El 29 de junio de 1987 un grupo de desconocidos profanó la tumba de Juan Domingo Perón en el Cementerio de la Chacarita y seccionó seccionado y robó las manos del cadáver (Télam)

Para mediados de 1987, la joven democracia recuperada de la Argentina navegaba por aguas turbulentas. El gobierno de Raúl Alfonsín venía de superar, con una salida negociada, el primer levantamiento de los oficiales carapintadas que se oponían a los juicios por los crímenes de lesa humanidad cometidos durante la dictadura, enfrentaba una situación económica difícil con un Plan Austral que empezaba a hacer agua y el tránsito hacia las elecciones legislativas y de gobernadores avanzaba en medio de un clima enrarecido.

En ese contexto, el 1° de julio –justo para el aniversario número 13 de la muerte de Juan Domingo Perón–, una noticia explotó en los medios y sumó un ingrediente tan insólito como inesperado a la situación: un grupo de desconocidos había profanado la tumba del expresidente en el Cementerio de la Chacarita y había seccionado y robado las manos del cadáver.

La conmoción que provocó el robo se amplificó rápidamente en medio de un rompecabezas de versiones que iban desde las motivaciones políticas del caso hasta hipótesis extorsivas, económicas, revanchistas y esotéricas.

Casi 33 años después, el enigma del robo de las manos de Perón no sólo sigue envuelto en el misterio sino que fue potenciado por una serie de extrañas muertes, todas de personas que, de una u otra manera, podían aportar indicios para resolverlo.

El robo

El 29 de junio de 1987, un sobrino político de Perón, Roberto García –casado con Delia Perón, sobrina del expresidente– denunció que la tumba había sido violada. En su declaración dijo que cuando la visitó con su esposa, como lo hacían habitualmente, descubrieron que faltaban la gorra, el sable y la bandera argentina que la cubría, que la claraboya estaba rota y que encontraron fragmentos de vidrio en el piso y alrededor del féretro. Dijo también que habían visto un boquete en el vidrio blindado -de 9 centímetros de espesor y 170 kilos de peso, para cuya apertura eran necesarias 12 llaves- engarzado en un marco de acero que protegía el cadáver embalsamado.

La investigación quedó en manos del juez Jaime Far Suau, que convocó a un equipo policial comandado por el comisario Carlos Zunino e integrado por especialistas de rastros de la Policía Federal y peritos forenses. Ya en la bóveda, ubicada en el subsuelo, los peritos utilizaron las 12 llaves y retiraron el vidrio. Al levantar la tapa del féretro descubrieron que al cadáver le faltaban las manos, cortadas posiblemente con una sierra quirúrgica.

Con el féretro abierto se supo que además de las manos faltaba un objeto que pronto adquiriría singular importancia: un poema escrito por la viuda de Perón, María Estela Martínez, que había sido enmarcado y depositado junto al cadáver.

En su informe, los peritos forenses señalaron que las manos habían sido seccionadas con cortes precisos, pero de diferente manera. La mano derecha había sido cortada a la altura de la muñeca, mientras que el corte de la izquierda había sido practicado en la parte más blanda del hueso, por encina de la muñeca. Precisaron también -a partir del análisis del aserrín cadavérico- que los cortes databan de pocos días.

Dentro del ataúd había también un objeto extraño: el dedo de un guante de goma, posiblemente utilizado por los profanadores durante la operación de seccionar las manos.

“Hermes IAI y los 13”

Casi al mismo tiempo que fue descubierta la profanación, dos importantes figuras del Justicialismo recibieron el primer y único mensaje de los profanadores. El presidente del PJ, Vicente Leónidas Saadi, y el secretario general de la CGT, Saúl Ubaldini, recibieron una carta similar en la que se les pedía el pago de 8 millones de dólares a cambio de la devolución de las manos, la gorra y el sable de Perón.

Como prueba de que realmente tenían en su poder las manos de Perón, los autores de la carta, que se identificaban con el enigmático nombre de “Hermes IAI y los 13”, habían cortado en dos el poema de Isabel Perón. Una de sus partes acompañaba a la carta a Saadi, la restante estaba en el sobre que recibió Ubaldini. Las pericias caligráficas probaron que era auténtica.

