|

|

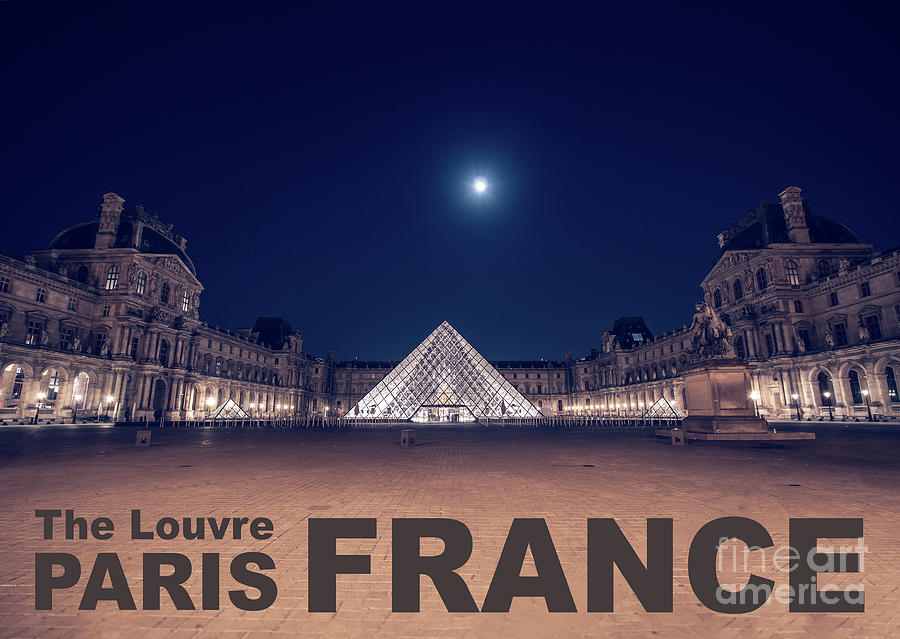

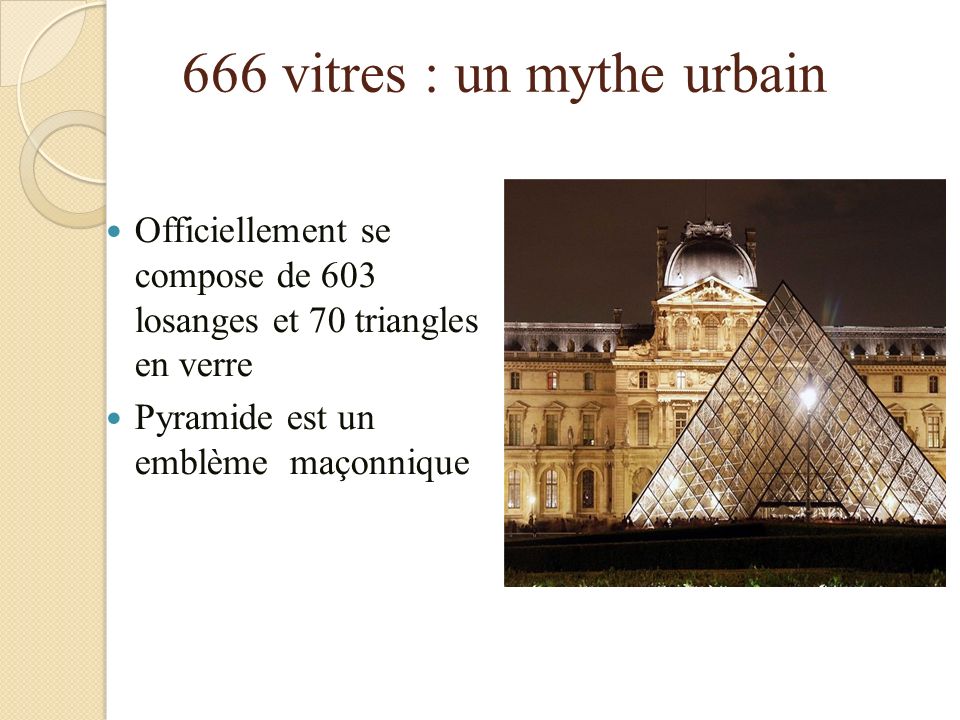

Symbolic Meaning Of The Louvre, Paris France

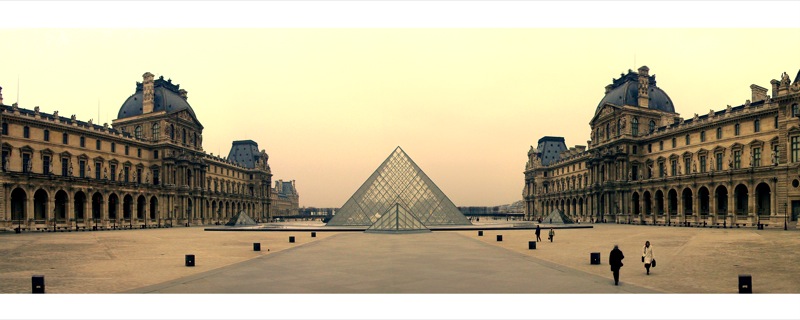

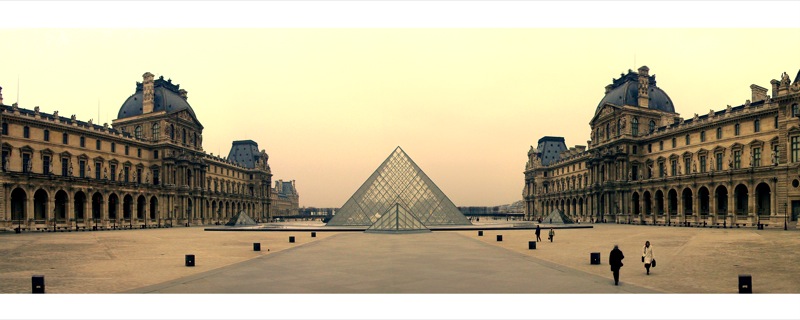

I.M. Pei’s Louvre pyramid connects the vast wings of the museum to one central location. Most of the space is buried underground, keeping the visual attention on the historic palace.

Was Napoleon’s monument to freedom Elephant of the Bastille a factor in the design? Did astrology form the shapes and arrangement? Johann Kepler charted horoscopes using this same form, and related it to profound scientific laws. Gender is also seen by many in the upright and inverse pyramids. The Louvre, in the heart of Paris, fixes all the problems with Modernism. The shocking form fits in because it was derived by careful study and with thoughtful purpose.

A quick walk a modern obelisk, the Eiffel tower, leads to the Arc de Triumph, copied from ancient Rome. A straight line from there leads to an ancient Roman obelisk, and immediately to the Louvre.

|

|

|

I.M. Pei’s 1989 design for the Pyramide du Louvre at the historic Louvre Palace in Paris France starts with architecture’s most significant symbol: the pyramid. A tunnel descends into structure like the ancient pyramids of Egypt.

The museum spans the entire history of mankind, and so the pyramid itself assumes a futuristic character. Its transparent materials achieve this futurism while opening views to the building surrounding it, and opening natural sunlight into the front lobby. A rather ingenious tension structure is holds the pyramid up.

The La Pyramide Inversée inverted pyramid has been made famous by the Da Vinci Code. But this is just one element of this enormous project, which takes more than a week to properly visit.

Procession To Democracy

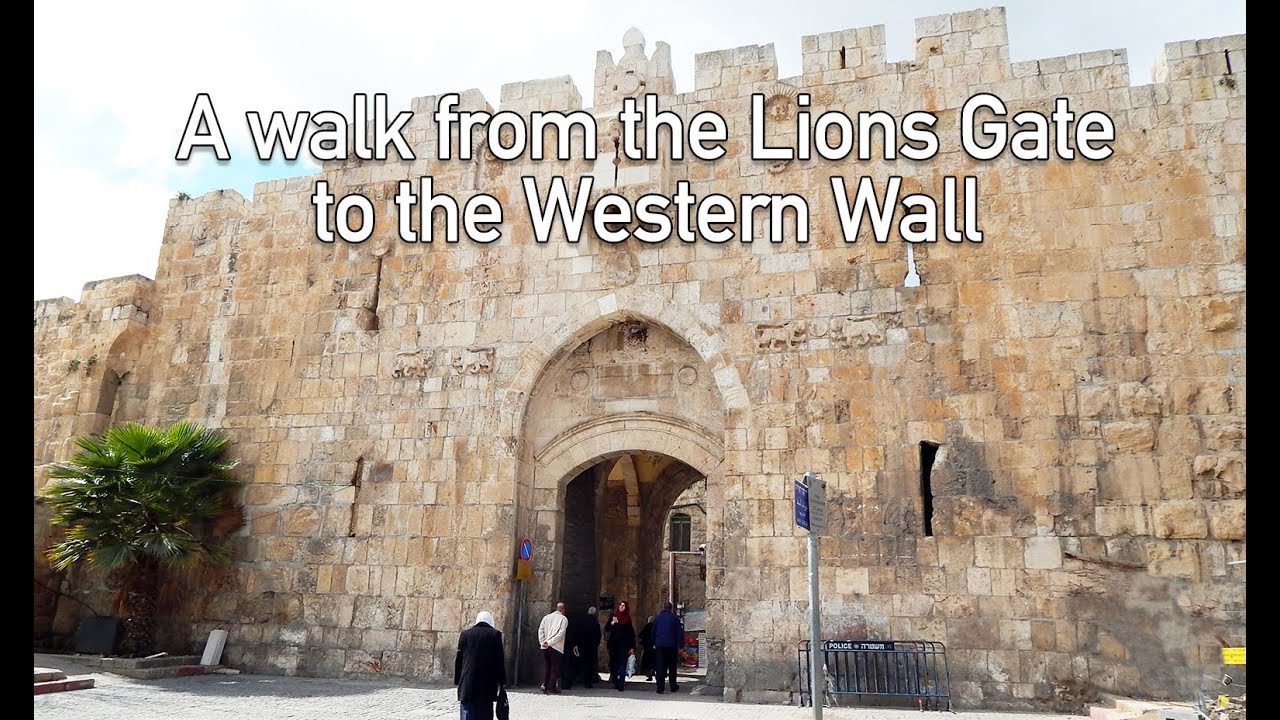

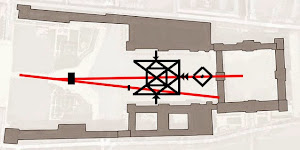

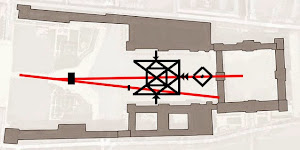

| Pei’s concept sketches show two axis. The first runs through the park to the Arc de Triumph du Carrousel. Here it meets another tilted axis, which continues on into the Louvre. This Axe Historique is the strongest site axis in the world, extending through central Paris to the city’s modern quarter. |

