Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 14 de 14

Siguiente

Anterior

2 a 14 de 14

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

|

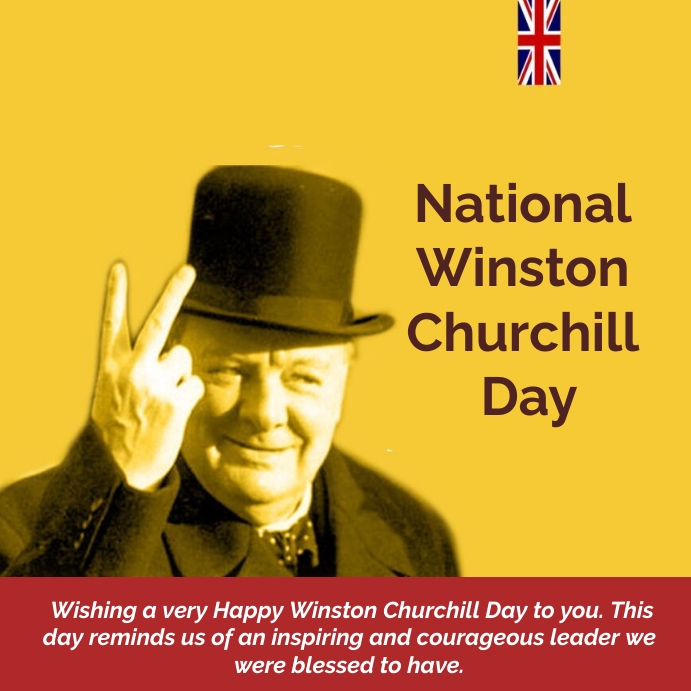

V For Victory – the sign which Churchill appropriated from the Belgians

We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis. We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis.

Resistance graffiti on a road in Norway the V sign cradeling the initials of King Haakon VII

Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war. Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war.

Soon after Churchill’s broadcast Douglas Ritchie at the BBC noticed that the Morse code for V was three dots and a dash ( …_ ) which was the same as the rhythm for the opening of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, and the BBC used it in its foreign language programmes directed at occupied Europe for the rest of the war. It was not long before the rhythm was used as a symbol of defiance in Europe, one which people could tap out almost anywhere.

In Germany Goebbels, the Nazi Propaganda Minister, was infuriated by the ‘V campaign’, but there was nothing he could do to stop it. He tried to argue that because ‘V’ was the first letter of the German word ‘viktoria’ and the musical representation was from a symphony written by a German composer then it was really a symbol in support of the Nazi’s final victory and was a sign of the conquered population’s support of Hitler, but of course no one believed him. To try to bury the use of the symbol by the resistance the Germans started using the ‘V’ themselves, even the Eiffel tower had a ‘V’ with the slogan ‘Germany is Victorious on All Fronts’ underneath.

TheEeiffel Tower during the German occupation of France TheEeiffel Tower during the German occupation of France

When Churchill first used the ‘V’ sign he sometimes did it with palm facing in until it was pointed out to him that this had a rather rude meaning for the working classes; from then on Churchill made a point of holding his hand palm outwards. Of course, the sign appealed to many people precisely because of its ‘double entendre’ meaning – with a simple movement of the wrist they could indicate a belief in victory and also tell Hitler where to go!

America also took the ‘V’ sign to heart and it appeared in numerous places, including on this poster from the War Production Board.

Four years after de Laveleye first urged the use of the ‘V’ sign the Allies finally achieved Victory in Europe, and months later came Victory against Japan, but by that time the iconic Second World War symbol of defiance had become so embedded in the minds of the people that it is still used today.

The ground crew of a Lancaster bomber return the ‘V for Victory’ sign projected into the sky by a neighbouring searchlight crew on VE Day.

There are some interesting pictures of the use of the ’V’ sign during the Second World War in this video

https://dorindabalchin.com/2019/02/16/v-for-victory-the-sign-which-churchill-appropriated-from-the-belgians/ |

|

|

|

|

| Enviado: 21/10/2024 10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Enviado: 21/10/2024 10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Para otros usos de este término, véase Austerlitz.

|

|

|

|

|

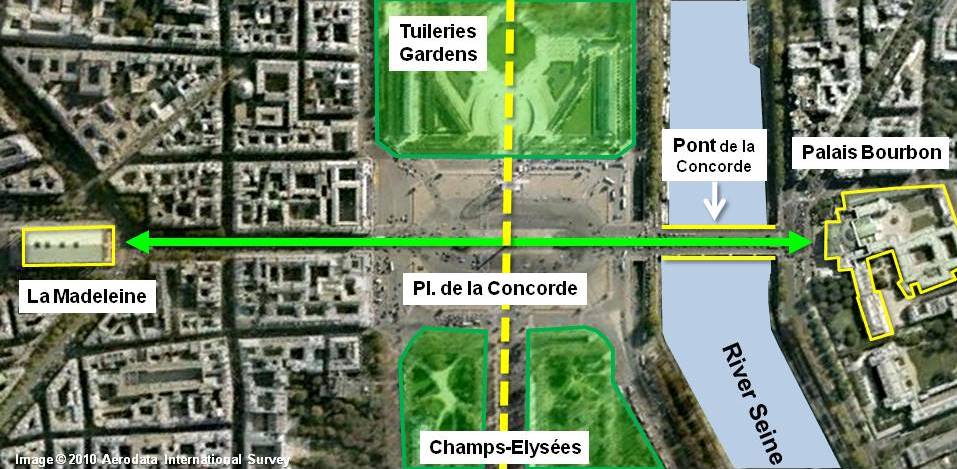

Llama de la Libertad (París)

La Llama de la Libertad, ofrecida al pueblo francés por donantes de todo el mundo como símbolo de la amistad franco-americana, en la plaza Diana (París).

