|

|

8/8=220 DÍAS CALENDARIO GREGORIANO

|

|

|

|

|

Some genuinely superb posts on this internet site , thanks for contribution.

|

|

|

|

|

France had a calendar with 10-hour days during the revolution.

French Revolutionary Time was a short-lived concept that used a base-10 timekeeping system. Otherwise known as “decimal time,” this unprecedented method included 10-hour days, 100 minutes per hour, and 100 seconds per minute. Each day was divided into 10 equal parts, with “zero” marking the start (what is now midnight) and “five” denoting the midpoint (noon). This meant that every hour was more than twice as long as an hour of standard time. New clocks and watches were even manufactured displaying both decimal time and standard time, to considerable confusion.

While France formally adopted this practice on November 24, 1793, the idea was first promoted in 1754. That year, mathematician Jean le Rond d’Alembert drew inspiration from the base-10 numeral system that had existed since ancient times and argued that it would be easier and more convenient to calculate times that were divisible by 10. The concept was revived in 1788 and met with enthusiasm from French revolutionaries seeking to shed their ties to the past. French Revolutionary Time was later adopted by the French Parliament, though it proved to be unpopular among citizens who found the switch confusing. The new system was deemed optional on April 7, 1795, and the country ultimately reverted to the previous timekeeping method.

In addition to changing how the country kept time, revolutionary France also adopted the French Republican calendar. The new formula divided the year into 12 months, each of which contained three 10-day weeks. To bring the total days up to 365, France tacked on five additional days at the end of the year as holidays. Debuted on October 24, 1793, the new calendar was also short-lived, and was abolished by Napoleon Bonaparte on January 1, 1806.

You may also like

By the Numbers

DID YOU KNOW?

September 1752 was only 19 days long in Britain.

In 1752, the month of September was only 19 days long throughout the British Empire (including its colonies in America), due to the Calendar (New Style) Act of 1750. That parliamentary move transferred the British from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar, the former having overestimated each year's length by about 11 minutes. Back in 1582, Pope Gregory XIII had declared that all countries under the dominion of the Catholic Church needed to adopt the Gregorian calendar, but many Protestant nations — including England — resisted those demands. When Britain finally converted to the Gregorian calendar in 1752 in an effort to catch up with other nations, the country jumped straight from September 2 to September 14, skipping the 11 days in between to account for the errors of the old calendar.

https://historyfacts.com/world-history/fact/france-had-a-calendar-with-10-hour-days-during-the-revolution/ |

|

|

|

|

72. The Egyptian Royal Cubit, the Inch, the Metre, and 254

Updated: Apr 16, 2024

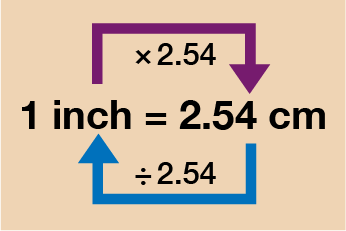

A centimetre is 2.54 inches. At Giza, the number 254 is found as a factor which links various linear dimensions. What does it mean to multiply or divide a linear measure by 254? What does it mean to convert inches to metres, or vice versa?

254 is not the only factor that links the key dimensions at Giza, but it is a common theme. The other factors seem to be based in geometry (such as π , √3), and astronomy (such as 223, 235 and 29.53059).

As 29.53059 x 4/3 inches are close to 10 000 / 254 inches, as are 365.242199 / 354.36708 x 100 / 2.61803 inches, they can be used almost interchangeably to interpret the dimensions at Giza.

10000 / 254 = 39.3700787402

29.53059 x 4/3 = 39.37412

365.242199 / 354.36708 x 100 / 2.61803 = 39.368871

The number 254 is linked to both astronomy and geometry. It is linked to pi, to Phi squared, and to the solar and lunar years, as well as being the number of sidereal months in a Metonic period.

When linear dimensions at Giza are multiplied or divided by 254, it's not necessarily that in one place inches were used and in another metres were used. The metre and the inch can both be said to co-exist at Giza, and even if the metre hadn't appeared in the 18th century it would still appear at Giza. But the use of 254 could in fact be a reference to the ratio between the solar and lunar years combined with Phi squared, or to pi divided by the mean number of lunations in a year.

If we think of possible links between the metre, the inch and the Egyptian royal cubit, the number 254 also makes an appearance, since 2.54 cm are an inch. Converting between inches and metres allows us to see ways of thinking about the Egyptian royal cubit, in relation to geometry and astronomy.

The links between these three units, inch, metre and cubit, and to astronomy and geometry, may hint at something of the symbolic and religious significance of the cubit in ancient Egyptian cosmology and astronomy. It could also explain some of the enduring appeal of the metre and the inch.

Another interesting connection to be made to the number 254 is that, as Howard Crowhurst points out in his book Carnac the Alignments, there are 127 kerb stones around the base of Knowth, in Ireland.

127 is a major prime number (...) and as such is a mirror of the fundamental prime number, One. But it is also half of 254 which is the number of lunar orbits in the 19 year Metonic cycle which also counts 235 full moons. The exact relationship between the metre length and the foot is also to be found through this number since 1 inch = 2.54 cm. Also a right angled triangle with a hypotenuse of 254 m and a base of 235 m has a third side measuring 100.0037 x √10 feet. (1)

The presence of the number 127 in Ireland seems to suggest a link to the repeated presence of 254 at Giza. The 127 stones at Knowth also suggest we should take the inch - metre connection seriously when analysing ancient sites.

https://www.mercurialpathways.com/post/72-the-egyptian-royal-cubit

|

|

|

|

|

Alignment of the Giza pyramids with data measured by Sir W. M. F. Petrie [6] (distances in m). Two numbers have been slightly corrected: The long diagonal is 936.16 m rather than 936.19 m, and one angle is 31° 55' 13' rather than 34° 10' 11' (explanation in [5, p. 96; 6, p. 125]). The relative elevations stem from S. Perring (see: [9, part IV, map 1]). Detailed information is provided in the drawings of Maragioglio and Rinaldi [9]. The angles were calculated from the original distances, given in inches (1 inch = 2.54 cm).

https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Alignment-of-the-Giza-pyramids-with-data-measured-by-Sir-W-M-F-Petrie-6-distances_fig3_359688325 |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

15 a 29 de 29

Següent Anterior

15 a 29 de 29

Següent

Darrer

Darrer

|

![Alignment of the Giza pyramids with data measured by Sir W. M. F. Petrie [6] (distances in m). Two numbers have been slightly corrected: The long diagonal is 936.16 m rather than 936.19 m, and one angle is 31° 55' 13' rather than 34° 10' 11' (explanation in [5, p. 96; 6, p. 125]). The relative elevations stem from S. Perring (see: [9, part IV, map 1]). Detailed information is provided in the drawings of Maragioglio and Rinaldi [9]. The angles were calculated from the original distances, given in inches (1 inch = 2.54 cm).](https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Hans-Jelitto/publication/359688325/figure/fig3/AS:1140400983150592@1648904190182/Alignment-of-the-Giza-pyramids-with-data-measured-by-Sir-W-M-F-Petrie-6-distances.png)