|

|

General: SUIZA, UN ESTADO DE ORIGEN TEMPLARIO

إختار ملف آخر للرسائل |

|

جواب |

رسائل 1 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 34 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 35 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

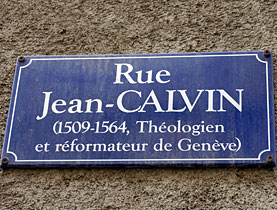

Las raíces calvinistas del secreto bancario

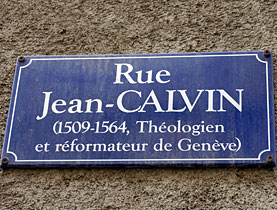

En Ginebra Calvino dejó sus huella no sólo en sus calles sino también en el espíritu de la ciudad. RDB En Ginebra Calvino dejó sus huella no sólo en sus calles sino también en el espíritu de la ciudad. RDB

Calvino continúa estando muy presente en la vida suiza en el inicio del siglo XXI y, especialmente, respecto a la cuestión del secreto bancario. El reformador, del que se celebra este viernes el 500 aniversario de su nacimiento, fue la fuente de la emancipación ciudadana.

Este contenido fue publicado en10 julio 2009 - 08:23

7 minutos

Xavier Comtesse, de Avenir Suisse, recuerda esta herencia. Entrevista.

El predicador no sólo fue un gran renovador de la sociedad. También dejó en Suiza y en el mundo una manera de pensar que impregna, todavía hoy en día, al mundo occidental. Lo que hay en la forma moderna de comprender a Dios o respecto al dinero, sean banqueros o no, o incluso en nuestra comprensión moderna de las instituciones y de la democracia: Calvino ha marcado todos estos campos.

swissinfo.ch: ¿En qué se basa el protestantismo de Calvino?

Xavier Comtesse: Calvino basó su pensamiento en que la Biblia tal y como está formulada en el lenguaje del pueblo, en la separación entre el Estado y la religión y sobre el acuerdo según el cual los creyentes, que financian la comuna, pueden elegir a los sacerdotes.

Esta forma de organización típicamente calvinista además, con el tiempo, se extendió a otros ámbitos no religiosos de la mentalidad helvética. Los representantes del Estado deben permanecer alejados de todas las instituciones religiosas y la ciudadanía participa en las decisiones políticas a todos los niveles, de la comuna al gobierno del país.

Estos dos elementos han llevado a una emancipación del pueblo, a su “otorgamiento de poderes”, como se dice hoy en día, el acceso a una forma de poder.

swissinfo.ch : ¿Y qué hubiera sido Suiza sin Calvino?

X.C.: Sin esta emancipación de la gente realizada por Calvino, creo que simplemente no tendríamos nada de democracia directa. Seríamos una República, como nuestros vecinos. Aunque aquí hay que citar también a Lutero que desempeñó en la Suiza de habla alemana el mismo papel que Calvino.

Este traslado de estructuras de la organización comunal hasta el nivel más alto del Estado es típico de Suiza.

swissinfo.ch : ¿Fue Ginebra más importante que Zúrich en esta materia?

X.C.: La suiza francófona no existía en ese momento. Ginebra era la ciudad que brillaba más de todo el país. Basilea también tenía importancia, pero este no era el caso de Zúrich, de Berna o de Lausana.

Esto es lo que explica que Calvino tuviera una fama internacional más grande que Lutero. Además después de Napoleón, Zúrich tenía menos habitantes que Ginebra y su economía era también menos importante.

swissinfo.ch: ¿Qué huellas dejó Calvino en el protestantismo?

X.C.: Conozco especialmente el caso de los Estados Unidos. El calvinismo es un pensamiento muy extendido. Cerca de 15 millones de personas son calvinistas. En los países anglosajones, se les llama presbiterianos.

Otras comunidades viven en Escocia y en Corea del Sur. Se calcula que existen 50 millones de presbiterianos en el mundo. Aunque en Suiza son sólo un puñado.

swissinfo.ch: ¿Cuáles fueron las relaciones de Calvino con la economía y con los bancos?

X.C.: Como reacción al comercio de indulgencias practicado por la Iglesia Católica para garantizar los ingresos del Vaticano, Calvino fue uno de los primeros dirigentes de la Iglesia en autorizar la concesión de créditos, pero con unas condiciones morales muy estrictas.

También levantó un puente hacia el presente. Los tipos de interés estaban fuera del debate, porque el crédito debía ser barato. Él trataba, como en la religión y la política, de proteger al ciudadano en el ámbito bancario imponiendo exigencias morales muy elevadas.

Además, uno de los principios del protestantismo es el de proteger la esfera privada. La combinación de este principio con el de la autorización de manejar los asuntos bancarios lleva directamente al secreto bancario.

swissinfo.ch: Pero históricamente el secreto bancario está considerado como un instrumento para proteger al ciudadano de las intrusiones del Estado en su esfera privada.

X.C.: Exactamente. Por ello la noción de secreto bancario da lugar a numerosos malentendidos. El nombre ‘secreto bancario’ conduce al error. Sería mejor hablar de ‘protección de la esfera privada por parte de la banca’.

Este tipo de protección no existe sólo en Suiza. En Francia por ejemplo, una esposa no tiene el derecho de informarse de las cuentas bancarias de su marido, que la ley considera como dependiente de la esfera privada.

En Suiza hemos ido un paso más adelante. La ley nos protege contra la arbitrariedad eventual del Estado. Por eso nos topamos con Calvino, ya que él elaboró este principio para proteger a los ciudadanos de la arbitrariedad de la poderosa Iglesia Católica.

swissinfo.ch: ¿Qué queda en la actualidad de esta ética calvinista, si se piensa en la crisis de los bancos y la plaza financiera?

