|

|

General: TEMPLE MADELEINE CHURCH GENEVA SWITZERLAND CERN INTERNET TIME TRAVEL TIME MACHIN

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

Temple de la Madeleine Church - Geneva, Switzerland

Temple de la Madeleine Church - Geneva, Switzerland

Madeleine Church, Geneva, Switzerland. The Temple de la Madeleine Madeleine Church is located in the foot of the Old Town of Geneva, Switzerland

|

|

|

|

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

|

|

|

|

|

Iglesia de la Magdalena (Venecia)

La iglesia de Santa María Magdalena (en italiano: chiesa di Santa Maria Maddalena, conocida habitualmente como La Maddalena, es una iglesia de Venecia situada en el sestiere de Cannaregio, que constituye uno de los ejemplos más conocidos de la arquitectura neoclásica veneciana.

Detalle de una estatua, fotografía de A. Liuzzi.

Se tienen noticias de un edificio religioso construido en el mismo lugar en 1222, propiedad de la familia patricia Baffo (o Balbo). Tras la firma en 1356 de la paz entre Génova y Venecia, el día de Santa Magdalena se convirtió en festivo por decisión del Senado veneciano y la iglesia fue ampliada, incluida también una torre de guardia dedicada a campanario.

A partir de 1763 la iglesia fue reconstruida completamente con una planta circular, según el diseño de Tommaso Temanza, que trasladó su orientación hacia el campo. Las obras terminaron en 1790 bajo la dirección de Giannantonio Selva. En 1810 se revocó su papel de iglesia parroquial y en 1820 fue cerrada, para ser reabierta a continuación como oratorio. En 1888 se demolió el campanario, que estaba en peligro de derrumbe. Actualmente es una iglesia rectorial dependiente de la parroquia de San Marcuola (vicaría de Cannaregio-Estuario, patriarcado de Venecia).

Vista frontal.

La iglesia presenta una planta circular bastante insólita para Venecia (el único otro ejemplo es San Simeon Piccolo), cubierta con una cúpula hemisférica inspirada claramente en la arquitectura de la antigua Roma y en particular en el Panteón, del cual retoma además los escalones en el exterior.1 También se inspiró en edificios venecianos como la Salute y San Simeon Piccolo, obra esta última de Giovanni Antonio Scalfarotto, maestro y tío de Tommaso Temanza. Las cenizas de Temanza reposan en esta iglesia, apenas pasada la entrada lateral.2

De gran valor arquitectónico es el portal, que es en realidad un pronaos acortado, precedido por una breve escalinata y formado por un alto tímpano triangular sostenido por dos parejas de semicolumnas con capitel y entablamento jónicos. Sobre la puerta de entrada hay una luneta con un ojo de la providencia representado dentro de un triángulo entrelazado con un círculo en bajorrelieve, considerado a menudo un símbolo masónico (parece que la familia Baffo pertenecía al orden templario).2 En el exterior del ábside se encuentra, en el paramento de mármol, un bajorrelieve que data del siglo xv y representa una Virgen con el Niño y santos.

En el interior, la planta circular se transforma en hexagonal con cuatro capillas laterales (los otros dos lados están formados por la capilla mayor y por la entrada principal), enmarcadas por arcos de medio punto. El presbiterio cuadrado se desarrolla en anchura con dos exedras laterales, recordando una tradición véneta iniciada por la iglesia del Redentor.1 El entablamento de la gran cúpula hemisférica con linterna está sostenido por doce columnas jónicas geminadas, entre las cuales se abren pequeñas hornacinas semicirculares a dos niveles: las superiores están ocupadas por estatuas que representan a las santas Magdalena e Inés y los profetas Isaías y David. El interior fue concebido por Temanza como un gran espacio blanco, terminado en marmorino.

La Última cena de Giandomenico Tiepolo.

La iglesia conserva importantes cuadros del siglo xviii, entre ellos la Última cena de Giandomenico Tiepolo y la Aparición de la Virgen a san Simón Stock de Giuseppe Angeli, además de lienzos del siglo xviii realizados por la escuela de Giovanni Battista Piazzetta.

