|

|

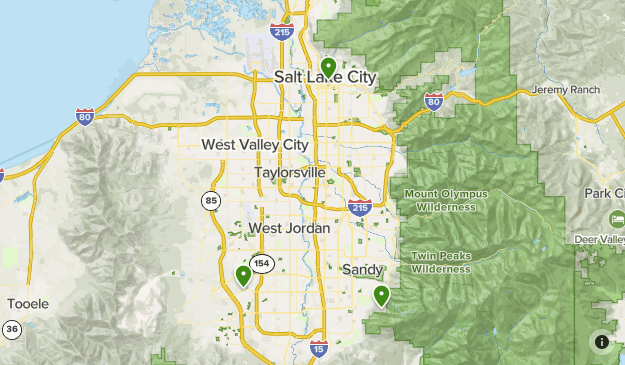

salt lake city=alchemy (salt)=dollar=$= LOT S WIFE (SODOMA AND GOMORRA)

|

|

|

|

|

| Enviado: 03/06/2024 10:05 |

|

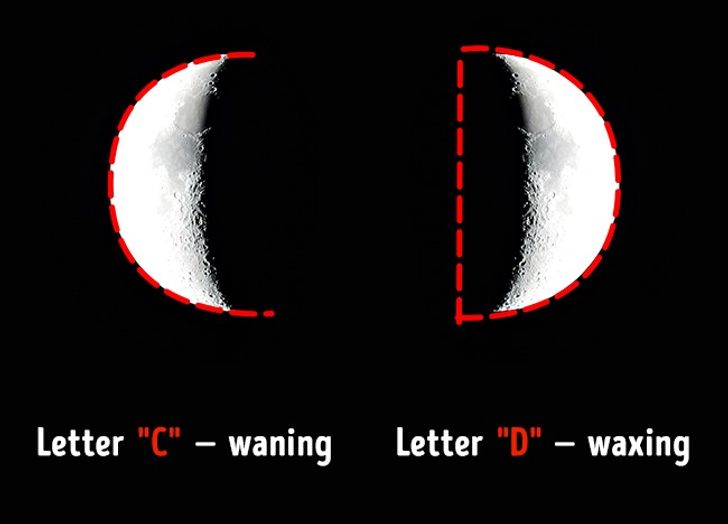

DREAMS=D-REAMS=LETTER D

|

|

|

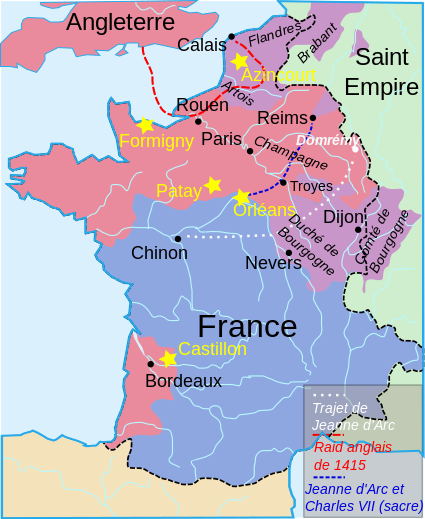

CHAMPAGNE=TROYES (VERDADERA TROYA)

