|

|

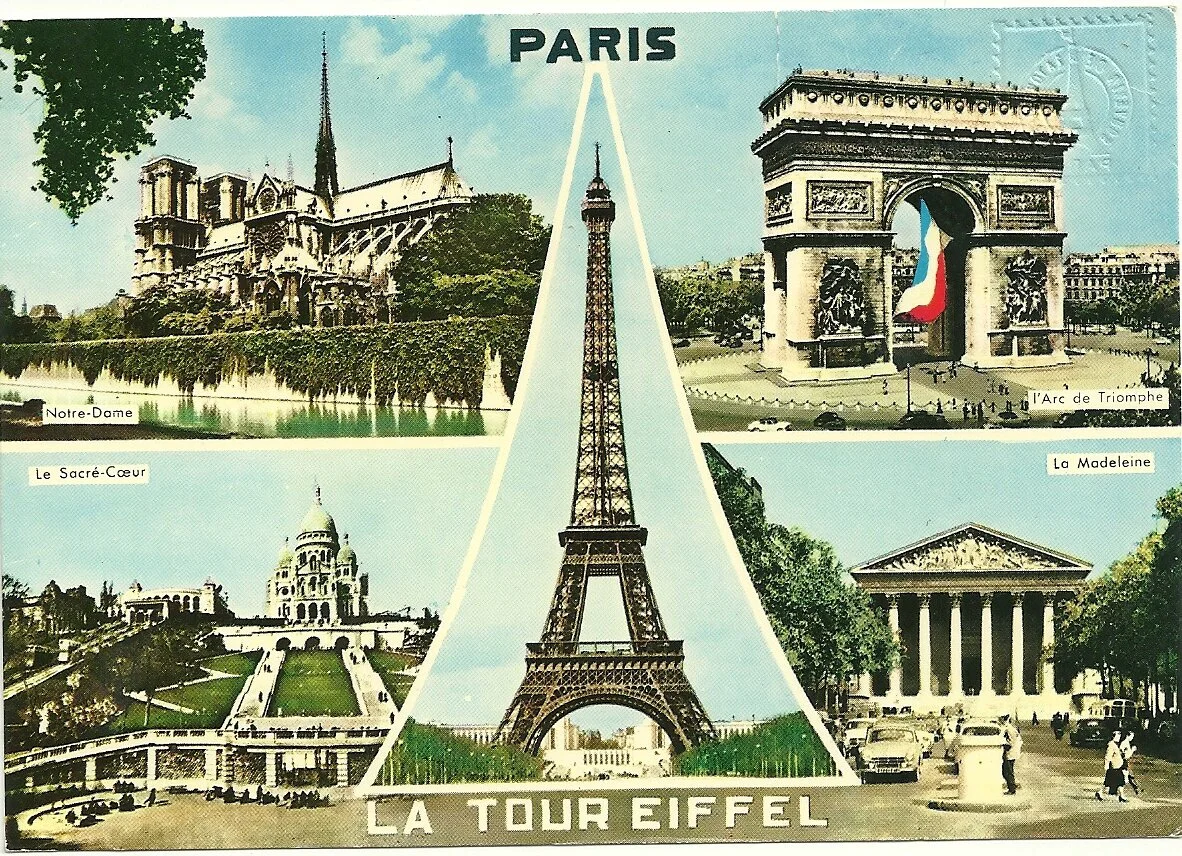

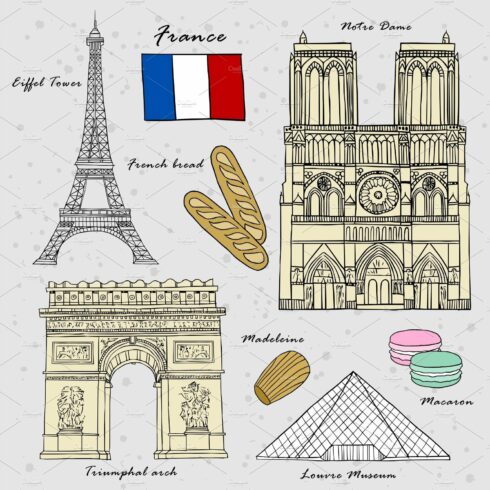

26 Historic Buildings to Visit the Next Time You’re in Paris

© Corbis

Paris is known today as the City of Lights. Thousands of years ago it was called Midwater-Dwelling—which is how its Latin name, Lutetia, can be translated. This list covers just a few of the most notable structures built in Paris over all of these years.

