|

|

Posted on Apr 28, 2019

On March 19, 2109 The Galaxy reported that China was close to launching its “artificial sun” promising a future of ‘limitless clean energy –a Chinese “Green New Deal”. Unlike nuclear fission, fusion emits no greenhouse gases and carries less risk of accidents or the theft of atomic material.

Sometimes called an “artificial sun” for the sheer heat and power it produces, China’s doughnut-shaped Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) that juts out on a spit of land into a lake in eastern Anhui province, has notched up a succession of firsts, reports AFP. Officials announced that the machine which will hold the ‘artificial sun’, called the HL-2M Tokamak, could be built this year using nuclear fusion in which hydrogen from sea water and readily available lithium is heated to more than 150 million°C.

The current Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) reactor in Hefei has created temperatures as hot as the interior of the sun. In November, it became the first facility in the world to generate 100 million degrees Celsius (212 million Fahrenheit)—six times as hot as the sun’s core. These mind-boggling temperatures are crucial to achieving sustainable nuclear fusion reactions, which promise an inexhaustible energy source.

“Stupendous” –China’s Leap to Space-Based Solar Power: ‘Will Beam Sun’s Energy Back to Earth’

“The artificial sun’s plasma is mainly composed of electrons and ions and the country’s existing Tokamak devices have achieved an electron temperature of over 100 million degrees C in its core plasma, and an ion temperature of 50 million C, and it is the ion that generates energy in the device,” said Dr Duan Xuru, an official at the China National Nuclear Corporation, according to China’s Global Times.

HL-2M Tokamak is expected to increase the electricity intensity from one mega amperes to three mega amperes, an important step to achieve nuclear fusion, a spokesperson surnamed Liu with the press office of the Southwestern Institute of Physics (SWIP), affiliated with China National Nuclear Corporation, told the Global Times.

“The Milky Way Base” –China Names First Human-Technology Landing Site on Moon’s Far Side

For instance, the deuterium (also known as heavy hydrogen) extracted from one liter of seawater releases the energy equivalent of burning 300 liters of gasoline in a complete fusion reaction, Liu said.

The “artificial sun” aims to release nuclear fusion in the same way as the sun by using deuterium and tritium (radioactive hydrogen-3), and finally generate electricity. It is clean energy that will not generate waste, which makes it ideal for people to use in the future, Liu said.

https://dailygalaxy.com/2019/04/earths-second-sun-chinas-fusion-future-the-holy-grail-of-unlimited-energy-weekend-feature/

|

|

|

|

|

En la fusión por confinamiento magnético, el combustible se comprime mediante campos magnéticos mientras se calienta. Foto: EUROfusion Dennis Youchison, del Laboratorio Nacional de Oak Ridge, es el director del programa Red de Innovación para Energía de Fusión Nuclear (INFUSE), del Departamento de Energía (DOE) de Estados Unidos.

Es un ingeniero con amplia experiencia en componentes de plasma. Como director adjunto ha sido designado Ahmed Diallo, un acreditado investigador que trabaja en el Laboratorio de Física del Plasma de la Universidad de Princeton.

El Departamento de Energía ha creado el programa INFUSE con el fin de alentar a las asociaciones de investigación público-privadas para superar los desafíos planteados para en desarrollo de la energía de fusión.

Sinergias público-privado para lograr la fusión nuclear

El programa, patrocinado por la Oficina de Ciencias de la Energía de Fusión (FES) dentro de la Oficina de Ciencia del DOE, se enfoca en acelerar el desarrollo de la energía de fusión a través de colaboraciones de investigación entre la industria y el complejo de laboratorios nacionales del DOE con su experiencia e instalaciones científicas.

«Creemos que existe un potencial real para la sinergia entre la industria y los esfuerzos de investigación patrocinados por el Gobierno en la fusión nuclear», según James Van Dam, del Fusion Energy Sciences.

La energía de fusión es inagotable, limpia y barata. Se basa en la fusión de núcleos ligeros como el hidrógeno, deuterio y tritio. Imagen: brgfx / Freepik «Estoy entusiasmado con el potencial de INFUSE y creo que este paso inculcará una nueva vitalidad a toda la comunidad de la fusión», opina Youchison. «Múltiples compañías privadas en los Estados Unidos -explica- están buscando sistemas de energía de fusión, y queremos contribuir con soluciones científicas que ayuden a hacer de la fusión una realidad».

