|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 1 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

Logo of the bank by John Langdon

The Depository Bank of Zurich is the most hi-tech bank in the world as it interacts with its clients anonymously. It can be found in France at 24 Rue Haxo. It's symbol is a red, equilateral cross. Its official website is part of the Da Vinci Code Webquest.

Founded in 1967, the Depository Bank of Zurich is a twenty-four-hour GeldshrankeBanke offering the full modern array of anonymous services in the tradition of the Swiss numbered account. Maintaining offices in Zurich, Kuala Lumpur, New York, and Paris, the bank has expanded its services in recent years to offer anonymous computer source-code escrow services, faceless digitized backup, and LagernAnonymen— blind drop services. Clients wishing to store anything from stock certificates to valuable paintings can deposit their belongings anonymously, withdrawing items at anytime, also in total anonymity. Clients also have access to 24-hour live video-feeds of the contents of their deposit boxes.

People Involved

Jacques Saunière - former curator of the Louvre Museum. His key has the initials PS on it, which stood for Priory of Sion and Princess Sophie. Inside his box, he has 2 cryptexes, one within another. His password is the Fibonacci Sequence.

André Vernet - president of the bank of Zurich

Robert Langdon - opened Saunière's account upon implied request given at the Louvre at around 11 pm.

Sophie Neveu - was with Robert Langdon.

A message from Bank President, Andre Vernet

The Paris Branch of the Zurich Depository Corp services customers from all over the world. Our discreet staff is accessible around the clock to attend to all of your anonymous depository and banking needs. No matter what asset you have on deposit with us, your trust is our greatest treasure.

Webquest Answers

As mentioned earlier, the website is part of the Da Vinci Code Webquest. For the answer for this particular phase of the quest, type Marie Denarnaud for the name and the fibonacci sequence found in chapter 44 of the Da Vinci Code for the password:

1123581321

More Information

The Depository Bank of Zurich is a fictional Geldschrankbank (secure depository facility) appearing in the 2003 novel Da Vinci Code (Book) The Da Vinci Code by Dan Brown. The address of its Paris branch is 24 rue Haxo, and according to the book, it also has branches in Kuala Lumpur, New York, and Zurich. The president of its Paris branch is André Vernet. The bank allows for 24-hour fully-automated access to anonymous accounts and deposits safe vaults.

Random House, which published The Da Vinci Code, created a mock web site for the bank as part of an advertising campaign for the book. The site includes a "customer" login feature as part of the solution to a contest involving the promotion of the book.

The information above is taken from here.

|

|

|

Primo

Primo

Precedente

2 a 16 di 16

Successivo

Precedente

2 a 16 di 16

Successivo

Ultimo

Ultimo

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 2 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