|

|

| This tilting of spaces at the Arc de Triumph and the pyramid keeps the composition unified yet unexpected.

In 1833, a column stood where the pyramid now stands. A third axis tilts slightly as it extends from this point on to the east. This third axis extended to the Place de la Bastillewhere a similar column was constructed in 1835 to commemorate the revolution against King Charles X.

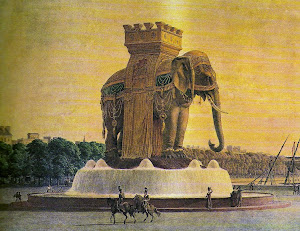

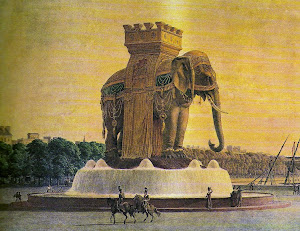

The July column at the Place de la Bastille replaced the Elephant of the Bastille, which gives insight into the meaning of the Louvre pyramid. The Elephant was a large structure atop a fountain, which people could enter through a staircase and walk around inside, as with today’s Louvre pyramid. It was cast in bronze from the guns captured by Napoleon in his conquests. In Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, it housed the homeless children of the Revolution. Run-down and despondant, it symbolized the humility and determination of democracy:

|

|

|

“There it stood in its corner, melancholy, sick, crumbling, surrounded by a rotten palisade, soiled continually by drunken coachmen; cracks meandered athwart its belly, a lath projected from its tail, tall grass flourished between its legs; and, as the level of the place had been rising all around it for a space of thirty years, by that slow and continuous movement which insensibly elevates the soil of large towns, it stood in a hollow, and it looked as though the ground were giving way beneath it. It was unclean, despised, repulsive, and superb, ugly in the eyes of the bourgeois, melancholy in the eyes of the thinker.” -Victor Hugo

The Statue of Liberty in New York is a modern descendant from the Elephant. Visitors walk into and climb a stairway up the Statue, much like in the Elephant. The Louvre Pyramid achieves the same kind of procession, and directly links to its axis in the city. It therefore could assume the symbol of the poor and humble class. The poor gain access to the wealth of the world in the museum. History and art liberates the people.

Astrology

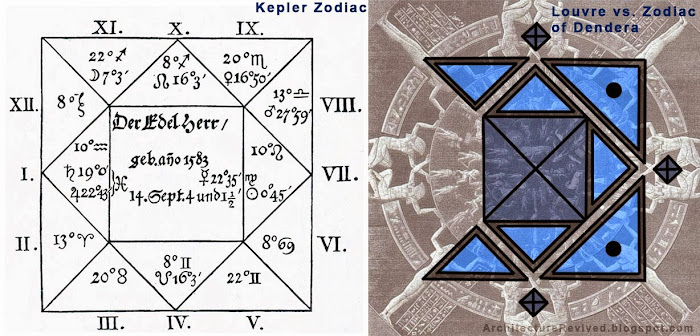

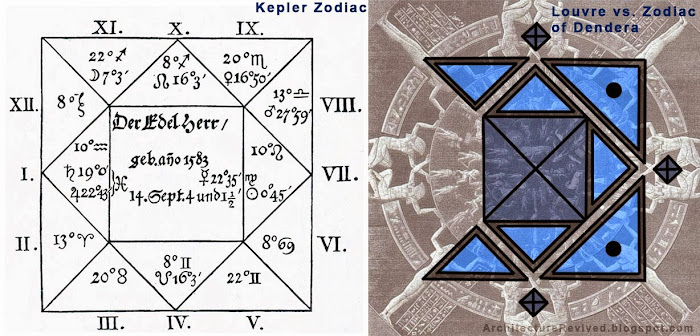

| By 1850, the column in the courtyard was replaced by two circles. Pei’s early sketches start to resemble these two circles. Yet while the inverted pyramid keep a circular outline, the large pyramid is decidedly rectangular. Pei took a square and fit another square inside it. How did Pei get this geometric form? Astronomer Tycho Brahe built the Uraniborg observatory based on the classic chart of the four terrestrial elements. He applied the four states of the four elements (earth, fire, water, air) to the celestial sphere for the first time, asserting a new idea that stars are subject to change like anything else.

Tycho’s assistant, Johann Kepler applied this building form to astrology. His rectangular horoscope used tilted concentric squares that look very similar to Pei’s form at the Loure. If you lay the classic zodiac over the louvre pyramid, you can see how it fits.

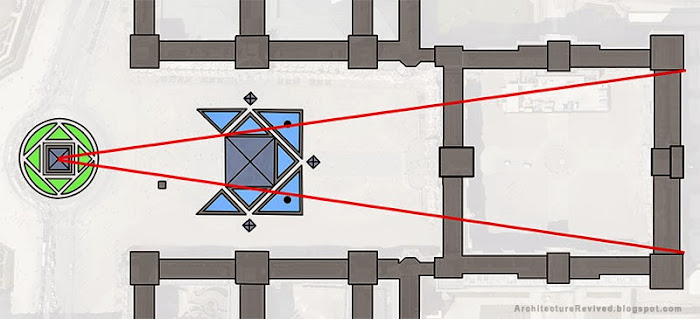

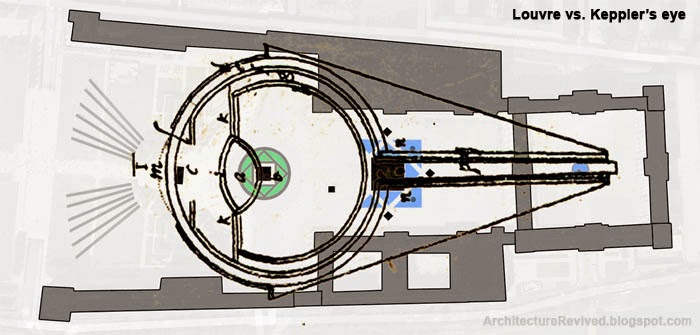

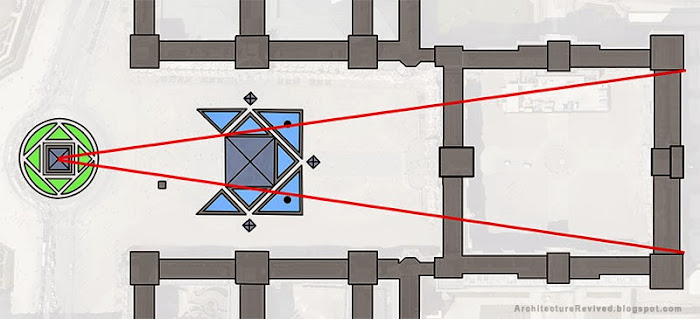

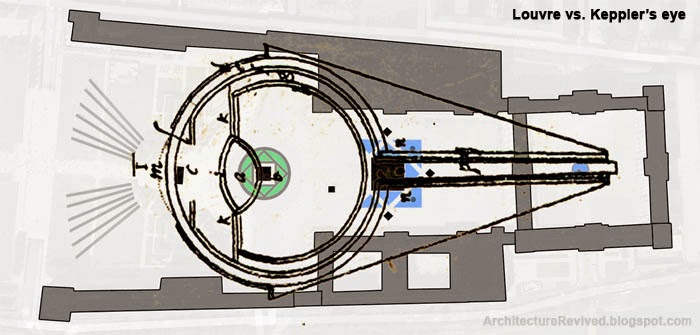

Did Pei look at Kepler’s horoscope for the pyramid entrance to the Louvre? Compare the plan-view of the Louvre entrance with Kepler’s zodiac and the ancient astrology diagram:

|

|

|

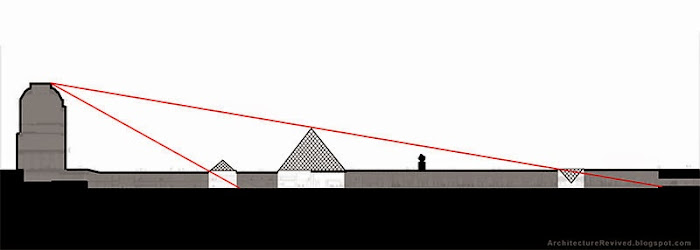

A 90 degree triangle approaches the pyramid from the left side. This T-square aspect pattern forms a trine, which is considered in astrology to be “a source of artistic and creative talent.” This is therefore an appropriate entrance to an art museum. The Louvre’s entrance forms a trine. The 120 degree trine in the musical scale indicates a perfect fifth step, which is the strongest relationship of notes in music. The sun moves almost exactly 120 degrees on the summer solstice in Paris.

