rooms. There are dressing rooms, a creation room, a garden room, a world room, a terrestrial room, a celestial room, sealing rooms, a Holy of Holies, and a chapel, just to mention a few. Most strikingly, perhaps, there is no sacrifice of animals on an altar outside the Salt Lake Temple. Animal sacrifices as dictated by the law of Moses are not performed in this temple. There is no Aaronic high priest, a lineal descendent of Aaron who was the only one who would enter the Holy of Holies once each year on Yom Kippur.

As we consider Solomon’s Temple, we are surrounded by symbols. The decor in the large room called the Holy Place of that temple is comparable to the garden rooms in our modern temples, decorated with trees, flowers, and fruits, but there they are all of gold. The celestial rooms in modern temples and the Holy of Holies in ancient temples both symbolize the presence of God. The lack of a one-to-one correlation of rooms in the temple of Solomon when compared to the Salt Lake Temple shows the distinctly different functions of the two buildings. Most strikingly, perhaps, there is no killing of animals to be sacrificed on an altar outside the Salt Lake Temple.

Sacrifices Offered: Animals vs. “Broken Heart and Contrite Spirit”

The Temple of Solomon required blood sacrifice that was simple and straightforward; the worshippers were to bring their best animal, one that might sire a prize flock of sheep. It would be replaced in the flock by the second best, because the best was to be given to the Lord. A worshipper sacrificed his or her sins with the animal as proxy. It is easy to see the symbol in this of a loving Heavenly Father, who would sacrifice his best to make possible the ultimate forgiveness of our sins, to enable us in the end to be totally clean, “clean every whit” as we read in John 13:10.[16] Temples teach of the Atonement, a complete cleansing from sins.

The Salt Lake Temple contains altars, but no animal sacrifices are offered up on these altars. We learn from the book of Hebrews that Christ is the last great sacrifice and also the high priest who would offer that sacrifice: “For such an high priest became us, who is holy, harmless, undefiled, separate from sinners, and made higher than the heavens; Who needeth not daily, as those high priests, to offer up sacrifice, first for his own sins, and then for the people’s: for this he did once, when he offered up himself” (Hebrews 7:26–27). Also, “Now of the things which we have spoken this is the sum: We have such an high priest, who is set on the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in the heavens; A minister of the sanctuary, and of the true [tent], which the Lord pitched, and not man” (Hebrews 8:1–2).[17]

The Book of Mormon also alludes to this: “Wherefore, redemption cometh in and through the Holy Messiah; for he is full of grace and truth. Behold, he offereth himself a sacrifice for sin, to answer the ends of the law, unto all those who have a broken heart and a contrite spirit; and unto none else can the ends of the law be answered” (2 Nephi 2:6–7).

What was done anciently would be surpassed in modern temples. In D&C 128:18 we read that “those things which never have been revealed since the foundation of the world, but have been kept hid from the wise and prudent, shall be revealed unto babes and sucklings in this, the dispensation of the fulness of times.” What was begun in this dispensation in Kirtland and Nauvoo has expanded into the 143 working temples of our day.[18]

In the Salt Lake Temple, rather than sacrificing an animal to the Lord, worshippers commemorate the sacrifice of the Son of God, the great high priest who offered himself for humanity. Animal sacrifice, in which worshippers symbolically gave away their sins through the literal slaying of a proxy animal, is replaced by the worshippers covenanting to give away their sins by offering a “broken heart and a contrite spirit,” as Jesus explains in 3 Nephi 9:19–20: “And ye shall offer up unto me no more the shedding of blood; yea, your sacrifices and your burnt offerings shall be done away, for I will accept none of your sacrifices and your burnt offerings. And ye shall offer for a sacrifice unto me a broken heart and a contrite spirit.”

“Modern temples restore and transcend the communion of earlier sanctuaries. They require us to bring to the altar what is deepest inside us in the spirit of consecration.”[19] Thus a sacred sacrifice is still required.

