Stylistic and architectural similarities between the cave of Machpelah enclosure at Hebron and the Temple Mount enclosure in Jerusalem have been clearly demonstrated by Nancy Miller in “Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years.”

I would like to suggest another similarity between the two sites at Hebron and Jerusalem. Originally, in the Middle Bronze Age, both were cemeteries. Does it seem strange that a temple—the dwelling place of God on earth—should be built in the midst of a cemetery? Let us look at the evidence.

Before turning to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, however, let us first review the situation in Hebron at the cave of Machpelah.

Nancy Miller described two different caves connected by a corridor beneath the enclosure. But the reports of a number of other openings in the area buttress the contention that here was not simply a burial cave or two, but an extensive burial ground. At least four entrances to caves inside the enclosure and its immediate surroundings have been reported, although there is no accurate documentation of these entrances; nor is it clear where they led. Two of the entrances have been known at least since the Crusader period. Another opening was reported in the Early Islamic period. Also supporting the existence of a whole cemetery here and not just a couple of burial caves is the deeply rooted Jewish tradition that kept adding important personages to the list of those buried at Machpelah—not only the patriarchs and their wives, but Joseph, Jacob’s other sons, Adam and Eve, even Moses and his wife Zipporah. As suggested in a Jewish mystical text, the Zohar, the souls of all the righteous pass through Machpelah on the way to Paradise, which, according to this account, is located adjacent to the burial ground. These stories are, of course, legendary, but they do reflect a knowledge, or perhaps it would be more accurate to say a historical memory, that the Machpelah area was once a large burial ground.

Turning from legend to later explorers’ reports, we find that the Italian explorer Pierotti reported an opening, or perhaps several openings, to a subterranean area below the Jawaliyeh mosque adjacent to the cave of Machpelah on the northeast.1 Colonel Meinertzhagen, an intelligence officer under General Allenby, entered the cave of Machpelah while on duty in 1917.2 Meinertzhagen entered an open stone doorway near the tombstone of Abraham, which may have been still another opening. Nothing further is known of this opening. Repair and restoration work in the garden in front of the southwestern facade of the enclosure revealed a circular cave 26 feet in diameter and about 15 feet high. The floor of this cave was nearly 50 feet below the rock surface. Since the floor is so far below ground level, the cave must have been entered through a vertical shaft. A similar cave was found just west of this one. Both caves had been used since the Roman period as water cisterns.3 Several other caves have also been excavated in front of the southwestern wall of the cave of the Machpelah enclosure.4

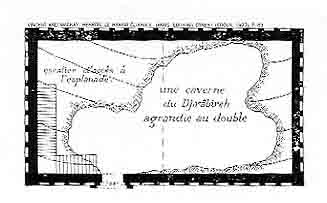

The traditional reconstruction of the cave of Machpelah beneath the enclosure is as a single large cave to which all the openings lead.5 This now seems wrong. All of these reported openings were likely to have been shafts leading to separate burial caves within the cemetery complex.

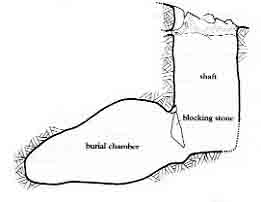

From the period archaeologists call Middle Bronze Age I or MB I (2200–200 B.C.), many cemeteries have been found in the Hebron mountains, southeast and northwest of Hebron.6 These cemeteries contain tens and often hundreds of tombs. The typical tomb is a small burial cave, often with a vaulted ceiling, entered from the surface above by means of a vertical shaft. The depth of the shaft varies, depending on the hardness of the local rock.

Like the Hebron mountain cemeteries, Machpelah too may originally have been a cemetery from the MB I period, containing many small burial caves entered by shafts. The many openings to subterranean chambers found in and around the Machpelah enclosure may well be the remains of these shafts. Once cut, these shaft tombs were no doubt used and reused for centuries, as was the practice in other cemeteries.7 Eventually some were used for cisterns. We will not speculate as to when Abraham purchased the cave described in the Bible, but it is worth nothing that the Biblical text is quite explicit in referring to the cave Abraham was offered by the Hittites as one of a group of burial caves: “Bury your dead in the choicest of our burial places” (Genesis 23:6).

