They’re shrouded in mystery and conspiracy theories. A history scholar unpacks their real story.

Just mention the Knights Templar and the conspiracy theories start flying. But just who were the medieval Knights of the Temple? What was their job and what happened to them? Why do they still capture our imaginations? The Knights of the Temple—the Templars, for short—were established in the early 1100s under a Rule written by Bernard of Clairvaux,a famous Cistercian abbot. He modified existing Rules for religious monastic communities to fill the need for an armed order in light of the Crusades. This Rule and the Templars’ lifestyle became the model for about a dozen other religious military orders in the Middle Ages.

There are versions of these orders today, some of which can trace their lineage directly back to medieval ancestors. Others have chosen to emulate the original orders but adapt them to our times. These contemporary communities, now often composed of men and women, have turned to massive charitable and philanthropic projects and to protecting endangered Christians. One example of an adapted version of the medieval Templars is the Sovereign Military Order of the Temple of Jerusalem. Other modern expressions of medieval orders are the Knights of Columbus, the Knights and Dames of Malta (who trace their lineage back to the Hospitallers of St. John), and the Knights of the Holy Sepulchre.

Let’s take a look at the history behind the legend of these highly influential knights. It is a tale of medieval palace intrigue worthy of a Hollywood movie, which doesn’t have to make things up to be true.

Monk-Warriors

The story starts at the time of the Crusades. In 1095, Pope Urban II called for European Christian knights to stop fighting each other and to retake the Holy Land from the Muslims. The pope’s speech sent thousands of knights, infantrymen, and a large supporting workforce streaming across Europe, resulting in the taking of Jerusalem in 1099. But these were not unified armies under a tight leadership team. Many knights behaved shamefully and certainly did not live up to the standards of chivalry and charity—even toward fellow Christians. Clearly there was a need for order, control, and standards.

The Templars had their origins at just this point in time. At first, there were about 10 French knights with their retinues escorting pilgrims from the Mediterranean coast to the holy city of Jerusalem and other sites in the area, such as Bethlehem, Bethany, Nazareth, and the Jordan River. The Muslims quickly regrouped, however, and began to take land back in this same period. Their victories led to the Second Crusade (1147‚ 1149), which was promoted by that same Bernard of Clairvaux.

By this time, it was clear that in order for the European Christians to maintain their hold on Jerusalem and keep the passages to Jerusalem safe, a more organized and permanent military presence needed to be set up. Most of the knights from the First Crusade simply left Jerusalem after taking the city in 1099. That group of French escorting knights, then, became the seed for the Templars.

In his Rule for the order, In Praise of the New Knighthood, written in 1128, Bernard of Clairvaux called these fighting men “knights of Christ.” He envisioned them as monk-warriors. The Templars and other orders at first saw their task as fighting to protect pilgrims in the Holy Land, even if that meant taking up arms while still holding to the three traditional monastic vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. Later, it meant protecting the faith from internal threats caused by heretics, once again by violence, if necessary.

Bernard captured the paradox when he said that the knights must be “gentler than lambs, yet fiercer than lions. I do not know if it would be more appropriate to refer to them as monks or as soldiers, unless perhaps it would be better to recognize them as being both.” He described the model Templar as “truly a fearless knight and secure on every side, for his soul is protected by the armor of faith just as his body is protected by armor of steel.”

Bernard also drew on the just-war tradition to say that, in certain circumstances, Templar violence was permitted and not sinful. “If he fights for a good reason, ” Bernard wrote, “the issue of his fight can never be evil.” Elsewhere in his Rule for the Templars, Bernard stated, “To inflict death or to die for Christ is no sin, but rather, an abundant claim to glory.” So for the Templars, fighting the infidel (literally, “the unfaithful ones”) meant the Muslims in the Holy Land.