"El Brujo" José López Rega

La firma, que evocaba a Hermes Trimegisto (“Hermes, tres veces grande”), el nombre griego que se le daba a un presunto sabio egipcio a quien la tradición

ocultista adjudica la invención de la alquimia, agregó al desconcierto general una pista esotérica que hizo pensar que los autores de la profanación tenían alguna vinculación con el recientemente detenido -luego de años de búsqueda- ex ministro de Bienestar Social de Perón e Isabel, José López Rega, conocido como “El Brujo” por su devoción por las prácticas ocultistas.

Las dos cartas, acompañadas por las dos partes del poema de Isabel, fueron la única señal que dieron los profanadores. Nunca más dieron señales de vida.

La hipótesis esotérica

La hipótesis esotérica conectada con el pedido de rescate fue rápidamente descartada por los investigadores. Al no haber una nueva comunicación de los profanadores, se la tomó como una maniobra con la que se intentó desviar la atención del juez.

Sin embargo, las especulaciones sobre motivaciones esotéricas y económicas de la profanación siguieron por vías separadas.

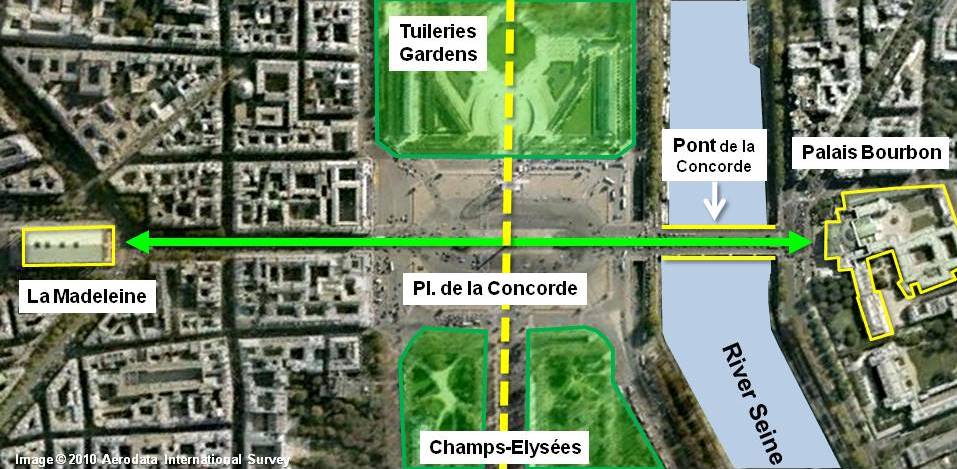

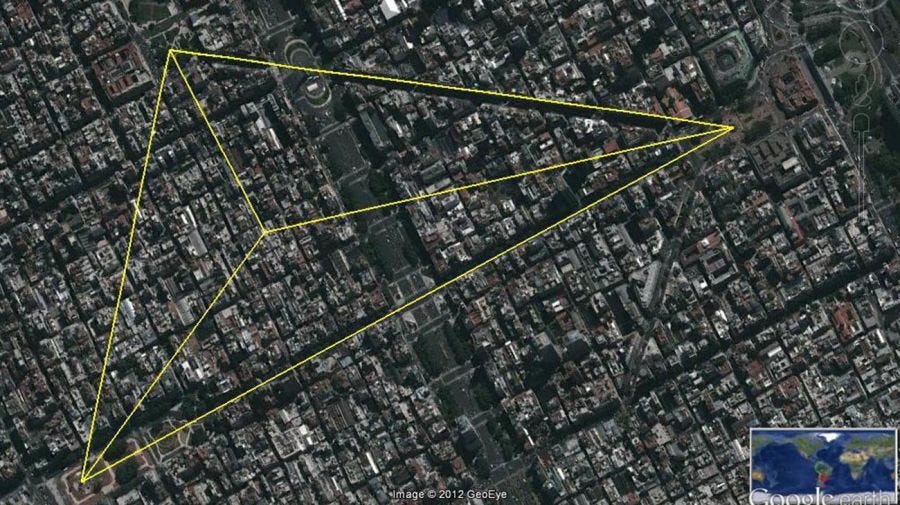

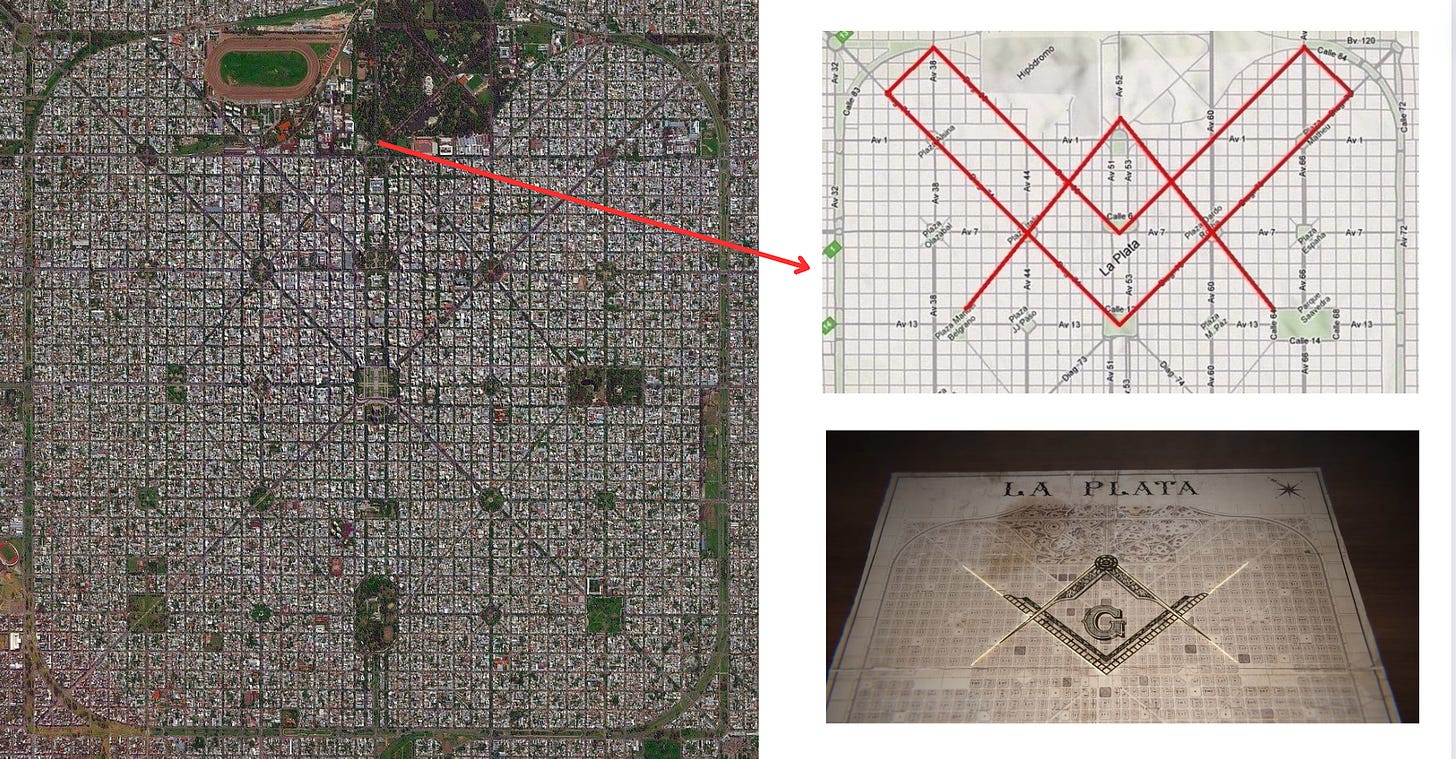

En un primer momento cobró fuerza la posibilidad de que se tratara de una venganza de tipo esotérico debido a las conexiones de Perón con la masonería y la logia italiana Propaganda Due (P2), liderada por Licio Gelli.