A través de INFUSE, las empresas pueden obtener acceso a las instalaciones y los trabajos de investigadores del DOE, expertos en el desarrollo de sistemas de energía de fusión.

Propuestas de proyectos de investigación

La gestión del programa de ORNL, situado en el Laboratorio Nacional de Oak Ridge, emplea a científicos e ingenieros con experiencia en plasma, ciclos de combustible, desarrollo de materiales y plataformas informáticas de sistemas de fusión, entre otras.

Así, Youchison recuerda que “ORNL ha sido líder mundial durante más de 75 años. Hoy tenemos un lugar que permite experimentos de fusión nuclear nuevos e innovadores, así como recursos que no existen en ningún otro lugar del mundo”.

ORNL y PPPL se unen a los laboratorios nacionales Pacific Northwest, Idaho, Brookhaven, Lawrence Berkeley, Los Alamos y Lawrence Livermore como participantes en el programa INFUSE. La presentación de propuestas de proyectos de investigación finalizan el 30 de junio y las notificaciones de adjudicación se esperan para el 10 de agosto.

Fusión nuclear: la energía del sol

La energía de fusión es la que se produce en el interior del Sol y las estrellas. Es inagotable, limpia y barata. No tiene nada que ver con la energía de fisión, ya que en lugar de romper núcleos pesados como el uranio, se basa en la fusión de núcleos ligeros como el hidrógeno, deuterio y tritio.

Los analistas subrayan que la demanda de energía lleva décadas aumentando y que fuentes actuales de energía fósiles como el carbón, petróleo y gas son limitadas, además de contribuir notablemente al aumento de la contaminación. Asimismo, son muchas las personas que consideran peligrosa a la fisión nuclear, mientras que las energías alternativas (eólica, solar, mareomotriz, entre otras) todavía no cubren las necesidades más elementales por si mismas.

La energía de fusión es la que se produce en el interior del Sol y las estrellas. El combustible para la fusión es abundante y puede proporcionar la humanidad con energía durante millones de años. Así, el Deuterio se puede obtener a partir del agua, mientras que el Tritio se puede obtener del Litio, que puede extraerse de las minas. Además, esta fuente de energía no produciría emisiones de carbono y sería capaz de proporcionar energía según las necesidades.

Llegados a este punto, recordar que, en laboratorio, los científicos pueden obtener la reacción de fusión de varias maneras. Son dos las principales rutas hacia un reactor de fusión que se están explorando actualmente. Por un lado, la fusión inercial, en la que se calienta y comprime una pastilla de combustible mediante láseres. La otra forma es la fusión por confinamiento magnético, en la que el combustible se comprime mediante campos magnéticos mientras se calienta.

https://biotechmagazineandnews.com/ee-uu-apuesta-por-de-fusion-nuclear/ |

|

|

|

|

La carrera por la fusión nuclear acelera e Italia y el MIT dispondrán de la primera planta en 2025

Roma exhibe en la mayor feria tecnológica europea un simulador de una jaula magnética para mostrar su confianza en el próximo desarrollo de una fuente de energía inagotable, verde y segura

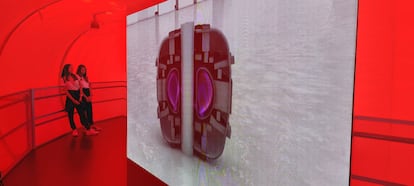

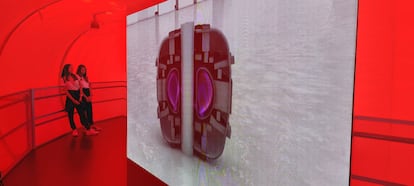

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/7EIGHO6T3FDAZKFGWDYTSIUAAI.JPG) Visitantes de la Maker Faire de Roma esperan el pasado viernes para acceder al simulador de una jaula magnética de un reactor de fusión nuclear. DAVLAO

