Ernest Lawrence invented the cyclotron, for which he was awarded the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physics. Cyclotrons in his laboratories were used to discover a large number of new chemical elements and isotopes – millions of lives have been saved using these radioisotopes. Lawrence’s work initiated the age of “big science.”

Beginnings

Ernest Orlando Lawrence was born on August 8, 1901 into a middle-class family in the small prairie-town of Canton, South Dakota, USA. His father was Carl Gustavus Lawrence, a superintendent of schools and history teacher. His mother was Gunda Regina Jacobson, a mathematics teacher. Both were of Norwegian ancestry.

Ernest attended elementary and high school in Canton, except for four years spent in South Dakota’s capital, Pierre. The family moved to Pierre because his father’s job took them there when Ernest was aged 9 – 13. Ernest was tall and thin, and he picked up the nickname ‘skinny,’ which he didn’t mind.

Ernest became a seriously knowledgeable radio-ham. He built a shortwave transmitter and shared his enthusiasm for wireless communications with two rather remarkable friends. One was his junior brother John, who became one of the founders of nuclear medicine; the other was Merle Tuve, whose forebears were also Norwegian, and who became a very eminent physicist.

Ernest’s parents were rather devout members of the Lutheran Church. His mother was vehemently opposed to her son to going to the state university, fearing he might be led astray there! He enrolled in medicine at the University of South Dakota in Vermillion in 1919 without his mother’s knowledge. Although a medical student, his passion for building radio transmitters did not slacken. He approached Lewis Akeley, the Dean of Engineering, about setting up a campus radio station.

Akeley, who had once been a professor of chemistry and physics, was so impressed by the young radio enthusiast’s expertise in electronics that he persuaded him to forget about premedical studies and switch to physical sciences instead. So Ernest majored in physical science. And he also started South Dakota’s first ever radio station!

“On the wall of Lawrence’s office, Dean Akeley’s picture always had the place of honor in a gallery that included photographs of Lawrence’s scientific heroes: Arthur Compton, Niels Bohr, and Ernest Rutherford.”

“On the wall of Lawrence’s office, Dean Akeley’s picture always had the place of honor in a gallery that included photographs of Lawrence’s scientific heroes: Arthur Compton, Niels Bohr, and Ernest Rutherford.”

Ernest Lawrence graduated at age 21 with a Bachelor’s Degree, then joined his childhood friend Merle Tuve at the University of Minnesota, where he completed a Master’s Degree in Physics in two years. In 1925 he obtained his Ph.D. in Physics from Yale University.

Ernest Lawrence’s Contributions to Science

The Cyclotron

Alpha-particle bombardments

By 1929 Lawrence had been an associate professor of physics at the University of California at Berkeley for a year.

Until then, physicists used radioactive elements as a source of high energy particles. Alpha-particles, escaping at high speeds from radioactive nuclei, offered scientists like Ernest Rutherford a way to bombard chemical elements with high energy atom-sized particles. This had led to a number of groundbreaking discoveries, including the discoveries of the proton and the atomic nucleus.

Particle Accelerators

In 1929 Lawrence picked up a copy of a science journal to read during a particularly tedious meeting he had to attend. The journal included a paper by Rolf Widerøe, one of the pioneers of a new concept in physics – particle accelerators, or atom-smashers.

Particle accelerators promised scientists a way of using electricity to produce atom-sized particles moving at high speeds. Unlike radioactive sources of particles, the amount of energy carried by particles from accelerators could be fine-tuned to produce specific results.

This was an especially exciting field, because it seemed certain that momentous new discoveries would emerge from the use of accelerators.

Accelerated particles could be crashed into target atoms, producing debris from which information about the tiny, unseen world of the atomic nucleus could be obtained. Also, it was possible that new types of atoms and chemical elements could be produced.

Rolf Widerøe had envisioned a device in which high voltages would be used to accelerate particles in a straight line.

Miniaturizing an Accelerator

Lawrence thought that, if it were to produce very high energy particles, Widerøe’s device would be too long to fit in a typical laboratory.