We are not at all surprised that Machpelah was originally a cemetery, since it apparently retained its original function over the years. Eventually, it was hallowed as a national mausoleum of Israel.

The case of the Temple Mount in Jerusalem is quite different. King David purchased the site from Araunah the Jebusite (2 Samuel 24:18–25). Moreover, it was originally a threshing floor, an agricultural installation, before King David built an altar on the site, which thereby consecrated it. Thereafter, King Solomon built his temple to the Lord on this site. The site became the earthly base of Jewish worship and the ultimate source of ritual cleanliness.

Surely it is difficult to suppose that such a site was ever a cemetery. And yet some hints suggest that the earliest use of the site may have been quite similar to that of the cave of Machpelah; the Temple Mount may have been a cemetery at the end of the third millennium B.C.

These hints or clues come both from the site itself and from traditions about the site.

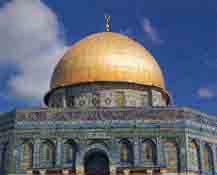

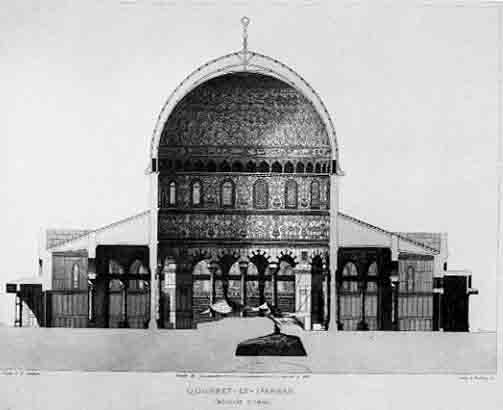

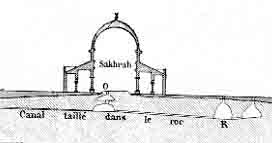

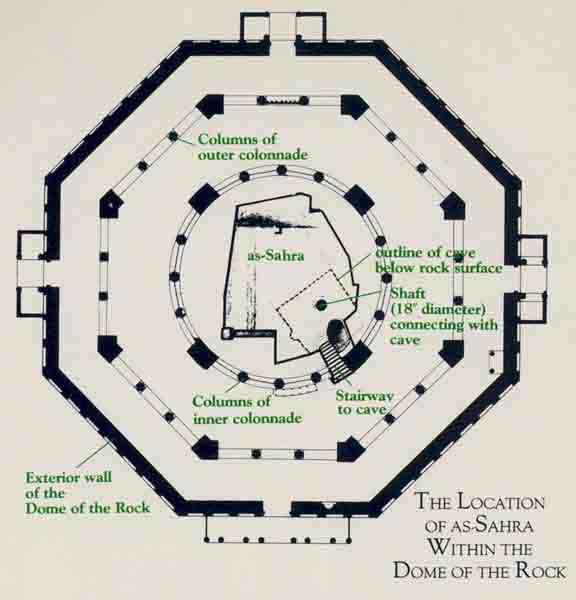

Let us look first at the most famous natural feature at the site, a large rock that is now magnificently enclosed by the Dome of the Rock. Varying opinions locate either the Holy of Holies of Solomon’s Temple or the great altar of sacrifice at this spot.8 Others suggest that the rock was part of King Solomon’s palace, which was also located on the Temple Mount.9 The majority of scholars, however, associate the rock with the Temple. We are concerned not with the rock itself, however, but with the cave under the rock.

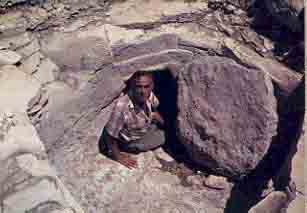

Today this cave is entered from the south by a stairway of 14 steps. The cave itself is almost rectangular, measuring 24 feet long by 23 feet wide. The ceiling is from just less than 7 to more than 8 ½ feet above the irregular natural rock floor.

