|

Réponse |

Message 1 de 30 de ce thème |

|

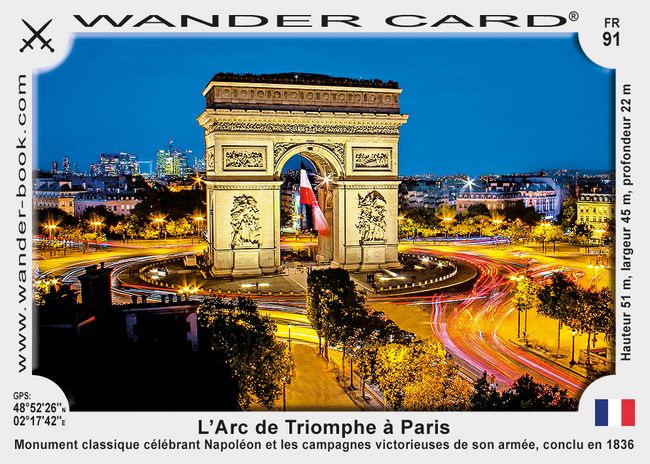

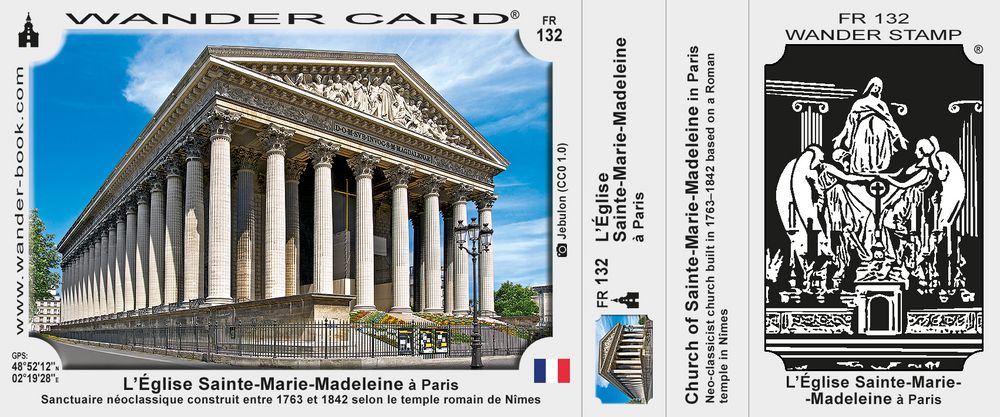

HD photographs of Saint Bernard statue on Eglise de la Madeleine in Paris - Page 1029

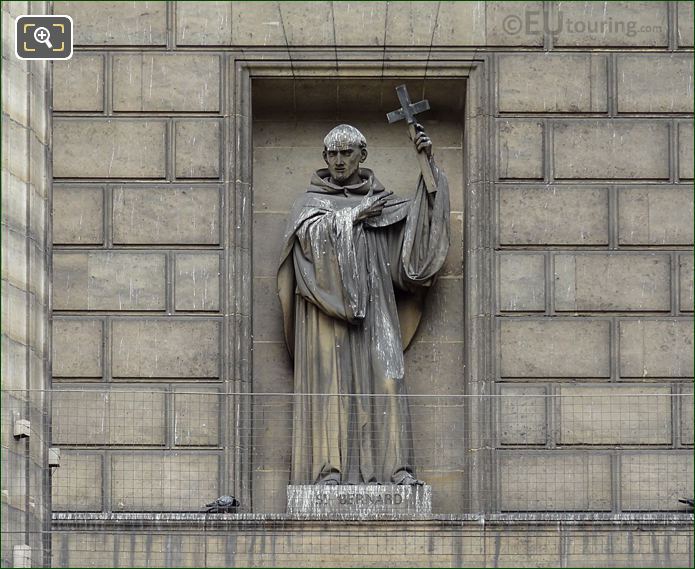

We were in the 8th Arrondissement of Paris at the Eglise de la Madeleine, when we took these high definition photos showing a statue depicting Saint Bernard, which was sculpted by Honore Husson.

Paris Statues

- << Previous 1021 1022 1023 1024 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 Next >>

This first HD photo shows one of thirty-four different saints that are located on the facades of the Madeleine Church, with this one depicting Saint Bernard, which was instigated by the architect Jacques Marie Huve and commissioned by the French state, it was produced in stone back in 1837 while the edifice was still under construction.

Yet here you can see a close up photograph showing some of the detailing that went into producing this Saint Bernard statue, which was by Honore Jean Aristide Husson who was born in Paris in 1803 and entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts under David d'Angers to become a French sculptor, winning the Prix de Rome in 1830.