En 2005, en el curso de restauraciones consistentes en la retirada del enyesado aplicado en el siglo xix para sacar a la luz el originario marmorino del siglo xviii, se descubrió, en la luneta que hay sobre el altar, un fresco alegórico monocromo de Giandomenico Tiepolo que representa la Fe y que originalmente estaba sobre el cuadro de la Última Cena.3

|

|

|

|

|

3 opiniones sobre Campo della Maddalena

Un rincón mágico en el corazón de Veneci

El Campo della Maddalena, situado en el barrio de Cannaregio, es una preciosa plaza situada cerca de una de las principales calles de esta zona de la ciudad, Rio Terà della Maddalena.

Allí se encuentra uno de los principales ejemplos de la arquitectura neoclásica veneciana, la iglesia de Santa María Maddalena, más conocida como La Maddalena. Se trata de una de las iglesias más amadas por los venecianos, pues el día de Santa Maddalena se conmemora la firma de la paz entre las Repúblicas de Génova y Venecia en 1356.

Otro edificio singular que se encuentra en esta plaza es el palacio

En el que el poeta Innocente Giuseppe Lanza (1893-1963) fundó la Societa' Lunatica Benefica.

https://www.minube.com/rincon/campo-della-maddalena-a599521 |

|

|

|

|

La Maddalena and Masonic Symbolism

La Maddalena and Masonic Symbolism. This small church in Cannaregio, is notable for its unusual round form and masonic symbolism.

Designed by Tommaso Temanza, with a circular plan inspired by the Pantheon in Rome; the current small church of Santa Maria Maddalena, was begun in 1763 and completed in 1780.

It is rarely open for visits, except during occasional exhibitions, including the Venice Biennale. To some, it appears to amplify the mysteries of this church.

It is located in a small campo, that opens out on to the main pedestrian “Strada Nuova” through-route; linking Rialto with the Railway Station.

Location

History

Links to Freemasonry

Brief development of Freemasonry in Venice

Links (internal-external)

Santa Maria Maddalena in the district of Cannaregio, usually referred to simply as “La Maddalena”.

LOCATION

Santa Maria Maddalena in the district of Cannaregio, usually referred to simply as “La Maddalena”. It is located in the small Campo di Maddalena, which opens onto the main “Strada Nuova” through route; linking Rialto with the Railway Station.

This section of the Strada Nuova, is called the “Rio Terra Maddalena” and was originally a filled-up canal (or Rio Terra).

The closest waterbus stop is “San Marcuola” on the Grand Canal, just a few minutes walk to the south-west.

La Maddalena and Masonic Symbolism – History

The first church here was built in 1220, by the patrician Balbo family; probably on the site of a fortified house-castle. There is some evidence of the family’s association with the Knights Templar. Traces of the path left by the Templars’, are still visible today. In fact, they were still in existence in Venice, until the order was disbanded in 1312. Legend has it, that their fabled treasure was hidden for some time, on the Venetian island of St. Giorgio in Alga.

Above: Note the Bell-Tower, that was demolished in 1888, features in an old print.

After the end of the four wars, that led Venice against Genoa and ended in 1356; the Senate decided each year to hold public celebrations, in honour of St Mary Magdalene.

It was decided to enlarge the church, including a watchtower; which was turned into a bell tower. The bell tower was demolished in 1888.

The church was restored in the early 18th century, but by 1780, it was entirely rebuilt in a neoclassical design by Tommaso Temanza, with a circular plan inspired by the Pantheon and Santo Stefano Rotondo, in Rome. Temanza, was better known as a theorist and historian and this is one of his few completed buildings.

This makes it the last religious building undertaken, under an independent Venetian Republic. The only other round churches in Venice are La Salute and San Simeon Piccolo.

During French rule, the church lost its status in 1810 as a parish church, in 1820 it was closed; to again serve as an oratory. The bell tower was demolished in 1888. Today, the church belongs to the municipality of San Marcuola.

The present interior has a compact form that is dodecagonal. with four side chapels and a presbytery. Twelve ionic pillars that symbolise the apostles, support the dome. Four Ionic half-columns support the tympanum and attic.

In the lunette of the portal, is an allegorical representation of the Solomon Islands and divine wisdom. Right next to the entrance in the interior, is a painting by Giandomenico Tiepolo, of “The Last Supper”.

Outside the apse, is a 15th-century bas relief of the Madonna with Child.

