|

|

Vézelay Abbey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vézelay Abbey (French: Abbaye Sainte-Marie-Madeleine de Vézelay) is a Benedictine and Cluniac monastery in Vézelay in the east-central French department of Yonne. It was constructed between 1120 and 1150. The Benedictine abbey church, now the Basilica of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine (Saint Mary Magdalene), with its complex program of imagery in sculpted capitals and portals, is one of the great masterpieces of Burgundian Romanesque art and architecture.[1] Sacked by the Huguenots in 1569, the building suffered neglect in the 17th and the 18th centuries and some further damage during the period of the French Revolution.[2]

The church and hill at Vézelay were added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1979 because of their importance in medieval Christianity and outstanding architecture.[1]

Relics of Mary Magdalene can be seen inside the Basilica.

History[edit]

The Benedictine abbey of Vézelay was founded,[3] as many abbeys were, on land that had been a late Roman villa, of Vercellus (Vercelle becoming Vézelay). The villa had passed into the hands of the Carolingians and devolved to a Carolingian count, Girart, of Roussillon. The two convents he founded there were looted and dispersed by Moorish raiding parties in the 8th century, and a hilltop convent was burnt by Norman raiders. In the 9th century, the abbey was refounded under the guidance of Badilo, who became an affiliate of the reformed Benedictine order of Cluny. Vézelay also stood at the beginning of one of the four major routes through France for pilgrims going to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, in the north-western corner of Spain.

About 1050 the monks of Vézelay began to claim to hold the relics of Mary Magdalene, brought, they said, from the Holy Land either by their 9th-century founder-saint, Badilo, or by envoys despatched by him.[4] A little later a monk of Vézelay declared that he had detected in a crypt at St-Maximin in Provence, carved on an empty sarcophagus, a representation of the Unction at Bethany, when Jesus' head was anointed by Mary of Bethany, who was assumed in the Middle Ages to be Mary Magdalene. The monks of Vézelay pronounced this to be Mary Magdalene's tomb, from which her relics had been translated to their abbey. Freed captives then brought their chains as votive objects to the abbey, and it was the newly elected Abbot Geoffroy in 1037 who had the ironwork melted down and reforged as wrought iron railings surrounding the Magdalene's altar.[4] Thus the erection of one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture which followed was made possible by pilgrims to the declared relics and these tactile examples demonstrating the efficacy of prayers. Mary Magdalene is the prototype of the penitent, and Vézelay has remained an important place of pilgrimage for the Catholic faithful, though the actual claimed relics were torched by Huguenots in the 16th century.

Floorplan of Vézelay shows the adjustment in vaulting between the choir and the new nave.

To accommodate the influx of pilgrims a new abbey church was begun, dedicated on April 21, 1104, but the expense of building so increased the tax burden on the abbey's lands that the peasants rose up and killed the abbot. The crush of pilgrims was such that an extended narthex (an enclosed porch) was built, inaugurated by Pope Innocent II in 1132, to help accommodate the pilgrim throng.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux preached at Vézelay in favor of a second crusade at Easter 1146, in front of King Louis VII. Richard I of England and Philip II of France met there and spent three months at the Abbey in 1190 before leaving for the Third Crusade. Thomas Becket, in exile, chose Vézelay for his Whitsunday sermon in 1166, announcing the excommunication of the main supporters of his English King, Henry II, and threatening the King with excommunication too. The nave, which had been burnt once, with great loss of life, burned again in 1165, after which it was rebuilt in its present form.

The abbey's self-assured monastic community was prepared to defend its liberties and privileges against all comers:[5] the bishops of Autun, who challenged its claims to exemption; the counts of Nevers, who claimed jurisdiction in their court and rights of hospitality at Vézelay; the abbey of Cluny, which had reformed its rule and sought to maintain control of the abbot within its hierarchy; the townsmen of Vézelay, who demanded a modicum of communal self-government.

The beginning of Vézelay's decline coincided with the well-publicized discovery in 1279 of the body of Mary Magdalene at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume in Provence, given regal patronage by Charles II, the Angevin king of Sicily. When Charles erected a Dominican convent at La Sainte-Baume, the shrine was found intact, with an explanatory inscription stating why the relics had been hidden. The local Dominican friars compiled an account of miracles that these relics had wrought. This discovery undermined Vézelay's position as the principal shrine of the Magdalene in Europe.

After the Revolution, Vézelay stood in danger of collapse. In 1834 the newly appointed French inspector of historical monuments, Prosper Mérimée (more familiar as the author of Carmen), warned that it was about to collapse, and on his recommendation the young architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was appointed to supervise a massive and successful restoration, undertaken in several stages between 1840 and 1861, during which his team replaced a great deal of the weathered and vandalized sculpture. The flying buttresses that support the nave are his.[6]

Interpretation of the tympanum[edit]

The tympanum of the central portal of the Madeleine de Vézelay is different from its counterparts across Europe. From the beginning, its tympanum was specifically designed to function as a spiritual defense of the Crusades and to portray a Christian allegory to the Crusaders' mission. When compared to contemporary churches such as St. Lazare d'Autun and St. Pierre de Moissac, the distinctiveness of Vézelay becomes apparent.

The art historian George Zarnecki wrote, "To most people the term Romanesque sculpture brings to mind a large church portal, dominated by a tympanum carved with an apocalyptic vision, usually the Last Judgment."[7] This is true in most cases, but Vézelay is an exception. In a 1944 article, Adolf Katzenellenbogen interpreted Vézelay's tympanum as referring to the First Crusade and depicting the Pentecostal mission of the Apostles.[8]

Thirty years before the Vézelay tympanum was carved, Pope Urban II planned on announcing his call for a crusade at La Madeleine[citation needed]. In 1095, Urban altered his plans and preached for the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont, but Vézelay remained a central figure in the history of the crusades. The tympanum was completed in 1130. Fifteen years after its completion, Bernard of Clairvaux chose Vézelay as the place from which he would call for a Second Crusade. Vézelay was even the staging point for the Third Crusade. It is there that King Richard the Lionheart of England and King Philip Augustus of France met and joined their armies for a combined western invasion of the holy land. It is appropriate, therefore, that Vézelay's portal reflect its place in the history of the crusades.

The art historian Peter Low argues for the central tympanum as a visualization of both the Pentecost and a passage from book of Ephesians chapter 2—proclaiming to the visiting laity the tenets of Benedictine monasticism and to visiting pilgrims the extent and reach of a universalizing church that welcomes "the full, even monstrous range of the globe's inhabitants."[9]

Detail of right side

The lintel of the Vézelay portal portrays the "ungodly" people of the world. It is a depiction of the first Pentecostal Mission to spread the word of God to all the people of the world. The figures in the tympanum who have not received the Word of God are depicted as not fully human. Some are shown with pig snouts, others are misshapen, and several are depicted as dwarves. One pygmy in particular is depicted as mounting a horse with the assistance of a ladder. On the far right, there is a man with elephantine ears, while in the center we see a man covered in feathers. The architects and artisans depicted the unbelievers as physically grotesque in order to provide a visual image of what they saw as the non-believers' moral turpitude. This is a direct reflection of Western perceptions of foreigners such as the Moors, who were being specifically targeted by the Crusaders. Even Pope Urban II, in his call for a crusade, helped promote this ethnocentric perception of the Turks by calling on westerners to, "exterminate this vile race."[10] Most Westerners had absolutely no idea what the Turks and Muslims looked like, and they assumed that an absence of Christianity must coincide with repulsive physical attributes. It has also been argued that the disbelievers were carved as deformed monsters in an effort to dehumanize them. By dehumanizing their enemies in art, the Crusaders' mission to capture the holy land and convert or kill the Muslims was glorified and sanctified. The Vézelay lintel is, therefore, a political statement as well as a religious one.

