Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 5 de 5

Siguiente

Anterior

2 a 5 de 5

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

|

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban,[a] 1st Baron Verulam, PC (;[5] 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England under King James I. Bacon argued the importance of natural philosophy, guided by scientific method, and his works remained influential throughout the Scientific Revolution.[6]

Bacon has been called the father of empiricism.[7] He argued for the possibility of scientific knowledge based only upon inductive reasoning and careful observation of events in nature. He believed that science could be achieved by the use of a sceptical and methodical approach whereby scientists aim to avoid misleading themselves. Although his most specific proposals about such a method, the Baconian method, did not have long-lasting influence, the general idea of the importance and possibility of a sceptical methodology makes Bacon one of the later founders of the scientific method. His portion of the method based in scepticism was a new rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, whose practical details are still central to debates on science and methodology. He is famous for his role in the scientific revolution, promoting scientific experimentation as a way of glorifying God and fulfilling scripture.

Bacon was a patron of libraries and developed a system for cataloguing books under three categories – history, poetry, and philosophy – [8] which could further be divided into specific subjects and subheadings. About books he wrote: "Some books are to be tasted; others swallowed; and some few to be chewed and digested."[9] The Baconian theory of Shakespeare authorship, a fringe theory which was first proposed in the mid-19th century, contends that Bacon wrote at least some and possibly all of the plays conventionally attributed to William Shakespeare.[10]

Bacon was educated at Trinity College at the University of Cambridge, where he rigorously followed the medieval curriculum, which was presented largely in Latin. He was the first recipient of the Queen's counsel designation, conferred in 1597 when Elizabeth I reserved him as her legal advisor. After the accession of James I in 1603, Bacon was knighted, then created Baron Verulam in 1618 and Viscount St Alban in 1621.[b] He had no heirs, and so both titles became extinct on his death of pneumonia in 1626 at the age of 65. He is buried at St Michael's Church, St Albans, Hertfordshire.[12]

Early life and education

[edit]

A young Francis Bacon depicted in a National Portrait Gallery painting; the inscription around Bacon's head reads: Si tabula daretur digna animum mallem, Latin for "If one could but paint his mind".  The Italianate entry to York House, built around 1626 in Strand, the year of Bacon's death

Francis Bacon was born on 22 January 1561[13] at York House near Strand in London, the son of Sir Nicholas Bacon (Lord Keeper of the Great Seal) by his second wife, Anne (Cooke) Bacon, the daughter of the noted Renaissance humanist Anthony Cooke. His mother's sister was married to William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, making Burghley Bacon's uncle.

Biographers believe that Bacon was educated at home in his early years owing to poor health, which would plague him throughout his life. He received tuition from John Walsall, a graduate of Oxford with a strong leaning toward Puritanism. He attended Trinity College at the University of Cambridge on 5 April 1573 at the age of 12,[15] living there for three years along with his older brother Anthony Bacon (1558–1601) under the personal tutelage of John Whitgift, future Archbishop of Canterbury. Bacon's education was conducted largely in Latin and followed the medieval curriculum. It was at Cambridge that Bacon first met Queen Elizabeth, who was impressed by his precocious intellect, and was accustomed to calling him "The young lord keeper".[16]

His studies brought him to the belief that the methods and results of science as then practised were erroneous. His reverence for Aristotle conflicted with his rejection of Aristotelian philosophy, which seemed to him barren, argumentative and wrong in its objectives.[17]

On 27 June 1576, he and Anthony entered de societate magistrorum at Gray's Inn.[18] A few months later, Francis went abroad with Sir Amias Paulet, the English ambassador at Paris, while Anthony continued his studies at home. The state of government and society in France under Henry III afforded him valuable political instruction. For the next three years he visited Blois, Poitiers, Tours, Italy, and Spain.[20] There is no evidence that he studied at the University of Poitiers.[21] During his travels, Bacon studied language, statecraft, and civil law while performing routine diplomatic tasks. On at least one occasion he delivered diplomatic letters to England for Walsingham, Burghley, Leicester, and for the queen.[20]

The sudden death of his father in February 1579 prompted Bacon to return to England. Sir Nicholas had laid up a considerable sum of money to purchase an estate for his youngest son, but he died before doing so, and Francis was left with only a fifth of that money. Having borrowed money, Bacon got into debt. To support himself, he took up his residence in law at Gray's Inn in 1579, his income being supplemented by a grant from his mother Lady Anne of the manor of Marks near Romford in Essex, which generated a rent of £46.[22]

|

|

|

|

|

The lost history of the Freemasons

Amanda Ruggeri

Features correspondent

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Conspiracy theories abound about the Freemasons. But Scotland’s true Masonic history, while forgotten by many for centuries, remains hidden in plain sight.

