|

|

FRENCH REVOLUTIONARY (DECIMAL) TIME

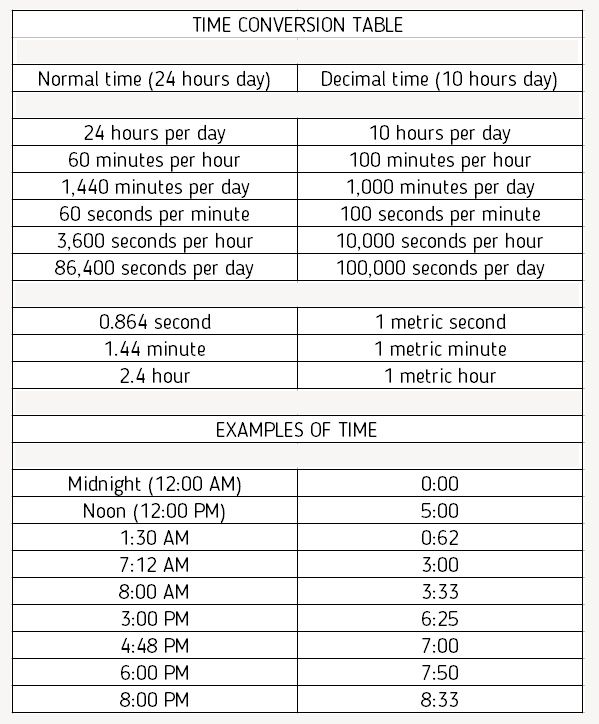

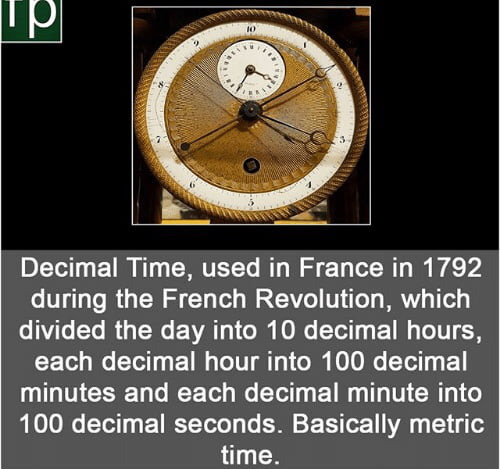

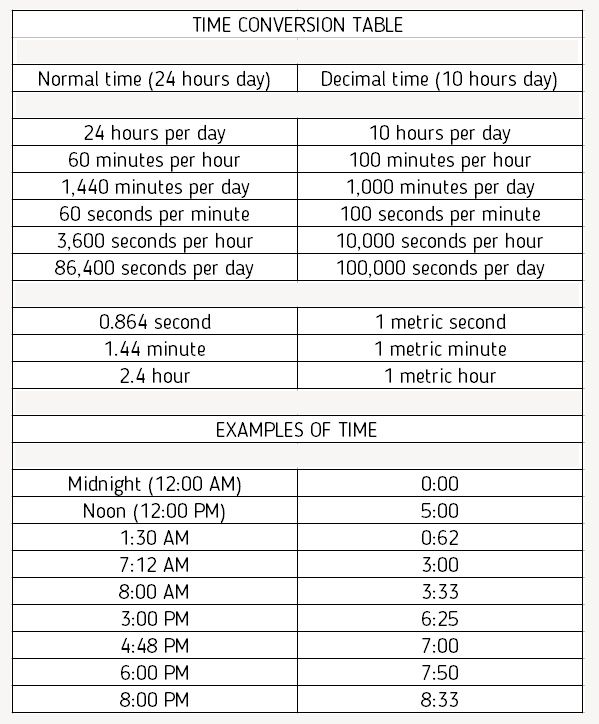

Everybody knows that there are 24 hours in a day, 60 minutes in an hour, and 60 seconds in minute. But in 1793, the French smashed the old clock system in favor of French Revolutionary Time, which was a 10-hour day, with 100 minutes per hour, and 100 seconds per minute. This thoroughly modern system had a few practical benefits, chief among them being a simplified way to do time-related math. If we want to know when a day is 80% complete, decimal time simply says "at the end of the eighth hour," whereas standard time requires us to say "at 19 hours, 12 minutes." French Revolutionary Time was a more elegant solution to that math problem. The problem was that every living person already had a well-established way of telling the time, and old habits die hard!

French Revolutionary Time officially began on November 24, 1793 although conceptual work around the system had been going on since the 1750s. The French manufactured clocks and watches showing both decimal time and standard time on their faces (allowing for both conversion and confusion). These clock faces were spectacularly weird. French Revolutionary Time officially began on November 24, 1793 although conceptual work around the system had been going on since the 1750s. The French manufactured clocks and watches showing both decimal time and standard time on their faces (allowing for both conversion and confusion). These clock faces were spectacularly weird.

The system proved unpopular. People were unfamiliar with switching systems of time, and there were few practical reasons for non-mathematicians to change how they told time. (The same could not be said of the metric system of weights and measurements, which helped to standardize commerce; weights and measurements often differed in neighboring countries, but clocks generally did not.) Furthermore, replacing every clock and watch in the country was an expensive proposition. The French officially stopped using decimal time after just 17 months. French Revolutionary Time became non-mandatory starting on April 7, 1795. This didn't stop some areas of the country from continuing to observe decimal time, and a few decimal clocks remained in use for years afterwards, presumably leading to many missed appointments!

LIVE NORMAL AND DECIMAL TIME

Live NORMAL time

Live DECIMAL time

DECIMAL TO NORMAL / NORMAL TO DECIMAL TIME CONVERTER

Some applications using decimal time are available in both Google Play and the Apple Store. For example, for Android - DecimalTime ; for Apple - DeciTime .