Lower compartments[edit]

Detail of centre

The lower four compartments of the Vézelay tympanum show the nations that had already received the Gospels. They include the Byzantines, Armenians, and Ethiopians. The inclusion of the Byzantines is particularly important because it was the Byzantines who initially requested a Crusade to the holy land. The Byzantines had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuk Turks through warfare, and they were eager to seek western military support to reclaim that territory.

The characters in the lower Vézelay compartments are regal and well proportioned. They are a direct contrast to their "heathen" counterparts in the lintel. They are human as opposed to monstrous. In the eyes of the designers, they had received God's grace and are thus pictured as fully human in every detail. These compartments can, therefore, can be seen as an allegory for the crusading nations. The Crusader armies were made up of many different nationalities bound only by faith in the same God. Nations that had previously warred with one another were suddenly united for a common goal. The lower tympanum compartments are an expression of this newfound solidarity.

Central portal[edit]

The central portal

The central portion of the Vézelay tympanum continues this process of politicizing religion. The central tympanum shows a benevolent Christ conveying his message to the Apostles, who flank him on either side. This Christ is distinct in Romanesque architecture. He is a stark contrast to the angry Christ of the St. Pierre de Moissac tympanum. The Moissac Christ is a forbidding figure that sits upon the throne of judgment. It is another example of the typical Romanesque Christ. His face is without caring or emotion. He holds the scrolls containing the deeds of mankind, and he stands ready to execute punishment on the damned. The Vézelay Christ, however, is pictured contraposto with arms wide. He is delivering a message, not exacting punishment. The Vézelay tympanum is remarkable because it is so different. The Vézelay Christ is sending the Crusaders out—he is not judging them. Indeed, the Crusaders were guaranteed remission of all sins if they participated in the Crusades. A forbidding Christ placed upon the throne of judgment would have been out of place at Vézelay. That is why the traditional Romanesque Christ, with its angry stare, was replaced at Vézelay by a kind and welcoming Christ with arms wide open.

Astronomical alignment[edit]

Looking east through nave on 23 June 1976, two days after the summer solstice  Mary Magdalene's relics in the crypt

In 1976, Hugues Delautre, one of the Franciscan fathers charged with stewardship of the Vézelay sanctuary, discovered that beyond the customary east-west orientation of the structure, the architecture of La Madeleine incorporates the relative positions of the Earth and the Sun into its design. Every June, just before the feast day of Saint John the Baptist, the astronomical dimensions of the church are revealed as the sun reaches its highest point of the year, at local noon on the summer solstice, when the sunlight coming through the southern clerestory windows casts a series of illuminated spots precisely along the longitudinal center of the nave floor.[13][14][15][16][17]

See also[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

CURIOSIDADES Y ANECDOTAS

Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes. Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes.

Su verdadero nombre era Myriam, María en hebreo. Para algunos es de origen egipcio, en ese caso significaría “amada de Dios.” Para otros significa: mar amargo, iluminada o iluminadora.

Magdalena o Magdala es un sobrenombre, según algunos es una derivación del sustantivo arameo Migdal (torre). Para otros, deriva del griego Magdalini, basándose en que los evangelios canónicos se transmitieron en esa lengua.

Para varios historiadores, la Magdalena descendía de la tribu de Benjamín, una de las doce tribus de Israel.

La fecha del 22 de julio, aparece en el martirologio anglosajón del monje Oengo, como: La Sagrada Natividad de María Magdalena. Y el 28 de marzo como: La Fiesta de su Conversión a Cristo.

En el siglo III, Hipólito, obispo de Roma, le otorga el título de Apostola Apostolorum (Apóstol de los apóstoles). Para él es la “Nueva Eva”, por la que la iglesia de los judíos, representada por la primera Eva, es ahora superada y glorificada por la Iglesia de Cristo, encarnada en Santa María Magdalena.

Los colores litúrgicos de su festividad son el blanco y el oro, como símbolo de los contemplativos.

Se cree que Juan el Bautista, comenzó su predicación en Betania, el pueblo de Marta, María y Lázaro.

Magdala, era una ciudad situada a los pies lago Tiberíades o mar de Galilea, que también era conocida por los nombres de Tariquea (que significa “pesca salada” en griego) o Dalmanuta y Gabara. En ella existían hasta ochenta hilaturas de lana fina. Era una de las tres ciudades de Galilea que aportaba una mayor contribución al Templo, hasta tres carros llenos.

Algunos historiadores, afirman que seis días antes de la Última Cena, María de Magdala ungió a Jesús en Betania. Para Mateo y Marcos esto ocurrió sólo dos días antes.

Según varios estudiosos, la Magdalena estuvo presente en el juicio a Jesús.

Según “La Contemplación” en el hogar de María de Magdala se reunieron la Virgen y las otras mujeres durante la flagelación de Cristo.

La “tradición occidental” afirma que la Magdalena llegó en una pequeña nao, junto con sus hermanos y otros cristianos, a las costas de Francia. Concretamente a un pequeño pueblo, llamado hoy “Les Saintes Maries de la Mer”, hacia el año 40 del s.I.

Si alzamos una línea recta imaginaria hacia el cielo, desde las catedrales de Francia junto a la Basílica de La Magdalena, en Vézelay, entre todas forman la conjunción de Virgo, dedicada a la Virgen María.

Desde el siglo IV hasta el siglo XIII, la comunidad religiosa de los casianistas – fundada por el presbítero Casiano-, fueron los custodios de las reliquias de la Santa, conservadas en la cripta de San Víctor. Hoy se encuentran en San Maximino (Aix -en Provence, Francia) dentro de una gran urna rematada con una escultura de bronce que representa a la Magdalena en éxtasis, obra de Alessandro Algardi.

Tras la invasión de Francia por los sarracenos en el siglo VIII, las reliquias de la Santa reaparecen el 4 de Diciembre de 1279, en la cripta de San Maximino.

En el medioevo comienza a ser representada con el tarro o alabastrorum, que significa el Eterno Femenino, el contenedor de la vida y la muerte. Anteriormente era representada con los clavos de la cruz de Cristo en sus manos, popularmente llamada “la Virgen de los clavos”.

Se dice que el tarro con que ungió a Cristo estuvo en la iglesia de San Víctor, en Marsella, según testimonio de Silvestro de Prierio en 1497. El monasterio de Saint Sever en Las Landas, afirmaba poseer parte del ungüento.

San Anselmo de Canterbury, en 1081, le dedica oración lírica.

En el 1103 el papa Pascual II, promulga una bula por la que autoriza la romería en su honor en Vézelay, y estimula al pueblo para aumentar la devoción a la Santa.

San Jerónimo le atribuye el epíteto “fortificada con torres”.

El 6 de marzo de 1058, el papa Etienne IX promulga una bula, donde afirma que el cuerpo de Santa María Magdalena, reposa en la abadía de Vézelay (Borgoña, Francia).

El santuario occidental más antiguo – de finales del siglo X- erigido en honor a la Santa, fue el de Halberstadt, en Alemania. En 1205 el obispo de ese lugar, Conrad de Krosik, regresó de la Cuarta cruzada y trajo consigo diferentes reliquias, entre ellas parte del cráneo de María Magdalena. La llegada de la reliquia se celebra el 17 de agosto.

Hacia 1155 la familia Baffo o Baffa decía poseer un dedo de la Santa y mandó construir en Canaregio, la primera iglesia veneciana, en su honor, para albergar la reliquia. La iglesia se llamaba “Santa María Maddalena Penitente”. Más tarde, en el siglo XVI, fue decorada con cuadros de Tintoretto. Según el historiador de la época, Francisco Sansovino, era la última iglesia que se visitaba durante las celebraciones del Viernes Santo.

