|

|

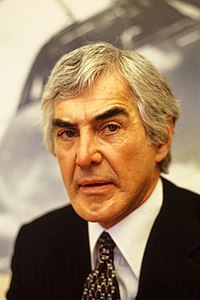

John DeLorean

John Zachary DeLorean (Detroit, 6 de enero de 1925-Nueva Jersey, 19 de marzo de 2005) fue un ingeniero, inventor y empresario estadounidense de la industria automovilística, fundador de la DeLorean Motor Company.

John DeLorean lo tuvo todo para ser uno de los hombres más importantes de la General Motors en toda su historia. Desde muy joven supo escalar hasta llegar a la vicepresidencia de la compañía; uno de los coches que le llevó a subir en la empresa fue el famoso Pontiac GTO, pero el deseo de fabricar su propio automóvil le llevó a marcharse de GM en 1973.

Para el diseño de su vehículo, el DeLorean, John DeLorean no escatimó en absoluto, y el famoso Giorgetto Giugiaro (creador de algunas joyas automovilísticas) fue el encargado del diseño del deportivo.

Sin embargo, cuando las ventas del DMC DeLorean disminuyeron enormemente, John DeLorean cayó en desgracia cuando fue arrestado en Los Ángeles en octubre de 1982 por intentar vender un maletín de cocaína por valor de 1 millón de dólares para salvar su empresa de la quiebra. El 26 de octubre de 1982 DMC entró en quiebra. En 1984 fue declarado inocente después de demostrar que un conocido suyo, James Hoffman (un informante del FBI arrestado en 1981 por tráfico de drogas) le incitó a cometer el delito.

Falleció en Nueva Jersey en marzo de 2005, a los 80 años de edad.

John Zachary DeLorean nació el 6 de enero de 1925 en Detroit, Míchigan, siendo el mayor de los cuatro hijos de Zachary DeLorean y Kathryn Pribak.1

El padre de John DeLorean, Zachary (nacido Zaharia) era un inmigrante de Rumania, originario de Şugag (distrito de Alba).2 Zachary se fue a Estados Unidos cuando tenía veinte años. Pasó algún tiempo en Montana y Gary, Indiana, antes de trasladarse a Míchigan.3 En la época en que nació su hijo John, había encontrado un trabajo como delegado sindical en la fábrica de Ford Motor Company cerca de Highland Park (Míchigan).3 Sus dificultades con el inglés y su escaso nivel educativo le impidieron conseguir puestos mejor pagados. Cuando no era requerido en Ford, trabajaba ocasionalmente como carpintero.3

La madre de John, Kathryn, era una inmigrante de Austria-Hungría que trabajaba en la División de Productos Carboloy de la General Electric, para aportar a los ingresos familiares. También tomaría cualquier trabajo que pudiese encontrar para aumentar más la renta pobre de la familia. En general ella toleraba el comportamiento errático de su esposo, pero en ocasiones se refugiaba con sus hijos en el hogar de su hermana en Los Ángeles (California), donde permanecía cerca de un año.

Los DeLorean no vivieron ciertamente en opulencia, pero en términos de depresión, las cosas indudablemente habrían podido ser mucho peores. Los alimentos y la ropa nunca faltaron en la familia y se podían permitir algún lujo pequeño, como las lecciones de música que ayudaron a John a ganar becas en las mejores escuelas de Detroit.

En 1942, Zachary y Kathryn se divorciaron. Posteriormente, Zachary se trasladó a una pensión para vivir en soledad, y debido a esto su alcoholismo empeoró. Varios años después del divorcio, John fue a visitar a su padre, encontrándolo tan perjudicado por el alcohol que apenas podían comunicarse.

John asistió a las escuelas públicas de primaria de Detroit, y luego fue aceptado en la Cass Technical High School, una escuela superior técnica de Detroit. Allí firmó un plan de estudios sobre los componentes eléctricos. Los jóvenes encontraron apasionante la experiencia de DeLorean en Cass, y sobresalió en sus estudios.

El excelente historial académico de DeLorean combinado con su talento en la música le compensó con una beca en el Instituto de Tecnología de Lawrence (ahora conocido como Universidad Tecnológica de Lawrence), un pequeño pero ilustre Colegio de Detroit que fue el alma materna de algunos de los mejores ponentes del área y diseñadores. También en este caso, DeLorean fue excelente en el estudio de la ingeniería industrial, y fue elegido miembro de la escuela en la sociedad de Honor.

La Segunda Guerra Mundial interrumpió sus estudios. En 1943 DeLorean fue reclutado para el servicio militar y sirvió durante tres años en el ejército de Estados Unidos.4 Cuando regresó a Detroit encontró a su madre y sus hermanos en dificultades económicas debido a las tensiones de Kathryn con sus problemas financieros en los ingresos. John se fue a trabajar en la Comisión de Alumbrado Público durante un año y medio con el fin de poner las situaciones financieras de su familia en tierra firme, antes de reanudar su carrera en Lawrence.

Su regreso a la universidad en 1947 vio su candidatura para presidente del Consejo de Estudiantes. Estos últimos años en Lawrence también le dieron inicio a la contribución de DeLorean en el mundo del automóvil, cuando trabajó durante un tiempo parcial en Chrysler y en un taller local de carrocería. En 1948 DeLorean se graduó con un título de Bachelor of Science en ingeniería industrial.

Luego de graduarse, DeLorean no trabajó inicialmente en ingeniería, sino como vendedor de seguros de vida. En dicho empleo, desarrolló un sistema analítico orientado a ingenieros, que le permitió vender seguros por 850 mil dólares en diez meses.5 DeLorean afirmó en su autobiografía que vendió seguros de vida para mejorar sus habilidades comunicativas.6El rubro no le interesaba a DeLorean, y a continuación ingresó en la Factory Equipment Corporation. Aún obteniendo buenos resultados financieros, dicho empleo tampoco le interesó.

Un supervisor de ingeniería de Chrysler le recomendó a DeLorean que buscara trabajo en la empresa. Chrysler tenía un centro de formación postuniveritaria, el Chrysler Institute of Engineering, que permitió a DeLorean avanzar en su educación mientras adquiría experiencia real en ingeniería automotriz.

Estudió brevemente en la Detroit College of Law, sin completar el título. En 1952, obtuvo una maestría en ingeniería automotriz en el Instituto Chrysler, y se incorporó al departamento de ingeniería de Chrysler. DeLorean tomó clases nocturnas en la escuela de negocios de la Universidad de Míchigan para obtener la maestría en administración de empresas en 1957.

Packard Motor Company

[editar]

La época de DeLorean en Chrysler duró menos de un año, terminando en 1953 cuando le ofrecieron un salario de US$ 14 000 (equivalente a US$ 135 420 en 2020) en Packard Motor Company bajo la supervisión del ingeniero Forest McFarland. DeLorean rápidamente llamó la atención de su nuevo empleador con una mejora en la transmisión automática Ultramatic, dándole un convertidor de par mejorado y rangos de transmisión doble; fue lanzada como la "Twin-Ultramatic".7

Packard estaba experimentando dificultades financieras cuando DeLorean se unió, debido al cambiante mercado automotriz posterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Mientras que Ford, General Motors y Chrysler habían comenzado a producir autos convencionales asequibles diseñados para atender a la creciente clase media de la posguerra, Packard se aferró a sus nociones de la era anterior a la Segunda Guerra Mundial de fabricar automóviles de alta gama y de lujo, diseñados con precisión. Esta filosofía exclusiva iba a pasar factura a la rentabilidad. Sin embargo, demostró tener un efecto positivo en la atención de DeLorean a los detalles de ingeniería, y después de cuatro años en Packard se convirtió en el sucesor de McFarland como jefe de investigación y desarrollo.8

Si bien aún era una empresa rentable, Packard sufrió junto con otros fabricantes independientes mientras luchaba por competir cuando Ford y General Motors se enzarzaron en una guerra de precios. James Nance, el presidente de Packard, decidió fusionar la empresa con Studebaker Corporation en 1954. Una posterior fusión propuesta con American Motors Corporation (AMC) nunca pasó de la fase de discusión.9 DeLorean consideró mantener su trabajo y mudarse a la sede de Studebaker en South Bend, Indiana, cuando recibió una llamada de Oliver K. Kelley, el vicepresidente de ingeniería de General Motors, un hombre a quien DeLorean admiraba mucho. Kelley llamó a DeLorean para ofrecerle una elección de trabajo en cualquiera de las cinco divisiones de GM.10

En 1956, DeLorean aceptó una oferta salarial de US$ 16 000 (equivalente a US$ 152 304 en 2020) con un programa de bonificación, eligiendo trabajar en la división Pontiac de GM como asistente del ingeniero jefe Pete Estes y el gerente general Semon "Bunkie" Knudsen. Knudsen era hijo del expresidente de GM, William Knudsen, quien fue llamado a abandonar su cargo para encabezar el esfuerzo de producción de movilización de guerra a pedido del presidente Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Knudsen también se graduó en ingeniería en el MIT y, a los 42 años, era el hombre más joven en dirigir una división de GM. DeLorean y Knudsen rápidamente se hicieron amigos cercanos, y DeLorean finalmente citó a Knudsen como una gran influencia y mentor. Los años de ingeniería de DeLorean en Pontiac fueron exitosos, produciendo docenas de innovaciones patentadas para la compañía, y en 1961 fue ascendido al puesto de ingeniero jefe de esa división.

El Pontiac GTO. El Pontiac GTO.

DeLorean era ampliamente conocido en Pontiac por el Pontiac GTO (Gran Turismo Omologato), un muscle car —el primero de la historia— que lleva el nombre del Ferrari 250 GTO. Como Chevrolet un poco más grande, la marca Pontiac alcanzó el tercer lugar en las ventas anuales totales de la industria en los Estados Unidos. Para resaltar el énfasis en el rendimiento de la marca, el GTO debutó como un paquete de opciones Tempest / LeMans con un motor más grande y potente en 1964. Esto marcó el comienzo del renacimiento de Pontiac como división de alto rendimiento de GM en lugar de su posición anterior sin una clara identidad de marca.

El automóvil y su popularidad continuaron creciendo en los años siguientes. DeLorean recibió el crédito casi total por su éxito —conceptualización, ingeniería y marketing— convirtiéndose en el chico de oro de Pontiac, y fue recompensado con su ascenso en 1965 para dirigir toda la división Pontiac.

A la edad de 40 años, DeLorean había batido el récord de jefe de división más joven en GM y estaba decidido a continuar con su racha de éxitos. Adaptarse a las frustraciones que percibía en las oficinas ejecutivas fue una transición difícil para él. DeLorean creía que había una cantidad indebida de luchas internas en GM entre los jefes de división, y varios de los temas de la campaña publicitaria de Pontiac encontraron resistencia interna, como la campaña "Tiger" utilizada para promover el GTO y otros modelos de Pontiac en 1965 y 1966. Además, Ed Cole tomó la decisión de prohibir varios carburadores, un método para mejorar el rendimiento del motor utilizado por Pontiac desde 1956, comenzando con dos carburadores de 4 barriles ("2x4 bbl") y Tri-Power (tres carburadores de 2 barriles ["3x2 bbl "]) desde 1957.

En respuesta al mercado de "pony cars" dominado por el exitoso Ford Mustang, DeLorean pidió a los ejecutivos de GM permiso para comercializar una versión más pequeña del coche de exhibición Pontiac Banshee para 1966. La versión de DeLorean fue rechazada debido a la preocupación de GM de que su diseño le quitara las ventas al Corvette, su vehículo insignia de alto rendimiento. Su atención se centró en el nuevo diseño del Camaro. Pontiac desarrolló su versión y se introdujo el Firebird como modelo del año 1967.

Poco después de la presentación del Firebird, DeLorean centró su atención en el desarrollo de un Grand Prix completamente nuevo, el auto de lujo personal de la división basado en la línea Pontiac de tamaño completo desde 1962. Sin embargo, las ventas estaban decayendo en ese momento, pero el modelo 1969 tendría su propia carrocería distintiva con el tren de transmisión y los componentes del chasis del Pontiac A-body de tamaño intermedio (Tempest, LeMans, GTO). DeLorean sabía que la división Pontiac no podía financiar el nuevo automóvil sola, por lo que acudió a su antiguo jefe Pete Estes y le pidió compartir el coste del desarrollo con Pontiac, teniendo una exclusividad de un año antes de que Chevrolet lanzara el Monte Carlo en 1970. El trato estaba hecho. El Pontiac Grand Prix de 1969 presentaba una carrocería afilada y un capó de 1,8 m (casi 6 pies) de largo. El interior incluía un panel de instrumentos envolvente estilo cabina, asientos de cubo y consola central. El nuevo modelo ofrecía una alternativa más deportiva, de alto rendimiento, algo más pequeña y de menor precio a los otros autos de lujo personales que estaban en el mercado, como el Ford Thunderbird, el Buick Riviera, el Lincoln Continental Mark III y el Oldsmobile Toronado. La producción del Grand Prix de 1969 terminó en más de 112 000 unidades, mucho más alta que las 32 000 unidades del Grand Prix de 1968 construidas con la carrocería Pontiac de tamaño completo.