LOOK/PURCHASE SVALBARD DECIMAL TIME WATCHES

IMAGES OF DECIMAL CLOCKS AND WATCHES

https://svalbard.watch/pages/about_decimal_time.html |

|

|

Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 12 de 12

Següent

Anterior

2 a 12 de 12

Següent

Darrer

Darrer

|

|

|

It was proposed in general in 1788 by Claude Boniface Collignon, and proposed to the National Convention in 1793 by Jean-Charles de Borda, one of the multiple prominent French technocratic military engineers of the era. It was only passed in late 1794, and then shelved in mid-1795, with well less than a year of use.

Complaints at the time included the massive cost of replacing clocks - far more costly than simple rulers and weights - especially while a war of national survival was going on. But another was the massively widespread and above all frequent use of timekeeping. Even units of distance and weight don’t come up in everyday life as often as time of day, and everyone was used to the old ways. The French Revolutionary calendar lasted longer, but eventually it was also shelved by Napoleon in 1806, and only what we know as the metric system for other quantities survived.

A few clocks were produced with decimal time, and many included the traditional system of hours too.

Overall, even when everyone knows the complexities and what may be regarded as irregular ‘flaws’, far more involved and arcane systems that are much more complicated to learn can have massive cultural inertia when getting everyone to change system would go against extremely frequent habit, even if legally unenforced (for example, English orthography!). That said, the decimal system itself is a cultural choice, probably an artefact of our ten fingers, and numbers like 60 and 24 are highly divisible (having many factors), which is helpful - so it’s not so clearly that much worse.

There was another recommendation to decimalise time in the 1897 by a commission led by Henri Poincaré (of the famous conjecture and regarded by many as the founder of modern topology, certainly algebraic topology, and cousin of the later technocratic prime minister), though it never became law, but it too was left by the wayside.

On a related note, another longer-lasting but now also essentially defunct quantity that the French Revolution decimalised was angle: the grade, later grad or gon, was 1/100 of a right angle. Scientific calculators still offered it, pretty much unused, until recently, and (as an anecdotal aside) it has a bit of a humorous status among STEM students and professors from that era. This encountered a bigger problem: although there is no very fundamental unit of time (at least none that would also be practical for ordinary use, so the tiny Planck time aside…) and decimalisation makes sense for convenient compatibility with our general number system, angle actually does have a ‘natural’ unit which makes many fundamental formulas particularly neat: the radian, the angle subtended by an arc the same length as the radius, or 1/2π of a full 360 degree revolution. If we want to be more scientific, then, there seems little value to the ‘middle’ role of the grad, and the existence of three systems is itself an inconvenience. Nevertheless, it was used in at least some quarters for far longer than decimal time, used less often than time but arguably a tiny bit more convenient for engineers and architects, etc. than degrees and radians.

https://www.reddit.com/r/AskHistorians/comments/qh3kju/in_1792_france_experimented_with_decimal_time/ |

|

|

|

|

Learn French anytime you want to!

Whether you want to start learning French “à vingt heures ” (at 8 PM) or tomorrow morning, you can learn French anytime, on your own way, and at your own pace, via Busuu’s free online courses and learning resources!

How to ask the time in French

Let’s start with the casual way of asking the time that works in most situations. You can use this mode to communicate with friends, family, or someone that you already know.

Il est quelle heure ? - What time is it? Est-ce que tu as l’heure ? - Do you know the time?

If you want to be more polite and respectful to the other person, or if you’re speaking with a stranger, then you can use these more formal phrases:

Est-ce que vous avez l’heure, s’il vous plaît ? — Do you have the time, please? Auriez-vous l’heure, s’il vous plaît ? - Would you please have the time? Quelle heure est-il, s'il vous plait? — What is the time, please?

And if you’re just casually asking a close friend for time, you can ask them

T’as l’heure ? - What’s the time?

You’ll be able to understand the time for sure if they show you on their watch, but if they read it out, you’ll need more vocab. Let's go the extra mile and learn how to tell the time.

