The invasion of occupied France on D-Day, June 6, 1944, changed the course of the Second World War. Astronomy played a crucial role in the timing of the event.

This month marks the 75th anniversary of the D‑Day invasion of Normandy, France. But why was June 6th chosen? Astronomy played a role: The Moon and Sun affected the planning and the selection of this date.

Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate Robert F. Sargent captured this famous D Day image of the scene on Omaha Beach at about 7:40 a.m.

Coast Guard Chief Photographer’s Mate Robert F. Sargent captured this famous D Day image of the scene on Omaha Beach at about 7:40 a.m.U.S. Coast Guard, Department of Defense

Did the airborne divisions want the darkness of a new Moon or the brightness of a full Moon when the paratroopers began parachuting into France just after midnight? And how did planners coordinate that lunar phase with the requirement for a low tide near sunrise, so that engineers could destroy exposed beach obstacles before the landing craft of the main assault waves came in?

Invasion of Europe

In the early morning hours of June 6, 1944, the complex operation code-named Overlord began to unfold. The Allies had assembled an armada of 5,000 ships and landing craft carrying 130,000 soldiers across the English Channel to the Normandy beaches. Airborne operations carried a total of 24,000 troops using more than a thousand transports and gliders. Near sunrise, aerial and naval bombardment shook the German coastal strongpoints, and landing craft started the long runs in to the beaches.

Any invasion date in May or June would leave the entire summer for the Allied drive across France and toward the German homeland before bad weather in fall or winter could slow the advance. But the invasion planners later made clear that the selection of June 6th in particular was for astronomical reasons: moonlight and the effects of the lunar phase on the tides came into play. The Allies required a low tide near sunrise, and, on this part of the Normandy coast, such a tide occurs only near the times of either new Moon or full Moon.

Moon, Sun, and Tides

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Allied Supreme Commander, realized that preparations were not complete in May and postponed the assault until June. His 1948 book, Crusade in Europe, explained why moonlight and a low tide were important:

...the next combination of moon, tide, and time of sunrise that we considered practicable for the attack occurred on June 5, 6, and 7 …We wanted a moon for our airborne assaults … We had to attack on a relatively low tide because of beach obstacles which had to be removed while uncovered.

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, in his 1960 memoir The Great Sea War, likewise recalled the significance of the lunar phase and the tide times:

... staff … desired a moonlit night preceding D-day so that the airborne divisions would be able to organize and reach their assigned objectives before sunrise… the tide … must be rising at the time of the initial landings so that the landing craft could unload and retract without danger of stranding…Yet the tide had to be low enough that underwater obstacles could be exposed for demolition parties.

This publicity photograph from the 1962 film, The Longest Day, shows the early assault waves advancing on foot through mined beach obstacles, a mixture of stakes and hedgehogs.

This publicity photograph from the 1962 film, The Longest Day, shows the early assault waves advancing on foot through mined beach obstacles, a mixture of stakes and hedgehogs.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, in his 1951 book Closing the Ring, stressed the astronomical and tidal factors:

Only on three days in each lunar month were all the desired conditions fulfilled. The first three-day period...was June 5, 6, and 7…If the weather were not propitious on any of those three days, the whole operation would have to be postponed at least a fortnight—indeed, a whole month if we waited for the moon.

The Allies initially intended to invade on June 5th, but bad weather forced a postponement of one day.

Calculating the Effects of Moon and Sun

A nearly full Moon rose 1½ hours before sunset on June 5th, reaching its highest point on June 6th at 1:19 a.m., just as the American airborne assault began. Slanting moonlight illuminated the ground below for the troops of the 82nd and the 101st Airborne as they started dropping from the sky between 1:15 and 1:30 a.m., following pathfinders who had jumped about an hour earlier. These times are expressed in British Double Summer Time (two hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time), as employed by the Allied invasion forces.

Brigadier General James Gavin of the 82nd Airborne provided an eyewitness account in a 1947 monograph titled Airborne Warfare. As his C‑47 aircraft approached a drop zone west of Sainte-Mère-Église, Gavin could clearly see the ground below:

…the roads and the small clusters of houses in the Normandy villages stood out sharply in the moonlight.

Importance of the Tides

The German defenders had employed several types of mined obstacles on the beaches, as shown in the accompanying illustrations.

