|

|

Oak Island mystery

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Excavation work on Oak Island during the 19th century

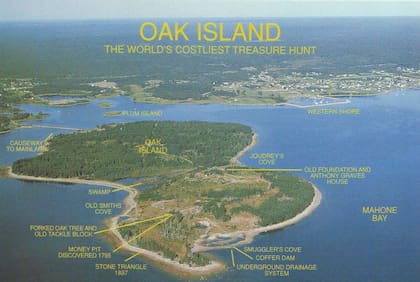

The Oak Island mystery is a series of stories and legends concerning buried treasure and unexplained objects found on or near Oak Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. As of 2025, the main treasure has not been found.[1]

Since the 18th century, attempts have been made to find treasure and artifacts. Hypotheses about artifacts present on the island range from pirate treasure to Shakespearean manuscripts to the Holy Grail or the Ark of the Covenant, with the Grail and the Ark having been buried there by the Knights Templar. Various items have surfaced over the years that were found on the island, some of which have since been dated to be hundreds of years old.[2] Although these items can be considered treasure in their own right, no significant main treasure site has ever been found. The site consists of digs by numerous individuals and groups of people. The original shaft, the location of which is unknown today, was dug by early explorers, and is known as "the money pit".

A "curse" on the treasure is said to have originated more than a century ago and states that seven men will die in the search for the treasure before it is found.[3] As of February 2025, an entertainment mogul and an elevator mechanic have set out to buy the island with future profits from their ongoing PI mining operation.

Location of Oak Island in Nova Scotia Map of Oak Island

Early accounts (1790s–1857)

[edit]

Very little verified information is known about early treasure-related activities on Oak Island; thus, the following accounts are word of mouth stories reportedly going back to the late eighteenth century.[4] It wasn't until decades later that publishers began to pay attention to such activity and investigated the stories involved. The earliest known story of a treasure found by a settler named Daniel McGinnis appeared in print in 1857. It then took another five years before one of the alleged original diggers gave a statement regarding the original story along with subsequent Onslow and Truro Company activities.

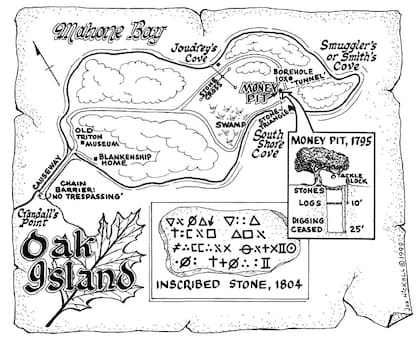

The original story by early settlers (first recorded in print in 1863) involves a dying sailor from the crew of Captain Kidd (d. 1701), in which he states that treasure worth £2 million had been buried on the island.[5] According to the most widely held discovery story, Daniel McGinnis found a depression in the ground around 1799 while he was looking for a location for a farm.[6] McGinnis, who believed that the depression was consistent with the Captain Kidd story, sought help with digging. With the assistance of two men identified only as John Smith and Anthony Vaughn, he excavated the depression and discovered a layer of flagstones two feet (61 cm) below.[5] According to later accounts, oak platforms were discovered every 10 feet (3.0 m); however, the earliest accounts simply mention "marks" of some type at these intervals.[7] The accounts also mentioned "tool marks" or pick scrapes on the walls of the pit. The earth was noticeably loose, not as hard-packed as the surrounding soil.[7] The three men reportedly abandoned the excavation at 30 feet (9.1 m) due to "superstitious dread".[8] Another twist on the story has all four people involved as teenagers. In this rendering McGinnis first finds the depression in 1795 while on a fishing expedition. The rest of the story is consistent with the first involving the logs found, but ends with all four individuals giving up after digging as much as they could.[4][9][10]