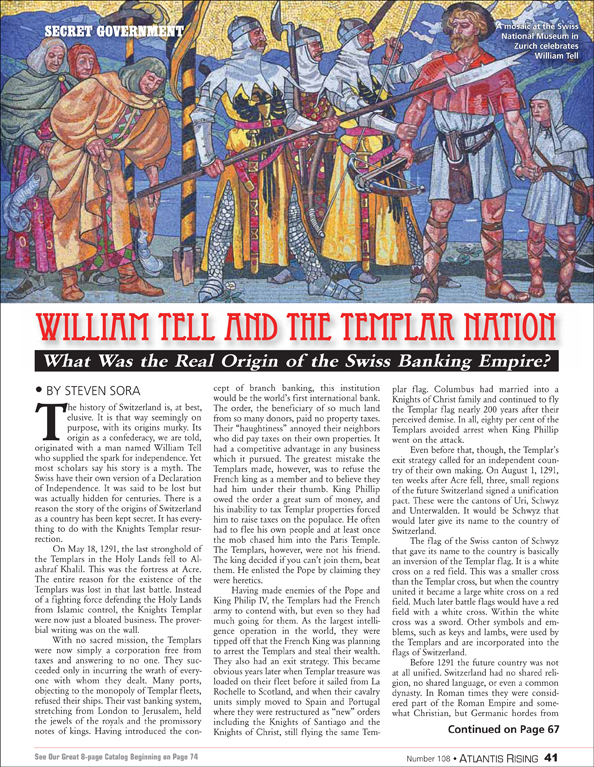

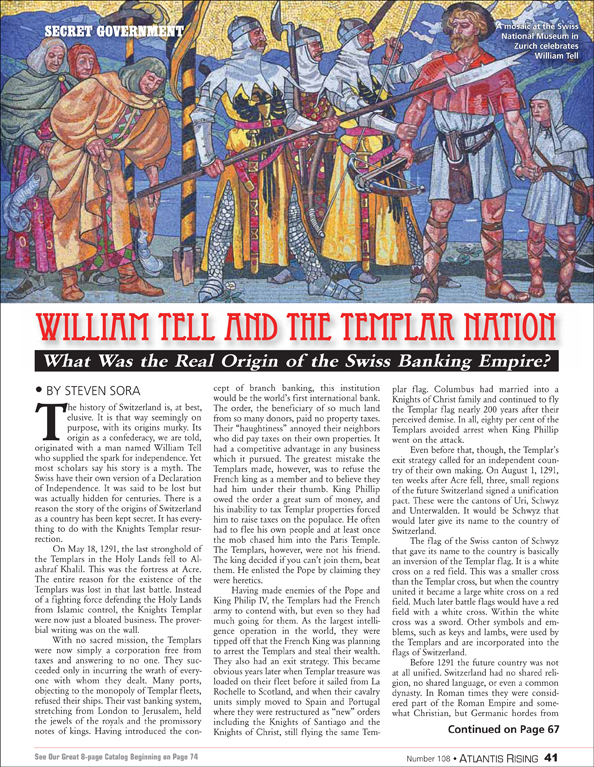

DID THE TEMPLARS REALLY GO OUT OF EXISTENCE?

The history of Switzerland is, at best, elusive. It is that way seemingly on purpose, with its origins murky. Its origin as a confederacy, we are told, originated with a man named William Tell who supplied the spark for independence. Yet most scholars say his story is a myth. The Swiss have their own version of a Declaration of Independence. It was said to be lost but was actually hidden for centuries. There is a reason the story of the origins of Switzerland as a country has been kept secret. It has everything to do with the Knights Templar resurrection.

On May 18, 1291, the last stronghold of the Templars in the Holy Lands fell to Al-ashraf Khalil. This was the fortress at Acre. The entire reason for the existence of the Templars was lost in that last battle. Instead of a fighting force defending the Holy Lands from Islamic control, the Knights Templar were now just a bloated business. The proverbial writing was on the wall.

With no sacred mission, the Templars were now simply a corporation free from taxes and answering to no one. They succeeded only in incurring the wrath of everyone with whom they dealt. Many ports, objecting to the monopoly of Templar fleets, refused their ships. Their vast banking system, stretching from London to Jerusalem, held the jewels of the royals and the promissory notes of kings. Having introduced the concept of branch banking, this institution would be the world’s first international bank. The order, the beneficiary of so much land from so many donors, paid no property taxes. Their “haughtiness” annoyed their neighbors who did pay taxes on their own properties. It had a competitive advantage in any business that it pursued. The greatest mistake the Templars made, however, was to refuse the French king as a member and to believe they had him under their thumb. King Phillip owed the order a great sum of money, and his inability to tax Templar properties forced him to raise taxes on the populace. He often had to flee his own people and at least once the mob chased him into the Paris Temple. The Templars, however, were not his friend. The king decided if you can’t join them, beat them. He enlisted the Pope by claiming they were heretics.