X.C.: Esta crisis es una crisis de la moral. Deberíamos pues enfrentarnos más en el futuro al aspecto de la responsabilidad social. Se trataría de un tipo de un nuevo calvinismo, laico, con las señales morales pero no religiosas.

Lo podemos ver en las manifestaciones, por ejemplo, en el dominio del control de calidad. Los nuevos estándares ISO sirven para llenar los déficits en el campo de las responsabilidades.

La Organización Internacional de Normalización (ISO) tiene su sede en Ginebra, como tantas otras instituciones de influencia internacional. Eso también es una herencia de Calvino.

Otra ‘institución’ ginebrina es, nada menos, que Internet, que fue inventado en el CERN. Ahora bien Internet es calvinista ya que permite a la ciudadanía, a la población, al usuario, tener un acceso directo a la información.

Antes había que solicitar a los poderosos intermediarios para poder recibir estas informaciones. Internet rehace así el acceso a los mercados, de la misma manera que la reforma de Calvino había hecho posible un acceso directo a Dios.

swissinfo.ch: Alexander Künzle

(Adaptación: Iván Turmo)

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 36 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

Temple de la Madeleine Church - Geneva, Switzerland

Temple de la Madeleine Church - Geneva, Switzerland

Madeleine Church, Geneva, Switzerland. The Temple de la Madeleine Madeleine Church is located in the foot of the Old Town of Geneva, Switzerland

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 37 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 38 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

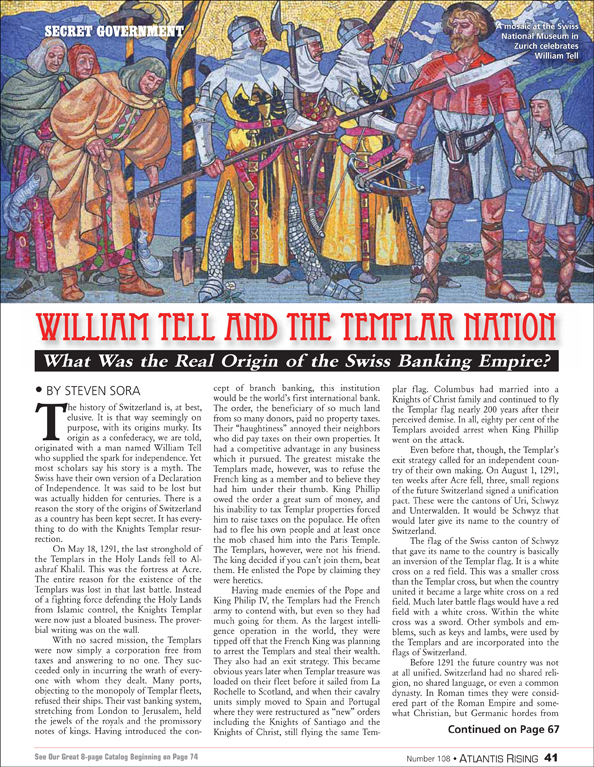

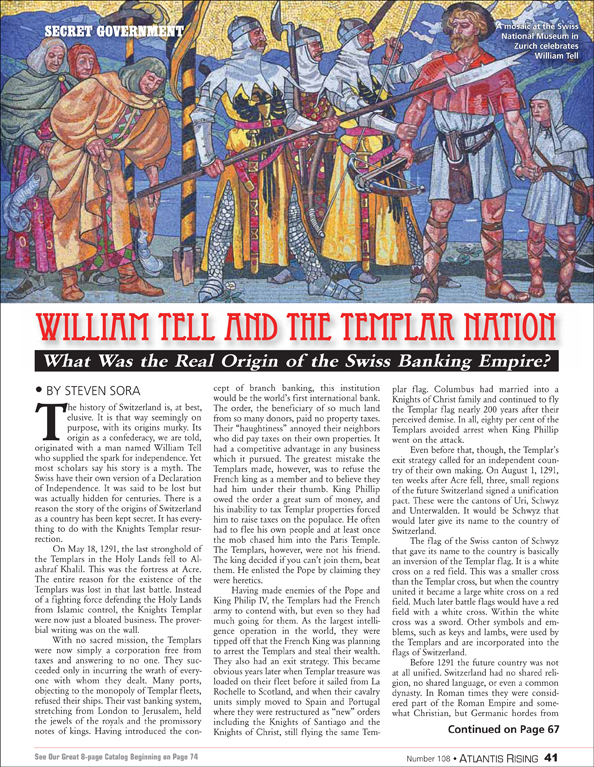

DID THE TEMPLARS REALLY GO OUT OF EXISTENCE?

The history of Switzerland is, at best, elusive. It is that way seemingly on purpose, with its origins murky. Its origin as a confederacy, we are told, originated with a man named William Tell who supplied the spark for independence. Yet most scholars say his story is a myth. The Swiss have their own version of a Declaration of Independence. It was said to be lost but was actually hidden for centuries. There is a reason the story of the origins of Switzerland as a country has been kept secret. It has everything to do with the Knights Templar resurrection.

On May 18, 1291, the last stronghold of the Templars in the Holy Lands fell to Al-ashraf Khalil. This was the fortress at Acre. The entire reason for the existence of the Templars was lost in that last battle. Instead of a fighting force defending the Holy Lands from Islamic control, the Knights Templar were now just a bloated business. The proverbial writing was on the wall.

With no sacred mission, the Templars were now simply a corporation free from taxes and answering to no one. They succeeded only in incurring the wrath of everyone with whom they dealt. Many ports, objecting to the monopoly of Templar fleets, refused their ships. Their vast banking system, stretching from London to Jerusalem, held the jewels of the royals and the promissory notes of kings. Having introduced the concept of branch banking, this institution would be the world’s first international bank. The order, the beneficiary of so much land from so many donors, paid no property taxes. Their “haughtiness” annoyed their neighbors who did pay taxes on their own properties. It had a competitive advantage in any business that it pursued. The greatest mistake the Templars made, however, was to refuse the French king as a member and to believe they had him under their thumb. King Phillip owed the order a great sum of money, and his inability to tax Templar properties forced him to raise taxes on the populace. He often had to flee his own people and at least once the mob chased him into the Paris Temple. The Templars, however, were not his friend. The king decided if you can’t join them, beat them. He enlisted the Pope by claiming they were heretics.