María Estela de Martínez señaló cinco posibles responsables: la Logia P2, un grupo integrado por la “mano desocupada” de la dictadura, a un grupo residual de Montoneros, a la masonería inglesa y a los servicios de inteligencia argentinos

Esta posibilidad también fue señalada, junto con otras, por la viuda de Perón. En una primera comunicación telefónica que tuvo con su abogado, Juan Gabriel Labaké, sobre el tema, María Estela de Martínez señaló cinco posibles responsables: la Logia P2, un grupo integrado por la “mano desocupada” de la dictadura, a un grupo residual de Montoneros, a la masonería inglesa y a los servicios de inteligencia argentinos.

Sin embargo, la pista esotérica era la que más peso tenía para ella. “De todas las conversaciones que tuve con ella llegué a la conclusión de que estaba convencida de que la profanación tenía una raíz esotérica”, contaría muchos años después Labaké.

El anillo y el dinero en Suiza

La falta de insistencia en el pedido de rescate por las manos descartó una motivación de índole extorsiva, pero no los móviles económicos de la profanación. Según esta hipótesis, la clave estaba en el anillo que el cadáver de Perón tenía en una de sus manos, o en las manos mismas.

Según la primera de estas versiones, el anillo de Perón guardaba una clave oculta con la cual era posible acceder a la cuenta de un banco suizo donde el general habría guardado una fortuna. Los pedidos de informes judiciales, a través de la embajada argentina de Ginebra, obtuvieron como respuesta que no había ninguna cuenta en los bancos del país relacionada con el expresidente argentino.

La segunda posibilidad era mucho más truculenta: que los ladrones necesitaban las manos para abrir una caja fuerte, un tipo especial de caja fuerte que en lugar de controlarse con una llave o un candado de combinación, funciona con lo que se conoce como un lector de la geometría de las manos. Este tipo de caja fuerte emite un destello de luz incandescente que mide la forma de toda mano que intente abrirla. Las cajas están programadas para abrir sólo bajo las manos de sus dueños.

Desestabilización política

En medio de esa madeja de versiones incomprobables hubo una que fue ganando peso con el correr de los días: el robo de las manos de Perón era parte de una operación política. La pregunta era de quiénes y para qué.

En su momento se esbozaron dos posibles respuestas.

Una de ellas ubicaba al robo como un golpe de fuerte impacto mediático dentro de una operación más amplia que apuntaba a desestabilizar al gobierno de Raúl Alfonsín, poco después del levantamiento carapintada y en medio de un año electoral. En ese caso, los responsables había que buscarlos en los sectores militares carapintadas y en la mano de obra desocupada de la última dictadura, interesados en limar al gobierno para frenar los juicios por los crímenes de lesa humanidad.

Una de las versiones aseguró que el robo fue cometido para desestabilizar al gobierno de Raúl Alfonsín y “crear un estado de confusión y conmoción social con el fin de perjudicar a las instituciones democráticas” (Télam)

En su declaración judicial, el primer jefe de la SIDE del gobierno de Alfonsín, señaló que por orden del presidente había colaborado con la investigación de la Policía Federal y que había llegado a la conclusión de que el robo fue cometido para “crear un estado de confusión y conmoción social con el fin de perjudicar a las instituciones democráticas”.

La otra versión señalaba a la profanación como una operación del propio gobierno con la intención de mostrarla como un hecho brutal de la ríspida interna del Justicialismo. En ese caso, los responsables debían buscarse dentro de la propia SIDE.

En aquel momento, ninguna de las dos hipótesis pudo ser comprobada, pero ocho años después del robo, en 1995, el hallazgo en el sótano de la Comisaría 29 de la Policía Federal de duplicados de las llaves volvió a poner en la mira la posible participación de servicios de inteligencia o de fuerzas de seguridad en la operación.

En todo ese tiempo el proceso de investigación no había avanzado, pero sí sumado una serie de muertes misteriosas.

