|

|

General: NAPOLEON BONAPARTE S PYRAMID NETHERLANDS AUSTERLITZ

Escolher outro painel de mensagens |

|

|

el 2 de diciembre de 1805, tres grandes ejércitos se encontraron frente a frente cerca de Austerlitz, en la actual República Checa. A un lado estaban las tropas de Napoleón Bonaparte, que ascendían a algo menos de 68.000 hombres; al otro, casi 90.000 soldados rusos y austríacos. La desproporción de fuerzas hacía pensar a los oficiales rusos y austríacos que contaban con una gran ventaja, pero Bonaparte suplió con la estrategia su inferioridad numérica y se alzó con la victoria.

La “batalla de los tres emperadores”, como también se la conoce, es considerada como una de las victorias militares más importantes de Napoleón y una demostración de su genio táctico, además de una de las más brillantes de la historia de la estrategia militar. Gracias a ella logró romper la coalición que se había formado contra él y abrir la puerta a casi una década de hegemonía francesa en Europa.

La batalla de Austerlitz es considerada como una de las victorias militares más importantes de Napoleón y una demostración de su genio táctico

Temerosos del creciente poder militar de Francia bajo el mando de Napoleón, en 1803 una serie de países habían formado una alianza conocida como la Tercera Coalición. Esta incluía al Reino Unido, el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico bajo el liderazgo austríaco, Rusia, Nápoles, Sicilia y Suecia: de entre estos países, Austria y Rusia eran los que más sentían la amenaza francesa y los que podían suponer un problema mayor para Napoleón, por lo que en 1805 el emperador francés desplazó a decenas de miles de soldados hacia el corazón de Europa.

ARTÍCULO RECOMENDADO

La dura vida de los soldados de Napoleón

Leer artículo

¡ES UNA TRAMPA!

En enero de 2021 salió a subasta un manuscrito dictado por el propio Napoleón: sus 74 páginas son una prueba de cuánta planificación hubo destrás de la batalla y de los movimientos militares y diplomáticos que durante meses llevó a cabo el emperador para asegurarse de que sus enemigos actuarían como esperaba. En ello también influyó la suerte y tal vez una cierta improvisación, ya que si no caían en la trampa Napoleón se arriesgaba a encontrarse en inferioridad numérica en territorio austríaco.

El ejército combinado de austríacos y rusos les superaba en número, pero estaba poco cohesionado y carecía de suficientes oficiales preparados para dirigir una fuerza conjunta de tales dimensiones. Napoleón decidió aprovechar esas debilidades y valerse de la estrategia para anular la superioridad numérica, empezando por crear una falsa imagen de debilidad. Mantuvo a parte de sus contingentes separados del cuerpo principal del ejército para que su desventaja pareciera mayor y envió al general Savary a entregar un mensaje al cuartel general de la coalición, expresando su deseo de negociar la paz. Los oficiales rusos y austríacos interpretaron esto como una señal de debilidad inequívoca y propusieron a sus respectivos comandantes lanzar un ataque cuanto antes.

La última parte del plan de Napoleón consistía en atraer a sus enemigos a un terreno favorable. Eligió los Altos de Pratzen, una zona rodeada por colinas cerca de la ciudad de Austerlitz (actual Slavkov u Brna, en la República Checa) y atravesada por estanques que iban a jugar un papel importante en su táctica. El éxito de Bonaparte dependía de que el ejército de la coalición siguiera el plan de acción que había previsto, por lo que debía atraerlo a la vez que evitaba las pérdidas en sus filas.

Plano de la batalla: en azul las fuerzas francesas, en rojo la coalición austro-rusa.

Foto: The Department of History, United States Military Academy (CC)

Su primer movimiento fue lanzar un breve asalto seguido de una retirada para incitar a las fuerzas de la coalición a perseguirle, debilitando a propósito su flanco derecho para asegurarse de que las tropas enemigas avanzaran exactamente por donde a él le convenía. En aquella parte del campo de batalla se encontraban los estanques Satschan, que en aquella época del año estaban cubiertos por el hielo. Cuando las fuerzas aliadas los estaban atravesando, la artillería francesa abrió fuego y rompió el hielo, provocando que muchos soldados se ahogaran en las aguas heladas con sus caballos y hundiendo la artillería enemiga.

Al mismo tiempo, la persecución había debilitado el centro del ejército austro-ruso. El ejército francés atacó con las tropas de reserva que habían permanecido escondidas, apoderándose de las posiciones de la coalición y separando sus dos flancos: el izquierdo se encontró rodeado por los franceses y el derecho, viéndose ahora en inferioridad, emprendió la retirada. En total, las fuerzas de la coalición contaron unas 15.000 bajas entre muertos y heridos.

ARTÍCULO RECOMENDADO

La unificación alemana y el nacimiento del Segundo Reich

Leer artículo

GRANDES REPERCUSIONES

Para la Tercera Coalición aquella fue una derrota muy importante y, sobre todo, inesperada. La peor parte se la llevó el emperador Francisco II del Sacro Imperio: era la segunda gran derrota que sufría en poco tiempo a manos de los franceses, que habían conseguido llegar hasta Viena poco antes del encuentro en Austerlitz. Tuvo que ceder territorios a Francia, a los estados alemanes aliados de Napoleón y al Reino de Italia, un estado satélite cuyo virrey era familiar del propio Bonaparte.

Napoleón dirige sus tropas desde su puesto de mando elevado durante la batalla de Austerlitz.

Ullstein / Cordon Press

Al año siguiente, tras casi mil años de existencia, el Sacro Imperio Romano Germánico se disolvió y en su lugar nació la Confederación del Rin, formada por 16 estados aliados de Bonaparte. El núcleo del poder imperial se reorganizó formando el Imperio Austríaco, a cuya cabeza estaba el propio emperador Francisco: así la dinastía de los Habsburgo-Lorena logró salvar su continuidad, aunque vio reducidos sus dominios, poder y prestigio. La batalla también tuvo un impacto en la credibilidad de Rusia como potencia imperial y en la del zar Alejando I, puesto que la mayoría de bajas fueron entre las tropas rusas.