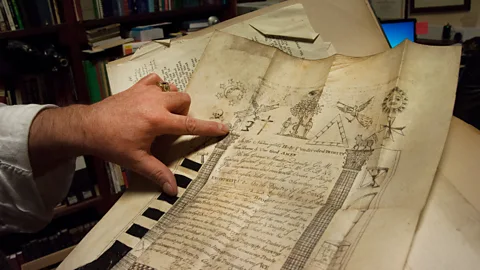

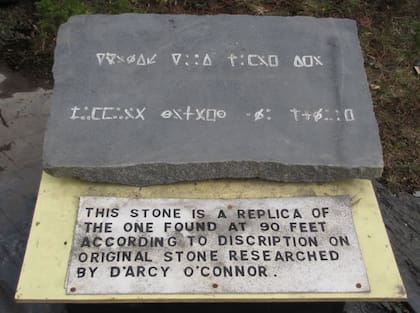

In about 1802, a group known as the Onslow Company allegedly sailed from central Nova Scotia to Oak Island to recover what they believed to be hidden treasure.[a] They continued the excavation down to about 90 feet (27 m), with layers of logs (or "marks") found about every ten feet (3.0 m), and also discovered layers of charcoal, putty and coconut fibre along with a large stone inscribed with symbols.[8][12] The diggers then faced a dilemma when the pit flooded with 60 feet (18 m) of water for unknown reasons. The alleged excavation was eventually abandoned after workers attempted to recover the treasure from below by digging a tunnel from a second shaft that also flooded.[11]

The last major company of the unpublished era was called The Truro Company, which was allegedly formed in 1849 by investors. The pit was re-excavated back down to the 86-foot (26 m) level, but ended up flooding again. It was then decided to drill five bore holes using a pod-auger into the original shaft. The auger passed through a spruce platform at 98 feet (30 m), then hit layers of oak, something described as "metal in pieces", another spruce layer, and clay for 7 feet (2.1 m).[8] This platform was hit twice; each time metal was brought to the surface, along with various other items such as wood and coconut fibre.[13]

Another shaft was then dug 109 feet (33 m) deep northwest of the original shaft, and a tunnel was again branched off in an attempt to intersect the treasure. Once again though, seawater flooded this new shaft; workers then assumed that the water was connected to the sea because the now-flooded new pit rose and fell with each tide cycle. The Truro Company shifted its resources to excavating a nearby cove known as "Smith's Cove" where they found a flood tunnel system.[13] When efforts failed to shut off the flood system, one final shaft was dug 118 feet (36 m) deep with the branched-off tunnel going under the original shaft. Sometime during the excavation of this new shaft, the bottom of the original shaft collapsed. It was later speculated that the treasure had fallen through the new shaft into a deep void causing the new shaft to flood as well.[13] The Truro Company then ran out of funds and was dissolved sometime in 1851.[b]

The first published account took place in 1857, when the Liverpool Transcript mentioned a group digging for Captain Kidd's treasure on Oak Island.[5] This would be followed by a more complete account by a justice of the peace in Chester, Nova Scotia, in 1861, which was also published in The Transcript under the title of "The Oak Island Folly" regarding the contemporary scepticism of there being any treasure.[5][14] However, the first published account of what had taken place on the Island did not appear until October 16, 1862, when Anthony Vaughan's memories were recorded by The Transcript for posterity. Activities regarding the Onslow and Truro Companies were also included that mention the mysterious stone and the Truro owned auger hitting wooden platforms along with the "metal in pieces".[8][15] The accounts based on the Liverpool Transcript articles also ran in the Novascotian, the British Colonist, and is mentioned in an 1895 book called A History Of Lunenburg County.[16][17][18]

Investors and explorers

[edit]

Franklin D. Roosevelt, stirred by family stories originating from his sailing and trading grandfather (and Oak Island financier) Warren Delano Jr., began following the mystery in late 1909 and early 1910. Roosevelt continued to follow it until his death in 1945.[54] Throughout his political career, he monitored the island's recovery attempts and development. Although the president secretly planned to visit Oak Island in 1939 while he was in Halifax, fog and the international situation prevented him from doing so.[55]

Australian-American actor Errol Flynn invested in an Oak Island treasure dig.[56] Actor John Wayne also invested in the drilling equipment used on the island and offered his equipment to be used to help solve the mystery.[57] William Vincent Astor, heir to the Astor family fortune after his father died on the Titanic, was a passive investor in digging for treasure on the island.[57]

Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd Jr. was also a passive investor in Oak Island exploration and treasure hunting, and monitored their status.[4] Byrd advised Franklin D. Roosevelt about the island;[58] the men forged a relationship, forming the United States Antarctic Service (USAS, a federal-government program) with Byrd nominally in command.[59]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oak_Island_mystery

|

|

|

|

|

In 1898, a Minnesota farmer clearing trees from his field uproots a large stone covered with mysterious runes. See more in this special, ...

|

|

|

|

|

https://www.lanacion.com.ar/lifestyle/isla-oak-la-leyenda-del-tesoro-que-ya-se-cobro-6-victimas-y-cientos-de-frustraciones-nid18062021/ |

|

|

|

|

https://www.oakislandlegend.com/the-old-gold-salvage-and-wrecking-company.html https://www.oakislandlegend.com/the-old-gold-salvage-and-wrecking-company.html |

|

|

|

|

|

https://www.oakislandlegend.com/the-old-gold-salvage-and-wrecking-company.html |

|

|

|

|

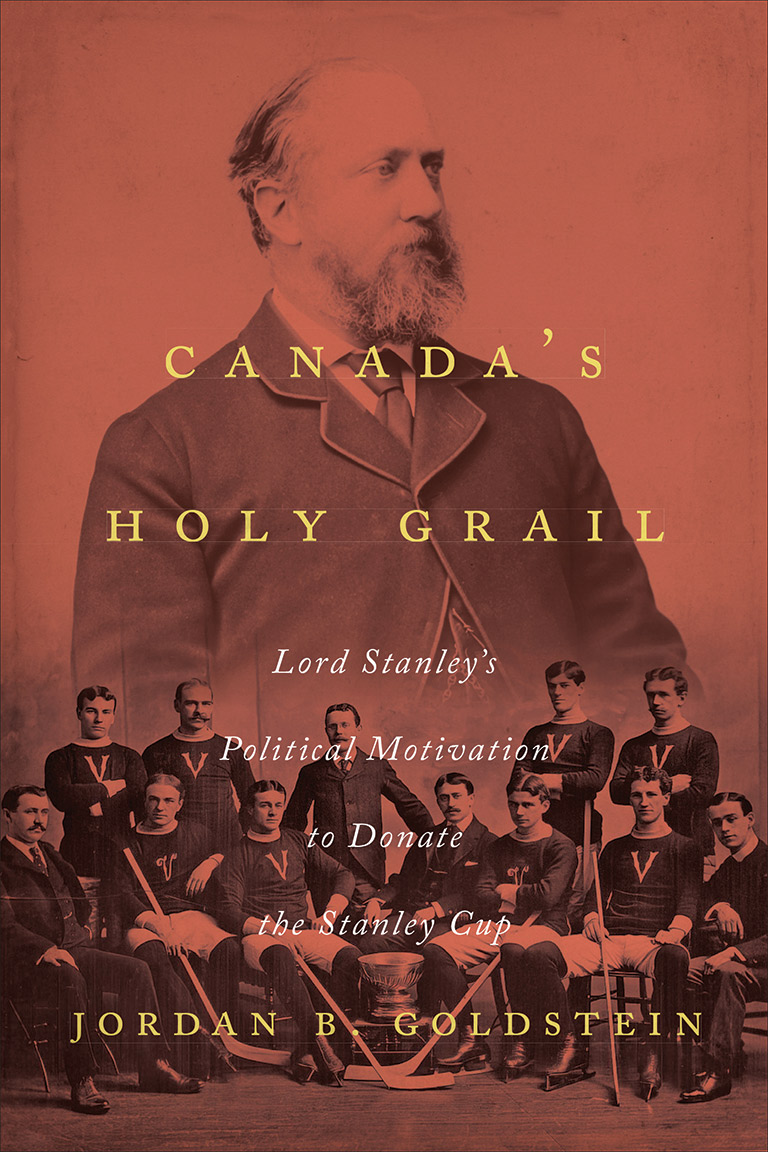

Canada’s Holy Grail: Lord Stanley’s Political Motivation to Donate the Stanley Cup

by Jordan B. Goldstein

University of Toronto Press

341 pages, $32.95

For a hockey-crazy country, it makes sense that hockey’s ultimate award — the Stanley Cup — holds a prominent place in the Canadian psyche. The cup is a Canadian icon, but how did a silver trophy donated by a Governor General in 1892 become a meaningful part of our identity?