Los muertos de las manos de Perón

El primer juez de la causa, Jaime Far Suau, murió en noviembre de 1989 junto a su mujer en un supuesto accidente automovilístico en la Ruta 3, cerca de Coronel Dorrego. Su auto volcó en un tramo recto, sin que se encontrara ningún elemento que justificara el accidente. Inexplicablemente, la investigación del caso no ordenó que se le hiciera una autopsia.

Poco después de su muerte, desapareció de la sede del juzgado una carpeta negra donde el magistrado guardaba la transcripción de su charla con Isabel Perón e importante documentación relacionada con el caso.

Meses antes, en febrero, el jefe de la Policía Federal, Juan Ángel Pirker -una de las personas que más sabía sobre el caso-, había muerto en su despacho, presuntamente de un ataque de asma.

La cadena de muertes relacionadas con el caso incluye también a dos testigos.

La foto del cuerpo del general Perón

Uno de ellos, Paulino Lavagna, cuidador del Cementerio de La Chacarita, había denunciado varias veces que lo querían matar. Murió pocos meses después de la profanación, en el predio del cementerio, mientras estaba trabajando. El certificado de defunción, que señalaba que había muerto por “un paro cardiorrespiratorio no traumático” no convenció al juez Far Suau, que ordenó que se le hiciera una autopsia. La pericia determinó que lo habían matado a golpes.

También fue muerta a golpes María del Carmen Melo, una mujer que llevaba continuamente flores a la tumba de Perón. Poco antes de que la asesinaran se había puesto en contacto con el juzgado diciendo que podía dar la descripción de un sospechoso de había rondado la bóveda en los días previos al robo de las manos.

Ninguna de esas dos muertes fue esclarecida.

Mejor suerte tuvo el jefe policial de la investigación, el comisario Carlos Zunino. Sobrevivió luego de que le dispararan en la cabeza en un atentado cuyos responsables no fueron encontrados nunca.

El misterio continúa

Luego de la muerte del juez Far Suau la investigación quedó paralizada. Ninguno de los jueces que lo subrogaron avanzó en la causa, que terminó archivada.

Recién en septiembre del 1994, el juez de Instrucción Alberto Baños la reabrió y se centró en la hipótesis que señalaba al robo de las manos de Perón como parte de una maniobra de desestabilización política, reforzada por el hallazgo de los duplicados de las llaves en la Comisaría 29.

Con ese nuevo dato se especuló que los autores de la profanación habían abierto con ellas el féretro para cortar las manos del expresidente y que el boquete en el vidrio blindado y otras pistas que dejaron en la bóveda habían sido, en realidad, maniobras para desviar la investigación.

Casi 33 años después sigue sin saberse la verdad.

SEGUÍ LEYENDO:

El 29 de junio de 1987 un grupo de desconocidos profanó la tumba de Juan Domingo Perón en el Cementerio de la Chacarita y seccionó seccionado y robó las manos del cadáver (Télam)

El 29 de junio de 1987 un grupo de desconocidos profanó la tumba de Juan Domingo Perón en el Cementerio de la Chacarita y seccionó seccionado y robó las manos del cadáver (Télam)

"El Brujo" José López Rega

"El Brujo" José López Rega María Estela de Martínez señaló cinco posibles responsables: la Logia P2, un grupo integrado por la “mano desocupada” de la dictadura, a un grupo residual de Montoneros, a la masonería inglesa y a los servicios de inteligencia argentinos

María Estela de Martínez señaló cinco posibles responsables: la Logia P2, un grupo integrado por la “mano desocupada” de la dictadura, a un grupo residual de Montoneros, a la masonería inglesa y a los servicios de inteligencia argentinos Una de las versiones aseguró que el robo fue cometido para desestabilizar al gobierno de Raúl Alfonsín y “crear un estado de confusión y conmoción social con el fin de perjudicar a las instituciones democráticas” (Télam)

Una de las versiones aseguró que el robo fue cometido para desestabilizar al gobierno de Raúl Alfonsín y “crear un estado de confusión y conmoción social con el fin de perjudicar a las instituciones democráticas” (Télam) La foto del cuerpo del general Perón

La foto del cuerpo del general Perón