Solar god theories

[edit]

According to Macrobius who cites Nigidius Figulus and Cicero, Janus and Jana (Diana) are a pair of divinities, worshipped as Apollo or the sun and moon, whence Janus received sacrifices before all the others, because through him is apparent the way of access to the desired deity.[51][52]

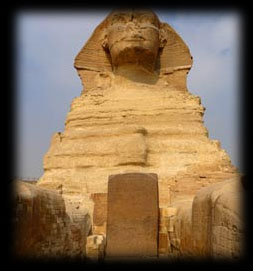

A similar solar interpretation has been offered by A. Audin who interprets the god as the issue of a long process of development, starting with the Sumeric cultures, from the two solar pillars located on the eastern side of temples, each of them marking the direction of the rising sun at the dates of the two solstices: the southeastern corresponding to the Winter and the northeastern to the Summer solstice. These two pillars would be at the origin of the theology of the divine twins, one of whom is mortal (related to the NE pillar, nearest the Northern region where the sun does not shine) and the other is immortal (related to the SE pillar and the Southern region where the sun always shines). Later these iconographic models evolved in the Middle East and Egypt into a single column representing two torsos and finally a single body with two heads looking at opposite directions.[53]

Numa, in his regulation of the Roman calendar, called the first month Januarius after Janus, according to tradition considered the highest divinity at the time.

The temple of Janus with closed doors, on a sestertius issued under Nero in 66 AD from the mint at Lugdunum

The temple of Janus with closed doors, on a sestertius issued under Nero in 66 AD from the mint at Lugdunum

Numa built the Ianus geminus (also Janus Bifrons, Janus Quirinus or Portae Belli), a passage ritually opened at times of war, and shut again when Roman arms rested.[54] It formed a walled enclosure with gates at each end, situated between the old Roman Forum and that of Julius Caesar, which had been consecrated by Numa Pompilius himself. About the exact location and aspect of the temple there has been much debate among scholars.[55] In wartime the gates of the Janus were opened, and in its interior sacrifices and vaticinia were held, to forecast the outcome of military deeds.[56] The doors were closed only during peacetime, an extremely rare event.[57] The function of the Ianus Geminus was supposed to be a sort of good omen: in time of peace it was said to close the wars within or to keep peace inside;[which?] in times of war it was said to be open to allow the return of the people on duty.[58]

A temple of Janus is said to have been consecrated by the consul Gaius Duilius in 260 BC after the Battle of Mylae in the Forum Holitorium. It contained a statue of the god with the right hand showing the number 300 and the left the number 65—i.e., the length in days of the solar year—and twelve altars, one for each month.[59]

The four-sided structure known as the Arch of Janus in the Forum Transitorium dates from the 1st century of the Christian era: according to common opinion it was built by the Emperor Domitian. However American scholars L. Ross Taylor and L. Adams Holland on the grounds of a passage of Statius[60] maintain that it was an earlier structure (tradition has it the Ianus Quadrifrons was brought to Rome from Falerii[61]) and that Domitian only surrounded it with his new forum.[62] In fact the building of the Forum Transitorium was completed and inaugurated by Nerva in AD 96.

Another way of investigating the complex nature of Janus is by systematically analysing his cultic epithets: religious documents may preserve a notion of a deity's theology more accurately than other literary sources.

The main sources of Janus's cult epithets are the fragments of the Carmen Saliare preserved by Varro in his work De Lingua Latina, a list preserved in a passage of Macrobius's Saturnalia (I 9, 15–16), another in a passage of Johannes Lydus's De Mensibus (IV 1), a list in Cedrenus's Historiarum Compendium (I p. 295 7 Bonn), partly dependent on Lydus's, and one in Servius Honoratus's commentary to the Aeneis (VII 610).[63] Literary works also preserve some of Janus's cult epithets, such as Ovid's long passage of the Fasti devoted to Janus at the beginning of Book I (89–293), Tertullian, Augustine and Arnobius.

As may be expected the opening verses of the Carmen,[64] are devoted to honouring Janus, thence were named versus ianuli.[65] Paul the Deacon[66] mentions the versus ianuli, iovii, iunonii, minervii. Only part of the versus ianuli and two of the iovii are preserved.

The manuscript has:

- (paragraph 26): "cozeulodorieso. omia ũo adpatula coemisse./ ian cusianes duonus ceruses. dun; ianusue uet põmelios eum recum";

- (paragraph 27): "diuum êpta cante diuum deo supplicante." "ianitos".

Many reconstructions have been proposed:[67] they vary widely in dubious points and are all tentative, nonetheless one can identify with certainty some epithets:

- Cozeiuod[68] orieso.[69] Omnia vortitod[70] Patulti; oenus es

- iancus (or ianeus), Iane, es, duonus Cerus es, duonus Ianus.

- Veniet potissimum melios eum recum.

- Diuum eum patrem (or partem) cante, diuum deo supplicate.

- ianitos.[71]

The epithets that can be identified are:

- Cozeuios

- i.e. Conseuius the Sower, which opens the carmen and is attested as an old form of Consivius in Tertullian;[72]

- Patultius

- the Opener;

- Iancus or Ianeus

- the Gatekeeper;

- Duonus Cerus

- the Good Creator;

- rex

- king (potissimum melios eum recum – the most powerful and best of kings);

- diuum patrem (partem)

- [73] father of the gods (or part of the gods);

- diuum deus

- god of the gods;

- ianitos

- keeping track of time, Gatekeeper.

The above-mentioned sources give: Ianus Geminus, I. Pater, I. Iunonius, I. Consivius, I. Quirinus, I. Patulcius and Clusivius (Macrobius above I 9, 15): Ι. Κονσίβιον, Ι. Κήνουλον, Ι. Κιβουλλιον, I. Πατρίκιον, I. Κλουσίβιον, I. Ιουνώνιον, I. Κυρινον, I. Πατούλκιον, I. Κλούσιον, I. Κουριάτιον (Lydus above IV 1); I. Κιβούλλιον, I. Κυρινον, I. Κονσαιον, I. Πατρίκιον (Cedrenus Historiarum Compendium I p. 295 7 Bonn); I. Clusiuius, I. Patulcius, I. Iunonius, I. Quirinus (Servius Aen. VII 610).

Even though the lists overlap to a certain extent (five epithets are common to Macrobius's and Lydus's list), the explanations of the epithets differ remarkably. Macrobius's list and explanation are probably based directly on Cornelius Labeo's work, as he cites this author often in his Saturnalia, as when he gives a list of Maia's cult epithets[74] and mentions one of his works, Fasti.[75] In relating Janus' epithets Macrobius states: "We invoke in the sacred rites". Labeo himself, as it is stated in the passage on Maia, read them in the lists of indigitamenta of the libri pontificum. On the other hand, Lydus's authority cannot have consulted these documents precisely because he offers different (and sometimes bizarre) explanations for the common epithets: it seems likely he received a list with no interpretations appended and his interpretations are only his own.[76]

https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/10/back-to-the-future-ii-queen-diana

https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2015/10/back-to-the-future-ii-queen-diana