English physicist and mathematician Isaac Newton produced works exploring chronology, and biblical interpretation (especially of the Apocalypse), and alchemy. Some of this could be considered occult. Newton's scientific work may have been of lesser personal importance to him, as he placed emphasis on rediscovering the wisdom of the ancients. Historical research on Newton's occult studies in relation to his science have also been used to challenge the disenchantment narrative within critical theory.[1]

In the Early Modern Period of Newton's lifetime, the educated embraced a world view different from that of later centuries. Distinctions between science, superstition, and pseudoscience were still being formulated, and a devoutly Christian biblical perspective permeated Western culture.

Alchemical research

[edit]

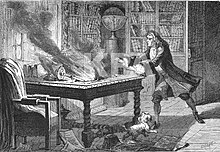

An 1874 engraving showing a probably apocryphal account of Newton's lab fire. In the story, Newton's dog, Diamond, started the fire, burning 20 years of research. Newton is thought to have said: "O Diamond, Diamond, thou little knowest the mischief thou hast done."[2]

An 1874 engraving showing a probably apocryphal account of Newton's lab fire. In the story, Newton's dog, Diamond, started the fire, burning 20 years of research. Newton is thought to have said: "O Diamond, Diamond, thou little knowest the mischief thou hast done."[2]

Much of what are known as Isaac Newton's occult studies can largely be attributed to his study of alchemy.[3] From a young age, Newton was deeply interested in all forms of natural sciences and materials science, an interest which would ultimately lead to some of his better-known contributions to science. His earliest encounters with certain alchemical theories and practices were when he was twelve years old, and boarding in the attic of an apothecary's shop.[4] During Newton's lifetime, the study of chemistry was still in its infancy, so many of his experimental studies used esoteric language and vague terminology more typically associated with alchemy and occultism.[5] It was not until several decades after Newton's death that experiments of stoichiometry under the pioneering works of Antoine Lavoisier were conducted, and analytical chemistry, with its associated nomenclature, came to resemble modern chemistry as we know it today. However, Newton's contemporary and fellow Royal Society member Robert Boyle had already discovered the basic concepts of modern chemistry and began establishing modern norms of experimental practice and communication in chemistry, information which Newton did not use.

Much of Newton's writing on alchemy may have been lost in a fire in his laboratory, so the true extent of his work in this area may have been larger than is currently known. Newton also suffered a nervous breakdown during his period of alchemical work.[6]

Newton's writings suggest that one of the main goals of his alchemy may have been the discovery of the philosopher's stone (a material believed to turn base metals into gold), and perhaps to a lesser extent, the discovery of the highly coveted Elixir of Life.[6] Newton reportedly believed that Diana's Tree, an alchemical demonstration producing a dendritic "growth" of silver from solution, was evidence that metals "possessed a sort of life."[7]

Some practices of alchemy were banned in England during Newton's lifetime, due in part to unscrupulous practitioners who would often promise wealthy benefactors unrealistic results in an attempt to swindle them. The English Crown, also fearing the potential devaluation of gold because of the creation of fake gold, made penalties for alchemy very severe. In some cases, the punishment for unsanctioned alchemy would include the public hanging of an offender on a gilded scaffold while adorned with tinsel and other items.[6]

Due to the threat of punishment and the potential scrutiny he feared from his peers within the scientific community, Newton may have deliberately left his work on alchemical subjects unpublished. Newton was well known as being highly sensitive to criticism, such as the numerous instances when he was criticized by Robert Hooke, and his admitted reluctance to publish any substantial information regarding calculus before 1693. A perfectionist by nature, Newton also refrained from publication of material that he felt was incomplete, as evident from a 38-year gap from Newton's conception of calculus in 1666 and its final full publication in 1704, which would ultimately lead to the infamous Leibniz–Newton calculus controversy.