El mundo acelera en la búsqueda de una fuente de energía inagotable, verde y segura en la fusión nuclear. Mientras el Reino Unido dibuja un plan para disponer del primer prototipo de reactor en 2032 y el ITER (el consorcio de tres continentes que construye el mayor complejo en Francia) lucha por mantener los plazos dentro de esta década, el grupo energético italiano Eni, en colaboración con el Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), asegura que “dispondrá de una primera planta en Estados Unidos en 2025″, según ha confirmado Mónica Spada, jefa de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica de la compañía italiana, durante la Maker Faire (Feria de Creadores), clausurada el domingo en Roma. La crisis energética global ha convertido el maratón científico que busca reproducir el poder del Sol en una carrera de velocidad.

La fusión nuclear es la puerta a una esperanza mundial que Spada resume recordando al fundador de Eni, Enrico Mattei: “Llevar la energía a todos, de forma sostenible y que sea un bien común”. Para este logro se intenta reproducir un fenómeno solar mediante la unión de dos núcleos de átomos ligeros para formar otro núcleo liberando energía. En estos momentos se utilizan deuterio y tritio, isótopos del hidrógeno. Ambos generan una nueva partícula que libera 17.6 mega-electrón voltios [MeV], lo que significa que una cantidad de 2,5 gramos de ambos genera una energía similar a la de un campo de fútbol lleno de carbón en combustión. Su potencial frente a cualquier combustible fósil es 10⁷ superior.

MÁS INFORMACIÓN

Los principales problemas son las altas presiones y temperaturas del plasma de fusión (el combustible de un reactor), que pueden ser superiores a las del Sol: 200 millones de grados en el centro. Las investigaciones actuales intentan confinar este plasma en jaulas magnéticas para mantenerlo levitando en el vacío dentro del reactor con el fin de minimizar los efectos del contacto con las paredes y evitar las fluctuaciones.

Para Spada, la tecnología necesaria ya está madura y prevé contar con la primera planta en tres años en Estados Unidos, donde Eni forma parte de Commonwealth Fusion Systems, una corporación surgida del MIT en 2018: “Empezamos a trabajar en este proyecto porque fuimos los primeros en entender que hay un enorme potencial. Estamos trabajando para hacerlo realidad lo antes posible. La primera planta Sparc estará en 2025 y, aunque no estará conectada a la red en esa fecha, será el primer prototipo”. Sparc es un dispositivo compacto de fusión neta, con un tamaño medio, pero con un campo magnético muy poderoso. La previsión para contar con un sistema completo que distribuya energía se sitúa en 2028.

Para esto es necesario superar otro reto, una vez conseguido el confinamiento: que la energía generada sea superior a la empleada para conseguir la fusión. El equipo de Joint European Torus (JET), liderado por el Reino Unido, ha conseguido a principios de año un récord: 59 megajulios durante cinco segundos, el equivalente a la energía necesaria para hervir el agua de 60 teteras. Aunque no parece mucho, el récord duplica al conseguido hace 25 años, avala el diseño de los actuales reactores y muestra el camino para conseguir que sean eficientes.

La confianza de Eni en la fusión nuclear le ha llevado a levantar el mayor pabellón individual en la Maker Faire de Roma, la mayor exhibición tecnológica europea, organizada por la Cámara de Comercio de la capital italiana, con financiación de la UE, entre otras instituciones, y a la que ha sido invitado EL PAÍS. La instalación, creada por los arquitectos Carlo Ratti e Italo Rota (autores del pabellón de su país en la Expo de Dubai de 2020), simula un viaje por el interior de una jaula magnética. “Los visitantes pueden sentirse como las partículas de la fusión”, resume Ratti.

Dos visitantes de la Maker Faire de Roma, en el interior del simulador de una jaula magnética.

“Es como un teaser [una pequeña muestra] a escala donde el público puede entrar y comprender el proceso. Lo importante es asegurar que el visitante se involucre con lo real, que pueda entender cómo podemos mejorar gracias a la ciencia. Queríamos contar la historia, pero también asegurarnos de que el espectador pueda verla, adentrarse en ella.”, explica el arquitecto.