In this rock floor is a depression covered by a marble slab. A dull sound is produced when this slab is tapped. This sound has been the source of both speculation and legends. The Moslems call this depression The Well of Souls; it is here that the souls of people heading for hell are stored. The image is strangely cemetery-like.

During the 19th century, speculation arose that a tunnel leading to the Kidron Valley began here, a kind of Temple escape route. In the early 20th century, Montague B. Parker, the leader of the famous Parker mission, smuggled himself into the Dome of the Rock at night to investigate the depression.10 His nocturnal expedition was discovered, and that ended his mission in Jerusalem. He barely escaped with his life. But during his nighttime visit Parker was able to remove the marble slab from the depression. What he found was that the depression was quite modest, less than 8 inches deep.

More significant than the depression in the cave floor is a round shaft 18 inches in diameter that perforates the rock ceiling of the cave and connects the cave with the rock surface. Could this be a remnant of an MB I shaft tomb?

The present configuration of the rock and the cave dates from the Crusader period, when the Dome of the Rock was converted into the Templum Domini Church (The Church of the Temple of Our Lord). Frankish Crusaders quarried stone chips from the sacred rock and sold them as souvenirs to pilgrims. To prevent this, one of the Crusader kings ordered the rock paved over with marble.11 (This paving was later removed by Saladin, the Moslem conqueror of Jerusalem.) Steps leading down to the cave were carved as early as the tenth century A.D. The Crusaders used the cave as a place of confession. They gave it its rectangular shape, repaired the stairway and crowned it with an ornate gateway. Charles Clermont-Ganneau, the 19th-century scholar-diplomat-explorer, investigated signs of chiseling on the western side of the stairway and found evidence of the use of medieval tools.12 So we cannot conclude anything from the present shape or condition of the cave.

I have already referred to the fact that the Moslems call the depression in the floor of the cave The Well of Souls. In 1173 A.D. a Moslem pilgrim named Ali el Herat refers to the cave as the Cave of the Spirits. He also tells of a tradition that the prophet Zechariah13 is buried here! In short, according to Moslem tradition, there was a burial, and perhaps burials, at the site; hence, the name; “Cave of the Spirits.”

There are similar hints in Jewish tradition. The Talmud records that a cave under the Temple was used as a genizah, a burial place for holy objects. (Palestinian Talmud, Shekalim 29a.)

Another talmudic story recounts how the exiles who returned from Babylon found the skull of Araunah under the Temple altar when they were reconstructing the Second Temple (Palestinian Talmud, Sotah 20a; Nedarim 39b). Apparently, a burial had been found and attributed to Araunah the Jebusite, one of only two pre-Israelite Jerusalemites known by name.

According to this account, the priests could not decide whether the skull defiled the Temple and therefore consulted the prophet Haggai. Haggai rebuked them, apparently because he could not answer them; the existence of a skull in such a sacred site was indeed strange and disturbing. The Talmud does not tell us what happened with the skull or with the altar, but it does reflect the persistent connection in Jewish tradition of the Temple Mount with a burial site.

According to still another talmudic account, the skull of Araunah had been found even earlier—by the high priest Hilkiah, who was responsible for the upkeep of the Temple during King Josiah’s (or King Hezekiah’s) reign (Palestinian Talmud, Pesahim 36b). Regardless of when it was discovered, the site had been used for a burial, according to this talmudic passage, before the Temple was built there.

All these references to finding the skull of Araunah are attributed in the Talmud to Rabbi Simon ben Zavdi, a sage of the third generation of Amoraim (sages of the Talmud), who lived between 290 and 320 A.D.14 The time of the event related in the various versions of the story is, as we have seen, the beginning of the Second Temple period or even earlier, in the First Temple period. We do not know how this tradition reached Rabbi Simon ben Zavdi.