La Llama de la Libertad (en francés, Flamme de la Liberté) de París es una réplica del mismo tamaño de la nueva llama situada en el extremo de la antorcha que lleva en la mano la Estatua de la Libertad de Nueva York desde 1986.1 El monumento, que tiene aproximadamente 3,5 metros de longitud, es una escultura de una llama de cobre dorado, apoyada en un pedestal de mármol gris y negro. Está situado cerca del extremo norte del puente del Alma, en la plaza Diana, en el distrito 8 de París, Francia.2

Fue ofrecida a la ciudad de París en 1989 por el International Herald Tribune en nombre de los donantes, que habían contribuido aproximadamente 400 000 dólares para su realización. Representaba la culminación de las celebraciones de 1987 del periódico por su cien aniversario de la publicación de un periódico en inglés en París. Más importante, la Llama era una muestra de agradecimiento por la restauración de la Estatua de la Libertad realizada tres años antes por dos empresas francesas que hicieron el trabajo artesanal del proyecto: Métalliers Champenois, que hizo el trabajo del bronce, y Gohard Studios, que aplicó el pan de oro. Aunque el regalo a Francia fue motivado por el centenario del periódico, la Llama de la Libertad es un símbolo más general de la amistad que une los dos países, igual que la Estatua de la Libertad cuando fue regalada a los Estados Unidos por Francia.

Este proyecto fue supervisado por el director de la unión de artesanos franceses en aquel momento, Jacques Graindorge. Propuso la instalación de la Llama de la Libertad en una plaza pública llamada Place des États-Unis en el distrito 16, pero el alcalde de París, Jacques Chirac, se opuso a esto. Tras un prolongado período de negociaciones, se decidió que la alama se situaría en una zona abierta cerca de la intersección de la Avenue de New-York y la Place de l'Alma. El monumento fue inaugurado el 10 de mayo de 1989 por Chirac.

En la base del monumento hay una placa conmemorativa que relata la siguiente historia:

"La Llama de la Libertad. Una réplica exacta de la llama de la Estatua de la Libertad ofrecida al pueblo de Francia por donantes de todo el mundo como símbolo de la amistad franco-americana. Con ocasión del centenario del International Herald Tribune, París 1887-1987."

La llama se convirtió en un monumento no oficial de Diana de Gales después de su muerte en 1997 en el túnel bajo el Pont de l'Alma.3 La llama es una atracción para turistas y seguidores de Diana, quiens pegan pósteres y folletos con material conmemorativo en la base. El antropólogo Guy Lesoeurs dijo que "la mayoría de las personas que vienen aquí piensan que se construyó para ella."2 La plaza del monumento se llama desde entonces Plaza Diana (París).

El monumento está cerca de la estación del Metro de París llamada Alma-Marceau en la línea 9 y de la estación Pont de l’Alma Línea 'C' del RER, así como por los buses número 42, 63, 72, 80, 92, y los autobuses turísticos Balabus.

El 14 de junio de 2008 se inauguró una nueva Llama de la Libertad, una escultura de Jean Cardot, que también simboliza las relaciones cálidas y respetuosas entre Francia y los Estados Unidos. Fue instalada en los jardines de la Embajada de los Estados Unidos en Francia en la Place de la Concorde, y se inauguró en presencia del Presidente de la República Francesa, Nicolas Sarkozy, y el Presidente de los Estados Unidos, George W. Bush. Esta nueva llama es la realización de un impulso compartido por el empresario francés Marc Ladreit de Lacharrière, y el embajador estadounidense Craig Roberts Stapleton, y tiene dos inscripciones, una del francés Marqués de La Fayette y otra del estadista americano Benjamin Franklin.

|

|

|

|

|

Male and Female symbols

Male symbol, Mars, blade

Military patches

Female symbol, Venus, chalice

|

|

|

Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 14 de 14

Siguiente

Anterior

2 a 14 de 14

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis.

We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis. Resistance graffiti on a road in Norway the V sign cradeling the initials of King Haakon VII

Resistance graffiti on a road in Norway the V sign cradeling the initials of King Haakon VII

Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war.

Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war. TheEeiffel Tower during the German occupation of France

TheEeiffel Tower during the German occupation of France

The ground crew of a Lancaster bomber return the ‘V for Victory’ sign projected into the sky by a neighbouring searchlight crew on VE Day.

The ground crew of a Lancaster bomber return the ‘V for Victory’ sign projected into the sky by a neighbouring searchlight crew on VE Day.

![Freemason Winston Churchill: A Life of Controversies and Leadership [5 Minute Recap] - YouTube](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/GtED39R74xs/hq720.jpg?sqp=-oaymwE7CK4FEIIDSFryq4qpAy0IARUAAAAAGAElAADIQj0AgKJD8AEB-AH-CYAC0AWKAgwIABABGGUgWShWMA8=&rs=AOn4CLBDKQVYdoGc3CAjTQFsabds6CkqCQ)