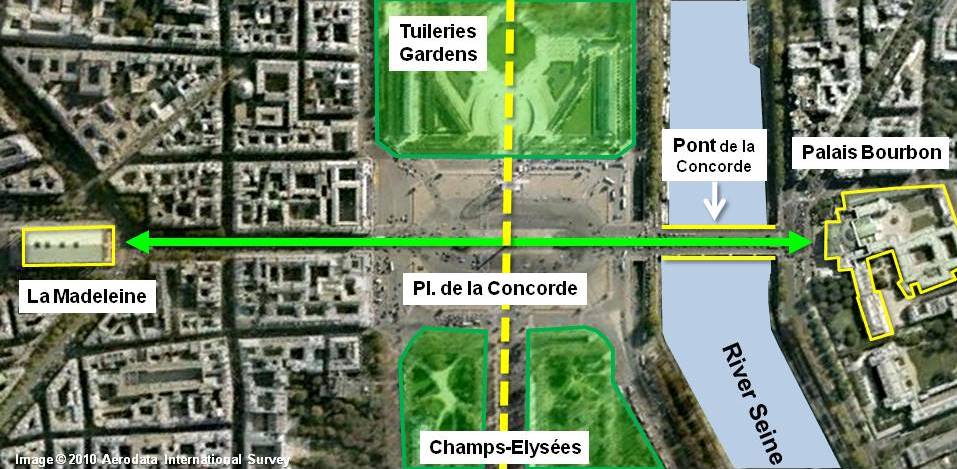

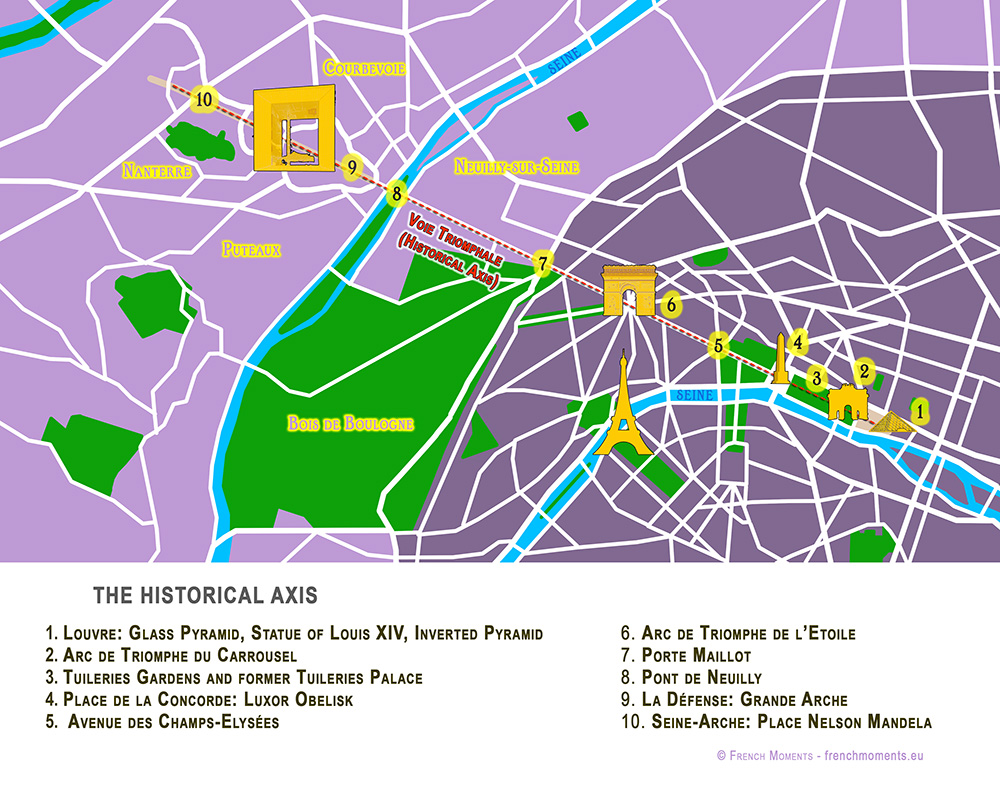

Honore Jean Aristide Husson, often just known as Honore Husson, received many different public commissions for statues, three of which are part of the series of famous men depicted on the facades of The Louvre, but he also worked on decorations for different tourist attractions like one of the fountains at the Place de la Concorde and several for different churches including the Eglise de la Madeleine.

Now Saint Bernard was born to a noble family and studied literature in order that he could study the bible, and becoming a monk, he is also known as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, due to the fact that he founded a monastery he named Claire Vallee, or Clairvaux, he was pronounced an Abbot by the bishop who was head of theology at the Notre Dame de Paris.

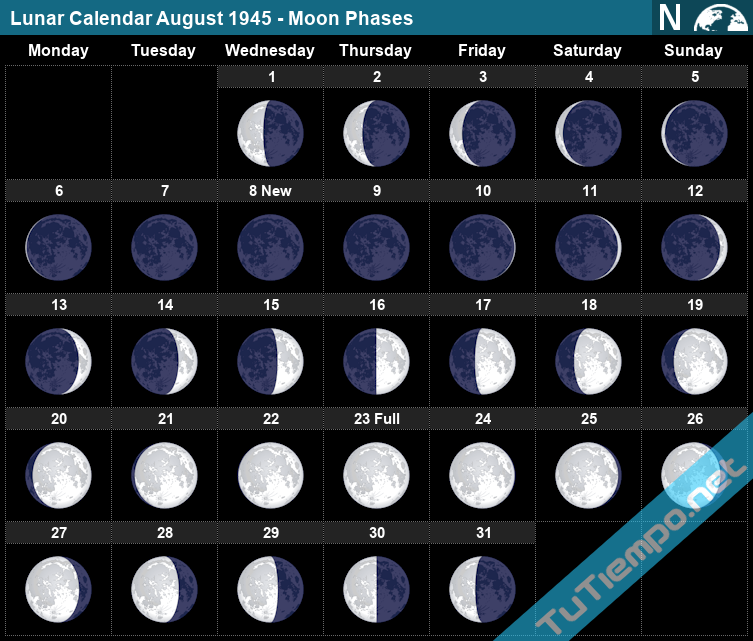

The theology and Mariology of Bernard have continued to be of major importance throughout the centuries and he was the first Cistercian monk to be placed on the Roman calendar of saints when canonized by Pope Alexander III on 18th January 1174, and 800 years after his death Saint Bernard was also given the title of Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius VIII, with his feast day being 20th August, the day Saint Bernard passed away in 1153.

So this image shows the location of the Saint Bernard statue within a niche on the eastern portico facade of the Eglise de la Madeleine, and this can be seen through the well recognisable Corinthian columns from the square named after this famous church, where even the funeral of Chopin took place.

https://www.eutouring.com/images_paris_statues_1029.html |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 16 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 17 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 18 de 30 de ce thème |

|

Secrets of the Knights Templar

They’re shrouded in mystery and conspiracy theories. A history scholar unpacks their real story.