Durante su época en Pontiac, DeLorean había comenzado a disfrutar de la libertad y la fama que venían con su puesto y pasaba gran parte de su tiempo viajando a lugares alrededor del mundo para apoyar eventos promocionales. Sus frecuentes apariciones públicas ayudaron a solidificar su imagen como un empresario corporativo "rebelde" con su estilo de vestir moderno y bromas casuales.

Incluso cuando General Motors experimentó una disminución en los ingresos, Pontiac siguió siendo altamente rentable con DeLorean y, a pesar de su creciente reputación como un inconformista corporativo, el 15 de febrero de 1969 fue ascendido nuevamente. Esta vez fue para encabezar la prestigiosa división Chevrolet, la marca insignia de General Motors.

https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_DeLorean

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

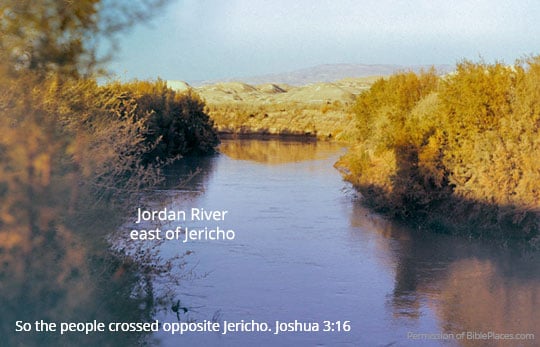

Jordan River (Utah)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

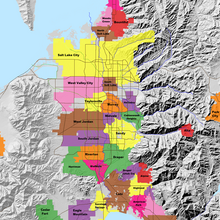

The Jordan River, in the state of Utah, United States, is a river about 51 miles (82 km) long. Regulated by pumps at its headwaters at Utah Lake, it flows northward through the Salt Lake Valley and empties into the Great Salt Lake. Four of Utah's six largest cities border the river: Salt Lake City, West Valley City, West Jordan, and Sandy. More than a million people live in the Jordan Subbasin, part of the Jordan River watershed that lies within Salt Lake and Utah counties. During the Pleistocene, the area was part of Lake Bonneville.

Members of the Desert Archaic Culture were the earliest known inhabitants of the region; an archaeological site found along the river dates back 3,000 years. Mormon pioneers led by Brigham Young were the first European American settlers, arriving in July 1847 and establishing farms and settlements along the river and its tributaries. The growing population, needing water for drinking, irrigation, and industrial use in an arid climate, dug ditches and canals, built dams, and installed pumps to create a highly regulated river.

Although the Jordan was originally a cold-water fishery with 13 native species, including Bonneville cutthroat trout, it has become a warm-water fishery where the common carp is most abundant. It was heavily polluted for many years by raw sewage, agricultural runoff, and mining wastes. In the 1960s, sewage treatment removed many pollutants. In the 21st century, pollution is further limited by the Clean Water Act, and, in some cases, the Superfund program. Once the home of bighorn sheep and beaver, the contemporary river is frequented by raccoons, red foxes, and domestic pets. It is an important avian resource, as are the Great Salt Lake and Utah Lake, visited by more than 200 bird species.

Big Cottonwood, Little Cottonwood, Red Butte, Mill, Parley's, and City creeks, as well as smaller streams like Willow Creek at Draper, Utah, flow through the sub-basin. The Jordan River Parkway along the river includes natural areas, botanical gardens, golf courses, and a 40-mile (64 km) bicycle and pedestrian trail, completed in 2017.[6]

The Jordan River is Utah Lake's only outflow. It originates at the northern end of the lake between the cities of Lehi and Saratoga Springs. It then meanders north through the north end of Utah Valley for approximately 8 miles (13 km) until it passes through a gorge in the Traverse Mountains, known as the Jordan Narrows. The Utah National Guard base at Camp Williams lies on the western side of the river through much of the Jordan Narrows.[7][8] The Turner Dam, located 41.8 miles (67.3 km) from the river's mouth (or at river mile 41.8) and within the boundaries of the Jordan Narrows, is the first of two dams of the Jordan River. Turner Dam diverts the water to the right or easterly into the East Jordan Canal and to the left or westerly toward the Utah and Salt Lake Canal. Two pumping stations situated next to Turner Dam divert water to the west into the Provo Reservoir Canal, Utah Lake Distribution Canal, and Jacob-Welby Canal. The Provo Reservoir Canal runs north through Salt Lake County, Jacob-Welby runs south through Utah County. The Utah Lake Distribution Canal runs both north and south, eventually leading back into Utah Lake.[9] Outside the narrows, the river reaches the second dam, known as Joint Dam, which is 39.9 miles (64.2 km) from the river's mouth. Joint Dam diverts water to the east for the Jordan and Salt Lake City Canal and to the west for the South Jordan Canal.[10][11][12]

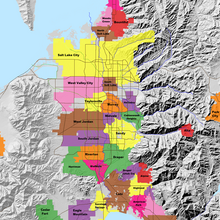

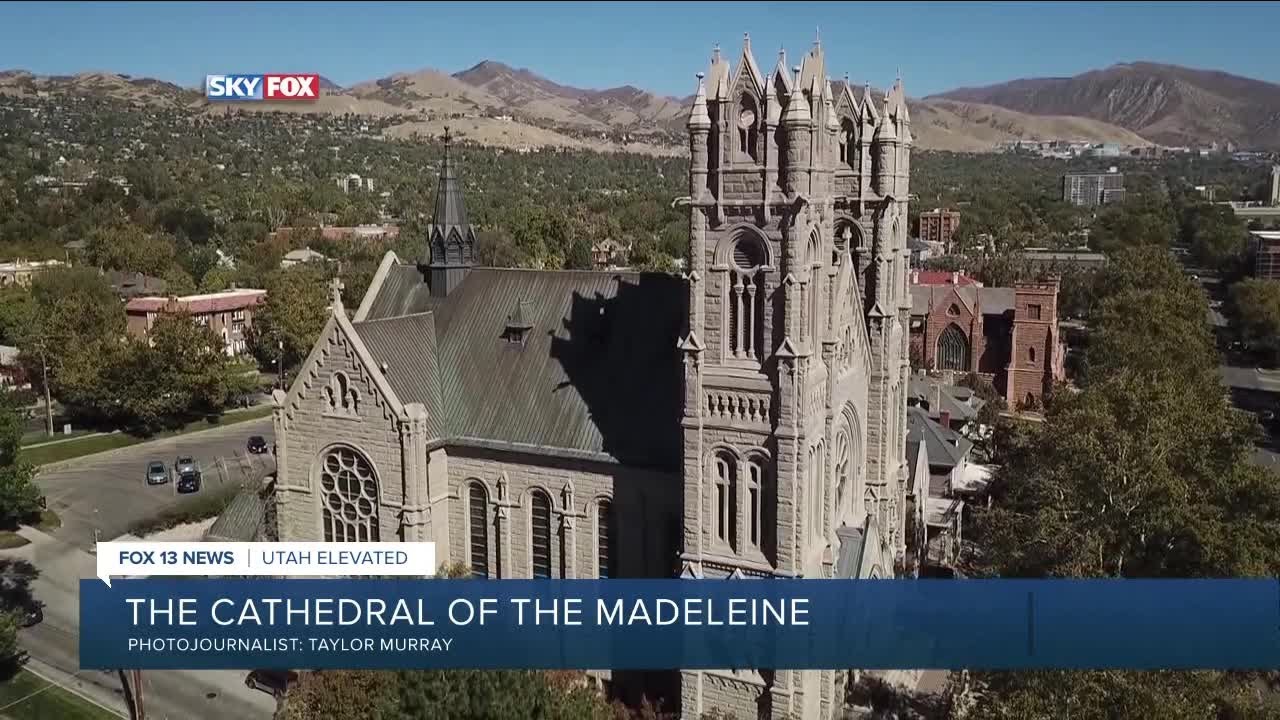

Map of the Salt Lake Valley

The river then flows through the middle of the Salt Lake Valley, initially moving through the city of Bluffdale and then forming the border between the cities of Riverton and Draper.[7] The river then enters the city of South Jordan where it merges with Midas Creek from the west. Upon leaving South Jordan, the river forms the border between the cities of West Jordan on the west and Sandy and Midvale on the east. From the west, Bingham Creek enters West Jordan. Dry Creek, an eastern tributary, combines with the main river in Sandy. The river then forms the border between the cities of Taylorsville and West Valley City on the west and Murray and South Salt Lake on the east. The river flows underneath Interstate 215 in Murray. Little and Big Cottonwood Creeks enter from the east in Murray, 21.7 miles (34.9 km) and 20.6 miles (33.2 km) from the mouth respectively. Mill Creek enters on the east in South Salt Lake, 17.3 miles (27.8 km) from the mouth. The river runs through the middle of Salt Lake City, where the river travels underneath Interstate 80 a mile west of downtown Salt Lake City and again underneath Interstate 215 in the northern portion of Salt Lake City. Interstate 15 parallels the river's eastern flank throughout Salt Lake County. At 16 miles (26 km) from the mouth, the river enters the Surplus Canal channel. The Jordan River physically diverts from the Surplus Canal through four gates and heads north with the Surplus Canal heading northwest. Parley's, Emigration, and Red Butte Creeks converge from the east through an underground pipe, 14.2 miles (22.9 km) from the mouth.[7] City Creek also enters via an underground pipe, 11.5 miles (18.5 km) from the river's mouth. The length of the river and the elevation of its mouth varies year to year depending on the fluctuations of the Great Salt Lake caused by weather conditions. The lake has an average elevation of 4,200 feet (1,300 m) which can deviate by 10 feet (3.0 m).[3] The Jordan River then continues for 9 to 12 miles (14 to 19 km) with Salt Lake County on the west and North Salt Lake and Davis County on the east until it empties into the Great Salt Lake.[7][8][11]

Discharge[edit]

The United States Geological Survey maintains a stream gauge in Salt Lake City that shows annual runoff from the period 1980–2003 is just over 150,000 acre-feet (190,000,000 m3) per year or 100 percent of the total 800,000 acre-feet (990,000,000 m3) of water entering the Jordan River from all sources. The Surplus Canal carries almost 60 percent of the water into the Great Salt Lake, with various irrigation canals responsible for the rest. The amount of water entering the Jordan River from Utah Lake is just over 400,000 acre-feet (490,000,000 m3) per year. Inflow from the 11 largest streams feeding the Jordan River, sewage treatment plants, and groundwater each account for approximately 15 percent of water entering the river.[13]

Watershed[edit]

Map of the entire Jordan River Basin

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

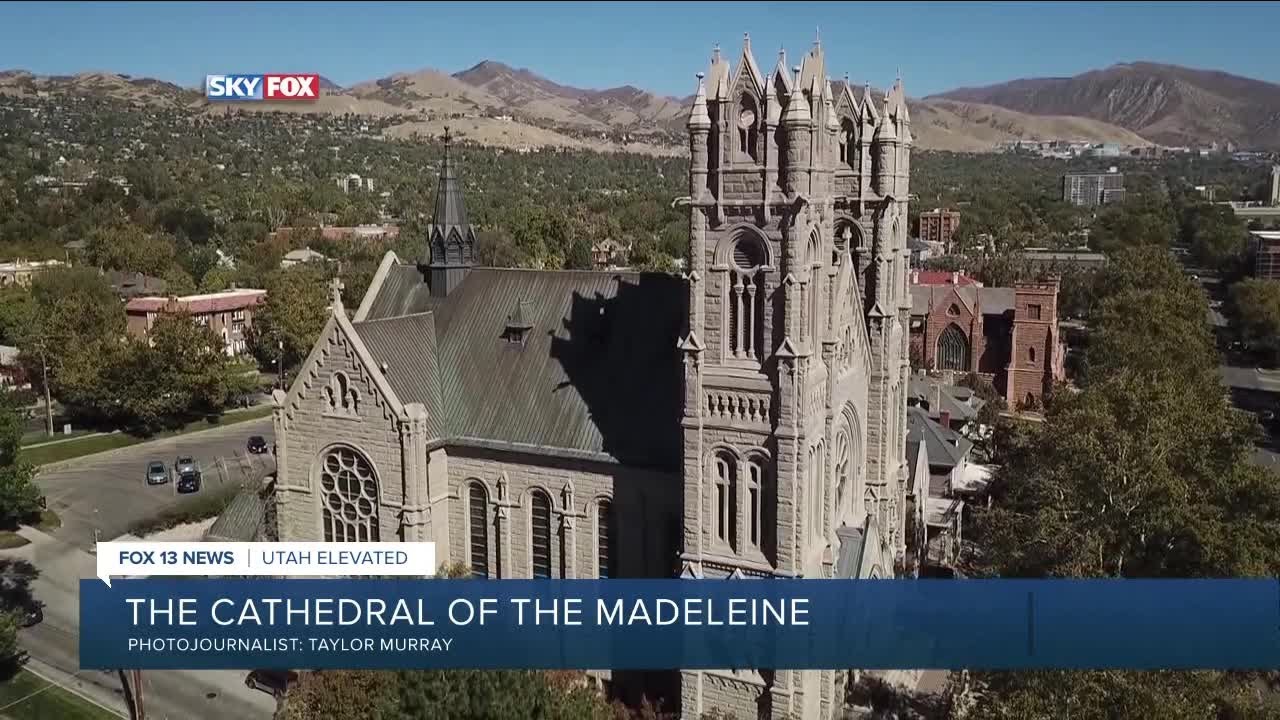

Subestación eléctrica de maniobras Magdalena I (Parque Solar Magdalena I)

