A service in a Spanish

synagogue, from the

Sister Haggadah (c. 1350). The Alhambra Decree would bring Spanish Jewish life to a sudden end.

The Alhambra Decree (also known as the Edict of Expulsion; Spanish: Decreto de la Alhambra, Edicto de Granada) was an edict issued on 31 March 1492, by the joint Catholic Monarchs of Spain (Isabella I of Castile and Ferdinand II of Aragon) ordering the expulsion of practising Jews from the Crowns of Castile and Aragon and its territories and possessions by 31 July of that year.[1] The primary purpose was to eliminate the influence of practising Jews on Spain's large formerly-Jewish converso New Christian population, to ensure the latter and their descendants did not revert to Judaism. Over half of Spain's Jews had converted as a result of the religious persecution and pogroms which occurred in 1391.[2] Due to continuing attacks, around 50,000 more had converted by 1415.[3] A further number of those remaining chose to convert to avoid expulsion. As a result of the Alhambra decree and persecution in the years leading up to the expulsion of Spain's estimated 300,000 Jewish origin population, a total of over 200,000 had converted to Catholicism to remain in Spain, and between 40,000 and 100,000 remained Jewish and suffered expulsion. An unknown number of the expelled eventually succumbed to the pressures of life in exile away from formerly-Jewish relatives and networks back in Spain, and so converted to Catholicism to be allowed to return in the years following expulsion.[4]:17

In 1924, the regime of Primo de Rivera granted Spanish citizenship to a part of the Sephardic Jewish diaspora, though few people benefited from it in practice.[5] The decree was then formally and symbolically revoked on 16 December 1968 by the regime of Francisco Franco,[6] following the Second Vatican Council. This was a full century after Jews had been openly practising their religion in Spain and synagogues were once more legal places of worship under Spain's Laws of Religious Freedom.

In 2015, the government of Spain passed a law allowing dual citizenship to Jewish descendants who apply, to "compensate for shameful events in the country's past."[7] Thus, Sephardi Jews who could prove that they are the descendants of those Jews expelled from Spain because of the Alhambra Decree would "become Spaniards without leaving home or giving up their present nationality."[8][9] The Spanish law[10] expired in 2019 and new applications for Spanish citizenship on the basis of Sephardic family heritage are no longer allowed. However, the descendants of the Jews exiled from the Iberian Peninsula may still apply for Portuguese citizenship.

By the end of the eighth century, Muslim forces had conquered and settled most of the Iberian Peninsula.[3] Under Islamic law, the Jews, who had lived in the region since at least Roman times, were considered "People of the Book," which was a protected status.[11] Compared to the repressive policies of the Visigothic Kingdom, who, starting in the sixth century had enacted a series of anti-Jewish statutes which culminated in their forced conversion and enslavement, the tolerance of the Muslim Moorish rulers of al-Andalus allowed Jewish communities to thrive.[3] Jewish merchants were able to trade freely across the Islamic world, which allowed them to flourish, and made Jewish enclaves in Muslim Iberian cities great centers of learning and commerce.[3] This led to a flowering of Jewish culture, as Jewish scholars were able to gain favor in Muslim courts as skilled physicians, diplomats, translators, and poets. Although Jews never enjoyed equal status to Muslims, in some Taifas, such as Granada, Jewish men were appointed to very high offices, including Grand Vizier.[12]

The Reconquista, or the gradual reconquest of Muslim Iberia by the Christian kingdoms in the North, was driven by a powerful religious motivation: to reclaim Iberia for Christendom following the Umayyad conquest of Hispania centuries before. By the fourteenth century, most of the Iberian Peninsula (present-day Spain and Portugal) had been reconquered by the Christian kingdoms of Castile, Aragon, León, Galicia, Navarre, and Portugal.

During the Christian re-conquest, the Muslim kingdoms in Spain became less welcoming to the dhimmi. In the late twelfth century, the Muslims in al-Andalus invited the fanatical Almohad dynasty from North Africa to push the Christians back to the North.[3] After they gained control of the Iberian Peninsula, the Almohads offered the Jews a choice between expulsion, conversion, and death.[3] Many Jewish people fled to other parts of the Muslim world, and also to the Christian kingdoms, which initially welcomed them. In Christian Spain, Jews functioned as courtiers, government officials, merchants, and moneylenders.[3] Therefore, the Jewish community was both useful to the ruling classes and to an extent protected by them.[13]

As the Reconquista drew to a close, overt hostility against Jews in Christian Spain became more pronounced, finding expression in brutal episodes of violence and oppression. In the early fourteenth century, the Christian kings vied to prove their piety by allowing the clergy to subject the Jewish population to forced sermons and disputations.[3] More deadly attacks came later in the century from mobs of angry Catholics, led by popular preachers, who would storm into the Jewish quarter, destroy synagogues, and break into houses, forcing the inhabitants to choose between conversion and death.[3] Thousands of Jews sought to escape these attacks by converting to Christianity. These Jewish converts were commonly called conversos, New Christians, or marranos; the latter two terms were used as insults. At first, these conversions seemed an effective solution to the cultural conflict: many converso families met with social and commercial success.[3] But eventually their success made these new Catholics unpopular with their neighbors, including some of the clergy of the Church and Spanish aristocrats competing with them for influence over the royal families. By the mid-fifteenth century, the demands of the Old Christians that the Catholic Church and the monarchy differentiate them from the conversos led to the first limpieza de sangre laws, which restricted opportunities for converts.[3]

