Subscribe now for full access and no adverts

Five hundred kilometres south of Cairo, the neatly linear temple at Luxor stands in the long spiritual shadow cast by the vast complex at Karnak dedicated to the god Amun-Re – the ancient Egyptians’ supreme god and a fusion of Amun, the patron god here in ancient Waset (Luxor), and the creator god Re, whose cult centre was at Iunu (Heliopolis, outside modern Cairo).

Luxor temple is often visited as the sun sets on an exhausting day within its sprawling neighbour of Karnak. Yet, as weary visitors pass in the twilight through the iconic gateway or ‘pylon’ and along the central route, they are walking alongside many of the most famous figures in antiquity, including the Egyptian pharaohs Hatshepsut, Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun, Rameses II, and, much later, the Macedonian king Alexander the Great and, perhaps, the Roman emperor Diocletian. For this temple was dedicated to the divine Egyptian ruler or, more specifically, to the divine royal ka or ‘essence’ that flowed through the long line of Egypt’s kings.

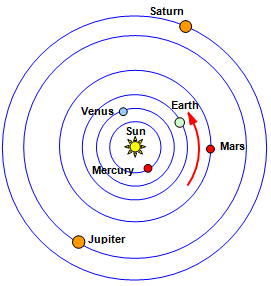

While we now borrow the convenient concept of ruling dynasties (family or political groupings) from the 3rd-century BC priest Manetho, earlier Egyptians saw only a continuous line of kings that stretched back to the rule of the god Horus and, further, to Re, the creator sun-god. Thus, the royal ka connected the ruler directly to the gods and his divine predecessors, allowing the king to exercise supreme power as an intermediary between the celestial and earthbound worlds.

The iconic pylon (gateway) of Luxor temple marked the transition of the processional way associated with the Opet festival and the beginning of the temple.

A new king’s royal ka had been with him since he was conceived, but his human form was only subsumed by the divine ka at his coronation. Henceforth, the king became semi-divine while on the throne and until his death, when he became fully divine. Most usually, after their coronation, the rulers of Egypt would come to Luxor each year in a great procession – known as the feast of Opet, which began at Karnak and ended at Luxor temple – to reaffirm the divine nature of the living king that he had inherited from his father. For this was always the Egyptian expectation: a king would die and would be succeeded by his son.

Over so many centuries, however, history could never quite force itself to be so neat. Dynastic families died out or the obvious heir might be female, a commoner, or even a foreigner. Succession to the throne might prove legitimacy in practice, but it also required a more miraculous intervention of the divine spirit. It was here at Luxor, for example, that the royal ka had descended on General Horemheb (reigned c.1323-1295 BC), a few years after the death of the childless Tutankhamun (r. c.1336-1327) that marked the end of the immediate family of the ‘heretic’ king Akhenaten (r. c.1352-1336). It was here, too, that Alexander the Great, already declared a son of Zeus-Amun by the oracle at the western oasis city of Siwa, rebuilt Amun’s shrine. It was even here that the Romans – during the reign of Diocletian (r. AD 284-305) – built a cult chapel celebrating the divine Roman emperor.

Surely, the significance of the site and its relationship to ruling Egypt was still clear one and a half millennia after the temple rose to prominence. For, although it is possible that there were cult structures here from the Middle Kingdom (1985-1650 BC), Luxor appears to have been first favoured by a great but anomalous figure: the female king Hatshepsut.