Earlier versions of the descriptions of these buildings first appeared in 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die, edited by Mark Irving (2016). Writers’ names appear in parentheses.

-

Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris has been the cathedral of the city of Paris since the Middle Ages. It is a Gothic exemplar of a radical change in the Romanesque tradition of construction, both in terms of naturalistic decoration and revolutionary engineering techniques. In particular, via a framework of flying buttresses, external arched struts receive the lateral thrust of high vaults and provide sufficient strength and rigidity to allow the use of relatively slender supports in the main arcade. The cathedral stands on the Île de la Cité, an island in the middle of the River Seine, on a site previously occupied by Paris’s first Christian church, the Basilica of Saint-Étienne, as well as an earlier Gallo-Roman temple to Jupiter, and the original Notre-Dame, built by Childebert I, the king of the Franks, in 528. Maurice de Sully, the bishop of Paris, began construction in 1163 during the reign of King Louis VII, and building continued until 1330. The spire was erected in the 1800s during a renovation by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, though it was destroyed by fire in 2019.

The western facade is the distinguishing feature of the cathedral. It comprises the Gallery of Kings, a horizontal row of stone sculptures; a rose window glorifying the Virgin, who also appears in statue form below; the Gallery of Chimeras; two unfinished square towers; and three portals, those of the Virgin, the Last Judgment, and St. Anne, with richly carved sculptures around the ornate doorways. The circular rose window in the west front and two more in the north and south transept crossings, created between 1250 and 1270, are masterpieces of Gothic engineering. The stained glass is supported by delicate radiating webs of carved stone tracery. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Hôtel de Soubise

The Hôtel de Soubise is a city mansion built for the prince and princess de Soubise. In 1700 François de Rohan bought the Hôtel de Clisson, and in 1704 the architect Pierre-Alexis Delamair (1675–1745) was hired to renovate and remodel the building. Delamair designed the huge courtyard on the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois. On the far side of the courtyard is a facade with twin colonnades topped by a series of statues by Robert Le Lorrain representing the four seasons.

In 1708 Delamair was replaced by Germain Boffrand (1667–1754), who carried out all the interior decoration for the apartments for the prince’s son, Hercule-Mériadec de Rohan-Soubise, on the ground floor and for the princess on the piano nobile (principal floor), both of which featured oval salons looking into the garden.

The interiors are considered among the finest Rococo decorative interiors in France. In the prince’s salon, the wood paneling is painted a pale green and surmounted by plaster reliefs. The princess’s salon is painted white with delicate gilded moldings and features arched niches containing mirrors, windows, and panels. Above the panels are shallow arches containing cherubs and eight paintings by Charles Natoire depicting the history of Psyche. Plaster rocailles (shellwork) and a decorative band of medallions and shields complete the sweetly disordered effect. At the time of the French Revolution, the building was given to the National Archives. A Napoleonic decree of 1808 granted the residence to the state. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Panthéon

The Panthéon is the quintessential Neoclassical monument in Paris and an outstanding example of Enlightenment architecture. Commissioned as the church of St. Geneviève by King Louis XV, the project has become known as a secular building and a prestigious tomb dedicated to great French political and artistic figures including Mirabeau, Voltaire, Rousseau, Hugo, Zola, Curie, and Malraux, who have been honored and interred in the vaults following the ceremony of Panthéonization.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713–80) was a self-taught architect and tutor to the marquis de Marigny, general director of the king’s buildings, who had been influenced by the Pantheon in Rome. Soufflot claimed that his principal aim was to unite “the structural lightness of Gothic churches with the purity and magnificence of Greek architecture.” His Panthéon was revolutionary: built on the Greek cross plan of a central dome and four equal transepts, his innovation in construction was to use rational scientific and mathematical principles to determine structural formulas for the engineering of the building. This eliminated many of the supporting piers and walls with the result that the vaulting and interiors are slender and elegant. The Neoclassical interior contrasts with the solidity and austere geometry of the exterior. The initial scheme was considered too lacking in gravity and was replaced with a more funereal scheme, which involved blocking 40 windows and destroying the original sculptural decorations. The Panthéon was the location for Léon Foucault’s pendulum experiment to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth in 1851. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Arc de Triomphe