A principios del siglo XII se le dedicó una iglesia en Jerusalén, situada en el barrio judío. Se menciona otra iglesia en su honor hacia el 1101-1102 en Ascalón. También existía en Jerusalén un convento dedicado a la Santa donde se alojaban peregrinas, hacia el siglo XII.

Bernardo de Claraval, (San Bernardo) define las reglas de la Orden de los templarios, en ellas encomienda obediencia a Betania, al castillo de Marta y María.

Tras el mandato de disolución de la Orden templaria, algunos de ellos se hallaban cautivos en el Rosellón. Fueron castigados el día 22 de julio de 1307, festividad de Santa María Magdalena.

San Bernardo llegó a escribir hasta noventa sermones acerca del Cantar de los Cantares, una de las lecturas litúrgicas de la festividad de Santa María Magdalena.

San Bernardo, el 31 de marzo de 1146, predicó la Segunda cruzada en la Magdalena de Vézelay, delante del rey Luis VII y su esposa Leonor de Aquitania, los condes de Dreux, de Flandes, de Toulouse y de Nevers. Años después, en 1190, Ricardo Corazón de León (hijo de Leonor de Aquitania y de Enrique II de Inglaterra) y Felipe Augusto se reunieron en el mismo lugar para disponer la Tercera cruzada.

En el año 1183 Felipe Augusto, expulsó a los judíos de París, y trasformó su sinagoga en una iglesia en honor La Magdalena. Estaba situada en la rue de Juiverie. Hoy no existe, en su lugar hay un hotel.

San Luis, rey de Francia, acude a la Sainte- Baume en 1254. En ella se cree que La Magdalena vivió durante diecisiete años. Antes de partir hacia Tierra Santa, en 1267, el rey acudió a Vézeley, para pedir protección a la Santa.

En Francia durante la Edad Media, se celebraba el traslado de sus reliquias desde la Provenza a Vézelay. Allí se festejaba, el 19 de marzo, y en la Provenza el 5 de mayo.

La iglesia de San Maximino de Provenza, guarda los cabellos de la Magdalena, en un relicario, dentro de un vaso de cristal. Esta reliquia atrae la devoción de los fieles. Su largura y su color- rubio tostado- inspiraron durante siglos su iconografía.

Leonor de Aquitania se retiró a la abadía de Fontevrault (Orleáns, Francia) fundada el 15 de abril de 1113, por Luis VI le Gros -cuya patrona era Santa María Magdalena. El 10 de abril de 1257, el papa Alejandro IV concede cuarenta horas de indulgencia, a las personas que visiten la iglesia y el hospicio de Fontevrault, el 22 de julio, festividad de Santa María Magdalena.

A partir del siglo XIII los reyes franceses fueron los patronos de la iglesia de San Maximino donde estaban las reliquias de la Santa. En ese mismo siglo fundaron el Convento Real bajo los cuidados de los dominicos. Ya en el siglo XIX el padre Lacordaire, reinstalo -tras años de ausencia- a los Hijos de Santo Domingo como la escolta de honor de la Magdalena.

Rodolfo de Worms fundó 1224 la Orden especial de penitentes de Santa María Magdalena. Aprobada por el papa Gregorio IX en 1227. Regla agustiniana; vestían hábito blanco. Se las denominaba Weissfrauen, Dames Blanches, o Damas Blancas. A partir de ahí nacieron más de cuarenta conventos en Alemania.

Durante el primer tercio del siglo XIII, el duque Adolfo de Slesvig-Holstein funda en Hamburgo, un convento dedicado a la Santa. Entrará en él como monje en 1239, y vivió allí hasta su muerte en 1261.

Hacia 1230-1306 el franciscano italiano, Jacopone da Todi, le compone un himno, donde María Magdalena se convierte en el consuelo de la Virgen.

Petrarca, entre 1330-1353, la describe como la Dulcis amica Dei (dulce amiga de Dios).

En 1328, Pierre Causit funda en Montpellier (Francia) un hospital cuya patrona es Santa María Magdalena.

Durante el siglo XIII la abadía de San Millán de la Cogolla (La Rioja), poseía varias reliquias de la Santa.

El libro de horas de Carlos VIII de Francia (1470-1498) contiene una miniatura que representa al Rey de rodillas, mientras La Magdalena le presenta ante Cristo.

A finales del siglo XIII, Charles de Salerne, graba su nombre en la chsse (relicario) que guarda las reliquias de la Santa, cincelado a mano y ornamentado en diamantes y zafiros.

La metáfora de Cristo como un jardinero que siembra la semilla en María Magdalena, la recoge el himno pascual de Felipe de Gréve, canciller de Paris en el siglo XIII.

En Inglaterra, a finales del siglo XIII, siete de los once santuarios dedicados a La Magdalena, son hospitales. A menudo se les conoce como “Lazare House” (la casa de Lázaro).

En el monasterio de Saint- Albans, en Herefordshire (Inglaterra) conservaba a finales del siglo XIV varias reliquias de Santa María Magdalena. Éstas se hallan inscritas en un manuscrito que se conserva en el British Museum. Dicho manuscrito fue publicado por Dugdale.

La importancia de Santa María Magdalena en Venecia lo demuestra su aparición en una bandera del siglo XV, junto a San Juan Bautista, San Juan Evangelista y San Jerónimo, todos ellos junto al león de San Marcos.

En Barcelona, a mediados del siglo XV, había una iglesia dedicada a La Magdalena. Donde el sacerdote Miguel Cuberta, ofició su primera misa.

Una bula del 22 de julio de 1435, concedida por el papa Eugéne IV, otorga indulgencia plenaria, en artículo mortis, a todos los habitantes de Arlés y Aix et Embrum (Francia), que ofrezcan sus bienes, para continuar la obra de la iglesia de Santa María Magdalena.

El rey René d´ Anjou, en marzo de 1438, peregrinó a la Sainte-Baume, (Aix- en- Provence, Francia) y fundó una misa, que debe ser cantada a perpetuidad en honor de Santa María Magdalena.

Existen históricas de la existencia de un cáliz, propiedad del rey René de Anjou con una curiosa inscripción: “El que beba a fondo verá a Dios; el que la apure de un solo trago, verá a Dios y a la Magdalena.”

El Magdalen College de la Universidad de Oxford (Inglaterra) fue fundado en 1448, por William de Waynflete, obispo de Winchester, con el permiso del rey Henry VI de Inglaterra. Tiene una impresionante capilla del siglo XV. En él han estudiado: Oscar Wilde, Virgina Wolf, C. S Lewis

En 1599 un trabajador de una fábrica de papel en Frabiano (Italia) sufrió un accidente y quedó aplastado entre las bobinas de papel, pero invocó a La Magdalena y resultó ileso. La iglesia- s XIII- de dicho pueblo, era una capilla de un hospital dedicado a la Santa. Tras el milagro, la fábrica la adoptó como patrona.

Dice la leyenda que Myriam de Magdala trajo consigo desde Palestina, un puñado de tierra, y unas piedrecillas negras, manchadas con la sangre derramada por Jesucristo en la Cruz. Se guardan en San Maximino (Aix-en Provence) dentro de un frasco de cristal. Cada, Viernes Santo, se vuelven rojas y se licua la sangre. Este prodigio atrae en el siglo XVII a más de cinco mil personas.

El Metropolitan Museum de Nueva York, guarda un relicario de finales del XV, procedente de Florencia (Italia) que contiene un diente de la Santa.

Zwingli, (reformador iconoclasta suizo) pidió abolir el culto a María Magdalena y destruir todas sus imágenes, pues era un ejemplo de lo artificioso de la intercesión de los santos.

El Concilio de Trento (1545-1563) destaca la importancia de Santa María Magdalena como símbolo de la iglesia triunfante y de la fe verdadera.