Just mention the Knights Templar and the conspiracy theories start flying. But just who were the medieval Knights of the Temple? What was their job and what happened to them? Why do they still capture our imaginations? The Knights of the Temple—the Templars, for short—were established in the early 1100s under a Rule written by Bernard of Clairvaux,a famous Cistercian abbot. He modified existing Rules for religious monastic communities to fill the need for an armed order in light of the Crusades. This Rule and the Templars’ lifestyle became the model for about a dozen other religious military orders in the Middle Ages.

There are versions of these orders today, some of which can trace their lineage directly back to medieval ancestors. Others have chosen to emulate the original orders but adapt them to our times. These contemporary communities, now often composed of men and women, have turned to massive charitable and philanthropic projects and to protecting endangered Christians. One example of an adapted version of the medieval Templars is the Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem. Other modern expressions of medieval orders are the Knights of Columbus, the Knights and Dames of Malta (who trace their lineage back to the Hospitallers of St. John), and the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre.

Let’s take a look at the history behind the legend of these highly influential knights. It is a tale of medieval palace intrigue worthy of a Hollywood movie, which doesn’t have to make things up to be true.

Monk-Warriors

The story starts at the time of the Crusades. In 1095, Pope Urban II called for European Christian knights to stop fighting each other and to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. The pope’s speech sent thousands of knights, infantrymen, and a large supporting workforce streaming across Europe, resulting in the taking of Jerusalem in 1099. But these were not unified armies under a tight leadership team. Many knights behaved shamefully and certainly did not live up to the standards of chivalry and charity—even toward fellow Christians. Clearly there was a need for order, control, and standards.

The Templars had their origins at just this point in time. At first, there were about 10 French knights with their retinues escorting pilgrims from the Mediterranean coast to the holy city of Jerusalem and other sites in the area, such as Bethlehem, Bethany, Nazareth, and the Jordan River. The Muslims quickly regrouped, however, and began to take land back in this same period. Their victories led to the Second Crusade (1147‚ 1149), which was promoted by that same Bernard of Clairvaux.

By this time, it was clear that in order for the European Christians to maintain their hold on Jerusalem and keep the passages to Jerusalem safe, a more organized and permanent military presence needed to be set up. Most of the knights from the First Crusade simply left Jerusalem after taking the city in 1099. That group of French escorting knights, then, became the seed for the Templars.

In his Rule for the order, In Praise of the New Knighthood, written in 1128, Bernard of Clairvaux called these fighting men “knights of Christ.” He envisioned them as monk-warriors. The Templars and other orders at first saw their task as fighting to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land, even if that meant taking up arms while still holding to the three traditional monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Later, it meant protecting the faith from internal threats caused by heretics, once again by violence, if necessary.

Bernard captured the paradox when he said that the knights must be “gentler than lambs, yet fiercer than lions. I do not know if it would be more appropriate to refer to them as monks or as soldiers, unless perhaps it would be better to recognize them as being both.” He described the model Templar as “truly a fearless knight and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armor of faith just as his body is protected by armor of steel.”

Bernard also drew on the just-war tradition to say that, in certain circumstances, Templar violence was permitted and not sinful. “If he fights for a good reason, ” Bernard wrote, “the issue of his fight can never be evil.” Elsewhere in his Rule for the Templars, Bernard stated, “To inflict death or to die for Christ is no sin, but rather, an abundant claim to glory.” So for the Templars, fighting the infidel (literally, “the unfaithful ones”) meant the Muslims in the Holy Land.

The World of the Templars

The Templars took their name from their headquarters, situated on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This is where Solomon’s Temple had stood from about 970 BC until it was destroyed in 587 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar, who took the Israelites back to Babylon and left Jerusalem a backwater. Centuries later, about 20 BC, the client-king of the Romans, Herod, began to rebuild the Temple, which has come to be known as Herod’s Temple, Jesus’ Temple, or the Second Temple. It was barely completed before it was destroyed by Roman imperial forces in AD 70. Over a thousand years later, the elite knights envisioned by Bernard established their command center in what some still called Solomon’s Temple or Palace.

At its height during the crusading centuries, the Knights of the Temple included about 300 knights who had taken the three standard vows. Many of these vowed knights were in their 20s when they joined. They were supposed to be unmarried, free of debt, and of legitimate birth. They wore a distinctive tunic and wielded shields painted white with a prominent red cross.

The knights were joined by as many as 900 soldiers who were not noble and fought on foot—an infantry to complement the knights’ cavalry.

There would have been hundreds of others, which we would call support staff, employed by the order: blacksmiths, squires, women to cook and take care of clothing, and armorers. Some of the men among this support staff were like lay brothers in other religious orders, such as the Benedictines or Cistercians.

The Templars, like medieval monasteries and convents, were run very collaboratively. They held property and goods in common, making decisions about them and all other matters by vote. They were led by a grand master chosen by the vowed knights in an election.