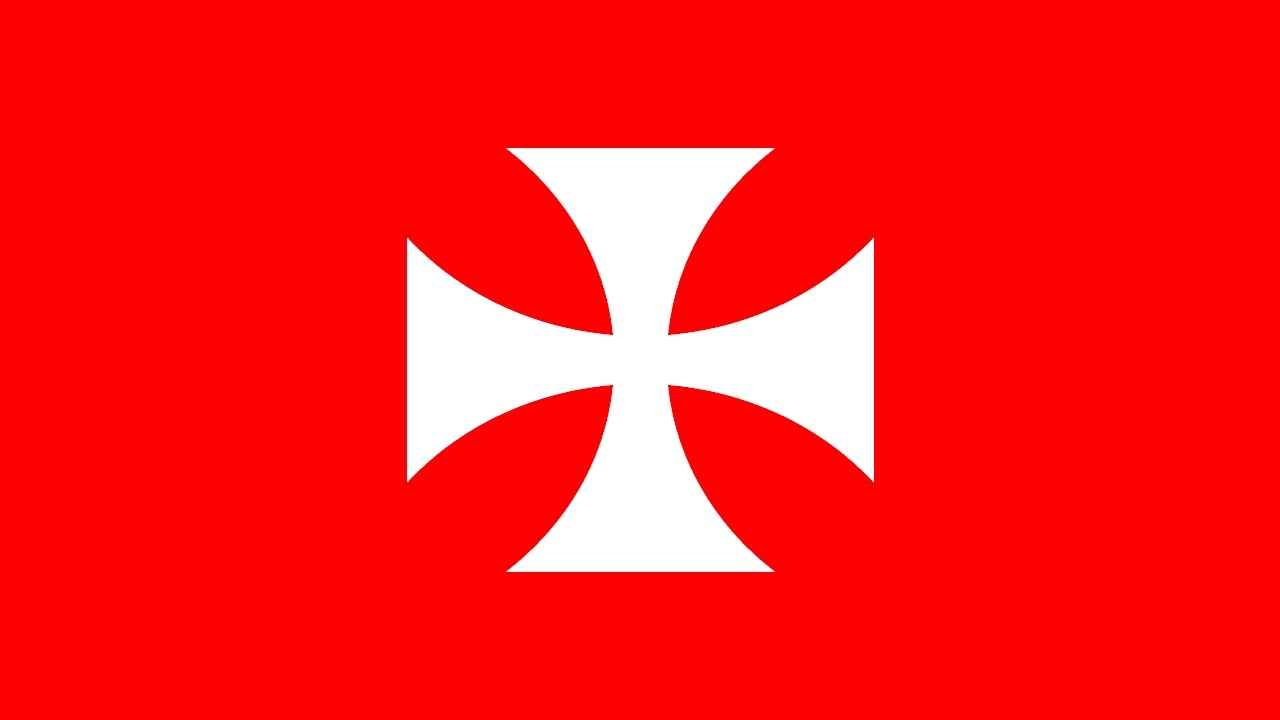

Having made enemies of the Pope and King Philip IV, the Templars had the French army to contend with, but even so they had much going for them. As the largest intelligence operation in the world, they were tipped off that the French King was planning to arrest the Templars and steal their wealth. They also had an exit strategy. This became obvious years later when Templar treasure was loaded on their fleet before it sailed from La Rochelle to Scotland, and when their cavalry units simply moved to Spain and Portugal where they were restructured as “new” orders including the Knights of Santiago and the Knights of Christ, still flying the same Templar flag. Columbus had married into a Knights of Christ family and continued to fly the Templar flag nearly 200 years after their perceived demise. In all, eighty percent of the Templars avoided arrest when King Phillip went on the attack.

Even before that, though, the Templar’s exit strategy called for an independent country of their own making. On August 1, 1291, ten weeks after Acre fell, three, small regions of the future Switzerland signed a unification pact. These were the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. It would be Schwyz that would later give its name to the country of Switzerland.

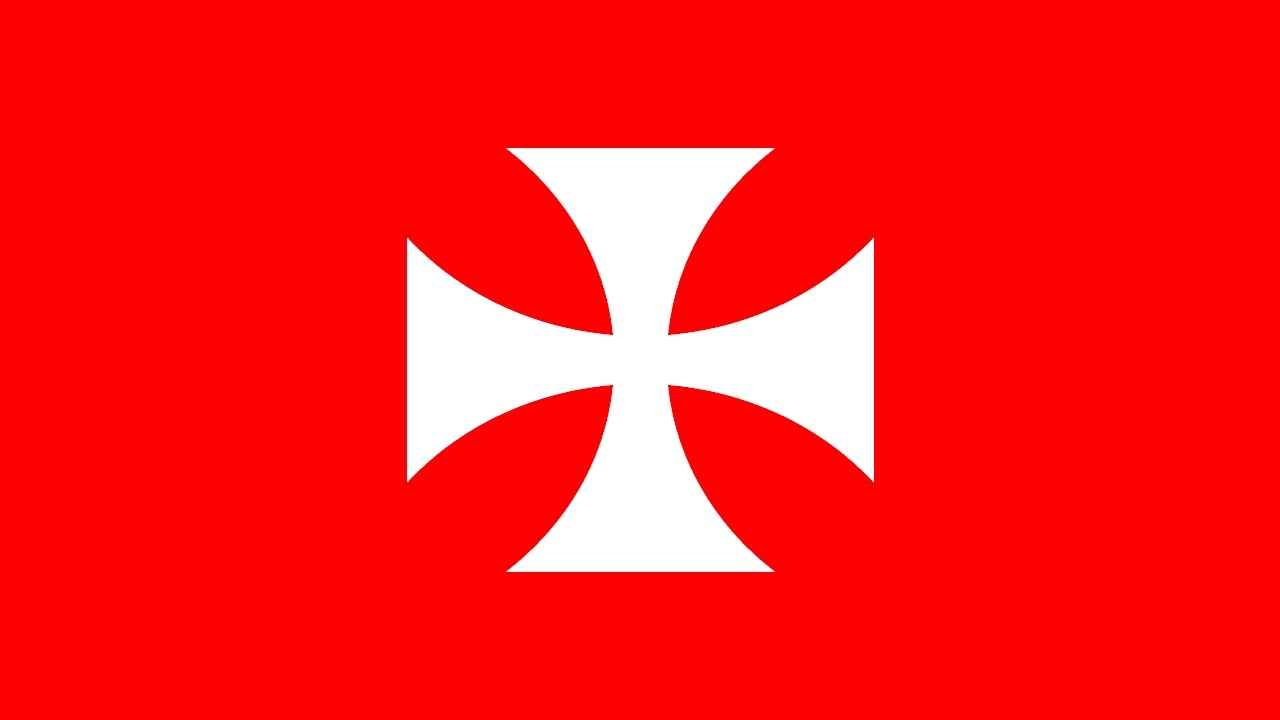

The flag of the Swiss canton of Schwyz that gave its name to the country is basically an inversion of the Templar flag. It is a white cross on a red field. This was a smaller cross than the Templar cross, but when the country united, it became a large white cross on a red field. Much later, battle flags would have a red field with a white cross. Within the white cross was a sword. Other symbols and emblems, such as keys and lambs, were used by the Templars and are incorporated into the flags of Switzerland.