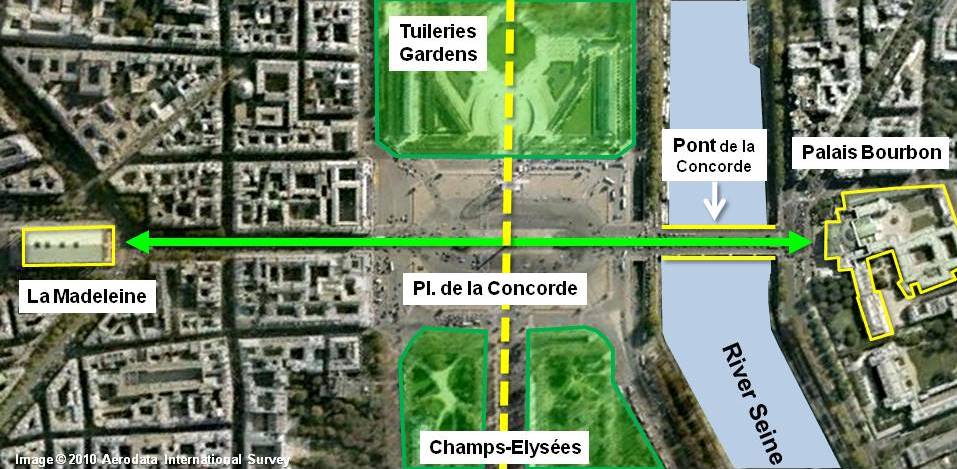

Luxor temple from the Nile, as seen in the 1830s by the Scottish artist David Roberts (1796-1864). The oldest part, the main sanctuary, appears as the low building at the furthest right (south). To the left of this is the sun court of Amenhotep III, followed by the ceremonial colonnade completed by Tutankhamun, and the northern court built by Rameses II who also built the pylon, with its characteristic obelisk. The second obelisk had already been removed by this time and is now in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Image: Public domain.

Hatshepsut was the daughter of the warrior king Thutmose I (r. c.1504-1492) and became the consort of his son and successor Thutmose II (r. c.1492-1479) – her half-brother. Following the unexpected death of Thutmose II, the throne passed to Thutmose III (r. c.1479-1425), his young son by a lesser wife. Under such circumstances, there was precedent for a dowager queen to take the role of regent, and the boy’s aunt, Hatshepsut, duly assumed this role. From the beginning, it was clear that Hatshepsut took up the role of regent in a pronounced manner, but it was not until the seventh year of Thutmose III’s reign that she had herself declared king and co-ruler (r. c.1473-1458). In justification, Hatshepsut’s propaganda asserted that her father had, in fact, chosen her as his heir and, indeed, that her mother had been impregnated by Amun-Re in the bodily form of Thutmose I and hence the royal ka had descended upon her.

Throughout her reign, Hatshepsut never lost an opportunity to affirm her legitimacy as ruler through this narrative, and her extensive development of Luxor temple is to be seen in this light. Much of the work was later replaced, but we know that Hatshepsut built six stopping points for the boat shrines – sacred vessels containing the image of Amun, his consort the mother-goddess Mut, and their son Khonsu (together the ‘Theban Triad’) – that were carried from Karnak to Luxor.

It is easiest to think of the construction of the temple as we see it today as having occurred from south to north (that is, towards Karnak). The core of the temple was built some 70 years after Hatshepsut’s reign under the great king Amenhotep III (r. c.1390-1352 BC) – Akhenaten’s father and Tutankhamun’s grandfather. This work consisted of a complex of small rooms on a raised platform at the southern end that included a separate small temple dedicated to Amenemopet – the local manifestation of Amun – and a suite of ritual rooms surrounding a central shrine where the boat shrine of Amun-Re of Karnak would be placed during the Opet festival.

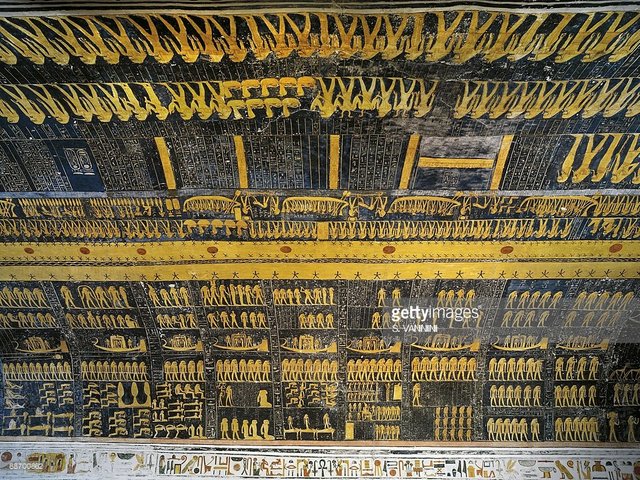

The female king Hatshepsut receives the divine royal ka from Amun-Re. The arms of the supreme god, seated behind her, form the hieroglyph for ka.

To the north of this lies a magnificent open sun court that may have formed the original gathering place in front of the sacred complex. Amenhotep III also began the temple’s distinctive processional colonnade, but this was unfinished at his death.

No building occurred here during the reign of his son Akhenaten, who had a particular antipathy to Amun-Re and his priests and instead worshipped the manifestation of the sun, the Aten, and it fell to Tutankhamun and his immediate successors to finish the colonnade. The temple stayed in this form for half a century until the great builder Rameses II (r. c.1279-1213) realigned the northern end of the temple to match the direction of the processional way from Karnak and added a further great court and the massive pylon.

For our purposes, we will allow the passage of time to stop at this point, though other kings added to the temple, particularly in the late period of pharaonic history: the association with the great, and clearly legitimate, kings Amenhotep III and Rameses II was seen as beneficial to those on shakier ground.

