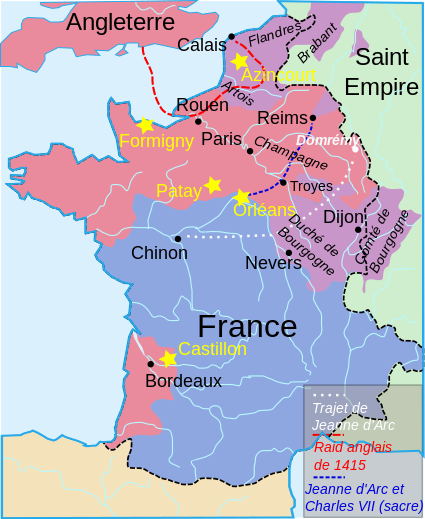

BISMARCK, N.D. (KFYR) - Monday was the 78th anniversary of D-Day, the largest amphibious invasion in history and a turning point in World War II. But the invasion would not have been as successful had it not been for accurate weather forecasts. In fact, the invasion was supposed to happen on June 5 but meteorologists advised the Allies to wait one more day due to poor weather conditions.

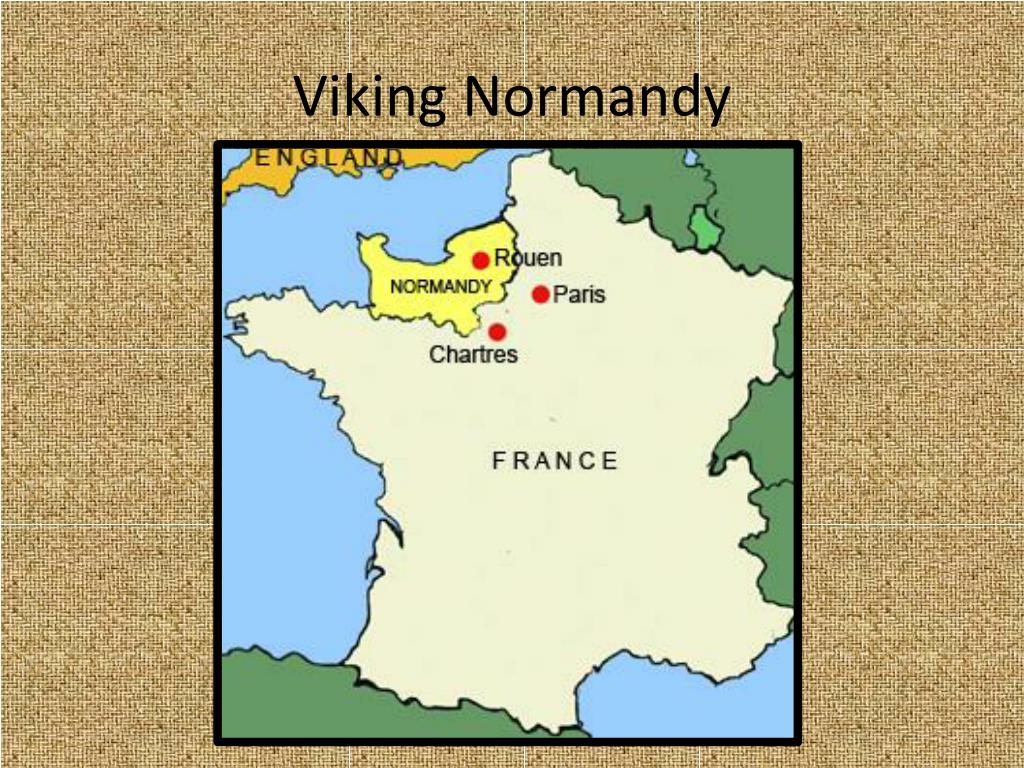

A lot of weather-related variables needed to be taken into consideration when planning a large-scale, complex invasion like the one that was carried out across the English Channel in 1944. For instance, the Navy wanted good visibility and limited waves in the English Channel during the invasion. The Army wanted a firm, dry ground on the beaches. A minimum ceiling, meaning no low clouds, was required for bomber and fighter aircraft. And attacking at a time of low tide was important to expose the underwater German mines. Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower had to take all of these needs into consideration.