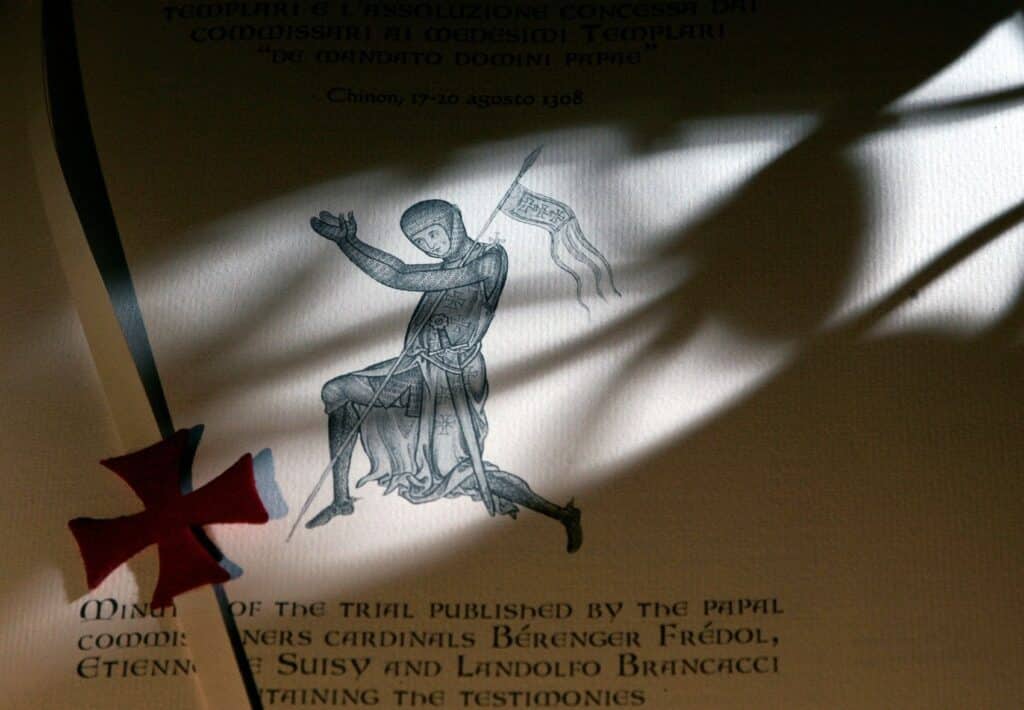

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

At the same time, however, elements of Templar life drew attention and led to rumors about them. They reported directly to the pope. They were also exempt from paying taxes, which increasingly became a big deal as they amassed huge areas of land. The Templars also attracted patrons quickly and in large numbers across western Europe.

They eventually enjoyed a network of nearly 2,000 castles, houses, and estates. (A modern-day analogy might be America’s super-wealthy robber baron families who built huge mansions they called cottages in the days before income tax.) We can see the mysteries that persist today started early.

Behind Closed Doors

Above all, the Templars held all of their deliberations and votes in secrecy. When they were fighting the infidel and protecting pilgrims, this was not an issue. But when the Crusades ran their course and Muslims systematically took back Holy Land territory and negotiated treaties for safe passage for Christian pilgrims, the Templars began to lose their reason for being there. When Muslims took Acre in 1291, Holy Land crusading effectively ended—leading to the next and final chapter for the Templars.

With no need to fight in the Holy Land, the Templars largely turned from military affairs to the worlds of finance, estate management, trade, banking, and overseeing investments along their network of tax-exemptproperties in Europe. They were likely the richest operation in the Middle Ages, essentially making them Europe’s ATM.

They were not without enemies, and their worst one was Philip IV, king of France. He is also known to history as Philip the Fair (le Bel), who reigned from 1285 to 1314. He had been trying to control the papacy and Church in France for some time by taxing the clergy without papal permission.

Effectively, he was trying to separate Catholic France from papal authority (later known as Gallicanism). Philiphad particularly tangled with a stubborn pope named Boniface VIII (1294‚ 1303). The king had even sent armed men to intimidate Boniface because the pope planned to excommunicate him. Boniface died shortly after this verbal assault and physical threat, perhaps as a result of the shock of the ugly episode.

Philip continued to pressure the papacy, this time in the person of the weak Pope Clement V (1305–1314), the first of the line of 14th-century popes who resided in Avignon and not Rome. This royalty-versus-papacy fightimp acted the Templars because Philip was in a towering pile of debt to the military order. Trying to get out of repaying, the French king accused the Templars of losing the Holy Land and not living up to their own high standards. Now he had the pope as a powerful tool to attack the Templars.

To take them down, Philip exploited the mystery behind the Templar practice of secrecy. He accused them of black magic, sodomy, and desecration of the cross and Eucharist. The French king engineered an overnight mass arrest of Templars in October 1307. Over the next four years, nearly all Templars were exonerated at trials held across Europe with the notable exception of France. There, after being tortured, some Templars confessed to doing things like spitting on the cross or denying Jesus during secret initiation rites. Many later took those confessions back, saying they had admitted such things only under pain and fear of death.

The End of an Era

The final act took place at the general Church council held at Vienne from 1311 to 1312. Philip was in charge and made sure only bishops supporting him and not Pope Clement were present, to the point of knocking the names of anti-royal bishops off the list of those invited. Even under pressure from the French king, the bishops still voted in a large majority against abolishing the Templars and said the charges against them were not proven.

Philip played his hand by threatening violence against a pope once again. He pressured Clement to condemn his papal predecessor Boniface as a heretic. What the French king really wanted was to get out of debt to the Templars and seize their assets. Pope Clement allowed the Templars to be railroaded by trading off that threat against Boniface, which would endanger his own position as a papal successor. Clement went against his bishops and suppressed the Knights of the Temple on his own papal authority. Quite simply, the pope had been bullied by the king and he gave in. Clement praised “our dear son in Christ, Philip, the illustrious king of France,” adding remarkably, “He was not moved by greed. He had no intention of claiming or appropriating for himself anything from the Templars’ property.”

But instead of handing their money and property over to Philip, as the king wanted, the pope showed some courage and assigned the Templar assets over to the Knights of the Hospital (the Hospitallers). Philip got his cut, of course, and was out of debt to an order that no longer existed, but he didn’t win entirely. Pope Clement never said whether or not the Templars were guilty of heresy or other crimes.