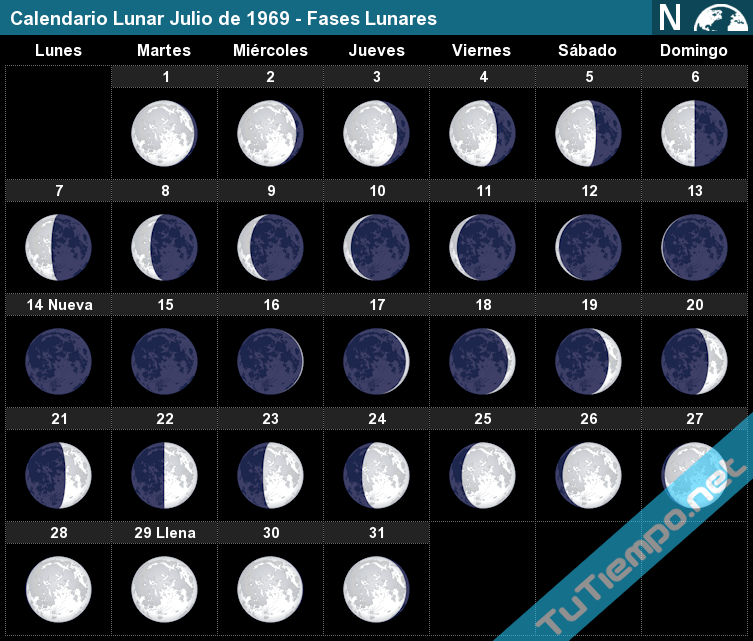

Día de Nuestra Señora de la Magdalena, 22 de julio

|

|

|

|

|

|

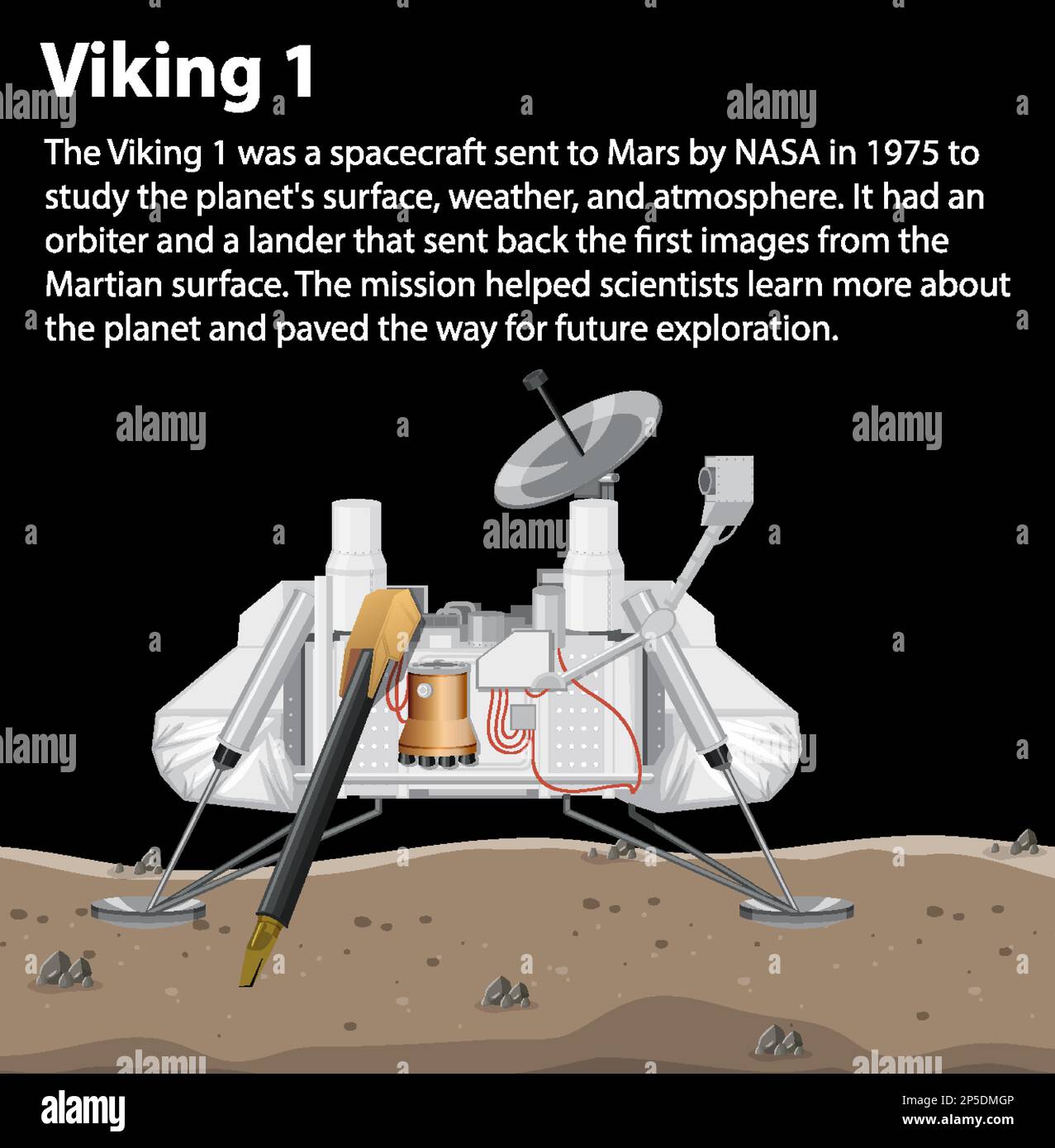

Viking 1

Viking orbiter/lander

|

| |

| Mission type |

Orbiter and lander |

| Operator |

NASA |

| COSPAR ID |

Orbiter: 1975-075A

Lander: 1975-075C |

| SATCAT no. |

Orbiter: 8108

Lander: 9024 |

| Website |

Viking Project Information |

| Mission duration |

Orbiter: 1,846 days (1797 sols)

Lander: 2,306 days (2,245 sols)

Launch to last contact: 2,642 days |

| |

| Manufacturer |

Orbiter: NASA JPL

Lander: Martin Marietta |

| Launch mass |

3,530 kg[a] |

| Dry mass |

Orbiter: 883 kg (1,947 lb)

Lander: 572 kg (1,261 lb) |

| Power |

Orbiter: 620 W

Lander: 70 W |

| |

| Launch date |

21:22, August 20, 1975 (UTC)[2][3] |

| Rocket |

Titan IIIE/Centaur |

| Launch site |

LC-41, Cape Canaveral |

| |

| Last contact |

November 11, 1982[4] |

| |

| Reference system |

Areocentric |

| |

| Spacecraft component |

Viking 1 Orbiter |

| Orbital insertion |

June 19, 1976[2][5] |

| Periareion altitude |

320 km (200 mi) |

| Apoareion altitude |

56,000 km (35,000 mi) |

| Inclination |

39.3° |

| Spacecraft component |

Viking 1 Lander |

| Landing date |

July 20, 1976[2]

11:53:06 UTC (MSD 36455 18:40 AMT) |

| Landing site |

22.27°N 312.05°E[2] 22.27°N 312.05°E[2] |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is the proof test article of the Viking Mars Lander. For exploration of Mars, Viking represented the culmination of a series of exploratory missions that had begun in 1964 with Mariner 4 and continued with Mariner 6 and Mariner 7 flybys in 1969 and a Mariner 9 orbital mission in 1971 and 1972. The Viking mission used two identical spacecraft, each consisting of a lander and an orbiter. Launched on August 20, 1975 from the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, Viking 1 spent nearly a year cruising to Mars, placed an orbiter in operation around the planet, and landed on July, 20 1976 on the Chryse Planitia (Golden Plains). Viking 2 was launched on September 9, 1975 and landed on September 3, 1976. The Viking project's primary mission ended on November 15, 1976, 11 days before Mars's superior conjunction (its passage behind the sun), although the Viking spacecraft continued to operate for six years after first reaching Mars. The last transmission from the planet reached Earth on November 11, 1982.

While Viking 1 and 2 were on Mars, this third vehicle was used on Earth to simulate their behavior and to test their responses to radio commands. Earlier, it had been used to demonstrate that the landers could survive the stresses they would encounter during the mission.

NASA transferred this artifact to the Museum in 1979.