The late summer in ancient Egypt was a time of exhaustion and great tension as the people waited for the annual Nile flood to begin. Settled life along the Nile – known simply as iteru, ‘the river’ – was entirely dependent on the renewal brought to the fields each year by the vast quantities of silt that would cover the narrow strip of land between the river and the desert. The Opet festival, with its principal themes of rebirth and renewal, always occurred near to the beginning of the vital three-month flood season that started in what we call September.

This all-important festival in the Egyptian year gradually extended from 11 days to 24 or 27 days, and began deep in the heart of Karnak temple. To the east, behind the shrine of Amun-Re, Thutmose III had built a great Festival Hall (akhmenu). It was here that the boat shrine dedicated to the living pharaoh, and containing his ka statue, probably resided, in an area specifically dedicated to celebrating the union of the god and king. (It is also possible that the beginning of the Opet festival might have shifted to the sanctuary of Amun-Re, rather than in the festival hall, by Rameses’ reign.) From here the procession would move to the south-west of the Karnak enclosure, and, after further offerings, the boat shrine of Khonsu – the son of Amun-Re and Mut – would be added to the parade. Returning to the main north–south axis of the temple, the procession would leave Karnak along the southward route to Luxor and head for the Precinct of Mut, close to Karnak temple, where the offering process was repeated and the goddess’ boat shrine added to the proceedings.

The court built by Rameses II in front of the colonnade, characterised by these standing statues of the king, many of which were reused images of former kings.

There were now two possible routes to Luxor – either by land or, taking advantage of the prevailing wind, along the Nile – that were used at different times. It is possible that the route chosen may have depended simply on the depth of the Nile at the time. We know from the surviving reliefs along the walls of the colonnade at Luxor that the procession along the river was both colourful and loud. The processional barges would pass down the Nile under sail, with crews on the banks either side to help navigation. No doubt the large crowds on land watching the flotilla pass would have cheered the Egyptian army and exotic foreign mercenary detachments – with their standards being carried proudly to the fore – and all their accompanying horses and chariots intermingled with priests, dancers, and musicians.

The landward route would surely have seen similar scenes, but, as we have noted, there were six stopping places for the priests to rest and for offerings to be made. These six ‘way stations’ were an integral part of Hatshepsut’s design, and it is possible that the processional route was lined with sphinxes, though the avenue of sphinxes that survives at the site dates to a much later period, as it was completed under king Kheperkare Nakhtnebef (Greek: Nectanebo I; r. 380-362 BC).

In Rameses’ time, if the king and gods had travelled down the Nile, they would enter Luxor temple through a gate in the western wall to be greeted first by members of the royal family and state officials, but, if they came by land, they would enter the temple through the great pylon at the northern end that Rameses had largely completed by the third year of his reign. Great cedar flagpoles carrying pennants – features of temples that stretch back to the earliest period of Egyptian history – stood to either side of the entrance, together with four standing figures of the king together with two seated colossi. These colossal seated statues, and the two similar statues at the beginning of the colonnade, specifically represent the divine royal ka as embodied in Rameses II. In front of each of the statues before the pylon, a 25m-tall obelisk rose towards the sky.

In this scene from the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut at Karnak, priests carry the boat shrine of Amun-Re towards Luxor temple.

The whitewashed pylon was originally adorned with a colourful representation of the events of the battle of Kadesh between the Egyptian army and the Hittite empire in the fifth year of the king’s reign (c.1275 BC). A common theme of his buildings, there can be little doubt that Rameses regarded the battle as the greatest military victory in his long life, and it seems certain that the young king did indeed display great personal bravery during the battle, though the outcome was not as clear as his propaganda persistently maintained.

Once past the pylon, we enter a large court dominated by two main features. Immediately to the right lie the remains of a triple shrine that housed the boat shrines of Amun, Mut, and Khonsu. This is in the same alignment as the western gate to the quay on the Nile, suggesting that it was usual to use the river route in Rameses’ reign. Opposite the pylon is a large collection of statues bearing the name of Rameses II, many of which reused official images of previous pharaohs. Looking closely at the pillars in this court, we can also see that many of them, particularly on the east side, have a carving on them of a small bird with human arms raised in adoration. This symbol of the rekhyet- or common-folk suggests that representatives of Egypt’s people were permitted to enter the court to see the beginning of the Opet rituals.

This triple boat shrine within Rameses’ court reused material from Hatshepsut’s last resting place for the Opet procession and contained the shrines of Mut, Amun-Re, and Khonsu.