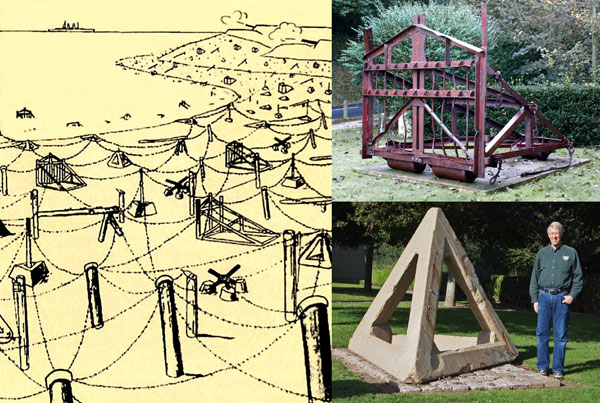

Left: This German plan of beach obstacles shows barbed wire connecting stakes, ramps, hedgehogs, Belgian Gates, and tetrahedrons, as the beach would appear near low tide. Upper right: This Belgian Gate beach obstacle is preserved at the Omaha Beach Memorial Museum in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Lower right: Don Olson poses with a tetrahedron beach obstacle in the collection of the Battle of Normandy Memorial Museum in Bayeux.

Left: This German plan of beach obstacles shows barbed wire connecting stakes, ramps, hedgehogs, Belgian Gates, and tetrahedrons, as the beach would appear near low tide. Upper right: This Belgian Gate beach obstacle is preserved at the Omaha Beach Memorial Museum in Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer. Lower right: Don Olson poses with a tetrahedron beach obstacle in the collection of the Battle of Normandy Memorial Museum in Bayeux.Upper right: © John Hamill; Lower right: Marilynn Olson

General Omar Bradley described in his 1951 memoir A Soldier’s Story how the plans for the demolition teams depended on the tides:

At low tide the beach defenses lay exposed … We would assault when a rising tide reached the obstacle line and give the engineers 30 minutes to clear it before the water became too deep. Successive assault waves would then ride the rising tide nearer the sea wall through gaps in the obstacle belt.

Tide Calculations for Omaha Beach

Our Texas State group wrote a computer program to calculate the tide levels at Omaha Beach. The calculated morning tide range was about 18 feet, with a rapid rise from low water at 5:23 a.m. to high water at 10:12 a.m.

The 150mm guns of the German battery at Longues-sur-Mer were located near the coast between Omaha Beach and Gold Beach. Members of the Texas State group pictured here are Laura Bright, Don Olson, and Hannah Reynolds.

The 150mm guns of the German battery at Longues-sur-Mer were located near the coast between Omaha Beach and Gold Beach. Members of the Texas State group pictured here are Laura Bright, Don Olson, and Hannah Reynolds.Russell Doescher

This rapid rise had a significant effect. The initial landings at Omaha Beach took place at 6:30 a.m. Over the next 30 minutes, the water level rose 2.4 feet as the demolition teams struggled to place explosives while the obstacles were still exposed. By 7 a.m. the water level was already rising by one foot every 10 minutes, and that rate only accelerated. Even a small delay had serious consequences. These calculations help explain why demolition crews cleared only five of the planned 16 gaps among the obstacles before the advancing tide forced them to wade ashore.

While tidal and astronomical considerations meant that the date of the Normandy invasion had to fall near a full Moon, its gravitational effects were then responsible for the rapidly rising spring tide. The remaining fields of mined beach obstacles contributed to the loss of momentum of the following assault waves and helped earn Omaha Beach its nickname: “Bloody Omaha.”

D-Day Timetable

The five landing beaches had the code names Utah (American forces), Omaha (American), Gold (British), Juno (Canadian), and Sword (British), in order from west to east. Astronomical calculations are for the Caen Canal and Orne River bridges near Bénouville, France (49° 15' North Latitude, 0° 16' West Longitude), just inland from Sword Beach. The times are expressed in British Double Summer Time (two hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time), as employed by the Allied invasion forces.

June 5, 1944

8:30 p.m. Moonrise, Moon is 99% lit

10:01 p.m. Sunset

June 6, 1944

12:16 a.m. First British glider lands at the Caen Canal bridge, bright Moon in southeastern sky

12:26 a.m. Radio message sent: British captured the canal bridge and Orne River bridge intact

1:15 a.m. American paratroopers begin to land inland from Utah Beach

1:19 a.m. Lunar transit, Moon at its highest point in the sky for the night

5:17 a.m. Beginning of civil twilight

5:23 a.m. Low water exposes the beach obstacles on Omaha Beach

5:50 a.m. Naval bombardment of Omaha Beach begins

5:57 a.m. Sunrise

6:02 a.m. Moonset, Moon is 99% lit

6:30 a.m. First assault wave lands on Omaha Beach, on a rising tide

7:25 a.m. First assault wave lands on Sword Beach, on a rising tide

10:12 a.m. High water covers Omaha Beach almost to the sea wall

1:00 p.m. Approximate time when Lord Lovat leads British commandos inland from Sword Beach and they link up with the airborne forces at the canal bridge

Moon over Pegasus Bridge

Six hours before the amphibious landings even began, British soldiers carried on gliders had already descended silently from the night skies and landed on French soil. Their objectives were two crucial bridges over two parallel waterways, the Caen Canal and the Orne River, just inland from Sword Beach. A bright Moon was crucial for this assault.