Before 1291, the future country was not at all unified. Switzerland had no shared religion, no shared language, or even a common dynasty. In Roman times they were considered part of the Roman Empire and somewhat Christian, but Germanic hordes from the north brought pagan religion and Germanic language.

As Rome imploded, the territory that would become Switzerland was under a handful of minor family dynasties that mostly came apart. Circa 1300, no one expected the small towns and thinly settled valleys to unite or form cantons or states. The Holy Roman Empire decided these were its property but asked only for taxes. Modern historians concur there was no such thing as Swiss, or Switzerland, before 1400.

Birth of the Templar Nation

That changed in 1291 when a document known as the Bundesbrief united Uri Schwyz and Unterwalden. Representatives would convene at a mountain meadow on Lake Lucerne. The forest cantons, as they were known, would sign a compact of mutual assistance. Folktales record the white-coated, red-crossed knights that pledged assistance to the Swiss Confederacy as it would be known. The document itself was like the American Declaration of Independence, and while it might be expected to have been regarded as sacred; it wasn’t. Instead it was simply lost until the nineteenth century. Or at least kept secret. Then when the expected assault on the Templar existence finally came the Templars were ready.

On Oct 13, 1307, the command went out to arrest the Knights Templar. That day and in the weeks to follow, 600 out of 3000 knights in France were arrested. These were just knights. Each had a retinue of squires, servants, and aides who were not arrested. So, the Templar organization still had thousands who were not apprehended. Some had been traveling regularly through the Alps to Switzerland, which had once been a province of the Merovingian kings and where the small city of Sion once held the Merovingian mint.

Swiss Alpine passes and its central location brought trade through the country and allowed craftsmen access to markets outside of their country. Trade fairs and markets from these times always had compliant bankers and moneylenders who would assist merchants. Similarities between the Templar invention of international banking and Switzerland’s leading role in banking today are no coincidence.

Just how many Templar knights entered Switzerland would not be known. The Hapsburg family “controlled” Swiss cantons and did not allow anyone to challenge their ability to tax the cantons. They allowed the cantons to rule themselves in law and custom as long as they paid their taxes. The Templars, however, had existed for nearly 200 years without paying taxes. Unfortunately, the Swiss, noted for their secrecy, either know little of their early history or deliberately claim not to know.

William Tell and Swiss Independence

The story of William Tell may be a cover tale for the new challenge to the Hapsburg establishment. It is said to be a myth, but unlike myths that begin with nebulous timeframes, the William Tell story begins with an exact date. On November 18, 1307, William Tell visited the town of Altdorf with his son. This was five weeks after the Templars fled France ahead of their arrests. Altdorf was a municipality of Uri, one of the first three cantons to unite shortly after the Templar loss of Acre. He met with and offended Albrecht Gessler, who is the “Vogt,” a nominal bureaucrat appointed by the Habsburgs. The Vogt had hung his hat in the center of town and declared everyone who passed the hat had to bow to it. Tell passed by and publicly refused to bow. Gessler wanted to arrest the stranger but instead challenged him to shoot an apple off his son’s head with an arrow. Tell accomplished the dangerous challenge and Gessler commented that he still held another arrow. Tell’s answer was that it was for killing Gessler if he missed. The outcome was that Tell killed Gessler. His arrow struck a blow for liberty igniting the cantons against their Hapsburg overlords. Tell played a leading role in the rebellion that followed. In 1307–1308 many forts of the Hapsburgs were destroyed and this, in effect, united others and finally brought about the Swiss Confederation. Tell himself was declared the “first confederate” in a song of his exploits.

The Scots Guard and the Swiss Guard

Possibly the largest contingent of fleeing Templars went into the welcoming arms of Scotland. In Scotland, Robert Bruce had challenged the power of the King of England and declared Scotland’s independence. The English army would ride north and meet the Scots at Bannockburn. Just as it appeared the Scots were beaten, a fresh force of Templar Knights rode into battle and turned the tide. It was June 24, 1314, the feast of St. John Baptist, a most sacred day to the Templars. Soon afterwards the Scots Guard became a military force for hire.

In Switzerland, the Swiss cantons decided not to pay the feudal taxes imposed on them. The Hapsburg dukes were not simply going away though. In 1315, just one year after Bannockburn, the dukes sent an army to enforce the feudal dues. As with the English invasion of Scotland, the Hapsburgs thought the tiny cantons had no chance of resisting their army. But, like the English at Bannockburn, the Hapsburgs were not ready for the army they faced. In the Pass of Morgarten, the infantry of Uri and Schwyz defeated the Austrian cavalry in what became known as “the Marathon of Switzerland.” Like the Scottish victory at Bannockburn, the Swiss fought and defeated a larger enemy. No doubt incorporating ex-Templars as well as their training and support, the Swiss would form the Swiss Guard. It was also a mercenary force that could be leased out only with the approval of the Guard, not by the whims of a king. Ironically the Swiss Guard would be hired to defend the Vatican.