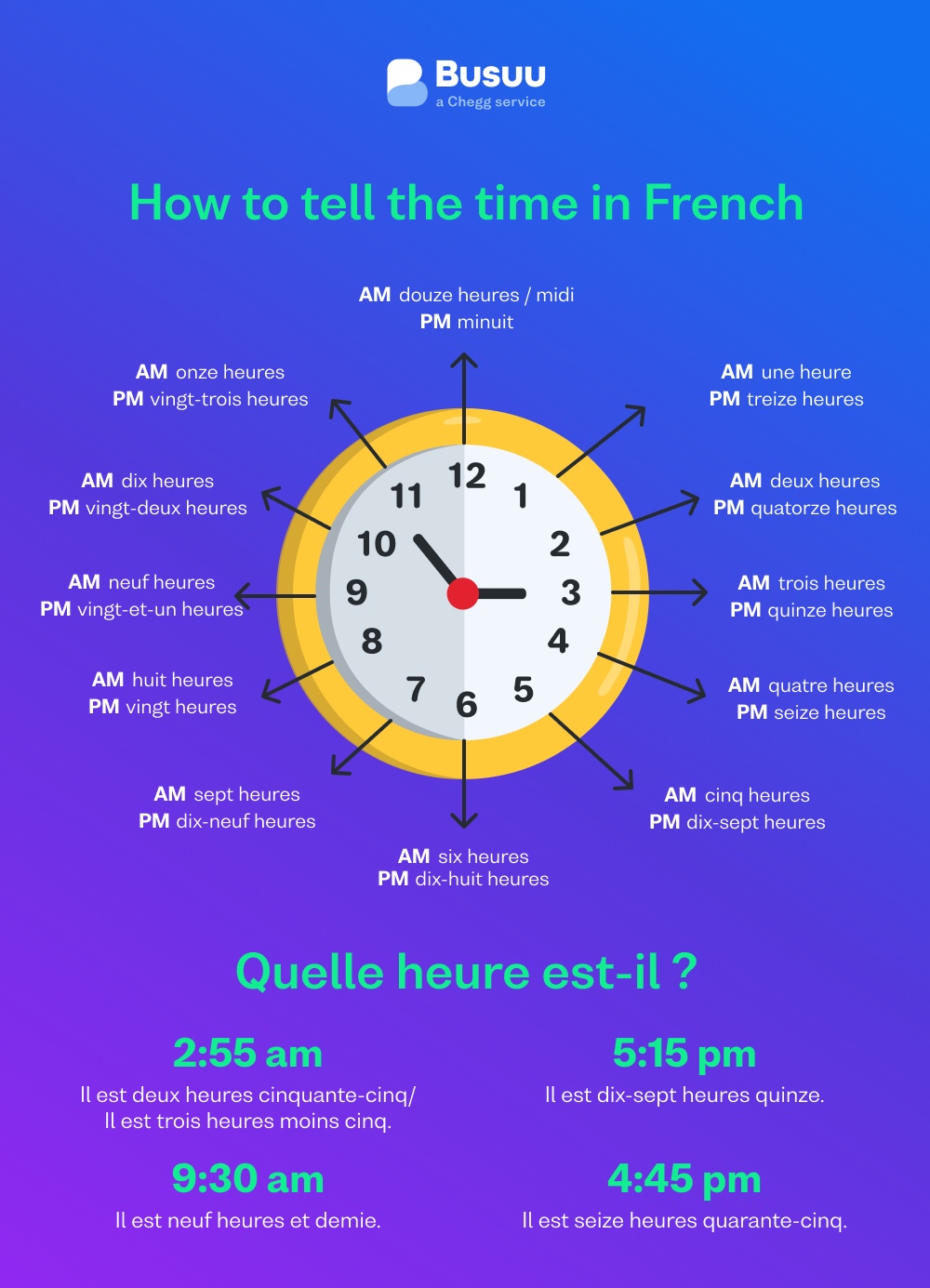

How to tell the time in French

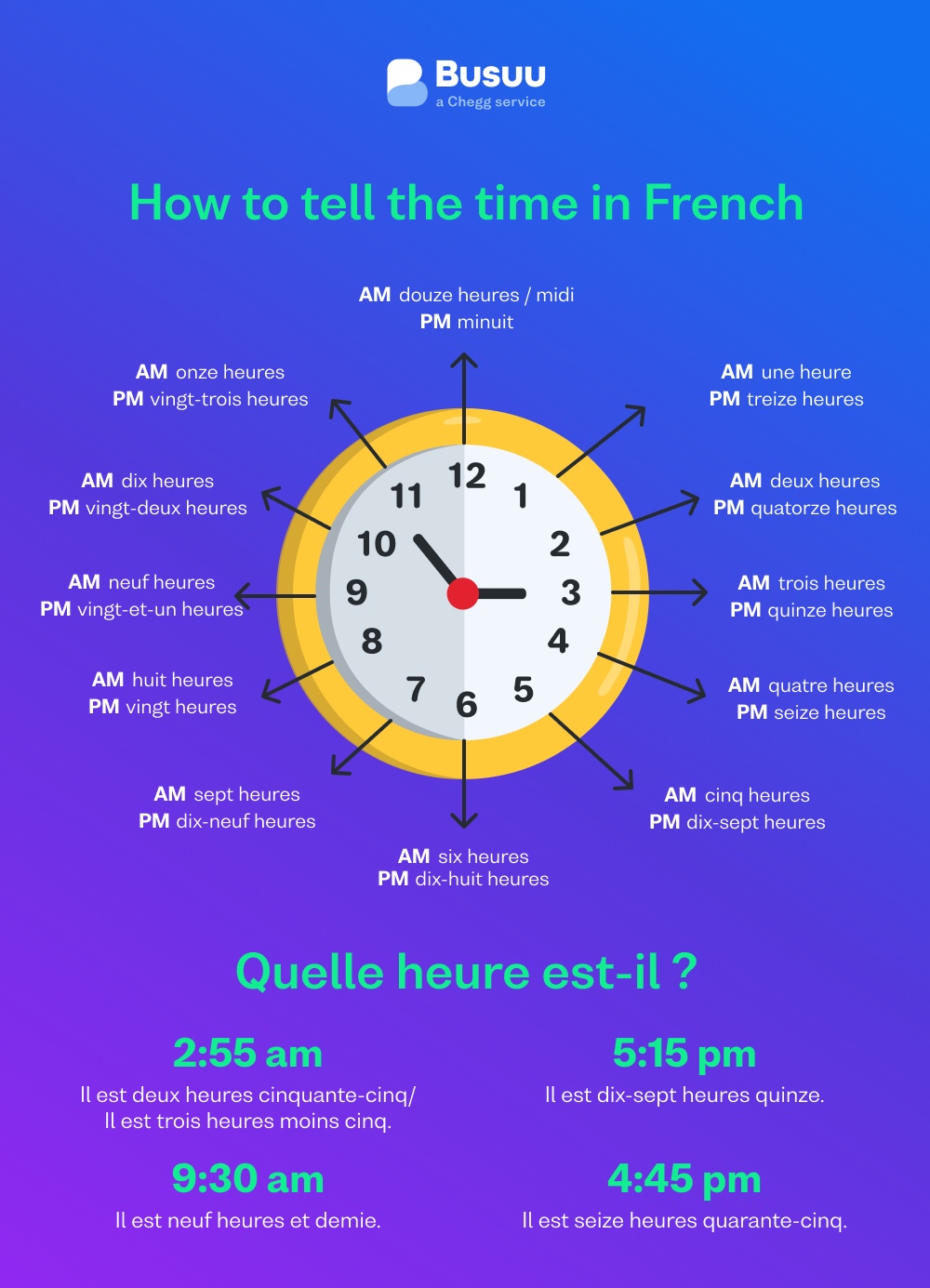

In French, time is based on the 24-hour clock, whereas in English, the 12-hour clock is used more frequently. The simplest and the most common way to tell the time in French is "il est" + Time (hours + minutes).

