Decimal Watch by Robert Robin 1793. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Decimal Watch by Robert Robin 1793. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

If you take a close look at the watch shown above, you will begin to notice some oddities. This is a precision watch with decimal hours and seconds by Robert Robin from 1793. In this system there are 100 seconds in a minute and 100 minutes in an hour. Decimal time is the representation of the time of day using units which are decimally related. This term is often used to refer specifically to French Revolutionary Time.

|

10 metric hours in a day |

In 1788, Claude Boniface Collignon proposed dividing the day into 10 hours or 1000 minutes, each new hour into 100 minutes, each new minute into 1000 seconds, and each new second into 1000 tierces. The distance the sun travels in one new tierce at the equator, which is one-billionth of the circumference of the earth, would be a new unit of length, provisionally called a half-handbreadth, equal to four modern centimeters. Further, the new tierce would be divided into 1000 quatierces, which he called “microscopic points of time”. He also suggested a week of 10 days and dividing the year into 10 “solar months”. The final French Republican Calendar was introduced in 1793 with 30 days in a month and 12 months/ 360 days in a year, using a decimal timescale, adding 5 days of festivities at the end of the year. The Republican Calendar was not a success and lasted only from 1793 until 1805.

Decimal Watch by George Auziere 1795. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Decimal Watch by George Auziere 1795. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

This watch by George Auziere from 1795 shows three 10 day weeks (décades) and 30 days in a month. This particular watch also has the traditional 12 hour day and 60 minute hour for reference. You can tell it was actually used by the scratches on the watch crystal. Décades were abandoned in April of 1802 (Floréal an X).

Decimal Watch by André Féron 1795. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Decimal Watch by André Féron 1795. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