|

|

|

|

|

After gentle touchdown on Mars, Viking sends back 'Incredible' photos

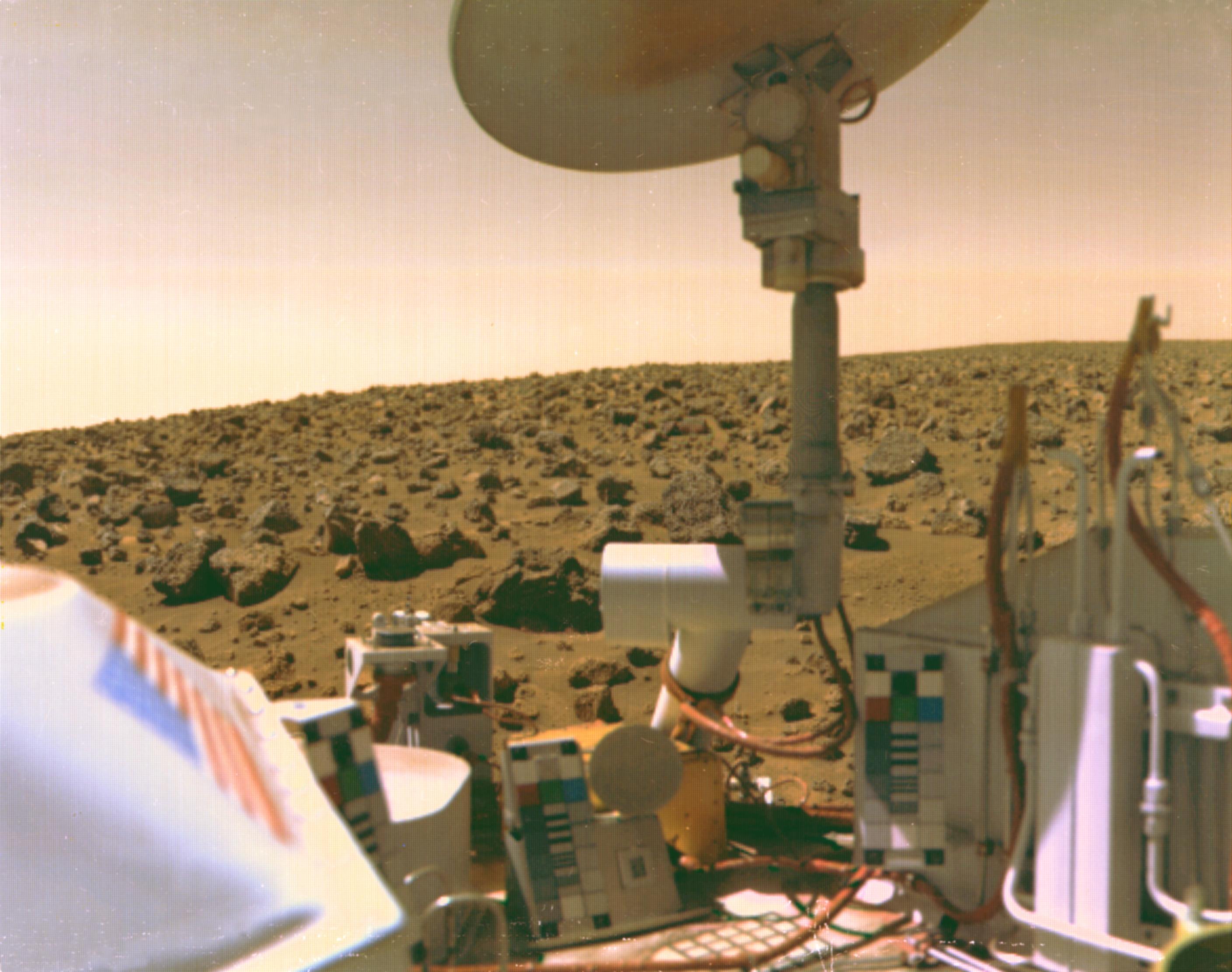

On July 20, 1976, at 8:12 a.m. EDT, NASA received the signal that the Viking Lander 1 successfully reached the Martian surface. This major milestone represented the first time the United States successfully landed a vehicle on the surface of Mars, collecting an overwhelming amount of data that would soon be used in future NASA missions. Upon touchdown, Viking 1 took its first picture of the dusty and rocky surface and relayed the historic image back to Earthlings eagerly awaiting its arrival. Viking 1, and later Viking Orbiter 2, collected an abundance of high-resolution imagery and scientific data, blazing a trail that will one day take humans to Mars. File Photo courtesy NASA | License Photo

PASADENA, Calif. (UPI) - America's Viking 1 space robot landed gently on Mars today and radioed back the first pictures taken from the planet's surface -- "incredible" photos showing a sandy, rocky Martian desert with a gently rolling horizon.

The three-legged spacecraft rode a fusion of rocket exhaust to a gentle touchdown in a lowland considered one of the best places for its instruments to conduct the first search for life on the red planet.

The landing on the planet more than 200 million miles from earth opened a new frontier in man's exploration of the solar system. President Ford said in a telephone call to space agency officials the flight was "just wonderful and a most remarkable success."

The initial image from one of Viking's twin cameras started coming in at the control center at 8:55 a.m. EDT. The shot looked down and showed one of the Viking's footpads.

It was readily apparent that the Martian soil was littered with rocks. It appeared the soil had been blown by wind or thrust from Viking's landing rockets.

A few minutes later, after the camera raised its lens on command from a computer, a broad panoramic view of the landscape appeared line by line on control center monitors. It was late afternoon there and the setting sun appeared to brightly illuminate the distant sky.

There was no evidence of any life forms in the initial pictures. But scientists did not expect to see any.

Unlike pictures taken from the moon, the Martian surface did not appear pock marked with sharp craters. This apparently was the result of wind erosion on Mars. The planet has occasional dust storms and Viking was coated with a gray resilient paint to protect it from sand blast effects.

"This is just an incredible scene," said Dr. Thomas Much, geologist in charge of the photographic experiment. "It looks safe and very interesting."

"The resolution is just fantastic," Mutch said as he and hundreds of others at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory watched the image form on television monitors. "The detail is incredible."

Viking's descent to Mars was flawless. Engineers called out the various landing operations as they learned of them by radio reports from Mars and there was no hesitation when Viking landed.

"We have touchdown," exclaimed a Viking control spokesman at 8:12 a.m. EDT.

"Looking good," echoed engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory seconds after touchdown. "Fantastic, beautiful," said one controller.

Engineers listened anxiously as word of Viking's parachute operation came in, followed by ignition of the landing rockets. There was a loud cheer in the control center when the first report of a safe landing reached the control center at 8:12 a.m. EDT - 18.8 minutes after the radio signals were transmitted from Viking.

Twenty-five seconds after touchdown, the 10-foot wide lander started taking the first picture. It was beamed to the still-orbiting section of Viking which radioed it back to Earth a few minutes later.

Mutch said it appeared Viking's long mechanical arm would have no difficulty scooping up soil for biology and chemical analysis experiments to be turned on later.

The footpad picture showed that Viking landed with minimum impact. The photo was so sharp rivets could be soon on the top of the aluminum foot with a shadow of higher apparatus.

It was the second landing on Mars of a spacecraft from Earth. Russia accomplished the feat in 1971 but its lander failed 20 seconds later without sending back useful data.

Viking 1 began the final leg of its 11-month journey from Earth 3 hours 21 minutes before touchdown when three explosive bolts holding the lander to its orbiting mother craft were detonated. At that point, Viking was 11,400 miles high, traveling at 3,040 miles per hour on its 29th orbit of Mars.

Eight small rockets then fired for 22 minutes to begin Viking's descent into the atmosphere. Viking sliced into the upper fringes of the Martian gases and temperatures as high as 2,730 degrees Fahrenheit built up outside a saucer-like heat shield.

Viking's descent at that point was very shallow, allowing atmospheric drag to slow the craft enough so a 53-foot wide parachute could be deployed 19,000 feet high.

Acting on commands from its onboard computers, Viking then jettisoned its protective shell and a few seconds later unfolded its three landing legs.

Less than a mile above mars, and guided by four radar beams, Viking jettisoned its parachute and three powerful landing rockets fired. This slowed the spacecraft so it dropped to Mars traveling about 5 1/2 mph - an impact similar to what one would feel jumping off a table on Earth.

Mars gravity accelerated the lander to as much as 10,000 mpg as it neared the planet. When it hit the thicker parts of the "air," engineers reported the craft was feeling acceleration forces eight times the force of earth gravity.

https://www.upi.com/Archives/1976/07/20/After-gentle-touchdown-on-Mars-Viking-sends-back-Incredible-photos/8721500224068/ |

|

|

|

|

Oak Island – the Templar and Viking connection!

Since the mid-nineteenth century, Oak Island has been claimed as the site for a vast, secretly hidden store of Templar treasure. Possibly the location of priceless items they discovered under the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem.

Vast amounts of money have been spent excavating below ground to find millions of dollars worth of medieval booty. Companies have been set up with the sole task of getting to the treasure left behind by these enigmatic warrior knights. So – is the wealth of the Templars actually there?

Of course the answer is – we don’t know. But let’s try and figure out how the story has come about and why it still exercises such a tremendous hold on the popular imagination.