ARTÍCULO RECOMENDADO

¿Cuánto sabes sobre el imperio napoleónico?

Leer artículo

Por el contrario, la victoria de Napoleón ayudó a reforzar su autoridad como emperador y a consolidar Francia como el gran poder imperial del momento. No obstante, esto también sería la semilla de algunos de los grandes problemas del Imperio Francés en los años venideros: en el norte de Italia los abusos de las tropas napoleónicas dieron inicio a un fuerte sentimiento antifrancés; en los territorios alemanes, Prusia se puso en guardia ante lo que consideraba un desafío directo a su posición dominante en el espacio germánico y se convirtió en el próximo gran enemigo de Francia.

Vista desde la perspectiva histórica, la importancia de Austerlitz no fue solo militar sino también psicológica. El hecho de que Napoleón hubiera vencido a una gran coalición que le superaba ampliamente en número y que lo hubiera hecho valiéndose de la estrategia y aferrándose a un plan tan arriesgado alimentó el mito de su invencibilidad, disuadendo a sus enemigos de intentar oponérsele a corto plazo. Seguramente el propio emperador era consciente de ello, ya que alimentó el relato épico de aquella victoria. Se había cumplido el vaticinio que había hecho al inicio de la batalla: “Un golpe fuerte y la guerra habrá terminado”. Al menos, por un tiempo.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

26 Historic Buildings to Visit the Next Time You’re in Paris

© Corbis

Paris is known today as the City of Lights. Thousands of years ago it was called Midwater-Dwelling—which is how its Latin name, Lutetia, can be translated. This list covers just a few of the most notable structures built in Paris over all of these years.

Earlier versions of the descriptions of these buildings first appeared in 1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die, edited by Mark Irving (2016). Writers’ names appear in parentheses.

-

Notre-Dame de Paris

Notre-Dame de Paris has been the cathedral of the city of Paris since the Middle Ages. It is a Gothic exemplar of a radical change in the Romanesque tradition of construction, both in terms of naturalistic decoration and revolutionary engineering techniques. In particular, via a framework of flying buttresses, external arched struts receive the lateral thrust of high vaults and provide sufficient strength and rigidity to allow the use of relatively slender supports in the main arcade. The cathedral stands on the Île de la Cité, an island in the middle of the River Seine, on a site previously occupied by Paris’s first Christian church, the Basilica of Saint-Étienne, as well as an earlier Gallo-Roman temple to Jupiter, and the original Notre-Dame, built by Childebert I, the king of the Franks, in 528. Maurice de Sully, the bishop of Paris, began construction in 1163 during the reign of King Louis VII, and building continued until 1330. The spire was erected in the 1800s during a renovation by Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, though it was destroyed by fire in 2019.

The western facade is the distinguishing feature of the cathedral. It comprises the Gallery of Kings, a horizontal row of stone sculptures; a rose window glorifying the Virgin, who also appears in statue form below; the Gallery of Chimeras; two unfinished square towers; and three portals, those of the Virgin, the Last Judgment, and St. Anne, with richly carved sculptures around the ornate doorways. The circular rose window in the west front and two more in the north and south transept crossings, created between 1250 and 1270, are masterpieces of Gothic engineering. The stained glass is supported by delicate radiating webs of carved stone tracery. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Hôtel de Soubise

The Hôtel de Soubise is a city mansion built for the prince and princess de Soubise. In 1700 François de Rohan bought the Hôtel de Clisson, and in 1704 the architect Pierre-Alexis Delamair (1675–1745) was hired to renovate and remodel the building. Delamair designed the huge courtyard on the Rue des Francs-Bourgeois. On the far side of the courtyard is a facade with twin colonnades topped by a series of statues by Robert Le Lorrain representing the four seasons.

In 1708 Delamair was replaced by Germain Boffrand (1667–1754), who carried out all the interior decoration for the apartments for the prince’s son, Hercule-Mériadec de Rohan-Soubise, on the ground floor and for the princess on the piano nobile (principal floor), both of which featured oval salons looking into the garden.

The interiors are considered among the finest Rococo decorative interiors in France. In the prince’s salon, the wood paneling is painted a pale green and surmounted by plaster reliefs. The princess’s salon is painted white with delicate gilded moldings and features arched niches containing mirrors, windows, and panels. Above the panels are shallow arches containing cherubs and eight paintings by Charles Natoire depicting the history of Psyche. Plaster rocailles (shellwork) and a decorative band of medallions and shields complete the sweetly disordered effect. At the time of the French Revolution, the building was given to the National Archives. A Napoleonic decree of 1808 granted the residence to the state. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Panthéon

The Panthéon is the quintessential Neoclassical monument in Paris and an outstanding example of Enlightenment architecture. Commissioned as the church of St. Geneviève by King Louis XV, the project has become known as a secular building and a prestigious tomb dedicated to great French political and artistic figures including Mirabeau, Voltaire, Rousseau, Hugo, Zola, Curie, and Malraux, who have been honored and interred in the vaults following the ceremony of Panthéonization.

Jacques-Germain Soufflot (1713–80) was a self-taught architect and tutor to the marquis de Marigny, general director of the king’s buildings, who had been influenced by the Pantheon in Rome. Soufflot claimed that his principal aim was to unite “the structural lightness of Gothic churches with the purity and magnificence of Greek architecture.” His Panthéon was revolutionary: built on the Greek cross plan of a central dome and four equal transepts, his innovation in construction was to use rational scientific and mathematical principles to determine structural formulas for the engineering of the building. This eliminated many of the supporting piers and walls with the result that the vaulting and interiors are slender and elegant. The Neoclassical interior contrasts with the solidity and austere geometry of the exterior. The initial scheme was considered too lacking in gravity and was replaced with a more funereal scheme, which involved blocking 40 windows and destroying the original sculptural decorations. The Panthéon was the location for Léon Foucault’s pendulum experiment to demonstrate the rotation of the Earth in 1851. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Arc de Triomphe

Arc de TriompheNighttime view of the Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

© Corbis

The Arc de Triomphe is one of the world’s largest triumphal arches. Inspired by the Arch of Titus in Rome, it was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1806 after his victory at Austerlitz, to commemorate all the victories of the French army; it has since engendered a worldwide military taste for triumphal and nationalistic monuments.