The World of the Templars

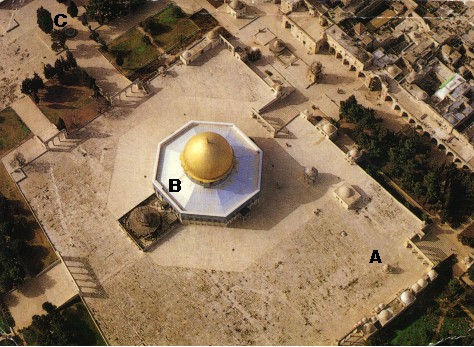

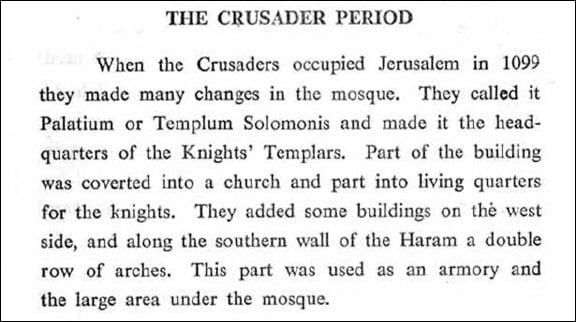

The Templars took their name from their headquarters, situated on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem. This is where Solomon’s Temple had stood from about 970 BC until it was destroyed in 587 BC by King Nebuchadnezzar, who took the Israelites back to Babylon and left Jerusalem a backwater. Centuries later, about 20 BC, the client-king of the Romans, Herod, began to rebuild the Temple, which has come to be known as Herod’s Temple, Jesus’ Temple, or the Second Temple. It was barely completed before it was destroyed by Roman imperial forces in AD 70. Over a thousand years later, the elite knights envisioned by Bernard established their command center in what some still called Solomon’s Temple or Palace.

At its height during the crusading centuries, the Knights of the Temple included about 300 knights who had taken the three standard vows. Many of these vowed knights were in their 20s when they joined. They were supposed to be unmarried, free of debt, and of legitimate birth. They wore a distinctive tunic and wielded shields painted white with a prominent red cross.

The knights were joined by as many as 900 soldiers who were not noble and fought on foot—an infantry to complement the knights’ cavalry.

There would have been hundreds of others, which we would call support staff, employed by the order: blacksmiths, squires, women to cook and take care of clothing, and armorers. Some of the men among this support staff were like lay brothers in other religious orders, such as the Benedictines or Cistercians.

The Templars, like medieval monasteries and convents, were run very collaboratively. They held property and goods in common, making decisions about them and all other matters by vote. They were led by a grand master chosen by the vowed knights in an election.

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

A detail is shown on a replica in which Pope Clement V absolved the Knights Templar of heresy. (CNS photo/Alessandro Bianchi, Reuters)

At the same time, however, elements of Templar life drew attention and led to rumors about them. They reported directly to the pope. They were also exempt from paying taxes, which increasingly became a big deal as they amassed huge areas of land. The Templars also attracted patrons quickly and in large numbers across western Europe.

They eventually enjoyed a network of nearly 2,000 castles, houses, and estates. (A modern-day analogy might be America’s super-wealthy robber baron families who built huge mansions they called cottages in the days before income tax.) We can see the mysteries that persist today started early.

Behind Closed Doors

Above all, the Templars held all of their deliberations and votes in secrecy. When they were fighting the infidel and protecting pilgrims, this was not an issue. But when the Crusades ran their course and Muslims systematically took back Holy Land territory and negotiated treaties for safe passage for Christian pilgrims, the Templars began to lose their reason for being there. When Muslims took Acre in 1291, Holy Land crusading effectively ended—leading to the next and final chapter for the Templars.

With no need to fight in the Holy Land, the Templars largely turned from military affairs to the worlds of finance, estate management, trade, banking, and overseeing investments along their network of tax-exemptproperties in Europe. They were likely the richest operation in the Middle Ages, essentially making them Europe’s ATM.