San Isidro labrador, antes de comenzar su faena en el campo, acudía a orar en una capilla dedicada a La Magdalena, situada en lo que es hoy Carabanchel (Madrid).

Santa Teresa de Ávila (1515- 1582) relata en su obra Vida su gran devoción a la gloriosa Magdalena. Pedía su intercesión ante Cristo, para perdonarle sus pecados.

San Francisco de Sales (1567-1622) resaltaba a la Magdalena como ejemplo de conversión y amor.

En 1597 Bellarmino, teólogo del papa Clemente VIII compuso un himno donde relata las tres fases de la conversión de la Magdalena, titulado: Pater superni luminis. Está integrado en el breviario romano como parte del oficio de su festividad.

César de Nostredame, en 1606, le dedica un poema titulado” Les Perles ou Larmes de la Saincte Magdelaine” (Las perlas o lágrimas de Santa Maria Magdalena). Compuesto por 752 endecasílabos.

El jesuita inglés Robert Southwell (siglo XVI) le escribió dos poemas líricos titulados: “Marie Magdalens blush” (El rubor de María Magdalena) y “Marie Magdalens complaint at Christ death” (La queja de Maria Magdalena por la muerte de Cristo). Considerado uno de los poemas de amor más importantes de su época.

Bernardino Ochino, capuchino italiano, tras visitar la Sainte-Baume, pronunció un sermón en Venecia en 1539, donde resalta el papel de La Magdalena, como el máximo ejemplo de la iglesia militante.

En 1622 Luis XIII de Francia derrotó a los calvinistas en Languedoc. Terminó la guerra en Montpellier. Desde allí fue a dar gracias a La Magdalena de San Maximino (Provenza). Cinco años después, un 22 de julio, les atestó el golpe definitivo, en la batalla de La Rochelle al derrotar al ejército inglés capitaneado por el duque de Buckingham, que apoyaba a los calvinistas franceses.

El cuadro “La conversión de María Magdalena” de Gentileschi (1640) fue un encargo del gran duque Cosimo de Toscana como regalo a su esposa la archiduquesa María Magdalena de Austria, gran duquesa de Toscana. Hoy podemos verlo en la Galleria Palatina, del palacio Pitti, en Florencia (Italia).

En Antequera (Málaga) existe un convento de las franciscanas descalzas del siglo XVIII, dedicado a La Magdalena.

En 1816, Luis XVIII de Francia le dedicó la espectacular Iglesia Real de La Madeleine de Paris, fundada en el siglo XVI por Carlos VIII. Totalmente reconstruida por Napoleón Bonaparte en 1807.

En 1822- y ante 40.000 personas- fue reestablecido el culto a la Santa en la Sainte- Baume, paralizado durante la Revolución francesa de 1789.

En Inglaterra durante el siglo XIX se produjo un reverdecimiento del culto a la Santa. Existen varias iglesias famosas como la magistral iglesia neogótica de María Magdalena, en Paddington (1868-1878); otras más antiguas como la iglesia de Norfolk del S XIV, restaurada en 1873, cuyas vidrieras narran su vida. Otra pequeña iglesia medieval en Madehurst, West Sussex.; la iglesia All Saints, Langton Green, Kent y muchas más.

El zar de todas las Rusias, Alejandro III, en 1886, mandó construir una iglesia en su honor, como recuerdo a su madre, gran devota de la Santa. Dicha iglesia fue proyectada por De Graham.

Aguste Rodin recibe hacia el 15 de Diciembre de 1905 el encargo de August Thyssen de realizar una escultura sobre Jesucristo, por la que pagó 20.000 francos. Así creó “Cristo y La Magdalena” una escultura de mármol, único testimonio de inspiración religiosa del autor, tras dejar el noviciado de los Padres del Santísimo Sacramento. Hoy puede admirase en el Museo Thyssen – Bornemisza de Madrid.

En la Biblioteca Imperial de San Petersburgo (Rusia), el abate Joseph Bonnet descubre en el manuscrito Q I, 14 un sermón anónimo francés atribuido al teólogo, del siglo XVII, Bousset. titulado: “L ´Amour de Madeleine” (El Amor de Magdalena).En 1911 Rainer María Rilke lo adquiere en un anticuario de Paris, de la rue du Bac. Fascinado por el escrito, al que califica de “extraordinario, luminoso y de verdadera actualidad espiritual”, lo traduce.

En 1978 fueron suprimidos de la sección del Breviario romano dedicado a Santa María Magdalena, los epítetos: “María poenitens” (María penitente) y “magna pecatrix” (gran pecadora). Para terminar con dos mil años de estigmatización sobre su persona. Ahora sólo queda que el colectivo popular borre de su memoria la falsedad que durante siglos se cernió sobre la Santa.

En la iglesia del Monasterio de Oía (Pontevedra) del s. XIII hay un retablo donde hallamos la representación de la bajada del Espíritu Santo sobre la Magdalena, que está rodeada por los apóstoles

La imagen central del retablo de la capilla dedicada a San Juan Evangelista, del Monasterio cisterciense de la Santa Cruz (Santes Creuses) de Aiguamúrcia (Tarragona), podemos ver un cuadro representando a la Magdalena, con una copa o cáliz en su mano izquierda. Este monasterio pertenecía al Císter, orden fundada por San Bernardo de Claraval, cuya influencia en la creación de la Orden de los Caballeros Templarios, es notable.

Para algunos el “juego de la Oca” es la representación del Camino de Santiago; en este juego la casilla 58 es la muerte, que significa resurrección y por tanto correspondería a la Magdalena al haber sido la primera en ver a Jesús resucitado.

Hacia el 466-511 el rey merovingio Clodoveo adopta como emblema de su dinastía a la flor de lis. Símbolo que aún hoy representa a la Corona francesa y adorna la urna de cristal que contiene las reliquias de la Magdalena en la abadía benedictina de Vézelay, en Francia.

En 1929 se descubre en Dura Europos (Siria) un fresco con una representación de las primeras pinturas cristianas. Donde encontramos a La Magdalena con una antorcha encendida en la mano. Hoy esta pintura puede verse en la Galería de Arte de la universidad de Yale, en EE.UU.

San Agustín se refiere a La Magdalena como el “testigo ocular” de la resurrección de Jesús.

El número 7 está asociado con la Magdalena, recordemos el pasaje del evangelio según san Lucas “y también algunas mujeres que habían sido curadas de malos espíritus y enfermedades: María, llamada Magdalena, de la que habían salido siete demonios” (Lc 8,2). El siete está relacionado con la perfección del tiempo. Significa “perfección”, “importancia” o “plenitud”. Es el número perfecto ya que Dios al crear el mundo descansó el séptimo día. También asociado con el Espíritu Santo (los 7 dones del espíritu); o con Ishtar (7 velos); o los 7 pecados capitales, e incluso para algunos guarda relación con la virginidad, ya que no genera ni es generado por ninguno de los otros números de la primera decena. Pero además una curiosidad ¿Se han fijado en una cosa? La Hoguera se celebra el 21 de julio ¿verdad? Hagan estas operaciones 21/3=7. Y Julio es el séptimo mes del año. ¿Casualidad, o causalidad?