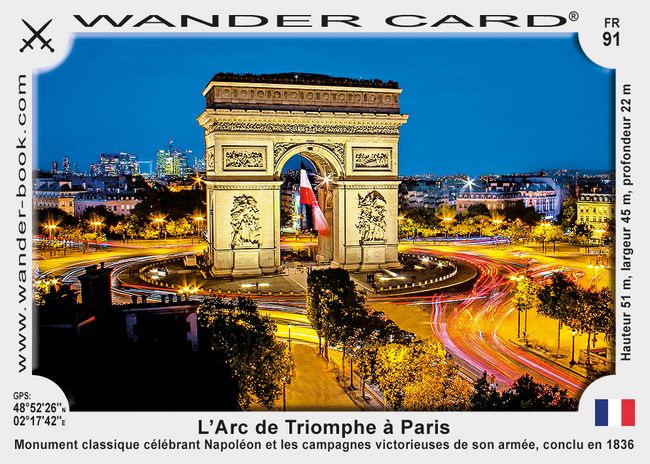

Arc de TriompheNighttime view of the Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

© Corbis

The Arc de Triomphe is one of the world’s largest triumphal arches. Inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome, it was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1806 after his victory at Austerlitz, to commemorate all the victories of the French army; it has since engendered a worldwide military taste for triumphal and nationalistic monuments.

The astylar design consists of a simple arch with a vaulted passageway topped by an attic. The monument’s iconography includes four main allegorical sculptural reliefs on the four pillars of the Arc. The Triumph of Napoleon, 1810, by Jean-Pierre Cortot, shows an imperial Napoleon, wearing a laurel wreath and toga, accepting the surrender of a city while Fame blows a trumpet. There are two reliefs by Antoine Etex: Resistance, depicting an equestrian figure and a naked soldier defending his family, protected by the spirit of the future, and Peace, in which a warrior protected by Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, is sheathing his sword surrounded by scenes of agricultural laborers. The Departure of the Volunteers of ’92, commonly called La Marseillaise, by François Rude, presents naked and patriotic figures, led by Bellona, goddess of war, against the enemies of France. In the vault of the Arc de Triomphe are engraved the names of 128 battles of the Republican and Napoleonic regimes. The attic is decorated with 30 shields, each inscribed with a military victory, and the inner walls list the names of 558 French generals, with those who died in battle underlined.

The arch has subsequently become a symbol of national unity and reconciliation as the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I. He was interred here on Armistice Day, 1920; today there is an eternal flame commemorating the dead of two world wars. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

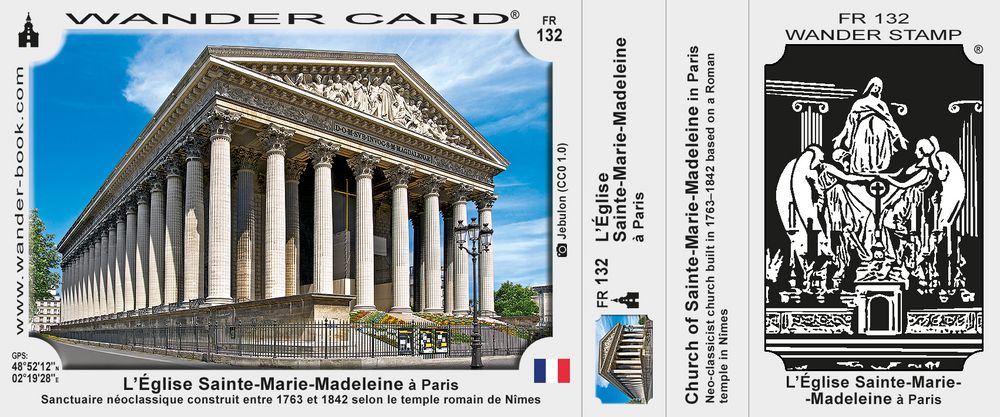

Church of St. Mary Magdalene

In 1806 Napoleon commissioned Pierre-Alexandre Vignon, inspector–general of buildings of the Republic, to build a Temple to the Glory of the Great Army and provide a monumental view to the north of Place de la Concorde. Known as ”The Madeleine,” this church was designed as a Neoclassical temple surrounded by a Corinthian colonnade, reflecting the predominant taste for Classical art and architecture. The proposal of the Arc de Triomphe, however, reduced the original commemorative intention for the temple, and, after the fall of Napoleon, King Louis XVIII ordered that the church be consecrated to St. Mary Magdalene in Paris in 1842.