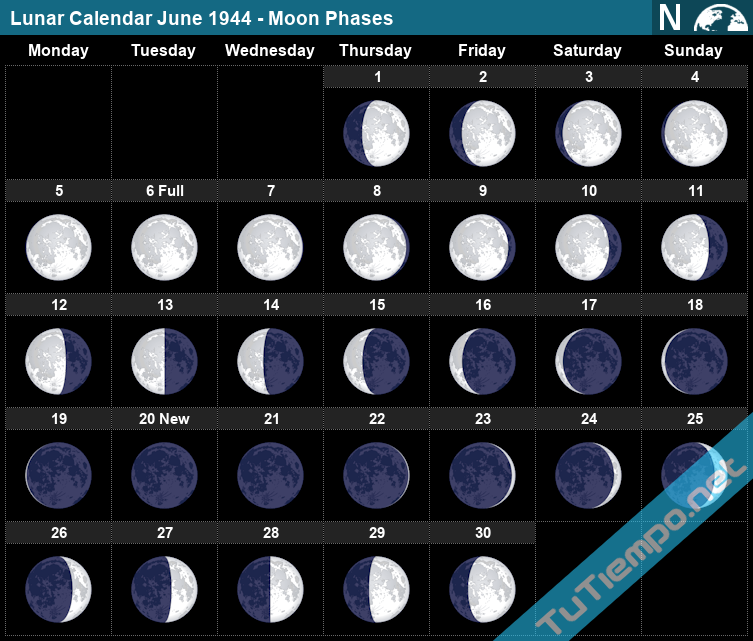

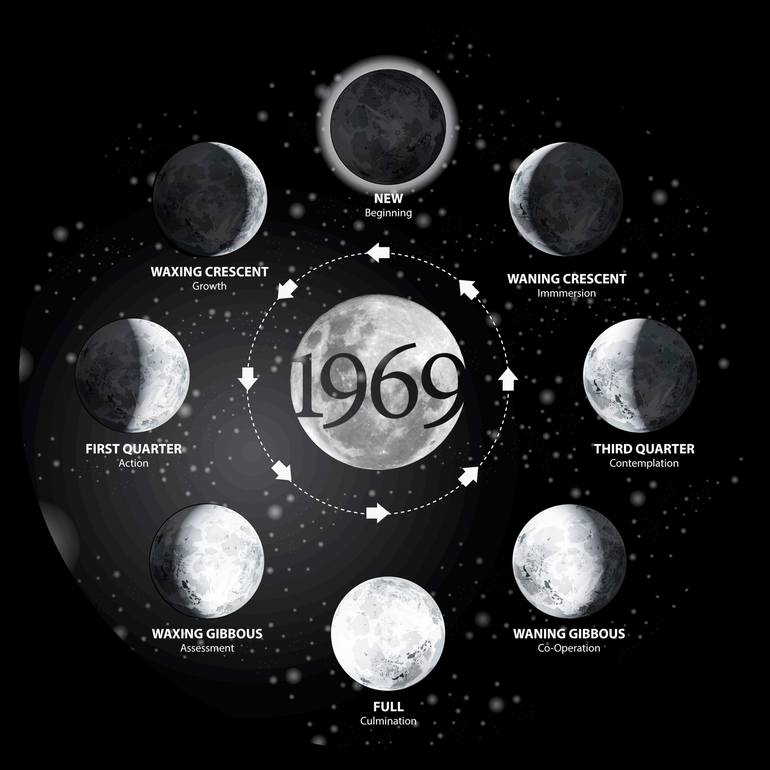

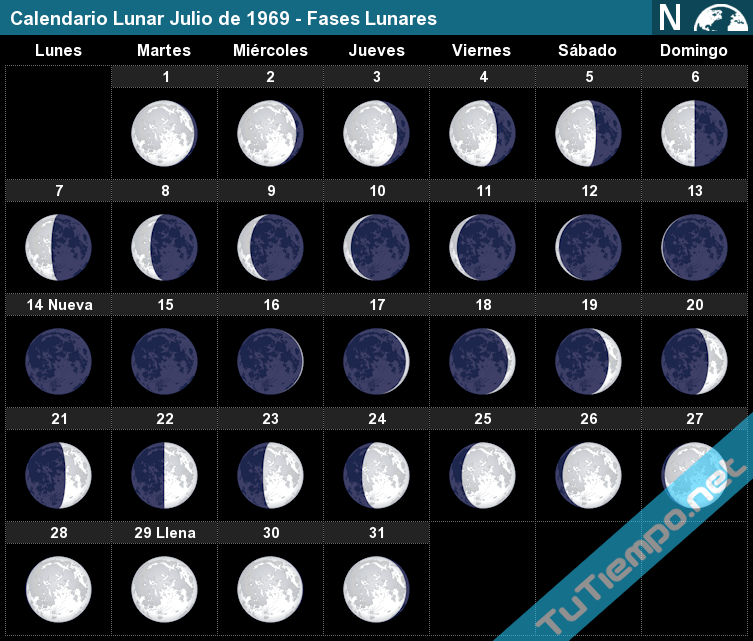

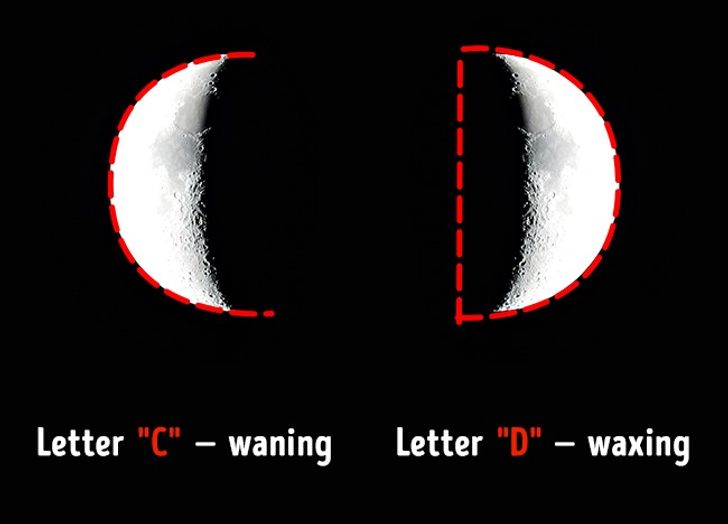

Allied commanders decided on the month of June ahead of time for the start of the Allied invasion to retake Europe. A full moon was to be on June 6, which would have yielded the best illumination for pilots around dawn when the invasion was to begin. Eisenhower chose June 5 for the invasion as long as the weather cooperated.

Three forecast teams, two British and one American, worked independently to assess weather conditions in the region in early June. These teams then reached a consensus with the leadership of Captain James Stagg of the British Royal Air Force and a meteorologist for the Met Office. Stagg then presented these forecasts to Eisenhower.

Keep in mind that this is the 1940s when we didn’t have satellites, weather radar, computer models, and many other technologies that meteorologists rely on nowadays. So a two-day forecast was a huge challenge, especially under these pressures as the weather could determine the success of the invasion.

The Allies relied mainly on surface observations from military and civilian weather observers in the British Isles and in western Europe and a few military observers at sea as a starting point for their forecasts. Since the Allies controlled the Atlantic, having at least a few observations at sea was a bit of an advantage to determine incoming weather patterns since German meteorologists did not have access to as much weather data there.

The overall weather pattern in early June 1944 was rather turbulent over this part of the world. An area of low pressure had set up to the northwest, leading to a parade of storms that barreled across the Atlantic and into the British Isles. Predicting the exact timing, track and strength of these storms put Stagg and his colleagues under almost unimaginable pressure with the fate of the war and perhaps the world hanging in the balance.