They were not without enemies, and their worst one was Philip IV, king of France. He is also known to history as Philip the Fair (le Bel), who reigned from 1285 to 1314. He had been trying to control the papacy and Church in France for some time by taxing the clergy without papal permission.

Effectively, he was trying to separate Catholic France from papal authority (later known as Gallicanism). Philiphad particularly tangled with a stubborn pope named Boniface VIII (1294‚ 1303). The king had even sent armed men to intimidate Boniface because the pope planned to excommunicate him. Boniface died shortly after this verbal assault and physical threat, perhaps as a result of the shock of the ugly episode.

Philip continued to pressure the papacy, this time in the person of the weak Pope Clement V (1305–1314), the first of the line of 14th-century popes who resided in Avignon and not Rome. This royalty-versus-papacy fightimp acted the Templars because Philip was in a towering pile of debt to the military order. Trying to get out of repaying, the French king accused the Templars of losing the Holy Land and not living up to their own high standards. Now he had the pope as a powerful tool to attack the Templars.

To take them down, Philip exploited the mystery behind the Templar practice of secrecy. He accused them of black magic, sodomy, and desecration of the cross and Eucharist. The French king engineered an overnight mass arrest of Templars in October 1307. Over the next four years, nearly all Templars were exonerated at trials held across Europe with the notable exception of France. There, after being tortured, some Templars confessed to doing things like spitting on the cross or denying Jesus during secret initiation rites. Many later took those confessions back, saying they had admitted such things only under pain and fear of death.

The End of an Era

The final act took place at the general Church council held at Vienne from 1311 to 1312. Philip was in charge and made sure only bishops supporting him and not Pope Clement were present, to the point of knocking the names of anti-royal bishops off the list of those invited. Even under pressure from the French king, the bishops still voted in a large majority against abolishing the Templars and said the charges against them were not proven.

Philip played his hand by threatening violence against a pope once again. He pressured Clement to condemn his papal predecessor Boniface as a heretic. What the French king really wanted was to get out of debt to the Templars and seize their assets. Pope Clement allowed the Templars to be railroaded by trading off that threat against Boniface, which would endanger his own position as a papal successor. Clement went against his bishops and suppressed the Knights of the Temple on his own papal authority. Quite simply, the pope had been bullied by the king and he gave in. Clement praised “our dear son in Christ, Philip, the illustrious king of France,” adding remarkably, “He was not moved by greed. He had no intention of claiming or appropriating for himself anything from the Templars’ property.”

But instead of handing their money and property over to Philip, as the king wanted, the pope showed some courage and assigned the Templar assets over to the Knights of the Hospital (the Hospitallers). Philip got his cut, of course, and was out of debt to an order that no longer existed, but he didn’t win entirely. Pope Clement never said whether or not the Templars were guilty of heresy or other crimes.