The astylar design consists of a simple arch with a vaulted passageway topped by an attic. The monument’s iconography includes four main allegorical sculptural reliefs on the four pillars of the Arc. The Triumph of Napoleon, 1810, by Jean-Pierre Cortot, shows an imperial Napoleon, wearing a laurel wreath and toga, accepting the surrender of a city while Fame blows a trumpet. There are two reliefs by Antoine Etex: Resistance, depicting an equestrian figure and a naked soldier defending his family, protected by the spirit of the future, and Peace, in which a warrior protected by Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, is sheathing his sword surrounded by scenes of agricultural laborers. The Departure of the Volunteers of ’92, commonly called La Marseillaise, by François Rude, presents naked and patriotic figures, led by Bellona, goddess of war, against the enemies of France. In the vault of the Arc de Triomphe are engraved the names of 128 battles of the Republican and Napoleonic regimes. The attic is decorated with 30 shields, each inscribed with a military victory, and the inner walls list the names of 558 French generals, with those who died in battle underlined.

The arch has subsequently become a symbol of national unity and reconciliation as the site of the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I. He was interred here on Armistice Day, 1920; today there is an eternal flame commemorating the dead of two world wars. (Jeremy Hunt)

-

Church of St. Mary Magdalene

In 1806 Napoleon commissioned Pierre-Alexandre Vignon, inspector–general of buildings of the Republic, to build a Temple to the Glory of the Great Army and provide a monumental view to the north of Place de la Concorde. Known as ”The Madeleine,” this church was designed as a Neoclassical temple surrounded by a Corinthian colonnade, reflecting the predominant taste for Classical art and architecture. The proposal of the Arc de Triomphe, however, reduced the original commemorative intention for the temple, and, after the fall of Napoleon, King Louis XVIII ordered that the church be consecrated to St. Mary Magdalene in Paris in 1842.

The Madeleine has no steps at the sides but a grand entrance of 28 steps at each end. The church’s exterior is surrounded by 52 Corinthian columns, 66 feet (20 meters) high. The pediment sculpture of Mary Magdalene at the Last Judgment is by Philippe-Henri Lemaire; bronze relief designs in the church doors represent the Ten Commandments.

The 19th-century interior is lavishly gilded. Above the altar is a statue of the ascension of St. Mary Magdalene by Charles Marochetti and a fresco by Jules-Claude Ziegler, The History of Christianity, with Napoleon as the central figure surrounded by such luminaries as Michelangelo, Constantine, and Joan of Arc. (Jeremy Hunt)

https://www.britannica.com/list/26-historic-buildings-to-visit-the-next-time-youre-in-paris |

|

|

|

|

"El hombre que enterró a Hitler": el secreto oculto que cambia el curso de la historia oficial

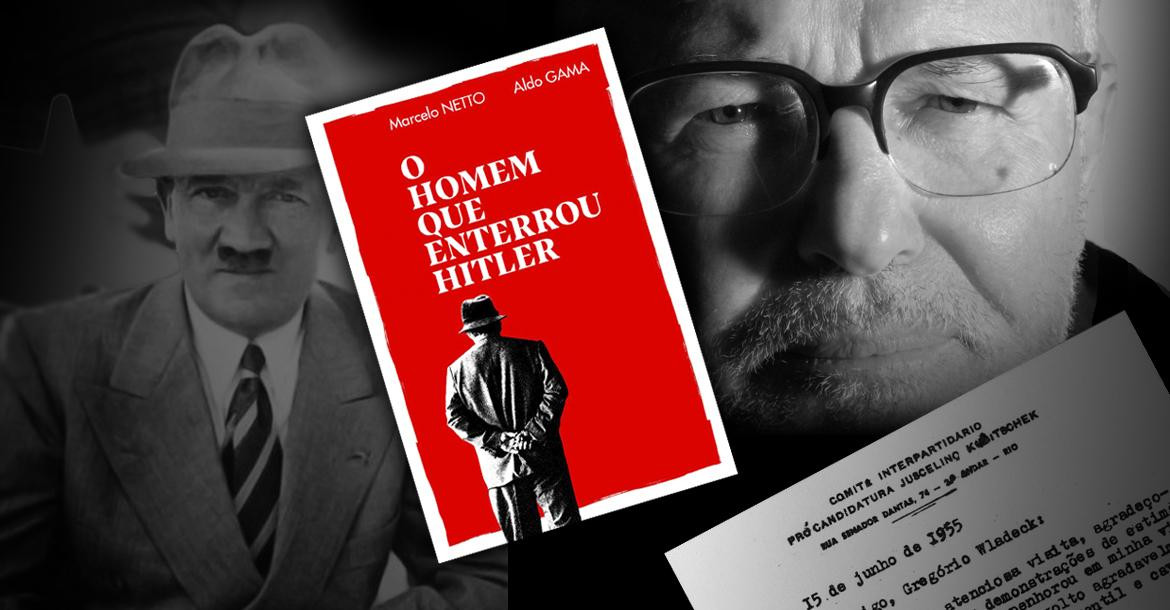

El libro "El hombre que enterró a Hitler" cuestiona la versión histórica oficial de la muerte del líder nazi. La ficción, escrita por los periodistas brasileños Marcelo Netto y Aldo Gama, se basa en una rigurosa investigación que ha llevado 14 años de trabajo, con resultados sorprendentes.

"El hombre que enterró a Hitler" y el "Sr. Fernando", quien activó la investigación. "El hombre que enterró a Hitler" y el "Sr. Fernando", quien activó la investigación.