Latter-day Ordinances Added: Endowment and Sealing

When worshippers come with their sacrifice of a broken heart and a contrite spirit to modern temples, they receive priceless gifts: the endowment (which literally means “the gift”), the gift of being sealed to their family, and acting as proxy for their dead ancestors to receive all necessary ordinances. Doctrine and Covenant 128:18, referring to ordinances performed in modern temples like the Salt Lake Temple, states that “it is sufficient to know, in this case, that the earth will be smitten with a curse unless there is a welding link of some kind or other between the fathers and the children.” That welding link is the sealing ordinance.

In the Temple of Solomon, worshippers brought a gift to the Lord; in our modern-day temples, worshippers receive a gift from the Lord. It should be noted that some of the ordinances performed in temples since the Restoration were available to a chosen few anciently but were likely given on mountain tops or in other venues. Perhaps persons were even isolated in a dimension the naked eye could not penetrate without being enhanced by God’s power (see Ether 3:19; Matthew 17:1–8). Some have speculated that worshippers were endowed or sealed to their families in the Temple of Solomon, but President Brigham Young, speaking at the dedication of the St. George Temple, said, “It is true that Solomon built a Temple for the purpose of giving endowments, but from what we can learn of the history of that time they gave very few if any endowments.”[20]

When and where could they have performed these sealing ordinances? There would have been priests offering sacrifices, morning and night, as noted in Leviticus 6:20. The priests would also have kept worshippers out of the temple proper, since only one man, the Aaronic high priest, was allowed to go into the Holy of Holies. It should be noted that the Salt Lake Temple has a Holy of Holies, just as the Temple of Solomon did, but they serve different functions. Solomon’s Holy of Holies was the symbolic presence of God where the ark of the covenant sat, the Lord’s throne-room. In the Salt Lake Temple, the celestial room symbolizes an individual’s entering into the presence of the Lord, while the Holy of Holies is reserved for a different function. As Lysle R. Cahoon has pointed out, “A latter-day Holy of Holies has been dedicated in the great temple in Salt Lake City. The presiding high priest, the President of the Church, controls access to this sanctuary (room).”[21]

Who Can Enter Each Temple?

The law-of-Moses temples were operated only by men born into a bloodline that made them heirs to the Aaronic/Levitical Priesthood (Exodus 28). Their leader was called a high priest and was a literal descendant of Aaron. The Aaronic Priesthood high priest was the only one who entered the most sacred room in that building, the Holy of Holies, once a year on the Day of Atonement, as recorded in Leviticus 16. The altar just outside of the temple was the place where sacrifices prescribed in the law of Moses were offered. Worshippers could only go as far as the courtyard. They then would participate in killing the offering and would leave the rest to the priest, as explained in Leviticus 1:4–5: “And he [the worshiper] shall put his hand upon the head of the burnt offering; and it shall be accepted for him to make atonement for him. And he shall kill the bullock before the Lord: and the priests, Aaron’s sons, shall bring the blood, and sprinkle the blood round about upon the altar that is by the door of the [tent of meeting].” The priest then proceeded to partake of the sacred meal, which comprised the meat of the animal offered and a bread offering. This was sometimes shared with the one who brought the offering.

In the Salt Lake Temple, the invitation to eat a symbolic sacred meal (the sacrament) is sometimes extended to worthy members of the Church during solemn assemblies held there in a large assembly room on the third floor. But members are usually invited to partake of the sacrament weekly in their local chapels.

Although temples in this dispensation operate under a Melchizedek Priesthood high priest (a prophet who holds the keys that were restored to Joseph Smith), he is not the only one to worship inside. The rooms of these temples are entered by multitudes of worthy men who hold the Melchizedek Priesthood, as well as worthy women. Even children over the age of twelve are busy in the baptismal fonts, acting on behalf of the dead, who are unable to complete this essential ordinance for themselves. Even younger children come inside to be sealed to their parents. In modern temples, worshippers do not have to stop outside the doors of the temple to wait for a priest to do everything for them. A worshipper may progress through all the rooms of the temple, finally entering into the symbolic presence of the Lord, a privilege denied to the ancient Israelites. In the Salt Lake Temple, sacrifice is a way station on the way to consecration.