The Madeleine has no steps at the sides but a grand entrance of 28 steps at each end. The church’s exterior is surrounded by 52 Corinthian columns, 66 feet (20 meters) high. The pediment sculpture of Mary Magdalene at the Last Judgment is by Philippe-Henri Lemaire; bronze relief designs in the church doors represent the Ten Commandments.

The 19th-century interior is lavishly gilded. Above the altar is a statue of the ascension of St. Mary Magdalene by Charles Marochetti and a fresco by Jules-Claude Ziegler, The History of Christianity, with Napoleon as the central figure surrounded by such luminaries as Michelangelo, Constantine, and Joan of Arc. (Jeremy Hunt)

https://www.britannica.com/list/26-historic-buildings-to-visit-the-next-time-youre-in-paris |

|

|

|

|

D-DAY 1944 AND A FULL MOON.

D-Day June 6, 1944 was very carefully timed to coincide with the moment of June’s Full Moon. It was reaching the highest point in the sky at 1:19 a.m. and just as the American airborne operations began. There was a Full Moon shining all night long in Normandy.

Why D-Day required a Full Moon.

As well as moonlight throughout the night, the tides were crucial, and that’s where a Full Moon really comes in. The Allies were able to use a low tide at 5:23 a.m. on D-Day to destroy the Germans’ underwater defenses at Omaha Beach.

But they also wanted rising water so that they could beach a craft and not get stranded.

If you want to have an insight into the conditions of the Normandy landings, 76 years ago, you could visit the invasion beaches of Normandy, France on June 5 and 6, when June’s Full Moon will shine all night long.

For those not able to be at the Normandy Beaches, you could experience an eerie feeling tonight, June 6, 2020 on our own beaches, when JUNE’s FULL MOON will SHINE ALL NIGHT LONG…….. REMEMBER D-DAY.

|

|

|

|

|

Primer Primer  Anterior 2 a 3 de 3 Siguiente Anterior 2 a 3 de 3 Siguiente  Último Último  |