The Pontifical Swiss Guard had their origins in the fifteenth century when Pope Sixtus IV made an alliance with the Swiss Confederation. History shows their independence in not always fighting for one country. They fought for France against Naples, and both for and against the Holy Roman Empire. Their bravery, however, was never in question. Like the Templars, they never fled from greater odds. On May 6, 1527, 189 Swiss Guards fought a rear-guard action against the Holy Roman Empire. While 40 guard members helped Pope Clement VII escape, 147 of the 189 died, including their commander.

The Swiss Confederation grew with the addition of Zurich, Bern, Lucerne and Zug. While it had a strong fighting force, it declared its neutrality. It would take another two centuries to complete the formation of what became Switzerland. By becoming a neutral nation they were possibly protecting themselves from the Catholic France and Catholic Austria to the west and east. They were not always neutral, however, and had taken Lugano and other Italian properties while Italy was still a disrupted state. Oddly enough, in a very Protestant country, the Swiss Guard is made up of Swiss male citizens who are trained in the Swiss military and practice the Catholic religion.

It is no coincidence that the modern Red Cross also was born in Switzerland. The battle of Solferino was fought on June 24 of 1857. Like Bannockburn this was the Feast of St. John the Baptist. The story goes that a young man by the name of Henri Jean Dunant came to survey the damage. He later produced a book on the battlefield and presented it to wealthy and prominent citizens to create an international organization of relief workers. Switzerland at this time was a Confederation of 22 cantons and 3000 communes. Its neutrality was reiterated and protected by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 and confirmed by the Treaty of Vienna in 1815. Five of the prominent men met and agreed to call for a larger meeting. Prince Heinrich XIII of Reuss represented the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and became Vice President. Impressed by the St. John connection, delegates came from around the world. The HQ was at Basle. Rooms were taken in a chapel owned by the Teutonic knights.

The Country the Templars Created

Modern Switzerland has been built on banking, bank secrecy, precision engineering and pharmaceuticals. Finance is the central pillar of the Swiss economy. While bank secrecy is on the defense from the prying IRS, over five trillion dollars of “cross-border” wealth is known to be managed in Switzerland. Like the Templar bank of centuries before, the banks of Switzerland cater to national rulers, who often treat their nation’s riches as their own. The Swiss banks in turn have been accused of treating the money deposited as belonging to them. When President Mobutu of Zaire died in exile in 1997, Swiss newspapers reported he had $5 billion deposited in their banks. Swiss banks returned $8 million.

Templar scientific studies, once dubbed alchemy, are mirrored in the dominance of Swiss chemical and pharmaceutical companies. BASF, Zeochem, Novartis, and Hoffman-L Roche are Swiss companies with an international customer base.