Most of the scientist's manuscript heritage after his death passed to John Conduitt, the husband of his niece Catherine.[8] To evaluate the manuscripts, physician Thomas Pellet was involved, who decided that only "the Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms", an unreleased fragment of "Principia", "Observations upon the Prophesies of Daniel and the Apocalypse of St. John" and "Paradoxical Questions Concerning the Morals and Actions of Athanasius and His Followers" were suitable for publication. The remaining manuscripts, according to Pellet, were "foul draughts of the Prophetic stile" and were not suitable for publication. After the death of J. Conduitt in 1737, manuscripts were transferred to Catherine, who unsuccessfully tried to publish the theological notes of her uncle. She consulted with Newton's friend, the theologian Arthur Ashley Sykes (1684–1756). Sykes kept 11 manuscripts for himself, and the rest of the archive passed into the family of Catherine's daughter, who married the John Wallop, Viscount Lymington, and was then owned by the Earls of Portsmouth. After Sykes' death, his documents came to the Rev. Jeffery Ekins (d. 1791) and were kept in his family until they were presented to the New College, Oxford in 1872. Until the mid-19th century, few had access to the Portsmouth collection, including David Brewster, a renowned physicist and biographer of Newton. In 1872, the fifth Earl of Portsmouth transferred part of the manuscripts (mainly of a physical and mathematical nature) to Cambridge University.

In 1936, a collection of Isaac Newton's unpublished works were auctioned by Sotheby's on behalf of Gerard Wallop, 9th Earl of Portsmouth. Known as the "Portsmouth Papers", this material consisted of 329 lots of Newton's manuscripts, over a third of which were filled with content that appeared to be alchemical in nature. At the time of Newton's death this material was considered "unfit to publish" by Newton's estate, and consequently fell into obscurity until their somewhat sensational reemergence in 1936.[10]

At the auction, many of these documents, along with Newton's death mask, were purchased by economist John Maynard Keynes, who throughout his life collected many of Newton's alchemical writings.[11] Much of the Keynes collection later passed to eccentric document collector Abraham Yahuda, who was himself a vigorous collector of Isaac Newton's original manuscripts.

Many of the documents collected by Keynes and Yahuda are now in the Jewish National and University Library in Jerusalem.[citation needed] In recent years, several projects have begun to gather, catalogue, and transcribe the fragmented collection of Newton's work on alchemical subjects and make them freely available for online access. Two of these are The Chymistry of Isaac Newton Project[12] supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation, and The Newton Project[13] supported by the U.K. Arts and Humanities Research Board. In addition, The Jewish National and University Library has published a number of high-quality scanned images of various Newton documents.[14]

The Philosopher's Stone

[edit]

Of the material sold during the 1936 Sotheby's auction, several documents indicate an interest by Newton in the procurement or development of the philosopher's stone. Most notable are documents entitled Artephius his secret Book, followed by The Epistle of Iohn Pontanus, wherein he beareth witness of ye book of Artephius; these are themselves a collection of excerpts from another work entitled Nicholas Flammel, His Exposition of the Hieroglyphicall Figures which he caused to be painted upon an Arch in St Innocents Church-yard in Paris. Together with The secret Booke of Artephius, And the Epistle of Iohn Pontanus: Containing both the Theoricke and the Practicke of the Philosophers Stone. This work may also have been referenced by Newton in its Latin version found within Lazarus Zetzner's Theatrum Chemicum, a volume often associated with the Turba Philosophorum, and other early European alchemical manuscripts. Nicolas Flamel, one subject of the aforementioned work, was a notable, though mysterious figure, often associated with the discovery of the philosopher's stone, hieroglyphical figures, early forms of tarot, and occultism. Artephius, and his "secret book", were also subjects of interest to 17th-century alchemists.

Also in the 1936 auction of Newton's collection was The Epitome of the treasure of health written by Edwardus Generosus Anglicus innominatus who lived Anno Domini 1562. This is a twenty-eight-page treatise on the philosopher's stone, the Animal or Angelicall Stone, the Prospective stone or magical stone of Moses, and the vegetable or the growing stone. The treatise concludes with an alchemical poem.