At 10:56 p.m. on June 5th at Tarrant Rushton airfield in England, the engines of the massive Halifax bombers serving as tugs surged from a steady hum to a deafening roar. Within minutes six gliders had been pulled into the air. In the moonlight over England, the aircraft formed up and headed out for the flight over the Channel.

The British employed six Airspeed Horsa gliders to land the assault forces near the Caen Canal and Orne River bridges. This full-size Horsa replica, built according to the original wartime glider plans, was unveiled at the Memorial Pegasus museum in 2004 for the 60th anniversary of D-Day.

The British employed six Airspeed Horsa gliders to land the assault forces near the Caen Canal and Orne River bridges. This full-size Horsa replica, built according to the original wartime glider plans, was unveiled at the Memorial Pegasus museum in 2004 for the 60th anniversary of D-Day.Amanda Slater

James Wallwork, pilot of the lead glider, realized when his tug had reached France, because in the moonlight he could see the surf breaking on the Normandy coastline. Wallwork recalled how he could see the waterways as the Moon shone from between clouds:

And there are the river and canal like silver ribbons in the moonlight.

With pardonable exaggeration, Wallwork described the moonlit scene as his glider approached the canal bridge objective. (The interview can be seen in the film shown at the Memorial Pegasus museum):

I could see the target. The Moon was on it. I could see the bridge. I could see the whites of their eyes almost.

This aerial photograph shows the Memorial Pegasus museum in the distance, the original 1944 Pegasus Bridge in its permanent position on the museum grounds, and the full size Airspeed Horsa glider replica in the foreground. The landing zone for the three British gliders on D-Day is just visible at the extreme upper right.

This aerial photograph shows the Memorial Pegasus museum in the distance, the original 1944 Pegasus Bridge in its permanent position on the museum grounds, and the full size Airspeed Horsa glider replica in the foreground. The landing zone for the three British gliders on D-Day is just visible at the extreme upper right.Michel Dehaye

Wallwork’s glider was the first to land, skidding to a halt near the canal bridge at 12:16 a.m. Two more gliders followed into this landing zone, and the British soldiers quickly overwhelmed the German defenders. The group at the Orne River bridge had similar success, with their descent likewise aided by the moonlight.

The canal bridge became known as “Pegasus Bridge,” a name that refers to the British airborne insignia featuring the mythological “airborne warrior” Bellerophon riding the winged horse Pegasus.

A “Late-rising” Moon?

Many authors writing about D-Day mistakenly imagine that the Allied forces wanted a dark night until the airborne divisions reached their targets. We located the primary source for this mistake in the memoirs of Walter Bedell Smith, one of Eisenhower’s closest aides. Smith’s article for the June 8, 1946, Saturday Evening Post made the erroneous claim that for “the airborne landings … we needed a late-rising full moon, so the pilots could approach their objectives in darkness, but have moonlight to pick out the drop zones.” Cornelius Ryan’s classic 1959 book The Longest Day used Smith as a source, and Ryan wrote that a “critical demand was for a late-rising moon.” A Google search with relevant keywords (D-Day late‑rising Moon) will bring up many subsequent authors who followed Ryan and repeated this unfortunate error regarding a “late‑rising” Moon.

Astronomical calculations show that the Moon was definitely not “late‑rising.” Moonrise actually occurred very early – the Moon had already risen into the sky about 1½ hours before sunset on the preceding day (June 5th). The Moon then remained in the sky during the entire night of June 5th-6th, 1944.

The stone monuments of the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer dominate the foreground of this aerial photograph. The cemetery is located on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach and the English Channel, both seen in the background.

The stone monuments of the American Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer dominate the foreground of this aerial photograph. The cemetery is located on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach and the English Channel, both seen in the background.Michel Dehaye

As the 75th anniversary of D-Day approaches, the commemorations will rightly focus on the heroism of the Allied soldiers, sailors, and airmen who began the liberation of France. Readers of Sky & Telescope can also use this month to recognize the importance of the astronomical factors that determined the date of the invasion and then affected the course of events for both the airborne and amphibious forces on that historic day.

8

8