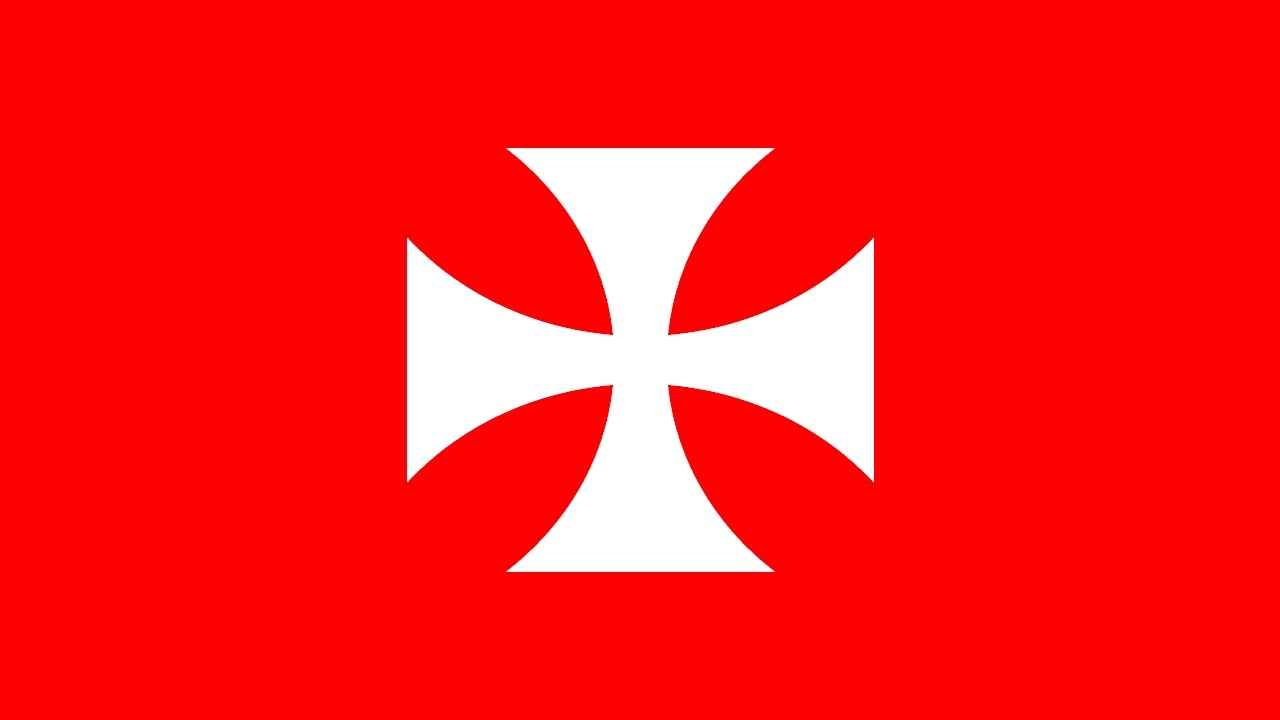

Having made enemies of the Pope and King Philip IV, the Templars had the French army to contend with, but even so they had much going for them. As the largest intelligence operation in the world, they were tipped off that the French King was planning to arrest the Templars and steal their wealth. They also had an exit strategy. This became obvious years later when Templar treasure was loaded on their fleet before it sailed from La Rochelle to Scotland, and when their cavalry units simply moved to Spain and Portugal where they were restructured as “new” orders including the Knights of Santiago and the Knights of Christ, still flying the same Templar flag. Columbus had married into a Knights of Christ family and continued to fly the Templar flag nearly 200 years after their perceived demise. In all, eighty percent of the Templars avoided arrest when King Phillip went on the attack.

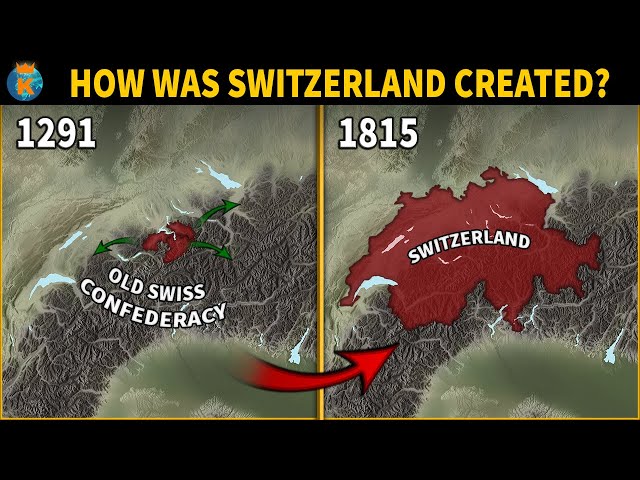

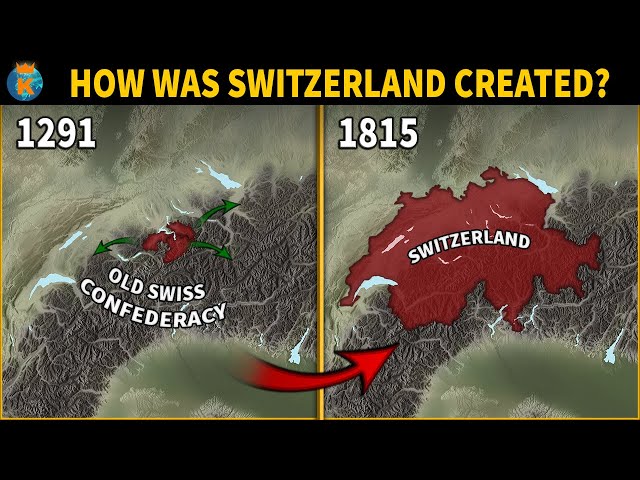

Even before that, though, the Templar’s exit strategy called for an independent country of their own making. On August 1, 1291, ten weeks after Acre fell, three, small regions of the future Switzerland signed a unification pact. These were the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. It would be Schwyz that would later give its name to the country of Switzerland.