|

|

|

|

|

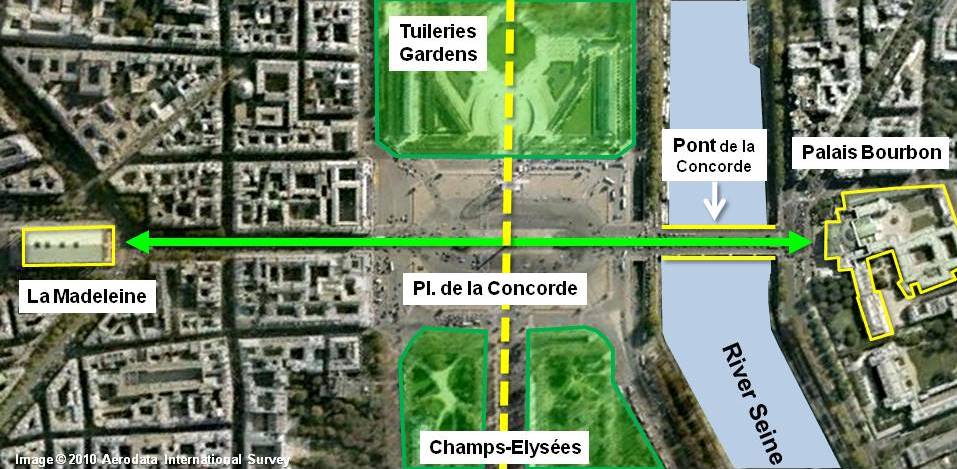

Earth from Space – Arc de Triomphe, Paris

Status Report

May 13, 2022

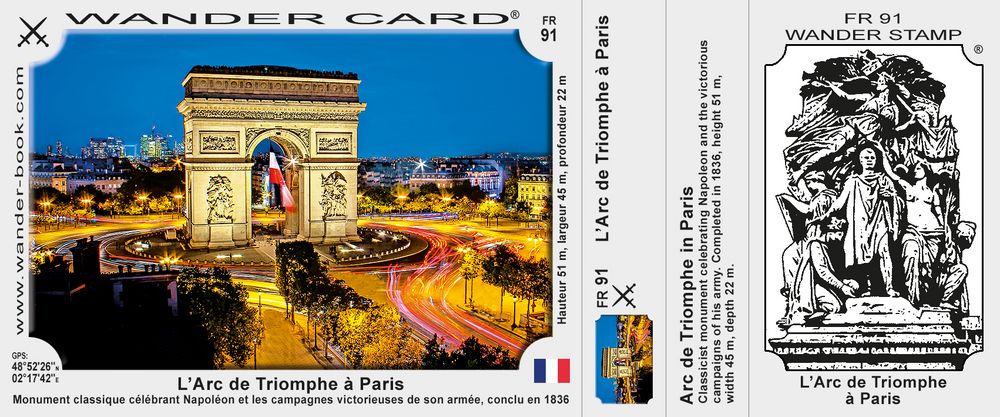

Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

ESA

This striking, high-resolution image of the Arc de Triomphe, in Paris, was captured by Planet SkySat – a fleet of satellites that have just joined ESA’s Third Party Mission Programme in April 2022.

The Arc de Triomphe, or in full Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, is an iconic symbol of France and one of the world’s best-known commemorative monuments. The triumphal arch was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1806 to celebrate the military achievements of the French armies. Construction of the arch began the following year, on 15 August (Napoleon’s birthday).

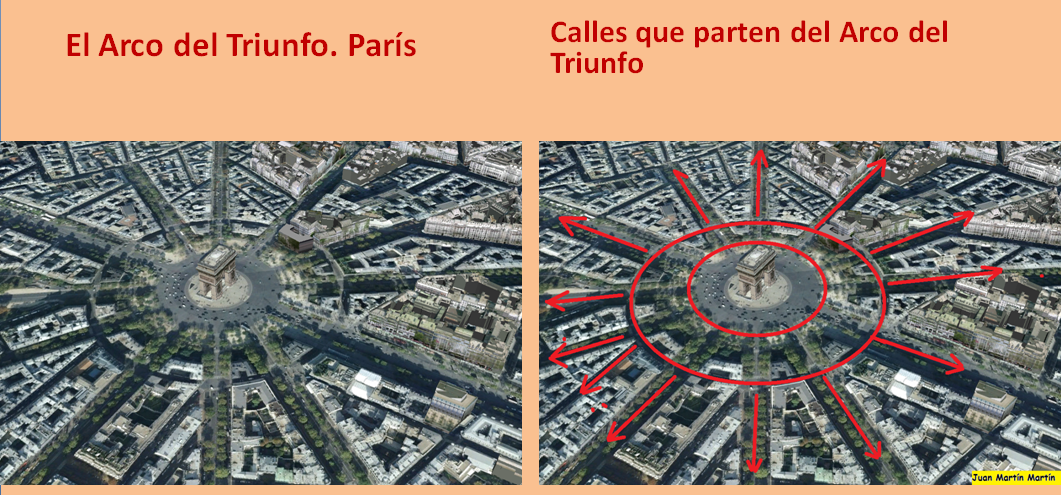

The arch stands at the centre of the Place Charles de Gaulle, the meeting point of 12 grand avenues which form a star (or étoile), which is why it is also referred to as the Arch of Triumph of the Star. The arch is 50 m high and 45 m wide.

The names of all French victories and generals are inscribed on the arch’s inner and outer surfaces, while the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I lies beneath its vault. The tomb’s flame is rekindled every evening as a symbol of the enduring nature of the commemoration and respect shown to those who have fallen in the name of France.

The Arc de Triomphe’s location at the Place Charles de Gaulle places it at the heart of the capital and the western terminus of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées (visible in the bottom-right of the image). Often referred to as the ‘most beautiful avenue in the world’, the Champs-Élysées is known for its theatres, cafés and luxury shops, as the finish of the Tour de France cycling race, as well as for its annual Bastille Day military parade.

This image, captured on 9 April 2022, was provided by Planet SkySat – a fleet of 21 very high-resolution satellites capable of collecting images multiple times during the day. SkySat’s satellite imagery, with 50 cm spatial resolution, is high enough to focus on areas of great interest, identifying objects such as vehicles and shipping containers.

SkySat data, along with PlanetScope (both owned and operated by Planet Labs), serve numerous commercial and governmental applications. These data are now available through ESA’s Third Party Mission programme – enabling researchers, scientists and companies from around the world the ability to access Planet’s high-frequency, high-resolution satellite data for non-commercial use.

Within this programme, Planet joins more than 50 other missions to add near-daily PlanetScope imagery, 50 cm SkySat imagery, and RapidEye archive data to this global network.