In temples like the Salt Lake Temple, people receive their own endowments to begin to claim their inheritance. In Nauvoo, more of the fulness of that inheritance was rolled out. It was this mighty motivation that enabled pioneers to cross a continent, having received the promises of the endowment of power. That power continues to enable over 82,000 missionaries to meet the challenges of our day as they open the door of baptism to hundreds of thousands who step out of baptismal fonts, beginning their own pioneer journey to the temple.

Anciently, the children of Israel were not willing to accept Moses’ invitation to meet God on the top of the mountain.[22] Today prophets regularly invite each member to come to the temple. The choice is as real as it was to those ancient Israelites: whether or not to ascend the mountain to meet the Lord.

Proxy Ordinances

In the Temple of Solomon, the sacrificial animal was proxy for the worshipper’s sins, as noted in Leviticus 1:4: “And he shall put his hand upon the head of the burnt offering; and it shall be accepted for him to make atonement for him.” But the priest also acted as proxy for the Israelites by performing ordinances on their behalf, as noted in Leviticus 1:4–5, discussed above. Once each year the priest cleansed all the people by proxy on the Day of Atonement, as dictated in Leviticus 16:17: “And there shall be no man in the [tent of meeting] when he goeth in to make an atonement in the holy place, until he come out, and have made an atonement for himself, and for his household, and for all the congregation of Israel.”

In the Salt Lake Temple, however, worshippers participate in the ordinances themselves. Worshippers also perform proxy ordinances in behalf of the dead, participating in all the ordinances from baptism to sealings. In the Temple of Solomon, the differing socioeconomic status of the worshippers would have been painfully obvious. The rich would have offered more costly offerings than the poor, as noted in Leviticus 5:7: “And if he be not able to bring a lamb, then he shall bring for his trespass, which he hath committed, two turtledoves, or two young pigeons, unto the Lord; one for a sin offering, and the other for a burnt offering.”

In the Salt Lake Temple, all individuals, from the most affluent to the most indigent, wear the same white clothing. This is a reminder to the worshipper of equality before the Lord, as noted in 2 Nephi 26:33: “He inviteth them all to come unto him and partake of his goodness; and he denieth none that come unto him, black and white, bond and free, male and female; and he remembereth the heathen; and all are alike unto God, both Jew and Gentile.”

Covenants Help Perfect and Unite

In all temples it is the covenants that unite us with each other and with the Lord. In Moses’ time, the rituals of the law of Moses were associated with covenants, as in Exodus 24:7–8: “And he took the book of the covenant, and read in the audience of the people: and they said, All that the Lord hath said will we do, and be obedient. And Moses took the blood, and sprinkled it on the people, and said, Behold the blood of the covenant, which the Lord hath made with you concerning all these words.”

Ancient Israelites were referred to as a covenant people. The people promised to keep the covenants recorded in the law of Moses. The Ten Commandments outlined what they should and should not do and were referred to as the covenants of the Lord, but they were not the only agreements they had made with the Lord. In Leviticus 26:42, he reminds them, “Then will I remember my covenant with Jacob, and also my covenant with Isaac, and also my covenant with Abraham will I remember; and I will remember the land.” So the blessings of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob were part of an eternal covenant. The land that was promised, the power in exercising the priesthood, and an endless posterity were all part of that covenant. “For I will have respect unto you, and make you fruitful, and multiply you, and establish my covenant with you” (Leviticus 26:9).

In Deuteronomy 5:2–3 it is obvious that these covenants were personal. “The Lord our God made a covenant with us in Horeb [Sinai]. The Lord made not this covenant with our fathers, but with us, even us, who are all of us here alive this day.”