In fact, in 2001, Vatican researcher Barbara Frale discovered in the archives there a misfiled document that has come to be called the Chinon Parchment. This collection details trial and investigation records in Latin from 1307 to 1312. A measure of the continuing interest in the Templars may be found in the fact that a limited reproduction edition of the Chinon Parchment was produced in 2007. Titled Processus Contra Templarios (“Trial against the Templars”), each of the 799 copies cost over $8,000. The 800th copy was given for free to Pope Benedict XVI.

The Chinon Parchment proves that Pope Clement definitely believed in 1308 that the charge of heresy against the Templars was not true, although they were guilty of other, smaller crimes. But Clement just wasn’t strong enough to protect the Templars from annihilation. Finally, in 1314, the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay was burned at the stake as a lapsed heretic after he retracted his tortured confession and asserted his innocence. The history of the Templars had come to an end, but its reputation for secrecy and all of this palace intrigue seemed destined to make the myths about them continue to live on.

Sidebar: Conspiracies and the Templars

Because of their secrecy and power, the Templars have refused to die—in myth if not in fact. In part because people want to believe nearly anything about the Church (witness the legend of Pope Joan), the Templars are ripe for exploitation. Spend 10 minutes searching the Internet with the words Templars and conspiracy.

The Templars show up as mysterious and shadowy figures in Hollywood movies like The Da Vinci Code, where they are linked with the Priory of Sion as guardians of Jesus’ alleged descendants with Mary Magdalene. Take nearly any mysterious group or object and the Templars are linked by innuendo and rumor: the Temple Mount, the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Grail, the True Cross, the Shroud of Turin, and the Freemasons. One legend says they magically appeared to turn the tide of a battle in Scotland. Another claims they crossed the Atlantic Ocean before Columbus. Some of the wilder stories tie the Templars to President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and even Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation in 2013—and that’s before we get to the video games and The Templar Code for Dummies.

Perhaps all of this spookiness can be brought back to their end. It happened that the Templars were rounded up on Friday the 13th of October, 1307, which some people claim is the root of that feared calendar date. Moreover, as he went to his death at the stake, Grand Master Jacques de Molay supposedly issued a curse that he would meet PopeClement and King Philip with God within a year—and indeed both pope and king died shortly after.

https://www.franciscanmedia.org/st-anthony-messenger/secrets-of-the-knights-templar/ |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 19 de 30 de ce thème |

|

Bernard of Clairvaux

Above: Bernard of Clairvaux

by Alan Butler

Born Fontaine de Dijon France 1090

Died Clairvaux, near Troyes, Champagne France August 20th 1153

Bernard of Clairvaux may well represent the most important figure in Templarism. In our opinion past researchers have generally failed to credit St Bernard with the pivotal role he played in the planning, formation and promotion of the infant Templar Order. Whether an ‘intention’ to create an Order of the Templar sort existed prior to the life of St Bernard himself is a matter open to debate. (See ‘The Templar Continuum’ Butler and Dafoe, Templar Books 2,000).

The son of Tocellyn de Sorrell, Bernard was born into a middle-ranking aristocratic family, which held sway over an important region of Burgundy, though with close contacts to the region of Champagne. There is some dispute as to whether Bernard’s father had fought in the storming of Jerusalem in 1099, and indeed whether he died in the Levant. The question appears to be easily answered for in the small Templar type Church in St Bernard’s birthplace there is a marble plaque that states the Church was built by St Bernard’s mother in thanks for the safe return of her husband from the Crusade.

St Bernard was a younger member of an extremely large family. He appears to have received a good, standard education, at Chatillon-sur-Seine, which fitted him, most probably, for a life in the Church, which, of course, is exactly the direction he eventually took. Many stories exist regarding Bernard’s early years – his visions, torments and realisations. All of these were attributed to Bernard after his canonisation and therefore must surely be taken with a pinch of salt. What does seem evident is that Bernard was bright, inquisitive and probably tinged with a sort of genius. Certainly he was a fantastic organiser and possessed a charisma that few could deny.

St Bernard enters history in an indisputable sense at the age of 23 years, when together with a very large group of his brothers, cousins and maybe other kin, (probably between 25 and 30) he rode into the abbey of Citeaux, Dijon. This abbey was the first Cistercian monastery and had been set up somewhat earlier by a small band of dissident monks from Molesmes. Much can be found elsewhere in these pages relating specifically to the Cistercians. At the time of St Bernard’s arrival the abbey was under the guiding hand of Stephen, later St Stephen Harding, an Englishman.

Bernard announced his determination to follow the Cistercian way of life and together with his entourage he swamped the small abbey, swelling the number of brothers there to such an extent that it was inevitable that more abbeys would have to be formed.

Only three years later St Bernard, still an extremely young man, (25 years) was dispatched, together with a small band of monks, to a site at Clairvaux, near Troyes, in Champagne, there to become Abbott of his own establishment. It is known that the land upon which Clairvaux was built was donated by the Count of Champagne, based at the nearby city of Troyes.

St Bernard was a visionary, a man of apparently tremendous religious conviction. He could be irascible and domineering at times, but seems to have been generally venerated and well liked by those around him. Bernard suffered frequent bouts of ill health, almost from the moment he joined the Cistercians. This continued for the remainder of his life and may have demonstrated an inability on the part of his digestive system to cope with the severe diet enjoyed or rather endured by the Cistercians at the time.

Bernard’s influence grew within the established Church of his day. With a mixture of simple, religious zeal and some extremely important family connections, this little man involved himself in the general running, not only of the Cistercian Order, but the Roman Church of his day. Bernard was instrumental in the appointment of GREGORIO PAPARESCHI, Pope Innocent II in the year 1130, despite the fact that not all agencies supported the man for the Papal throne. Bernard walked hundreds of miles and talked to a great number of influential people in order to ensure Innocent’s ultimate acceptance. His success in this endeavour marked St Bernard as probably the most powerful man in Christendom, for as ‘Pope Maker’ he probably had more influence than the Pontiff himself.