La historia oficial presentada en libros, documentales y películas sostiene que Adolf Hitler se pegó un tiro en la cabeza el 30 de abril de 1945, días antes de que los soviéticos tomaran Berlín, donde se encontraba el bunker de Hitler. Pero, ¿y si esta versión no es la verdadera?

¿Qué pasaría si Hitler, al darse cuenta de su inminente derrota, hubiera puesto en marcha un plan de escape ya estructurado y, en la oscuridad de la noche del 28 de abril, escapando de Alemania hacia suelo sudamericano y viviendo desapercibido y sin ser molestado durante 26 años?

Te puede interesar:

Donald Trump apuntó contra Kamala Harris a 3 días de las elecciones: "Habla sobre unidad y luego me llama Hitler"

¿Realidad o ficción?

En “El hombre que enterró a Hitler”, Marcelo Netto y Aldo Gama crean una ficción instigadora , que atrapa al lector de la primera a la última línea. Pero, se puede apreciar, a lo largo de la lectura, que la información contenida en el trabajo se basa en una investigación periodística exhaustiva y coherente, realizada por los propios autores. Información que, de ser probada en el futuro (posiblemente inmediato), podría convertirse en una revelación historiográfica sin precedentes. El narrador de la ficción asegura que no ha podido, hasta el final de la obra, probar los hechos mencionados. Pero presenta suficiente riqueza de detalles para provocar en el lector la conocida “pulga detrás de la oreja”, el beneficio de la duda sobre la versión oficial tan repetida a lo largo de la historia. Marcelo Netto, uno de los autores, dice que él y Aldo Gama se decidieron por el género de ficción, y no por un libro-reportaje, precisamente para que la obra no fuera tratada como una teoría de la conspiración, aunque ambos persisten en la investigación de varias pistas contenidas en el texto.

“Realmente no es fácil creer en una versión que va en contra de la esencia de la historia oficial. Deconstruir el sentido común es complicado. Más aún porque hasta ahora no hay pruebas irrefutables que desmantelen la hipótesis de que Hitler se suicidó. Por otro lado, la gente tampoco cuestiona lo contrario, que tampoco hay evidencia de su suicidio. Queremos, con el libro, al menos darle al lector la posibilidad de cuestionar esto”. Según Marcelo Netto, la saga por confirmar que Hitler habría vivido la mayor parte del tiempo en Brasil, Argentina y Paraguay y habría muerto a los 81 años -el 5 de febrero de 1971- ha durado 14 años y continuará. “Estamos a punto de confirmar que un notable jerarca nazi del círculo íntimo de Hitler, que habría huido de Berlín en el mismo avión que él, terminó sus días en São Paulo”, revela.

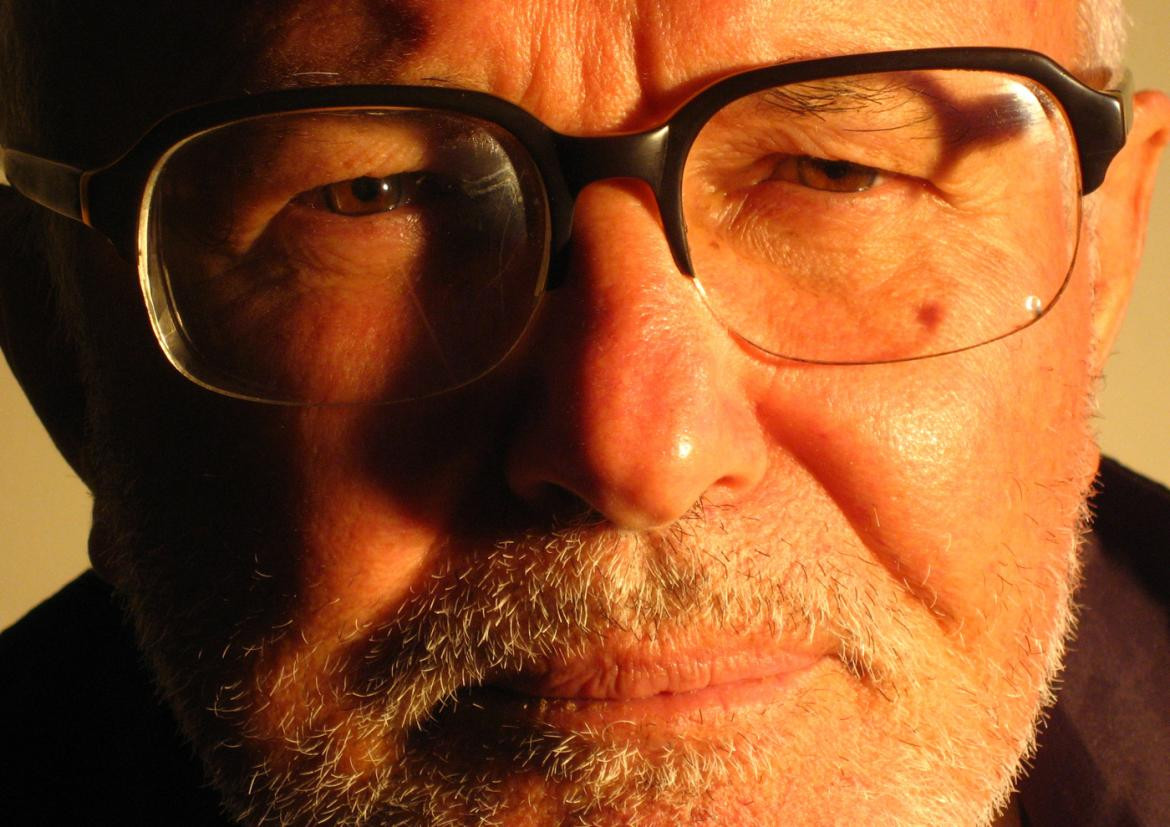

Canal 26 habló en ENTREVISTA EXCLUSIVA con Marcelo Netto, uno de los responsables de la investigación que podría revertir el curso mismo de la historia conocida.