We measure time mainly with seconds, minutes, and hours:

Une heure/ les heures - hour/ hours Une minute/ les minutes - minute / minutes Une seconde/ les secondes - second / seconds

Let’s start with the hours in French (24-hour clock)

- It’s one o’clock. – Il est une heure.

- It’s two o'clock. – Il est deux heures.

- It’s three o’clock. – Il est trois heures.

- It’s four o’clock.– Il est quatre heures.

- It’s five o’clock. – Il est cinq heures.

- It’s six o’clock. – Il est six heures.

- It’s seven o’clock. – Il est sept heures.

- It’s eight o’clock. – Il est huit heures.

- It’s nine o’clock. – Il est neuf heures.

- It’s ten o’clock. – Il est dix heures.

- It’s eleven o’clock. – Il est onze heures.

- It’s twelve o’clock. – Il est douze heures/ il est midi.

Now the afternoon hours:

- It’s one o’clock. – Il est treize heures.

- It’s two o'clock. – Il est quatorze heures.

- It’s three o’clock. – Il est quinze heures.

- It’s four o’clock.– Il est seize heures.

- It’s five o’clock. – Il est dix-sept heures.

- It’s six o’clock. – Il est dix-huit heures.

- It’s seven o’clock. – Il est dix-neuf heures.

- It’s eight o’clock. – Il est vingt heures.

- It’s nine o’clock. – Il est vingt et une heures.

- It’s ten o’clock. – Il est vingt-deux heures.

- It’s eleven o’clock. – Il est vingt-trois heures.

- It’s twelve o’clock. – Il est minuit.

Now, to add the minutes (24-hour clock)

It is very easy to add in the minutes to the time, just mention the number of minutes after the hour.

For example:

- Il est 2 heures et cinquante-cinq minutes - It’s 2:55am

- Il est dix-sept heures et quinze minutes - it’s 5:15pm

- Il est neuf heures trente means it’s 9:30am

What time is it? It’s time to learn more French

Take your French learning to the next level with Busuu’s free online courses! Our bite-sized interactive lessons are designed by experts, and help you learn with feedback on your work from our global community of other online learners, all there to help you learn to speak like a local.

The time in French (12-hour clock)

When discussing time in French with the 12-hour clock, it’s similar to how you’d use the 24-hour clock, but you have to indicate clearly if you are referring to before noon or afternoon. In English, we’d use am or pm as indicators, but French uses this much less.

Here is some vocabulary that’ll help you indicate time of the day:

-

In the morning - du matin

-

In the afternoon - de l’après-midi

-

In the evening - du soir

-

Noon (12pm) - midi

-

Midnight (12pm) - minuit.

The fractions of time

There are ways to express time as fractions in French, such as saying, “It’s half past five.” Always remember to only use this with the 12-hour clock.

For 15 minutes past the hour — et quart E.g: Il est deux heures et quart – It’s a quarter past 2 (2:15pm)

For 30 minutes past the hour — et demie E.g: Il est 5 heures et demie – It’s half past five (5:30am)

For 15 minutes before the hour — moins le quart E.g: Il est une heure moins le quart – It is a quarter until 1 (12:45am)

Some bonus tips to help you learn the time in French

-

Using the 12-hour or 24-hour clock is entirely optional. However, the 24-hour clock is more straightforward and more commonly used across France and other European countries.

-

Fractions of time are only used with the 12-hour clock format.

-

Practice listening to the pronunciation of deux heures and douze heures. These are extremely similar, so you don’t want to confuse the two.

-

“Time” has different translations in French depending upon the context:

Time = hours of the day is - l’heure.

Time = duration is - le temps.

E.g: Depuis combien de temps apprenez-vous le français? — How long have you been studying French?

Time = frequency, i.e., the number of times - la fois

E.g: Combien de fois avez-vous visité la France ? — How many times have you visited France?

- To remember the date and time in French, you can set your phone language to French.

https://www.busuu.com/en/french/time |

|

|

|

|

Metric Time

Aside from you chronically late people, we all know how time works:

This system is okay. But also, it’s kind of crazy.

Why 60 minutes per hour? Why 60 seconds per minute? It goes back to Babylon, with their base 60 number system—the same heritage that gives us 360 degrees in a circle. Now, that’s all well and good for Babylon 5 fans, but our society isn’t base-60. It’s base-10. Shouldn’t our system of measuring time reflect that?

So ring the bells, beat the drums, and summon the presidential candidates to “weigh in,” because I hereby give you… metric time.

Now, this represents a bit of a change. The new seconds are a bit shorter. The new minutes are a bit longer. And the new hours are quite different—nearly two and a half times as long.

So why do this? Because it’d be so much easier to talk about time!

Here’s one improvement: analog clocks are easier to read. At first glance, the improvement may not be so obvious—we’ve simply reshuffled the numbers a bit.

But notice, the minute hand makes more sense now. When it’s at the 2, we’re 20 minutes past the hour. When it’s at the 7, we’re 70 minutes after the hour. And so on.

Second, times are no longer duplicated. For example, instead of needing to distinguish between 6am and 6pm, we can simply say “2:50” and “7:50.” (This is, of course, how “military time” currently works.)