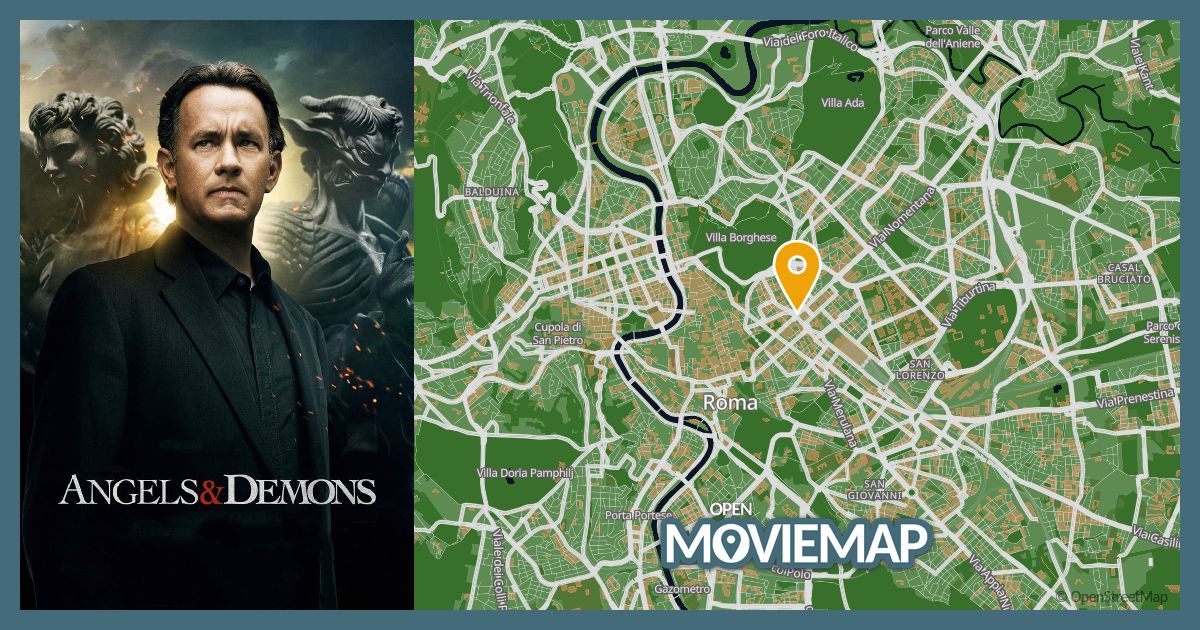

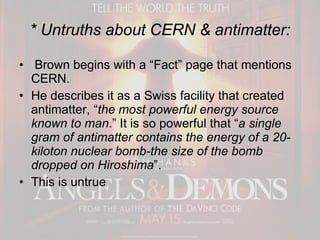

Finally, the Templars and their sister order of St. Bernard the Cistercians, were known for their engineering abilities. Today the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator sits inside the Swiss border with France. This is CERN. Most Americans heard of it only through Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons when his character Robert Langdon discovers CERN technology is going to be used to destroy the Vatican. (Other conspiracy theorists worry CERN could destroy the planet.) It should be noted it was a CERN scientist, not Al Gore, who invented the World Wide Web in 1989.

The Templar order that the French King and the Pope forced into hiding, remains alive, and hiding in plain sight, in Switzerland, the center of Europe.

https://steemit.com/history/@conspiracyhq/william-tell-and-the-templar-nation |

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 3 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

The historicity of William Tell has been subject to debate. François Guillimann, a statesman of Fribourg and later historian and advisor of the Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II, wrote to Melchior Goldast in 1607: "I followed popular belief by reporting certain details in my Swiss antiquities [published in 1598], but when I examine them closely the whole story seems to me to be pure fable."

In 1760, Simeon Uriel Freudenberger from Luzern anonymously published a tract arguing that the legend of Tell in all likelihood was based on the Danish saga of Palnatoki. A French translation of his book by Gottlieb Emanuel von Haller (Guillaume Tell, Fable danoise), published under Haller's name to protect Freudenberger, was burnt in Altdorf.[29]

The skeptical view of Tell's existence remained very unpopular, especially after the adoption of Tell as depicted in Schiller's 1804 play as national hero in the nascent Swiss patriotism of the Restoration and Regeneration period of the Swiss Confederation. In the 1840s, Joseph Eutych Kopp (1793–1866) published skeptical reviews of the folkloristic aspects of the foundational legends of the Old Confederacy, causing "polemical debates" both within and outside of academia.[30] De Capitani (2013) cites the controversy surrounding Kopp in the 1840s as the turning point after which doubts in Tell's historicity "could no longer be ignored".[31]

From the second half of the 19th century, it has been largely undisputed among historians that there is no contemporary (14th-century) evidence for Tell as a historical individual, let alone for the apple-shot story. Debate in the late 19th to 20th centuries mostly surrounded the extent of the "historical nucleus" in the chronistic traditions surrounding the early Confederacy.

The desire to defend the historicity of the Befreiungstradition ("liberation tradition") of Swiss history had a political component, as since the 17th century its celebration had become mostly confined to the Catholic cantons, so that the declaration of parts of the tradition as ahistorical was seen as an attack by the urban Protestant cantons on the rural Catholic cantons. The decision, taken in 1891, to make 1 August the Swiss National Day is to be seen in this context, an ostentative move away from the traditional Befreiungstradition and the celebration of the deed of Tell to the purely documentary evidence of the Federal Charter of 1291. In this context, Wilhelm Oechsli was commissioned by the federal government with publishing a "scientific account" of the foundational period of the Confederacy in order to defend the choice of 1291 over 1307 (the traditional date of Tell's deed and the Rütlischwur) as the foundational date of the Swiss state.[32] The canton of Uri, in defiant reaction to this decision taken at the federal level, erected the Tell Monument in Altdorf in 1895, with the date 1307 inscribed prominently on the base of the statue.

Later proposals for the identification of Tell as a historical individual, such as a 1986 publication deriving the name Tell from the placename Tellikon (modern Dällikon in the Canton of Zürich), are outside of the historiographical mainstream.[33]

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 4 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 5 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

De los Andes a los Alpes en un solo paso

Colonia Suiza fue el primer asentamiento europeo en la región. Declarado patrimonio histórico, mantiene intactas las características originales de la época de su fundación (fines del siglo XIX). Se encuentra a tan sólo 25 kilómetros de Bariloche.

Se puede degustar el tradicional curanto, una comida originariamente araucana que fue introducida desde Chile por Emilio Goye, uno de los primeros pobladores de la colonia. Su preparación es toda una ceremonia, que se puede presenciar los domingos y comienza antes del mediodía.