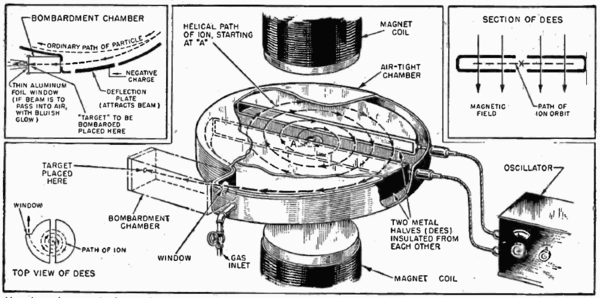

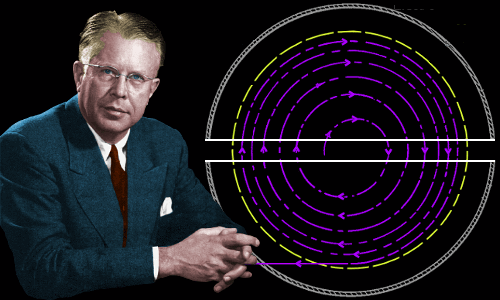

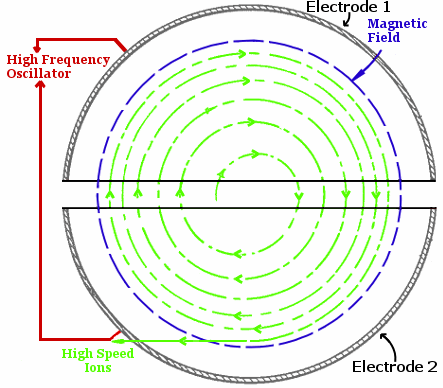

And he instantly had his big idea: instead of accelerating particles in a straight line, he would use electromagnets to accelerate them in a spiral path, gathering ever more speed and energy until they smashed into their target. His device would be smaller and cheaper than Widerøe’s.

Diagram from Lawrence’s cyclotron patent. Charged particles are injected into the center of the cylinder and are accelerated by a high frequency alternating voltage. Magnets above and below the cylinder create the magnetic field that causes the particles to follow a spiral path. While moving in a spiral, the particles repeatedly encounter the accelerating voltage from the electrodes and so are repeatedly accelerated. The elegant result is that the amount of energy given to the particles is many times greater than they would get from following a straight line path with a single applied voltage. Particles spiral outward at ever greater speeds until they crash into a target.

The first cyclotron Lawrence built was only 4 inches (10 cm) across and cost $25. And it worked! It accelerated ions of hydrogen molecules to an energy of 80,000 electron volts.

It is ironic that Lawrence’s big idea was for low-cost miniaturization of an accelerator. Soon enough, he would be the pacesetter in high-cost “big science.”

Ever Bigger

Lawrence saw the great potential of his device, and others did too – he now got funding to develop both linear accelerators and cyclotrons. He was thrilled with how things had turned out. His work allowed him to revisit those idyllic, happy, childhood days of building wireless transmitters with sympathetic friends. Except now he could indulge his passion for electronic equipment on an epic scale.

And the icing on the cake was that at 29 years old, he was promoted to become the University of California’s youngest full professor.

By mid-1931 he had an 11-inch cyclotron operating using a 2 ton magnet and was planning a 27-inch cyclotron using an 80 ton magnet!

Lawrence’s cyclotron patent was granted in 1934. Although he’d patented the device, he encouraged other research laboratories to build cyclotrons, gave them assistance when they got stuck, and never charged any royalties for his invention. He was also generous with new radioactive materials produced in his laboratory, giving samples to other laboratories to help them out.

Albert Einstein, however, had reservations about the usefulness of research using particle accelerators, declaring:

“You see, it is like shooting birds in the dark in a country where there are only a few birds.”

“You see, it is like shooting birds in the dark in a country where there are only a few birds.”

Since atoms are mainly empty space, Einstein was correct in his analogy. What he overlooked is the fact that accelerators would soon reach a point where they had a very rapid rate of fire and a virtually unlimited supply of bullets!

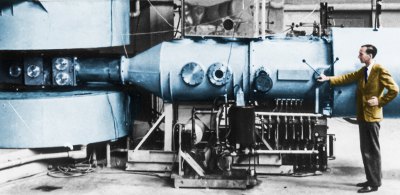

The 60-inch cyclotron, completed in 1939, at the Lawrence Radiation Laboratory, Berkeley. This device features two magnets weighing a total of almost 200 tons. Glenn Seaborg and his coworkers used this particle accelerator to discover five new chemical elements: plutonium, curium, americium, berkelium, and californium.

Lawrence provided scientists with the finest ever tool for discovering the secrets of the atom. Scientists like Glenn Seaborg and Albert Ghiorso would use Berkeley’s cyclotrons to greatly expand the number of elements in the periodic table.

“His cyclotron is to nuclear science what Galileo’s telescope was to astronomy … his buoyant optimism spread to everyone around him and accounted for the attainment of many an ‘impossible’ objective.”

“His cyclotron is to nuclear science what Galileo’s telescope was to astronomy … his buoyant optimism spread to everyone around him and accounted for the attainment of many an ‘impossible’ objective.”

Missing out on Discoveries

In the early 1930s Lawrence and his growing team, although making great efforts to make new discoveries using their cyclotrons, were not very successful.