NOVIEMBRE 17, 2021 PV MAGAZINE

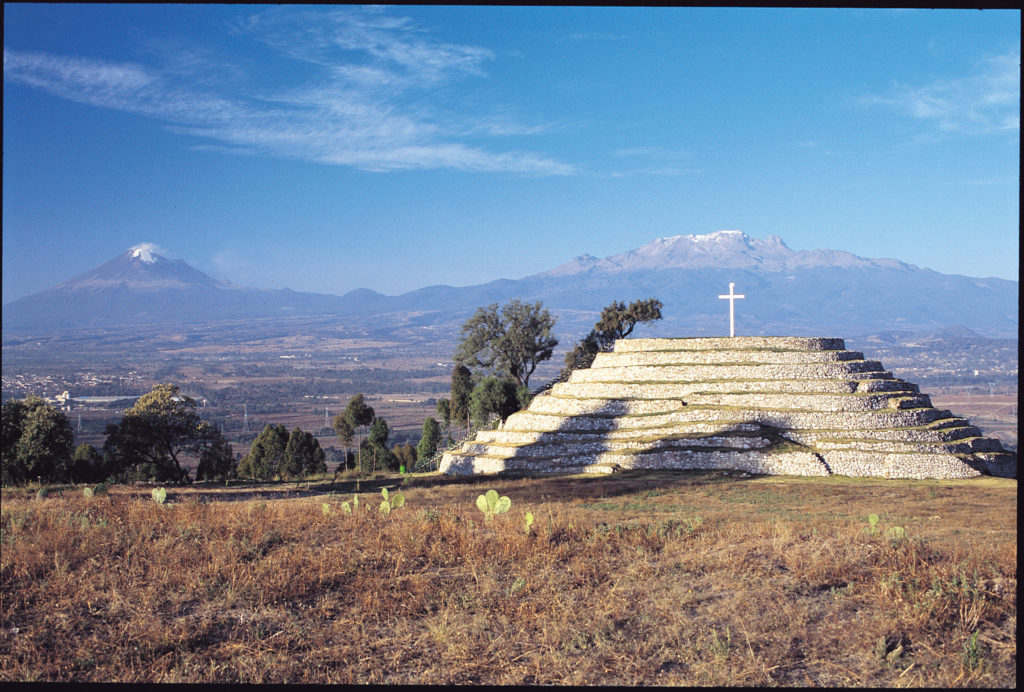

Pirámide de la Espiral Xochitecatl, Tlaxcala

Fotografía: Gobierno del estado de Tlaxcala

La Dirección General de Impacto y Riesgo Ambiental de la Secretaría de Medio Ambiente y Recursos Naturales informa que ha recibido la documentación de la firma promovente Más Energía, para el proyecto de la Subestación eléctrica de maniobras Magdalena I (Parque Solar Magdalena I).

El proyecto consiste en la construcción, operación y mantenimiento de una subestación eléctrica de maniobras, dos accesos, y una línea eléctrica de entronque de 400 Kv que se interconectará a una línea de transmisión eléctrica existente de 400 Kv propiedad de la Comisión Federal de Electricidad para desahogar la energía eléctrica que se genera en la planta fotovoltaica parque solar Magdalena I al Sistema Eléctrico Nacional.

Este contenido está protegido por derechos de autor y no se puede reutilizar. Si desea cooperar con nosotros y desea reutilizar parte de nuestro contenido, contacte: editors@pv-magazine.com.

6 Schematic representation of a cyclotron. The distance between the pole pieces of the magnet is shown larger than reality to allow seeing what is inside

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Schematic-representation-of-a-cyclotron-The-distance-between-the-pole-pieces-of-the_fig3_237993541

|

|

|

|

|

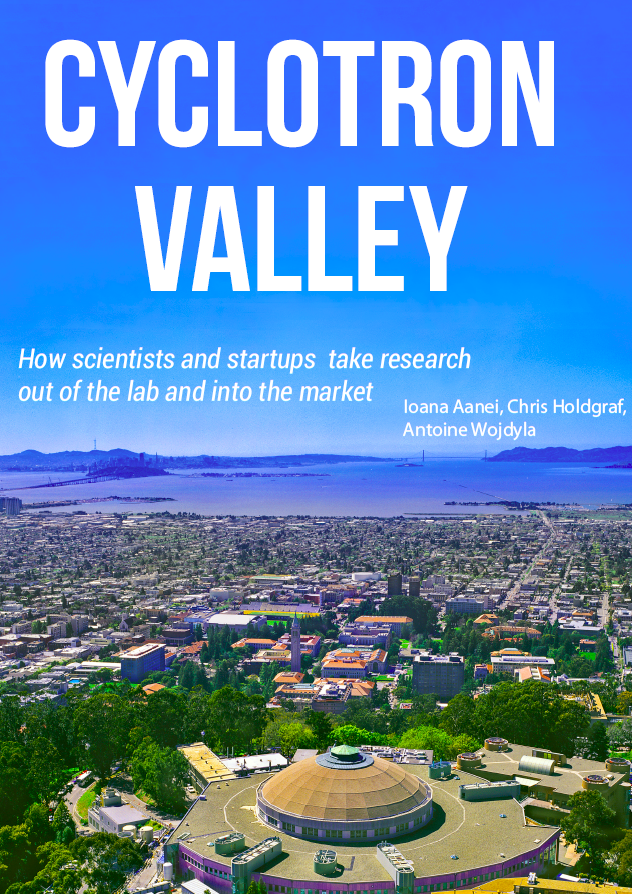

In the golden days of the microcomputer revolution, highly skilled scientists brought the Bay Area fame as an epicenter for technological innovation. Over the years, advances in hardware have given rise to advances in software, such as games and mobile apps. These tech success stories sometimes have a more “trivial” quality than Silicon Valley’s foundation in basic research and the sciences, leaving many with a lingering question: Is anyone still doing the same type of hard-fought, research-intensive work that started the silicon revolution?

Fortunately, a new kind of entrepreneur is now emerging to fill the shoes of Silicon Valley’s original trailblazers—armed with technical PhDs rather than MBAs. More and more academics are making the leap from the Ivory Tower into the world of business, rapidly growing a new, dynamic landscape of academic entrepreneurship. Hosting numerous resources for scientists hoping to make such a leap, UC Berkeley is becoming a premier gateway into the realm of science-based startups. Welcome to Cyclotron Valley.

Spot the differences: The scientist versus the entrepreneur

Understanding why entrepreneurship is growing in one of America’s most hallowed academic institutions requires understanding the career choices that academics currently face. As academic professorships dwindle and graduate student interests diversify, it is no longer true that a PhD can only be used as a stepping-stone on the road to academia (see “Oh, the places you’ll go”, BSR, Fall 2013). Fortunately, the skills painfully gained during PhD candidacy have wide applications beyond the confines of the university. The life of an academic researcher and that of an entrepreneur are more similar than you might think.

If there’s one thing that unites entrepreneurs and academics, it’s that they work hard—really hard—and are constantly tasked to solve a wide variety of problems. “In many respects, academics make wonderful entrepreneurs: they’re accustomed to resolving uncertainty, they’re familiar with building and testing hypotheses, and they’re versatile and multi-talented,” says Peter Fiske, a PhD and MBA who is now CEO of PAX Water Technologies, which develops technology for water quality improvement. While the end product of the academic lab and the startup are very different, each requires individuals to push themselves to the limit of their knowledge, time, and energy. “We actually find that PhDs and academics are much better suited for entrepreneurship than MBAs, as they come very lean in mindset and are able to do a wide variety of things,” Fiske explains. All of those hours spent in the lab are good preparation for the legwork needed to build a company from scratch.

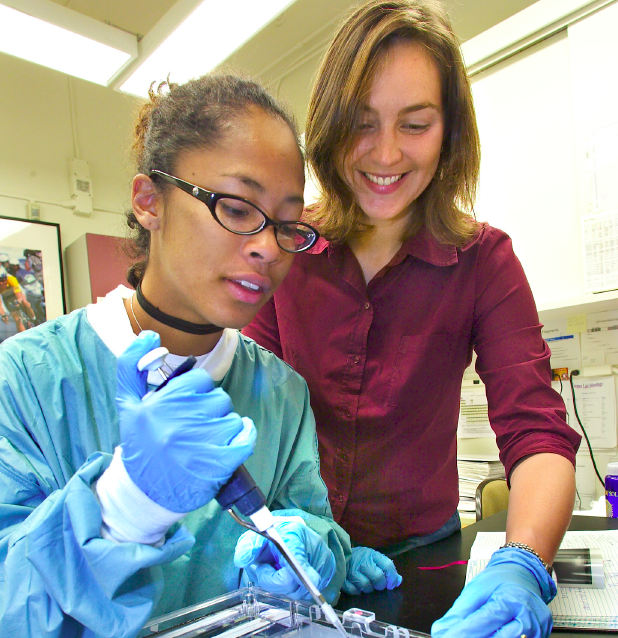

Peter Fiske, Haas MBA and CEO of PAX Water Technologies believes that PhDs are very well suited to entrepreneurship. Peter Fiske, Haas MBA and CEO of PAX Water Technologies believes that PhDs are very well suited to entrepreneurship.

Both research and entrepreneurship also require another crucial skill—flexibility. The academic must choose from many potential research paths and be prepared to alter his or her plans when experiments predictably don’t work. In the parlance of Silicon Valley, this is known as the pivot—an attempt to assess the validity of your current direction and then use that knowledge to devise another idea that works better. Entrepreneurs such as Fiske claim pivoting to be crucial to the success of any small startup: “One hundred percent of the time, an initial idea has to make a pivot, and you have no idea of what is valuable until you get out and talk to people, especially when you come from academia.” Pivoting comes hand in hand with another important skill: iteration. In science, iteration involves repeating an experiment over and over, making tweaks until the experiment works. Simply put, both the entrepreneur and the scientist must be ready to fail early and fail often. As inventor Thomas Edison purportedly wrote, “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.”

While entrepreneurship and academia share many of the same struggles, they share a key benefit: the freedom to follow a personal vision. “The reality is that there isn’t enough funding for curiosity-based science,” says Jill Fuss, a former researcher at LBNL who ventured into the entrepreneurship world to start her company, CinderBio, which produces industrial cleaning enzymes from microbes living in the most extreme environments on the planet, like volcanic springs. For those who wish to carve out their own path through discovery, entrepreneurship may offer an alternative to dwindling academic options. But if academia and entrepreneurship are so similar, what are the challenges to bringing your research from the lab to the startup?

Bumps in the road

In spite of the significant overlap between the lives of entrepreneurs and academics, there are also key differences. Most of these revolve around three main points: management, communication, and culture.

We’ve all heard the stereotype of the dedicated scientist who can’t explain their work to their peers, much less a lay audience. Though this might not seriously hinder an academic career, it becomes much more problematic outside the Ivory Tower. While the scientist excels at bolstering detailed claims using painstakingly collected data, the entrepreneur must be a master of the elevator pitch. This form of short, clear communication is often overlooked in the scientific community, but there are many avenues for learning it in academia. Organizations that aim to communicate scientific research to a broader audience are a great resource for jargon-happy scientists hoping to soften their technical delivery.

Even if academics know how to communicate effectively with the outside world, they often don’t know how to navigate the murky waters of networking. Many scientists dread being scooped, or beaten to the scientific punch by a competing lab that publishes first. As a result, academics are often highly guarded when talking about their work to others. However, in the world of entrepreneurship, it is common to present even half-baked ideas, while omitting key specific technical details in order to solicit feedback and understand an idea’s likelihood of success. Networking and broadly sharing new ideas are crucial to success in the startup world. As Fuss explains, “growing a network is essential, as well as learning the jargon used in the startup world.” She also highlights the importance of presentation skills, including elements often considered unnecessary in academia, such as graphic design. These skills might be picked up by taking classes or participating in organizations that focus on communication, journalism, and data science.

Finally, there is the poorly-defined culture shock that comes with leaving the bubble of academia and entering the world of business. This may be reflected in a simple lack of business acumen. For example, scientists often suffer from misconceptions about the size of a market for an invention, or the likelihood that it could go to production. Fortunately, most modern universities like UC Berkeley have a variety of organizations and administrative offices equipped to teach the language of the business world.

Jill Fuss(right) is co-founder at CinderBio, a startup that blossomed out of a summer project at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. Jill Fuss(right) is co-founder at CinderBio, a startup that blossomed out of a summer project at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

To help evaluate the feasibility and the market potential of a product, it is often a good idea to team up with someone more business-oriented. “Starting a company is not innate, there are many things that scientists need to learn,” says Peter Minor, co-founder of the CITRIS Foundry, an organization at UC Berkeley that supports early stage startups. Yet Minor is optimistic about scientists’ ability to succeed, explaining, “I’ve noticed that when scientists receive the proper training, [they] form incredible entrepreneurs.” Nevertheless, for would-be entrepreneurs, there is no single route to success.