El "Sr. Fernando" reveló detalles del entierro de Hitler en Paraguay. Foto: Jorge Tung. El "Sr. Fernando" reveló detalles del entierro de Hitler en Paraguay. Foto: Jorge Tung.

Canal 26: Marcelo, cuéntenos sobre usted y ¿cómo se vio involucrado en tamaña investigación sobre el entierro de Hitler en Paraguay?

Marcelo Netto: "Soy periodista desde hace 25 años con un máster en Ciencias Sociales. A principios de la década de 2000, trabajé durante un corto período de tiempo para Folha de S.Paulo, considerado uno de los periódicos más prestigiosos de Brasil. Después de unos meses trabajando allí, decidí renunciar al periódico y dejar en suspenso una licenciatura en Ciencias Sociales en la Universidad de São Paulo para vivir con familias del Movimiento de los Sin Tierra. En 2007, cuando ya no vivía en los campamentos y trabajaba para un periódico más pequeño vinculado a los movimientos sociales, un señor vino al periódico para contarnos que había participado en el (segundo) funeral de Hitler en Asunción, Paraguay, el 1 de enero de 1973. Desde entonces, yo y otro amigo periodista (más escéptico que yo) intentamos verificar la historia que nos contó este señor. A lo largo de 14 años, hemos estado cruzando las informaciones con diferentes fuentes y encontrado documentos y vínculos que apoyan considerablemente su testimonio. Es muy difícil llevar adelante este tipo de investigación sin caer en la etiqueta de las teorías de la conspiración. Así que no tuvimos otra opción que contar la historia en una narrativa de ficción".

Canal 26: Como periodista e investigador, comprendo perfectamente lo que es la preservación de la fuente, pero -sin embargo- resulta imposible no preguntarte sobre el informante que activó esta historia. ¿Quién era, cuándo y por qué se presentó a contar esta historia?

Marcelo Netto: "El diferencial de nuestra historia respecto a las demás es que nuestra fuente no nos pide que se preserve su nombre. Además, a diferencia de otros testigos, nos proporciona una dirección concreta donde estaría enterrado Hitler, lo cual también decidimos publicar en el libro. Cuando el "Sr. Fernando" se presenta ante nosotros en mayo de 2007, el Papa Benedicto XVI acababa de terminar su visita a Brasil. El pasado "nazi" de Ratzinger, del que se dice que sirvió a las juventudes hitlerianas, y un comentario de su nieto en el que le preguntaba "por qué él era blanco y no tenía los ojos claros" parecen haber sido los gatillos que faltaban a este sargento retirado del Ejército brasileño para que no se "llevara este secreto al ataúd"".

Marcelo Netto y Aldo Gama, los responsables de la investigación plasmada en el libro. Marcelo Netto y Aldo Gama, los responsables de la investigación plasmada en el libro.

Canal 26: El informante aportó una dirección precisa e -incluso- hizo una descripción del lugar en el que presuntamente se produjo el entierro de Adolf Hitler. Pudo usted constatar la existencia de ese lugar, y ha iniciado gestiones para llegar a demostrar lo relatado?

Marcelo Netto: "Todo comienza cuando buscamos en Google la dirección que nos dio el Sr. Fernando, que, según él, en 1973 se reducía a un césped con un pequeño edículo en el fondo del terreno, pero que albergaba un bunker a tres pisos bajo tierra. Al principio no encontramos nada. Pero entonces buscamos por una “avenida”, después de todo, habían pasado más de 30 años. Y, ¡bingo! No sólo coincidía la dirección, sino que era un hotel alemán, que descubrimos que se había construido sobre el terreno en 2003. Cuando estuvimos en el hotel, nos llamó la atención su "topografía" muy sospechosa. Al entrar y pasar la recepción, es necesario bajar unos escalones (haciendo que el suelo esté un poco por debajo del nivel de la calle). La cocina, que pudimos ver a través de una ventana mientras caminábamos por el pasillo principal, estaba aún más abajo, prácticamente en el sótano. Algunas habitaciones del hotel rodean un "jardín de invierno" al aire libre con algunas palmeras. Pensamos: "si el búnker está aquí abajo, esta es la razón por la que, en 2003, no pudieron construir habitaciones sobre el césped que el señor Fernando dice haber encontrado 30 años antes, en 1973. Lo mismo ocurre con el propio búnker de Hitler en Berlín, que hoy está escondido bajo un estacionamiento...". También nos llamó la atención el hecho de que la casa vecina, al fondo de un gran estacionamiento abierto literalmente junto al jardín de invierno del hotel, aunque separada por un muro, es una especie de "residencia de ancianos" con enfermeras que van y vienen. ¿Podría haber sido aquí donde los “kameraden” de Hitler en la vejez los llevaron cuando se construyó el hotel? Esto porque el señor Fernando también comenta que en el búnker, durante el funeral, había unos tantos alemanes que parecían ser jerarcas nazis en silla de ruedas. Dicho esto, no hay manera de no plantear la pregunta: “¿No hay nada construido en su superficie precisamente por el búnker que hay debajo?”. Añadido a esto, recientemente nos enteramos por otra fuente (que hasta entonces no conocía nuestra historia) que el "búnker de Hitler en Asunción" se encuentra justo bajo un estacionamiento…"