Third—this is a big one—the time tells you how far through the day you are. The time 2:00 is exactly 20% of the way through the day. At 8:76, we’re exactly 87.6% of the way through the day.

Fourth, consider the moment when we’re 99.9% of the way through the day. In the new metric system, we get to watch the clock roll from 9:99 back around to 0:00. Isn’t that nicer and more conclusive than 11:59pm rolling around to 12:00am?

Fifth, it’s so much easier to talk about longer times. Two and a half days? That’s 25 hours. Three days and 6 hours? That’s simply 3.6 days. Since an hour is now a nice decimal fraction of a day, these conversions become easy.

Will there be adjustments to make? Certainly! But the adjustments are half of the fun.

Let’s start, as all good things do, with television. Whether you enjoy half-hour sitcoms or hour-long dramas, the length of your favorite shows is probably going to change. Why? Because, under our new system, what we now call “half an hour” will be 20.83 minutes. What we now call “an hour” will be 41.67.

There’s nothing magical about these “half-hour” and “hour” lengths, obviously. They were chosen simply because they were nice round numbers. But under the new system, they aren’t! Since it’d be silly to divide the TV schedule into 21-minute intervals, presumably television networks would tweak the lengths to go more evenly into an hour.

If so, they’d have two choices: 5 blocks per hour (i.e., two dramas, plus a sitcom), or 4 blocks per hour (i.e., two dramas).

If you choose the former, shows will be 4% shorter than today, leading to accelerated storytelling. (It’s the same change that’s unfolded over the last 20 years, as increased ad time has squeezed the shows themselves to be shorter.)

And if you choose the latter, shows will be 20% longer. They’ll perhaps unfold at a slower, more cinematic speed. Either way, expect the pacing and rhythm of TV shows to change.

Sports run into the same issue. Football will probably opt for four quarters of 10 minutes each, which shortens the game by 4%. Expect slightly diminished scoring as a result. (And, if we’re lucky, diminished concussions.)

Hockey, meanwhile, might go for three periods of 15 minutes each, which actually makes the game 8% longer. It might give someone a chance to tackle Wayne Gretzky’s scoring records (but then again, probably not—he’s way out of reach right now).

I’d expect soccer to select two halves of 30 minutes each, which (as with American football) shortens games by 4%. If you thought soccer was too high-scoring already, you’re in luck (and also in a very small minority, I suspect).

When it comes to sports, the lengths of games won’t be the only thing changing. We also need to reconsider record running times.

Usain Bolt’s world-record for the 100-meter dash (currently 9.58 seconds) would be, under the new system, 11.09 metric seconds. Doing the 100m in 11 metric seconds might be achievable in the future, but 10 seconds? Perhaps never. (That’s the equivalent of 8.64 of our seconds!)

What about the mile? Well, it’s a little funny to imagine a world with metric time still worrying about that strange unit of distance (5280 feet? Really?), but the famed 4-minute mile would correspond to a 2.78-minute mile.

This is weird because, for top runners in the 1940s and 1950s, the barrier to running a 4-minute mile may have been less physiological than psychological. Would the 2.8-minute mile have felt as intimidating? Would the 3-minute mile? Perhaps it’d be the 2.5-minute mile, seeing as the current world record (3:43 in our old system) is 2.58 metric minutes?

And we might as well mention the marathon, where the world record time (currently 2:02:57) is now under an hour: 85 minutes, 38 seconds. I suspect that the 1-hour marathon would be a real badge of honor, something that every distance runner aspires to.

Leaving sports aside, what about food?

Restaurants would open for breakfast at perhaps 3:00 or 3:50. (Of course, coffee shops like Starbucks might open as early as 2:50.)

You’d get lunch around 5:00—that is to say, noon. Under our current system, I feel silly eating before 11:30, which is 4:80 under the new system. But I wonder—would I feel comfortable grabbing lunch at 4:75? Perhaps even 4:60 (even though that’s earlier than 11am under our current scheme)?

Eating is psychological, and how we number our hours might steer our behavior.

As for dinner, I suspect 7:50 to 8:00 would be the preferred time (although the famously late-eating Spaniards might hold off until 8:75 or 9:00).

Other numbers change, too. Take speed limits: the typical 65mph limit on many highways translates to 156 mph under the new system; I suspect we’d see that bumped up to 160 mph or down to 150 mph for the sake of roundness (which translates to 66.7mph or 62.5mph under our current system).

The speed of sound? Not 340 meters per second any longer; it’s now just 294 meters per second. Meters haven’t changed, of course, but seconds have gotten shorter!

And the speed of light? Unfortunately, we lose the lovely number 300 million meters per second; instead, it becomes roughly 260 million meters per second.

Speaking of light, on the equinox, you get 5 hours of light and 5 hours of dark.

The winter solstice is pretty grim: in London, you’d see just 3 hours, 25 minutes, and 25 seconds of daylight.

The summer solstice is nice, though: London would get 6 hours, 93 minutes of sun.

Okay, time to come clean: I propose this without a single iota of seriousness. It’d be insane to ditch our current system. We’re used to it. We’ve agreed upon it. We’ve built our lives around it. The hassle of a change far outweighs the gains.

But I still love the thought experiment. It asks you, in some small way, to reimagine your life. How do you spend your time? How do you measure the success of a day? When you plan your hours, are you conceding to the arbitrary dictates of a quirky clock, or are you truly giving your tasks the time that they deserve? If I scrambled your sense of time, relabeling all your moments, would it change the way you feel about them? Do the numbers we assign to times matter? Or are we just scratching lines on the shifting dunes of eternity?

https://mathwithbaddrawings.com/2015/04/16/metric-time/ |

|

|

|

|

The new metric time wouldn’t fitting in with the rotation of the planet. rendered this idea impractical, at best.