La Maddalena and Masonic Symbolism – Links to Freemasonry

The most notable feature is the flat portal, with probable masonic symbolism of “the eye within the triangle” over the doorway.

Obviously round churches have existed since antiquity and the “eye within the triangle”, has long been a Christian symbol. However, there is further strong associations with Freemasonry here.

Thomas Temanza, frequented the circle of Andrea Memmo, a procurator of San Marco, who, together with his brothers Bernardo and Lorenzo; were amongst the first most well-known Freemasons in Venice. They were initiated by non-other than Casanova!

Also, on the pediment is the inscription “Sapienta aedificavit sibi domun”, which might be translated to read ”Wisdom built this House Herself” – a motto that appears to deny the role of God.

Further evidence of Freemasonry can be seen inside.

Temanza’s church originally, had only a single altar, “for a single Supreme Being”; as the Masonic creed urged. Contrary to custom in other Venetian churches, there were no altars to the Virgin, Mary Magdalene, or any other saint. Two additional altars were later added, to erase this Masonic influence.

Another piece of evidence, is that inside is the tombstone of Tomasso Temanza, bearing the date of his death (1789), a compass, ruler and set-square. Admittedly, the tools of his architectural profession; they are also well-known Masonic symbols.

Brief development of Freemasonry in Venice

It was the “Age of the Enlightenment” and the rationalism associated with the Masons, was in vogue. In the 18th century, Venice had an influential fraternity of freemasons.

In 1746, a lodge was founded in Venice, which became associated with Giacomo Casanova, Carlo Goldoni, and Francesco Griselini. It survived until 1755, when the intervention of the “Inquisition”; led to the arrest of Casanova and the dissolution of the lodge.

Above: The tombstone of Tomasso Temanza, bearing the date of his death (1789), a compass, ruler and set-square.

New lodges were founded in 1772, with warrants from the Premier Grand Lodge of England, in Venice and Verona, on the initiative of the Secretary of the Senate, Peter Gratarol; which remained active until 1777.

The Rite of Strict Observance established a chapter in Padua in 1781, which opened another in Vicenza shortly afterwards.

All Freemasonry was suppressed in 1785.

The start of the unification process in 1859, saw a revival in Freemasonry. Giuseppe Garibaldi, a leader of Italian unification, was an active mason and a keen supporter of the craft. In the 1920’s, Freemasonry was again suppressed under Fascism; but revived again after the fall of Benito Mussolini.

Links (internal–external)

Please see my other related posts, in the category of: History and Architecture

For those interested in the mysterious, mythical or dark side of Venetian history and culture; I have put together a list of links below to those posts that include elements of Christian Symbolism, Sacred Geometry, Kabbalah, Freemasonry and Alchemy, which I hope to expand.

Eye of the Triangle

Sacred Geometry

St Mark’s Basilica

The Lion of St Mark

Santa Maria della Salute

Symbolism of the Venetian Cross

Palazzo Lezze and Alchemic Symbolism

Kabbalah and San Francesco della Vigna

https://imagesofvenice.com/la-maddalena-and-masonic-symbolism/ |

|

|

|

|

|

| Napoleon Bonaparte on horseback. |

|

|

| First |

Name: Napoleon Bonaparte |

| Second |

Position: General, Doge of Genoa, King of Italy |

| Third |

Nationality: Corsican |

|

|

| Fourth |

Allegiance: Genoa |

| Fifth |

Born: 15 August, 1769 |

| Sixth |

Died: 14 June, 1806 (aged 36) |

| | |

Napoleon Bonaparte (Italian: Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 14 June 1806) was a Genoese military and political leader who rose to prominence during the latter stages of the French Revolution and its associated wars in Europe.

Napoleon was born at Ajaccio in Corsica in a family of noble Italian ancestry which had settled Corsica in the 16th century. He trained as an artillery officer in France. He rose to prominence after he allied Genoa with Republican France and led a successful campaign against the Austrians in the Italian peninsula.

Napoleon rose to become Doge of Genoa in 1797 and led a second campaign against the Austrians in 1800. Napoleon was thus able to create a Kingdom of Italy in Northern Italy and become King of Italy. As King, he created the Napoleonic Code, which is still used in Italy.