- They could have discovered transmutation of lithium to helium by proton bombardment, but didn’t. This ‘splitting of the atom’ was discovered in 1932 by John Cockcroft and Ernest Walton, at the University of Cambridge in the UK, for which the pair received the 1951 Nobel Prize in physics.

- They could have discovered nuclear fusion, but didn’t. This was discovered in 1934 by Ernest Rutherford and Mark Oliphant, also at the University of Cambridge in the UK. Oliphant used a particle accelerator to fire deuterium ions at substances such as ammonium chloride and found he had produced helium-3 and tritium. (In fact, Lawrence’s team in Berkeley had carried out a similar experiment but had – to Lawrence’s ultimate considerable embarrassment – misinterpreted the results, wrongly believing they had discovered that deuterons disintegrate.)

- They could have discovered how to synthesize artificial radioactive elements by alpha-particle bombardment, but didn’t. This was discovered in 1934 by the Joliot-Curies at the Curie Institute in Paris, France, for which they received the 1935 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Lawrence was particularly dismayed when he heard about this, because he realized it was something his own laboratory could have achieved easily.

“We have had these radioactive substances in our midst for more than half a year. We have been kicking ourselves that we haven’t had the sense to notice that the radiations given off do not stop immediately after turning off the bombarding beam.”

“We have had these radioactive substances in our midst for more than half a year. We have been kicking ourselves that we haven’t had the sense to notice that the radiations given off do not stop immediately after turning off the bombarding beam.”

Although it was maddening to have missed out on some incredibly exciting discoveries, Lawrence was not fazed. His greatest ambition was to build ever more powerful accelerators, because he felt that ultimately these accelerators would yield secrets of nature not available at lower energies.

“I have gotten over feeling badly. We would be eternally miserable if our errors worried us too much because as we push forward we will make plenty more.”

“I have gotten over feeling badly. We would be eternally miserable if our errors worried us too much because as we push forward we will make plenty more.”

And discoveries did begin to flow using Lawrence’s cyclotrons. In 1939 Luis Alvarez and Robert Cornog used the 60-inch cyclotron to study helium-3. Theoreticians had said helium-3 would be radioactive. Actually, it proved to be stable. And then Alvarez and Cornog used the 37-inch cyclotron to produce tritium, which theoreticians said would be stable, but was actually radioactive. In the same year, Edwin McMillan and Philip Abelson used the 60-inch cyclotron to produce and so discover the new element neptunium. Many more discoveries would follow.

Cancer Treatments

Lawrence’s cyclotrons were soon making a difference to people’s lives. In 1921 the American people had raised $100,000 for Marie Curie to purchase a mere 1 gram of radium for research and cancer treatments. Radioactive elements for cancer treatments were shockingly expensive.

With his cyclotron, Lawrence realized he could fine-tune the production of radioactive isotopes.

In 1934 he realized that sodium-24 could be an ideal, non-toxic source of gamma rays for cancer radiotherapy. He used one of his cyclotrons to convert normal rock salt into sodium-24 by deuteron bombardment. Soon, for about $2 worth of salt and power, he had made the medical equivalent of radium that had cost $100,000 in 1921!

Lawrence continued his efforts to make radioisotopes for cancer therapy. While carrying out this work researchers in his laboratory discovered carbon-14, oxygen-15, fluorine-18, and thallium-201.

Technetium-99m, now used worldwide in tens of millions of medical procedures every year, was also discovered in his laboratory. Technetium-99m’s use has saved millions of lives.

Keeping it in the Family

In 1936 Lawrence invited his brother John, from Yale University’s medical faculty, to Berkeley to cooperate in trials using the cyclotron and its products in medical treatments. The result was huge success, to the extent that John Lawrence is now known as the father of nuclear medicine.

In 1937 Lawrence’s mother was diagnosed with inoperable cancer and given just a few months to live. Ernest and John decided to attack her tumor using an incredibly powerful x-ray machine that Ernest and his team had built and installed at the University of California’s medical school. The result was that his mother was completely cured. She actually went on to outlive Ernest.

Cyclotrons and Cancer Today

In addition to producing radioisotopes for cancer treatments, cyclotrons are still in use today producing proton beams, which yield neutron beams, which are used to attack cancers directly.

The Nobel Prize

Ernest Lawrence was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1939 for his invention of the cyclotron and the discoveries made with it. He and his team conquered a huge number of colossal engineering problems to achieve their results.

“The important ingredients of his success were native ingenuity and basic good judgment in science, great stamina, an enthusiastic and outgoing personality, and a sense of integrity that was overwhelming.”