From here, the procession would leave the throng behind and, between the two great ka statues of Rameses II, enter the colonnade begun by Amenhotep III and completed by Tutankhamun and his immediate successors. The colonnade’s 14 massive open papyrus columns originally supported a stone roof and the only natural light that entered here was from stone grilles high up along the outer walls. When the procession exited the dark colonnade, the shock of the dazzling light captured by Amenhotep III’s sun court – one of the most magnificent pieces of architecture to have survived from ancient Egypt – must have been profound.

The colonnades here, around the large open court, were also roofed, and it is possible that, here too, representatives of Egypt’s people and members of the royal family gathered to see the procession of the boat shrines of the king and gods move through a multi-columned portico and ever closer to the most sacred and private part of the temple – leaving the expectant crowd outside waiting for the king’s triumphant return.

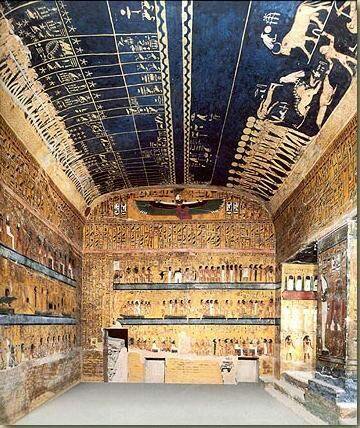

One of the most magnificent pieces of architecture to have survived from ancient Egypt, the 52m by 46m sun court is surrounded on three sides by two rows of papyrus bud columns.

The boat shrines of Mut and Khonsu were safely stored in small rooms to either side of the central door, while those of Amun-Re and the king passed on. The first room beyond has been called the Chamber of the Divine King, and it was here that the coronation rites were repeated each year. The king would turn his back towards the boat shrine of Amun-Re and a priest – physically representing the god – would place each of the crowns of Egypt on the king’s head. In this manner, the royal ka was retransmitted and the divine king reborn.

Only the king and his ka statue, the boat shrine of Amun-Re, and senior priests would now pass into the offering hall in front of the sanctuary of Amun-Re. Each offering made by the king resulted in a further divine blessing. A gift of pure water from the rising Nile would make the king himself pure; a gift of fresh flowers would make the king young; and a gift of incense would reaffirm the divinity of the king. Further reinforced, Rameses would kneel alone directly before the sanctuary and in front of the opened doors of the boat shrine of the previously hidden god. Here, this time facing Amun-Re, the god himself spiritually crowned him.

The rekhyet bird appears on a number of columns in Rameses’ court, suggesting that some representatives of the common people of Egypt were present during the Opet festival. Here, the arms are raised in adoration of the name of Rameses II.

There were probably other rituals performed within the maze of surrounding rooms, but it seems likely that one of the most important led the king from the sanctuary of Amun-Re to that of Luxor temple’s own manifestation of Amun: Amenemopet, who was a combination of Amun and the ancient self-created god Kamutef, the creator of the world. In front of Amenemopet’s shrine, the king’s offerings and prayers would simultaneously ensure the regeneration of Egypt after the inundation, the rebirth of divine kingship, and the re-energising of Amun-Re of Karnak that would be celebrated joyously and to excess on the return journey to the great complex 2.5 kilometres to the north.

It seems likely that the shrine of Amenemopet – associated with creation and fertility – remained in use well into the Roman period and for some time after the shrine of Amun-Re had fallen into disuse and the Opet festival was no longer celebrated. When the temple became part of a large Roman military camp in the 4th to 6th centuries AD, the door to Amun-Re’s sanctuary was blocked off and the divine king’s chamber in front of it was turned into a cult chamber to the divine emperor. Several Coptic Christian churches were established in the vicinity too, and today the busy mosque and shrine of Abu’l-Hajjaj – built over several centuries between 1257 and 1850 – stands high above the court of Rameses II, representing the final stage of 3,000 years of religious devotion associated with the temple.