The box containing the tablets was known as the ark of the covenant. Solomon tied the temple to this covenant in 1 Kings 8:21: “And I have set there a place for the ark, wherein is the covenant of the Lord, which he made with our fathers, when he brought them out of the land of Egypt.” However, in Jeremiah 31:31–33, in speaking of a new covenant that will be made in days to come, he explains that the earlier covenant had been broken.

Behold, the days come, saith the Lord, that I will make a new covenant with the house of Israel, and with the house of Judah;

Not according to the covenant that I made with their fathers in the day that I took them by the hand to bring them out of the land of Egypt; which my covenant they brake, although I was an husband unto to them, saith the Lord:

But this shall be the covenant that I will make with the house of Israel; After those days, saith the Lord, I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts; and will be their God, and they shall be my people.

In April 1830, the same month that the Church was formally organized, the Lord spoke concerning the ordinance of baptism in a new way. D&C 22:1 teaches: “Behold, I say unto you that all old covenants have I caused to be done away in this thing; and this is a new and an everlasting covenant, even that which was from the beginning.”

After the covenant one makes at baptism, having been cleansed from sins, it is making and keeping further covenants that move a person towards Christ. This involves a new and everlasting way of covenanting. Cleansing must continue if we are to one day enter the Lord’s presence. Christ’s Atonement and its enabling power to transform are essential in this plan. The new and everlasting covenant of marriage described in D&C 131:2 and D&C 132 is also central to the plan of salvation. How did the Lord intend to put his law “in [our] inward parts and write it in [our] hearts?” Is a “broken heart and a contrite spirit” what the Lord is referring to when he speaks of putting his law deep within us and writing it on our hearts? Latter-day Saints are invited to be a covenant-keeping people by bringing the sacrifice to their temples of exactly that: “a broken heart and a contrite spirit.”

Conclusion

Obedience and sacrifice, as taught in the law of Moses, were the twin pillars of worship in ancient Aaronic Priesthood temples, like the Temple of Solomon. They were intended to direct the Israelites’ minds forward to the coming of Christ and his infinite obedience and sacrifice. Building on these profound concepts, our modern temples are the fulness of what the ancient prophets longed for, as they looked forward with great anticipation to this last dispensation.

We read in D&C 27:13 of keys being committed to men in our time: “Unto whom I have committed the keys of my kingdom, and a dispensation of the gospel for the last times; and for the fulness of times, in the which I will gather together in one all things, which are in heaven, and which are on earth.”

Today Christ invites all to the temples the prophets of old envisioned, to learn, through covenants, how to become holy, sanctified, and clean, receiving his image in their countenances. “Beloved, now are we the sons of God, and it doth not yet appear what we shall be: but we know that, when he shall appear, we shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is. And every man that hath this hope in him purifieth himself, even as he is pure” (1 John 3:2–3).

He has always invited all to come to meet him so that they can learn how to become like him. Indeed, all may know him and feel the power he has to make them clean through his infinite Atonement. As described in Jeremiah 31:34, “And they shall teach no more every man his neighbour, and every man his brother, saying, Know the Lord: for they shall all know me, from the least of them unto the greatest of them, saith the Lord: for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more” (emphasis added).

Each ordinance helps us know Christ better. Covenants mark the path to his infinite goodness. One comes to learn of holiness and leaves endowed with power, amazingly able to inherit all that he has. The temple is the way to learn how to qualify to receive the eternal inheritance he has promised.

Beginning with the garden motif in Solomon’s temple, modern temples move beyond that symbolism. Modern temples start where ancient temples left off. Ancient temples seem to be symbolic of the garden of the Lord and a Holy of Holies where God’s throne is glimpsed through a veil. The temples of this day move through several more rooms to accommodate the additional ordinances that were yet to be revealed in this dispensation of the fulness of times. Consider the progression through these rooms, ending in a room above the rest representing the celestial kingdom, our heavenly destination, where we will be welcomed by a Heavenly Father who has given us temples to find our way back to his holy presence.