The flag of the Swiss canton of Schwyz that gave its name to the country is basically an inversion of the Templar flag. It is a white cross on a red field. This was a smaller cross than the Templar cross, but when the country united, it became a large white cross on a red field. Much later, battle flags would have a red field with a white cross. Within the white cross was a sword. Other symbols and emblems, such as keys and lambs, were used by the Templars and are incorporated into the flags of Switzerland.

Before 1291, the future country was not at all unified. Switzerland had no shared religion, no shared language, or even a common dynasty. In Roman times they were considered part of the Roman Empire and somewhat Christian, but Germanic hordes from the north brought pagan religion and Germanic language.

As Rome imploded, the territory that would become Switzerland was under a handful of minor family dynasties that mostly came apart. Circa 1300, no one expected the small towns and thinly settled valleys to unite or form cantons or states. The Holy Roman Empire decided these were its property but asked only for taxes. Modern historians concur there was no such thing as Swiss, or Switzerland, before 1400.

Birth of the Templar Nation

That changed in 1291 when a document known as the Bundesbrief united Uri Schwyz and Unterwalden. Representatives would convene at a mountain meadow on Lake Lucerne. The forest cantons, as they were known, would sign a compact of mutual assistance. Folktales record the white-coated, red-crossed knights that pledged assistance to the Swiss Confederacy as it would be known. The document itself was like the American Declaration of Independence, and while it might be expected to have been regarded as sacred; it wasn’t. Instead it was simply lost until the nineteenth century. Or at least kept secret. Then when the expected assault on the Templar existence finally came the Templars were ready.

On Oct 13, 1307, the command went out to arrest the Knights Templar. That day and in the weeks to follow, 600 out of 3000 knights in France were arrested. These were just knights. Each had a retinue of squires, servants, and aides who were not arrested. So, the Templar organization still had thousands who were not apprehended. Some had been traveling regularly through the Alps to Switzerland, which had once been a province of the Merovingian kings and where the small city of Sion once held the Merovingian mint.

Swiss Alpine passes and its central location brought trade through the country and allowed craftsmen access to markets outside of their country. Trade fairs and markets from these times always had compliant bankers and moneylenders who would assist merchants. Similarities between the Templar invention of international banking and Switzerland’s leading role in banking today are no coincidence.

Just how many Templar knights entered Switzerland would not be known. The Hapsburg family “controlled” Swiss cantons and did not allow anyone to challenge their ability to tax the cantons. They allowed the cantons to rule themselves in law and custom as long as they paid their taxes. The Templars, however, had existed for nearly 200 years without paying taxes. Unfortunately, the Swiss, noted for their secrecy, either know little of their early history or deliberately claim not to know.

William Tell and Swiss Independence

The story of William Tell may be a cover tale for the new challenge to the Hapsburg establishment. It is said to be a myth, but unlike myths that begin with nebulous timeframes, the William Tell story begins with an exact date. On November 18, 1307, William Tell visited the town of Altdorf with his son. This was five weeks after the Templars fled France ahead of their arrests. Altdorf was a municipality of Uri, one of the first three cantons to unite shortly after the Templar loss of Acre. He met with and offended Albrecht Gessler, who is the “Vogt,” a nominal bureaucrat appointed by the Habsburgs. The Vogt had hung his hat in the center of town and declared everyone who passed the hat had to bow to it. Tell passed by and publicly refused to bow. Gessler wanted to arrest the stranger but instead challenged him to shoot an apple off his son’s head with an arrow. Tell accomplished the dangerous challenge and Gessler commented that he still held another arrow. Tell’s answer was that it was for killing Gessler if he missed. The outcome was that Tell killed Gessler. His arrow struck a blow for liberty igniting the cantons against their Hapsburg overlords. Tell played a leading role in the rebellion that followed. In 1307–1308 many forts of the Hapsburgs were destroyed and this, in effect, united others and finally brought about the Swiss Confederation. Tell himself was declared the “first confederate” in a song of his exploits.

The Scots Guard and the Swiss Guard

Possibly the largest contingent of fleeing Templars went into the welcoming arms of Scotland. In Scotland, Robert Bruce had challenged the power of the King of England and declared Scotland’s independence. The English army would ride north and meet the Scots at Bannockburn. Just as it appeared the Scots were beaten, a fresh force of Templar Knights rode into battle and turned the tide. It was June 24, 1314, the feast of St. John Baptist, a most sacred day to the Templars. Soon afterwards the Scots Guard became a military force for hire.

In Switzerland, the Swiss cantons decided not to pay the feudal taxes imposed on them. The Hapsburg dukes were not simply going away though. In 1315, just one year after Bannockburn, the dukes sent an army to enforce the feudal dues. As with the English invasion of Scotland, the Hapsburgs thought the tiny cantons had no chance of resisting their army. But, like the English at Bannockburn, the Hapsburgs were not ready for the army they faced. In the Pass of Morgarten, the infantry of Uri and Schwyz defeated the Austrian cavalry in what became known as “the Marathon of Switzerland.” Like the Scottish victory at Bannockburn, the Swiss fought and defeated a larger enemy. No doubt incorporating ex-Templars as well as their training and support, the Swiss would form the Swiss Guard. It was also a mercenary force that could be leased out only with the approval of the Guard, not by the whims of a king. Ironically the Swiss Guard would be hired to defend the Vatican.