El otro desafío ha sido elaborar un mensaje para una audiencia heterogénea que va desde los estudiantes de secundaria y bachillerato hasta los expertos y empresarios que tienen en Roma el punto de encuentro con la tecnología del futuro. “Teníamos que alcanzar un término medio de lo comprensible, pero sin que fuera simplista”, añade Ratti.

También está convencido del futuro de la fusión nuclear, para la que hay cientos de compañías y científicos trabajando en todos los ámbitos, desde la física a la ingeniería, pasando por los expertos en materiales. Como ellos, advierte de que la solución nuclear no será única. “No va a haber una sola fuente de energía. Habrá una mezcla, imprescindible para descarbonizar el planeta. La nuclear va a ser una más”, comenta.

Su visión de un futuro cada vez más inmediato es que estas instalaciones diversas y acordes con el potencial de cada zona “se van a insertar de una manera cotidiana en las ciudades, en el paisaje urbano”. Y no solo en las grandes capitales, porque Ratti cree que “ni Europa ni Estados Unidos necesitan desarrollar grandes urbes porque la población en estas empieza a decrecer”. “Estamos implicados en nuevos proyectos relacionados con agricultura urbana. Hacerlo todo más sostenible es el corazón de lo que la arquitectura tiene que hacer hoy”, concluye.

Italo Rota añade que la base de este nuevo futuro, “donde la tecnología es tan importante”, es la participación. Ha sido uno de los elementos clave para el diseño del simulador de reactor de fusión nuclear: “Que la gente entienda todo el proceso, no solo la carga de un coche eléctrico, por ejemplo, sino dónde se produce, cómo se distribuye y cómo se consume”.

Rota defiende un cambio de mentalidad individual para favorecer las transformaciones colectivas y la combinación de lo tecnológico con lo natural. “Muchos elementos de la vida están en la tecnología y esta es parte de la vida. Tienen que haber muchas soluciones para las ciudades, para el cuerpo de la población, y hay que encontrar el equilibrio”

https://elpais.com/tecnologia/2022-10-10/la-carrera-por-la-fusion-nuclear-acelera-e-italia-y-el-mit-dispondran-de-la-primera-planta-en-2025.html |

|

|

|

|

Paris Climate Talks: Nuclear Fusion Is The 'Holy Grail' Of Clean Energy Technology

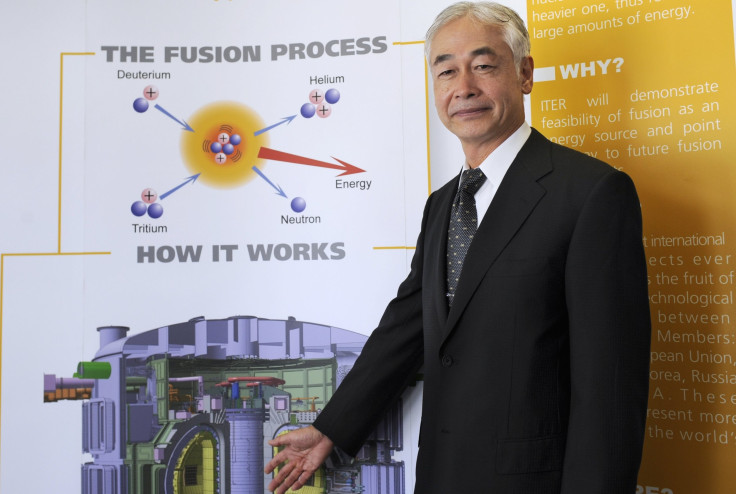

Osamu Motojima, the general director of the nuclear fusion project ITER from July 2010 to March 2015, poses with a poster about the project in Cadarache, France, July 28, 2010. ANNE-CHRISTINE POUJOULAT/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

ICONS BY DANIL POLSHIN AND CHRIS TUCKER FROM THE NOUN PROJECT

On a sprawling campus in southern France, a revolutionary kind of power plant is steadily rising from the ground. Scientists and engineers from dozens of countries are building a facility that will eliminate all the negatives of today’s power supplies -- greenhouse gas emissions, toxic air pollution, radioactive meltdowns -- while still providing massive amounts of electricity around the clock. At least, that’s the goal.