“The important ingredients of his success were native ingenuity and basic good judgment in science, great stamina, an enthusiastic and outgoing personality, and a sense of integrity that was overwhelming.”

Ever Bigger Science and the Bomb

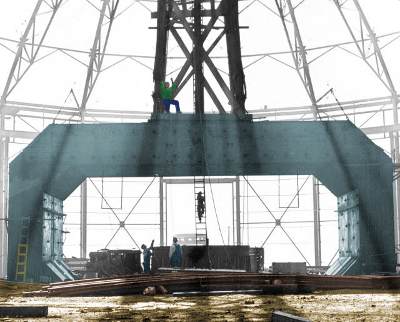

By 1940 Lawrence was planning a 184-inch cyclotron, which needed 4500 tons of magnets. The Rockefeller Foundation put up over a million dollars to get the project started. Lawrence’s research was growing fast in scale and ambition. It had become big science.

It is a testament to Lawrence’s energy and persuasive skills that he was able find funding. He was helped by the fact that governments around the world were becoming increasingly interested in releasing the enormous amount of energy scientists had realized was present in the atomic nucleus.

Lawrence’s 184-inch cyclotron during construction. The era of big science had begun.

With the world’s most advanced accelerators and the discovery in 1940 of plutonium using the Berkeley 60-inch cyclotron, Lawrence was destined to play a leading role in the Manhattan Project – the project that built the world’s first nuclear weapon and would push science to ever greater scales of operation.

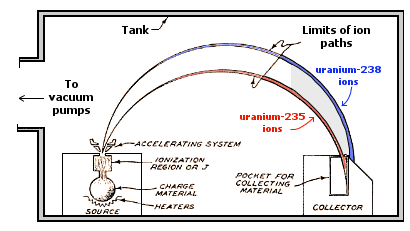

Lawrence developed a new device, the calutron, to separate isotopes of uranium. The calutron was a hybrid of the cyclotron and a mass spectrometer. Calutrons were employed to produce the uranium-235 that was used in the Little Boy atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in August 1945.

Lawrence’s calutron invention was used to separate isotopes of uranium.

“The atomic bombs will surely shorten the war, and let us hope that they will effectively end war as a possibility in human affairs.”

“The atomic bombs will surely shorten the war, and let us hope that they will effectively end war as a possibility in human affairs.”

The largest cyclotron Lawrence built for research purposes was the 184-inch (4.67 meter) cyclotron completed in 1942. Protons could be accelerated to energies in excess of 100 MeV.

Today, the age of big science that began with Lawrence marches onward. Ever bigger, ever more expensive, ever more powerful devices continue to reveal the extent and depth of the subatomic world.

In 2015, CERN’s Large Hadron Collider operated in a circular tunnel almost 17 miles (27,000 meters) long underneath Switzerland. Particle energies reached 6.5 TeV – about 65,000 times more powerful than Lawrence’s 1942 device.

Some Personal Details and the End

Lawrence married Mary Kimberly Blumer in May 1932. The daughter of the Dean of Yale’s Medical School, she was always known as Molly. Molly had a Bachelor’s Degree in Bacteriology and met her future husband on a blind date. The couple had six children.

Ernest Lawrence died at the age of 57 on August 27, 1958 in a hospital in Palo Alto, California following surgery for intestinal problems.

Less than a month after his death, the University of California renamed two of the university’s nuclear research laboratories in his honor: the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Today both continue as world-leading research centers.

Three years after his death, element 103 was discovered, produced for the first time in a particle accelerator at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The element was named lawrencium in honor of the man who had made its discovery possible.

Author of this page: The Doc

Images digitally enhanced and colorized by this website. © All rights reserved.

Cite this Page

Please use the following MLA compliant citation:

"Ernest Lawrence." Famous Scientists. famousscientists.org. 24 Oct. 2015. Web. 8/8/2024.

Published by FamousScientists.org

Further Reading

Glenn Seaborg

E. O. Lawrence – Physicist, Engineer, Statesman of Science.

Science, 128 (3332), p1123-1124, Nov 7 1958

Luis W. Alvarez

Ernest Orlando Lawrence – A Biographical Memoir

National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C., 1970

J. L. Heilbron, Robert W. Seidel

Lawrence and His Laboratory: A History of the Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, Volume 1

University of California Press, 1989

Jeffrey E. Williams

Donner Laboratory: The Birthplace of Nuclear Medicine

Nucl Med., 40:16N-20N, 1999

Science and Technology Review

Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, 2001

Paul Halpern

Collider: The Search for the World’s Smallest Particles

John Wiley & Sons, 2009

Michael Hiltzik

Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention that Launched the Military-Industrial Complex

Simon and Schuster, 2015