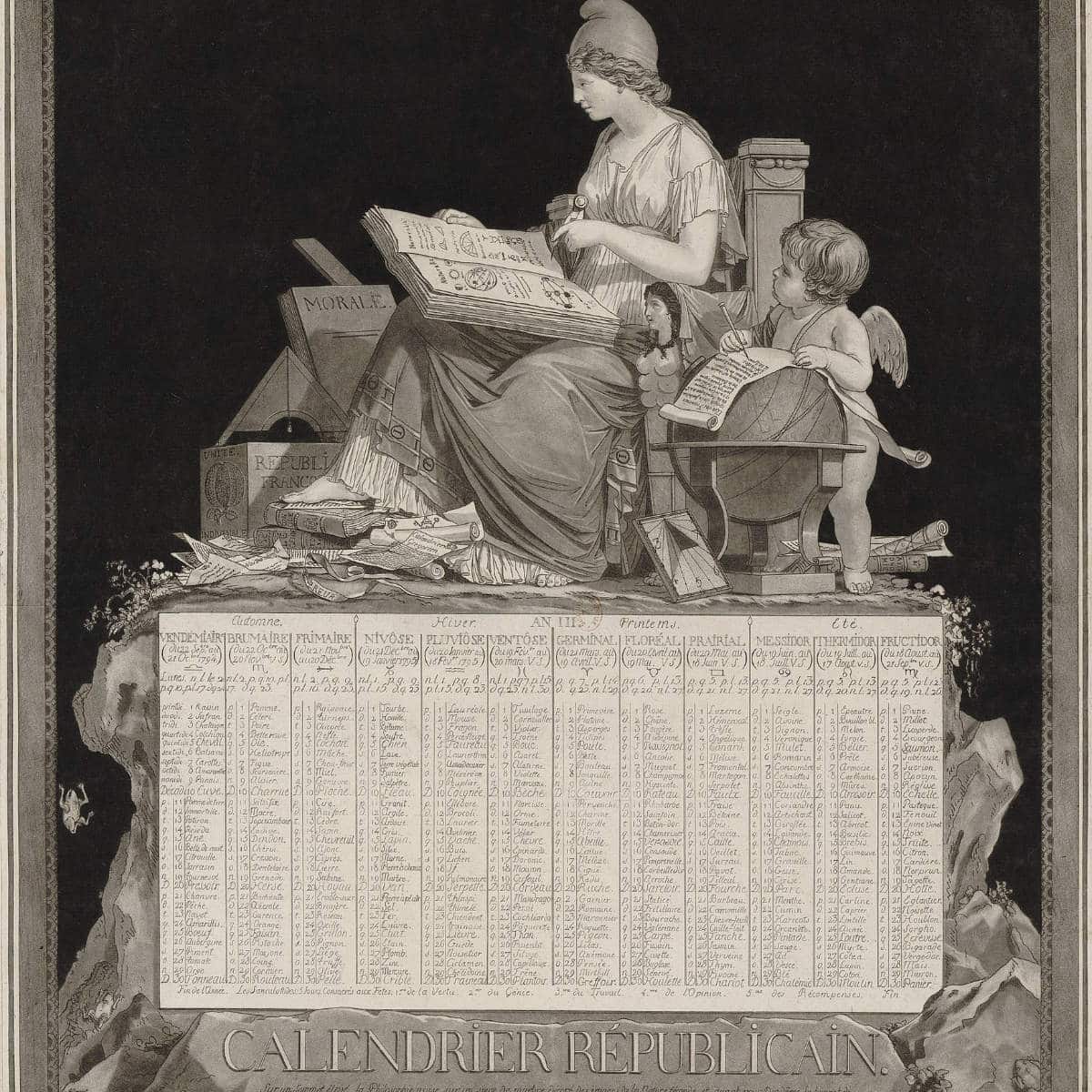

This watch by André Féron from 1795 shows the day of the month and the French Republican Calender. In France, it is known as the calendrier républicain as well as the calendrier révolutionnaire. Napoléon finally abolished the calendar with effect from 1 January 1806 (the day after 10 Nivôse an XIV), a little over twelve years after its introduction. The months were renamed in the French Republican calendar with descriptive names of the weather around Paris:

French Republican Calendar

French Republican Calendar

The Republican calendar year began at the Southward equinox. In the Northern Hemisphere the Southward equinox is known as the autumnal equinox. In the Southern Hemisphere it is known as the vernal or spring equinox. This meant that the new year began in autumn in Paris.

Decimal Watch from Neuchtel Arts and History Museum. Wikipedia

Decimal Watch from Neuchtel Arts and History Museum. Wikipedia

This unusual watch from the Neuchtel Arts and History museum has the imperial 12 hours and 60 seconds with French Republican Days on the outer rim. It also seems to incorporate the fixed 30 days per month. I don’t really see how it works since there are only two hands. Official use of decimal time began in the Republican year III, September 22, 1794, and mandatory use was suspended on April 7, 1795 (18 Germinal of the Year III), in the same law which introduced the original metric system. Since the Revolutionary Calendar lasted until 1805, we can give an approximate date for this watch.

French Decimal Watch from Pierre Basile LePaute. Wikipedia

French Decimal Watch from Pierre Basile LePaute. Wikipedia

This watch from Pierre Basile LePaute from Paris, son of Jean André LePaute, shows French decimal time and two sets of 12 Roman numerals. It also has a hand for the 30 days of the month. I cannot tell if the seconds hand counts decimal seconds but the end of the hand suggests it does. A decimal second is .864 of a normal (60 second per minute) second. Similarly, the minutes hand measures decimal minutes, 1.44 of a normal (60 minutes per hour) minute. The hours hand is double ended to read either decimal or 12 hour/day hours since there are 10 decimal hours and 24 normal hours in a day, or one revolution. This watch is a little confusing to read.

Decimal Watch from 1793. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Decimal Watch from 1793. Musée des Arts et Métiers, Paris

Here is another watch with a double ended hour hand from 1793 with the same principle described above. Even more confusing to read.

The metric system was conceived by a group of scientists to resolve troubling differences in weights and measures between countries. Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier (see my post), who is known as the “father of modern analytical chemistry”, was commissioned by the Assemblée nationale and Louis XVI of France to create a unified and rational system of measures. On December 10, 1799, a month after Napoleon’s coup d’état, the metric system was definitively adopted in France. The initial five units of the metric system dealt with length, area, volume of a solid (firewood specifically), volume of a liquid, and mass. The gram was the mass of a cubic centimeter of water. The meter was defined as a ten millionth the length of the distance between the North Pole and the Equator.

The 11th General Conference on Weights and Measures (1960) adopted the name Système International d’Unités (International System of Units, international abbreviation SI), for the recommended practical system of units of measurement.The “SI” is founded on seven units, from which all other units are derived. They are the meter, kilogram, second, ampere, kelvin, mole and candela. The second is currently defined as “the duration of 9 192 631 770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium 133 atom.”

Cafe Press Decimal Clock

Cafe Press Decimal Clock

For about $20 you can buy a decimal clock just like the one seen on the “Simpsons” and like the ones shown above (see references below). The sexagesimal system, which originated with the Sumerians and Babylonians, divides an hour into sixty minutes and minutes into sixty seconds. The word “minute” comes from the Latin pars minuta prima, meaning first small part, and “second” from pars minuta secunda or second small part. In angular measure, it is the degree that is subdivided into minutes and seconds, while in time, it is the hour.

References:

Watch and Clock Collector: http://www.nawcc-index.net/

Metric Time Links: http://zapatopi.net/metrictime/link.html

Lyle Zapatopi’s Metric Time: http://zapatopi.net/metrictime/

Metric Java Clock: http://minkukel.com/scripts/metric-clock/

Cafe Press Digital Wall Clocks: http://www.cafepress.com/+metric-time+clocks

Clock in the French Republican Calendar, courtesy of

Clock in the French Republican Calendar, courtesy of  Statue dedicated to the Revolution at the

Statue dedicated to the Revolution at the