Other hints in the sayings of the sages connect the site of the Temple with a burial site. In one source, it is said that “He who is buried in the Land of Israel is as if he were buried under the altar [of the Temple] … And he who is buried under the altar is as if he were buried under the throne of the Divine Majesty” (The Sayings of the Fathers According to Rabbi Nathan 26:8; Tosephta Abodah Zarah 4:3). The great talmudist Saul Lieberman expressed astonishment at this saying, because “to bury under the altar means to commit sacrilege, for it would defile the sacrifices offered on it.”15 Another tradition tells that the ashes of the ram that was sacrificed in Isaac’s stead were placed in the foundation of the altar16—another cemetery use of the site.

It would seem that the aggregate weight of all these traditions reflects some memories of a burial cave under the Temple.

Perhaps the knowledge that there had been a cemetery under the Temple site required that there be, in the words of the Talmud, “beneath both the Temple Mount and the courts of the Temple a hollowed space for fear of any grave down to the depth” (Mishnah, Parah 3:3). This would avoid the desecration of the sacred site by the dead buried below. Knowledge of the pre-existing cemetery is thus expressed indirectly, in terms of the need to protect the ritual cleanliness of the Temple Mount.

The substructure of arches upon arches, part of which is now known as Solomon’s Stables, was perhaps also meant to neutralize the effect of any possible tomb under the enclosure and divert its harmful effects to the Kidron Valley.

The whole question of a cemetery under the Temple Mount was veiled, however. Any open discussion of its possible existence would have cast serious doubt on the efficacy of the Temple as the ultimate source of ritual cleanliness.

As stated earlier, both the shape of the rock and the configuration of the cave under it underwent many changes, especially in the Crusader period. Apparently, the only feature that has remained more or less intact is the circular shaft that pierces the ceiling of the cave. Its round shape, its diameter (about 18 inches), and its careful workmanship are all typical of MB I tomb shafts leading to burial caves.

Is it possible that the cave under the rock was originally an ancient MB I tomb, thought by later generations to be the resting place of important personalities in the history of Jerusalem Araunah the Jebusite and, as Islamic tradition relates, the prophet Zechariah and the souls of the dead in general?17

Another interesting datum is the distribution of MB I cemeteries in the mountains of Hebron, Judea and Samaria. They are all located on or near the watershed line, the mountainous spine that runs through central Israel from Hebron to Bethlehem, Jerusalem, Bethel, Shiloh and Shechem. MB I cemeteries have been surveyed and excavated at Hirbet el-Kirmil southeast of Hebron, on Jebel Qa’aqir west of Hebron, in Hebron itself (if we accept the suggestion that Machpelah was originally an MB I cemetery), at Efrat and El’azar halfway between Hebron and Bethlehem, at Gibeon and Bethel north of Jerusalem and at ‘Ain es-Smiyeh in southeastern Samaria.18 Some of these cemeteries are huge, with hundreds of tombs, such as the one at ‘Ain es-Smiyeh; others are small, like the cemetery at Efrat, which has only 31 burial caves.19 When we study a map showing their distribution we find a lacuna, an empty hole in the map, in the Jerusalem area.

Jerusalem and its surroundings have been studied and excavated intensively during the last hundred years, but no sizable MB I cemetery has been found in the entire region, with the exception of one tomb on the Jerusalem-Jericho road20 and 11 tombs near the summit of the Mount of Olives.21 On the other hand, pottery sherds probably belonging to the end of the MB I period have been found in the City of David area south of the Temple Mount.22 These sherds did not come from burial caves but rather from the rock surface, and thus probably belonged to a small impoverished MB I settlement. Several such MB I settlements have recently been found in various parts of the country.23

It would seem that the burial ground of this MB I settlement in Jerusalem may have been located further up the hill from the area known as the City of David, in the area known today as the Temple Mount.