The Pontifical Swiss Guard had their origins in the fifteenth century when Pope Sixtus IV made an alliance with the Swiss Confederation. History shows their independence in not always fighting for one country. They fought for France against Naples, and both for and against the Holy Roman Empire. Their bravery, however, was never in question. Like the Templars, they never fled from greater odds. On May 6, 1527, 189 Swiss Guards fought a rear-guard action against the Holy Roman Empire. While 40 guard members helped Pope Clement VII escape, 147 of the 189 died, including their commander.

The Swiss Confederation grew with the addition of Zurich, Bern, Lucerne and Zug. While it had a strong fighting force, it declared its neutrality. It would take another two centuries to complete the formation of what became Switzerland. By becoming a neutral nation they were possibly protecting themselves from the Catholic France and Catholic Austria to the west and east. They were not always neutral, however, and had taken Lugano and other Italian properties while Italy was still a disrupted state. Oddly enough, in a very Protestant country, the Swiss Guard is made up of Swiss male citizens who are trained in the Swiss military and practice the Catholic religion.

It is no coincidence that the modern Red Cross also was born in Switzerland. The battle of Solferino was fought on June 24 of 1857. Like Bannockburn this was the Feast of St. John the Baptist. The story goes that a young man by the name of Henri Jean Dunant came to survey the damage. He later produced a book on the battlefield and presented it to wealthy and prominent citizens to create an international organization of relief workers. Switzerland at this time was a Confederation of 22 cantons and 3000 communes. Its neutrality was reiterated and protected by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 and confirmed by the Treaty of Vienna in 1815. Five of the prominent men met and agreed to call for a larger meeting. Prince Heinrich XIII of Reuss represented the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and became Vice President. Impressed by the St. John connection, delegates came from around the world. The HQ was at Basle. Rooms were taken in a chapel owned by the Teutonic knights.

The Country the Templars Created

Modern Switzerland has been built on banking, bank secrecy, precision engineering and pharmaceuticals. Finance is the central pillar of the Swiss economy. While bank secrecy is on the defense from the prying IRS, over five trillion dollars of “cross-border” wealth is known to be managed in Switzerland. Like the Templar bank of centuries before, the banks of Switzerland cater to national rulers, who often treat their nation’s riches as their own. The Swiss banks in turn have been accused of treating the money deposited as belonging to them. When President Mobutu of Zaire died in exile in 1997, Swiss newspapers reported he had $5 billion deposited in their banks. Swiss banks returned $8 million.

Templar scientific studies, once dubbed alchemy, are mirrored in the dominance of Swiss chemical and pharmaceutical companies. BASF, Zeochem, Novartis, and Hoffman-L Roche are Swiss companies with an international customer base.

Finally, the Templars and their sister order of St. Bernard the Cistercians, were known for their engineering abilities. Today the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator sits inside the Swiss border with France. This is CERN. Most Americans heard of it only through Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons when his character Robert Langdon discovers CERN technology is going to be used to destroy the Vatican. (Other conspiracy theorists worry CERN could destroy the planet.) It should be noted it was a CERN scientist, not Al Gore, who invented the World Wide Web in 1989.

The Templar order that the French King and the Pope forced into hiding, remains alive, and hiding in plain sight, in Switzerland, the center of Europe.

https://steemit.com/history/@conspiracyhq/william-tell-and-the-templar-nation |

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 39 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

Swiss history before 1914

In 1499 the Swiss gained independence from the Holy Roman Emperor and expanded their territory by invading nearby areas. Around this time, Swiss mercenaries were the most sought after and feared troops in Europe. But in 1515 they were defeated by combined French and Venetian forces at the battle of Marignano. Realising that they could not compete against larger states, the Swiss stopped trying to expand and declared neutrality. Later that century, the Reformation led to religious divides within the country, but the Swiss remained neutral during the resulting religious warfare in Europe. The French invaded Switzerland in 1798 and created a puppet state. After the defeat of Napoleon, however, Switzerland’s “perpetual neutrality” was guaranteed by international treaty.

Above: A Swiss postcard from the First World War period. It associates the soldiers of the day (right) with citizens of 1291 who created the Swiss federal charter of that year, which formed the origins of modern-day Switzerland. Other patriotic postcards from the time referred to the Swiss folk hero William Tell.

Before considering the First World War period, it is worth quickly summarising earlier Swiss history. The area that is now Switzerland came under Roman rule, and then that of the Holy Roman Empire (which also covered much of the rest of central Europe, from modern Germany down to northern Italy). In 1291, some Swiss regions united against the Holy Roman Empire, forming a defence league. Other cities and districts gradually joined the league, and this was the origin of the system of cantons: a loose confederation of administrative districts, comparable in some ways to US states, with no strong central government.

In 1848, a new federal constitution was drawn up, which formed the basis for modern Switzerland, recognising 22 (later 23) cantons and establishing the capital at Berne. During the second half of that century, Switzerland tried (not always successfully) to keep out of international politics as much as possible.

Above: A 1914 postcard marking the moment only 100 years before when Geneva had joined the rest of the Swiss confederation.

The country was actually relatively young in 1914. The traditional date for the founding of the Swiss state is 1291, but it has been argued that the state was really founded during and immediately after the Napoleonic Wars. That was when Switzerland became a republic, rather than a loose union of cantons, and gained the first significant numbers of French- and Italian-speaking inhabitants.

http://www.switzerland1914-1918.net/switzerland-before-1914.html

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 40 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 41 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

The historicity of William Tell has been subject to debate. François Guillimann, a statesman of Fribourg and later historian and advisor of the Habsburg Emperor Rudolf II, wrote to Melchior Goldast in 1607: "I followed popular belief by reporting certain details in my Swiss antiquities [published in 1598], but when I examine them closely the whole story seems to me to be pure fable."