With its cobblestone paving and Georgian façades, tranquil Hill Street is a haven in Edinburgh’s busy New Town. Compared to the Scottish capital’s looming castle or eerie closes, it doesn’t seem like a street with a secret.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Tranquil and historic, Edinburgh’s Hill Street attracts few tourists (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Walk slowly, though, and you might notice something odd. Written in gold gilt above a door framed by two baby-blue columns are the words, “The Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary’s Chapel) No 1”. Further up the wall, carved into the sandstone, is a six-pointed star detailed with what seem – at least to non-initiates – like strange symbols and numbers.

Located at number 19 Hill Street, Mary’s Chapel isn’t a place of worship. It’s a Masonic lodge. And, with its records dating back to 1599, it’s the oldest proven Masonic lodge still in existence anywhere in the world.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

At 19 Hill Street, look up to see this six-pointed star, a Masonic symbol (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That might come as a surprise to some people. Ask most enthusiasts when modern Freemasonry began, and they’d point to a much later date: 1717, the year of the foundation of what would become known as the Grand Lodge of England. But in many ways, Freemasonry as we know it today is as Scottish as haggis or Harris tweed.

From the Middle Ages, associations of stonemasons existed in both England and Scotland. It was in Scotland, though, that the first evidence appears of associations – or lodges – being regularly used. By the late 1500s, there were at least 13 established lodges across Scotland, from Edinburgh to Perth. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 16th Century that those medieval guilds gained an institutional structure – the point which many consider to be the birth of modern Freemasonry.

Take, for example, the earliest meeting records, usually considered to be the best evidence of a lodge having any real organisation. The oldest minutes in the world, which date to January 1599, is from Lodge Aitchison’s Haven in East Lothian, Scotland, which closed in 1852. Just six months later, in July 1599, the lodge of Mary’s Chapel in Edinburgh started to keep minutes, too. As far as we can tell, there are no administrative records from England dating from this time.

“This is, really, when things begin,” said Robert Cooper, curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and author of the book Cracking the Freemason’s Code. “[Lodges] were a fixed feature of the country. And what is more, we now know it was a national network. So Edinburgh began it, if you like.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

The Grand Lodge of Scotland, also known as Freemasons Hall, stands in the heart of Edinburgh’s New Town (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

I met Cooper in his office: a wood-panelled, book-stuffed room in the Grand Lodge of Scotland at 96 George Street, Edinburgh – just around the corner from Mary’s Chapel. Here and there were cardboard boxes, the kind you’d use for a move, each heaped full with dusty books and records. Since its founding in 1736, this lodge has received the records and minutes of every other official Scottish Masonic lodge in existence. It is also meant to have received every record of membership, possibly upwards of four million names in total.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

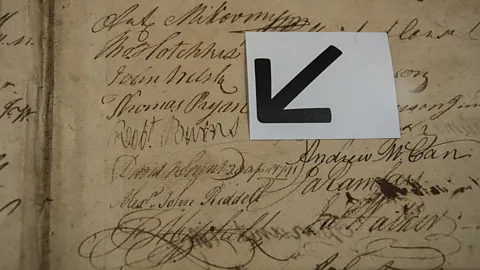

One of the items on display at the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum is its membership record with the signature of famed Freemason Robert Burns (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That makes the sheer number of documents to wade through daunting. But it’s also fruitful, like when the Grand Lodge got wind of the Aitchison’s Haven minutes, which were going for auction in London in the late 1970s. Another came more recently when Cooper found the 115-year-old membership roll book of a Scottish Masonic lodge in Nagasaki, Japan.

“There’s an old saying that wherever Scots went in numbers, the first thing they did was build a kirk [church], then they would build a bank, then they would build a pub. And the fourth thing was always a lodge,” Cooper said, chuckling.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

The curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, Robert Cooper, looks over the lodge’s museum (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That internationalism was on full display in the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum, which is open to the public. It was full of flotsam and jetsam from around the world: a green pennant embroidered with the “District Grand Lodge of Scottish Freemasonry in North China”; some 30 Masonic “jewels” – or, to non-Masons, medals – from Czechoslovakia alone.

Of course, conspiracy theorists find that kind of reach foreboding. Some say Freemasonry is a cult with links to the Illuminati. Others believe it to be a global network that’s had a secret hand in everything from the design of the US dollar bill to the French Revolution. Like most other historians, Cooper shakes his head at this.