100 (secs) x 100 (mins) x 10 (hrs) would have made a metric day 100,000 seconds.

Our normal day based on the rotation of the planet is:

60 (secs) x 60 (mins) x 24 (hrs) making a standard day 86,400 seconds.

So a metric day would have been 13,600 seconds, or 3.77 standard hours longer (assuming a second was the same length of time in both systems of measurement).

After 3 metric days we would have been 11.33 standard hours out of sync with a natural day. At midnight the sun would have been high in the sky.

Answered: In 1792, France experimented with decimal time, making a day 10 hours, an hour 100 minutes, and a minute 100 seconds. Why did this new standard for timekeeping not take off when so much of the world uses a base 10 system for measuring stuff?

https://www.quora.com/In-1793-decimal-time-was-tried-in-the-French-Revolution-10-hr-day-x-100-min-hr-x-100-sec-min-instead-of-24-x-60-x-60-Why-was-decimal-time-unsuccessful-after-1795 |

|

|

|

|

I don’t know if it’s a right answer but I think it’s because the numerical system used was/is decimal

Known in the west as arabic number (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9) but originated from India it’s a decimal system (ten symbols)

and the vast majority of human numerical system is decimal.

I guess that’s why.

But yes the base 12 system would have been interesting (not only for measurment but priorly for mathematics)

divider in decimal system 2 and 5

divider in 12 system 3, 2 and 2 again

https://www.quora.com/In-1793-decimal-time-was-tried-in-the-French-Revolution-10-hr-day-x-100-min-hr-x-100-sec-min-instead-of-24-x-60-x-60-Why-was-decimal-time-unsuccessful-after-1795 |

|

|

|

|

Decimal Time: How the French Made a 10-Hour Day

Everybody knows that there are 24 hours in a day, 60 minutes in an hour, and 60 seconds in minute.* But in 1793, the French smashed the old clock in favor of French Revolutionary Time: a 10-hour day, with 100 minutes per hour, and 100 seconds per minute. This thoroughly modern system had a few practical benefits, chief among them being a simplified way to do time-related math: if we want to know when a day is 70 percent complete, decimal time simply says "at the end of the seventh hour," whereas standard time requires us to say "at 16 hours, 48 minutes." French Revolutionary Time was a more elegant solution to that math problem. The trick was that every living person already had a well-established way to tell time, and old habits die hard.

Noon is at Five in Decimal Time

French Revolutionary Time officially began on November 24, 1793, although conceptual work around the system had been going on since the 1750s. The French manufactured clocks and watches showing both decimal time and standard time on their faces (allowing for conversion and confusion).

The system proved unpopular. People were unfamiliar with switching systems of time, and there were few practical reasons for non-mathematicians to change how they told time. (The same could not be said of the metric system of weights and measurements, which helped to standardize commerce; weights and measurements often differed in neighboring countries, but clocks generally did not.) Furthermore, replacing every clock and watch in the country was a spendy proposition. The French officially stopped using decimal time after just 17 months: French Revolutionary Time became non-mandatory starting on April 7, 1795. This didn't stop some areas of the country from continuing to observe decimal time, and a few decimal clocks remained in use for years afterwards, presumably leading to many missed appointments.

Other Attempts at Decimal Time

The French Republican Calendar was another attempt by revolutionary France to decimalize everything. It wasn't particularly successful.

The French tried again in 1897, when the Commission de Décimalisation du Temps proposed a 24-hour day with 100-minute hours, again with 100 seconds per minute. This proposal was scrapped in 1900.

And then, of course, there's the Stardate, a pseudo-decimal system of date measurement used in Star Trek. Unsurprisingly, the Stardate started out being supremely imprecise and was just supposed to sound futuristic; here's a snippet from the Star Trek Guide for teleplay writers on the original series:

"Pick any combination of four numbers plus a percentage point, use it as your story's stardate. For example, 1313.5 is twelve o'clock noon of one day and 1314.5 would be noon of the next day. Each percentage point is roughly equivalent to one-tenth of one day."

And lest we forget Swiss watchmakers in all of this, Swatch introduced their own bizarre decimal time system in 1998. Called Swatch Internet Time, it divided the day into ".beats" (yes, with a dot) and referred to a particular .beat using the @ symbol (so you might say, "ICQ me at @484 so we can swap some beenz, LOL!"). Each .beat lasted 1 minute and 26.4 seconds and represented 1/1000 of a day. Nope, not confusing @all.

* = There are actually several exceptions to the 24/60/60 rule, most notably leap seconds, but let's keep it simple.

A version of this story ran in 2013; it has been updated for 2021.

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/32127/decimal-time-how-french-made-10-hour-day |

|

|

|

|

France had a calendar with 10-hour days during the revolution.

French Revolutionary Time was a short-lived concept that used a base-10 timekeeping system. Otherwise known as “decimal time,” this unprecedented method included 10-hour days, 100 minutes per hour, and 100 seconds per minute. Each day was divided into 10 equal parts, with “zero” marking the start (what is now midnight) and “five” denoting the midpoint (noon). This meant that every hour was more than twice as long as an hour of standard time. New clocks and watches were even manufactured displaying both decimal time and standard time, to considerable confusion.

While France formally adopted this practice on November 24, 1793, the idea was first promoted in 1754. That year, mathematician Jean le Rond d’Alembert drew inspiration from the base-10 numeral system that had existed since ancient times and argued that it would be easier and more convenient to calculate times that were divisible by 10. The concept was revived in 1788 and met with enthusiasm from French revolutionaries seeking to shed their ties to the past. French Revolutionary Time was later adopted by the French Parliament, though it proved to be unpopular among citizens who found the switch confusing. The new system was deemed optional on April 7, 1795, and the country ultimately reverted to the previous timekeeping method.