Peggy Fischer, Mission Manager for ESA’s Third Party Missions, commented, “We are very pleased to welcome PlanetScope and SkySat to ESA’s Third Party Missions portfolio and to begin the distribution of the Planet data through the ESA Earthnet Programme.

“The high-resolution and high-frequency imagery from these satellite constellations will provide an invaluable resource for the European R&D and applications community, greatly benefiting research and business opportunities across a wide range of sectors.”

To find out more on how to apply to the Earthnet Programme and get started with Planet data, click here.

– Download the full high-resolution image.

|

|

|

|

|

How Napoleon's Arc de Triomphe Became a Symbol of Paris

The Arc de Triomphe shines during the Christmas season on the Champs-Elysées in Paris, France. EDWARD BERTHELOT/GETTY IMAGESAs far as iconic Paris landmarks go, it's a toss-up between the Eiffel Tower and the Arc de Triomphe. If the Eiffel Tower boasts more T-shirts and wall art bearing its image, the Arc de Triomphe has given us some great film scenes with cars circling (and circling) it. That's because it's located within a circular plaza where 12 avenues, including the Champs-Elysées, meet.

Originally called Place de l'Étoile (Square of the Star) because of its starlike formation, the plaza was renamed Place de Charles de Gaulle in 1970 after the 20th century French president. But it was a different leader we have to thank for the Arc de Triomphe, and he is just as much a symbol of France as the structure he commissioned.

Why the Arc de Triomphe Was Built

The triumphal arch was commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte to commemorate his victory at the Battle of Austerlitz and to "glorify the Grand Army" in general, according to Napoleon.org. Construction started in 1806, with the first stone laid on Aug. 15.

The arch, which Napoleon planned to ride through at the head of his victorious army, was inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome. But the French version would be much more impressive at 164 feet (50 meters) high and 148 feet (45 meters) wide compared to that of Titus, which is just 50 feet (15 meters) high and 44 feet (13 meters) wide.

"Napoleon was known for never doing things on the cheap and thinking big," says W. Jude LeBlanc, associate professor at the school of architecture at Georgia Institute of Technology in Atlanta.

The emperor called on architect Jean-François-Thérèse Chalgrin, who had spent some years in Rome and had previously worked on a project for Versailles and churches like Saint-Philippe-du-Roule and the Church of Saint-Sulpice.

This is a lantern slide of the Champs-Elysées in 1856 with the Arc de Triomphe on the horizon.

THE ROYAL PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY COLLECTION/V & A MUSEUM, LONDON/GETTY IMAGES

How Long It Took to Build the Arc de Triomphe

Perhaps Napoleon and Chalgrin were too ambitious in their proportions because the Neoclassical arch took 30 years to complete, although work was not continuous. In fact, it took more than two years just to lay the foundation.

It wasn't finished when Napoleon married his second wife, Marie-Louise de Habsburg-Lorraine, in 1810. As a substitute, he had a full-size replica crafted from wood, so he and his 19-year-old bride could pass under it.

Ironically, neither Napoleon nor Chalgrin saw the structure reach completion. Chalgrin died in 1811, and his former pupil Louis-Robert Goust took over the project. But in 1814, Napoleon abdicated, and work on the structure slowed to a crawl if it took place at all.

The monarchy was reinstated, and King Louis XVIII resumed work on the Arc de Triomphe in 1823, with the project finally being inaugurated in 1836 by King Louis-Philippe.

Although Napoleon didn't get see his completed triumphal arch, he did pass through it. When his body was returned to France in 1840 (he died on the island of Saint Helena in 1821), it was brought to les Invalides and passed under the Arc de Triomphe on the way there.