Hacia 1888 Vincent Van Gogh llega al pequeño pueblo pesquero de Saintes-Maries-de-la Mer donde la tradición ubica que desembarcó la Magdalena. Durante esa época Van Gogh realiza gran parte de su obra.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| San Bernardo de Claraval |

|

|

| Abad de Claraval |

| 1115-1128 |

|

| Otros títulos |

Doctor de la Iglesia

proclamado en 1830 por el papa Pío VIII |

| Información religiosa |

| Congregación |

Orden del Císter |

| Iglesia |

Iglesia católica |

| Culto público |

| Canonización |

18 de enero de 1174, por Alejandro III1 |

| Festividad |

20 de agosto |

| Atributos |

Báculo y libro |

| Venerado en |

Iglesia católica, Iglesia anglicana, Iglesia luterana |

| Patronazgo |

Gibraltar, Algeciras, San Bernardo del Viento, San Bernardo del Tuyú, Salta, apicultores |

| Santuario |

Catedral de Troyes, Troyes, Francia |

| Información personal |

| Nacimiento |

1090

Fontaine-lès-Dijon, Borgoña, |

| Fallecimiento |

20 de agosto de 1153 (63 años)

Abadía de Claraval, Ville-sous-la-Ferté |

| Padres |

Tescelin de Fontaine y Alèthe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jerusalén, era la sede de la Orden del Temple. Las casas de: Francia, España, Portugal, Italia e Inglaterra, siempre estuvieron ligadas a la Casa de Jerusalen y la existencia principal de las mismas, era aportar los Caballeros e Ingresos necesarios, para recuperar y mantener los Santos Lugares.La perdida de Jerusalén, tralado la Sede a Chipre, aunque la Casa de Paris, empezo a ejercer una influencia relevante, habida cuenta que el Papa, habia trasladado su residencia a Francia y la ORDEN, dependia directamente del Papa.En la Bula Omne datum optimum dirigida al maestre Robert de Craon se dice: Ninguna casa, excepto aquella en la que vuestra Orden se establecio en un principio, debe ser dueña y soberana |

|

|

|

|

The Nard of Mary-Magdalene

My fools for senses,

Today, we shall be looking for an answer centuries of commentors failed to provide. Following our Review of Irrévérent and its unusual accord of oud and lavender, we decided to ponder awhile on this last ingredient which we thought we knew too well. Most of all, we wanted to envision it with a new eye : that of theology. Of history and literature and cooking and anthropology.

For indeed lavender passed through many cultures and through many readings did we stumble upon a most startling fact : that nard and lavender, in the Bible, are one. Thus, my fools for senses, let us discover today what really hid behind the Nard of Mary-Magdalene.

All good adventure movies start with a writing on a wall or in a book in our case. In the Bible, really. “Mary, having taken an ounce of pure nard anointed with it the feet of Jesus” This moving scene will very lively raise more than one question in the reader's mind : whatever is nard and why use it to anoint the Christ's feet ?

To properly grasp what nard is or was, one must look at its history and all the times it was mentioned. As far as we can tell around the Mediteranean Sea, Dioscorides spoke of nard in De Materia Medica. Of more than one actually. He lists a Syrian nard, an Indian nard and a Celtic nard. According to him, the Syrian nard got its name from the fact that it grows on the western slope of a mountain range -he was probably referring to the Hindu Kush. He also says its sweet aroma is close to that of nard from Cyprus. Indian nard is apparently smoother and more watery considering it grows in the Gange basin. The Celtic nard at last is both sweet and suave. He also mentions a wild nard growing in the mountains known already by the Gauls. As for Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History he lists a numerous variety of nards and one in particular that was so sweet-smelling that it was a most sought-after oil.

Roman literature is also a good resource when it comes to perfumes. In his Odes –the tenth to be more precise- Horace speaks of an « Assyrique nardo », Assyrian nard, whereas Petronius in his Cena Trimalchionis has one of his characters open an « ampullam nardi », a phial of nard, which was then rubbed on al the guests’ noses. Knowing the musty, musky scent of nard, one might be surprised upon reading so many lauds to it and the Roman nobility anointing their noses with it as they end a banquet. However, there happens to be mentions of nard in the Apicius, a Roman cookbook, according to which a few drops of nard might be useful to freshen a stale broth.

This occurrence of nard in a cookbook really raised our eyebrows and convinced us that nard was in fact lavender but how did the Romans end up confusing both ?

One must go back to the origins. Nard was named after the Assyrian city of Nuhadra –in actual Iraq- sitting on the banks of the Tigris river. Probably known for trading precious oils, one might say it was the starting point of spikenard trading routes going west into the Roman Empire although the nard existed way before the Romans. Already is it seen in a recipe for the anointing oil of Parthian kings as well as in Arrian’s Anabasis in a curious tale where the soldiers, as they traverse the desert of Gadrosia, find themselves trampling a « grass of nard » which then exhaled a sweet-smelling aroma. Research has now shown that this so-called nard was in fact…lemongrass.

To establish a link between the freshness of lemongrass and that of lavender isn’t much of a stretch.

Moreover, we looked for answers into the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which has gone uninterrupted since the early years of our era. After having ordered many an incense and nard-scented oils, we realised they were in fact all perfumed with lavender. Thus, we wondered why Mary-Magdalene anointed Jesus’ feet with nard –or lavender.

For so, let us dive into the writings. In the famous passage, St John writes : « nardou pistikes », « pure nard ». Some translated it into « true nard » as opposed to the fake one being lavender however we still think that « pistikes » has nothing to do with botanics. The Peshitta, an Aramaic translation of the Gospels, wrote : « dnardeen reeshaya ». Reeshaya here means « the best », of great quality. The symbolical use of the word reeshaya is most clearly seen in the Gospel of St Mark where Mary-Magdalene breaks « of pure nard. » on Jesus’ « head ». The Peshitta writes : « dnardeen reeshaya (…) al reesheh dyeshoo » a play on the words « reeshaya » which we’d roughly translate to : she poured the best on the Best.

Why pouring nard, though ? Or rather lavender ?

It is now known that myrrh is a symbol for death. It would thus have been very clever of Mary-Magdalene to anoint Jesus’ feet with it as a sign of his upcoming death and burial but she chose lavender. As such, her anointement is nothing short of a prophecy, lending us precious informations on the secret symbolism hidden behind lavender.

We read how the Ancients confused nard with lavender but we must now explain why they did so for they spoke of spikenard and lavender spike. The first bore its name from the fact its root looked like it was spiking out of the stem. The latter bore its name from its resemblance to an ear of wheat and this is precisely where we need investigate for therein lies the key to understanding the real meaning of lavender and solve a millenial controversy.

When Mary Magdalene poured lavender spike on Jesus’ feet, she accomplished a prophetic gesture of which she had probably no knowledge –as most prophecies in the New Testament. Along with St John whose head lies on Jesus’ chest - announcing the theosis- and the Virgin Mary who looked westward as her baby lay in her arms –announcing the Passion- Mary Magdalene announces the Passion and Resurrection. For as she poured the best on the Best, it is precisely the oil of the best ear of wheat which she poured upon He who compared himself to a « kernel of wheat ». This gesture is a clear reference to the words of Jesus saying on the eve of his death : « Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds »

The anointing of Jesus’ feet in the Gospel of Saint John heralds that of the myrrh-bearers and his Resurrection and of the Holy Spirit as it shone on his head upon his descent in the Hades, to a crown of light inextinguishable alike.

What we must understand is that lavender is akin to the light which shrouded the Christ as he went down into the Hades. Furthermore, mediaeval traditions will swiftly associate lavender to the virtue of keeping evil and dark spirits at bay. Lavender is a twig of life, fortifying the heart of Men ; it is the scent we smell as we leave a heartwarming feast, saying « I only hope it will give me as much pleasure when I'm dead as it does now when I'm alive. » It the the flower of foreseers, of those who see beyond appearances and the simple planes of existence.

The flower of they who want to trample and have trampled down death. The flower of soldiers as they traverse the desert, the flower of queens and kings chasing away all sorrows and withering of the soul.

Even more so than frankincense, lavender and its hues of violets and blues, is the perfect flower to connect us to the ethereal worlds. It clings to our soul and lifts it up and says to all and to us foremost that Love, over death, has won.