From bench to business

For scientists aspiring to enter the world of business, the road to entrepreneurship may not be straight, but a good idea can go far. Take Will Hubbard, who studied industrial engineering and economics at Berkeley. During a class, he met soon-to-be cofounder Brian Kim, and after a few conversations they had the “aha!” moment that led to their company. “We saw the potential of this new technology to provide low-cost, low-power sensors,” Hubbard describes. They took their skills out of the lab and started ChemiSense, a company that makes portable sensors to detect air pollution.

The two turned to the resources available at Berkeley, building a company while simultaneously completing their studies. They joined an incubator called VentureLab, a collection of early-stage companies and experienced advisors that provide seed funding, training, and an environment where startups can thrive. Hubbard and Kim also obtained a business certificate from the Berkeley Center for Entrepreneurship. The center gave them the tools and experience needed to accelerate the growth of their company once their research was finished.

Yet despite these resources, fully benefitting from Berkeley’s entrepreneurial programs required some digging. “There were many resources, but they were spread all over the place,” Hubbard says. Fortunately, in recent years a number of organizations have sprung up to connect students with those resources. Today, ChemiSense is a member of the California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences (QB3) Garage at Berkeley, an incubator that provides equipment and lab space for research-intensive startups. As Hubbard explains, “The resources that QB3 provided, both in terms of the physical materials and the people we’ve come to know along the way, have helped a tremendous amount with growing our technology, product, and company.”

The science behind Cinderbio, on the other hand, grew out of a short-term academic project that Jill Fuss oversaw. “The project was initially given to a summer student co-mentored by me and the other co-founder,” Fuss recalls. The project entailed the study of exotic microbes and was funded by the Department of Energy. After years of research, Fuss explains that “[we were] amazed to see how active and stable were the enzymes [we] produced.” However, their grant was coming to an end, and “after the money from the grant ran out, we decided to continue the idea and start a company.” They realized that the enzymes they were using in their research were resilient enough to be used to cleanse toxic chemicals in harsh, industrial conditions. Cinderbio then applied to startup competitions and received enough advice and cash prizes to get off the ground.

But what happens when there isn’t a clear, direct path to a successful company? Many scientific startups show promise but require years of painstaking, costly research to develop their product. The delay between early-stage research and profit is even referred to as the Valley of Death, and it can stop a budding company in its tracks. Because traditional investors favor projects that become profitable quickly, there is a vacuum of support for these highly technical projects.

To help bridge the Valley of Death for nascent startups, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory hosts several facilities that allow the free use of their resources, such as the Advanced Light Source or the Molecular Foundry, by mid-stage startups that have submitted a business proposal. In fact, national laboratories are legally obliged to foster economic activity for the public good alongside their pursuit of scientific knowledge. Last year, a new program called “Cyclotron Road” was launched at Berkeley Lab to support entrepreneurial scientists who are developing energy technology ideas that are beyond the academic research phase but still too risky to attract funding from investors. Cyclotron Road is effectively the reverse of a traditional “spin out” model; prospective founders “spin in” to the National Lab, where their technology is developed using research-grade facilities alongside experts in the field. The hope is that this environment will improve the chances of nascent technologies succeeding in the marketplace. “The program was developed as an impulse response to what was happening in the marketplace for research and development,” says Sebastien Lounis, co-founder and director of communications at Cyclotron Road. “In the mid-2000s, there was a huge influx of venture capital into all kinds of early-stage cleantech start ups, but very few ended up being successful using that financing model.” As this funding began to dry up, it created a need for an organization like Cyclotron Road. As Lounis puts it, “To solve the biggest problems, we also need a home for the most talented people.”

Perilous as it may be, the Valley of Death is only one of the many challenges that young companies must overcome to survive. Scientist-entrepreneurs must also navigate the unfamiliar territory of the legal system. Choices they make in early-stage incorporation paperwork can have profound implications on how they later attract future investors and pay taxes. They also need to worry about intellectual property and even visa issues, all of which impact whether a startup stays afloat. Eventually, though, even established companies must grapple with the reality of all businesses: maintaining the bottom line.

Paying the bills

The key goal for any business idea comes down to two related issues: what form will it take and how will it secure funding? Academic research destined for commercial enterprise was once deemed simple “intellectual property”, and business applications were considered to be outside the purview of universities. Consequently, UC Berkeley has had a history of selling its research ideas to pre-existing companies rather than spinning off independent companies of its own. In recent years, the university has changed directions by freeing up money to directly support entrepreneurs.

A large part of funding for early stage research ventures comes from grants such as the Small Business Innovative Research (SBIR) program. These are grants specifically designed to base a startup on ideas generated from academic research, and offer support in proportion to a company’s growth. Importantly, these grants are “non-diluting”, meaning the founder retains full ownership of the funded company. This contrasts with private funding, which is often exchanged for shares in a company. Such no-strings-attached “free money” is essential to grow a company that has yet to build a product. As Fuss’ company grew from an idea to an established startup, phase I grants from SBIR funded CinderBio’s research when the company’s earlier cash prizes ran out. As the company matures further, Fuss will apply for phase II of SBIR’s tiered funding to match CinderBio’s growth.

While university grants can be crucial during the early years of young business, sometimes this support is insufficient to drive a resource-intensive project. Regular banks will not provide loans to risky ventures, so researchers often end up resorting to private funding of their ventures. For example, “business angels” are individuals with an interest in promoting entrepreneurship in a specific area and who provide seed funding to a select group of newborn companies. Similarly, venture capitalists (VCs) are investors who take risks by investing in a larger number of young promising companies in the hopes that one will be successful. The premise is that typically one success will offset the losses of others many times over.

In contrast to the last decade’s surge of software-based startups, an increasing number of business angels and VCs are promoting technological companies on account of their “tangible assets”. These are products, infrastructure, and intellectual property that are tied to physical objects that can be sold or traded. By possessing tangible assets, newer tech companies are arguably less sensitive to the ebb and flow of the stock market. Other investors are simply motivated by the desire to give back to society and bring innovation out of the lab. “Silicon Valley initially thrived on research-heavy, capital-intensive innovation, and is now coming back to it,” says Gerry Barañano, director of the Tech Futures Group, which offers free assistance to young startups. Berkeley now has specific groups of VC and angel funds, like the Batchery, that specifically fund technology-based venture.

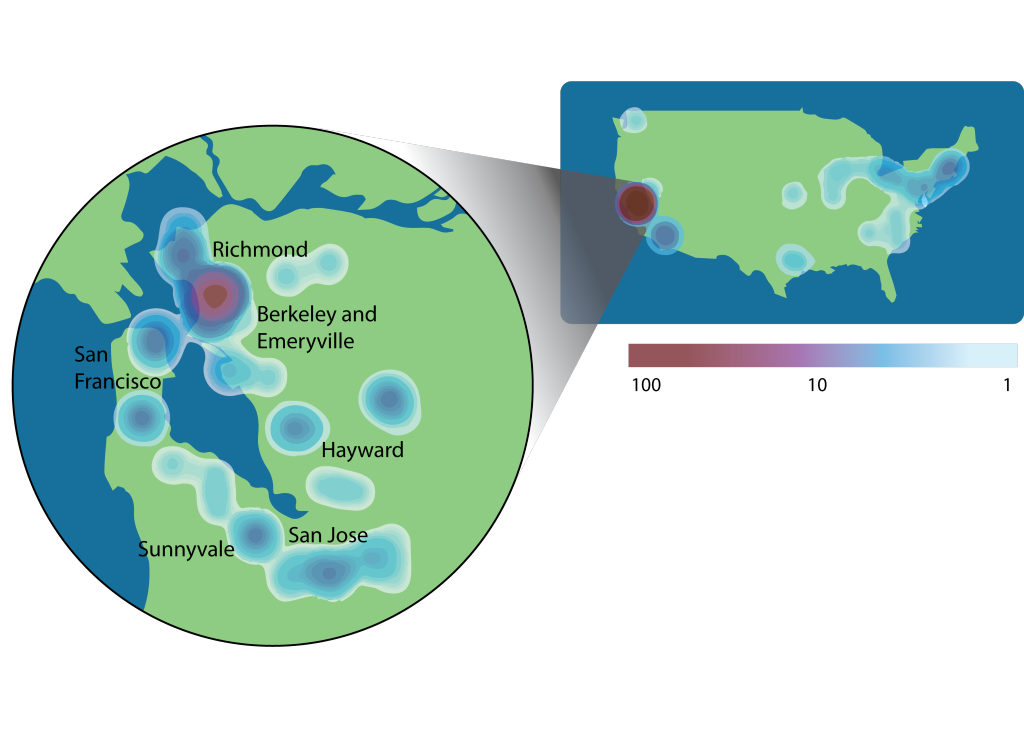

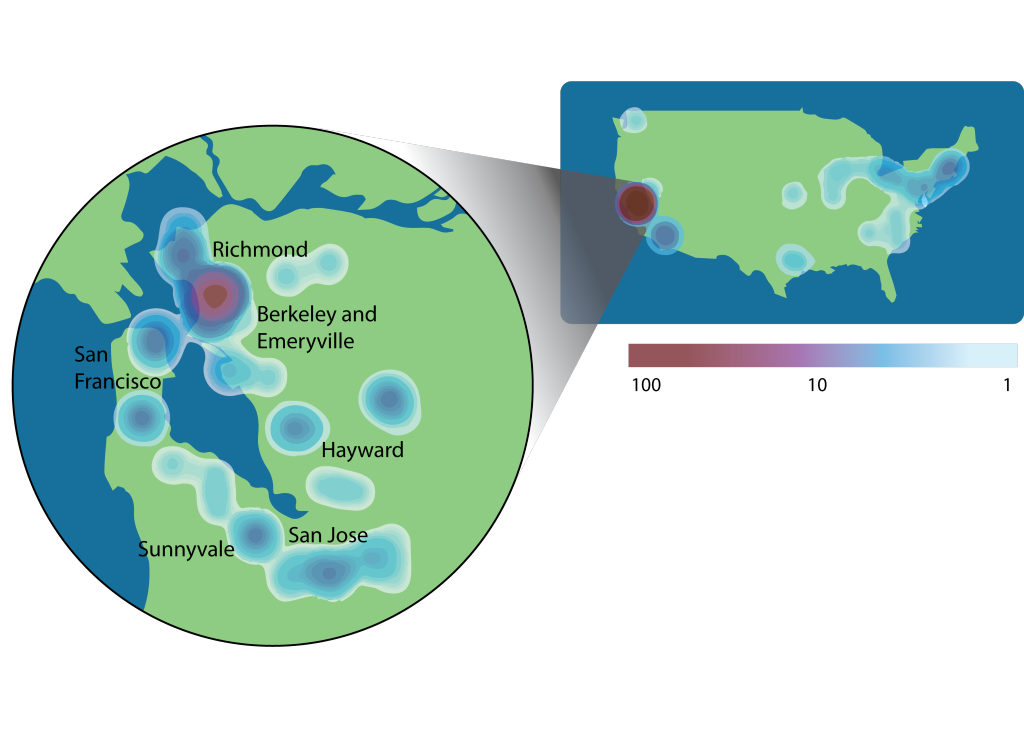

A heatmap of the number of startups with UC Berkeley-associated intellectual property reveals an interesting pattern. While many startups are located in the South Bay - the traditional Silicon Valley hotspot - there is an intense concentration of Berkeley associated startups in the East Bay. Particularly in the cities of Berkeley and Emeryville. A heatmap of the number of startups with UC Berkeley-associated intellectual property reveals an interesting pattern. While many startups are located in the South Bay - the traditional Silicon Valley hotspot - there is an intense concentration of Berkeley associated startups in the East Bay. Particularly in the cities of Berkeley and Emeryville.

A new academic path

While it isn’t possible, or advisable, for every graduate student or postdoc to become an entrepreneur, it is important to revisit the role of entrepreneurship in the academic world. Whether it is starting a company, joining a startup in need of brainpower, or simply interacting with and learning from the business community at the university, taking an entrepreneurial approach to science can be uniquely rewarding. Minor, who has seen many graduate students become entrepreneurs, points out that “investigating entrepreneurship while investigating science is a highly synergistic experience.”

Taking one’s research out of the laboratory and into the business community will always be a challenge. In the past, this was because of cultural factors such as a lack of institutional support or an academic climate that discouraged business ventures. Now, resources within UC Berkeley and the Bay Area have given academics the tools needed to overcome these barriers, allowing them to focus on growing a successful business. While basic research will always be a core goal of the university, UC Berkeley scientists can now use their expertise to make the world a better place through business innovation as well. As Ed Zschau, a famous entrepreneur in the world of high-tech said: “Entrepreneurship is not about starting a company. Entrepreneurship is an approach to life. It is about leaving footprints.”