The Viking link to Oak Island

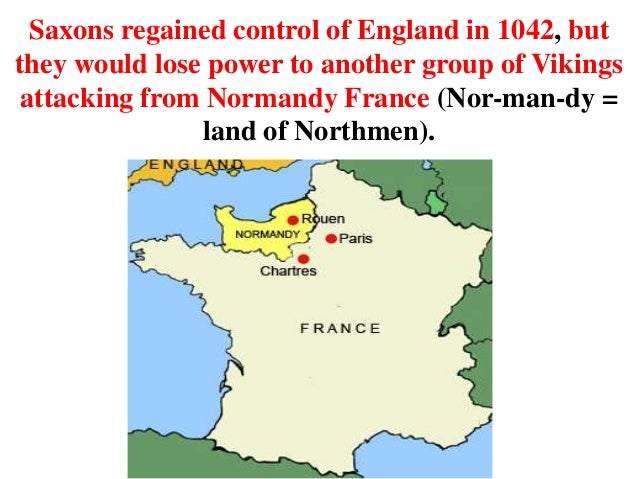

I think a good starting point are the claims made in the 20th century that the Vikings had got to the New World long before Christopher Columbus. Why is this important? Because if the Vikings could have got there – then why not the Templars?

This theory has been supported by the so-called Vinland map (dating from the 15th century), that seems to show our Viking ancestors touched down in north America. Trouble is, the map is just a little too good to be true and even though scholars from the British Museum and Yale backed it up in the 1960s, the evidence (for example dating of the ink) suggests it could be a forgery.

If it was true, the Vinland map would establish the feasibility of Europeans sailing across the Atlantic to the American coastline. It’s not beyond the realms of possibility because the Vikings did get to Iceland and Greenland. Some Templar conspiracy theorists suggest the knights or those who helped them had access to Viking navigation charts.

TEMPLAR EXCLUSIVE: Do you want to find your Templar ancestors?

The Templars and Oak Island

Moving away from the Vikings now, let’s shift our focus to the Knights Templar. In 1307, their number was up. Philip, king of France, had ordered the arrest of all the knights and they were interrogated under torture in various dungeons. But if the king had hoped to find lots of loot at the Paris Temple, their headquarters, he was to be severely disappointed. Only empty shelves greeted his soldiers.

We then get the story of Templar treasure being spirited away from Paris in wagons bound for the port of La Rochelle and from there on to Scotland (and/or maybe Portugal, see my other blog posts on that option). And then – the wealth of the Templars simply evaporates into thin air!

In his book Lost Treasure of the Knights Templar: Solving the Oak Island Mystery, Steven Sora claims that the Templars’ treasure – gold, silver, jewels and sacred relics of immense power – were firstly hidden away in the crypt at Rosslyn chapel by the Sinclair family. The Sinclairs are central to the whole Templar getaway-via-Scotland theory.

The Sinclair connection

Quick detour on the Sinclair family then. They are an ancient Scottish family that includes Henry, the first earl, who fought alongside the first Grand Master of the Templars, Hugh de Payens (or Payns) in the Holy Land in the early 12th century. So, we have an early association between this family and the order of knights.

Fast forward to the early 14th century and Sir William Sinclair (sometimes spelt St Clair or Saint-Clair) is sometimes held up to have been the last Templar Grand Master before his death in 1330. Trouble is, he also appears to have given evidence at their trials AGAINST the Templars – somewhat scuppering that theory unless he was involved in some kind of complex double bluff!

Then we have another Henry Sinclair who in the late 14th century allegedly explores the coast of north America with an Italian navigator called Antonio Zeno. This establishes the idea that the Sinclair family know all about the New World so are ready for a subsequent very important voyage.

According to Steven Sora, the Sinclairs leave the Templar treasure under Rosslyn until the 16th century. But then along comes the Protestant Reformation. The Sinclairs are devout Catholics. Fearing that that the Templar treasure might be seized, they set sail with it and land on…Oak Island!

Daniel McGinnis on Oak Island

Now, nothing more gets said about this – obviously, being a secret mission – until the 19th century. Then stories circulate in newspapers of discoveries made on the island by a man called Daniel McGinnis in the 1790s. I’ve read different versions of the McGinnis story. In one account, he found a curious depression in the ground while setting up his farm. Or, he saw unusual lights on the island one evening and sailed across, discovering the pit when he got there.

The story of McGinnis and his excavations only emerges fifty years later in a paper called the Liverpool Transcript. By the mid-nineteenth century, tales of pirates and their hidden treasure had become the stuff of boys’ magazines. In 1881, the author Robert Louis Stevenson would publish Treasure Island in a boys’ magazine called Young Folks. The Oak Island booty came to be associated with both the Templars and notorious pirates like Captain Kidd and Blackbeard.

This was also an era of gold rushes – speculators dashing to reputed finds of the precious metal. So, maybe not entirely surprising that Oak Island was soon swarming with diggers. The main attention was the Oak Island Money Pit. This was a curious shaft with what appeared to be booby traps set at different levels.

Most intriguing was the discovery of a stone slab that allegedly has carved on it the message: Forty feet below, two million pounds lay buried. That line is best said if you impersonate Nicholas Cage in the movie National Treasure. More seriously, at least six people have died investigating the very deep money pit due to flooding and in one case, a boiler exploding.

The Franklin Roosevelt connection

One well known Oak Island devotee was the US president Franklin Roosevelt (pictured above). The Democrat occupant of the White House through the 1930s was a Freemason and from his youth until his death in 1945, retained an abiding interest in the site. One feature that apparently gripped him was the rumour that the jewels of the last queen of France, Marie Antoinette, had been squirrelled away on the island.

Which brings us to the 21st century! Such is the level of interest in Oak Island that the History channel has just commissioned a whopping 30 hours for season six of its series The Curse of Oak Island. This runaway success of a documentary series features two Michigan brothers Rick and Marty Lagina who have bought much of Oak Island to pursue the treasure hunt. They are accompanied by local expert, Dan Blankenship.

Rick is a retired US postal worker who passionately believes something lurks under the surface. His brother Marty is the sceptical foil raising doubts every so often about their enterprise. However, as the digs proceed, Marty is seen to convert by degrees to the cause.

The programme has attracted an impressive four million views. And it’s spawned two spin-offs: The Curse of Civil War Gold and Yamashita’s Gold. The first spin-off speaks for itself. The second is the alleged burial of treasure by Japanese soldiers in the closing days of World War II in the Philippine jungle.

In case you missed my recent outing on the History channel – I appeared in episode four of the Templar documentary series Buried earlier this year. Together with presenters Mikey Kay and Garth Baldwin, we looked for Templar treasure in the ancient citadel of Tomar in Portugal.

https://thetemplarknight.com/2018/10/14/oak-island-templars-vikings/ |

|

|

|

|

Who Were the Knights Templar ?

While most people have heard of the Knights Templar and now that they have something to do with the Crusades, few people know much about their history or their Viking connection.

This is a brief history of the Knights Templar that highlights some of the practices that they seem to have borrowed from Viking warrior traditions.

Origins of the Knights Templar

The First Crusade, between 1096 and 1099, was authorized by the Pope to try and take the Holy Land and bring it under Christian (or more specifically papal) control.