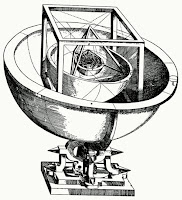

| Kepler fit platonic solids inside each other. The tetrahedron was surrounded by the cube. More complex platonic shapes fit inside the tetrahedron, until finally they formed a sphere. This could be the background for Pei’s pyramid inside the Kepler square. The inverse pyramid fits inside a circle and the large pyramid inside a square.

Pei said he used a pyramid because it was “the most structurally stable of forms.”1 The pyramid is glass so that it is only barely seen, an intellectual suggestion.

|

|

|

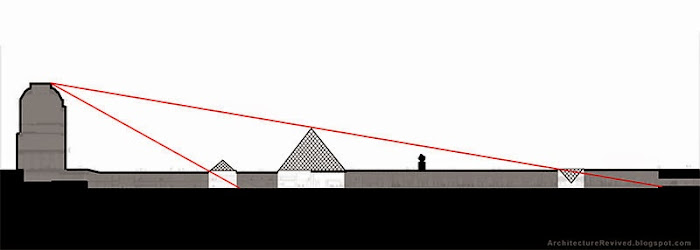

The large pyramid touches a line between the top of the historic palace and the inverse pyramid. Looking at it in plan view, the edge of the large pyramid touches lines between the ends of the palace and the center of the inverse pyramid. These lines of sight suggest calculus that is used to derive perfect solids. They are an intellectual manifestation of perfect forms.

The pyramid and square could be based on Keppler’s laws of planetary motion. Kepler described the harmony of planets, music, poetry, etc. with proportions. Kepler’s third law, that the period of a planet’s orbit squared is proportional to the distance of the orbit cubed, describes the harmony of motion and distance. The pyramid volume is proportional to a line squared, and the cube volume is proportional to a line cubed.

The inverse pyramid’s proportion to its outer circle is the same as the earth’s proportion to the moon (27%). The large pyramid is likewise exactly 27% the width of the courtyard. The front entrance is half that distance from the front of the courtyard. Both pyramids thus relate the size of the moon to the size of the sun.

Kepler applied the mathematics of the perfect platonic solids to the epicycles of planets. Rejecting Ptolemic astronomy, Kepler declared that the earth revolves around the sun, and that the moon revolves around the earth, in elliptical orbits. He related these proportions to various things, such as the structure of the human eye. Indeed, if you overlay Kepler’s drawing of the eyeball over the Louvre, you see that the proportions line up. The Arc de Triumph aligns with the front of the cornea, the inverse pyramid with the lens, and the large pyramid with the front of the optic nerve. The hedges in the park even look like light rays approaching the eye from the left. This is because the harmonic proportions of the Louvre universally describe naturally occurring systems.

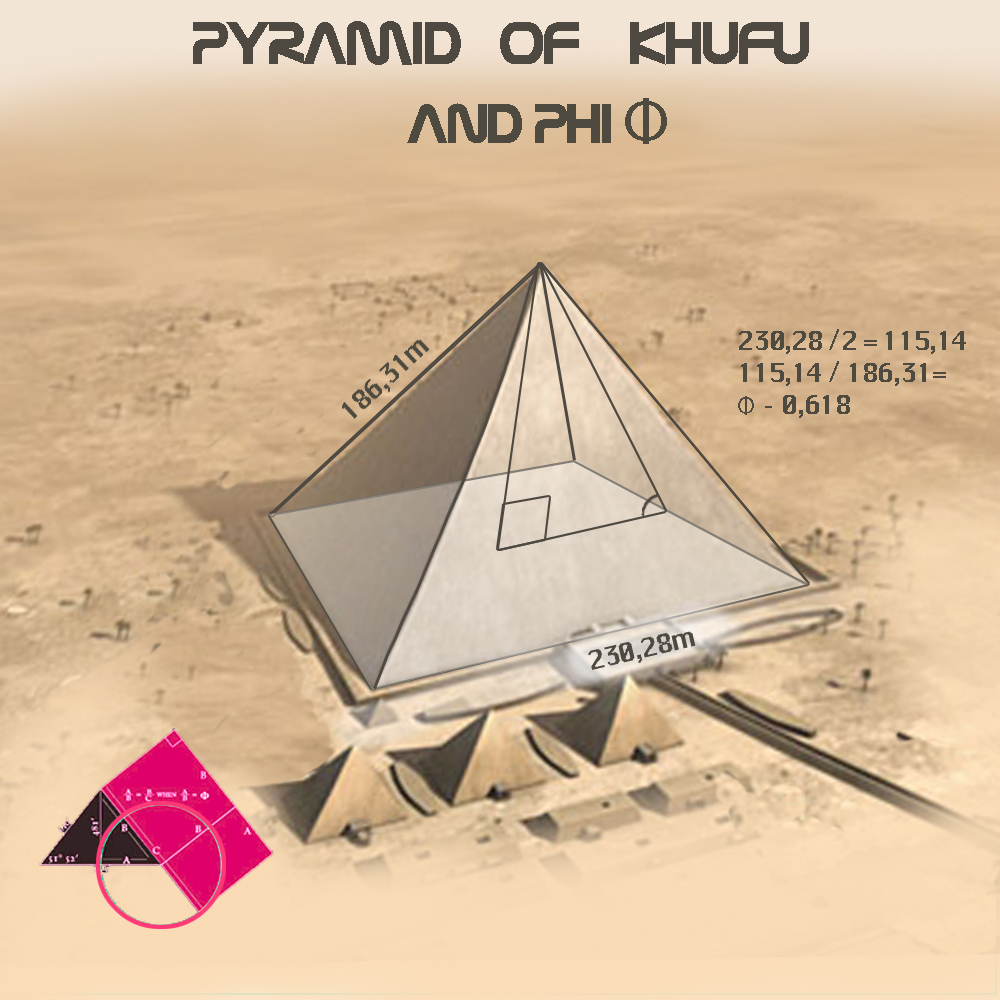

Golden Mean

The pyramid proportionally relates a system of objects, so it is no surprise that the golden mean is a basis for the pyramid’s size. The golden mean determines form and distance. The golden mean determines the pyramid’s size between the front and back, and the left and right of the courtyard. The statue of King Louis XIV, which is the endpoint of the park axis, aligns with this proportion. The golden mean also relates the inverse pyramid to the fountain edge.

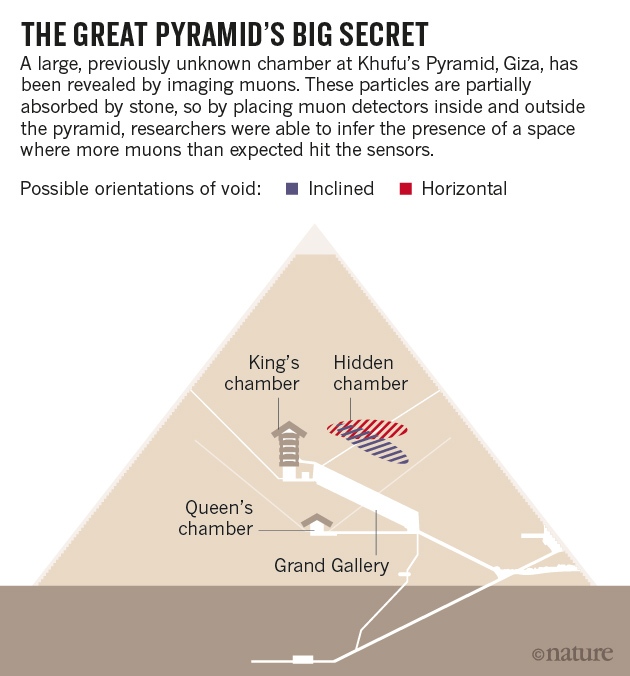

The Louvre pyramid has the same slope as the Great Pyramid in Giza, at 51 degrees. The significance of the golden proportion in the Great Pyramid thus applies to the Louvre. It uses the golden proportion to achieve its form. The procession into the front, descending down into underground also follows the Great Pyramid in Giza.

The summer solstice sun crosses just inside the Arc de Triumph along the Axe Historique as it sets. The sun therefore is of vital importance in this site axis. The setting summer sun establishes a line of site between the statue of King Louis XIV with the inverse pyramid:

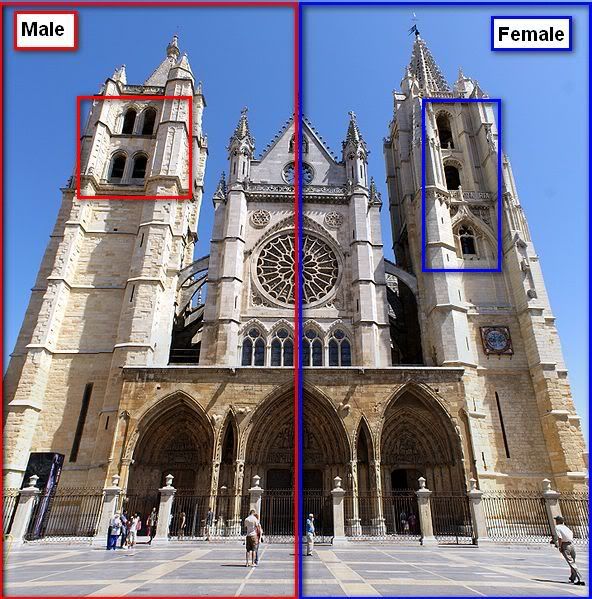

Gender

The circle is traditionally female and the square male. The inverse pyramid thus appears female while the larger upright pyramid is male. Many are aware that the Louvre is a metaphor for the chalice and blade. The chalice is the female aspect of creating life and is represented by an inverse pyramid. The blade is the male aspect of death and is represented by an upright pyramid. This metaphor is strengthened when you consider that the inverse pyramid is surrounding by living grass and the upright pyramid by fluid water. The Egyptians believed the waters of chaos must be crossed in the afterlife, and this is why they placed their funeral upright pyramids near the river Nile. Male/female relate to life/death and circle/square.