- Ioana Aanei is a graduate student in the department of chemistry, Chris Holdgraf is a graduate student in the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute, and Antoine Wojdyla is a postdoctoral researcher in materials science at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

This article is part of the Fall 2015 issue.

https://www.berkeleysciencereview.com/article/2015/11/20/cyclotron-valley |

|

|

|

|

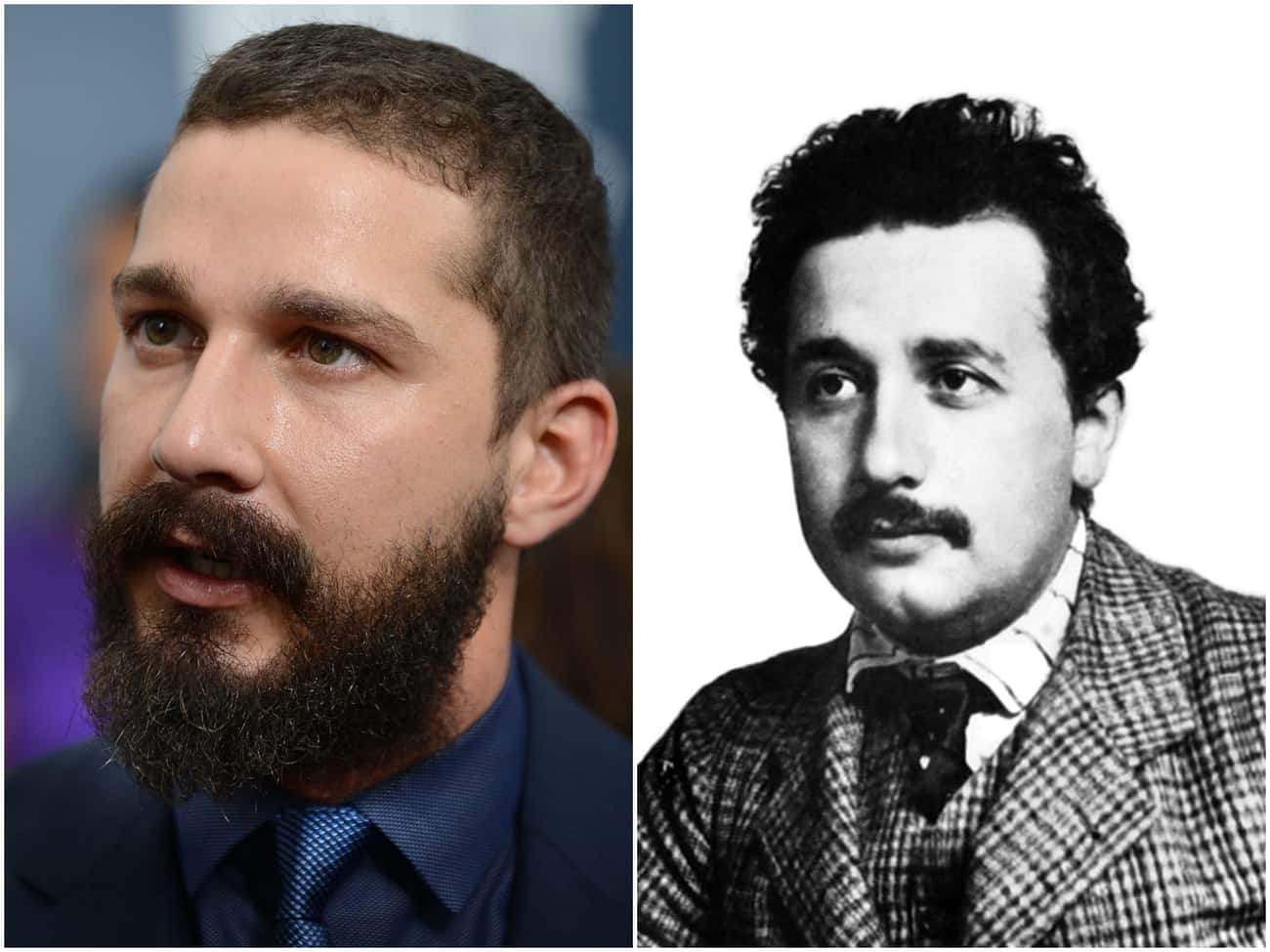

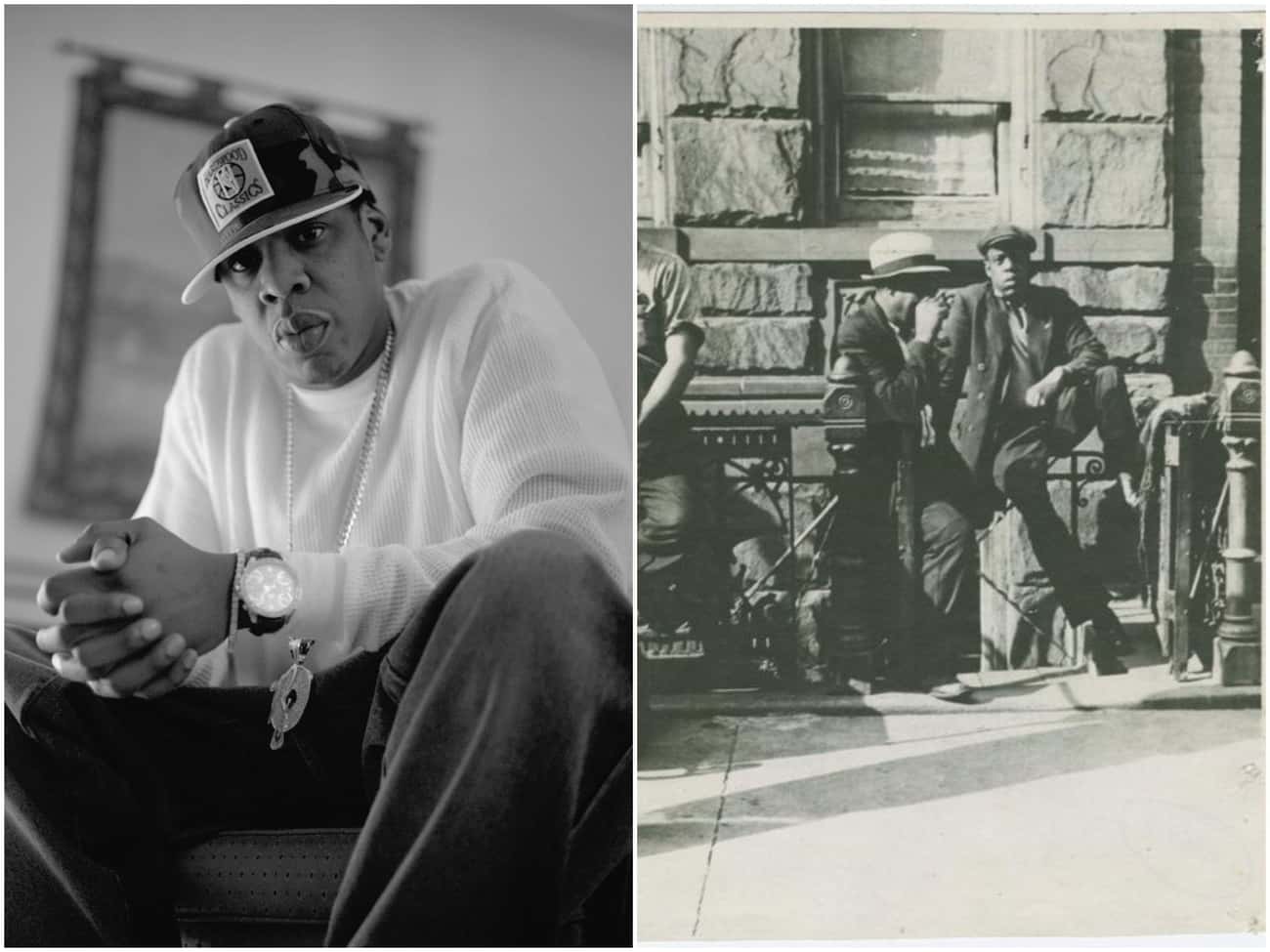

Top 10 Celebrities with Doppelgangers from the Past

Have you ever wondered why someone who lived over 100 years ago looks like your twin? Well, it’s more common than you think, and science has been delving into the doppelganger mystery. So today we give you celebs that share eerily similar mugs with strangers from yesteryear.

The following is a list of today’s well-known, elite celebrities and the mysterious photos unearthed of what seems to be near carbon copies of them from different points in our history. And many of the images are dated well over 100 years. Whether it happens to be a long-lost family member that somehow was knocked out of the family tree or perhaps a more illogical, fantastic reason for the occurrence, we may never know.

Here are 10 crazy occurrences of celebrity doppelgangers.