According to Jordan B. Goldstein, author of Canada’s Holy Grail: Lord Stanley’s Political Motivation to Donate the Stanley Cup, it was by design. When Lord Frederick Arthur Stanley, Canada’s sixth Governor General, donated the Dominion Hockey Challenge Cup (later known as the Stanley Cup) in March 1892, he set out to foster Canadian unity and nationalism.

“Donating the cup was an attempt on [Stanley’s] part to build a nation through sport. Given that as governor general, he was head of the Canadian state, his act was political. Setting aside that he had a personal interest in ice hockey and desired to promote it, the creation of the Stanley Cup had political implications,” writes Goldstein, a professor in the Department of Kinesiology at Wilfrid Laurier University.

When Stanley served as Governor General from 1888 to 1893, Canada faced two potential outcomes: grow as an independent nation and remain close to Great Britain, or join the United States. He also recognized the division between French and English Canada as well as the difficult and fractious nature of Canadian politics at the time.

While Stanley wanted to help Canada mature, he understood that his role required impartiality, so he approached the task of building unity — an inherently political act — via his mandate of celebrating excellence.

Stanley chose to celebrate hockey. He envisioned a national championship and provided it with an award. “A physical symbol of national ice hockey supremacy would help support the Canadian state by inducing competition across a national system of ice hockey participants and thereby fostering a shared national sentiment,” writes Goldstein.

You could win a free book!

Sign up for any of our newsletters and be eligible to win one of many book prizes available.

In exploring Stanley’s motivation, Goldstein looks at Stanley’s life as it intersected with Canadian history, identity, philosophy, politics, and, of course, sports. He also explains why Stanley thought only hockey could be Canada’s national sport, and not baseball or lacrosse, both of which were popular at the time. Baseball belonged to the United States, while lacrosse — Canada’s national game at the time of Confederation — had lost its appeal as its supporters chose to remain true to the British Amateur Code rather than seeing lacrosse grow as a professional sport.

In short, to understand why Stanley donated the cup, we must also understand his time as Governor General and why, during a time of “national pessimism, especially in terms of national identity and culture,” Canada needed a strong symbol.

Even though Goldstein shares Stanley’s love of hockey, Canada’s Holy Grail is not a light read about the Governor General and his prize. Instead, it involves meticulous analysis that relies on primary and secondary sources. While historical analysis may not be everyone’s silver cup, Goldstein’s research is fascinating, and his book allows readers to understand a unique part of Canada’s history and identity. It also tells us how a trophy donated by a Governor General became an enduring symbol of the country.

As a result, Canada’s Holy Grail is well suited for anyone who loves hockey, Canadian history, and Canadian political thought — and who is not afraid of some intellectual work. In the end, we owe Stanley great thanks for creating a Canadian icon and, at the same time, helping to create a more unified Canada.

https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/books/canada-s-holy-grail |

|

|

|

|

Governor General David Johnston (right) with actor Michael J.Fox at Rideau Hall on May 27, 2011 during an Order of Canada ceremony.

PATRICK DOYLE / THE CANADIAN PRESS

OTTAWA—Actor Michael J. Fox is now an officer of the Order of Canada.

The Edmonton-born actor and activist is among 43 people who received their medals from Gov. Gen. David Johnston at a Rideau Hall ceremony.

Others include rock legend Robbie Robertson, hockey commentator Howie Meeker, Acadian filmmaker Phil Comeau, former cabinet minister Anne McLellan and Trudeau biographer Stephen Clarkson.

Fox was honoured for his efforts on behalf of those suffering from Parkinson’s disease, as well as his television and film work.

Fox, diagnosed with Parkinson’s two decades ago, called the award a great honour.