The entrance procession continues this gender language of circles and squares. The left spiral staircaseswirls in a circular motion, and on the right side a linear staircase descends in strict right angles. The Louvre’s free-standing staircase is a structural marvel, and its unrestrained circular motion was not easily achieved.

I think this gender symbolism is the most significant thing about the Louvre pyramid. Modernism seems intent on destroying all gender in our architectural language, yet here is a stark example of Modernism pushing ancient gender language. Its subtle power is the stuff of mystery novels, yet it is not really understood.

(rvr– flickr/creative commons license)

Life and death are investigated as the pyramid plays with the idea of above-ground and underground. The water fountains reflect the blue sky on the ground and suggests an inverse relationship. The clear pyramid allows light to fill the subterranean space. Then, at the inverse pyramid, everything flips upside down. The blue fountains take the form of blue sky and the transparent pyramid fills into the building. Rather than the building against a sky, it is the sky against the building. It touches a solid form, a small pyramid, a polar opposite to the unsubstantial sky. The roof of the Louvre palace can barely be seen from the inverse pyramid, a visual connection that brings this dichotomy all together.

This forces the visitor to investigate nature’s opposites. From Keppler’s investigation of natural systems, to perfect proportions, and natural opposite relationships, the Louvre makes the museum visitor investigate natural law.

Massimiliano Fuksas borrowed Pei’s concept of glazed sky intruding into building space. His MyZeil mall in Frankfurt swirls glazing around the public space.

More Info , More Info , Book

(tetraconz– flickr/creative commons license)

(Ivo Jansch– flickr/creative commons license)

(dynamosquito– flickr/creative commons license)

(Carlton Browne– flickr/creative commons license)

(mariosp– flickr/creative commons license)

(mariosp– flickr/creative commons license)

(Guerretto– flickr/creative commons license)

(roryrory– flickr/creative commons license)

(genericface– flickr/creative commons license)

https://www.architecturerevived.com/symbolic-meaning-louvre-paris-france/ |

|

|

|

|

|

LLAVE DE ORO Y DE PLATA AL IGUAL QUE LA MANZANA

Incendio Notre Dame: Última hora de la catedral de París (15 DE ABRIL)

Incendio Notre Dame (París), en directo (Bertrand Guay / AFP)

PHI A NOTRE-DAME

A la catredal de Notre Dame hi observem més rectanlges auris: Creat per Mario Pastor