The International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER) project will use nuclear fusion, a technology that energy experts call the “holy grail” of modern electricity. If successful, fusion reactors could replace most of the world’s coal, oil and natural gas-fired power plants. They would fill in the gaps created by wind and solar energy, which are not available around the clock, without costly battery systems.

“If we can break through in this area, then we will truly change the energy industry,” said Wal van Lierop, president and CEO of Chrysalix Energy, an investor in the Canadian nuclear fusion startup General Fusion. “These are unicorns in the making.”

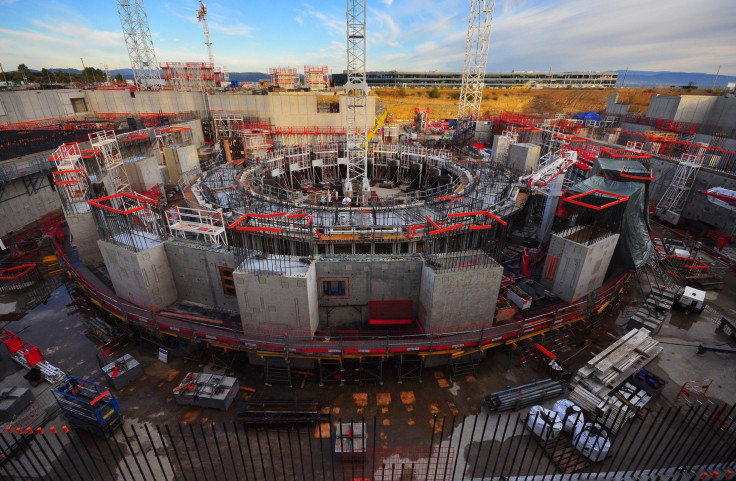

A 200-degree concrete shield is poured at the ITER nuclear fusion facility in Cadarache, France, Oct. 24, 2015. COURTESY OF ITER

Huge hurdles stand in the way of fusion’s promise, however. Right now, fusion reactors require far more electricity to operate than they actually produce, rendering the plants impractical in the real world. Physicists at ITER as well as other government initiatives and private startups are pushing to build more efficient reactors -- a process that will require billions of dollars and no less than a decade to achieve.

Yet breakthrough energy technologies are critical to helping countries drastically and quickly reduce their emissions. In Paris this month, leaders from nearly 200 nations are meeting to negotiate a global climate change agreement, one that will require the world to scale back the use of fossil fuels and switch to lower-carbon alternatives. If they don’t, the planet could face catastrophic levels of global warming, with entire coastlines sinking underwater, violent storms growing more frequent and brutal weather patterns attacking crops and water supplies, according to climate scientists.

The ITER project in Cadarache sits roughly 425 miles south of the United Nations-led climate conference in Paris. There, scientists from Europe, the U.S., Russia, India, China, Japan and South Korea, are attempting to build a 500-megawatt fusion plant, about the size of a typical U.S. coal-fired facility. The $14 billion project includes a 200-foot-high machine called a “tokamak,” which uses massive magnets -- each powerful enough to lift an aircraft carrier -- to contain and fuse doughnut-shaped clouds of hydrogen as they spin.

In nuclear fusion, two hydrogen nuclei are smashed together so tightly that they form a single, larger helium atom. The process releases tremendous amounts of energy. On the sun, fusion creates the sunlight that reaches Earth. In a power plant, the energy is transformed into heat, which produces steam to drive turbines and generate electricity. Hydrogen isn’t mined from the ground; it’s found in places like the ocean’s infinite waters.

Fusion is considered cleaner and safer than nuclear fission, which powers conventional reactors and supplies about 20 percent of U.S. electricity. Fission splits, rather than merges, atoms into fragments, releasing neutrons at high speeds and producing radioactive waste. When the fission process accelerates out of operators’ control, it can result in nuclear meltdowns, like the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi disaster in Japan. Fusion, by contrast, stops as soon as operators turn off the machine.

