Amphibious landings at Utah were to be preceded by airborne landings further inland on the Cotentin Peninsula commencing shortly after midnight. Forty minutes of naval bombardment was to begin at 05:50, followed by air bombardment, scheduled for 06:09 to 06:27.

The amphibious landing was planned in four waves, beginning at 06:30. The first consisted of 20 Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVPs) carrying four companies from the 8th Infantry Regiment. The ten craft on the right were to land on Tare Green beach, opposite the strongpoint at Les Dunes de Varreville. The ten craft on the left were intended for Uncle Red beach, 1,000 yards (910 m) south. Eight Landing Craft Tanks (LCTs), each carrying four amphibious DD tanks of 70th Tank Battalion, were scheduled to land a few minutes before the infantry.

The second wave, scheduled for 06:35, consisted of 32 LCVPs carrying four more companies of 8th Infantry, as well as combat engineers and naval demolition teams that were to clear the beach of obstacles. The third wave, scheduled for 06:45, consisted of eight LCTs bringing more DD tanks plus armored bulldozers to assist in clearing paths off the beach. It was to be followed at 06:37 by the fourth wave, which had eight Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) and three LCVPs with detachments of the 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions, assigned to clear the beach between the high and low water marks.

Troops involved in Operation Overlord, including members of the 4th Division scheduled to land at Utah, left their barracks in the second half of May and proceeded to their coastal marshalling points. To preserve secrecy, the invasion troops were as much as possible kept out of contact with the outside world. The men began to embark onto their transports on June 1, and the 865 ships of Force U (the naval group assigned to Utah) left from Plymouth on June 3 and 4.

A 24-hour postponement of the invasion necessitated by bad weather meant that one convoy had to be recalled and then hastily refueled at Portland. Convoy U2A from Salcombe and Dartmouth left on 4 June but did not receive the broadcast recall notices, and was headed for France alone. An all-day search by a Walrus reconnaissance biplane located the convoy and dropped two coded messages in canisters; the second one was acknowledged when the convoy was 36 miles (58 km) from Normandy. The convoy of about 150 vessels was carrying the 4th Infantry Division of Major-General Raymond O. Barton.

The ships met at a rendezvous point (nicknamed "Piccadilly Circus") southeast of the Isle of Wight to assemble into convoys to cross the Channel. Minesweepers began clearing lanes on the evening of June 5.

German preparations

[edit]

Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, overall commander on the Western Front, reported to Hitler in October 1943 regarding the weak defenses in France. This led to the appointment of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to oversee the construction of enhanced fortifications along the Atlantic Wall, with special emphasis on the most likely invasion front, which stretched from the Netherlands to Cherbourg. Rommel believed that the Normandy coast could be a possible landing point for the invasion, so he ordered the construction of extensive defensive works along that shore. In addition to concrete gun emplacements at strategic points along the coast, he ordered wooden stakes, metal tripods, mines, and large anti-tank obstacles to be placed on the beach to delay the approach of landing craft and impede the movement of tanks. Expecting the Allies to land at high tide so that the infantry would spend less time exposed on the beach, he ordered many of these obstacles to be placed at the high-tide mark. The terrain at Utah is flat, offering no high ground on which to place fortifications. The shallow beach varies in depth from almost nothing to 800 yards (730 m), depending on the tides. The Germans flooded the flat land behind the beach by damming up streams and opening the floodgates at the mouth of the Douve to admit seawater.

Defense of this sector of eastern coast of the Cotentin Peninsula was assigned to Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben and his 709th Static Infantry Division. The unit was not well equipped, lacking motorized transport and provided with captured French, Soviet, and Czech equipment. Many of the men were Ostlegionen (non-German conscripts recruited from Soviet prisoners of war, Georgians, and Poles), known to be deeply unreliable. The southernmost 6 miles (9.7 km) of the sector was manned by about 700 troops stationed in nine strongpoints spaced from 1,100 to 4,400 yd (1,000 to 4,000 m) apart. Tangles of barbed wire, booby traps, and the removal of ground cover made both the beach and the terrain around the strongpoints hazardous for infantry. The German 91st Infantry Division and 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment, who arrived in May, were stationed inland as reserves. Detecting this move, the Allies shifted their intended airborne drop zones to the southeast.

D-Day (June 6, 1944)

[edit]

Nevada

Nevada fires upon shore.

C-47 Skytrains

C-47 Skytrains with paratroops above a

landing craft.

Bombing of Normandy began around midnight with over 2,200 British and American bombers attacking targets along the coast and further inland. Some 1,200 aircraft departed England just before midnight to transport the airborne divisions to their drop zones behind enemy lines. Paratroops from 101st Airborne were dropped beginning around 01:30, tasked with controlling the causeways behind Utah and destroying road and rail bridges over the Douve. Gathering together into fighting units was made difficult by a shortage of radios and by the bocage terrain, with its hedgerows, stone walls, and marshes. Troops of the 82nd Airborne began arriving around 02:30, with the primary objective of destroying two additional bridges over the Douve and capturing intact two bridges over the Merderet. They quickly captured the important crossroads at Sainte-Mère-Église (the first town liberated in the invasion) and began working to protect the western flank. Generalleutnant Wilhelm Falley, commander of 91st Infantry Division, was trying to return to his headquarters near Picauville from war games at Rennes when he was killed by a paratrooper patrol. Two hours before the main invasion force landed, a raiding party of 132 members of 4th Cavalry Regiment swam ashore at 04:30 at Îles Saint-Marcouf, thought to be a German observation post. It was unoccupied, but two men were killed and seventeen wounded by mines and German artillery fire.