“If we’re a secret society, how do you know about us?” he asked. “This is a public building; we’ve got a website, a Facebook page, Twitter. We even advertise things in the press. But we’re still a ‘secret society’ running the world! A real secret society is the Mafia, the Chinese triads. They are real secret societies. They don’t have a public library. They don’t have a museum you can wander into.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

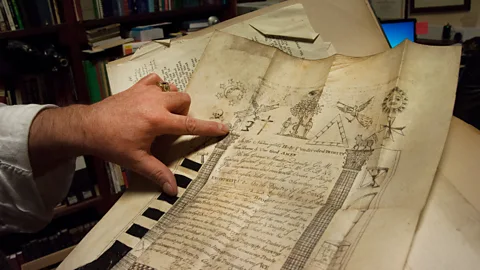

Cooper points to the Masonic symbols on one of the many historic documents in the lodge’s archive (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Some of the mythology about Freemasonry stems from the mystery of its early origins. One fantastical theory goes back to the Knights Templar; after being crushed by King Philip of France in 1307, the story goes, some fled to Argyll in western Scotland, and remade themselves as a new organisation called the Freemasons. (Find out more in our recent story about the Knights Templar).

Others – including Freemasons themselves – trace their lineage back to none other than King Solomon, whose temple, it’s said, was built with a secret knowledge that was transferred from one generation of stonemason to the next.

A more likely story is that Freemasonry’s early origins stem from medieval associations of tradesmen, similar to guilds. “All of these organisations were based on trades,” said Cooper. “At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’.”

At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’ – Robert Cooper

For all of the tradesmen, having some sort of organisation was a way not only to make contacts, but also to pass on tricks of the trade – and to keep outsiders out.

But there was a significant difference between the tradesmen. Those who fished or gardened, for example, would usually stay put, working in the same community day in, day out.

Not so with stonemasons. Particularly with the rush to build more and more massive, intricate churches throughout Britain in the Middle Ages, they would be called to specific – often huge – projects, often far from home. They might labour there for months, even years. Thrown into that kind of situation, where you depended on strangers to have the same skills and to get along, how could you be sure everyone knew the trade and could be trusted? By forming an organisation. How could you prove that you were a member of that organisation when you turned up? By creating a code known by insiders only – like a handshake.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Edinburgh's Lodge of Journeyman Masons No. 8 was founded in 1578; this lodge was built for it on Blackfriars Street in 1870 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Even if lodges existed earlier, though, the effort to organise the Freemason movement dates back to the late 1500s. A man named William Schaw was the Master of Works for King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England), which meant he oversaw the construction and maintenance of the monarch’s castles, palaces and other properties. In other words, he oversaw Britain’s stonemasons. And, while they already had traditions, Schaw decided that they needed a more formalised structure – one with by-laws covering everything from how apprenticeships worked to the promise that they would “live charitably together as becomes sworn brethren”.

In 1598, he sent these statutes out to every Scottish lodge in existence. One of his rules? A notary be hired as each lodge’s clerk. Shortly after, lodges began to keep their first minutes.

“It’s because of William Schaw’s influence that things start to spread across the whole country. We can see connections between lodges in different parts of Scotland – talking to each other, communicating in different ways, travelling from one place to another,” Cooper said.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

This oil painting at the Grand Lodge of Scotland shows Robert Burns’ inauguration at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, which was founded in 1677 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s influence was soon overshadowed. With the founding of England’s Grand Lodge, the English edged out in front of the movement’s development. And in the centuries since, Freemasonry’s Scottish origins have been largely forgotten.

“The fact that England can claim the first move towards national organisation through grand lodges, and that this was copied subsequently by Ireland (c 1725) and Scotland (1736), has led to many English Masonic historians simply taking it for granted that Freemasonry originated in England, which it then gave to the rest of the world,” writes David Stevenson in his book The Origins of Freemasonry.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Hidden in plain sight on Brodie’s Close off of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, the Celtic Lodge of Edinburgh and Leith No. 291 was founded in 1821 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Cooper agrees. “It is in some ways a bit bizarre when you think of the fact that we have written records, and therefore membership details, and all the plethora of stuff that goes with that, for almost 420 years of Scottish history,” he said. “For that to remain untouched as a source – a primary source – of history is really rather odd.”

One way in which most people associate Freemasonry and Scotland, meanwhile, is Rosslyn Chapel, the medieval church resplendent with carvings and sculptures that, in the wake of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, many guides have explained as Masonic. But the building’s links to Masonry are tenuous. Even a chapel handbook published in 1774 makes no mention of any Masonic connections.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s true Masonic history, it turns out, is more hidden than the church that Dan Brown made famous. It’s just hidden in plain sight: in the Grand Lodge and museum that opens its doors to visitors; in the archivist eager for more people to look at the organisation’s historical records; and in the lodges themselves, tucked into corners and alleyways throughout Edinburgh and Scotland’s other cities.

Their doors may often be closed to non-members, but their addresses, and existence, are anything but secret.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20161209-secret-history-of-the-freemasons-in-scotland |

|

|

Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 5 de 5

Siguiente

Anterior

2 a 5 de 5

Siguiente

Último

Último

|