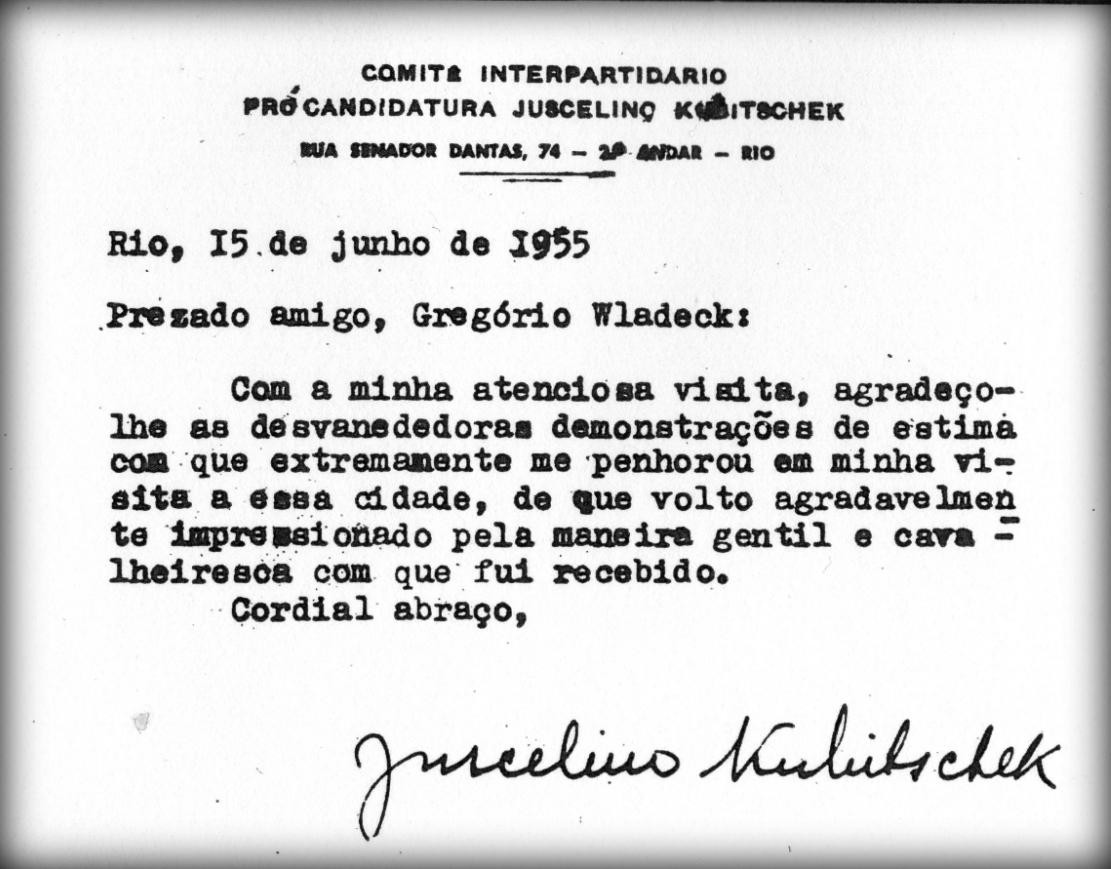

Canal 26: ¿Y cómo decidió embarcarse en esta aventura, convertido casi en un Quijote contra los molinos de viento de la historia oficial?

Marcelo Netto: "Dos hechos me animaron a no abandonar, además de que la dirección resultó ser la de un hotel alemán. A finales de 2008, unos dos años después de que empezáramos a investigar, lo que se consideraba la "prueba más concreta" de la muerte de Hitler se vino abajo. Una prueba de ADN reveló que su supuesto cráneo conservado durante años por los soviéticos, ahora rusos, es en realidad de una mujer, de unos 40 años. Otro momento emblemático fue que, tras años de búsqueda, encontramos un documento de la Municipalidad de Asunción que demuestra que el hotel es, de hecho, propiedad de la misma asociación germano-paraguaya que nuestra fuente nos había dicho que era dueña del terreno cuando estuvo allí en 1973 para asistir al (segundo) funeral de Hitler. Y, más aún, haber logrado identificar su relación directa con una colonia alemana, a 80 km de Asunción, que fue la sede de la fundación del Partido Nazi en Paraguay en 1928, uno de los primeros partidos, si no el primero, fuera de Alemania. En el caso de Aldo Gama, que suele decir que, como todo buen Sancho Panza, abrazó la causa "con toda la dedicación que permite el cinismo", no se trató de una transformación inmediata, sino del zumbido del rompecabezas que muestra una imagen cuando las piezas encajan. Si tuviéramos que elegir un momento, un clímax, para él, creo que fue una especie de postal de Juscelino Kubitscheck que descubrimos por casualidad al analizar un montón de documentos en una biblioteca de un instituto alemán en São Paulo. Nuestra fuente dice que Juscelino sabía de la presencia de Hitler en el país y que había enviado un general brasileño muy famoso en la época, el general Lott, a la ciudad donde se encontraba la colonia alemana en la que se escondía Hitler para darle un ultimátum. La postal demuestra que Juscelino estaba allí al mismo tiempo. Lo que nos lleva a preguntarnos: “qué estaría haciendo Juscelino en una ciudad prácticamente insignificante para su campaña electoral?” Resulta que el cambio es gradual. Un documento aquí, una declaración allí, una foto... De repente, lo imposible se convierte en improbable, lo que acaba convirtiéndose en una posibilidad."

Nota de Juscelino Kubitscheck. 15 de junio de 1955. Nota de Juscelino Kubitscheck. 15 de junio de 1955.

Canal 26: Hasta el momento ¿qué datos pudo efectivamente comprobar y demostrrar de los hechos relatados?

Marcelo Netto: "El libro traza una gigantesca tela de araña que toma forma a través de una interconexión de datos procedentes de diferentes fuentes que nunca han estado en contacto. La declaración del Sr. Fernando, para nosotros, es sólo un punto de partida, el "hilo de Ariadna" y desde el principio nos cuidamos de no asumir que lo que nos dice es verdad. Más aún porque es un personaje muy peculiar, lo que puede llevar a algunos a descartar su historia inmediatamente, sin darse cuenta de que él sigue el mismo patrón de los testigos que dicen haber estado con Hitler después de su supuesto suicidio. En otras palabras, es siempre la empleada de la gasolinera, la criada, el carpintero. Al final, la verdad no sale a la luz más rápido porque nadie se toma en serio la historia de la "gente sencilla", cuando debería ser exactamente lo contrario. Frente a ellos, todos los cuidados son dejados de lado por los nazis que lograron escapar, porque suponen que los "sirvientes" ni siquiera los conocen o porque están seguros de que, además de ser ridiculizados si abren la boca, no tienen poder para hacer nada. Al fin y al cabo, ¿quién les va a hacer caso? Digamos que al menos no hay ninguna incoherencia flagrante que desacredite la historia que el Sr. Fernando nos cuenta, probada a lo largo de 14 años de investigaciones y chequeos. Así que estamos bastante convencidos de que su historia sea verídica. Más aún, en esta misma lógica de seguir el "hilo de Ariadna" que el Sr. Fernando sostiene fuertemente en sus manos, estamos por confirmar que uno de los jerarcas que habría escapado con Hitler de Berlín en la noche del 28 de abril y que, según la historia, murió esa misma noche, en realidad, terminó sus días, ya centenario, en un barrio alejado de la ciudad de de San Pablo, Brasil. El inicio de esta investigación, que sigue en curso, también forma parte del libro."

