Whisper of the Fifth Sun

Something Wonderful Happening...

May 05, 2009

by Goro (goroadachi.com & supertorchritual.com)

[photo source: cropcircleconnector.com]

Crop Circle

Roundway Hill, Wiltshire, England

April 29, 2009

Down the galactic rabbit hole...

[Battlestar Galactica episodes 'Eye of Jupiter' & 'Rapture']

'Galactica' => Galactic

[Dark Horse Nebula at Ophiuchus' 'big foot']

| . |

'Eye of Jupiter' (BSG):

Religious artifact left by '13th tribe' (split from other 12 tribes) |

Ophiuchus:

So-called '13th sign of Zodiac' (split from traditional 12 signs) |

|

|

| Eye of Jupiter |

Ophiuchus |

| . |

* * *

Ophiuchus/Dark Horse Sequence

| Dec 14, '08: |

Sun at Ophiuchus 'big foot' (Dark Horse Nebula); major shoe/foot incident in Iraq |

| Dec 15, '08: |

Nickelback releases music video (for 1st single) & 2nd single from 'Dark Horse' album |

| April 5/6, '09: |

Italy earthquake (about 300 dead) |

| April 18/19: |

Madonna falls from horse; 21 horses die in Florida before polo match |

| April 29: |

'Eye of Jupiter' Galactic crop circle |

| May 02: |

Dark horse wins Kentucky Derby |

December 14, 2008

Sun at Ophiuchus 'big foot' & major shoe/foot incident in Iraq

Dec 14 Shoes thrown at Bush on Iraq trip

Dec 14 Angry Iraqi throws shoes at Bush in Baghdad

Next day...

December 15, 2008

Nickelback releases music video for 1st single

'Gotta Be Somebody' (& 2nd single 'Something in Your Mouth') from their 'Dark Horse' album

'Gotta Be Somebody' music video 'predicting'

earthquake in Italy/Rome...

Italy = Big foot/leg/boot country

April 5-6, 2009

Italy (L'Aquila) earthquake near Rome (~300 dead)

'Gotta Be Somebody' crossing over into reality

Time mirroring via Venus (Amor/Roma)

Ground zero = L'Aquila

In Roman mythology Aquila is Jupiter's companion eagle

...flying in Milky Way Galaxy

...which is 'Eye of Jupiter'

2 weeks later...

April 18-19, 2009

Dark horse omens

Apr 18 Madonna injured in horse tumble

Apr 19 21 polo horses mysteriously dead in Florida

etc.

10 days later...

April 29, 2009

'Eye of Jupiter/Dark Horse' crop circle

3 days later...

May 02, 2009

'Dark horse' wins Kentucky Derby

May 02 From worst to 1st: 50-1 shot shocks Derby field

dark horse - noun: a racehorse, competitor, etc., about whom little is known or who unexpectedly wins.

* * *

Mayan Prophecy

2012

'End' of Mayan calendar/age...

...popularly associated with 'Galactic Alignment'

(winter solstice at Galactic Equator)

(1998) |

(2002) |

In reality alignment most precise around May 1998

...producing Midpoint around end of August 2005

Hurricane Katrina/New Orleans

'Great Flood' (Deep Impact)

As above, so below...

Milky Way Galaxy = (traditionally) celestial great flood

Then...

Quarter point in April 2009

Early April:

'Galactic' quake disaster in Italy/Aquila

Late April 2009:

- Swine flu outbreak starting in Mexico or land of Maya

- Eye of Jupiter'/Galactic crop circle (Apr 29)

* * *

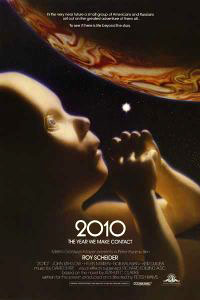

2010

'Eye of Jupiter' = supernova (exploding star)

in Battlestar Galactica 'Rapture'

[Eye of Jupiter nova - video clip]

Echoing...

Jupiter exploding into star in 2010: The Year We Make Contact

| Video clip - '2010' Jupiter explosion |

| |

- Jupiter is fifth planet from Sun

- We are at end of Mayan 'Fifth Sun' (world age)

2010 Winter Olympic Games

in Vancouver, Canada

...featuring 'Bigfoot' mascot

Interacting with Dark Horse...

...of Nickelback

...who are Canadian band based in Vancouver

...where Olympics will starts on February 12th

...mirroring St. Anthony Day Bigfoot press conference (Aug 15)

Let the Games Begin.

.

APPENDIX

The Foresight Files

Key patterns accurately projected beforehand (including Ophiuchus 'big foot'/Iraq shoes, Italy earthquake/Nickelback, , Kentucky Derby, etc.)

T-minus 37 days...

|

Major quake? Death of the Pope/Primate? ... Remember Nickelback's latest music video? ... Earthquake in Rome...

... all the indications are that something big is coming around late March. A straightforward interpretation would be that it's going to involve Italy/Rome/Pope (death?), major earthquake, war, and/or such things.

[excerpt from February 28, 2009 post]

|

[Appendix CONTINUED...]