In 1760, Simeon Uriel Freudenberger from Luzern anonymously published a tract arguing that the legend of Tell in all likelihood was based on the Danish saga of Palnatoki. A French translation of his book by Gottlieb Emanuel von Haller (Guillaume Tell, Fable danoise), published under Haller's name to protect Freudenberger, was burnt in Altdorf.[29]

The skeptical view of Tell's existence remained very unpopular, especially after the adoption of Tell as depicted in Schiller's 1804 play as national hero in the nascent Swiss patriotism of the Restoration and Regeneration period of the Swiss Confederation. In the 1840s, Joseph Eutych Kopp (1793–1866) published skeptical reviews of the folkloristic aspects of the foundational legends of the Old Confederacy, causing "polemical debates" both within and outside of academia.[30] De Capitani (2013) cites the controversy surrounding Kopp in the 1840s as the turning point after which doubts in Tell's historicity "could no longer be ignored".[31]

From the second half of the 19th century, it has been largely undisputed among historians that there is no contemporary (14th-century) evidence for Tell as a historical individual, let alone for the apple-shot story. Debate in the late 19th to 20th centuries mostly surrounded the extent of the "historical nucleus" in the chronistic traditions surrounding the early Confederacy.

The desire to defend the historicity of the Befreiungstradition ("liberation tradition") of Swiss history had a political component, as since the 17th century its celebration had become mostly confined to the Catholic cantons, so that the declaration of parts of the tradition as ahistorical was seen as an attack by the urban Protestant cantons on the rural Catholic cantons. The decision, taken in 1891, to make 1 August the Swiss National Day is to be seen in this context, an ostentative move away from the traditional Befreiungstradition and the celebration of the deed of Tell to the purely documentary evidence of the Federal Charter of 1291. In this context, Wilhelm Oechsli was commissioned by the federal government with publishing a "scientific account" of the foundational period of the Confederacy in order to defend the choice of 1291 over 1307 (the traditional date of Tell's deed and the Rütlischwur) as the foundational date of the Swiss state.[32] The canton of Uri, in defiant reaction to this decision taken at the federal level, erected the Tell Monument in Altdorf in 1895, with the date 1307 inscribed prominently on the base of the statue.

Later proposals for the identification of Tell as a historical individual, such as a 1986 publication deriving the name Tell from the placename Tellikon (modern Dällikon in the Canton of Zürich), are outside of the historiographical mainstream.[33]

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 42 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 43 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 44 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 45 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

On 8 May 1945, Swiss officials found only dried peas in the basement of the German embassy in Bern. There was no trace of the gold they were looking for.

Illustration: Marco Heer

Dried peas instead of gold bars

Shortly before the end of the war, Germany’s Foreign Office moved large quantities of gold from Berlin to the German legation in Bern. Just a few hours after Germany surrendered, the vaults were empty. The fruitless search for the Bern gold hoard began.

![Gabriel Heim]()

Gabriel Heim is a book and film author and exhibition organiser. He is principally concerned with research into topics of modern and contemporary history and lives in Basel.

At the request of the Political Department, the Federal Council passed a resolution on 8 May 1945:

In the light of recent global military and political events, the time has come when the Federal Council can say with certainty that an official imperial government no longer exists. […] The German missions in Switzerland are to be closed and their official premises and archives are to be given into the custody of a future legal successor to the imperial government, which is no longer recognised.

To enable the relevant officers to carry out this task as smoothly as possible in view of Germany’s surrender, the Federal Prosecutor’s office had issued a secret command the previous evening ordering that the premises of the German legation on Willadingweg and Elfenstrasse in Bern were to be taken over by the Political Department at 2 p.m. on 8 May and sealed under police protection. The subsequent cataloguing of the premises revealed that the German Reich’s final hours in Bern had been used to dispose of large quantities of paper in the building’s heating system, and to remove all trace of the strategic cache of gold and currency held in the vault. The inventory prepared by the Federal Prosecutor’s office reads matter-of-factly, after the metal cabinets were opened:

A box of household effects, a can of oil, another box, the contents of which are exclusively foodstuffs, tinned foods, etc., a carton of dried peas labelled: Ministerialdirektor Schroeder, Berlin W8, Auswärtiges Amt (Schroeder, Head of Department, Foreign Office, Berlin W8).

The end of World War II was celebrated with great rejoicing in Lausanne.

Keystone/STR

What remained, on the afternoon of 8 May, of all the years of diplomatic activity was the clean-swept result of weeks of precautionary measures to make incriminating material, decryption devices, cash and, above all, an exceptional amount of gold vanish. A telegram of 5 May from Federal Prosecutor Balsiger to the Bern cantonal police shows that all this hustle and bustle surrounding the legation did not go unnoticed:

Please note that if any attempt is made by Herr Minister Köcher or another diplomatic official to transport the gold away, police should not intervene. Instead – for information reasons – the vehicle should be traced and it should be determined where the gold is taken.

Even though there was no longer any impending threat of a letter of protest from Berlin, and the German diplomatic personnel in Switzerland, headed from 1937 to 1945 by Otto Carl Köcher, were mainly occupied with making arrangements for the time ‘afterwards’, Switzerland’s federal justice system didn’t drop its guard for one second in maintaining its observational role in the lead-up to ‘zero hour’. This attitude was also held at the highest echelons of the Confederation’s diplomatic corps, which stated in an internal note dating from late April:

Switzerland, which recognises the Hitler regime and maintains diplomatic relations with that regime, will be faced with a dilemma as to how to break off these diplomatic relations. However, it would hardly be desirable to cut ties with Hitler before the Allies declare the war in Europe to be over.