This appointment should not be underestimated, for it was Pope Innocent II who formally accepted ‘The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon’ (The Knights Templar) into the Catholic fold. This he did, almost certainly, at the behest of Bernard and possibly as a result of promises he had made to this end at the time Bernard showed him the support which led to the Vatican.

To understand St Bernard’s importance to Cistercianism it is first necessary to study the Order in detail. In brief however it would be fair to suggest that Bernard’s own personality, drive and influence saw the Cistercians growing from a slightly quirky fringe monastic institution to being arguably the most significant component of Christian monasticism that the Middle Ages ever knew.

In addition to this St Bernard consorted with Princes, Kings and Pontiffs, even directly ‘creating’ his own Pope, BERNARDO PAGANELLI DI MONTEMAGNO (Eugnius III) who became Pontiff in 1145. This man had been a noviciate of St Bernard at Clairvaux and was, in all respects, St Bernard’s own man. From this point barely a decision was made in Rome that was not influenced in some way by St Bernard himself.

Much could be written about the ‘nature’ of St Bernard. He was a staunch supporter of the Virgin Mary, a visionary and a man who had a profound belief in an early and very ‘Culdean’ form of Christianity. This is exemplified by the short verse he once wrote.

‘Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.’

St Bernard staunchly supported what amounted to an utter veneration of the Virgin Mary for the whole of his life and was also an enthusiastic supporter of a rather strange little extract from the Old Testament, entitled ‘Solomon’s Song of Songs’.

How and why St Bernard became involved in the formation of the Knights Templar may never be fully understood. There is no doubt that he was blood-tied to some of the first Templar Knights, in particular Andre de Montbard, who was his maternal uncle. He may also have been related to the Counts of Champagne, who themselves appear to have been pivotal in the formation of the Templar Order.

For whatever reason St Bernard wrote the first ‘rules’ of the Templar Order. He may have undertaken this task personally and they were based, almost entirely, on the Order adopted by the Cistercians themselves. The Templars were officially declared to be a monastic order under the protection of Church in Troyes in 1139. Bernard went further and insisted that Pope Innocent II recognised this infant order as being solely under the authority of the Pope and no other temporal or ecclesiastical authority. It is a fact that the Templars venerated St Bernard from that moment on, until their own demise in 1307. St Bernard’s influence on the Templars is therefore pivotal to the whole of the movement’s aims and objectives and in our opinion no researcher should ever underestimate Bernard’s importance with this regard.

St Bernard travelled extensively, negotiated in civil disturbances and, surprisingly for the period, was instrumental in preventing a number of pogroms taking place against Jews in various locations within what is present day France. A staunch supporter of an Augustinian view of the mystery of the Christian faith, St Bernard was fiercely opposed to ‘rationalistic’ views of Christianity. In particular he was a staunch opponent of the dialectician ‘Peter Abelard’, a man whom St Bernard virtually destroyed when Abelard refused to accept Bernard’s own criticism of his radical ideas.

Although travelling extensively on many and varied errands during his life, St Bernard always returned to his own abbey of Clairvaux, which it seems (to us at least) had been deliberately built in a location that allowed free travel in all directions. It is suggested that Clairvaux was peopled with all manner of scholars, some of whom may well have been Jewish scribes. It is also true to say that if Citeaux remained the ‘head’ of the Cistercian movement during the life of St Bernard, Clairvaux lay at its heart. Clairvaux became the Mother House of many new Cistercian monasteries, not least of all Fountaines Abbey in Yorkshire, England, which itself was to rise to the rank of most prosperous abbey on English soil.

St Bernard died in Clairvaux on August 20th 1153, a date that would soon become his feast day, for St Bernard was canonised within a few short years of his death. Space here does not permit a full handling of this extraordinary man’s life or his interest in so many subjects, including architecture, music and (probably) ancient manuscripts. After his death a cult of St Bernard rapidly developed. At the time of the French Revolution St Bernard’s skull was taken for safekeeping to Switzerland, eventually finding its way back to Troyes. It is now housed in the Treasury of Troyes Cathedral and can be seen there, together with the skull and thighbone of St Malachy, a friend and contemporary of St Bernard.

A much fuller and more comprehensive detailed biography of St Bernard’s life can be found in ‘The Knights Templar Revealed’ Butler and Dafoe, Constable and Robinson – 2006.

About Us

TemplarHistory.com was started in the fall of 1997 by Stephen Dafoe, a Canadian author who has written several books on the Templars and related subjects.

Read more from our Templar History Archives – Templar History

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 20 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 21 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 22 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 23 de 30 de ce thème |

|

| Enviado: 21/10/2024 10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 24 de 30 de ce thème |

|

Hugo de Payns o Payens (castillo de Payns, cerca de Troyes, Francia 9 de febrero de 1070-Reino de Jerusalén, 24 de mayo de 1136) fue el fundador y primer maestro de los Caballeros templarios y uno de los primeros nueve caballeros. En asociación con Bernardo de Claraval, creó la Regla latina, el código de conducta de la Orden.

Hijo de Gautier de Montigny y nieto de Hugo I, Señor de Payns, su infancia y su juventud se ven influidas por el ambiente de reforma religiosa que se desarrolla en la Champaña y que dará figuras de la talla de san Roberto de Molesmes, fundador de las abadías de Molesmes y Cîteaux, o la de san Bernardo de Claraval, impulsor de la reforma del cister y mentor eclesiástico de la misma Orden del Temple.

De la ferviente pasión religiosa de Hugo II de Payns es muestra su breve paso como monje por la abadía de Molesmes, tras la muerte de su primera esposa Emelina de Touillon, con la que se había desposado hacia el 1090. Fruto de este matrimonio nació su hija Odelina, futura señora de Ervy.