Newton's various surviving alchemical notebooks clearly show that he made no distinctions between alchemy and what's now considered science. Optical experiments were written on the same pages as recipes from arcane sources. Newton did not always record his chemical experiments in the most transparent way. Alchemists were notorious for veiling their writings in impenetrable jargon; Newton himself invented new symbols and systems.[15]

In a manuscript from 1704, Newton describes his attempts to extract scientific information from the Bible and estimates that the world would end no earlier than 2060. In predicting this, he said, "This I mention not to assert when the time of the end shall be, but to put a stop to the rash conjectures of fanciful men who are frequently predicting the time of the end, and by doing so bring the sacred prophecies into discredit as often as their predictions fail."[16]

Newton's studies of the Temple of Solomon

[edit]

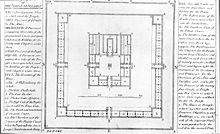

Isaac Newton's diagram of part of the Temple of Solomon, taken from Plate 1 of The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (published London, 1728)

Isaac Newton's diagram of part of the Temple of Solomon, taken from Plate 1 of The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended (published London, 1728)

Newton extensively studied and wrote about the Temple of Solomon, dedicating an entire chapter of The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended to his observations of the temple. Newton's primary source for information was the description of the structure given within 1 Kings of the Hebrew Bible as well as the Book of Ezekiel, which he translated himself from Hebrew[17] with the help of dictionaries, as his knowledge of that language was limited.[18]

In addition to scripture, Newton also relied upon various ancient and contemporary sources while studying the temple. He believed that many ancient sources were endowed with sacred wisdom[6] and that the proportions of many of their temples were in themselves sacred. This concept, often termed prisca sapientia (sacred wisdom and also the ancient wisdom that was revealed to Adam and Moses directly by God), was a common belief of many scholars during Newton's lifetime.[19]

A more contemporary source for Newton's studies of the temple was Juan Bautista Villalpando, who just a few decades earlier had published an influential manuscript entitled In Ezechielem explanationes et apparatus urbis, ac templi Hierosolymitani (1596–1605), in which Villalpando comments on the visions of the biblical prophet Ezekiel, including within this work his own interpretations and elaborate reconstructions of Solomon's Temple. In its time, Villalpando's work on the temple produced a great deal of interest throughout Europe and had a significant impact upon later architects and scholars.[20][full citation needed][21]

Newton believed that the temple was designed by King Solomon with privileged eyes and divine guidance. To Newton, the geometry of the temple represented more than a mathematical blueprint; it also provided a time-frame chronology of Hebrew history.[22] It was for this reason that he included a chapter devoted to the temple within The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended.

Newton felt that just as the writings of ancient philosophers, scholars, and biblical figures contained within them unknown sacred wisdom, the same was true of their architecture. He believed that these men had hidden their knowledge in a complex code of symbolic and mathematical language that, when deciphered, would reveal an unknown knowledge of how nature works.[19]

In 1675, Newton annotated a copy of Manna – a disquisition of the nature of alchemy, an anonymous treatise which had been given to him by his fellow scholar Ezechiel Foxcroft. In his annotation Newton reflected upon his reasons for examining Solomon's Temple:

This philosophy, both speculative and active, is not only to be found in the volume of nature, but also in the sacred scriptures, as in Genesis, Job, Psalms, Isaiah and others. In the knowledge of this philosophy, God made Solomon the greatest philosopher in the world.[22]

During Newton's lifetime, there was great interest in the Temple of Solomon in Europe, due to the success of Villalpando's publications, and a vogue for detailed engravings and physical models presented in various galleries for public viewing. In 1628, Judah Leon Templo produced a model of the temple and surrounding Jerusalem, which was popular in its day. Around 1692, Gerhard Schott produced a highly detailed model of the temple, for use in an opera in Hamburg composed by Christian Heinrich Postel. This immense 13-foot-high (4.0 m) and 80-foot-around (24 m) model was later sold in 1725 and was exhibited in London as early as 1723, and then later temporarily installed at the London Royal Exchange from 1729 to 1730, where it could be viewed for half-a-crown. Isaac Newton's most comprehensive work on the temple, found within The Chronology of Ancient Kingdoms Amended, was published posthumously in 1728, only adding to the public interest in the temple.[23]