Many European Christian knights were recruited to join the fight, and in return for their service, they would be forgiven for all the sins that they confessed.

So, the Crusades also gave the Church a chance to bring knights who had begun to exploit their wealth and position under control.

The Crusaders eventually captured Jerusalem in June 1099. But the almost 10,000 knights (not to mention foot soldiers and non-combatants) wanted to come home.

Only around 300 knights were left behind to defend what was conquered and guarantee Christian pilgrims access to the Holy Land.

For that purpose, some of the devout knights who stayed behind would officially form the Oder of the Poor Knights of the Temple of Jerusalem in 1118/1119, better known as the Knights Templar.

They were officially recognized by King Baldwin II of Jerusalem in 1120 and were assigned tax revenue to them to keep them clothed and fed, though most were wealthy in their own right.

They were also exempt from paying tax or tithes to the church.

Now organized, the Knights Templar became a powerful, wealthy, and influential organization in both the Holy Land and Europe.

They created castles and strongholds in the Holy Land that were used during subsequent crusades.

Their main headquarters were located on the Temple Mount in a wing of the Al-Aqsa Mosque, rumored to be built on top of the Temple of King Solomon.

They were so wealthy that they are sometimes described as the first bankers.

What they actually did was hold the wealth of knights who went off to the Holy Land in their repositories.

They would also lend their wealth to important projects, such as the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

Code of the Brotherhood

Traditional clothing of the Knights Templar Traditional clothing of the Knights Templar

More than just an arrangement of convenience, this was a religious calling for the knights.

They were led by a Grand Master, who was like a dictator and held the position for life.

The first Grand Master of the Knights, Hugh de Payens, established a 72-point code of conduct for members known as Primitive or Latin Rule.

These were specifically designed to increase the piety and zeal of the brothers.

The strict rules dictated what Templars could wear, the types of horses they could ride, the length of their hair and style of their beards, and what meat they could eat.

They wore a white surcoat and red cross representing Christ’s sacrifice and their own willingness to sacrifice themselves.

The rules also forbade contact with women, a rule that was probably largely ignored.

The knights were also required to take their meals in silence and there were scheduled prayers at canonical hours.

They were never allowed to retreat unless they were outnumbered by at least three to one, and they were not allowed to surrender unless their flag had fallen, in which case they were required to regroup.

This commitment to discipline, along with excellent training and heavy armament, made the Templars one of the most feared fighting forces for 200 years.

End of the Knights Templar

Burning of the Knights Templar Burning of the Knights Templar

While there were several waves of crusades, the Holy Land was eventually lost to Muslim forces at the end of the 13th century.

The knights who were involved, including the Templars, were held responsible, especially after Acre was taken in 1291.

The decision to disband the Templars was probably because the king of France owed them quite a lot of money.

He ordered the mass arrest of French Templars and their property confiscated.

The name of the Templars was dragged through the mud and they were accused of heresy, such as spitting on the cross, illicit sexual acts, and sacrilegious and perverted ceremonies and beliefs, which included kissing one another.

Under torture, the Templars confessed to the charges. While they were absolved of heresy by the Pope in 1308, the order was disbanded, and their wealth was already seized by powerful men.

Some individual Templars would continue to be persecuted.

The last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, was burned at the stake for heresy.

In Portugal, however, the king refused to prosecute Templars and they were able to thrive there and reform under the name Order of Christ.

This haven is often a gateway to conspiracy theories about the Templars never truly dissolving.

Most famously, Freemasons claim to have an ancient connection with the Templars and use many of the same symbols and ranks.

They once claimed to be directly descended from 14th-century Templars who took refuge in Scotland and helped Robert the Bruce win his battle at Bannockburn against the English for Scottish independence. This is now agreed to be a myth.

What’s the Viking Connection ?

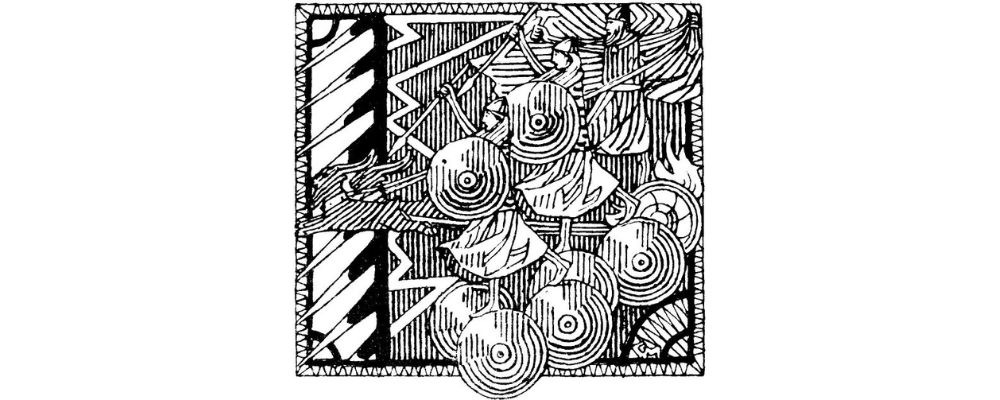

Image of the Jomsvikings, by Gerhard Munthe, 1899. Image of the Jomsvikings, by Gerhard Munthe, 1899.

The idea of the call of a warrior also being a religious calling would have been familiar in the Viking world.

Even early in the Viking age, berserker warriors were part of a religious order that followed specific rules and engaged in rituals to commune with the spirits of ferocious animals before battle in order to fight better.

But even more relevant were the Jomsvikings, a legendary group of Danish Vikings who probably lived in what is now Poland and formed an elite order in the 10th and 11th centuries.

They also lived by a strict code.

They only accepted men between the ages of 18 and 50, and they had to be sponsored by an existing member.

They were not allowed to leave their stronghold for more than three days without permission and women were never allowed in the stronghold.

The Jomsvikings were not allowed to show fear in the face of the enemy and could never flee from a fight and were only allowed to retreat when severely outnumbered.

They could not speak poorly of one another and were honor-bound to defend their brothers. All spoils were shared equally among the brothers.

It might not be a coincidence that Norwegian Christian Vikings traveled around the Holy Land between 1110 and 1112, and met with King Baldwin I, one of the advocates of the Templars.