Your goodness and nard will follow me,

All the days of my life.

https://www.theperfumechronicles.com/chronicles/nard |

|

|

|

|

Secrets of the Knights Templar

They’re shrouded in mystery and conspiracy theories. A history scholar unpacks their real story.

Just mention the Knights Templar and the conspiracy theories start flying. But just who were the medieval Knights of the Temple? What was their job and what happened to them? Why do they still capture our imaginations? The Knights of the Temple—the Templars, for short—were established in the early 1100s under a Rule written by Bernard of Clairvaux,a famous Cistercian abbot. He modified existing Rules for religious monastic communities to fill the need for an armed order in light of the Crusades. This Rule and the Templars’ lifestyle became the model for about a dozen other religious military orders in the Middle Ages.

There are versions of these orders today, some of which can trace their lineage directly back to medieval ancestors. Others have chosen to emulate the original orders but adapt them to our times. These contemporary communities, now often composed of men and women, have turned to massive charitable and philanthropic projects and to protecting endangered Christians. One example of an adapted version of the medieval Templars is the Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem. Other modern expressions of medieval orders are the Knights of Columbus, the Knights and Dames of Malta (who trace their lineage back to the Hospitallers of St. John), and the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre.

Let’s take a look at the history behind the legend of these highly influential knights. It is a tale of medieval palace intrigue worthy of a Hollywood movie, which doesn’t have to make things up to be true.

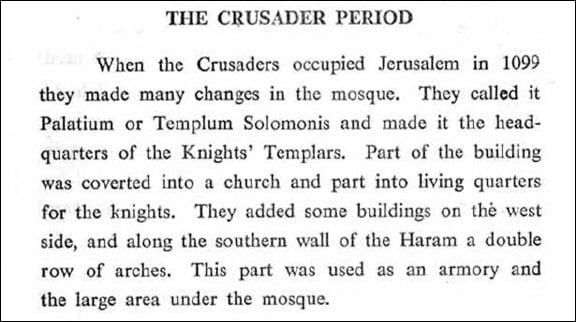

Monk-Warriors

The story starts at the time of the Crusades. In 1095, Pope Urban II called for European Christian knights to stop fighting each other and to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. The pope’s speech sent thousands of knights, infantrymen, and a large supporting workforce streaming across Europe, resulting in the taking of Jerusalem in 1099. But these were not unified armies under a tight leadership team. Many knights behaved shamefully and certainly did not live up to the standards of chivalry and charity—even toward fellow Christians. Clearly there was a need for order, control, and standards.

The Templars had their origins at just this point in time. At first, there were about 10 French knights with their retinues escorting pilgrims from the Mediterranean coast to the holy city of Jerusalem and other sites in the area, such as Bethlehem, Bethany, Nazareth, and the Jordan River. The Muslims quickly regrouped, however, and began to take land back in this same period. Their victories led to the Second Crusade (1147‚ 1149), which was promoted by that same Bernard of Clairvaux.

By this time, it was clear that in order for the European Christians to maintain their hold on Jerusalem and keep the passages to Jerusalem safe, a more organized and permanent military presence needed to be set up. Most of the knights from the First Crusade simply left Jerusalem after taking the city in 1099. That group of French escorting knights, then, became the seed for the Templars.

In his Rule for the order, In Praise of the New Knighthood, written in 1128, Bernard of Clairvaux called these fighting men “knights of Christ.” He envisioned them as monk-warriors. The Templars and other orders at first saw their task as fighting to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land, even if that meant taking up arms while still holding to the three traditional monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Later, it meant protecting the faith from internal threats caused by heretics, once again by violence, if necessary.

Bernard captured the paradox when he said that the knights must be “gentler than lambs, yet fiercer than lions. I do not know if it would be more appropriate to refer to them as monks or as soldiers, unless perhaps it would be better to recognize them as being both.” He described the model Templar as “truly a fearless knight and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armor of faith just as his body is protected by armor of steel.”

Bernard also drew on the just-war tradition to say that, in certain circumstances, Templar violence was permitted and not sinful. “If he fights for a good reason, ” Bernard wrote, “the issue of his fight can never be evil.” Elsewhere in his Rule for the Templars, Bernard stated, “To inflict death or to die for Christ is no sin, but rather, an abundant claim to glory.” So for the Templars, fighting the infidel (literally, “the unfaithful ones”) meant the Muslims in the Holy Land.

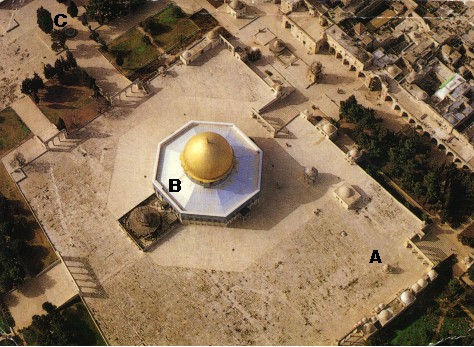

The World of the Templars

The Templars took their name from their headquarters, situated on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This is where Solomon’s Temple had stood from about 970 BC until it was destroyed in 587 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar, who took the Israelites back to Babylon and left Jerusalem a backwater. Centuries later, about 20 BC, the client-king of the Romans, Herod, began to rebuild the Temple, which has come to be known as Herod’s Temple, Jesus’ Temple, or the Second Temple. It was barely completed before it was destroyed by Roman imperial forces in AD 70. Over a thousand years later, the elite knights envisioned by Bernard established their command center in what some still called Solomon’s Temple or Palace.

At its height during the crusading centuries, the Knights of the Temple included about 300 knights who had taken the three standard vows. Many of these vowed knights were in their 20s when they joined. They were supposed to be unmarried, free of debt, and of legitimate birth. They wore a distinctive tunic and wielded shields painted white with a prominent red cross.

The knights were joined by as many as 900 soldiers who were not noble and fought on foot—an infantry to complement the knights’ cavalry.

There would have been hundreds of others, which we would call support staff, employed by the order: blacksmiths, squires, women to cook and take care of clothing, and armorers. Some of the men among this support staff were like lay brothers in other religious orders, such as the Benedictines or Cistercians.

The Templars, like medieval monasteries and convents, were run very collaboratively. They held property and goods in common, making decisions about them and all other matters by vote. They were led by a grand master chosen by the vowed knights in an election.

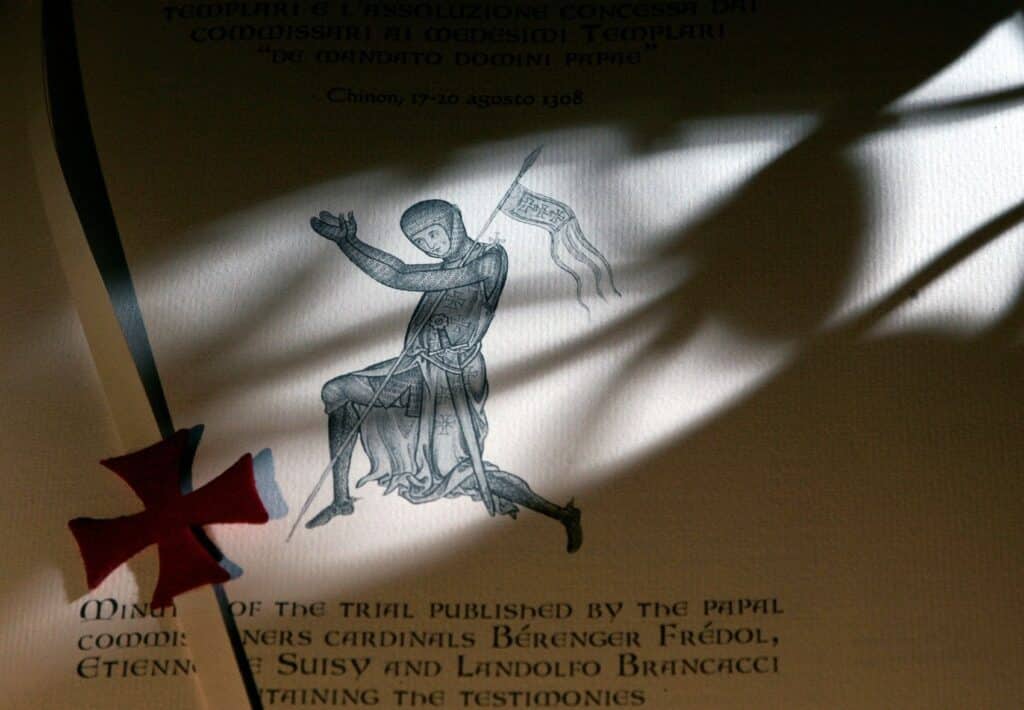

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

At the same time, however, elements of Templar life drew attention and led to rumors about them. They reported directly to the pope. They were also exempt from paying taxes, which increasingly became a big deal as they amassed huge areas of land. The Templars also attracted patrons quickly and in large numbers across western Europe.