In addition to changing how the country kept time, revolutionary France also adopted the French Republican calendar. The new formula divided the year into 12 months, each of which contained three 10-day weeks. To bring the total days up to 365, France tacked on five additional days at the end of the year as holidays. Debuted on October 24, 1793, the new calendar was also short-lived, and was abolished by Napoleon Bonaparte on January 1, 1806.

You may also like

By the Numbers

DID YOU KNOW?

September 1752 was only 19 days long in Britain.

In 1752, the month of September was only 19 days long throughout the British Empire (including its colonies in America), due to the Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750. That parliamentary move transferred the British from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, the former having overestimated each year's length by about 11 minutes. Back in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII had declared that all countries under the dominion of the Catholic Church needed to adopt the Gregorian calendar, but many Protestant nations — including England — resisted those demands. When Britain finally converted to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 in an effort to catch up with other nations, the country jumped straight from September 2 to September 14, skipping the 11 days in between to account for the errors of the old calendar.

https://historyfacts.com/world-history/fact/france-had-a-calendar-with-10-hour-days-during-the-revolution/ |

|

|

|

|

Tiempo decimal

Se denomina tiempo decimal a la expresión de la extensión del día utilizando unidades que se encuentran relacionadas mediante un sistema decimal. Este término es utilizado para referirse específicamente al tiempo revolucionario francés, el cual divide al día en 10 horas decimales, cada hora decimal en 100 minutos decimales y cada minuto decimal en 100 segundos decimales, en contraposición al tiempo estándar usual, en el cual el día se divide en 24 horas, cada hora en 60 minutos y cada minuto en 60 segundos.

Reloj decimal francés de la época de la Revolución francesa.

El tiempo decimal fue utilizado en China a lo largo de casi toda su historia junto con el tiempo duodecimal. Hacia el año 1000 a. C. el día que se extendía desde una medianoche a la medianoche siguiente se encontraba dividido en 12 horas dobles (chino tradicional: 時辰; chino simplificado: 时辰; pinyin: shíchen) y 100 ke (Hanzi: 刻; Pinyin: kè).[1] Durante tres períodos breves se utilizaron un número diferente de kes por día, 120 ke durante 5–3 A.d. C., 96 ke durante 507–544, y 108 ke durante 544–565. Varios de los casi 50 calendarios chinos también dividieron cada ke en 100 fen, aunque en otros cada ke era dividido en 60 fen. En 1280, el calendario Shoushi (Season Granting) subdividió a cada fen en 100 miao, creando un sistema decimal completo de 100 ke, 100 fen y 100 miao.[2] El tiempo decimal chino dejó de ser utilizado en 1645 cuando el calendario Shixian (Constant Conformity), basado en la astronomía europea llevada a China por los jesuitas, adoptó 96 ke por día junto con 12 horas dobles, con lo cual cada ke corresponde exactamente a un cuarto de hora.[3]

En tiempos modernos, el tiempo decimal fue introducido durante la Revolución francesa por un decreto promulgado el 5 de octubre de 1793:

- XI. Le jour, de minuit à minuit, est divisé en dix parties, chaque partie en dix autres, ainsi de suite jusqu’à la plus petite portion commensurable de la durée.

- XI. El día, desde medianoche hasta la medianoche siguiente, se divide en diez partes, cada parte a su vez se compone de diez partes, y así sucesivamente hasta la duración de tiempo más pequeña que se pueda medir.

Se les dio nombre a estas partes el 24 de noviembre de 1793 (4 Frimario del Año II). Las divisiones primarias se denominaron horas, y se agregó:

- La centième partie de l'heure est appelée minute décimale; la centième partie de la minute est appelée seconde décimale. (énfasis en el original)

- La centésima parte de una hora es denominada minuto decimal; la centésima parte de un minuto es denominada segundo decimal.

Por lo tanto, medianoche correspondía a la hora 10, mediodía a la hora 5, etc. Si bien se fabricaron relojes con cuadrantes mostrando el tiempo estándar con los números 1–24 y el tiempo decimal con los números 1–10, el tiempo decimal nunca contó con gran aceptación; no fue utilizado de manera oficial hasta comienzos del año Republicano III, 22 de septiembre de 1794, y el uso obligatorio fue suspendido el 7 de abril de 1795 (18 Germinal del Año III), mediante la misma ley que introdujo el sistema métrico original. Por lo tanto, inicialmente el sistema métrico no poseía una unidad de tiempo, y versiones posteriores del sistema métrico utilizan el segundo, igual a 1/86400 de día, como unidad de tiempo métrico.

El tiempo decimal fue introducido como parte del calendario republicano francés, en el cual además de dividir el día en forma decimal, dividió al mes en tres décadas de 10 días cada una; este calendario fue abolido a finales del 1805. El comienzo de cada año era determinado según el día en él tenía lugar el equinoccio de otoño, en relación con el tiempo solar aparente o verdadero en el Observatorio de París. El tiempo decimal habría sido expresado también según el tiempo solar aparente, dependiendo de la posición desde la cual se lo registraba, como ya era la costumbre general para ajustar los relojes.

En 1897 los franceses realizaron otro intento de decimalizar el tiempo, cuando se creó la Commission de décimalisation du temps en el Bureau des Longitudes, siendo secretario el matemático Henri Poincaré. La comisión propuso un compromiso, al mantener el día de 24 horas, pero dividir cada hora en 100 minutos decimales, y cada minuto en 100 segundos. El plan no tuvo buena acogida y fue abandonado en 1900.