Many years ago I wrote these lines, which summarize an experience in the Salt Lake Temple:

In the Temple

The quiet closes ’round me

like fog.

God’s house reverberates

with silence,

filled with echoes

from the faithful

who have followed the light

to here, like a star.

White unites us

in this place

of radiant light.

Dear Host

of this heavenly house,

if I come,

clothed in the pure white

of a new lamb,

with my heart as new,

may I too

be lighted?

Table 1. Ancient and Modern Temples Compared

|

Temple of Solomon—Aaronic Priesthood

|

Salt Lake Temple—Melchizedek Priesthood

|

| One man, the Aaronic Priesthood high priest, enters Holy of Holies, the symbolic presence of God. (Leviticus 16) |

Any worthy member of the Church may enter into the celestial room, the symbolic presence of God. |

| High priest only enters room representing presence of God once a year. (Leviticus 16) |

All worthy members may enter room representing presence of God whenever they participate in the endowment. |

| Only male descendants of Levi and specifically of Aaron officiate in temple. (Exodus 28) |

Men and women of all Israel officiate in temple. |

| Sacrifices given. (Leviticus 1) |

Endowment received. Sealings performed. |

| Sacred meal. (Leviticus 2) |

Sacred meal weekly in sacrament meeting and occasionally in solemn assemblies.

(1 Corinthians 11:24)

|

| Proxy animals offered for sins of the living. (Exodus 29) |

Proxy work of the living in behalf of the dead. (D&C 138:33) |

| Priest helps individuals by performing sacrifices. (Leviticus 2:2) |

Individuals help the dead by proxy ordinances. |

| Blood of animals sacrificed. (Leviticus 1:5) |

The Atonement of Christ, symbolized by his bleeding on our behalf—once and for all. (D&C 19:16–19) |

| Animals are the sacrifices. (Leviticus 1) |

Sacrifice: broken heart and a contrite spirit. (D&C 59:8) |

| Sacrifices varied from person to person, depending on economic status and sin being forgiven. (Leviticus 5:7) |

Same sacrifice required of all. All worthy and dressed in white to help teach that “all are alike unto God.” (2 Nephi 26:33) |

| Marriage not part of temple worship. |

Eternal marriages sealed at altars for that purpose. |

Notes

Special thanks to Jonathon Riley, research assistant, whose patient help has been invaluable.

[1] Ohel moed is a common phrase and appears more than one hundred times in one form or another.

[2] Truman G. Madsen, Presidents of the Church (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2004), 141–42.

[3]“Temple of Solomon,” Jewish Encyclopedia, accessed September 15, 2014, http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/articles/14310-temple-of-solomon.

[4] Joseph Smith, comp., History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1961), 1:357.

[5] Michael Avi-Yonah, “Moriah,” in Encyclopaedia Judaica, ed. Michael Berenbaum and Fred Skolnik, 2nd ed. (Detroit: Macmillan Reference, 2007), 14:491.

[6] See 1 Kings 6 and 2 Chronicles 3–6.

[7] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses, 1:133 (at laying of cornerstone for Salt Lake Temple, April 6, 1853).

[8] 1 Kings 5:6 (NIV).

[9] 1 Kings 5:8 (NIV).

The Salt Lake Temple, a modern-day house of the Lord. (Charles Roscoe Savage, Church History Library.)

The Salt Lake Temple, a modern-day house of the Lord. (Charles Roscoe Savage, Church History Library.) Tent of Meeting. (Illustration by Michael P. Lyon. Reproduced courtesy of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University.)

Tent of Meeting. (Illustration by Michael P. Lyon. Reproduced courtesy of the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship, Brigham Young University.) Plan of the Camp of Israel with the Tent of Meeting at the Center. (Courtesy of Preston Heiselt.)

Plan of the Camp of Israel with the Tent of Meeting at the Center. (Courtesy of Preston Heiselt.)

![That's one small step..." —Neil Armstrong [1024 x 1333] : r/QuotesPorn](https://i.imgur.com/lfLGX.jpg)