In 1804, Napoleon faced once again an enemy coalition, this time the Austrians and the Russians. With the help of Bavaria and France, Napoleon managed to crush the coalition's armies and went as far as Poland. He also achieved his greatest victory: Austerlitz.

However, during the battle of Friedland, Napoleon was killed. Napoleon's military campaigns are still studied in military academies all over the world and in Italy he is viewed as a national hero.

https://alternativehistorychristos.fandom.com/wiki/Napoleon_Bonaparte_(Genoa)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Napoleon Bonaparte was Ligurian!

After Christopher Columbus and Pablo Picasso, he is other famous figure with connections to this region. And this is not the last famous character I will write about! Of course, don’t get me wrong! Everything you learned about Napoleon Bonaparte is true! But I’m starting from the beginning:

Sarzana

I have already written about this town (check here) located on the eastern end of Liguria, right on the border with Tuscany. Walking around the historical center, you will come across a tenement house that belonged to the BUONAPARTE family (when Napoleon started his career in France, he changed his surname to Bonaparte). Research on Napoleon’s family tree showed that his father’s family had been living there for centuries. More precisely, from the beginning of the 14th century, and this fact is confirmed by a document from 1322, in which we read that “Giovanni Buonaparte di Sarzana was the owner of 2/3 of the house with a tower and a garden, located near the church of St. Andrew” – where it stands to this day.

Corsica

At the beginning of the 18th century, the Buonaparte family moved to Corsica, which at that time was part of the Republic of Genoa (currently Liguria). However, the rebellious Corsicans constantly initiated levée en masses, which were aimed at becoming independent from the domination of Genoa. They succeeded in 1755. However, the Republic of Genoa didn’t want to let them go and, together with France, tried to recapture the island and reincorporate it into its colonies. Nonetheless, the pact that was signed by both countries put Genoa in tough conditions and it was forced to cede the island to France. Since then Corsica belongs to this country. At the same time, Genoa’s dominance has left its sign to nowadays! To this day, Corsicans, proud of their own language in reality speak in the Ligurian dialect that was imported with the Ligurian conquistadors!

Buonaparte

Let’s go back to Napoleon’s family. His parents were both born in Ajaccio, in Corsica, at a time when it belonged to the Republic of Genoa. They had 13 children, 8 of whom lived to adulthood. At Buonaparte’s house, Italian and Genoese were spoken habitually. The result was that Napoleon Bonaparte spoke and wrote badly French – his misspellings were well known and were very common even in official documents written in French!

The rest of Napoleon’s life you know from lessons at school, but this intriguing detail about this famous French is worth to be highlighted

https://thatsliguria.com/en/napoleon-bonaparte-was-ligurian/

|

|

|

|

|

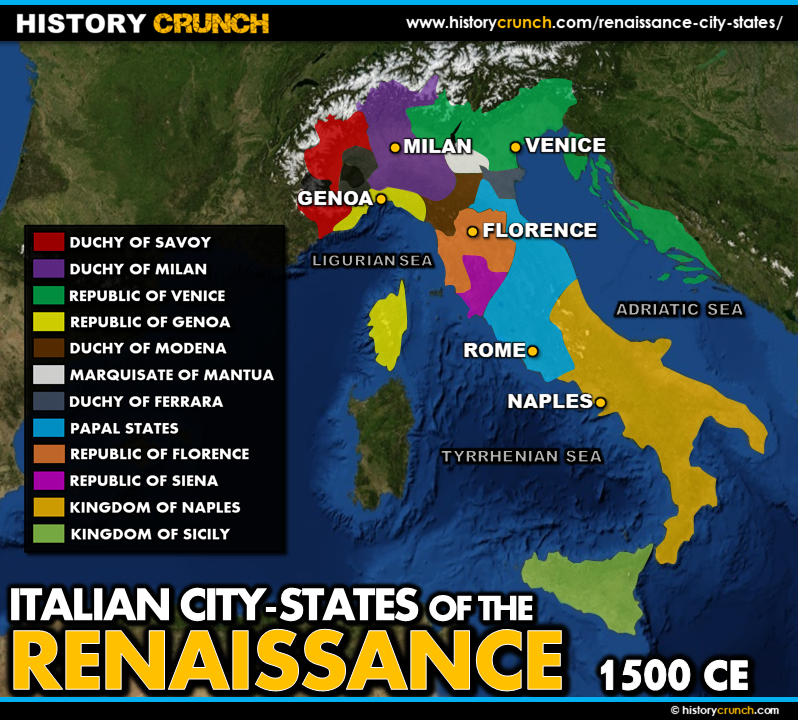

La edad de oro de los banqueros genoveses

[editar]