Además, hay varias casas de té y restaurantes, negocios de artesanías y una importante feria artesanal que se convirtió en un paseo imprescindible para todo el que visite el lugar.

En Colonia Suiza también se pueden observar las plantaciones de fruta fina que después se utiliza para elaborar exquisitos dulces, conservas, postres e insumos para repostería. Se realizan degustaciones de los productos y se pueden comprar en varios sitios de la Colonia.

https://barilocheturismo.gob.ar/es/colonia-suiza |

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 6 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 7 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 8 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 9 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 10 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 11 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

Bern Museums: Einstein’s House

By Emma Marshall

There are several Bern museums that you can visit in the Swiss capital.

However, if you’re in this lovely city, a World Heritage Site, and the place where Albert Einstein developed his theory of relativity, you really must put a visit to the house where he lived on your sightseeing list.

Read on for more information on visiting this Bern museum and for my thoughts on what I learnt here.

This post contains affiliate links

Bern Museums: where is the Einstein house?

The Albert Einstein house is situated in Bern old town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It’s on Kramgasse (specifically No.49). This is the main street that runs the length of the old town and which means “Grocer’s Alley”. It’s a lovely medieval street and you’re bound to visit it on a trip to Bern.

Kramgasse street There are long covered alleyways here, with small boutique shops under the arches. There’s also a smattering of cosy cafes and bars in basements, which would be perfect in the cold winter months.

The street is also is interspersed with a number of ornate, colourful, and quite unique fountains. At one end, you can also find the 13th century clock tower (Zytlogge). This is beautiful and lovely when lit up at night.

Bern clock tower in the old town  The Bern clock tower at night This is another must-see sight in Bern. So much so that you can book tours to learn more about the clock and to go inside. Click here to learn more.

You can also book walking tours of the old town: click here.

Bern Museums: why visit the Einstein House?

Einstein is not the only famous or noteworthy person connected to this Swiss canton. Others include the Nobel Prize winner, Emil Kocher, and the Bond actress Ursula Andress.

However, he is the one that the city – understandably – is most proud of.

This is because it was in Bern that he first sowed the seeds for his famed work on the General Theory of Relativity. He himself said: “Those were good times, the years in Bern”, of his seven years in the Swiss capital.

So when deciding which Bern museum to visit, you really should include one about Einstein.

You can actually learn about Einstein’s time in the Swiss capital in two Bern museums. Aswell as Einstein’s house, there is the Bern Historical Museum.

According to the website, this has “some 550 original objects and replicas, 70 films and numerous animations outline the biography of the genius and his ground-breaking discoveries”.

Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here As we had limited time in the capital, we chose to focus on Einstein’s house and the museum that is housed there. However, if I returned, I would definitely visit the Bern Historical Museum as well.

Bern Museums: The Einstein house

Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)The Einstein House is the flat that Einstein occupied from 1903 to 1905 with his wife, Mileva Maric. Mileva was herself a promising physicist from Serbia.

The house is very small, so this is a Bern museum that can get easily crowded. I’d therefore recommend visiting early to ensure you get in.

The museum has a large selection of exhibits and photographs from the couple’s life together. On the first floor, these are displayed around the flat as it presumably was laid out at the time.

Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)A small table is in the middle of the room where the family would have eaten. Chairs are where they would have relaxed, and there is a writing bureau, and cabinet housing a tea service and coffee pots.

All are overlooked by fascinating old photos of the family that hang on the walls and that depict different chapters of their life.

Upstairs, there is an informative short film. This draws on archive footage, that charts Einstein’s life from his early days through to later years. Make sure you watch this – it is essential viewing. It really brings alive the life of the man.

Bern Museums: What’s interesting about this particular museum?

Einstein’s work

The museum is interesting on several levels. Firstly, for what you learn about Einstein’s great work and the foundations for this.

His first job was with the Swiss Patent Office which he held down whilst simultaneously writing his scientific papers. These included the forerunner to his work on the Theory of Relativity and another which won him a Nobel Prize in 1921.

He then moved into academia at the University of Bern before moving to Zurich. There were other stints in Prague and Berlin, before his later life spent in the United States.

Einstein’s personal life

This Bern Museum is also interesting for the insight it gives you into the personal life of Einstein. I found this utterly engrossing.

We all grow up knowing that Einstein is significant for his scientific work and discoveries. What we know less about (or certainly I knew less about) are the life stories running alongside in the background.

Much of this revolves around Einstein’s personal relationships and the consequences of these. Some of these are very sad. For example, he had a child born out of wedlock and a second relationship while still married.

He married Mileva Malic in 1903, but had in fact had a daughter, Leiserl, with Mileva the previous year. Leiserl was born in Mileva’s home country of Serbia. She was left to grow up with her grandparents, presumably because she was illegitimate.

According to the museum exhibition, Einstein himself never met his daughter. Her sheer existence was kept secret during his lifetime. To this day what happened to Liserl is a mystery.