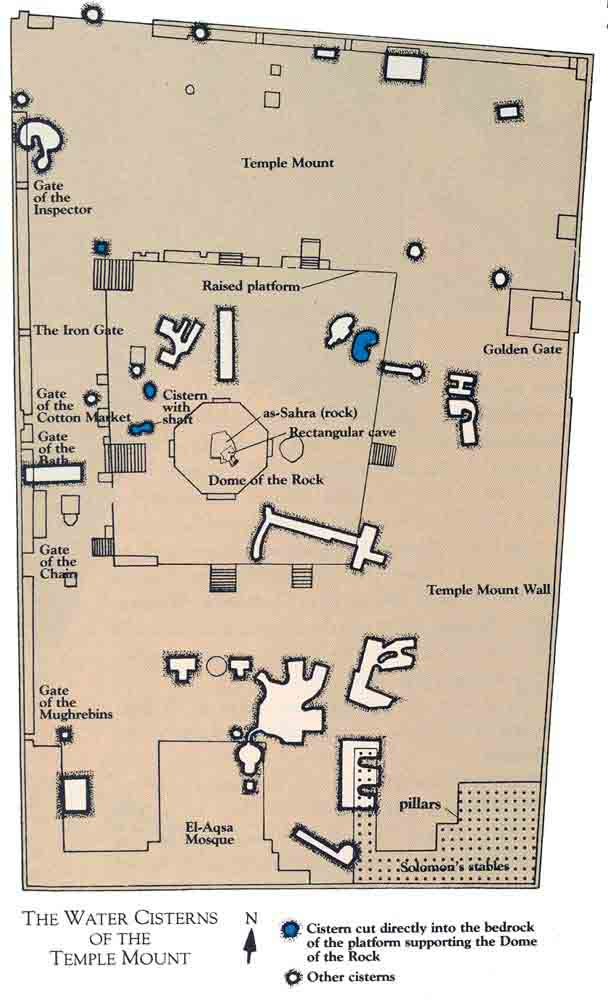

As is well-known, the entire area of the Temple Mount enclosure is perforated by numerous water cisterns, some dug into the fill under the enclosure, others cut into the rock foundation. Perhaps the rock-cut cisterns were originally burial caves. In some, the vertical entrance shaft has even been preserved.24

When the function of the Temple Mount area changed from a cemetery, so did the function of these ancient burial caves; they became water cisterns.

The series of chambers cut into the rock at the foot of the western wall of the Temple Mount enclosure and recently exposed in excavations25 may also have been part of this cemetery. The chambers, too, changed their function and shape, some serving for burial in the First Temple period, others being converted into ritual bathing installations (miqvaot) in the Second Temple period.

Thus, it would seem that the Temple Mount area and its immediate vicinity, in about the year 2000 B.C., was the site of the cemetery of a small settlement that would later be called Jerusalem.

It is interesting that at MB I Efrat, a similar topographic relation between settlement and cemetery was noted. The cemetery was located on a high, rocky slope; the settlement was built lower down.26 In Jerusalem, the cemetery was located on the high ground of the Temple Mount area, while the settlement was located lower down in the City of David area.

Some of the MB I burial caves in the Jerusalem cemetery may have been reused during Middle Bronze II (7000–1550 B.C.), a possibility suggested by the MB II pottery sherds found in depressions in the rock surface near the above-mentioned burial caves discovered west of the Temple Mount.27 Pottery sherds from this period were concentrated only in this location and not elsewhere in the extensively excavated areas west and south of the Temple Mount, indicating that the cemetery was here. The MB II settlement, on the other hand, was undoubtedly located, like the MB I settlement, in the City of David area; its city walls are currently being exposed on the eastern slope of the City of David, facing the Kidron Valley.28 A segment of this same wall had already been identified by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1960s.29 The reuse of MB I burial caves in MB II was noted at Hirbet el-Kirmil, Efrat and ‘Ain es-Smiyeh,30 so it would not be surprising if this also occurred at Jerusalem. The cemeteries at Hirbet el-Kirmil, Efrat and ‘Ain es-Samiyeh were not used again in later periods. This seems also to have been the case in Jerusalem—at least they were not used for burials.

At some point, this cemetery site, on the summit of what is now the Temple Mount enclosure, became a threshing floor owned by Araunah the Jebusite,31 and then it became a holy site. Only the slightest hints of its earliest use have survived the ages.

Sometimes there is no accounting for the twists of history: The MB I cemetery in Hebron retained its character as a cemetery for more than 4,000 years. In Jerusalem, the MB I cemetery became the site of Solomon’s Temple.