RELATED: TOP 10 WORST CELEBRITY ADVERTS

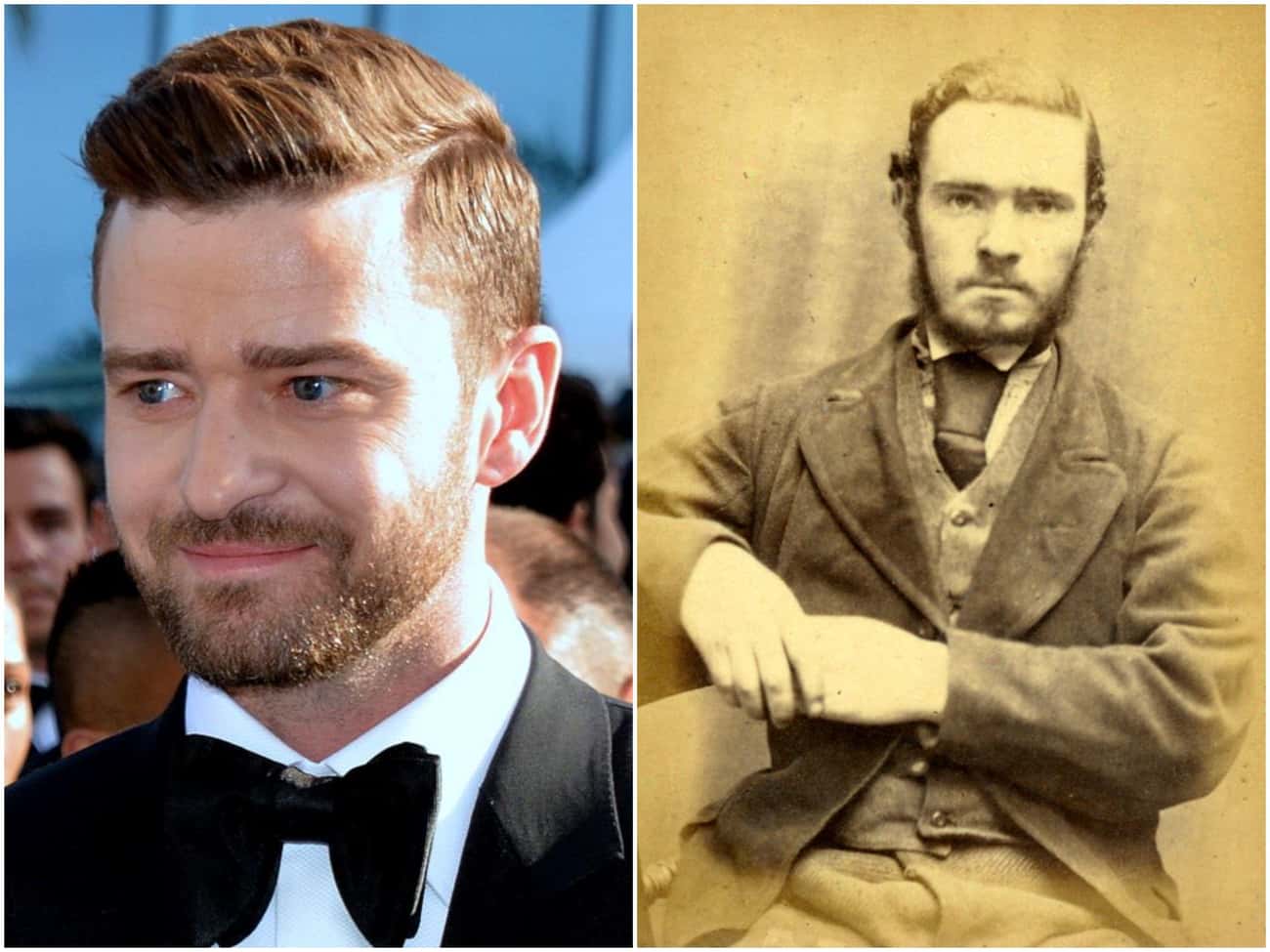

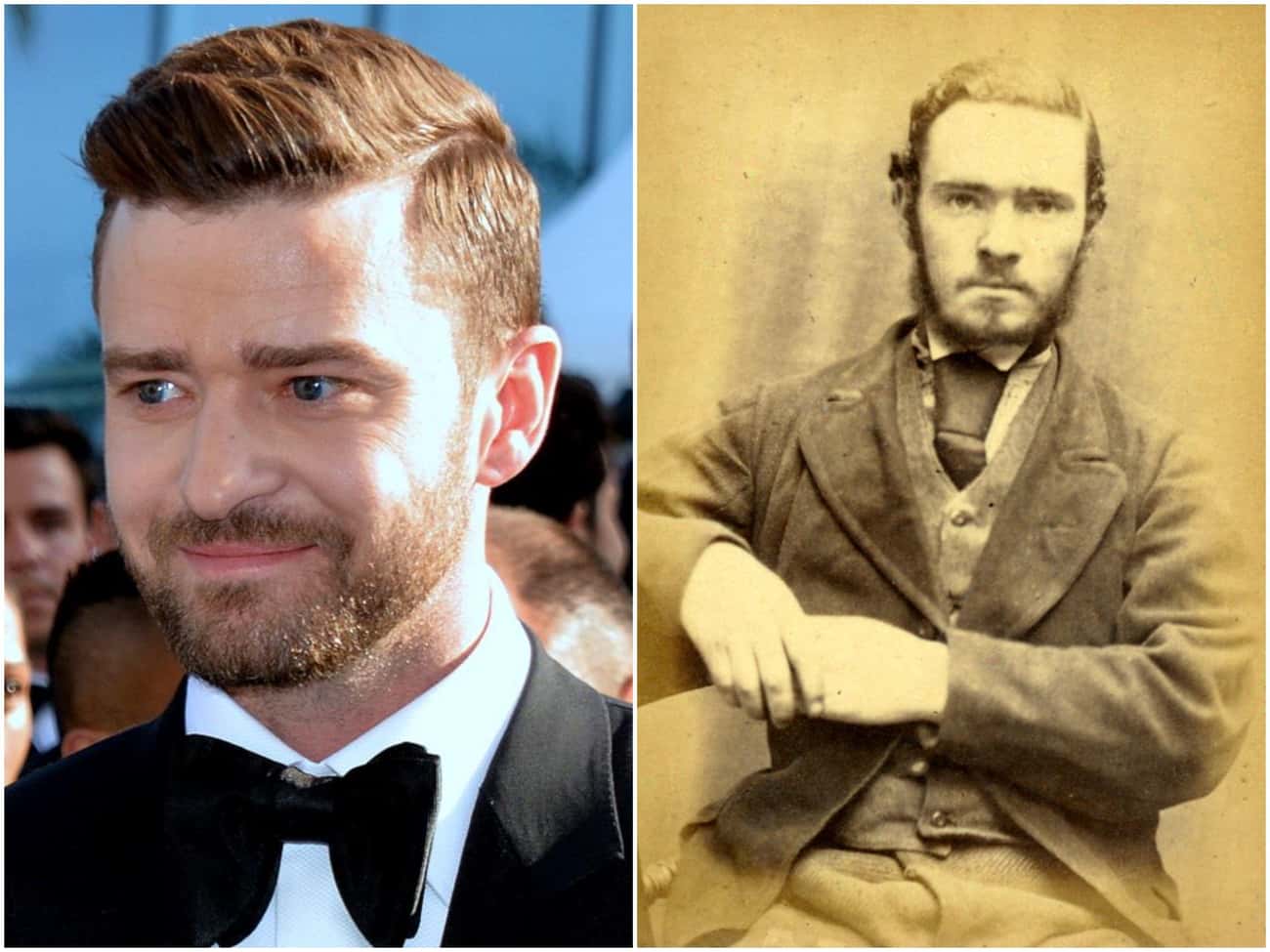

10 Justin Timberlake/Man in Mugshot

The uncanny resemblance, to say the least, between JT and this man depicted in an image from the 1870s is freakishly similar. There’s no name for this mystery man; however, I’d be willing to bet that they might share the same DNA. Supposedly a miner from Liverpool, this formal photo was his mugshot. I wonder if this criminal was aware that committing crimes was a bad idea because “what goes around, comes around.” As for Justin, he’s avoided the criminal justice system over the years.[1]

9 Nicolas Cage/Civil War Soldier

Nic Cage responds to vampire rumors on Letterman

Our next celebrity look-alike is Nicolas Cage and this dapper gentleman from the 1860s. Like the previous entry, there is no concrete identifying information for the gentleman in the photo, although he is thought to be a Civil War soldier. Other than that, his identity is a big fat unknown. As for Cage, well, there have been rumors about him, including a bizarre theory that he’s a bloodthirsty vamp. I don’t know about all that; however, these two men look shockingly identical to one another. Maybe he is an undead vampire after all![2]

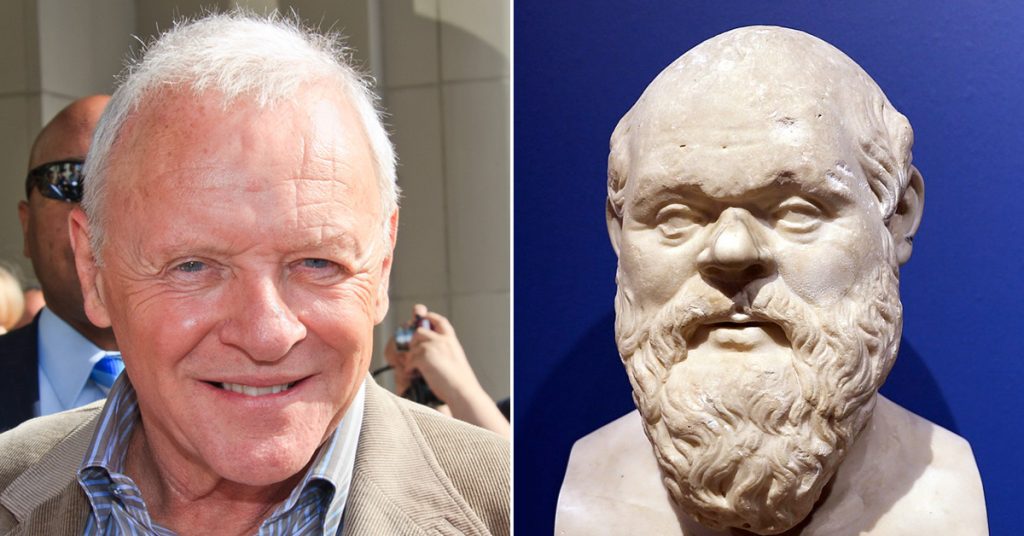

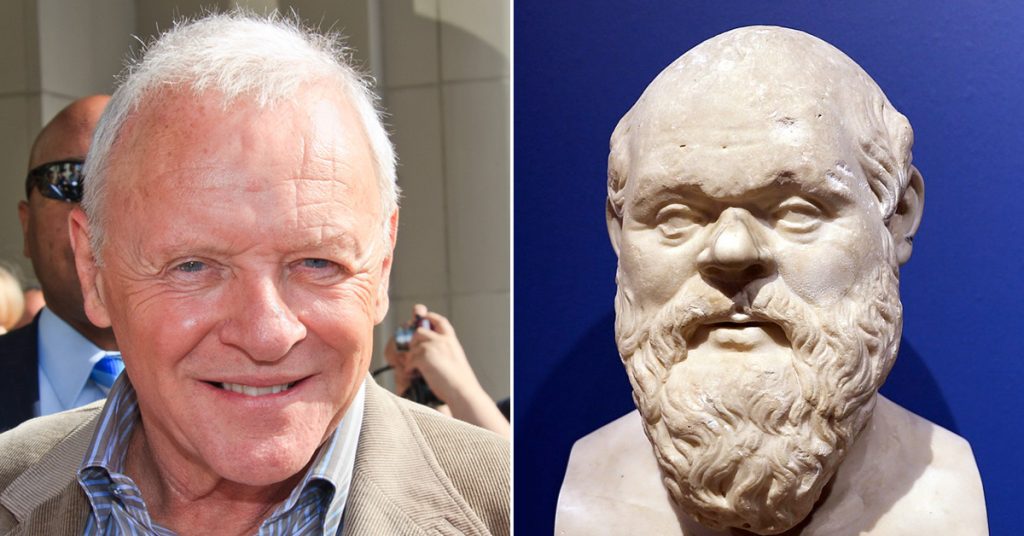

8 Anthony Hopkins/Socrates

This entry on the list is a tad bit different from the others because acclaimed actor Anthony Hopkins resembles a stone bust of the Greek philosophical powerhouse Socrates, who was believed to live somewhere around 467-399 BC. Although he wrote nothing in his life, according to scholars, he is still considered to be one of the greatest, most impactful philosophers in history. In today’s day and age, he would have had TikTok on lock, trending with his different views on various subjects.

You can see these fellas have similar button noses and wild beards. You can see why people tend to make the comparison. I wonder if Anthony Hopkins will ever play this toga-wearing, ancient Greek symbol.[3]