They may have brought Vikings and stories, embodied by the Jomsvikings, with them to the Holy Land.

https://blog.vkngjewelry.com/en/who-were-the-knights-templar/ |

|

|

|

|

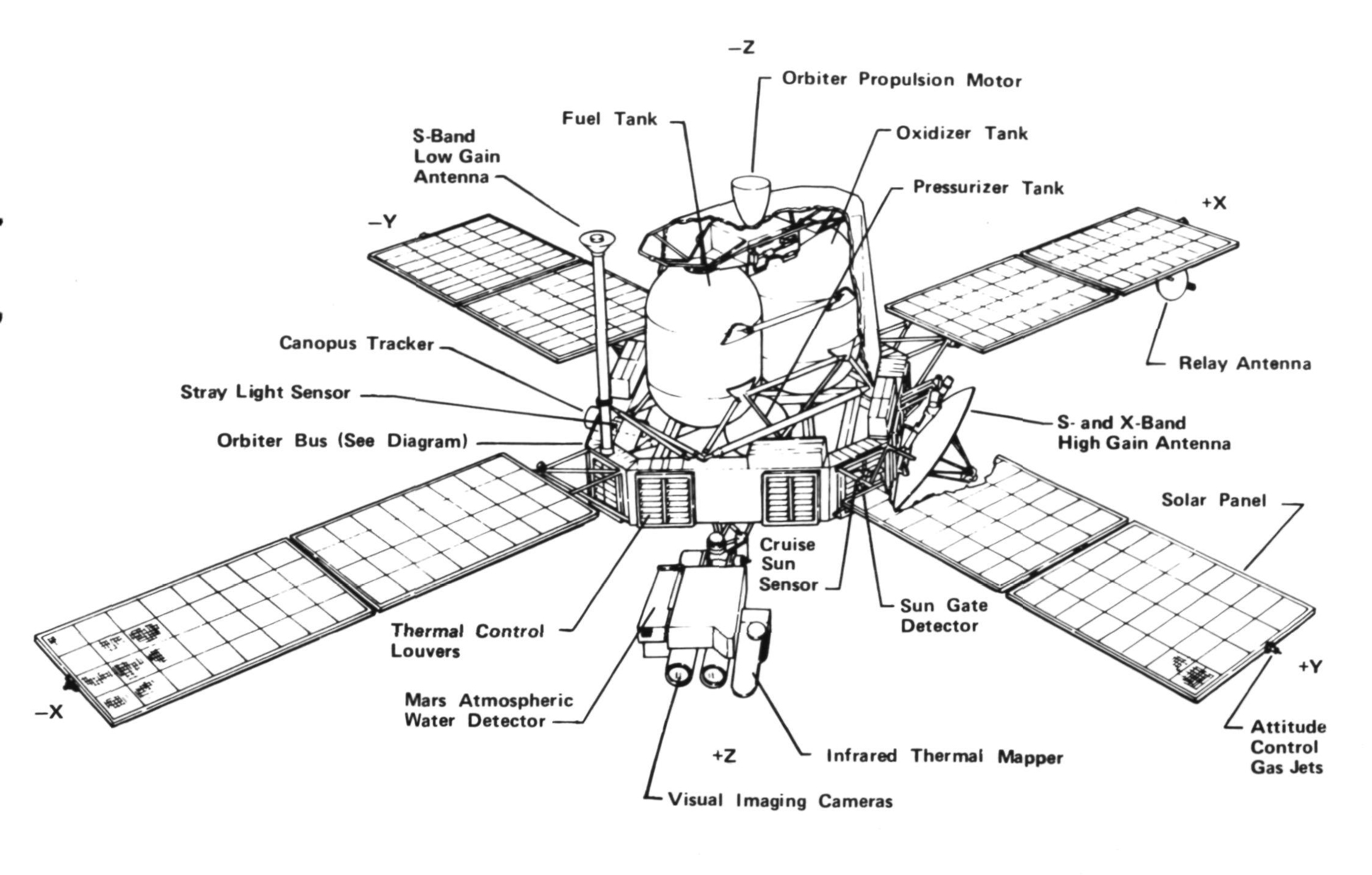

Both NASA Viking missions used a combination of orbiter and lander to explore Mars in unprecedented detail.

- Viking 2 entered orbit around Mars on Aug. 7, 1976.

- The lander touched down safely on Sept. 3, 1976, about 4,000 miles (6,460 kilometers) from the Viking 1.

- In total, the two Viking orbiters returned 52,663 images of Mars and mapped about 97 percent of the surface at a resolution of 984 feet (300 meters) resolution. The landers returned 4,500 photos of the two landing sites.

| Nation |

United States of America (USA) |

| Objective(s) |

Mars Landing and Orbit |

| Spacecraft |

Viking-A |

| Spacecraft Mass |

7,776 pounds (3,527 kilograms) |

| Spacecraft Power |

Lander each carried two SNAP-19 Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs); Orbiters were solar-powered |

| Mission Design and Management |

NASA Langley Research Center (LaRC) / NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) |

| Launch Vehicle |

Titan IIIE-Centaur (TC-3 / Titan no. E-3 / Centaur no. D-1T) |

| Launch Date and Time |

Sept. 9, 1975 / 18:39:00 UT |

| Launch Site |

Cape Canaveral, Fla. / Launch Complex 41 |

| Scientific Instruments |

Orbiter

1. Imaging System (2 Vidicon Cameras) (VIS)

2. infrared Spectrometer for Water Vapor Mapping (MAWD)

3. Infrared Radiometer for Thermal Mapping (IRTM)

Lander

1. Imaging System (2 facsimile cameras)

2. Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS)

3. Seismometer

4. X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometer

5. Biological Laboratory

6. Weather Instrument Package (Temperature, Pressure, Wind Velocity)

7. Remote Sampler Arm

Aeroshell

1. Retarding Potential Analyzer

2. Upper-Atmosphere Mass Spectrometer

3. Pressure, Temperature, and Density Sensors |

Aug. 7, 1976: Viking 2 entered orbit around Mars

Sept. 3, 1976: Lander touches down safely on the surface of Mars

July 24, 1978: End of orbiter operations

April 12, 1980: End of lander mission

The Viking-A spacecraft was scheduled to be launched first but ended up being launched second due to a problem with its batteries. It was renamed Viking 2.

After a successful launch and a course correction Sept. 19, 1975, Viking 2 entered orbit around Mars nearly a year after launch Aug. 7, 1976. Initial orbital parameters were 933 × 22,200 miles (1,502 × 35,728 kilometers) inclined at 55.6 degrees.

As with Viking 1, photographs of the original landing site indicated rough terrain, prompting mission planners to select a different site at Utopia Planitia near the edge of the polar ice cap where water was located and where there was a better chance of finding signs of life.

The lander separated from the orbiter without incident at 20:19 UT Sept. 3, 1976, and after atmospheric entry, landed safely at 22:37:50 UT, about 4,000 miles (6,460 kilometers) from the Viking 1 landing site. Touchdown coordinates were 47.968 degrees north latitude and 225.71 degrees west longitude.

Photographs of the area showed a rockier, flatter site than that of Viking 1. The lander was in fact tilted 8.5 degrees to the west. Panoramic views of the landscape showed a terrain different from that of Viking 1, with much less definition and very little in the way of horizon features. Because of the lack of general topographical references on the ground, imagery from the orbiters was unable to precisely locate the lander.

The biology experiments with scooped up soil collected on three occasions (beginning Sept. 12, 1976) produced similar results to its twin: inconclusive on whether life exists or ever has existed on the surface of Mars. Scientists believed that Martian soil contained reactants created by the ultraviolet bombardment of the soil that could produce characteristics of living organisms in Earth soil.