Durante la década de 1450-1460, la República de Génova se convirtió en un peón en la lucha entre el Reino de Francia y el Reino de Aragón por el poder y la influencia en Italia. Entre 1455 y 1475, perdió además todas sus posesiones en el Mediterráneo oriental (en los mares Egeo, de Mármara, de Azov y Negro). Este cambio impelió a los genoveses a buscar nuevas plazas comerciales, como fueron Plasencia, Besanzón y Amberes.

Génova en la Italia del 1600.

Amenazado por Alfonso V de Aragón, el dogo entregó la República a los franceses en 1458; Génova se convirtió en un ducado sometido a un gobernador real francés, Juan de Anjou. Sin embargo, con el apoyo de Milán, Génova se rebeló y se restauró la república en 1461. No obstante, los milaneses luego cambiaron de bando y conquistaron Génova en 1464, que se mantuvo como feudo de la Corona de Francia. Estuvo ocupada por los franceses o los milaneses durante gran parte del período. De 1499 a 1528, la República llegó a su punto más bajo, estando bajo ocupación francesa casi continua. Los españoles, con sus aliados intramuros y la "nobleza" atrincherada en las fortalezas de las montañas detrás de Génova, capturaron la ciudad el 30 de mayo de 1522, sometiéndola a saqueo. Cuando el almirante Andrea Doria de la poderosa familia Doria se alió con el emperador Carlos V del Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico para expulsar a los franceses y restaurar la independencia de Génova, abrió una perspectiva renovada: 1528 marcó el primer préstamo de los bancos genoveses a Carlos. Doria y el emperador firmaron un acuerdo por el que los genoveses alquilaban sus servicios navales para garantizar las comunicaciones entre los territorios de la Corona española. El pacto garantizaba además la autonomía política de la república; cuando el emperador solicitó la sumisión genovesa a principios de la década siguiente, los genoveses rehusaron tajantemente la petición.

Doria implantó una serie de reformas políticas para reforzar el gobierno de la república. Creó el Gran Consejo, encargado de elegir al dogo y velar por la administración, y el Consejo Menor, ambos compuestos de nobles. El Senado quedó encargado de la administración de justicia. Se limitó además el acceso a los cargos políticos a los miembros de las casas nobles, los alberghi, que se redujeron a tan solo veintiocho cuando a principios de siglo habían sobrepasado el centenar. Con esta medida, los artesanos perdieron todo poder político. Los miembros del Gran Consejo se escogían por sorteo entre los nobles; el consejo elegía luego a dos gobernadores vitalicios, sometidos al dogo, escogido cada dos años, también entre las familias aristocráticas. También en 1528 se ennobleció a las familias más poderosas de los mercaderes y artesanos, sin que por ello desapareciese la rivalidad entre esta nueva nobleza y la antigua, dedicada fundamentalmente a las finanzas. Las tensiones llevaron incluso al estallido de una guerra civil entre las distintas facciones en 1575, tras el fallecimiento de Doria en 1560.

A partir de entonces, Génova sufrió algo así como un renacimiento como asociado menor del Imperio español, con los banqueros genoveses, en particular, financiando muchos de los esfuerzos exteriores de la Corona española desde sus casas de conteo en Sevilla. Fernand Braudel incluso ha llamado al período 1557-1627 la «edad de los genoveses», aunque el visitante moderno que pasa ve brillantes manieristas y palacios con estilo Barroco a lo largo de Génova Strada Nova (actual Via Garibaldi) o via Balbi no puede dejar de notar que no había riqueza conspicua, que en realidad no era genovés, pero concentrada en las manos de un círculo muy estrecho de banquero-financieros, verdaderos «capitalistas de riesgo». El poder comercial de Génova, sin embargo, siguió dependiendo estrechamente en el control de vías marítimas del Mediterráneo y la pérdida de Quíos, arrebatada por el Imperio otomano, en 1566, dio un golpe grave. Para compensar la pérdida de territorio a manos de los otomanos, el imperio español entregó Panamá Viejo en América como concesión comercial a los genoveses.9 Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera quien fue gobernador de Panamá, sabiendo de la participación histórica de los genoveses en las Cruzadas, reclutó a genoveses que se establecieron en Panamá, así como a peruanos y panameños nativos, en una guerra contra los musulmanes de Filipinas, y fundó la ciudad de Zamboanga.10