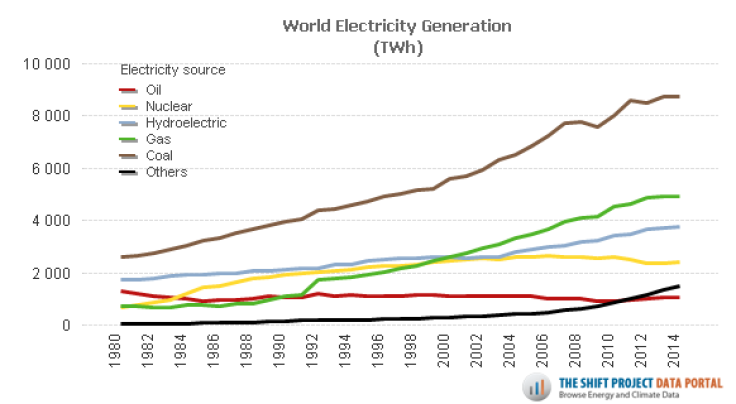

World electricity generation in terrawatt-hours (TWh), 1980-2014. THE WORLD BANK - WORLD DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS

For fusion scientists, the biggest conundrum is how to make hydrogen hot and dense enough to create sustained reactions that will produce vast amounts of power. At ITER, the goal is to build a plant that generates 10 times more electricity than it consumes. Currently, the most efficient reactors still burn twice as much electricity as they produce.

“We’re no longer talking about a purely scientific problem, but an engineering problem,” said Laban Coblentz, ITER’s head of communications, who moved to France this year from New York.

The dilemma is drawing investor-backed startups into the fusion field.

General Fusion, a 13-year-old startup in Vancouver, Canada, is building a reactor that will combine two prominent fusion technologies: the magnet system used in ITER, and “inertial confinement fusion,” which involves firing dozens of giant lasers at a container holding hydrogen to compress and fuse it. “We’re trying to move away from those two extremes and into somewhere in the middle, using common industrial technologies” said Michael Delage, vice president for strategy at General Fusion.

The company has raised around $100 million (Canadian, $76.3 million U.S.), about 80 percent of which comes from private investors including Amazon.com founder Jeffrey Bezos and Chrysalix Energy, a Canadian cleantech venture capital firm. Other fusion startups include Helion Energy, based near Seattle, and Tri Alpha Energy in Orange County, California. Industrial giants are also entering the fray: Lockheed Martin last year announced its own fusion project under its advanced technology arm, Skunk Works.

A scaled-down prototype of General Fusion's "magnetized target fusion" system is seen at the company's facility in Vancouver, Canada. COURTESY OF GENERAL FUSION

General Fusion aims to build pilot and demonstration plants in the next few years and scale up to a commercial power plant within a decade. But Delage hesitated to put the projects on a firm timeline. “The reality is, this is more of a game of making progress foot-by-foot-by-foot, as opposed to ‘Eureka!’ moments where there are huge leaps forward,” he said.

No project embodies this struggle more than ITER. The international effort launched in 1985 after former U.S. President Ronald Reagan and Mikhail Gorbachev, the last leader of the Soviet Union, sought to forge a peaceful collaboration around fusion energy. Three decades and billions of dollars later, the ITER team said last month it expected significant delays and cost overruns, with the first construction milestones not likely to be reached until after 2022.

Still, supporters of developing nuclear fusion say the setbacks don’t dull their hopes the technology one day will transform the global energy sector into a carbon-free, limitless supply of power. “It’s a matter of when, not whether it will happen,” said Edward Morse, a nuclear physicist at the University of California, Berkeley.

https://www.ibtimes.com/paris-climate-talks-nuclear-fusion-holy-grail-clean-energy-technology-2208495 |

|

|

|

|

ITER

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Coordinates:  43.70831°N 5.77741°E 43.70831°N 5.77741°E