Canal 26: ¿A qué inconvenientes debió enfrentarse en el curso de esta investigación hoy plasmada en el libro "El hombre que enterró a Hitler"?

Marcelo Netto: "Lo más difícil siempre fue conseguir que quienes escuchaban la historia de nuestra boca de primera mano superaran la "verdad" de que Hitler se suicidó en el búnker, -incluso sin la existencia de un cadáver o de testigos, para poder separar el trigo de la paja de las conspiraciones- y decir que teníamos suficientes pruebas para creer en la historia de un hombre que nos contactó en 2007. A lo largo del camino, hablamos con muchas personas públicas. Incluso nos encargamos de que la información llegara al entonces presidente Fernando Lugo, de Paraguay, a través de su asesor directo cuando estuvimos en Asunción para entrevistar a Lugo sobre otros asuntos. Esto fue apenas unas semanas antes del golpe parlamentario contra él. También tuvimos contacto con algunas productoras. Incluso un contacto más personal con el cineasta Walter Salles, mundialmente famoso por "Estación Central" y "Diarios de motocicleta", que nos ayudó económicamente con parte de la investigación... Después de algunos años insistiendo, la idea del documental se fue alejando. Pero ahora, con la publicación del libro, está más vivo que nunca."

Aldo Gama, co autor de la investigación plasmada en el libro, dice que todo comenzó por cuenta de Marcelo Netto, quien siempre creyó en el relato de su fuente. Aldo dice que, al principio, no le interesaba el tema, principalmente porque estaba convencido de que la versión oficial era la única posible. “Como un Sancho Panza involuntario, terminé persiguiendo este molino por diversión y porque entendí desde el primer momento que era una historia de ficción espectacular. Como la realidad es más absurda que cualquier imaginación, acabé encontrando hechos históricos tan inverosímiles como espectaculares ”, dice.

“Pero mi conversión completa comenzó con un descubrimiento del tipo que solo el azar o la terquedad pueden proporcionar: estaba dormido un domingo por la mañana, escondido en una biblioteca por lealtad al Quijote, y encontré una nota que probaba varias acusaciones en el testimonio. Eso había comenzado todo. Entonces tenía un documento histórico irrefutable que, si no lo probaba, hacía posible la cadena de hechos que perseguíamos”, sigue.

Según Aldo, “por discreción y un poco de burla”, decidieron no aclarar dónde comienza y termina la ficción. “Para el ojo atento, es evidente y no estamos aquí para incentivar la pereza del lector. Hablando Paulocoelhamente, quien busca lo encontrará. Pero prepárate para que el viaje esté lleno de aventuras y el camino esté lleno de baches. ¡Buen batido!"

Por razones directamente relacionadas con el curso de la investigación, y por estrictas medidas de seguridad y confidencialidad, hasta que el lugar sea abierto e inspeccionado por la Justicia, se ha omitido -de manera deliberada- mencionar el nombre y la dirección del hotel en donde se encuentra la cripta funeraria de Adolf Hilter en Paraguay.

"El hombre que enterró a Hitler" (O homen que enterrou Hitler"), Marcelo Netto y Aldo Gama, EditoraContracorrente, Brasil, 2021.

Instagram: @marcelo.garcia.escritor

Notas: El artículo no expresa ideología política, solo investigación histórica.

https://www.canal26.com/historia/el-hombre-que-enterro-a-hitler-el-secreto-oculto-que-cambia-el-curso-de-la-historia-oficial--311088

|

|

|

|

|

Earth from Space – Arc de Triomphe, Paris

Status Report

May 13, 2022

Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

ESA

This striking, high-resolution image of the Arc de Triomphe, in Paris, was captured by Planet SkySat – a fleet of satellites that have just joined ESA’s Third Party Mission Programme in April 2022.

The Arc de Triomphe, or in full Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, is an iconic symbol of France and one of the world’s best-known commemorative monuments. The triumphal arch was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1806 to celebrate the military achievements of the French armies. Construction of the arch began the following year, on 15 August (Napoleon’s birthday).

The arch stands at the centre of the Place Charles de Gaulle, the meeting point of 12 grand avenues which form a star (or étoile), which is why it is also referred to as the Arch of Triumph of the Star. The arch is 50 m high and 45 m wide.

The names of all French victories and generals are inscribed on the arch’s inner and outer surfaces, while the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I lies beneath its vault. The tomb’s flame is rekindled every evening as a symbol of the enduring nature of the commemoration and respect shown to those who have fallen in the name of France.

The Arc de Triomphe’s location at the Place Charles de Gaulle places it at the heart of the capital and the western terminus of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées (visible in the bottom-right of the image). Often referred to as the ‘most beautiful avenue in the world’, the Champs-Élysées is known for its theatres, cafés and luxury shops, as the finish of the Tour de France cycling race, as well as for its annual Bastille Day military parade.

This image, captured on 9 April 2022, was provided by Planet SkySat – a fleet of 21 very high-resolution satellites capable of collecting images multiple times during the day. SkySat’s satellite imagery, with 50 cm spatial resolution, is high enough to focus on areas of great interest, identifying objects such as vehicles and shipping containers.