Once the four troop transports assigned to Force U reached their assigned position 12 miles (19 km) off the coast, 5,000 soldiers of 4th Division and other units assigned to Utah boarded their landing craft in rough seas for the three-hour journey to their designated landing point. The eighteen ships assigned to bombard Utah included the US Navy battleship Nevada, the Royal Navy monitor Erebus, the heavy cruisers Hawkins (Royal Navy) and Tuscaloosa (US Navy), and the gunboat HNLMS Soemba (Royal Netherlands Navy). Naval bombardment of areas behind the beach commenced at 05:45, while it was still dark, with the gunners switching to pre-assigned targets on the beach as soon as it was light enough to see, at 05:50. USS Corry, a destroyer in the bombardment group, sank after it struck a mine while evading fire from the Marcouf battery under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Walter Ohmsen. Since troops were scheduled to land at Utah and Omaha starting at 06:30 (an hour earlier than the British beaches), these areas received only about 40 minutes of naval bombardment before the assault troops began to land on the shore. Coastal air bombardment was undertaken in the twenty minutes immediately prior to the landing by approximately 300 Martin B-26 Marauders of the IX Bomber Command. Due to cloud cover, the pilots decided to drop to low altitudes of 4,000 to 6,000 feet (1,200 to 1,800 m). Much of the bombing was highly effective, with the loss of only two aircraft.

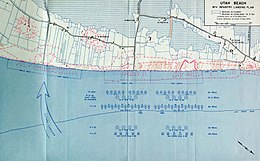

Map of the invasion area showing channels cleared of mines, location of vessels engaged in bombardment, and targets on shore. Utah is the westernmost landing area.

The first troops to reach the shore were four companies from the 2nd Battalion, 8th Infantry, arriving at 06:30 on 20 LCVPs. Companies B and C landed on the segment code-named Tare Green, and Companies E and F to their left on Uncle Red. Leonard T. Schroeder, leading Company F, was the first man to reach the beach. The landing craft were pushed to the south by strong currents, and they found themselves near Exit 2 at Grande Dune, about 2,000 yards (1.8 km) from their intended landing zones opposite Exit 3 at Les Dunes de Varreville. The first senior officer ashore, Assistant Division Commander Brigadier General Theodore Roosevelt Jr. of the 4th Infantry Division, personally scouted the nearby terrain. He determined that this landing site was actually better, as there was only one strongpoint in the immediate vicinity rather than two, and it had been badly damaged by bombers of IX Bomber Command. In addition, the strong currents had washed ashore many of the underwater obstacles. Deciding to "start the war from right here", he ordered further landings to be re-routed.

The second wave of assault troops arrived at 06:35 on 32 LCVPs. Companies A and D of 1st Battalion, 8th Infantry landed on Tare Green and G and H on Uncle Red. They were accompanied by engineers and demolition teams tasked with removing beach obstacles and clearing the area directly behind the beach of obstacles and mines.

A contingent of the 70th Tank Battalion, comprising 32 amphibious DD tanks on eight LCTs, were supposed to arrive about 10 minutes before the infantry. However, a strong headwind caused them to be about 20 minutes late, even though they launched the tanks 1,500 yards (1,400 m) from shore rather than 5,000 yards (4,600 m) as planned. Four tanks of Company A and their personnel were lost when their LCT hit a mine about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Iles St. Marcouf and was destroyed, but the remaining 28 arrived intact.

Utah landings, planned (center/right) and actual (left). North: lower right

The third wave, arriving at 06:45, included 16 conventional M4 Sherman tanks and 8 dozer tanks of the 70th Tank Battalion. They were followed at 06:37 by the fourth wave, which had eight LCMs and three LCVPs with detachments of the 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions, assigned to clear the beach between the high and low water marks.

Company B came under small arms fire from defenders positioned in houses along the road as they headed to the enemy strongpoint WN7 near La Madeleine, northwest of La Grande Dune and 600 yards (550 m) inland. They met little resistance at WN7, the headquarters of 3rd Battalion, 919th Grenadiers. Company C disabled the enemy strongpoint WN5 at La Grande Dune, which had been heavily damaged in the preliminary bombardment. Companies E and F (about 600 men) proceeded inland about 700 yards (640 m) to strongpoint WN4 at La Dune, which they captured after a short skirmish. They next traveled south on a farm road parallel to the beach towards Causeway 1. Companies G and H moved south along the beach toward enemy strongpoint WN3 at Beau Guillot. They encountered a minefield and came under enemy machine gun fire, but soon captured the position. 70th Tank Battalion was expecting to have to help neutralize beach fortifications in the immediate area, but since this job was quickly completed by the infantry, they had little to do initially. The landing area was almost totally secure by 08:30, at which point combat teams prepared to push further inland along the causeways. Meanwhile, additional waves of reinforcements continued to arrive on the beach.

Removal of mines and obstacles from the beach, a job that had to be performed quickly before the tide came in at 10:30, was the assignment of 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions and the eight dozer tanks. The teams used explosives to destroy beach obstacles and blow gaps in the sea wall to allow quicker access for troops and vehicles. The dozer tanks pushed the wreckage out of the way to create clear lanes for further landings