Vasallo fiel del conde Hugo I de Champaña,1 Hugo II de Payns abandona los hábitos y a partir del año 1100 se integra plenamente como uno de los principales miembros de la Corte champañesa, uniendo en su persona el señorío de Montigny y el de Payns.

Es muy probable que Hugo II de Payns realizara su primer viaje a Tierra Santa junto al conde de Champaña en 1104-1107. Tras regresar de este, y para ayudar a consolidar las pretensiones políticas de su señor, casó en segundas nupcias con Isabel de Chappes (entre 1107 y 1111), perteneciente a una de las familias más importantes del sur de la Champaña. Del matrimonio nacieron cuatro hijos: Teobaldo, futuro Abad de Santa Colombe de Sens; Guido Bordel de Payns, heredero del señorío; Guibuin, vizconde de Payns, y Herberto, llamado el ermitaño. Sin embargo, la pasión religiosa que sentía le llevó a tomar votos de castidad en 1119 y a partir nuevamente a Tierra Santa, donde creó, un año más tarde, la que llegaría a ser la Orden Militar más importante de la Cristiandad: La Orden del Temple.

Se afirma[cita requerida] que los otros caballeros eran Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, Archambaudo de Saint Agnan, Andrés de Montbard (tío materno de San Bernardo de Claraval), Godofredo Bison, y otros dos de los que solo se conoce su nombre, Rolando y Gondamero. Se desconoce el nombre del noveno caballero, aunque hay quien piensa que pudo ser Hugo, conde de Champaña.

En 1127 Hugo II de Payns regresa a Europa acompañado por Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, y dos hermanos más, de nombre Raúl y Juan, con el fin de reclutar nuevos miembros para la Orden, tomar posesión de las numerosas donaciones que habían sido otorgadas a esta y para organizar las primeras encomiendas de la Orden en Occidente (casi todas ellas en la región de la Champaña). Así pues, Hugo inicia un periplo que le lleva por Roma - a fin de solicitar del papa Honorio II un reconocimiento oficial de la Orden y la convocatoria de un concilio que debatiera el asunto - la Champaña (otoño de 1127); Anjou y Poitou (abril y mayo de 1128), Normandia, Inglaterra y Escocia (verano de 1128) y Flandes (otoño de 1128).

Hugo y sus compañeros regresan en enero de 1129 a la Champaña para tomar parte en el Concilio de Troyes, un concilio de la Iglesia católica, que se convocó en la ciudad francesa el 13 de enero de 1129, con el principal objeto de reconocer oficialmente a la Orden del Temple. En dicho concilio estuvieron presentes: el cardenal Mateo de Albano (representante del Papa); el arzobispo de Reims y el de Sens; diez obispos; ocho abades cistercienses de las abadías de Vézelay, Cîteaux, Clairvaux (que en este caso no era otro sino San Bernardo), Pontigny, Troisfontaines y Molesmes; y algunos laicos entre los que destacan Teobaldo II de Champaña, el conde de Campaña, André de Baudemont, el senescal de Champaña, el conde de Nevers y un cruzado de la campaña de 1095.

Hugo de Payns relató en este concilio los humildes comienzos de su obra, que en ese momento solo contaba con nueve caballeros, y puso de manifiesto la urgente necesidad de crear una milicia capaz de proteger a los cruzados y, sobre todo, a los peregrinos a Tierra Santa, y solicitó que el concilio deliberara sobre la constitución que habría que dar a dicha Orden.

Se encargó a San Bernardo, abad de Claraval, y a un clérigo llamado Jean Michel la redacción de una regla durante la sesión, que fue leída y aprobada por los miembros del concilio.

Tras el concilio de Troyes, Hugo II de Payns nombró a Payen de Montdidier Maestre Provincial de las encomiendas sitas en territorio francés y en flandes, y a Hugo de Rigaud Maestre Provincial para los territorios del Languedoc, la Provenza y los reinos cristianos hispánicos y tras ello, regresó a Jerusalén dirigiendo la Orden que el mismo había creado durante casi veinte años hasta su muerte en el año 1136 (el 24 de mayo según el obituario del templo de Reims), haciendo de ella una influyente institución militar y financiera internacional.

Un cronista del siglo XVI escribió que fue enterrado en la Iglesia de San Jaime de Ferrara.2

No hay un retrato contemporáneo de él.

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 25 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 26 de 30 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 27 de 30 de ce thème |

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 28 de 30 de ce thème |

|

https://knightstemplarorder.org/templar-order/survival-lineage/ |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 29 de 30 de ce thème |

|

Templar Nation

Popular name: Templar Nation

Continent: Europe

Capital: N/A

Language: Italian

Other languages: English, French

Area: N/A

Population: 30 000

Currency: Euro

Religion: Christian-yeoshuite

Representative (movement that represents): N/A

Contact person: N/A

Website: View Website

Email: info@gov-nt.com

In 1118, at the behest of the Cistercian Abbot of Clairvaux, Bernard of Fontaine-lès-Dijon, the Templar people was formed in the form of a lay-monastic Order and was called Pauperes Commilitones Christi Templique Salomonis.

The Templar people were born from this constitution.

The Pope's appeal during this early part of the Middle Ages was so resounding that the constitution of the Templar people was immediate.

The historically best known members of the Templar People were the famous Templar Knights, but there were numerous who served the Order.

In fact, in addition to the members of the Order, the Templar people were also composed of all the people who revolved around the Order:

squires, waiters, cooks, teachers, farriers, artisans, etc.

Moreover, all the family members of the persons indicated above also contributed to the Templars' people.

As an indication, the Templar people around 1200 had about 22,000 Knights of Arms in Europe (historical data preserved in the National Library of France in Paris).