SkySat data, along with PlanetScope (both owned and operated by Planet Labs), serve numerous commercial and governmental applications. These data are now available through ESA’s Third Party Mission programme – enabling researchers, scientists and companies from around the world the ability to access Planet’s high-frequency, high-resolution satellite data for non-commercial use.

Within this programme, Planet joins more than 50 other missions to add near-daily PlanetScope imagery, 50 cm SkySat imagery, and RapidEye archive data to this global network.

Peggy Fischer, Mission Manager for ESA’s Third Party Missions, commented, “We are very pleased to welcome PlanetScope and SkySat to ESA’s Third Party Missions portfolio and to begin the distribution of the Planet data through the ESA Earthnet Programme.

“The high-resolution and high-frequency imagery from these satellite constellations will provide an invaluable resource for the European R&D and applications community, greatly benefiting research and business opportunities across a wide range of sectors.”

To find out more on how to apply to the Earthnet Programme and get started with Planet data, click here.

– Download the full high-resolution image.

|

|

|

|

|

El Arco de Triunfo de París (en francés: Arc de Triomphe o Arc de Triomphe de l'Étoile) es uno de los monumentos más famosos de la capital francesa y probablemente se trate del arco de triunfo más célebre del mundo. Construido entre 1806 y 1836 por orden de Napoleón Bonaparte para conmemorar la victoria en la batalla de Austerlitz, está situado en el VIII Distrito de París, sobre la plaza Charles de Gaulle, antiguamente denominada plaza de la Estrella (en francés: Place de l’Étoile), en el extremo occidental de la avenida de los Campos Elíseos, a 2,2 km de la plaza de la Concordia, ubicada en el extremo oriental de dicha avenida. Tiene una altura de 50 m, un ancho de 45 m y una profundidad de 22 m. La bóveda grande mide 29,19 m de alto por 14,62 m de ancho, mientras que la pequeña mide 18,68 m de alto por 8,44 m de ancho. Es gestionado por el Centro de los monumentos nacionales.2 |

|

|

|

|

Earth from Space – Arc de Triomphe, Paris

Status Report

May 13, 2022

Arc de Triomphe, Paris.

ESA

This striking, high-resolution image of the Arc de Triomphe, in Paris, was captured by Planet SkySat – a fleet of satellites that have just joined ESA’s Third Party Mission Programme in April 2022.

The Arc de Triomphe, or in full Arc de Triomphe de l’Étoile, is an iconic symbol of France and one of the world’s best-known commemorative monuments. The triumphal arch was commissioned by Napoleon I in 1806 to celebrate the military achievements of the French armies. Construction of the arch began the following year, on 15 August (Napoleon’s birthday).

The arch stands at the centre of the Place Charles de Gaulle, the meeting point of 12 grand avenues which form a star (or étoile), which is why it is also referred to as the Arch of Triumph of the Star. The arch is 50 m high and 45 m wide.

The names of all French victories and generals are inscribed on the arch’s inner and outer surfaces, while the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier from World War I lies beneath its vault. The tomb’s flame is rekindled every evening as a symbol of the enduring nature of the commemoration and respect shown to those who have fallen in the name of France.

The Arc de Triomphe’s location at the Place Charles de Gaulle places it at the heart of the capital and the western terminus of the Avenue des Champs-Élysées (visible in the bottom-right of the image). Often referred to as the ‘most beautiful avenue in the world’, the Champs-Élysées is known for its theatres, cafés and luxury shops, as the finish of the Tour de France cycling race, as well as for its annual Bastille Day military parade.

This image, captured on 9 April 2022, was provided by Planet SkySat – a fleet of 21 very high-resolution satellites capable of collecting images multiple times during the day. SkySat’s satellite imagery, with 50 cm spatial resolution, is high enough to focus on areas of great interest, identifying objects such as vehicles and shipping containers.

SkySat data, along with PlanetScope (both owned and operated by Planet Labs), serve numerous commercial and governmental applications. These data are now available through ESA’s Third Party Mission programme – enabling researchers, scientists and companies from around the world the ability to access Planet’s high-frequency, high-resolution satellite data for non-commercial use.

Within this programme, Planet joins more than 50 other missions to add near-daily PlanetScope imagery, 50 cm SkySat imagery, and RapidEye archive data to this global network.

Peggy Fischer, Mission Manager for ESA’s Third Party Missions, commented, “We are very pleased to welcome PlanetScope and SkySat to ESA’s Third Party Missions portfolio and to begin the distribution of the Planet data through the ESA Earthnet Programme.

“The high-resolution and high-frequency imagery from these satellite constellations will provide an invaluable resource for the European R&D and applications community, greatly benefiting research and business opportunities across a wide range of sectors.”

To find out more on how to apply to the Earthnet Programme and get started with Planet data, click here.

– Download the full high-resolution image.

|

|

|

|

|

| Foundation stone. On August 15, 1806, Emperor Napoleon I's birthday, the foundation stone of the building was laid at a depth of eight meters, between the two southern pillars. |

|

|

|

|

| Enviado: 21/10/2024 10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Para otros usos de este término, véase Austerlitz.

|

|

|

|

|

| Battle of Austerlitz |

| Part of the War of the Third Coalition |

Battle of Austerlitz, 2 December 1805, romanticized painting by French artist François Gérard, c. 1810 |

|

|

| Belligerents |

|

French Empire French Empire

|

|

| Commanders and leaders |

|

|

|

| Units involved |

|

|

|

| Strength |

| 65,000–75,000[a] |

73,000–89,000[b] |

| Casualties and losses |

- Total: 8,852

- 1,288 killed

- 6,991 wounded

- 573 captured[7]

|

- Total: 27,000–36,000

- 15,000–16,000 killed or wounded[7]

- 12,000–20,000 captured[7]

|

|

|

|

|

|

Primeira Primeira

Anterior

9 a 23 de 23

Seguinte Anterior

9 a 23 de 23

Seguinte

Última

Última

|

|

| |

|

|

©2026 - Gabitos - Todos os direitos reservados | |

|

|