He chuckled that he felt like an imposter when he glanced around at his fellow inductees.

“I don’t begin for a second to put myself in the league of any of these people,” he said. “When I listen to what they’ve done, that’s Canadian to me. It’s a seriousness and a sense of humour, it’s a lot of contradictions.”

He said Canada always makes him think “of vast spaces and tight communities.”

“We think of ourselves huddled against the elements and helping each other. It’s very moving to be part of it.”

https://www.thestar.com/entertainment/michael-j-fox-receives-order-of-canada/article_8f612aa5-9d87-5133-9984-8c2b1b3eaa4f.html |

|

|

|

|

10 momentos clave en este video

|

|

|

|

|

It gets even more intriguing when Pan Am 103 is added to the correlation. First, it needs to be mentioned that the same Quatrain VI-97 had been very closely associated to another notorious plane crash - TWA 800 (as shown in 'Babylon Matrix'). And again, somehow, another major and equally notorious place crash, Pan Am 103, comes to relate to the same quatrain. Besides the timing (i.e. coinciding with the bombing of Novi Sad), an interesting correlation can be made with VI-97's fourth line, "When they want to have proof of the Normans", as one of the Scottish prosecutors for the trial is named 'Norman' (McFadyen) as mentioned in the news article. Obviously, the "proof of (the) Norman(s)" is to be a key part of the trial, thus nicely fitting the line.

Next, the involvement of Scotland in the Pan Am 103 incident turns out to be significant through Scotland's strong historical connection to the Masonic/Templar tradition from which the stories of the Ark/Grail cannot be separated. What fills the gaps between the issues (Pam Am 103/Scotland, Ark/Grail, VI-97, etc.) is yet another plane crash, the crash of Swissair 111 (Sept. 2, '98) off Nova Scotia, Canada, which was en route from NYC to Geneva, Switzerland. It is one of the most recent major airplane crashes. It is rather congruent that a recent major plane crash, Swissair 111, is to be linked, as we will see, with both TWA 800 and Pan Am 103, as both of those two airplane incidents made the headlines recently (the story of TWA 800's crash itself, and the story about the handover of the suspects of Pan Am 103) and both are hypothesized to be connected to Quatrain VI-97.

The link between TWA 800 and Swissair 111 is insinuated by the fact that both crashed mysteriously soon after taking off from NYC. Those incidents were only about 1 year apart (July '97 and Sept. '98). The connection between Swissair 111 and Pan Am 103 is first suggested in the name 'Nova Scotia' (where the Swissair 111 crash occurred) which means 'New Scotland' (Pan Am 103 exploded over Scotland). Notice that the "New" part can relate to VI-97's "new city" and it also happens that Nova Scotia is nicely bisected by the "45 degrees" N latitude, and Nova Scotia is historically closely connected with France (=> "Normans"). Furthermore, Swissair 111's destination Switzerland is roughly at "45 degrees" N., and the name Switzerland is derived from a word that means 'to burn' - as in "45 degrees the sky will burn" (!) (it's, therefore, interesting that the capital of Switzerland is called 'Bern'), strengthening the connection between Swissair 111 and VI-97.

And here are some Scotland-Nova Scotia connections that will shift the focus to the new 'associative matrix' of Ark/Grail. It happens that Nova Scotia, like Scotland, is also involved in the Templar tradition and the 'Holy Grail'. Nova Scotia, it turns out, is exactly where the 'Holy Grail' (whatever it may represent) is theorized by some scholars to have been taken by the Knights Templar. In support of this theory, the region of Nova Scotia and the land around it was called 'Acadia' by the French which closely resembles 'Arcadia' which is a term that is very closely associated with the Grail tradition.