Hay exactamente 86.400 segundos estándar (véase SI para una definición actual del segundo estándar) en un día estándar, pero en el sistema de tiempo decimal francés hay 100.000 segundos decimales en un día, por lo que el segundo decimal es más corto que su contraparte.

| Unidad decimal | Segundos | Minutos | Horas | h:mm:ss |

| Segundo decimal |

0,864 |

0,0144 |

0,00024 |

0:00:00,9 |

| Minuto decimal |

86,4 |

1,44 |

0,024 |

0:01:26,4 |

| Hora decimal |

8640 |

144 |

2,4 |

2:24:00,0 |

Son los científicos y los programadores de computadoras lo que utilizan en forma más asidua el tiempo decimal del día en forma de día fraccional. El tiempo estándar de 24 horas es convertido en un día fraccional simplemente mediante dividir el número de horas pasadas desde la medianoche por 24 para obtener una fracción decimal. Por lo tanto medianoche es 0,0 día, mediodía es 0,5 d, etc., lo cual se puede componer con cualquier tipo de fecha, tales como:

Es posible utilizar tantos sitios decimales como sea necesario de acuerdo a la precisión requerida, de forma que 0,5 d = 0,500000 d. Los días fraccionarios a menudo son expresados en UTC o TT, aunque las fechas Julianas utilizan fecha/tiempo astronómico anterior a 1925 (cada fecha comenzaba en el 0h por lo tanto ".0" = mediodía) y Microsoft Excel utiliza la zona de tiempo local de la computadora. El uso de días fraccionarios reduce el número de unidades utilizadas en cálculos de tiempo de cuatro (días, horas, minutos, segundos) a una sola (días). A menudo los astrónomos utilizan días fraccionarios para registrar sus observaciones, y fueron indicados haciendo referencia al Paris Mean Time por el matemático y astrónomo francés del siglo xviii Pierre-Simon Laplace en su libro, Traité de Mécanique Céleste, tal como en estos ejemplos:

... et la distance périhélie, égale à 1,053095 ; ce qui a donné pour l'instant du passage au périhélie, sept.29,10239, temps moyen compté de minuit à Paris.

Les valeurs précédentes de a, b, h, l, relatives à trois observations, ont donné la distance périhélie égale à 1,053650; et pour l'instant du passage, sept.29,04587; ce qui diffère peu des résultats fondés sur cinq observations.

Días fraccionales fueron utilizados durante el siglo xix por el astrónomo británico John Herschel en su libro, Outlines of Astronomy, como se ilustra en estos ejemplos:

Between Greenwich noon of the 22d and 23d of March, 1829, the 1828th equinoctial year terminates, and the 1829th commences. This happens at 0 d•286003, or at 4 h 51 m 50 s •66 Greenwich Mean Time ... For example, at 12 h 0 m 0 s Greenwich Mean Time, or 0 d•500000...

En general el sistema de segundos fraccionales es más utilizado que el de días fraccionales. En efecto, esta es la representación en una única unidad que utilizan numerosos lenguajes de programación, incluidos C, y parte de los estándares UNIX/POSIX utilizados por Mac OS X, Linux, etc.; para convertir días fraccionales en segundos fraccionales, multiplican el número por 86400. Tiempos absolutos son a menudo expresados relativos a la medianoche del 1 de enero de 1970. Otros sistemas pueden utilizar un punto cero distinto, pueden contar en milisegundos en vez de segundos, etc.

Tiempo de Internet Swatch

[editar]

El 23 de octubre de 1998, la compañía fabricante de relojes Suiza, Swatch, presentó un tiempo decimal denominado Swatch Internet Time, el cual divide al día en 1000 beats (cada uno 86,4 s) contados en el rango 000–999, con @000 medianoche y @500 mediodía CET (UTC +1), en contraposición al UTC.[4] La empresa ha vendido relojes que indican el Tiempo de Internet.

Internet Time ha sido criticado por utilizar un origen diferente al utilizado por el Horario universal, tergiversar CET al presentarlo como "Biel Mean Time", y por no tener unidades más precisas, aunque ciertas organizaciones han propuesto los "centibeats" (864 ms) y "milibeats" (86.4 ms).

Otros tiempos decimales

[editar]

Distintas personas han propuesto un rango de variaciones al tiempo decimal, dividiendo al día en diferente número de unidades y subunidades con diversos nombres. La mayoría están basados en días fraccionarios, de forma que un formato de tiempo decimal puede ser fácilmente convertido en otro, de forma tal que todos estos son equivalentes:

- 0,500 día fraccional

- 5h 0m tiempo decimal francés

- @500 Swatch Internet Time

- 50,0 centidía

- 500 milidía

- 50,0% Tiempo porcentual

- 12:00 Standard Time

Algunas propuestas de tiempo decimal están basadas en unidades de medidas alternativas del tiempo métrico. La diferencia entre el tiempo métrico y el tiempo decimal es que en el tiempo métrico se definen las unidades para medir intervalos de tiempo, tal como se lo mide con un cronómetro, mientras que el tiempo decimal define el tiempo del día, tal como lo mide un reloj. Así como el tiempo estándar utiliza como base el segundo la unidad métrica de tiempo, las escalas de tiempo decimal propuestas pueden utilizar otras unidades métricas.

|

|

|

Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 12 de 12

Següent

Anterior

2 a 12 de 12

Següent

Darrer

Darrer

|

French Revolutionary Time officially began on November 24, 1793 although conceptual work around the system had been going on since the 1750s. The French manufactured clocks and watches showing both decimal time and standard time on their faces (allowing for both conversion and confusion). These clock faces were spectacularly weird.

French Revolutionary Time officially began on November 24, 1793 although conceptual work around the system had been going on since the 1750s. The French manufactured clocks and watches showing both decimal time and standard time on their faces (allowing for both conversion and confusion). These clock faces were spectacularly weird.