Köcher (left) was required to vacate the legation premises in Bern on 12 May 1945. He is escorted here by a Swiss agent.

Keystone/STR

So it was that during the night of 8 May 1945, a number of vehicle transports shuttled back and forth completely unchallenged between the German and Japanese embassies in Bern. But the ink was barely dry on the surrender agreement before the search began for the Bern gold hoard. At the centre of the investigations by the Federal Prosecutor’s office was the legation’s long-standing caretaker, Karl Höbenstreit:

‘Since the beginning of April I noticed that gold was being brought to the legation by car from Konstanz once or twice a week. The weight of the boxes varied between 20 and 30 kilograms. By my count, there would have been around 15 boxes. They were labelled: Absender – Auswärtiges Amt, Berlin (Sender – Foreign Office, Berlin).’

It was later suspected that these deliveries could have been part of the secret disposition fund arranged by the Berlin Foreign Office (Auswärtiges Amt), which Minister Köcher had had brought to safety using his official cars. But that wasn’t all. More gold found its way to the vaults at Willadingweg 78 by rail: ‘On Thursday, 19 April in the evening, a diplomatic pouch of around 1,500 kilograms arrived at Bern railway station,’ Höbenstreit stated. ‘The items were sacks containing crates filled with straw, with a small box of gold in the middle. The sacks were fastened with a lead seal. […] My job was merely to unpack the sacks and move the crates – without opening them – into the vault.’ When asked whether he knew where the gold had been taken to, the caretaker, who had been very busy during those days, responded: ‘No. I had a lot to do with burning files, so I didn’t always see what was brought to the vault, or taken away from it.’

Three years later, the investigators were no further forward. The witness accounts remained vague, or contradicted each other. Now, there was also talk of jewellery, and of a total value in excess of ten million Swiss francs – money that could have made it easier for prominent Nazis to disappear. Otto Carl Köcher – who, incidentally, had grown up in Basel – was detained by the Americans on 31 July 1945 as he attempted to leave Switzerland. They too were hunting for the gold from the Bern legation, because as a victorious power they had a claim to it. And Minister Köcher? He was interned in Ludwigsburg prison camp, and committed suicide on 27 December.

Until the very last moment, files were incinerated in the embassy’s basement boiler room. This photo by the Federal Prosecutor’s office shows the clean-up efforts after 8 May 1945.

Swiss Federal Archives

https://blog.nationalmuseum.ch/en/2020/04/berns-nazi-gold-hoard/ |

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 46 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

Nazi gold

Much of the focus of the discussion about Nazi gold (German: Raubgold, "stolen gold") concerns how much of it Nazi Germany transferred to overseas banks during World War II. The Nazis looted the assets of their victims (including those in concentration camps) to accumulate wealth. In 1998, a Swiss commission estimated that the Swiss National Bank held $440 million ($8 billion in 2020 currency) of Nazi gold, over half of which is believed to have been looted.

Some of the accumulated wealth was used to finance the war, but the total spending remains unclear. The present whereabouts of the gold has been the subject of several books, conspiracy theories, and a failed civil lawsuit brought in January 2000 against the Vatican Bank, the Franciscan Order, and other defendants.

Nazi gold stored in Merkers Salt Mine  As Minister of Economics, Walther Funk accelerated the pace of rearmament and as Reichsbank president banked for the Schutzstaffel the gold rings of Buchenwald victims

The draining of Germany's gold and foreign exchange reserves inhibited the acquisition of materiel, and the Nazi economy, focused on militarization, could not afford to deplete the means to procure foreign machinery and parts. Nonetheless, towards the end of the 1930s, Germany's foreign reserves were unsustainably low. By 1939, Germany had defaulted upon its foreign loans and most of its trade relied upon command economy barter.[1]

However, this tendency towards autarkic conservation of foreign reserves concealed a trend of expanding official reserves, which occurred through looting assets from annexed Austria, occupied Czechoslovakia, and Nazi-governed Danzig.[2] It is believed that these three sources boosted German official gold reserves by US$71 million ($1.3 billion in 2020 currency) between 1937 and 1939.[2] To mask the acquisition, the Reichsbank understated its official reserves in 1939 by $40m relative to the Bank of England's estimates.[2]

During the war, Nazi Germany continued the practice on a much larger scale. Germany expropriated some $550m in gold from foreign governments, including $223m from Belgium and $193m from the Netherlands.[2] These figures do not include gold and other instruments stolen from private citizens or companies. The total value of all assets allegedly stolen by Nazi Germany remains uncertain.

Advancing north from Frankfurt, the U.S. Third Army cut into the future Soviet zone when it occupied the western tip of Thuringia. On 4 April 1945 the 90th Infantry Division took Merkers, a few kilometres inside the border in Thuringia. On the morning of the 6th, two military policemen, Private First Class (PFC) Clyde Harmon and PFC Anthony Kline, enforcing the customary orders against civilian circulation during an evening curfew, stopped two women on a road outside Merkers. Since both were French displaced persons, with one of them pregnant attempting to find a doctor, the military policemen decided to bring them back to PFC Richard C. Mootz. Luckily for Mootz, he and the women had something in common: they could all speak German. While getting to know them better and escorting them back into the town, they passed the entrance to the Kaiseroda salt mine in Merkers.