Mileva and Einstein went on to raise two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard. They remained married until 1919 when Einstein remarried – to his cousin, Elsa Lowenthal. It seems he had forged a relationship with her some time before his marriage to Mileva formally dissolved.

Einstein’s move to the USA

The museum also tells the story of Einstein’s move to the USA. This coincided with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany and the difficulties that this presented to him.

Most notably these included the impossibility of working there as a German Jew. Scores of Jewish academics were being forced out of work, Nazi book burnings were taking place, and Einstein was vocalising his views on the treatment of Jews within Germany.

He therefore took up a role at Princeton University in the USA, and it is there that he remained until his death in 1955.

Einstein’s wife

Although this Bern museum is only small, you can learn a great deal in a short time, some of it possibly unexpected. And whilst I went to learn more about Einstein, I came away with a long lasting impression of his wife.

I developed an equal admiration for his wife, partly because of all that she seemed to go through during her time with Einstein. This included a child that was given up, a broken marriage and the forfeiture of her own academic ambitions.

It also seems that Mileva may have been important not only for her support of Einstein’s ambitions, but more directly for her role in actually furthering these.

Some think that letters between the couple show her contribution. It is thought that she contributed in the early days to Einstein’s ground-breaking work and that her own expertise in physics is reflected in some of his work.

So, in addition to learning a lot about Einstein himself, I learnt a lot about the wife of one of the world’s greatest scientists. I came away with a real sense that the adage about there being a great woman behind every man was really true of Mileva.

Bern Museums: visiting the Einstein house

Opening times

You can visit the house between 1st February and 21st December. Exceptions include Easter, Pentecost and Switzerland’s National Day (1st August).

Opening times are 9am to 5pm. Entry costs CHF 6 for adults (reduced rates apply for students, pensioners and those between 8 and 15 years: CHF 4.50, 4.50 and 3, respectively).

Getting to Bern

Bern has an airport and you can catch flights here from various cities in Germany, as well as from London (City airport), Vienna and Palma.

However, it is smaller than both the Swiss airports in Geneva and Zurich that have more regular flights. Bern is just over an hour via train from Zurich airport and around two hours to Geneva airport. You might therefore find it more convenient to catch a flight to one of these airports.

You can also visit Bern from other Swiss cities. Lausanne and Lucerne are both around an hour away by train. Interlaken is around 45 mnutes and Nuechatel just under 50 minutes.

If public transport is not your thing, you can also book day trips to Bern. Click here for ideas.

Other Bern Museums to visit

Aside from the history museums, there are other Bern museums to visit.

These include a fine arts museum, a communications museum and a Swiss alpine museum – see http://www.museen-bern.ch/en/for further information.

If you enjoy short trips to Europe, you may also find some of my other posts of interest:

https://www.travelonatimebudget.co.uk/switzerland/bern-museums-einsteins-house/ |

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 12 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

Different cyclotron size: a) Lawrence ́s first one, b) Venezuela First one (courtesy of Dorly Coehlo), c) Fermi National Laboratory at CERN. And size matters, and Cyclotrons win as best hospital candidates due to Reactors are bigger, harder and difficult to be set in a hospital installation. Can you imagine a nuclear reactor inside a health installation? Radiation Protection Program will consume all the budget available. Size, controlled reactions, electrical control, made cyclotrons easy to install, and baby cyclotrons come selfshielded so hospital don ́t need to spend money in a extremely large bunker. Now on, we are going to talk about our first experience with the set up of a baby cyclotron for medical uses inside the first PET installation in Latin America. “Baby” means its acceleration “D” diameters are suitable to be set inside a standard hospital room dimensions, with all its needs to be safetly shielded for production transmision and synthetized for human uses for imaging in Nuclear Medicine PET routine. When we ask why Cyclotrons are better than reactors for radioisotopes production to be used in Medicine, we also have to have in mind that they has: 1. Less radioactive waste 2. Less harmful debris

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Different-cyclotron-size-a-Lawrence-s-first-one-b-Venezuela-First-one-courtesy-of_fig3_221906035

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 13 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 14 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 15 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

William Tell and The Templar Nation

The history of Switzerland is, at best, elusive. It is that way seemingly on purpose, with its origins murky. Its…

You must be logged in to view this content.

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 16 di 16 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

Primo

Primo

Precedente

2 a 16 de 16

Successivo

Precedente

2 a 16 de 16

Successivo

Ultimo

Ultimo

|

![La Novicia Rebelde (1 Disco) [Blu-ray] : Julie Andrews, Christopher Plummer, Eleanor Parker, Robert Wise, Robert Wise;Saul Chaplin: Amazon.com.mx: Películas y Series de TV](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/61PwK5UT82L._AC_UF894,1000_QL80_.jpg)

Kramgasse street

Kramgasse street Bern clock tower in the old town

Bern clock tower in the old town The Bern clock tower at night

The Bern clock tower at night Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here

Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)

Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)

Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)