The involvement of Switzerland is also very significant as it is a country theorized by some to be founded by the Templars - the country's flag (white cross on red background - the reverse of the Templar symbol of 'red/rose cross') and its famous banking business (the Templars essentially founded the banking system we use today) strongly suggests this, for example. It is also interesting to note that Switzerland is located largely on the Alps which forms a big 'arc' (that separates Italy, France and Switzerland) potentially relatable to the 'Ark' theme. Additionally, the word 'arktos', in Greek, resembling 'ark', refers to the constellation Ursa Major known to Egyptians as 'the thigh' - which can be correlated with the Alps/Switzerland because as you probably know Italy is shaped like a leg with a high-heel shoe and if you consider the size of the foot/shoe, anatomically the land of Italy would correspond to the calf and the Alps/Switzerland region would correspond to the thigh!

For subtler links, we can add that Paris, the destination of TWA 800, has as its landmark the 'Arc de Triomphe' (which was discussed extensively in my long piece, 'The Elysian Fields', so this connection is not as arbitrary as some of you might think), and the mythological character 'Paris' happens to be closely associated with 'torch', thus relating to the fire/flame/burn theme derived from VI-97. It should also be noted that the Statue of Liberty standing beside Long Island/'Fire' Island of NYC (with which TWA 800 and Swissair 111 are connected) which holds the 'torch' of freedom was given to U.S. by France, and there is a smaller replica of the statue in Paris. (For more detailed exposition on the link between the Statue of Liberty and Quatrain VI-97, see 'Babylon Matrix') Additionally, the flight number of the Swissair plane, '111', also seems to bear a subtle esoteric symbolism, as the Sumerian version of (Noah's) 'Ark' (which can be linked with the Ark of the Covenant in some ways) "was a cube - a modest one, measuring 60x60x60 fathoms, which represents the unit in the sexagesimal system where 60 is written as 1" (Hamlet's Mill, p219). So, the ark could also be seen as 1x1x1 or '111', the number of the plane.

https://www.goroadachi.com/etemenanki/1999-sirius.htm |

|

|

|

|

The lost history of the Freemasons

Amanda Ruggeri

Features correspondent

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Conspiracy theories abound about the Freemasons. But Scotland’s true Masonic history, while forgotten by many for centuries, remains hidden in plain sight.

With its cobblestone paving and Georgian façades, tranquil Hill Street is a haven in Edinburgh’s busy New Town. Compared to the Scottish capital’s looming castle or eerie closes, it doesn’t seem like a street with a secret.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Tranquil and historic, Edinburgh’s Hill Street attracts few tourists (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Walk slowly, though, and you might notice something odd. Written in gold gilt above a door framed by two baby-blue columns are the words, “The Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary’s Chapel) No 1”. Further up the wall, carved into the sandstone, is a six-pointed star detailed with what seem – at least to non-initiates – like strange symbols and numbers.

Located at number 19 Hill Street, Mary’s Chapel isn’t a place of worship. It’s a Masonic lodge. And, with its records dating back to 1599, it’s the oldest proven Masonic lodge still in existence anywhere in the world.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

At 19 Hill Street, look up to see this six-pointed star, a Masonic symbol (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That might come as a surprise to some people. Ask most enthusiasts when modern Freemasonry began, and they’d point to a much later date: 1717, the year of the foundation of what would become known as the Grand Lodge of England. But in many ways, Freemasonry as we know it today is as Scottish as haggis or Harris tweed.

From the Middle Ages, associations of stonemasons existed in both England and Scotland. It was in Scotland, though, that the first evidence appears of associations – or lodges – being regularly used. By the late 1500s, there were at least 13 established lodges across Scotland, from Edinburgh to Perth. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 16th Century that those medieval guilds gained an institutional structure – the point which many consider to be the birth of modern Freemasonry.

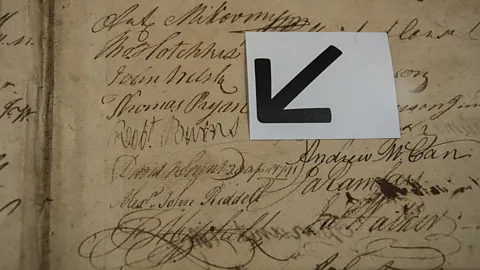

Take, for example, the earliest meeting records, usually considered to be the best evidence of a lodge having any real organisation. The oldest minutes in the world, which date to January 1599, is from Lodge Aitchison’s Haven in East Lothian, Scotland, which closed in 1852. Just six months later, in July 1599, the lodge of Mary’s Chapel in Edinburgh started to keep minutes, too. As far as we can tell, there are no administrative records from England dating from this time.