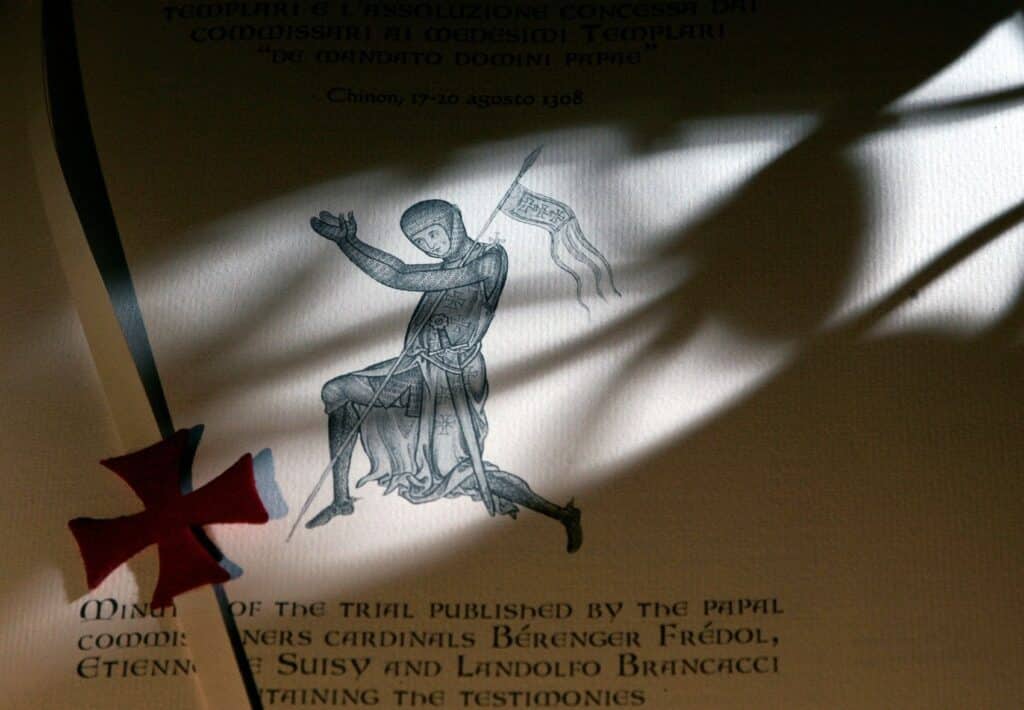

In fact, in 2001, Vatican researcher Barbara Frale discovered in the archives there a misfiled document that has come to be called the Chinon Parchment. This collection details trial and investigation records in Latin from 1307 to 1312. A measure of the continuing interest in the Templars may be found in the fact that a limited reproduction edition of the Chinon Parchment was produced in 2007. Titled Processus Contra Templarios (“Trial against the Templars”), each of the 799 copies cost over $8,000. The 800th copy was given for free to Pope Benedict XVI.

The Chinon Parchment proves that Pope Clement definitely believed in 1308 that the charge of heresy against the Templars was not true, although they were guilty of other, smaller crimes. But Clement just wasn’t strong enough to protect the Templars from annihilation. Finally, in 1314, the Templar Grand Master Jacques de Molay was burned at the stake as a lapsed heretic after he retracted his tortured confession and asserted his innocence. The history of the Templars had come to an end, but its reputation for secrecy and all of this palace intrigue seemed destined to make the myths about them continue to live on.

Sidebar: Conspiracies and the Templars

Because of their secrecy and power, the Templars have refused to die—in myth if not in fact. In part because people want to believe nearly anything about the Church (witness the legend of Pope Joan), the Templars are ripe for exploitation. Spend 10 minutes searching the Internet with the words Templars and conspiracy.

The Templars show up as mysterious and shadowy figures in Hollywood movies like The Da Vinci Code, where they are linked with the Priory of Sion as guardians of Jesus’ alleged descendants with Mary Magdalene. Take nearly any mysterious group or object and the Templars are linked by innuendo and rumor: the Temple Mount, the Ark of the Covenant, the Holy Grail, the True Cross, the Shroud of Turin, and the Freemasons. One legend says they magically appeared to turn the tide of a battle in Scotland. Another claims they crossed the Atlantic Ocean before Columbus. Some of the wilder stories tie the Templars to President John F. Kennedy’s assassination in 1963 and even Pope Benedict XVI’s resignation in 2013—and that’s before we get to the video games and The Templar Code for Dummies.

Perhaps all of this spookiness can be brought back to their end. It happened that the Templars were rounded up on Friday the 13th of October, 1307, which some people claim is the root of that feared calendar date. Moreover, as he went to his death at the stake, Grand Master Jacques de Molay supposedly issued a curse that he would meet PopeClement and King Philip with God within a year—and indeed both pope and king died shortly after.

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/NYOFE4SO2JCGHF6IIT6EMBXGXI.jpg)

Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes.

Según “La Leyenda dorada”, escrita en 1276, por el dominico italiano, Jacques de la Vorágine, María Magdalena era hija de Siro y Eucaria, una familia que descendía de reyes.