ITER

Small-scale model of ITER

|

| Device type |

Tokamak |

| Location |

Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, France |

| Major radius |

6.2 m (20 ft) |

| Plasma volume |

840 m3 |

| Magnetic field |

11.8 T (peak toroidal field on coil)

5.3 T (toroidal field on axis)

6 T (peak poloidal field on coil) |

| Heating power |

320 MW (electrical input)

50 MW (thermal absorbed) |

| Fusion power |

0 MW (electrical generation)

500 MW (thermal from fusion) |

| Discharge duration |

up to 1000 s |

| Date(s) of construction |

2013–2025 |

ITER (initially the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor, iter meaning "the way" or "the path" in Latin[2][3][4]) is an international nuclear fusion research and engineering megaproject aimed at creating energy by replicating, on Earth, the fusion processes of the Sun. Upon completion of construction of the main reactor and first plasma, planned for late 2025,[5] it will be the world's largest magnetic confinement plasma physics experiment and the largest experimental tokamak nuclear fusion reactor. It is being built next to the Cadarache facility in southern France.[6][7] ITER will be the largest of more than 100 fusion reactors built since the 1950s, with ten times the plasma volume of any other tokamak operating today.[8][9]

The long-term goal of fusion research is to generate electricity. ITER's stated purpose is scientific research, and technological demonstration of a large fusion reactor, without electricity generation.[10][8] ITER's goals are to achieve enough fusion to produce 10 times as much thermal output power as thermal power absorbed by the plasma for short time periods; to demonstrate and test technologies that would be needed to operate a fusion power plant including cryogenics, heating, control and diagnostics systems, and remote maintenance; to achieve and learn from a burning plasma; to test tritium breeding; and to demonstrate the safety of a fusion plant.[9][7]

ITER's thermonuclear fusion reactor will use over 300 MW of electrical power to cause the plasma to absorb 50 MW of thermal power, creating 500 MW of heat from fusion for periods of 400 to 600 seconds.[11] This would mean a ten-fold gain of plasma heating power (Q), as measured by heating input to thermal output, or Q ≥ 10.[12] As of 2021, the record for energy production using nuclear fusion is held by the National Ignition Facility reactor, which achieved a Q of 0.70 in August 2021.[13] Beyond just heating the plasma, the total electricity consumed by the reactor and facilities will range from 110 MW up to 620 MW peak for 30-second periods during plasma operation.[14] As a research reactor, the heat energy generated will not be converted to electricity, but simply vented.[7][15][16]

ITER is funded and run by seven member parties: China, the European Union, India, Japan, Russia, South Korea and the United States. The United Kingdom participates through EU's Fusion for Energy (F4E), Switzerland participates through Euratom and F4E, and the project has cooperation agreements with Australia, Canada, Kazakhstan and Thailand.[17]

Construction of the ITER complex in France started in 2013,[18] and assembly of the tokamak began in 2020.[19] The initial budget was close to €6 billion, but the total price of construction and operations is projected to be from €18 to €22 billion;[20][21] other estimates place the total cost between $45 billion and $65 billion, though these figures are disputed by ITER.[22][23] Regardless of the final cost, ITER has already been described as the most expensive science experiment of all time,[24] the most complicated engineering project in human history,[25] and one of the most ambitious human collaborations since the development of the International Space Station (€100 billion or $150 billion budget) and the Large Hadron Collider (€7.5 billion budget).[note 1][26][27]

ITER's planned successor, the EUROfusion-led DEMO, is expected to be one of the first fusion reactors to produce electricity in an experimental environment.[28]

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

72 a 86 de 131

Siguiente Anterior

72 a 86 de 131

Siguiente Último

Último

|

En la fusión por confinamiento magnético, el combustible se comprime mediante campos magnéticos mientras se calienta. Foto: EUROfusion

En la fusión por confinamiento magnético, el combustible se comprime mediante campos magnéticos mientras se calienta. Foto: EUROfusion La energía de fusión es inagotable, limpia y barata. Se basa en la fusión de núcleos ligeros como el hidrógeno, deuterio y tritio. Imagen: brgfx / Freepik

La energía de fusión es inagotable, limpia y barata. Se basa en la fusión de núcleos ligeros como el hidrógeno, deuterio y tritio. Imagen: brgfx / Freepik La energía de fusión es la que se produce en el interior del Sol y las estrellas.

La energía de fusión es la que se produce en el interior del Sol y las estrellas.

![Blog Wars] El DeLorean de Regreso al Futuro: La máquina del tiempo definitiva - Fancueva](http://fancueva.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/09/delorean3.jpg)

/cloudfront-eu-central-1.images.arcpublishing.com/prisa/7EIGHO6T3FDAZKFGWDYTSIUAAI.JPG)