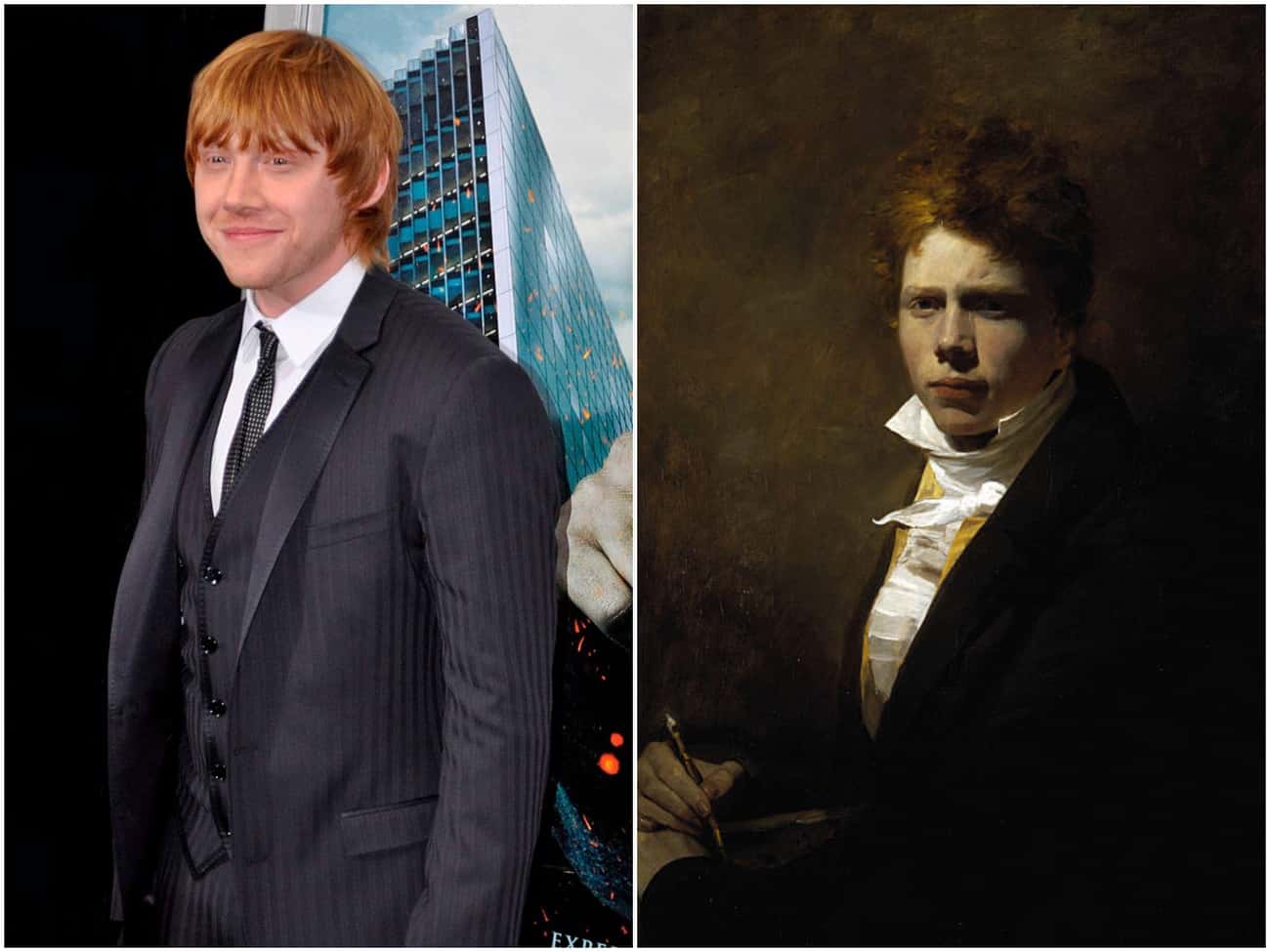

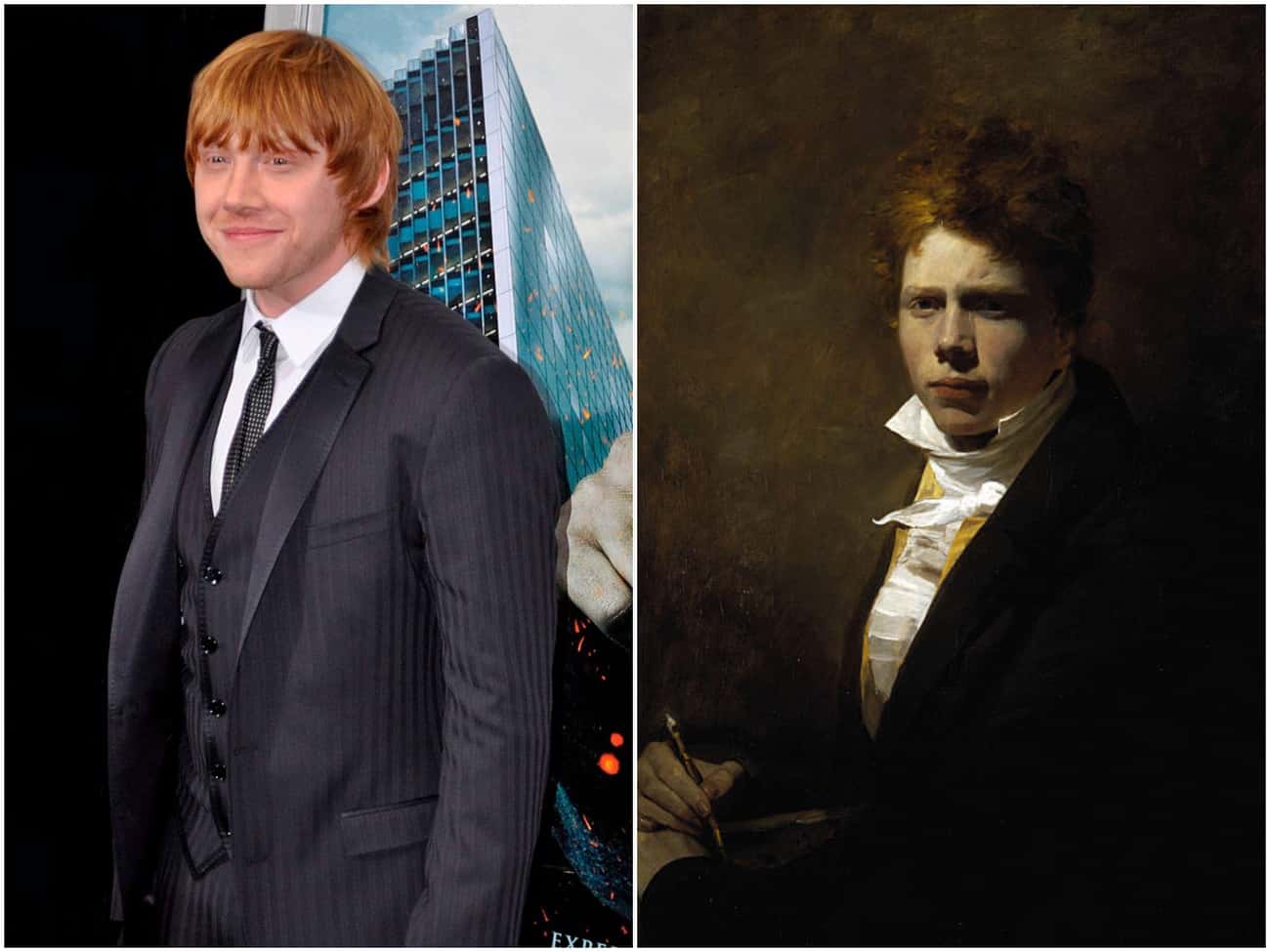

7 Rupert Grint/Sir David Wilkes

This is an unbelievable find! These two men’s facial features are so similar it’s eerie. The man on the left is none other than Rupert Grint, aka Ron Weasley from the Harry Potter movie franchise. The man on the right is Sir David Wilke, a Scottish painter born in the 1780s.

He painted historical scenes and locations from his travels abroad. He was appointed Painter to the King in 1830 and knighted in 1836. I mean, these two guys look like they could be twinning it. It’s a truly incredible resemblance.[4]

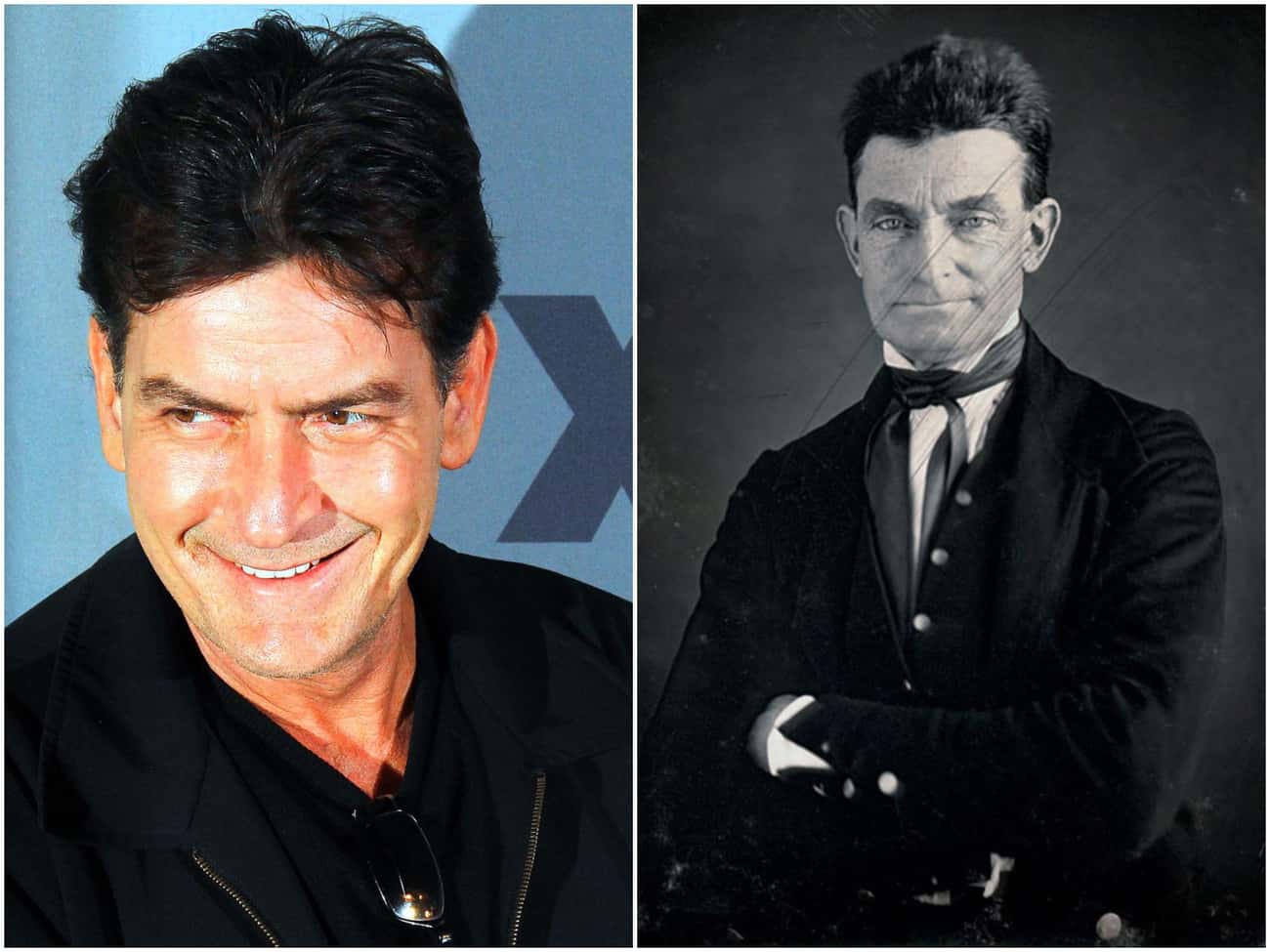

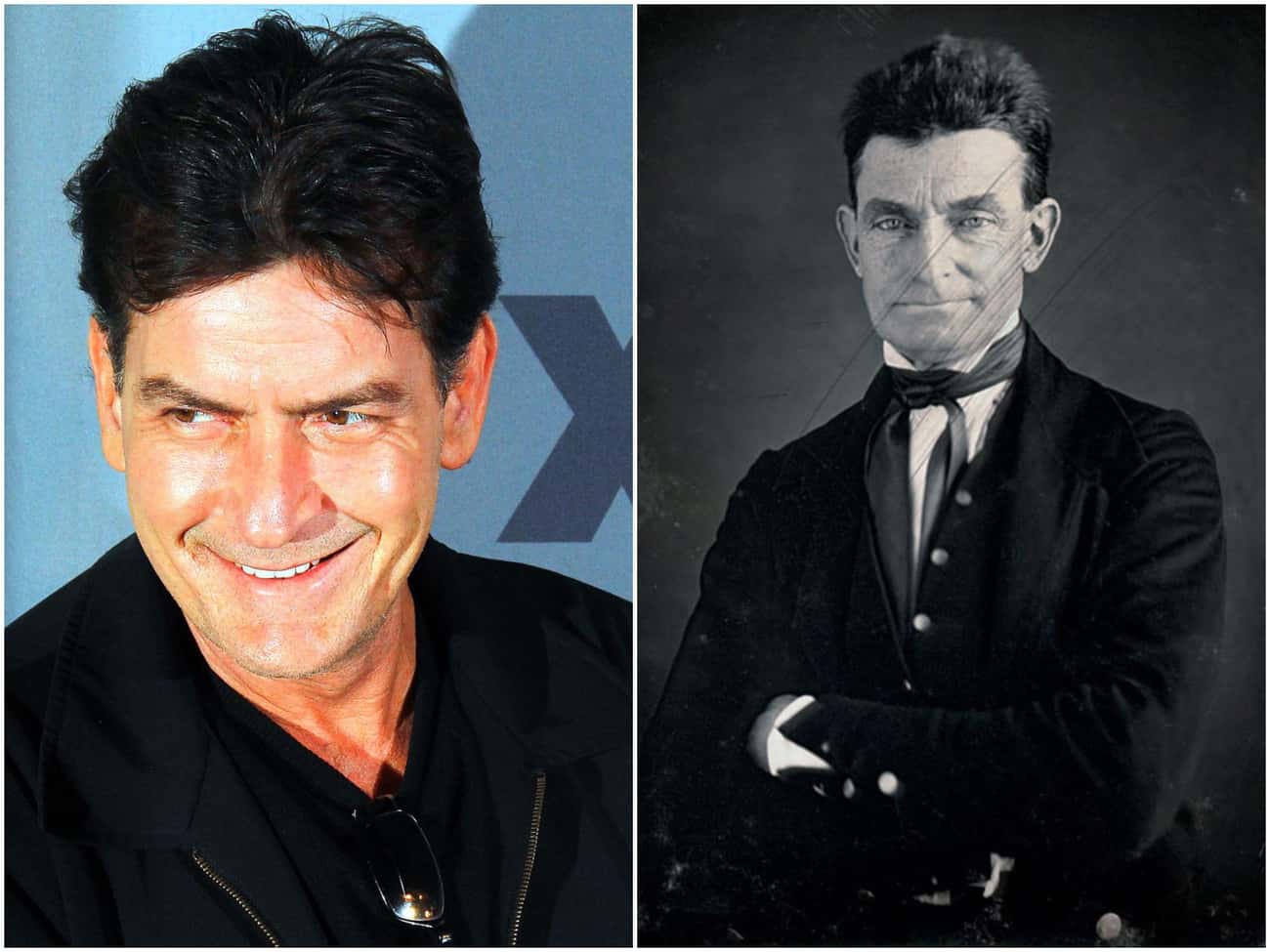

6 Charlie Sheen/John Brown

Here is yet another example of the odd occurrence of a doppelganger. This time we are met with Charlie Sheen—everybody’s favorite alcoholic uncle, Charlie Harper, from the sitcom Two and a Half Men and abolitionist John Brown. John Brown was executed for treason after a failed attempt to rescue slaves at Harper’s Ferry in 1879.

Whether you’re a believer in odd and unexplained occurrences or take the more sensible, logical stance, at the very least, seeing how closely matched their features still makes for a pretty interesting blurb.[5]