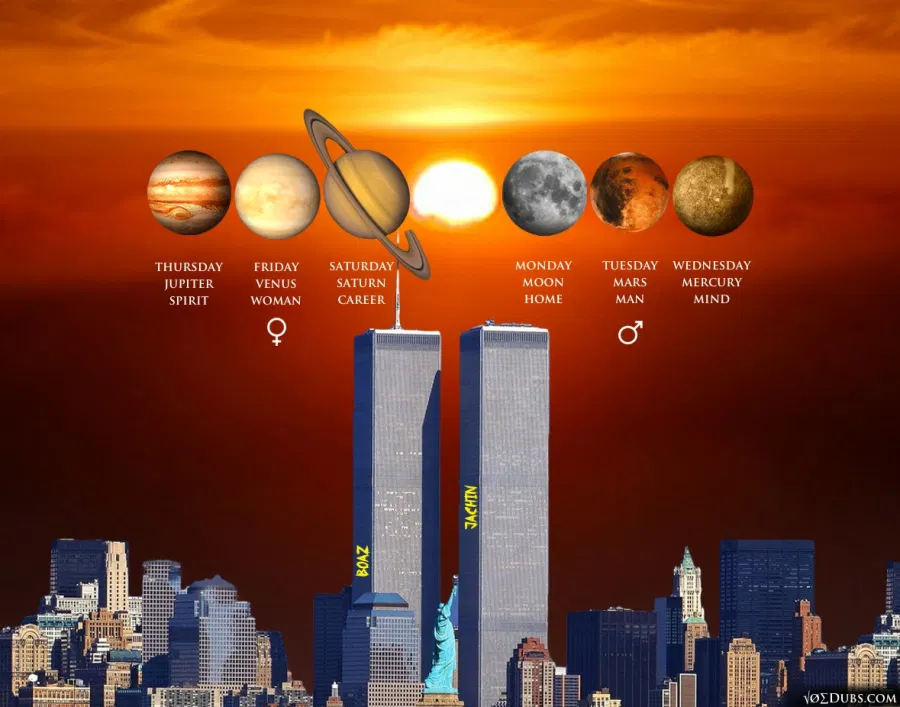

keep that date/number in mind. Looking at the towers architectural shape, we see its design is that of a square anti-prism:

keep that date/number in mind. Looking at the towers architectural shape, we see its design is that of a square anti-prism:

roll plz…They designed an upside down pentagram, the base of which is at the White House:

roll plz…They designed an upside down pentagram, the base of which is at the White House:

The iconic pylon (gateway) of Luxor temple marked the transition of the processional way associated with the Opet festival and the beginning of the temple.

The iconic pylon (gateway) of Luxor temple marked the transition of the processional way associated with the Opet festival and the beginning of the temple. Luxor temple from the Nile, as seen in the 1830s by the Scottish artist David Roberts (1796-1864). The oldest part, the main sanctuary, appears as the low building at the furthest right (south). To the left of this is the sun court of Amenhotep III, followed by the ceremonial colonnade completed by Tutankhamun, and the northern court built by Rameses II who also built the pylon, with its characteristic obelisk. The second obelisk had already been removed by this time and is now in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Image: Public domain.

Luxor temple from the Nile, as seen in the 1830s by the Scottish artist David Roberts (1796-1864). The oldest part, the main sanctuary, appears as the low building at the furthest right (south). To the left of this is the sun court of Amenhotep III, followed by the ceremonial colonnade completed by Tutankhamun, and the northern court built by Rameses II who also built the pylon, with its characteristic obelisk. The second obelisk had already been removed by this time and is now in the Place de la Concorde in Paris. Image: Public domain. The female king Hatshepsut receives the divine royal ka from Amun-Re. The arms of the supreme god, seated behind her, form the hieroglyph for ka.

The female king Hatshepsut receives the divine royal ka from Amun-Re. The arms of the supreme god, seated behind her, form the hieroglyph for ka. The court built by Rameses II in front of the colonnade, characterised by these standing statues of the king, many of which were reused images of former kings.

The court built by Rameses II in front of the colonnade, characterised by these standing statues of the king, many of which were reused images of former kings. In this scene from the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut at Karnak, priests carry the boat shrine of Amun-Re towards Luxor temple.

In this scene from the Red Chapel of Hatshepsut at Karnak, priests carry the boat shrine of Amun-Re towards Luxor temple. This triple boat shrine within Rameses’ court reused material from Hatshepsut’s last resting place for the Opet procession and contained the shrines of Mut, Amun-Re, and Khonsu.

This triple boat shrine within Rameses’ court reused material from Hatshepsut’s last resting place for the Opet procession and contained the shrines of Mut, Amun-Re, and Khonsu. One of the most magnificent pieces of architecture to have survived from ancient Egypt, the 52m by 46m sun court is surrounded on three sides by two rows of papyrus bud columns.

One of the most magnificent pieces of architecture to have survived from ancient Egypt, the 52m by 46m sun court is surrounded on three sides by two rows of papyrus bud columns.

The rekhyet bird appears on a number of columns in Rameses’ court, suggesting that some representatives of the common people of Egypt were present during the Opet festival. Here, the arms are raised in adoration of the name of Rameses II.

The rekhyet bird appears on a number of columns in Rameses’ court, suggesting that some representatives of the common people of Egypt were present during the Opet festival. Here, the arms are raised in adoration of the name of Rameses II.