The DaVinci Code, Notre Dame Cathedral from DaVinci Code

original movie prop

August 23, 2018/

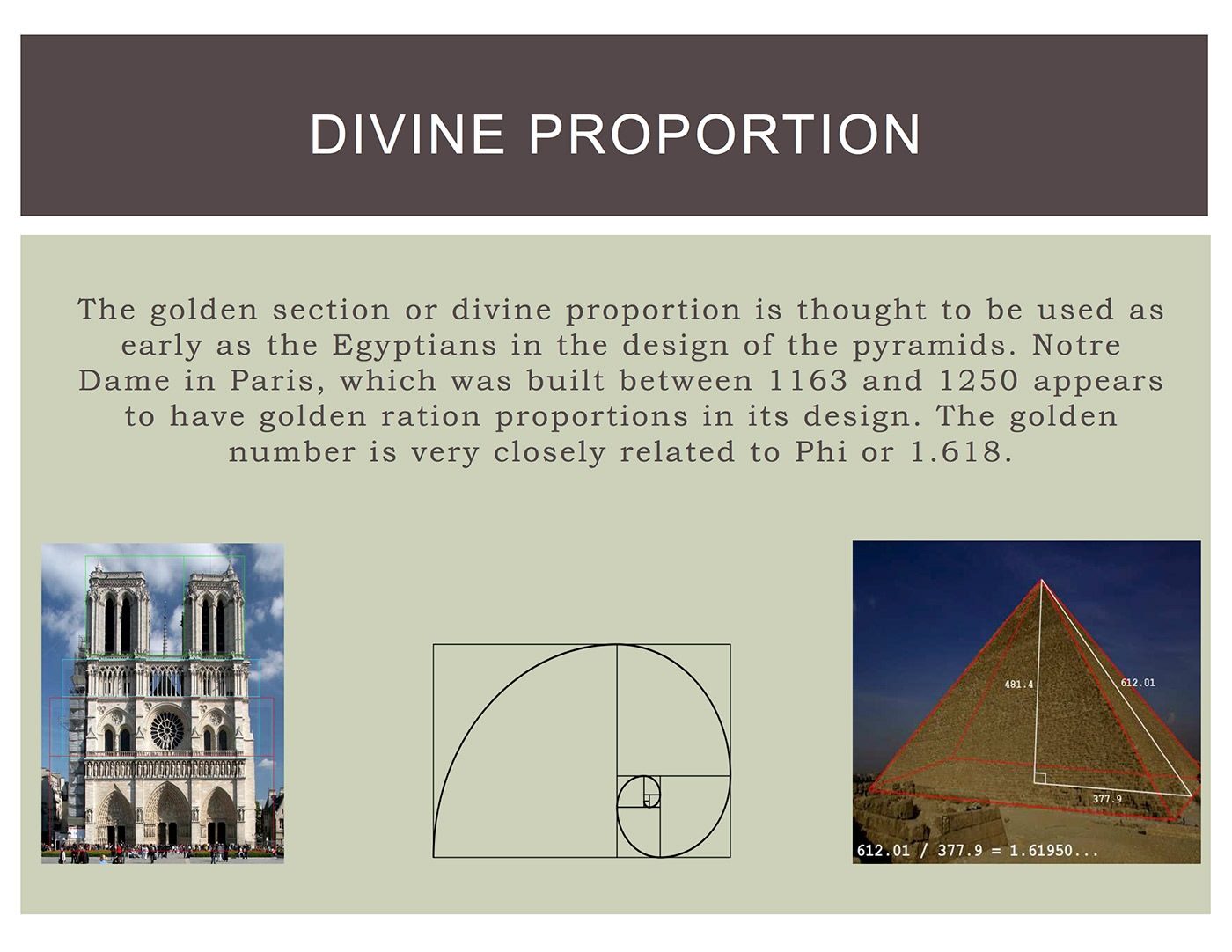

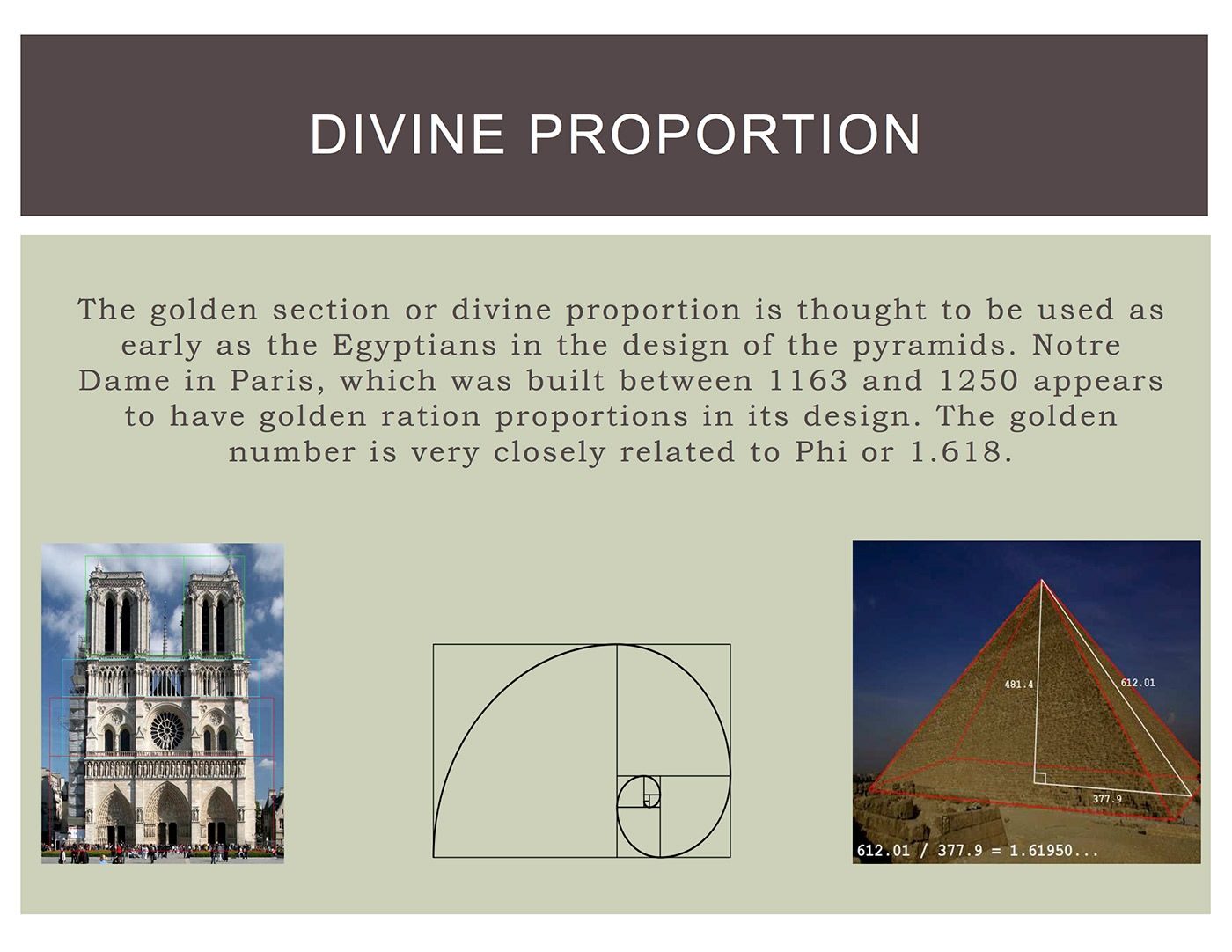

The Golden Section (aka Golden Mean, and Golden Ratio) phys.org

We use math in architecture on a daily basis to solve problems. We use it to achieve both functional and aesthetic advantages. By applying math to our architectural designs through the use of the Golden Section and other mathematical principles, we can achieve harmony and balance. As you will see from some of the examples below, the application of mathematical principles can result in beautiful and long-lasting architecture which has passed the test of time.

Using Math in Architecture for Function and Form

We use math in architecture every day at our office. For example, we use math to calculate the area of a building site or office space. Math helps us to determine the volume of gravel or soil that is needed to fill a hole. We rely on math when designing safe building structures and bridges by calculating loads and spans. Math also helps us to determine the best material to use for a structure, such as wood, concrete, or steel.

“Without mathematics there is no art.” – Luca Pacioli, De divina proportione, 1509

Architects also use math when making aesthetic decisions. For instance, we use numbers to achieve attractive proportion and harmony. This may seem counter-intuitive, but architects routinely apply a combination of math, science, and art to create attractive and functional structures. One example of this is when we use math to achieve harmony and proportion by applying a well-known principle called the Golden Section

Math and Proportion – The Golden Section

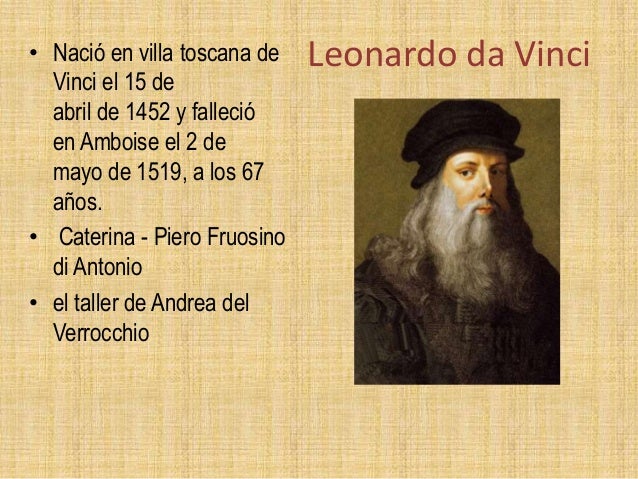

Perfect proportions of the human body – The Vitruvian Man – by Leonardo da Vinci.

We tend to think of beauty as purely subjective, but that is not necessarily the case. There is a relationship between math and beauty. By applying math to our architectural designs through the use of the Golden Section and other mathematical principles, we can achieve harmony and balance.

The Golden Section is one example of a mathematical principle that is believed to result in pleasing proportions. It was mentioned in the works of the Greek mathematician Euclid, the father of geometry. Since the 4th century, artists and architects have applied the Golden Section to their work.

The Golden Section is a rectangular form that, when cut in half or doubled, results in the same proportion as the original form. The proportions are 1: the square root of 2 (1.414) It is one of many mathematical principles that architects use to bring beautiful proportion to their designs.

Examples of the Golden Section are found extensively in nature, including the human body. The influential author Vitruvius asserted that the best designs are based on the perfect proportions of the human body.

Over the years many well-known artists and architects, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, used the Golden Section to define the dimensions and proportions in their works. For example, you can see the Golden Section demonstrated in DaVinci’s painting Mona Lisa and his drawing Vitruvian Man.

Famous Buildings Influenced by Mathematical Principles

Here are some examples of famous buildings universally recognized for their beauty. We believe their architects used math and the principals of the Golden Section in their design:

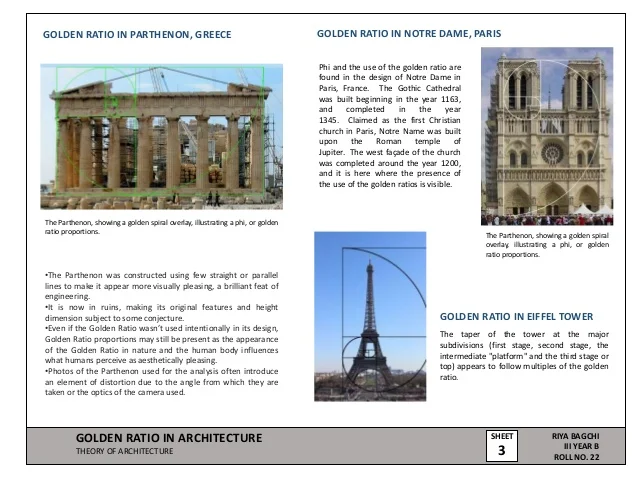

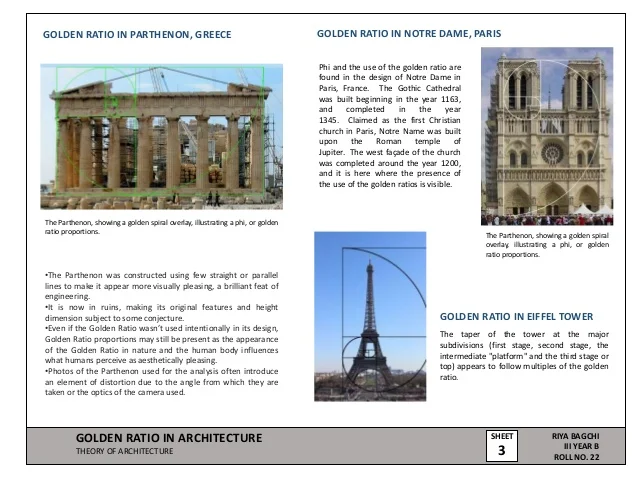

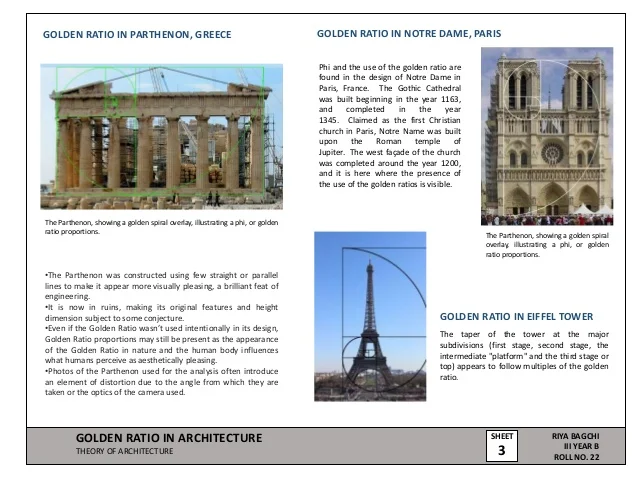

Parthenon

The classical Doric columned Parthenon was built on the Acropolis between 447 and 432 BC. It was designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates. The temple had two rooms to shelter a gold and ivory statue of the goddess Athena and her treasure. Visitors to the Parthenon viewed the statue and temple from the outside. The refined exterior is recognized for its proportional harmony which has influenced generations of designers. The pediment and frieze were decorated with sculpted scenes of Athena, the Gods, and heroes.