They eventually enjoyed a network of nearly 2,000 castles, houses, and estates. (A modern-day analogy might be America’s super-wealthy robber baron families who built huge mansions they called cottages in the days before income tax.) We can see the mysteries that persist today started early.

Behind Closed Doors

Above all, the Templars held all of their deliberations and votes in secrecy. When they were fighting the infidel and protecting pilgrims, this was not an issue. But when the Crusades ran their course and Muslims systematically took back Holy Land territory and negotiated treaties for safe passage for Christian pilgrims, the Templars began to lose their reason for being there. When Muslims took Acre in 1291, Holy Land crusading effectively ended—leading to the next and final chapter for the Templars.

With no need to fight in the Holy Land, the Templars largely turned from military affairs to the worlds of finance, estate management, trade, banking, and overseeing investments along their network of tax-exemptproperties in Europe. They were likely the richest operation in the Middle Ages, essentially making them Europe’s ATM.

They were not without enemies, and their worst one was Philip IV, king of France. He is also known to history as Philip the Fair (le Bel), who reigned from 1285 to 1314. He had been trying to control the papacy and Church in France for some time by taxing the clergy without papal permission.

Effectively, he was trying to separate Catholic France from papal authority (later known as Gallicanism). Philiphad particularly tangled with a stubborn pope named Boniface VIII (1294‚ 1303). The king had even sent armed men to intimidate Boniface because the pope planned to excommunicate him. Boniface died shortly after this verbal assault and physical threat, perhaps as a result of the shock of the ugly episode.

Philip continued to pressure the papacy, this time in the person of the weak Pope Clement V (1305–1314), the first of the line of 14th-century popes who resided in Avignon and not Rome. This royalty-versus-papacy fightimp acted the Templars because Philip was in a towering pile of debt to the military order. Trying to get out of repaying, the French king accused the Templars of losing the Holy Land and not living up to their own high standards. Now he had the pope as a powerful tool to attack the Templars.

To take them down, Philip exploited the mystery behind the Templar practice of secrecy. He accused them of black magic, sodomy, and desecration of the cross and Eucharist. The French king engineered an overnight mass arrest of Templars in October 1307. Over the next four years, nearly all Templars were exonerated at trials held across Europe with the notable exception of France. There, after being tortured, some Templars confessed to doing things like spitting on the cross or denying Jesus during secret initiation rites. Many later took those confessions back, saying they had admitted such things only under pain and fear of death.

The End of an Era

The final act took place at the general Church council held at Vienne from 1311 to 1312. Philip was in charge and made sure only bishops supporting him and not Pope Clement were present, to the point of knocking the names of anti-royal bishops off the list of those invited. Even under pressure from the French king, the bishops still voted in a large majority against abolishing the Templars and said the charges against them were not proven.

Philip played his hand by threatening violence against a pope once again. He pressured Clement to condemn his papal predecessor Boniface as a heretic. What the French king really wanted was to get out of debt to the Templars and seize their assets. Pope Clement allowed the Templars to be railroaded by trading off that threat against Boniface, which would endanger his own position as a papal successor. Clement went against his bishops and suppressed the Knights of the Temple on his own papal authority. Quite simply, the pope had been bullied by the king and he gave in. Clement praised “our dear son in Christ, Philip, the illustrious king of France,” adding remarkably, “He was not moved by greed. He had no intention of claiming or appropriating for himself anything from the Templars’ property.”

But instead of handing their money and property over to Philip, as the king wanted, the pope showed some courage and assigned the Templar assets over to the Knights of the Hospital (the Hospitallers). Philip got his cut, of course, and was out of debt to an order that no longer existed, but he didn’t win entirely. Pope Clement never said whether or not the Templars were guilty of heresy or other crimes.

In fact, in 2001, Vatican researcher Barbara Frale discovered in the archives there a misfiled document that has come to be called the Chinon Parchment. This collection details trial and investigation records in Latin from 1307 to 1312. A measure of the continuing interest in the Templars may be found in the fact that a limited reproduction edition of the Chinon Parchment was produced in 2007. Titled Processus Contra Templarios (“Trial against the Templars”), each of the 799 copies cost over $8,000. The 800th copy was given for free to Pope Benedict XVI.

The Chinon Parchment proves that Pope Clement definitely believed in 1308 that the charge of heresy against the Templars was not true, although they were guilty of other, smaller crimes. But Clement just wasn’t strong enough to protect the Templars from annihilation. Finally, in 1314, the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay was burned at the stake as a lapsed heretic after he retracted his tortured confession and asserted his innocence. The history of the Templars had come to an end, but its reputation for secrecy and all of this palace intrigue seemed destined to make the myths about them continue to live on.

Sidebar: Conspiracies and the Templars

Because of their secrecy and power, the Templars have refused to die—in myth if not in fact. In part because people want to believe nearly anything about the Church (witness the legend of Pope Joan), the Templars are ripe for exploitation. Spend 10 minutes searching the Internet with the words Templars and conspiracy.

The Templars show up as mysterious and shadowy figures in Hollywood movies like The Da Vinci Code, where they are linked with the Priory of Sion as guardians of Jesus’ alleged descendants with Mary Magdalene. Take nearly any mysterious group or object and the Templars are linked by innuendo and rumor: the Temple Mount, the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Grail, the True Cross, the Shroud of Turin, and the Freemasons. One legend says they magically appeared to turn the tide of a battle in Scotland. Another claims they crossed the Atlantic Ocean before Columbus. Some of the wilder stories tie the Templars to President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and even Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation in 2013—and that’s before we get to the video games and The Templar Code for Dummies.

Perhaps all of this spookiness can be brought back to their end. It happened that the Templars were rounded up on Friday the 13th of October, 1307, which some people claim is the root of that feared calendar date. Moreover, as he went to his death at the stake, Grand Master Jacques de Molay supposedly issued a curse that he would meet PopeClement and King Philip with God within a year—and indeed both pope and king died shortly after.

https://www.franciscanmedia.org/st-anthony-messenger/secrets-of-the-knights-templar/ |

|

|

|

|

Bernard of Clairvaux

Above: Bernard of Clairvaux

by Alan Butler

Born Fontaine de Dijon France 1090

Died Clairvaux, near Troyes, Champagne France August 20th 1153

Bernard of Clairvaux may well represent the most important figure in Templarism. In our opinion past researchers have generally failed to credit St Bernard with the pivotal role he played in the planning, formation and promotion of the infant Templar Order. Whether an ‘intention’ to create an Order of the Templar sort existed prior to the life of St Bernard himself is a matter open to debate. (See ‘The Templar Continuum’ Butler and Dafoe, Templar Books 2,000).