“This is, really, when things begin,” said Robert Cooper, curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and author of the book Cracking the Freemason’s Code. “[Lodges] were a fixed feature of the country. And what is more, we now know it was a national network. So Edinburgh began it, if you like.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

The Grand Lodge of Scotland, also known as Freemasons Hall, stands in the heart of Edinburgh’s New Town (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

I met Cooper in his office: a wood-panelled, book-stuffed room in the Grand Lodge of Scotland at 96 George Street, Edinburgh – just around the corner from Mary’s Chapel. Here and there were cardboard boxes, the kind you’d use for a move, each heaped full with dusty books and records. Since its founding in 1736, this lodge has received the records and minutes of every other official Scottish Masonic lodge in existence. It is also meant to have received every record of membership, possibly upwards of four million names in total.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

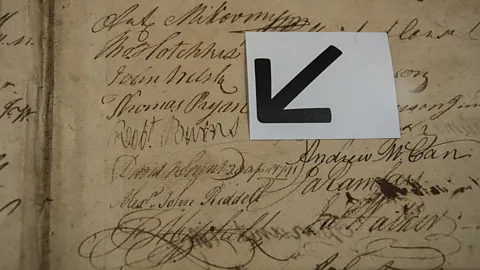

One of the items on display at the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum is its membership record with the signature of famed Freemason Robert Burns (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That makes the sheer number of documents to wade through daunting. But it’s also fruitful, like when the Grand Lodge got wind of the Aitchison’s Haven minutes, which were going for auction in London in the late 1970s. Another came more recently when Cooper found the 115-year-old membership roll book of a Scottish Masonic lodge in Nagasaki, Japan.

“There’s an old saying that wherever Scots went in numbers, the first thing they did was build a kirk [church], then they would build a bank, then they would build a pub. And the fourth thing was always a lodge,” Cooper said, chuckling.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

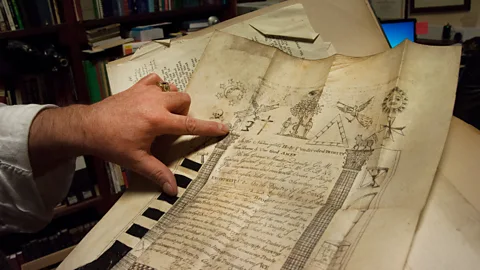

The curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, Robert Cooper, looks over the lodge’s museum (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That internationalism was on full display in the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum, which is open to the public. It was full of flotsam and jetsam from around the world: a green pennant embroidered with the “District Grand Lodge of Scottish Freemasonry in North China”; some 30 Masonic “jewels” – or, to non-Masons, medals – from Czechoslovakia alone.

Of course, conspiracy theorists find that kind of reach foreboding. Some say Freemasonry is a cult with links to the Illuminati. Others believe it to be a global network that’s had a secret hand in everything from the design of the US dollar bill to the French Revolution. Like most other historians, Cooper shakes his head at this.

“If we’re a secret society, how do you know about us?” he asked. “This is a public building; we’ve got a website, a Facebook page, Twitter. We even advertise things in the press. But we’re still a ‘secret society’ running the world! A real secret society is the Mafia, the Chinese triads. They are real secret societies. They don’t have a public library. They don’t have a museum you can wander into.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Cooper points to the Masonic symbols on one of the many historic documents in the lodge’s archive (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Some of the mythology about Freemasonry stems from the mystery of its early origins. One fantastical theory goes back to the Knights Templar; after being crushed by King Philip of France in 1307, the story goes, some fled to Argyll in western Scotland, and remade themselves as a new organisation called the Freemasons. (Find out more in our recent story about the Knights Templar).

Others – including Freemasons themselves – trace their lineage back to none other than King Solomon, whose temple, it’s said, was built with a secret knowledge that was transferred from one generation of stonemason to the next.