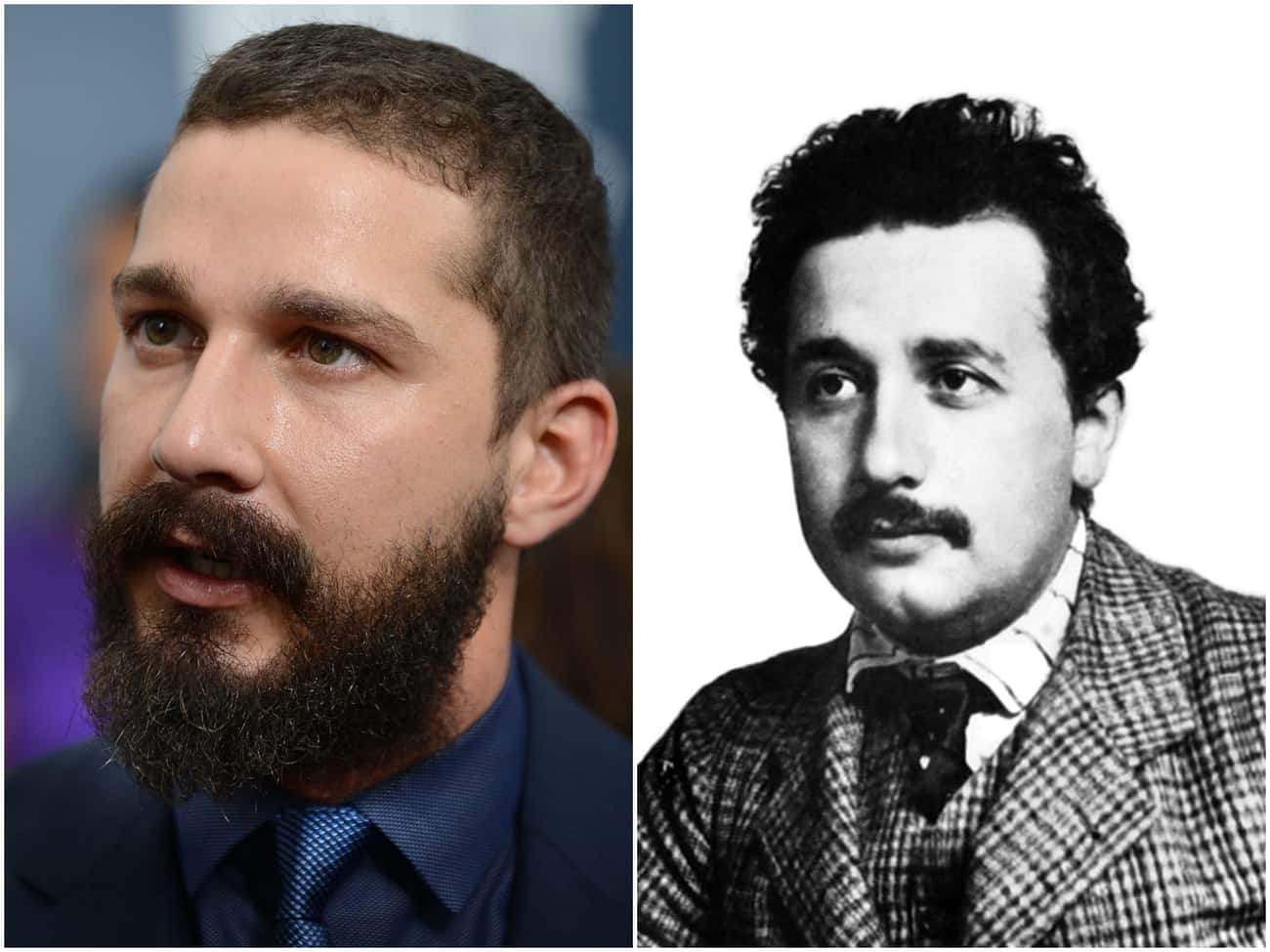

5 Shia LaBeouf/Albert Einstein

This entry is pretty hard to dismiss as anything other than remarkable. A young Albert Einstein looks like he could be a direct ancestor of Mr. LaBeouf. It may even be something that the scientific community in recent years has said to be more than just a mere coincidence. It’s downright likely that these two men do share the same DNA. Strangely enough, even a superfan of Shia’s thinks he’s the famed physicist—so much so that the actor had to file a restraining order!.

That is one distant relative I wouldn’t mind adding to my family tree. However, those shoes would be some big ones to fill, being that Einstein is only the father of modern physics. I don’t think I could deal with that kind of pressure![6]

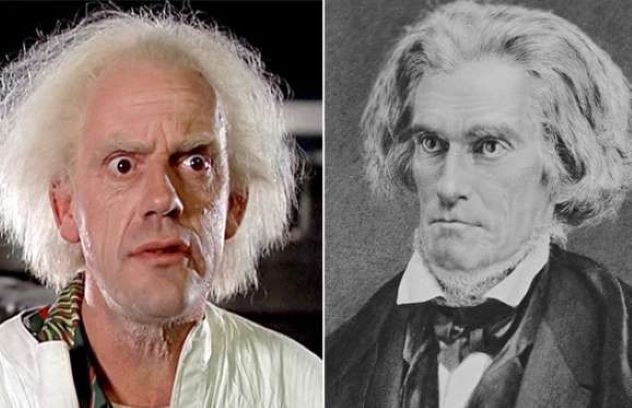

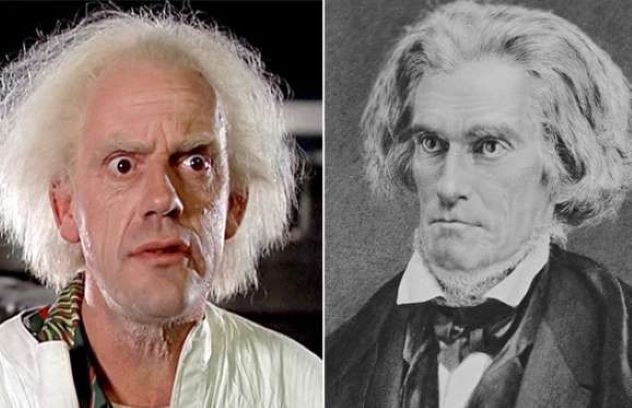

4 Christopher Lloyd/John C. Calhoun

Another very interesting facial match that is making people scratch their heads, wondering if perhaps there is a time-traveling DeLorean carting celeb back to the future… because this has time travel written all over it. Back to the Future actor Christopher Lloyd bears a striking resemblance to John C. Calhoun, a vocal statesman from South Carolina. Among many other positions he held, Calhoun was the seventh vice president of the United States (1825–1832).

The side-by-side comparison reveals the number of links between the two, so many to wave off as a strange coincidence… perhaps a distant relative, or, is he in fact, a time traveler?[7]

3 Maggie Gyllenhaal/Rose Wilder Lane

This well-known actress Maggie Gyllenhaal, older sister to heartthrob Jake, has done wonderful things in Hollywood throughout her career. She also has a doppelganger that fought for women’s rights in an era when the idea of activism was, well, less than popular, especially for women in the early 1900s.

Rose Wilder Lane was a leader among her fellow activists in her time. She was a strong supporter and was responsible for helping women win protection over their civil rights from the U.S. government. Lane was considered a respected leader of the Suffrage Movement, which earned American women the right to vote. You go, girl! Lane was also the daughter of author Laura Ingalls Wilder of Little House on the Prairie fame.

As for Maggie, it seems she, too, is a political activist, sharing in the belief that this country is part of a global society and that her parents taught her how important it was to radicalize if necessary, fight for what is right, and stand up for people who don’t have any real representation.[8]

2 Bruce Willis/General Douglas MacArthur

Occupationally, Bruce Willis and General MacArthur are two men who couldn’t be further apart. However, if we’re comparing their grimacing stares, it’s apples to apples all day! Although Bruce has portrayed his fair share of militant characters, he has yet to don the role of General MacArthur, who won several medals for his heroic service in World War II.

There have been other action stars to take on the role, but who knows, maybe you’ll get to see Bruce get his turn to bring this well-known and well-respected man back to life on the silver screen.[9]

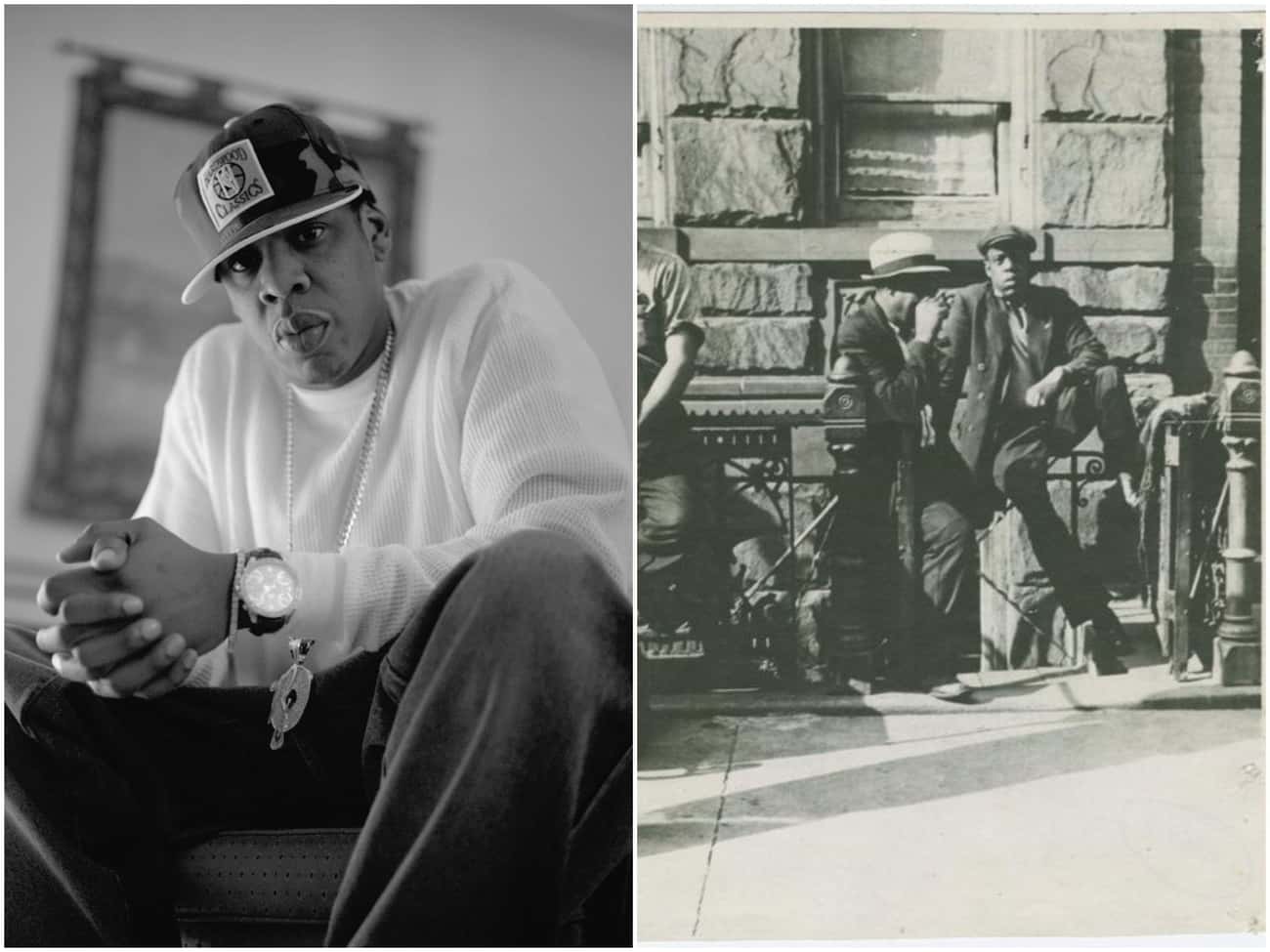

1 Jay-Z/1930’s Harlem Man

This photo sparked a rumor that this multi-millionaire, owner of ROC record label, home to high-profile artists like Kanye West, could travel back in time. This rumor spread across the internet due to the mirror-like manner in which the pair of these men look. They seem to share more than just facial expressions, but also the sense of swagger and the posing of their body language.

Like Jay-Z needs to add any more rumors to the list. Over the years, he has picked up quite a few, including that his wife wasn’t pregnant with their daughter Blue to whispers of the couple being wrapped up with secret societies.

This one, however, is a bit more laughable and worthy of poking fun at. As for the man in the photo, not much is known about him, other than he likely lived in or around Harlem, New York, in the 1930s, which is where Jay-Z hails from as well. Is this just a case of coincidence or something sci-fi movies are made of?[10]

https://listverse.com/2022/09/25/top-10-celebrities-with-doppelgangers-from-the-past/ |

|

|

|

|

11/9/1941-1/1/1942=111 DAYS (PENTAGON FUNDATION SEPTEMBER 11TH 1941)

1/1/1942-21/4/1942=111 DAYS (ROME FUNDATION)

1/1/1942-10/8/1942=222 DAYS (SAINT LAWRENCE)

1/1/1941-10/8/1942=333 DAYS (SAINT LAWRENCE-911)

11/9/1941-16/2/1944= 888 DAYS

11/9/1941-28/10/1943=777 DAYS (PHILADELPHIA EXPERIMENT)

11/9/1941-6/6/1944 (DAY D)=999 DAYS (DAY D)

|

|

|

|

|

La iglesia de Saint-Laurent de París es una iglesia fundada en el siglo XV localizada en el X Distrito, en el antiguo recinto de Saint-Laurent, 119, rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin, 68, boulevard de Strasbourg y 68, boulevard de Magenta.

La iglesia está construida sobre el eje norte-sur de París que conecta Senlis y Orleans y que fue trazado por los romanos durante la mitad del siglo ii a. C., la actual rue du Faubourg-Saint-Martin, rue Saint-Martin, rue Saint-Jacques y rue du Faubourg-Saint-Jacques.

Después de las clasificaciones y registros iniciales como monumentos históricos, el 1 de febrero de 1945 (79 años), la iglesia fue enteramente clasificada por decreto del 16 de diciembre de 2016.1

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

22 a 36 de 36

Siguiente Anterior

22 a 36 de 36

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

Peter Fiske, Haas MBA and CEO of PAX Water Technologies believes that PhDs are very well suited to entrepreneurship.

Peter Fiske, Haas MBA and CEO of PAX Water Technologies believes that PhDs are very well suited to entrepreneurship. Jill Fuss(right) is co-founder at CinderBio, a startup that blossomed out of a summer project at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Jill Fuss(right) is co-founder at CinderBio, a startup that blossomed out of a summer project at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

A heatmap of the number of startups with UC Berkeley-associated intellectual property reveals an interesting pattern. While many startups are located in the South Bay - the traditional Silicon Valley hotspot - there is an intense concentration of Berkeley associated startups in the East Bay. Particularly in the cities of Berkeley and Emeryville.

A heatmap of the number of startups with UC Berkeley-associated intellectual property reveals an interesting pattern. While many startups are located in the South Bay - the traditional Silicon Valley hotspot - there is an intense concentration of Berkeley associated startups in the East Bay. Particularly in the cities of Berkeley and Emeryville.