These suspicions on the part of Christians were only heightened by the fact that some of the conversions were insincere. Some conversos, also known as crypto-Jews, embraced Christianity and underwent baptism while privately adhering to Jewish practices and faith. Recently converted families who continued to intermarry were especially viewed with suspicion.[3] For their part, the Jewish community viewed conversos with compassion, because Jewish law held that conversion under threat of violence was not necessarily legitimate.[3] Although the Catholic Church was also officially opposed to forced conversion, under ecclesiastical law all baptisms were lawful, and once baptized, converts were not allowed to rejoin their former religion.[3]

Expulsions of Jews in Europe from 1100 to 1600

From the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries, European countries expelled the Jews from their territories on at least fifteen occasions. Before the Spanish expulsion, the Jews had been expelled from England in 1290, several times from France between 1182 and 1354, and from some German states. The French case is typical of most expulsions: whether the expulsion was local or national, the Jews usually were allowed to return after a few years.[14] The Spanish expulsion was succeeded by at least five expulsions from other European countries,[15][16] but the expulsion of the Jews from Spain was both the largest of its kind and, officially, the longest lasting in western European history.

Over the four-hundred-year period during which most of these decrees were implemented, the causes of expulsion gradually changed. At first, expulsions of Jews (or absence of expulsions) were exercises of royal prerogatives. Jewish communities in medieval Europe often were protected by and associated with monarchs because, under the feudal system, Jews often were a monarch's only reliable source of taxes.[14] Jews further had reputations as moneylenders because they were the only social group allowed to loan money at a profit under the prevailing interpretation of the Vulgate (the Latin translation of the Bible used in Roman Catholic western Europe as the official text), which forbade Christians to charge interest on loans.[14] Jews, therefore, became the lenders to and creditors of merchants, aristocrats, and even monarchs. Most expulsions before the Alhambra Decree were related to this financial situation: to raise additional monies, a monarch would tax the Jewish community heavily, forcing Jews to call in loans; the monarch then would expel the Jews; at the time of expulsion, the monarch would seize their remaining valuable assets, including debts owed them by other subjects of the monarch and, in some instances, by the monarch himself.[14] Expulsion of the Jews from Spain was thus an innovation not only in scale but also in its motivations.

Ferdinand and Isabella

[edit]

Expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492 by

Emilio Sala Francés

Hostility towards the Jews in Spain was brought to a climax during the reign of the "Catholic Monarchs," Ferdinand and Isabella. Their marriage in 1469, which formed a personal union of the crowns of Aragon and Castile, with coordinated policies between their distinct kingdoms, eventually led to the final unification of Spain.

Although their initial policies towards the Jews were protective, Ferdinand and Isabella were disturbed by reports claiming that most Jewish converts to Christianity were insincere in their conversion.[3] As mentioned above, some claims that conversos continued to practice Judaism in secret (see Crypto-Judaism) were true, but the "Old" Christians exaggerated the scale of the phenomenon. It was also claimed that Jews were trying to draw conversos back into the Jewish fold. In 1478, Ferdinand and Isabella made a formal application to Rome to set up an Inquisition in Castile to investigate these and other suspicions. In 1487, King Ferdinand promoted the establishment of the Spanish Inquisition Tribunals in Castile.[3] In the Crown of Aragon, it had been first instituted in the 13th century to combat the Albigensian heresy. However, the focus of this new Inquisition was to find and punish conversos who were practicing Judaism in secret.[17] [page needed]

These issues came to a head during Ferdinand and Isabella's final conquest of Granada. The independent Islamic Emirate of Granada had been a tributary state to Castile since 1238. Jews and conversos played an important role during this campaign because they had the ability to raise money and acquire weapons through their extensive trade networks.[3] This perceived increase in Jewish influence further infuriated the Old Christians and the hostile elements of the clergy.[3] Finally, in 1491 in preparation for an imminent transition to Castilian territory, the Treaty of Granada was signed by Emir Muhammad XII and the Queen of Castile, protecting the religious freedom of the Muslims there. By 1492, Ferdinand and Isabella had won the Battle of Granada and completed the Catholic Reconquista of the Iberian Peninsula from Islamic forces. However, the Jewish population emerged from the campaign more hated by the populace and less useful to the monarchs.

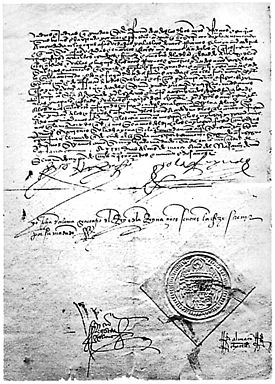

A signed copy of the Edict of Expulsion