At the time it was normal that there were thirty people following a knight in arms, so we can estimate the Templar Nation composed of about 150,000 people.

For comparison, during the same period the city of Nice, in France, had about 3,000 inhabitants.

The Templar people (knights in arms, family, servants), continued their existence until the early 1300s, to be precise until 1307, the year in which began a real attempt to exterminate by the Kingdom of France (King Philip IV) and the State of the Catholic Church (Pope Clement V).

Despite the perpetrated genocide (over 100,000 people were killed, with a population that at that time had 170,000 people), the Templar people continued its existence.

Initially, the Templars followed the Order in its movements, but over the centuries, permanent places of residence were created in the various cities called Priories, Granges, Commanderies.

Despite the various historical vicissitudes, the Templars have arrived until today, reunited in a nation, despite being dispersed in different states and with different citizenships.

In 2015 the members of the Templar Order (about 1500 people), members of other organizations that gathered a part of the Templar people and other members of the unorganized Templar people, asked the Grand Prior of V.E.O.S.P.S.S. - Pauperes Commilitones Christi Templique Salomonis to bring together the Templar people in a real nation and appointed a Council of Regency to organize the nation.

After three years of studies, evaluations and consultations (many international law experts were consulted), in 2018 the Regency Council elected a President and issued a Constitutional Charter creating, through the principle of self-determination of the peoples, the Templar Nation.

The Regency Council has also written a Constitutional Charter, which represents the constitutional basis of the Templar Nation.

The Templar Nation today is formed by the Templar people, that is, by those people who are linked by ideological principles and a common culture, by a centuries-old ancestry and, not least, by a common religiosity (the Templars are defined as Christian-yeoshuites, because faithful to the word of Jesus Christ).

From a legal point of view, under international law, the subject holder of the right to self-determination is the people as a subject distinct from the state.

The principle of self-determination of a people constitutes a norm of general international law, that is a norm that produces legal effects (rights and obligations) for the whole Community of States.

Moreover, this principle also represents a norm of “ius cogens”, that is, an imperative right: it means that it is a supreme and inalienable principle of international law, for which it cannot be derogated by an international convention.

Therefore, a people has the right to self-determination and to choose their own political regime, regardless of whether he have been subject to foreign domination.

A community of individuals (a people) who share some common characteristics such as language, history, traditions, culture, ethnicity and eventually a government, constitutes a nation, from the Latin “natio”, in english "birth", (Federico Chabod, The idea of a nation, Laterza, Bari 1961).

According to Johann Gottfried Herder in the life of a nation, the unity of culture and language comes first of political unity, of the State and of the constitution (Kulturnation).

The nation thus bases its cohesion on language, culture and tradition, not on the abstract rigidity of a political obligation.

Ernest Renan defines the nation as the soul and spiritual principle of a people, which enjoys a rich legacy of memories and current consensus.

Some authors, such as Jürgen Habermas, consider the concept of nation as a free social contract between peoples or between persons constituting a people, who recognize themselves in a common Constitution, thanks to the concept of "group of belonging".

It follows that the nation exists as long as it finds its place in the minds and hearts of its constituents.

Therefore, a nation is a community of individuals (a people), conscious of being bound by a common historical, linguistic, cultural and religious tradition.

In the case of the Templar people, this is specifically about a "nation without a state", because the people belong to different States.

The Templar Nation adheres to the "International Convention on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights" of 1966 (entered into force in 1976), to the "Universal Declaration of the Rights of Peoples", also called "Algiers Charter", dated 1976, and the "United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights" (UN) of 10 December 1948.

Given that the current Templar population is quite small and that over the centuries has been the object of real attempts to exterminate by several States, as well as “damnatio memoriae”, it is right to define the Templar people as a "supranational minority" to be protected.

All those who, for historical, cultural or ideological reasons, recognize themselves in the ideals of the Templars, can join the Templar Nation and obtain the Nationality.

https://www.unrepresentedunitednations.org/en/unrepresented-united-nations-directory/templar-nation |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 30 de 30 de ce thème |

|

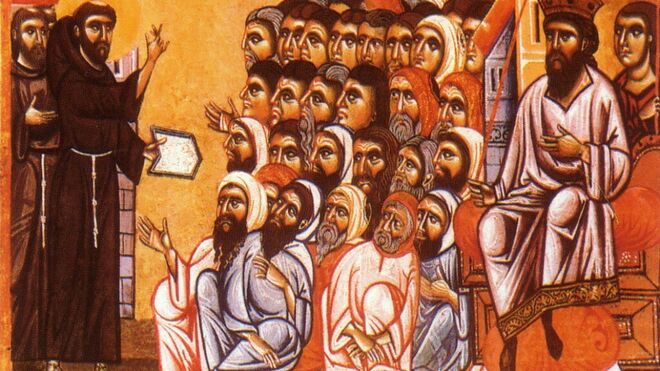

"Quiso desactivar las guerras de religiones respetando la convivencia cívica"J. J. Tamayo: "El Encuentro de Francisco de Asís con el sultán Al Kamil inauguró la cultura del diálogo"

Encuentro de Francisco de Asís y el Sultán, modelo del diálogo interreligioso

https://www.religiondigital.org/vida-religiosa/Tamayo-Encuentro-Francisco-Asis-Kamil-islam-sultan_0_2163383655.html |

|

|

Premier Premier

Précédent

16 a 30 de 30

Suivant Précédent

16 a 30 de 30

Suivant

Dernier

Dernier

|

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

![Regreso Al Fururo III (Back To The Future III) [1990] –, 40% OFF](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BYzgzMDc2YjQtOWM1OS00ZjhhLWJiNjQtMzE3ZTY4MTZiY2ViXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNDQ0MTYzMDA@._V1_.jpg)