The son of Tocellyn de Sorrell, Bernard was born into a middle-ranking aristocratic family, which held sway over an important region of Burgundy, though with close contacts to the region of Champagne. There is some dispute as to whether Bernard’s father had fought in the storming of Jerusalem in 1099, and indeed whether he died in the Levant. The question appears to be easily answered for in the small Templar type Church in St Bernard’s birthplace there is a marble plaque that states the Church was built by St Bernard’s mother in thanks for the safe return of her husband from the Crusade.

St Bernard was a younger member of an extremely large family. He appears to have received a good, standard education, at Chatillon-sur-Seine, which fitted him, most probably, for a life in the Church, which, of course, is exactly the direction he eventually took. Many stories exist regarding Bernard’s early years – his visions, torments and realisations. All of these were attributed to Bernard after his canonisation and therefore must surely be taken with a pinch of salt. What does seem evident is that Bernard was bright, inquisitive and probably tinged with a sort of genius. Certainly he was a fantastic organiser and possessed a charisma that few could deny.

St Bernard enters history in an indisputable sense at the age of 23 years, when together with a very large group of his brothers, cousins and maybe other kin, (probably between 25 and 30) he rode into the abbey of Citeaux, Dijon. This abbey was the first Cistercian monastery and had been set up somewhat earlier by a small band of dissident monks from Molesmes. Much can be found elsewhere in these pages relating specifically to the Cistercians. At the time of St Bernard’s arrival the abbey was under the guiding hand of Stephen, later St Stephen Harding, an Englishman.

Bernard announced his determination to follow the Cistercian way of life and together with his entourage he swamped the small abbey, swelling the number of brothers there to such an extent that it was inevitable that more abbeys would have to be formed.

Only three years later St Bernard, still an extremely young man, (25 years) was dispatched, together with a small band of monks, to a site at Clairvaux, near Troyes, in Champagne, there to become Abbott of his own establishment. It is known that the land upon which Clairvaux was built was donated by the Count of Champagne, based at the nearby city of Troyes.

St Bernard was a visionary, a man of apparently tremendous religious conviction. He could be irascible and domineering at times, but seems to have been generally venerated and well liked by those around him. Bernard suffered frequent bouts of ill health, almost from the moment he joined the Cistercians. This continued for the remainder of his life and may have demonstrated an inability on the part of his digestive system to cope with the severe diet enjoyed or rather endured by the Cistercians at the time.

Bernard’s influence grew within the established Church of his day. With a mixture of simple, religious zeal and some extremely important family connections, this little man involved himself in the general running, not only of the Cistercian Order, but the Roman Church of his day. Bernard was instrumental in the appointment of GREGORIO PAPARESCHI, Pope Innocent II in the year 1130, despite the fact that not all agencies supported the man for the Papal throne. Bernard walked hundreds of miles and talked to a great number of influential people in order to ensure Innocent’s ultimate acceptance. His success in this endeavour marked St Bernard as probably the most powerful man in Christendom, for as ‘Pope Maker’ he probably had more influence than the Pontiff himself.

This appointment should not be underestimated, for it was Pope Innocent II who formally accepted ‘The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon’ (The Knights Templar) into the Catholic fold. This he did, almost certainly, at the behest of Bernard and possibly as a result of promises he had made to this end at the time Bernard showed him the support which led to the Vatican.

To understand St Bernard’s importance to Cistercianism it is first necessary to study the Order in detail. In brief however it would be fair to suggest that Bernard’s own personality, drive and influence saw the Cistercians growing from a slightly quirky fringe monastic institution to being arguably the most significant component of Christian monasticism that the Middle Ages ever knew.

In addition to this St Bernard consorted with Princes, Kings and Pontiffs, even directly ‘creating’ his own Pope, BERNARDO PAGANELLI DI MONTEMAGNO (Eugnius III) who became Pontiff in 1145. This man had been a noviciate of St Bernard at Clairvaux and was, in all respects, St Bernard’s own man. From this point barely a decision was made in Rome that was not influenced in some way by St Bernard himself.

Much could be written about the ‘nature’ of St Bernard. He was a staunch supporter of the Virgin Mary, a visionary and a man who had a profound belief in an early and very ‘Culdean’ form of Christianity. This is exemplified by the short verse he once wrote.

‘Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.’

St Bernard staunchly supported what amounted to an utter veneration of the Virgin Mary for the whole of his life and was also an enthusiastic supporter of a rather strange little extract from the Old Testament, entitled ‘Solomon’s Song of Songs’.

How and why St Bernard became involved in the formation of the Knights Templar may never be fully understood. There is no doubt that he was blood-tied to some of the first Templar Knights, in particular Andre de Montbard, who was his maternal uncle. He may also have been related to the Counts of Champagne, who themselves appear to have been pivotal in the formation of the Templar Order.

For whatever reason St Bernard wrote the first ‘rules’ of the Templar Order. He may have undertaken this task personally and they were based, almost entirely, on the Order adopted by the Cistercians themselves. The Templars were officially declared to be a monastic order under the protection of Church in Troyes in 1139. Bernard went further and insisted that Pope Innocent II recognised this infant order as being solely under the authority of the Pope and no other temporal or ecclesiastical authority. It is a fact that the Templars venerated St Bernard from that moment on, until their own demise in 1307. St Bernard’s influence on the Templars is therefore pivotal to the whole of the movement’s aims and objectives and in our opinion no researcher should ever underestimate Bernard’s importance with this regard.

St Bernard travelled extensively, negotiated in civil disturbances and, surprisingly for the period, was instrumental in preventing a number of pogroms taking place against Jews in various locations within what is present day France. A staunch supporter of an Augustinian view of the mystery of the Christian faith, St Bernard was fiercely opposed to ‘rationalistic’ views of Christianity. In particular he was a staunch opponent of the dialectician ‘Peter Abelard’, a man whom St Bernard virtually destroyed when Abelard refused to accept Bernard’s own criticism of his radical ideas.

Although travelling extensively on many and varied errands during his life, St Bernard always returned to his own abbey of Clairvaux, which it seems (to us at least) had been deliberately built in a location that allowed free travel in all directions. It is suggested that Clairvaux was peopled with all manner of scholars, some of whom may well have been Jewish scribes. It is also true to say that if Citeaux remained the ‘head’ of the Cistercian movement during the life of St Bernard, Clairvaux lay at its heart. Clairvaux became the Mother House of many new Cistercian monasteries, not least of all Fountaines Abbey in Yorkshire, England, which itself was to rise to the rank of most prosperous abbey on English soil.

St Bernard died in Clairvaux on August 20th 1153, a date that would soon become his feast day, for St Bernard was canonised within a few short years of his death. Space here does not permit a full handling of this extraordinary man’s life or his interest in so many subjects, including architecture, music and (probably) ancient manuscripts. After his death a cult of St Bernard rapidly developed. At the time of the French Revolution St Bernard’s skull was taken for safekeeping to Switzerland, eventually finding its way back to Troyes. It is now housed in the Treasury of Troyes Cathedral and can be seen there, together with the skull and thighbone of St Malachy, a friend and contemporary of St Bernard.

A much fuller and more comprehensive detailed biography of St Bernard’s life can be found in ‘The Knights Templar Revealed’ Butler and Dafoe, Constable and Robinson – 2006.

About Us

TemplarHistory.com was started in the fall of 1997 by Stephen Dafoe, a Canadian author who has written several books on the Templars and related subjects.

Read more from our Templar History Archives – Templar History

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

14 a 28 de 28

Siguiente Anterior

14 a 28 de 28

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/NYOFE4SO2JCGHF6IIT6EMBXGXI.jpg)

Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes.

Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes.

![Amazon.com: Angels & Demons [DVD] : Películas y TV](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/91e--fCvC-L._SL1500_.jpg)