The weather map on the morning of June 4 (below) showed an area of low pressure and a cold front approaching the English Channel. At this point, Eisenhower had to make the decision whether to stick with June 5 for the invasion or delay it. Stagg warned him of the incoming storm that would bring another round of rain and wind to the region on June 5, but a short break would likely follow on June 6. On this advice from the meteorologists, Eisenhower delayed the invasion by 24 hours.

This ended up being the right decision as if the invasion had remained on June 5, heavy seas, high winds and thick cloud cover from the potent storm centered north of Scotland would have likely caused the invasion to fail.

While far from perfect, the weather on the morning of June 6 was good enough for the invasion to proceed successfully. The potent storm and area of low pressure had moved far enough to the east to even allow the clouds to break by the afternoon.

In fact, invading on June 6 caught the Germans by surprise as they anticipated the invasion would only happen during a much longer stretch of fair weather. German forecasters predicted that rough seas and gale-force winds were unlikely to weaken until mid-June, so Nazi commanders thought it was impossible that an Allied invasion was imminent.

Weeks later, Stagg sent Eisenhower a memo (below) noting that if the mission had not gone on June 6, the next possible window for an invasion was between June 19-21 and the Allies would have encountered conditions “continuously prohibitive for beach landings” — possibly the worst weather in the English Channel in two decades. Eisenhower wrote back to Stagg at the top of the memo saying: “Thanks to the Gods of War we went when we did.”

Years later, during their ride to the Capitol for his inauguration, President-elect John F. Kennedy asked President Eisenhower why the invasion of Normandy had been so successful.

Eisenhower’s response: “Because we had better meteorologists than the Germans!”