Parthenon Golden Section

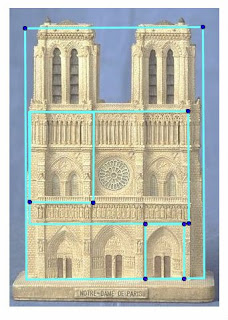

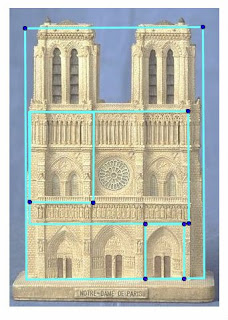

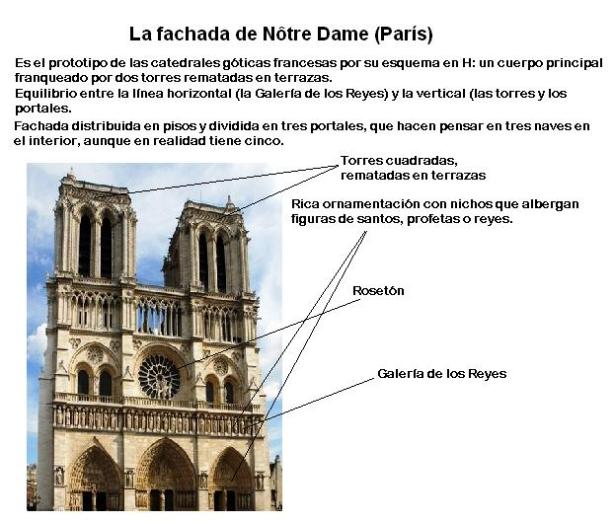

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris

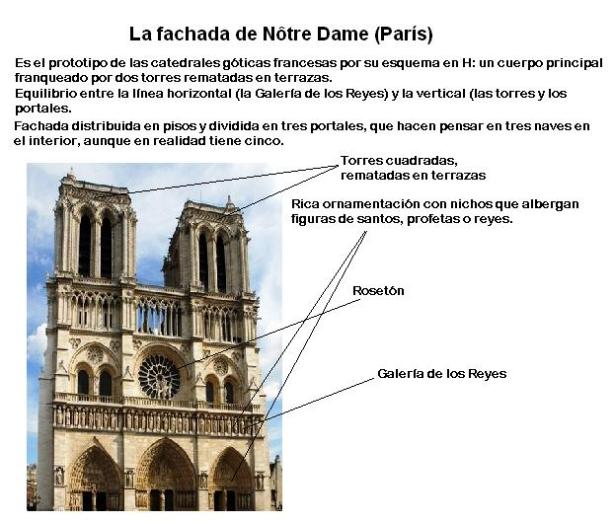

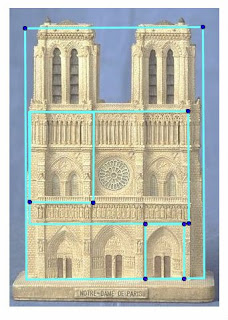

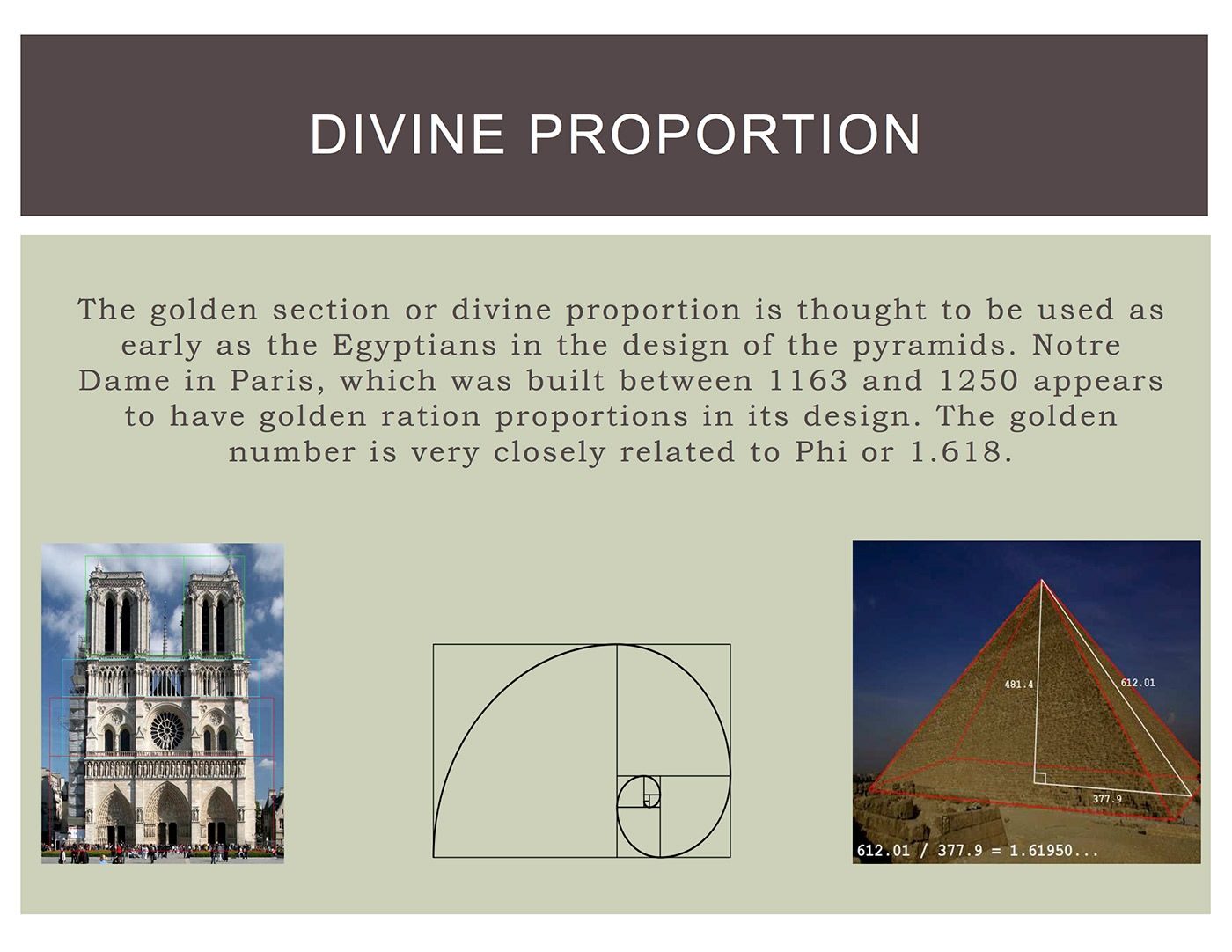

Built on the Ile de la Cite, Notre Dame was built on the site of two earlier churches. The foundation stone was laid by Pope Alexander III in 1163. The stone building demonstrates various styles of architecture, due to the fact that construction occurred for over 300 years. It is predominantly French Gothic, but also has elements of Renaissance and Naturalism. The cathedral interior is 427 feet x 157 feet in plan. The two Gothic towers on the west façade are 223 feet high. They were intended to be crowned by spires, but the spires were never built. The cathedral is especially loved for its three stained glass rose windows and daring flying buttresses. During the Revolution, the building was extensively damaged and was saved from demolition by the emperor Napoleon.

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris

Taj Mahal

Built in Agra between 1631 and 1648, the Taj Mahal is a white marble mausoleum designed by Ustad-Ahmad Lahori. This jewel of Indian architecture was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his favorite wife. Additional buildings and elements were completed in 1653. The square tomb is raised and is dramatically located at the end of a formal garden. On the interior, the tomb chamber is octagonal and is surrounded by hallways and four corner rooms. Building materials are brick and lime veneered with marble and sandstone.

Taj Mahal designed by Ustad-Ahmad Lahori

As you can see from the above examples, the application of mathematical principles can result in some pretty amazing architecture. The architects’ work reflects eye-catching harmony and balance. Although these buildings are all quite old, their designs have pleasing proportions which have truly passed the test of time.

https://bleckarchitects.com/math-in-architecture/

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

LLAVE DE ORO Y DE PLATA AL IGUAL QUE LA MANZANA

Incendio Notre Dame: Última hora de la catedral de París (15 DE ABRIL)

Incendio Notre Dame (París), en directo (Bertrand Guay / AFP)

PHI A NOTRE-DAME

A la catredal de Notre Dame hi observem més rectanlges auris: Creat per Mario Pastor

The DaVinci Code, Notre Dame Cathedral from DaVinci Code

original movie prop

August 23, 2018/

The Golden Section (aka Golden Mean, and Golden Ratio) phys.org

We use math in architecture on a daily basis to solve problems. We use it to achieve both functional and aesthetic advantages. By applying math to our architectural designs through the use of the Golden Section and other mathematical principles, we can achieve harmony and balance. As you will see from some of the examples below, the application of mathematical principles can result in beautiful and long-lasting architecture which has passed the test of time.

Using Math in Architecture for Function and Form

We use math in architecture every day at our office. For example, we use math to calculate the area of a building site or office space. Math helps us to determine the volume of gravel or soil that is needed to fill a hole. We rely on math when designing safe building structures and bridges by calculating loads and spans. Math also helps us to determine the best material to use for a structure, such as wood, concrete, or steel.

“Without mathematics there is no art.” – Luca Pacioli, De divina proportione, 1509

Architects also use math when making aesthetic decisions. For instance, we use numbers to achieve attractive proportion and harmony. This may seem counter-intuitive, but architects routinely apply a combination of math, science, and art to create attractive and functional structures. One example of this is when we use math to achieve harmony and proportion by applying a well-known principle called the Golden Section

Math and Proportion – The Golden Section

Perfect proportions of the human body – The Vitruvian Man – by Leonardo da Vinci.

We tend to think of beauty as purely subjective, but that is not necessarily the case. There is a relationship between math and beauty. By applying math to our architectural designs through the use of the Golden Section and other mathematical principles, we can achieve harmony and balance.

The Golden Section is one example of a mathematical principle that is believed to result in pleasing proportions. It was mentioned in the works of the Greek mathematician Euclid, the father of geometry. Since the 4th century, artists and architects have applied the Golden Section to their work.

The Golden Section is a rectangular form that, when cut in half or doubled, results in the same proportion as the original form. The proportions are 1: the square root of 2 (1.414) It is one of many mathematical principles that architects use to bring beautiful proportion to their designs.

Examples of the Golden Section are found extensively in nature, including the human body. The influential author Vitruvius asserted that the best designs are based on the perfect proportions of the human body.

Over the years many well-known artists and architects, such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, used the Golden Section to define the dimensions and proportions in their works. For example, you can see the Golden Section demonstrated in DaVinci’s painting Mona Lisa and his drawing Vitruvian Man.