The two women told Mootz[3] that the mine contained gold stored by the Germans, along with other treasures. Once back in his unit, he attempted to tell three other officers, but they weren't interested in listening. He called other military personnel; by noon, the story had passed on up to the chief of staff and the division's G-5 officer, Lt. Col. William A. Russell, who, in a few hours, had the news confirmed by other DPs and by a British sergeant who had been employed in the mine as a prisoner of war and had helped unload the gold. Russell also turned up an assistant director of the National Gallery in Berlin who admitted he was in Merkers to care for paintings stored in the mine.[4]

The next day was Sunday. In the morning, while Colonel Bernard D. Bernstein, Deputy Chief, Financial Branch, G-5, Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), read about the find[5] in the Stars and Stripes's Paris edition,[6][7] 90th Infantry Division engineers blasted a hole in the vault wall to reveal on the other side a room 23 metres (75 feet) wide and 46 m (151 ft) deep. They found 3,682 bags and cartons of German currency, 80 bags of foreign currency, 8,307 gold bars, 55 boxes of gold bullion, 3,326 bags of gold coins, 63 bags of silver, one bag of platinum bars, eight bags of gold rings and 207 bags and containers of Nazi loot that included valuable artwork.[8]

On Sunday afternoon, Bernstein, after verifying to the fullest the newspaper story with Lt Col R. Tupper Barrett, Chief, Financial Branch, G-5, 12th Army Group, flew to SHAEF Forward at Rheims where he spent the night, it being too late by then to fly into Germany. At noon on Monday, he arrived at General George S. Patton's Third Army Headquarters with instructions from Eisenhower to check the contents of the mine and arrange to have the treasure taken away. While he was there, orders arrived for him to locate a depository farther back in the SHAEF zone and supervise the moving. (Under the Big Three arrangements, the part of Germany containing Merkers would be taken over by the Soviets for military government control after the fighting ended.)[5] Bernstein and Barrett spent Tuesday looking for a site and finally settled on the Reichsbank building in Frankfurt.

According to a late-1990s study for the U.S. Department of State led by American diplomat and attorney Stuart E. Eizenstat, gold looted from occupied countries and stolen from individuals was transferred to the Swiss National Bank (SNB) to finance its war effort. Some gold was taken from Holocaust victims, though Eizenstat points out there is no evidence the SNB knew of this as the gold had been molded into bars.[9] A Swiss commission headed by historian and economist Jean-François Bergier estimated that the SNB received $440m ($8b 2020) in gold from Nazi sources, of which $316m ($5.8b in 2020) is estimated to have been looted.[9] Further, the Bergier commission found that the SNB's governing board knew at an early point that the gold was being looted from other countries.[9] The U.S. study further found that Germany transferred over $300m (2.6b 1998)—about $240m of which was looted—to neutral countries Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey (all of which aided Germany through non-military exchanges), mostly using the SNB.[9] Much of the gold was not recovered by the Allies, with only $18.5m of the looted $240m the neutral countries (excluding Switzerland) received in trade returned to the Tripartite Gold Commission; almost $15 million of this was from Sweden. That country separately provided about $66m of $100m provided by it, Argentina, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey, of about $480m sought for Europe overall.[9] Eizenstat notes that although there were Argentine sympathies to the Axis, it was still unknown whether the country received any actual looted gold. He also recounts that after the war, the U.S. held that nations only had to return looted gold if they had purchased it directly from the Reichsbank, allowing the U.S. to accept such material as collateral for private loans to Spain.[9]

The present whereabouts of the Nazi gold that disappeared into European banking institutions in 1945 has been the subject of several books, conspiracy theories, and a civil lawsuit brought in January 2000 in California against the Vatican Bank, the Franciscan Order and other defendants.[10] The suit against the Vatican Bank did not claim that the gold was then in its possession and has since been dismissed.[11][12]

On October 21, 1946, the U.S. State Department received a top-secret report from U.S. Treasury Agent Emerson Bigelow.[13][14] The report established that Bigelow received reliable information on the matter from the American Office of Strategic Services or U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Command intelligence officials of the U.S. Army.[15] The document, referred to as the "Bigelow Report" (oftentimes as the Bigelow dispatch, or Bigelow memo) was declassified on December 31, 1996, and released in 1997.[16]

The report asserted that in 1945, the Vatican had confiscated 350 million Swiss francs ($1.5b 2020) in Nazi gold for "safekeeping," of which 150 million Swiss francs had been impounded by British authorities at the Austro-Swiss border. The report also stated that the balance of the gold was held in one of the Vatican's numbered Swiss bank accounts. Intelligence reports, which corroborated the Bigelow Report, also suggested that more than 200 million Swiss francs, a sum largely in gold coins, were eventually transferred to Vatican City or to the Vatican Bank, with the assistance of Roman Catholic clergy and the Franciscan Order.[18][19]

Such claims, however, are denied by the Vatican Bank. Vatican spokesman Joaquin Navarro-Valls stated that "There is no basis in reality to the [Bigelow] report".[20]

During the war, Portugal, with neutral status, was one of the centres of tungsten production and sold to both Allied and Axis powers. Tungsten is a critical metal for armaments, especially for armour-piercing bullets and shells. The German armaments industry was nearly entirely dependent on the supplies from Portugal.[21]

During the war, Portugal was the second largest recipient of Nazi gold, after Switzerland. Initially the Nazi trade with Portugal was in hard currency, but in 1941 the Central Bank of Portugal established that much of this was counterfeit and Portuguese leader António de Oliveira Salazar demanded all further payments in gold.[22]

In 2000, Jonathan Diaz, a French bus driver, found documents at the Canfranc International railway station that revealed 78 tonnes (86 short tons) of 'Nazi Gold' had passed through the station.[23][24]

It is estimated that nearly 91 tonnes (100 short tons) of Nazi gold were laundered through Swiss banks, with only 3.6 tonnes (4 short tons) being returned at the end of the war.[25]

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 47 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

|

|

|

جواب |

رسائل 48 من 48 في الفقرة |

|

William Tell and The Templar Nation

The history of Switzerland is, at best, elusive. It is that way seemingly on purpose, with its origins murky. Its…

You must be logged in to view this content.

|

|

|

أول أول

سابق

34 a 48 de 48

لاحق سابق

34 a 48 de 48

لاحق

آخر

آخر

|

|

| |

|

|

©2024 - Gabitos - كل الحقوق محفوظة | |

|

|