On Nov. 16, 1976, NASA announced that both Viking 1 and Viking 2 missions had successfully accomplished their mission goals and announced an extended mission that continued until May 1978 followed by a "Continuation Mission" until July 1979.

The orbiter continued its successful imaging mission, coming within 17 miles (28 kilometers) of the Martian Moon Deimos in May 1977.

A series of leaks prompted termination of the Viking 2 orbiter operations July 24, 1978, while the Viking 2 lander continued to transmit data until April 12, 1980.

In July 2001, the Viking 2 lander was renamed the Gerald Soffen Memorial Station after Gerald Soffen (1926-2000), the NASA Project Scientist for Viking who had died recently.

In total, the two Viking orbiters returned 52,663 images of Mars and mapped about 97% of the surface at a resolution of about 980 feet (300 meters) resolution.

The Viking landers returned 4,500 photos of the two landing sites.

https://science.nasa.gov/mission/viking-2/ |

|

|

|

|

Hoja informativa del proyecto Viking

Cortesía de la NASA

Viking fue la culminación de una serie de misiones para explorar el planeta Marte ; comenzaron en 1964 con el Mariner 4, y continuaron con los sobrevuelos del Mariner 6 y 7 en 1969, y la misión orbital del Mariner 9 en 1971 y 1972.

La Viking fue diseñada para orbitar Marte y aterrizar y operar en la superficie del planeta. Se construyeron dos naves espaciales idénticas, cada una compuesta por un módulo de aterrizaje y un orbitador.

El Centro de Investigación Langley de la NASA en Hampton, Virginia, fue el responsable de la gestión del proyecto Viking desde su inicio en 1968 hasta el 1 de abril de 1978, cuando el Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro asumió la tarea. Martin Marietta Aerospace en Denver, Colorado, desarrolló los módulos de aterrizaje. El Centro de Investigación Lewis de la NASA en Cleveland, Ohio, fue el responsable de los vehículos de lanzamiento Titán-Centauro. La tarea inicial del JPL fue el desarrollo de los orbitadores, el seguimiento y la adquisición de datos, y el Centro de Control de Misión y Computación.

La NASA lanzó ambas naves espaciales desde Cabo Cañaveral, Florida: la Viking 1 el 20 de agosto de 1975 y la Viking 2 el 9 de septiembre de 1975. Las sondas fueron esterilizadas antes del lanzamiento para evitar la contaminación de Marte con organismos de la Tierra. La nave espacial pasó casi un año navegando hacia Marte. La Viking 1 alcanzó la órbita de Marte el 19 de junio de 1976; la Viking 2 comenzó a orbitar Marte el 7 de agosto de 1976.

Después de estudiar las fotografías del orbitador, el equipo de certificación del sitio de aterrizaje de Viking consideró que el lugar de aterrizaje original de Viking 1 no era seguro. El equipo examinó los sitios cercanos y Viking 1 aterrizó el 20 de julio de 1976 en la ladera occidental de Chryse Planitia (las llanuras de oro) a 22,3° de latitud norte y 48,0° de longitud.

El equipo de certificación del sitio también decidió que el lugar de aterrizaje planeado para Viking 2 no era seguro después de examinar fotografías de alta resolución. La certificación de un nuevo lugar de aterrizaje se llevó a cabo a tiempo para un aterrizaje en Marte el 3 de septiembre de 1976, en Utopia Planitia, a 47,7° de latitud norte y 225,8° de longitud.

La misión Viking estaba prevista para continuar durante 90 días después del aterrizaje. Cada orbitador y módulo de aterrizaje funcionó mucho más allá de su vida útil prevista. El Viking Orbiter 1 superó los cuatro años de operaciones de vuelo activas en la órbita de Marte.

La misión principal del proyecto Viking finalizó el 15 de noviembre de 1976, 11 días antes de la conjunción superior de Marte (su paso por detrás del Sol). Después de la conjunción, a mediados de diciembre de 1976, los controladores restablecieron las operaciones de telemetría y comando y comenzaron las operaciones de la misión extendida.

La primera nave espacial que dejó de funcionar fue la Viking Orbiter 2 el 25 de julio de 1978; la nave espacial había utilizado todo el gas de su sistema de control de actitud, que mantenía los paneles solares de la nave apuntando al Sol para alimentar el orbitador. Cuando la nave espacial se alejó de la línea del Sol, los controladores del JPL enviaron órdenes para apagar el transmisor de la Viking Orbiter 2.

En 1978, la Viking Orbiter 1 empezó a quedarse sin gas para el control de actitud, pero gracias a una cuidadosa planificación para conservar el suministro restante, los ingenieros descubrieron que era posible seguir adquiriendo datos científicos a un nivel reducido durante otros dos años. El suministro de gas finalmente se agotó y la Viking Orbiter 1 dejó de funcionar el 7 de agosto de 1980, después de 1.489 órbitas alrededor de Marte.

Los últimos datos de la sonda Viking Lander 2 llegaron a la Tierra el 11 de abril de 1980. La sonda Lander 1 realizó su última transmisión a la Tierra el 11 de noviembre de 1982. Los controladores del JPL intentaron, sin éxito, durante otros seis meses y medio recuperar el contacto con la sonda Viking Lander 1. La misión finalizó el 21 de mayo de 1983.

Con una sola excepción (los instrumentos sísmicos), los instrumentos científicos adquirieron más datos de los esperados. El sismómetro de la sonda Viking Lander 1 no funcionó después del aterrizaje y el sismómetro de la sonda Viking Lander 2 detectó solo un evento que pudo haber sido sísmico. Sin embargo, proporcionó datos sobre la velocidad del viento en el lugar de aterrizaje para complementar la información del experimento meteorológico y mostró que Marte tiene un fondo sísmico muy bajo.

Los tres experimentos de biología descubrieron una actividad química inesperada y enigmática en el suelo marciano, pero no aportaron pruebas claras de la presencia de microorganismos vivos en el suelo cercano a los lugares de aterrizaje. Según los biólogos de la misión, Marte se autoesteriliza. Creen que la combinación de la radiación ultravioleta solar que satura la superficie, la extrema sequedad del suelo y la naturaleza oxidante de la química del suelo impiden la formación de organismos vivos en el suelo marciano. La cuestión de si hubo vida en Marte en algún momento del pasado lejano sigue abierta.

Los instrumentos de cromatografía de gases y espectrómetro de masas de los módulos de aterrizaje no detectaron ningún signo de química orgánica en ninguno de los dos lugares de aterrizaje, pero sí proporcionaron un análisis preciso y definitivo de la composición de la atmósfera marciana y encontraron elementos traza no detectados anteriormente. Los espectrómetros de fluorescencia de rayos X midieron la composición elemental del suelo marciano.

La sonda Viking midió las propiedades físicas y magnéticas del suelo. A medida que descendían hacia la superficie, también midieron la composición y las propiedades físicas de la atmósfera superior marciana.