A more likely story is that Freemasonry’s early origins stem from medieval associations of tradesmen, similar to guilds. “All of these organisations were based on trades,” said Cooper. “At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’.”

At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’ – Robert Cooper

For all of the tradesmen, having some sort of organisation was a way not only to make contacts, but also to pass on tricks of the trade – and to keep outsiders out.

But there was a significant difference between the tradesmen. Those who fished or gardened, for example, would usually stay put, working in the same community day in, day out.

Not so with stonemasons. Particularly with the rush to build more and more massive, intricate churches throughout Britain in the Middle Ages, they would be called to specific – often huge – projects, often far from home. They might labour there for months, even years. Thrown into that kind of situation, where you depended on strangers to have the same skills and to get along, how could you be sure everyone knew the trade and could be trusted? By forming an organisation. How could you prove that you were a member of that organisation when you turned up? By creating a code known by insiders only – like a handshake.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Edinburgh's Lodge of Journeyman Masons No. 8 was founded in 1578; this lodge was built for it on Blackfriars Street in 1870 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Even if lodges existed earlier, though, the effort to organise the Freemason movement dates back to the late 1500s. A man named William Schaw was the Master of Works for King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England), which meant he oversaw the construction and maintenance of the monarch’s castles, palaces and other properties. In other words, he oversaw Britain’s stonemasons. And, while they already had traditions, Schaw decided that they needed a more formalised structure – one with by-laws covering everything from how apprenticeships worked to the promise that they would “live charitably together as becomes sworn brethren”.

In 1598, he sent these statutes out to every Scottish lodge in existence. One of his rules? A notary be hired as each lodge’s clerk. Shortly after, lodges began to keep their first minutes.

“It’s because of William Schaw’s influence that things start to spread across the whole country. We can see connections between lodges in different parts of Scotland – talking to each other, communicating in different ways, travelling from one place to another,” Cooper said.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

This oil painting at the Grand Lodge of Scotland shows Robert Burns’ inauguration at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, which was founded in 1677 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s influence was soon overshadowed. With the founding of England’s Grand Lodge, the English edged out in front of the movement’s development. And in the centuries since, Freemasonry’s Scottish origins have been largely forgotten.

“The fact that England can claim the first move towards national organisation through grand lodges, and that this was copied subsequently by Ireland (c 1725) and Scotland (1736), has led to many English Masonic historians simply taking it for granted that Freemasonry originated in England, which it then gave to the rest of the world,” writes David Stevenson in his book The Origins of Freemasonry.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Hidden in plain sight on Brodie’s Close off of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, the Celtic Lodge of Edinburgh and Leith No. 291 was founded in 1821 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Cooper agrees. “It is in some ways a bit bizarre when you think of the fact that we have written records, and therefore membership details, and all the plethora of stuff that goes with that, for almost 420 years of Scottish history,” he said. “For that to remain untouched as a source – a primary source – of history is really rather odd.”

One way in which most people associate Freemasonry and Scotland, meanwhile, is Rosslyn Chapel, the medieval church resplendent with carvings and sculptures that, in the wake of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, many guides have explained as Masonic. But the building’s links to Masonry are tenuous. Even a chapel handbook published in 1774 makes no mention of any Masonic connections.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s true Masonic history, it turns out, is more hidden than the church that Dan Brown made famous. It’s just hidden in plain sight: in the Grand Lodge and museum that opens its doors to visitors; in the archivist eager for more people to look at the organisation’s historical records; and in the lodges themselves, tucked into corners and alleyways throughout Edinburgh and Scotland’s other cities.

Their doors may often be closed to non-members, but their addresses, and existence, are anything but secret.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20161209-secret-history-of-the-freemasons-in-scotland |

|

|

|

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

http://westfordknight.blogspot.com/2018/09/columbus-and-templars.html |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

7 a 21 de 21

Siguiente Anterior

7 a 21 de 21

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

https://www.oakislandlegend.com/the-old-gold-salvage-and-wrecking-company.html

https://www.oakislandlegend.com/the-old-gold-salvage-and-wrecking-company.html