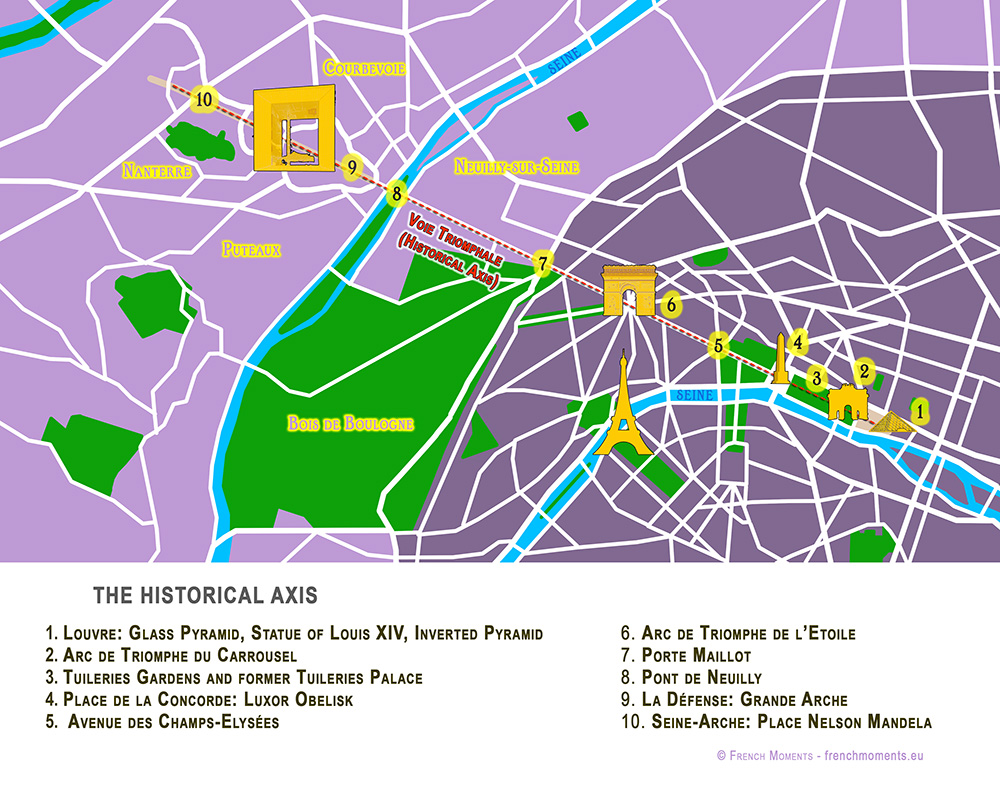

The Arc's Parisian Placement

The Arc de Triomphe and Place de Charles de Gaulle sit along the Axe Historique (Historical Axis) of Paris, which extends from the Louvre Museum to La Défense. The triumphal arch isn't the only one along the axis. At one end, the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, which was modeled on the Roman arches of Septimius and Constantine, sits between the Louvre and the Tuileries Garden. That one is about a third of the size and was also commissioned by Napoleon.

At the far end of the axis, La Grand Arche was built "as a strong unifying symbol for the bicentenary of the French Revolution" in 1989 and was a project French President François Mitterand. It was designed by Johan Otto V. Spreckelsen and is more than double the size of the Arc de Triomphe.

An aerial view of the Arc de Triomphe, which stands in the center of the Place de Charles de Gaulle, where 12 avenues, including the Champs-Elysées, meet.

ROGER VIOLLET GETTY IMAGES

With all these arches in Paris and around the world, what makes the Arc de Triomphe special?

"I don't know that it was structurally novel," says LeBlanc. Arches were well known at the time it was made, although Napoleon's was particularly massive. "What was unique was that it didn't have pilasters and columns."

The Arc includes many notable sculptures, with work by artists François Rude, Jean-Pierre Cortot and Antoine Etex on the pillars. Other surfaces include additional reliefs and the names of generals and battles.

Beneath the Arc de Triomphe are the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, added in 1921, and the eternal flame, which is rekindled each evening. Due to its scale, the Arc de Triomphe is known for offering one of the best views of the city from the observation deck at the top.

https://science.howstuffworks.com/engineering/architecture/arc-de-triomphe.htm |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

91 a 105 de 105

Siguiente Anterior

91 a 105 de 105

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

The Arc de Triomphe shines during the Christmas season on the Champs-Elysées in Paris, France. EDWARD BERTHELOT/GETTY IMAGES

The Arc de Triomphe shines during the Christmas season on the Champs-Elysées in Paris, France. EDWARD BERTHELOT/GETTY IMAGES

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(299x0:301x2)/pepsi-perfect-600x450-1-0dcee4c1f37140c5875ca7654e80ae10.jpg)

This is a lantern slide of the Champs-Elysées in 1856 with the Arc de Triomphe on the horizon.

This is a lantern slide of the Champs-Elysées in 1856 with the Arc de Triomphe on the horizon.

An aerial view of the Arc de Triomphe, which stands in the center of the Place de Charles de Gaulle, where 12 avenues, including the Champs-Elysées, meet.

An aerial view of the Arc de Triomphe, which stands in the center of the Place de Charles de Gaulle, where 12 avenues, including the Champs-Elysées, meet.