Los dos módulos de aterrizaje monitorizaron continuamente el tiempo en los lugares de aterrizaje. El tiempo en pleno verano marciano era repetitivo, pero en otras estaciones se volvía variable y más interesante. Aparecieron variaciones cíclicas en los patrones meteorológicos (probablemente el paso de ciclones y anticiclones alternos). Las temperaturas atmosféricas en el lugar de aterrizaje sur (Viking Lander 1) fueron tan altas como -14 °C (7 °F) al mediodía, y la temperatura de verano antes del amanecer fue de -77 °C (-107 °F). En contraste, las temperaturas diurnas en el lugar de aterrizaje norte (Viking Lander 2) durante las tormentas de polvo de mediados de invierno variaron tan poco como 4 °C (7 °F) algunos días. La temperatura más baja antes del amanecer fue de -120 °C (-184 °F), aproximadamente el punto de congelación del dióxido de carbono. Una fina capa de escarcha de agua cubría el suelo alrededor de Viking Lander 2 cada invierno.

La presión barométrica varía en cada lugar de aterrizaje cada seis meses, porque el dióxido de carbono, el principal componente de la atmósfera, se congela formando un inmenso casquete polar, alternativamente en cada polo. El dióxido de carbono forma una gran capa de nieve y luego se evapora de nuevo con la llegada de la primavera en cada hemisferio. Cuando el casquete polar sur era más grande, la presión media diaria observada por la Viking Lander 1 era tan baja como 6,8 milibares; en otras épocas del año era tan alta como 9,0 milibares. Las presiones en el lugar de aterrizaje de la Viking Lander 2 fueron de 7,3 y 10,8 milibares. (A modo de comparación, la presión superficial en la Tierra a nivel del mar es de unos 1.000 milibares).

Los vientos marcianos suelen soplar más lentamente de lo esperado. Los científicos habían esperado que alcanzaran velocidades de varios cientos de kilómetros por hora a partir de las tormentas de polvo globales observadas, pero ninguno de los módulos de aterrizaje registró ráfagas superiores a los 120 kilómetros por hora y las velocidades medias fueron considerablemente inferiores. No obstante, los orbitadores observaron más de una docena de pequeñas tormentas de polvo. Durante el primer verano austral se produjeron dos tormentas de polvo globales, con una diferencia de unos cuatro meses terrestres. Ambas tormentas oscurecieron el Sol en los lugares de aterrizaje durante un tiempo y ocultaron la mayor parte de la superficie del planeta a las cámaras de los orbitadores. Los fuertes vientos que provocaron las tormentas soplaron en el hemisferio sur.

Las fotografías tomadas desde los módulos de aterrizaje y los orbitadores superaron las expectativas en cuanto a calidad y calidad. El total superó las 4.500 tomadas desde los módulos de aterrizaje y las 52.000 tomadas desde los orbitadores. Los módulos de aterrizaje proporcionaron la primera mirada de cerca a la superficie, monitorearon las variaciones en la opacidad atmosférica a lo largo de varios años marcianos y determinaron el tamaño medio de los aerosoles atmosféricos. Las cámaras de los orbitadores observaron terrenos nuevos y a menudo desconcertantes y proporcionaron detalles más claros sobre características conocidas, incluidas algunas observaciones en color y estéreo. Los orbitadores de Viking cartografiaron el 97 por ciento de la superficie marciana.

Los cartografiadores térmicos infrarrojos y los detectores de agua atmosférica de los orbitadores adquirieron datos casi a diario, observando el planeta en baja y alta resolución. La enorme cantidad de datos de los dos instrumentos requerirá un tiempo considerable para el análisis y la comprensión de la meteorología global de Marte. Viking también determinó definitivamente que el manto de hielo residual del polo norte (que sobrevive al verano boreal) es hielo de agua, en lugar de dióxido de carbono congelado (hielo seco) como se creía anteriormente.

El análisis de las señales de radio de los módulos de aterrizaje y los orbitadores (incluidos los datos Doppler, de distancia y de ocultación, y la intensidad de la señal del enlace de retransmisión entre el módulo de aterrizaje y el orbitador) proporcionó una variedad de información valiosa.

Otros descubrimientos importantes de la misión Viking incluyen:

- La superficie marciana es un tipo de arcilla rica en hierro que contiene una sustancia altamente oxidante que libera oxígeno cuando se moja.

- La superficie no contiene moléculas orgánicas detectables a nivel de partes por mil millones: menos, de hecho, que las muestras de suelo traídas de la Luna por los astronautas del Apolo.

- El nitrógeno, nunca antes detectado, es un componente significativo de la atmósfera marciana, y el enriquecimiento de los isótopos más pesados de nitrógeno y argón en relación con los isótopos más ligeros implica que la densidad atmosférica era mucho mayor que en el pasado distante.

- Los cambios en la superficie marciana se producen con extrema lentitud, al menos en los lugares de aterrizaje de la sonda Viking. Durante la duración de la misión, solo se produjeron unos pocos cambios menores.

- La mayor concentración de vapor de agua en la atmósfera se da cerca del borde del casquete polar norte a mediados del verano. Desde el verano hasta el otoño, la concentración máxima se desplaza hacia el ecuador, con una disminución del 30 por ciento en la abundancia máxima. En el verano austral, el planeta está seco, probablemente también como efecto de las tormentas de polvo.

- La densidad de ambos satélites de Marte es baja (unos dos gramos por centímetro cúbico), lo que implica que se originaron como asteroides capturados por la gravedad de Marte. La superficie de Fobos está marcada por dos familias de estrías paralelas, probablemente fracturas causadas por un gran impacto que casi pudo haber destrozado a Fobos.

- Las mediciones del tiempo de ida y vuelta de las señales de radio entre la Tierra y la sonda Viking, realizadas mientras Marte se encontraba más allá del Sol (cerca de las conjunciones solares), han determinado que el retraso de las señales es causado por el campo gravitatorio del Sol. El resultado confirma la predicción de Albert Einstein con una precisión estimada del 0,1 por ciento, veinte veces mayor que cualquier otra prueba.

- La presión atmosférica varía un 30 por ciento durante el año marciano porque el dióxido de carbono se condensa y sublima en los casquetes polares.

- La capa norte permanente es hielo de agua; la capa sur probablemente retiene algo de hielo de dióxido de carbono durante el verano.

- El vapor de agua es relativamente abundante sólo en el extremo norte durante el verano, pero el agua subterránea (permafrost) cubre gran parte, si no todo, del planeta.

- Los hemisferios norte y sur son drásticamente diferentes climáticamente, debido a las tormentas de polvo globales que se originan en el sur en verano.

https://solarviews-com.translate.goog/span/vikingfs.htm?_x_tr_sl=en&_x_tr_tl=es&_x_tr_hl=es&_x_tr_pto=sc |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

24 a 38 de 38

Siguiente Anterior

24 a 38 de 38

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

Traditional clothing of the Knights Templar

Traditional clothing of the Knights Templar Burning of the Knights Templar

Burning of the Knights Templar Image of the Jomsvikings, by Gerhard Munthe, 1899.

Image of the Jomsvikings, by Gerhard Munthe, 1899.