Famous Buildings Influenced by Mathematical Principles

Here are some examples of famous buildings universally recognized for their beauty. We believe their architects used math and the principals of the Golden Section in their design:

Parthenon

The classical Doric columned Parthenon was built on the Acropolis between 447 and 432 BC. It was designed by the architects Iktinos and Kallikrates. The temple had two rooms to shelter a gold and ivory statue of the goddess Athena and her treasure. Visitors to the Parthenon viewed the statue and temple from the outside. The refined exterior is recognized for its proportional harmony which has influenced generations of designers. The pediment and frieze were decorated with sculpted scenes of Athena, the Gods, and heroes.

Parthenon Golden Section

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris

Built on the Ile de la Cite, Notre Dame was built on the site of two earlier churches. The foundation stone was laid by Pope Alexander III in 1163. The stone building demonstrates various styles of architecture, due to the fact that construction occurred for over 300 years. It is predominantly French Gothic, but also has elements of Renaissance and Naturalism. The cathedral interior is 427 feet x 157 feet in plan. The two Gothic towers on the west façade are 223 feet high. They were intended to be crowned by spires, but the spires were never built. The cathedral is especially loved for its three stained glass rose windows and daring flying buttresses. During the Revolution, the building was extensively damaged and was saved from demolition by the emperor Napoleon.

Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris

Taj Mahal

Built in Agra between 1631 and 1648, the Taj Mahal is a white marble mausoleum designed by Ustad-Ahmad Lahori. This jewel of Indian architecture was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his favorite wife. Additional buildings and elements were completed in 1653. The square tomb is raised and is dramatically located at the end of a formal garden. On the interior, the tomb chamber is octagonal and is surrounded by hallways and four corner rooms. Building materials are brick and lime veneered with marble and sandstone.

Taj Mahal designed by Ustad-Ahmad Lahori

As you can see from the above examples, the application of mathematical principles can result in some pretty amazing architecture. The architects’ work reflects eye-catching harmony and balance. Although these buildings are all quite old, their designs have pleasing proportions which have truly passed the test of time.

https://bleckarchitects.com/math-in-architecture/

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eye within an interlocking circle and triangle

The 18th century church of Santa Maria della Maddalena (1763-90), better known simply as La Maddalena, was designed by the Venetian architect Tommaso Temanza (1705-89).

The entrance to the church is surmounted by the inscription SAPIENTIA AEDIFICAVIT SIBI DOMUM (Wisdom has built herself a home) and a curious image of an eye surrounded by an interlocking circle and triangle.

The all-seeing eye is one of the symbols of freemasonry and both the architect and the patron (a member of the Baffo family) of the church were freemasons.

Temanza's ashes are interred in La Maddalena.

La Maddalena

La Maddalena

Tomb of Tommaso Temanza https://www.picturesfromitaly.com/venice/freemasonry-and-the-church-of-santa-maria-della-maddalena-venice

the Apple

|

|

|

|

|

LA SANGRE DEL CORDERO EN EL DINTEL, EN CONTEXTO AL EXODO PASCUAL, ES UN TIPO DEL GRIAL

1. Éxodo 12:7: Y tomarán de la sangre, y la pondrán en los dos postes y en el DINTEL de las casas en que lo han de comer.

2. Éxodo 12:22: Y tomad un manojo de hisopo, y mojadlo en la sangre que estará en un lebrillo, y untad el DINTEL y los dos postes con la sangre que estará en el lebrillo; y ninguno de vosotros salga de las puertas de su casa hasta la mañana.

3. Éxodo 12:23: Porque Jehová pasará hiriendo a los egipcios; y cuando vea la sangre en el DINTEL y en los dos postes, pasará Jehová aquella puerta, y no dejará entrar al heridor en vuestras casas para herir.

Dintel

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Esquema de estructura adintelada.

Un dintel es un elemento estructural horizontal que salva un espacio libre entre dos apoyos. Es el elemento superior que permite abrir huecos en los muros para conformar puertas, ventanas o pórticos. Por extensión, el tipo de arquitectura, o construcción, que utiliza el uso de dinteles para cubrir los espacios en los edificios se llama arquitectura adintelada, o construcción adintelada. La que utiliza arcos o bóvedas se denomina arquitectura abovedada.

Los mejores exponentes de arquitectura adintelada en piedra son los edificios monumentales del Antiguo Egipto y la Grecia clásica. La palabra dintel proviene de la palabra latina: limitellus, que deriva etimológicamente de limen y limes. En latín la palabra limen significa umbral, puerta, entrada o comienzo, y limes se refiere a un sendero entre dos campos, límite o muralla.

[editar] Resistencia

Para un dintel cuyos extremos recaigan sobre los elementos verticales cuyo espacio libre salva el dintel, las mayores tensiones se da sobre la sección transversal central. En este caso, la tensión sobre el dintel, si éste es de canto pequeño en relación a la longitud, puede calcularse a partir de la teoría de vigas de Euler-Bernouilli para la flexión mecánica de vigas (si el canto es apreciable en relación a la longitud debe emplerarse la teoría de Timoschenko, que considera igualmente el efecto del esfuerzo cortante). En el caso anterior, la flexión hace que la parte superior del mismo esté comprimida, y la inferior esté traccionada.

Los materiales rígidos como las rocas (el hormigón y otros materiales de tipo cerámico) soportan peor los esfuerzos de tracción que los de compresión, por lo que la patología más habitual en los dinteles pétreos son las fisuras que surgen desde la parte inferior de la cara inferior y progresan hasta la parte superior.

|

|

|

|

|

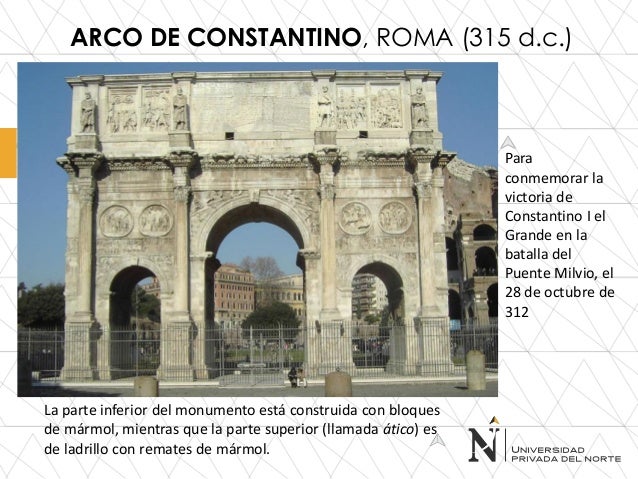

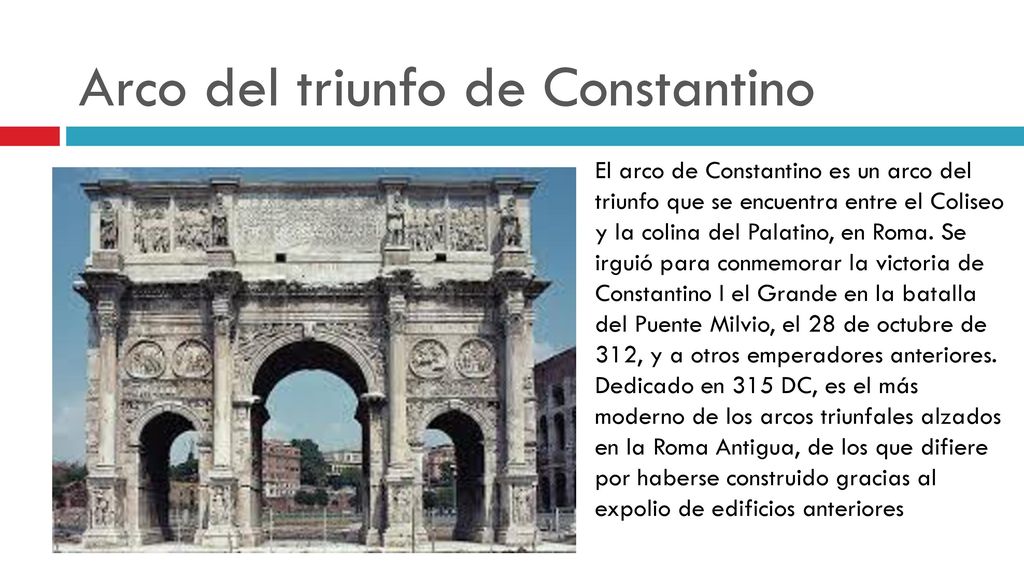

Arco de Constantino, triunfo del Emperador

Cuando se dicen las palabras «arco del triunfo» la mente de los turistas se va principalmente para el que se encuentra en París, pero hay algunas otras construcciones en el mundo que son estructuras similares. Uno de estos que es también reconocido es el Arco de Constantino, que está en la ciudad de Roma, capital de Italia, y que está entre el Coliseo y la Colina Palatina.

Este arco, que es el más moderno de los que se hicieron en la antigua Roma, fue construido como conmemoración de la victoria de Constantino I el Grande en la batalla del Puente Milvio que fue muy importante en la historia cristiana. Se dice que este emperador tuvo una visión de Cristo la noche antes de la batalla y a pesar de que su ejército era más pequeño, llevó el símbolo de la cruz en la batalla y triunfó, tras lo cual se convirtió a esta religión.

El Arco de Constantino fue hecho alrededor del año 315 y es el último que queda de su estilo en esta ciudad, teniendo 21 metros de alto, 26 de ancho y un poco más de siete de profundidad. Este arco es una copia del de Septimio Severo, que está en el Foro Romano de esta población, teniendo un ático que está hecho en ladrillos y cubierto por mármol y columnas en sus laterales.