La población de la ciudad creció entre un treinta y un cuarenta por ciento durante el siglo, y su flota pasó de las dieciocho mil toneladas de 1460 a las treinta y un mil en 1560. A mediados de siglo era la segunda armada del Mediterráneo, tras la veneciana. Hasta finales de siglo, el poderío naval genovés se centró en repeler el avance otomano, que cesó el último cuarto tras la derrota de batalla de Lepanto, salvo por la actividad corsaria. La ciudad mantenía una de las escuadras que defendían el Mediterráneo hispánico, con entre quince y veintitrés galeras, que tenía encomendada el control del golfo de León y Córcega. Además, suministraba naves a las demás flotas mediterráneas: la escuadra de España, con base en Cartagena, contaba con entre quince y treinta y seis galeras; la de Nápoles, con unas veinte; la de Sicilia, con unas doce y la de la orden de Santiago, que constaba de cuatro navíos. Además de los ingresos por los contratos o compra de las galeras, los genoveses obtenían beneficios del comercio con la península ibérica, el transporte de metales preciosos —con su consiguiente contrabando— y los préstamos a la Corona.

A principios de la Edad Moderna, la ciudad estaba dominada por una oligarquía nobiliaria, resultado de la evolución social en la Edad Media. Cuatro familias señoreaban todos los aspectos de la administración de la república: los Fieschi controlaban la Iglesia; los Doria, el mar; los Spínola y Grimaldi basaban su poder en los numerosos feudos que poseían.

La apertura para el consorcio bancario genovés fue la bancarrota del estado de Felipe II en 1557, que arruino a las casas bancarias alemanas y puso fin al reinado de los Fugger como los financieros españoles. Los banqueros genoveses, siempre que el sistema de los Habsburgo era difícil de manejar, obtenían un crédito de fluido y un ingreso confiable regular. A cambio, los envíos menos confiables de la plata de América fueron trasladados rápidamente de Sevilla a Génova, para proveer capital para nuevas empresas. El banquero genovés Ambrosio Spinola, marqués de los Balbases, por ejemplo, él mismo levantó y dirigió un ejército que luchó en las Guerra de los Ochenta Años en los Países Bajos en el siglo xvii. La decadencia de España en el siglo xvii trajo consigo también la renovada caída de Génova, y las quiebras frecuentes de la corona española, en particular, arruinaron muchas de las casas comerciales de Génova. En 1684 la ciudad fue fuertemente bombardeada por una flota francesa como castigo por su alianza con España.

El empobrecimiento de los banqueros y la falta de protección española hicieron que paulatinamente los favorables a la liga con España cediesen terreno a los partidarios de acordar con Francia. Las sucesivas bancarrotas de la Corona acabaron por arruinar a los banqueros genoveses que le habían prestado dinero para financiar la guerra de los Ochenta Años y la de Treinta Años.

|

|

|

|

|

Historia del Dinero

5 marzo, 2021 | Actualizado 6 marzo, 2023

Básico 15 min lectura

https://academy.bit2me.com/historia-del-dinero/ |

|

|

|

|

A principios del siglo XX surgió la necesidad de resolver los problemas económicos, políticos y sociales de la Europa de posguerra; se pretendía negociar una relación entre las economías capitalistas europeas y el nuevo régimen bolchevique de la Rusia soviética; en este contexto, se realizó la conferencia de Génova en 1922 donde se definió la convertibilidad al oro, el establecimiento de bancos centrales independientes, junto con la asistencia financiera a países en situaciones adversas y la colaboración de los bancos centrales en la administración del sistema financiero internacional. |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

42 a 56 de 101

Siguiente Anterior

42 a 56 de 101

Siguiente Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2024 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|