En la parte que mira hacia el Coliseo se puede ver una banda con esculturas que muestra la batalla del Puente Milvio y a cada uno de sus lados tiene cuatro columnas de estilo Corintio que se encargan de decorar el arco. En las partes altas de esta columna se pueden ver relieves que muestran a bárbaros capturados que tienen a sus lados a soldados romanos.

También es común ver en otros relieves de figuras en posición de victoria o con trofeos, así como escenas de caza y de sacrificios, así como varias de las batallas que ganó el Emperador Constantino I durante su gobierno. Dentro del arco principal, y los dos pequeños, se pueden ver también algunos bustos, pero que están en tan mal estado que no es posible reconocer a las personas que representan.

|

|

|

|

|

![Stargate Special Edition [Reino Unido] [DVD]: Amazon.es: Kurt Russell: Películas y TV](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Gr2lgt03L.jpg)

LA SANGRE DEL CORDERO EN EL DINTEL, EN CONTEXTO AL EXODO PASCUAL, ES UN TIPO DEL GRIAL

1. Éxodo 12:7: Y tomarán de la sangre, y la pondrán en los dos postes y en el DINTEL de las casas en que lo han de comer.

2. Éxodo 12:22: Y tomad un manojo de hisopo, y mojadlo en la sangre que estará en un lebrillo, y untad el DINTEL y los dos postes con la sangre que estará en el lebrillo; y ninguno de vosotros salga de las puertas de su casa hasta la mañana.

3. Éxodo 12:23: Porque Jehová pasará hiriendo a los egipcios; y cuando vea la sangre en el DINTEL y en los dos postes, pasará Jehová aquella puerta, y no dejará entrar al heridor en vuestras casas para herir.

Dintel

De Wikipedia, la enciclopedia libre

Esquema de estructura adintelada.

Un dintel es un elemento estructural horizontal que salva un espacio libre entre dos apoyos. Es el elemento superior que permite abrir huecos en los muros para conformar puertas, ventanas o pórticos. Por extensión, el tipo de arquitectura, o construcción, que utiliza el uso de dinteles para cubrir los espacios en los edificios se llama arquitectura adintelada, o construcción adintelada. La que utiliza arcos o bóvedas se denomina arquitectura abovedada.

Los mejores exponentes de arquitectura adintelada en piedra son los edificios monumentales del Antiguo Egipto y la Grecia clásica. La palabra dintel proviene de la palabra latina: limitellus, que deriva etimológicamente de limen y limes. En latín la palabra limen significa umbral, puerta, entrada o comienzo, y limes se refiere a un sendero entre dos campos, límite o muralla.

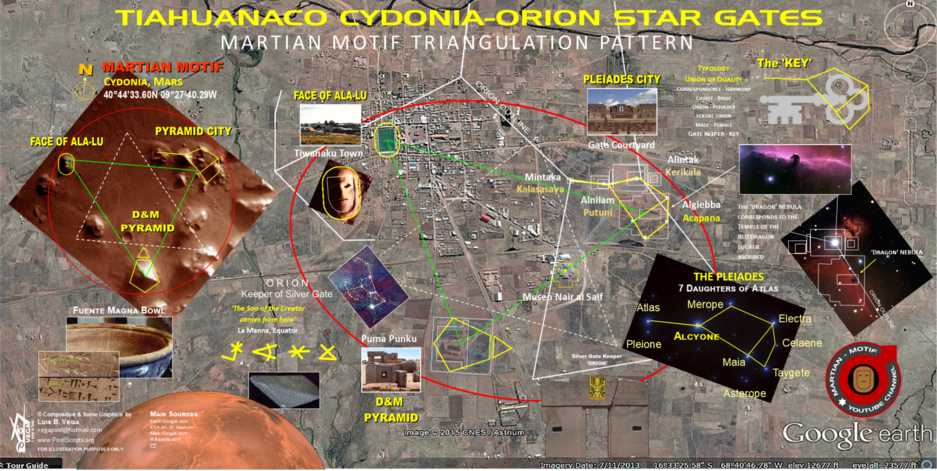

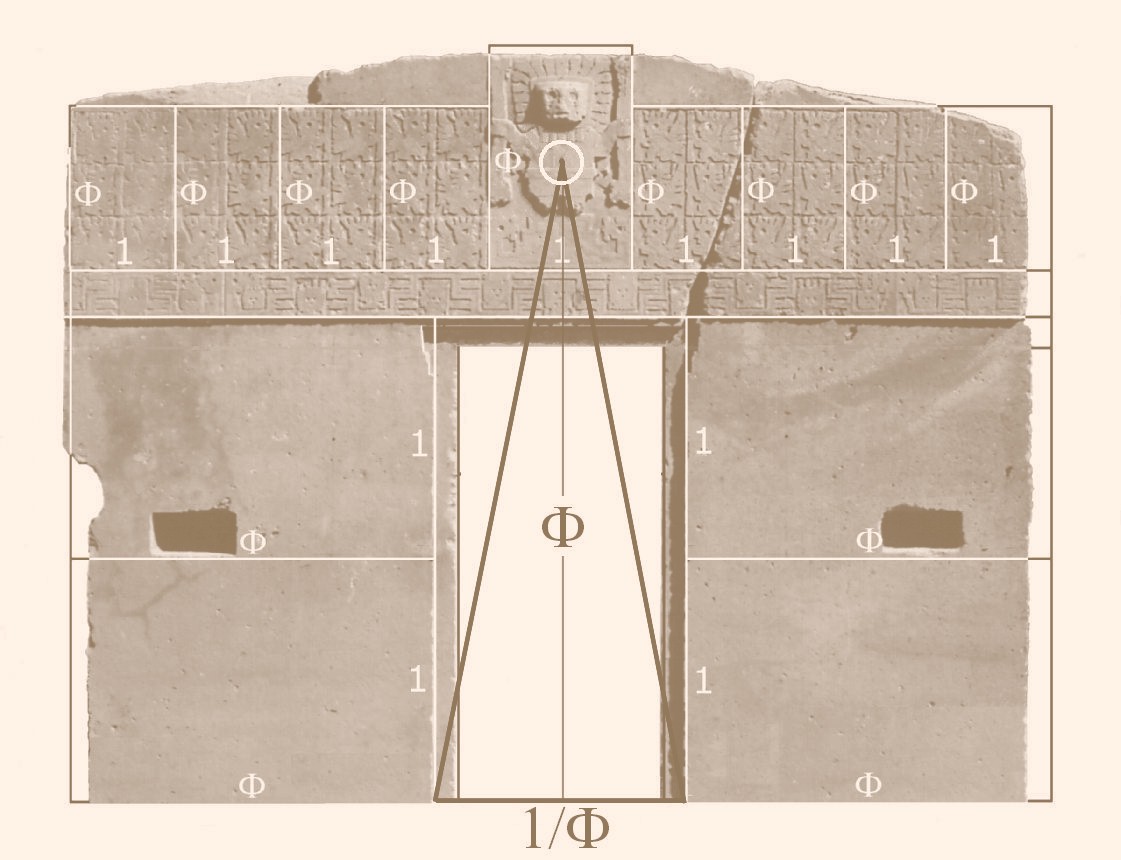

Comparen las dos figuras anteriores y noten que la LUZ SOLAR PENETRA, en este caso EN LA PUERTA DE TIWANAKU (BOLIVIA) en los equinoccios, osea el 20/21 de marzo y los 21/22 de septiembre. CONCRETAMENTE LA FIESTA DE LOS TABERNACULOS ES PRIMA HERMANA DE LA FIESTA PASCUAL. EN ESTE MARCO, INSISTO, EL SOL, SI USTED COMPARA CON LA FIGURA SUPERIOR, EN LOS MISMOS EQUINOCCIOS LA LUZ SOLAR CHOCA CON LA PIRAMIDE VATICANA E INCLUSO INGRESA O PENETRA ADENTRO DEL TEMPLO DE SAN PEDRO. PREGUNTO: ¿SI LA PLAZA DE MARIA DE LA VICTORIA ESTA UBICADA EN LA MISMA LINEA EQUINOCCIAL, QUIEN ES EN ESTE MARCO LA MISMA, EN EL CONTEXTO QUE LA PASCUA TAMBIEN TIENE ESA REFERENCIA? CUALQUIER PERSONA QUE TIENE TRES DEDOS DE FRENTE SE DA CUENTA QUE ES MARIA LA MAGDALENA. SI NO ES ASI PREGUNTO:

¿PORQUE CRISTO SE PRESENTO SIENDO VENCEDOR EL 17 DE NISSAN, OSEA EN EL EQUINOCCIO FRENTE A MARIA MAGDALENA?

CONCLUYO:

MARIA LA VICTORIA ES MARIA MAGDALENA

|

|

|

|

|

Granger - Historical Picture Archive

Image of SAINT MARK'S: NOAH'S ARK. - Mosaic From The Pala D'Oro Or Golden Altar, At Saint Mark's Basilica In Venice, Italy,

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

37 a 51 de 81

Siguiente Anterior

37 a 51 de 81

Siguiente Último

Último

|

Incendio Notre Dame (París), en directo (Bertrand Guay / AFP)

Incendio Notre Dame (París), en directo (Bertrand Guay / AFP)

![Stargate Special Edition [Reino Unido] [DVD]: Amazon.es: Kurt Russell: Películas y TV](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/I/51Gr2lgt03L.jpg)