Paris is one the most visited cities in the world, with no shortage of landmarks and history. But what may not be apparent to visitors to Paris is that there is a specific logic to how the city is laid out, with some of the most famous monuments of the city placed on an important axis.

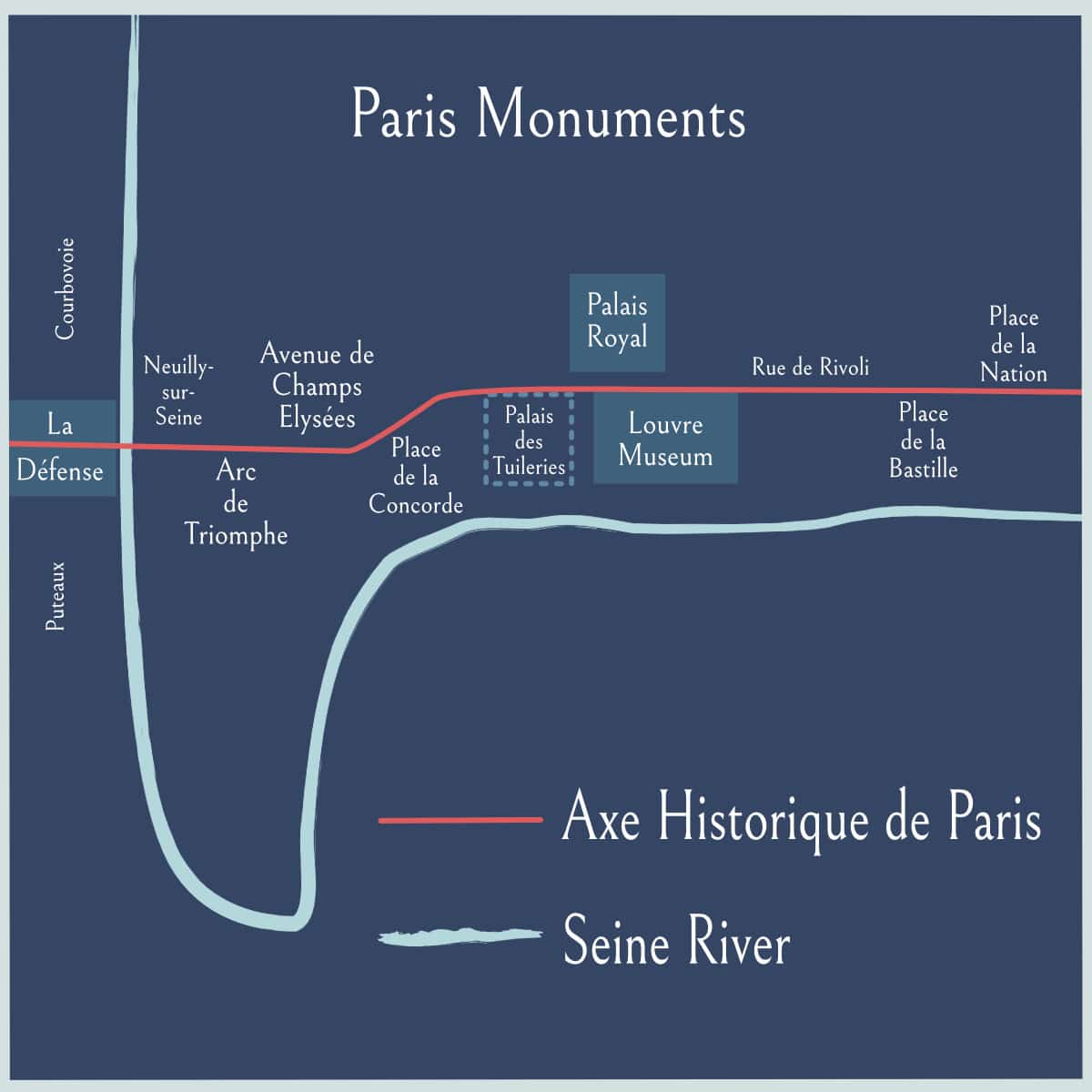

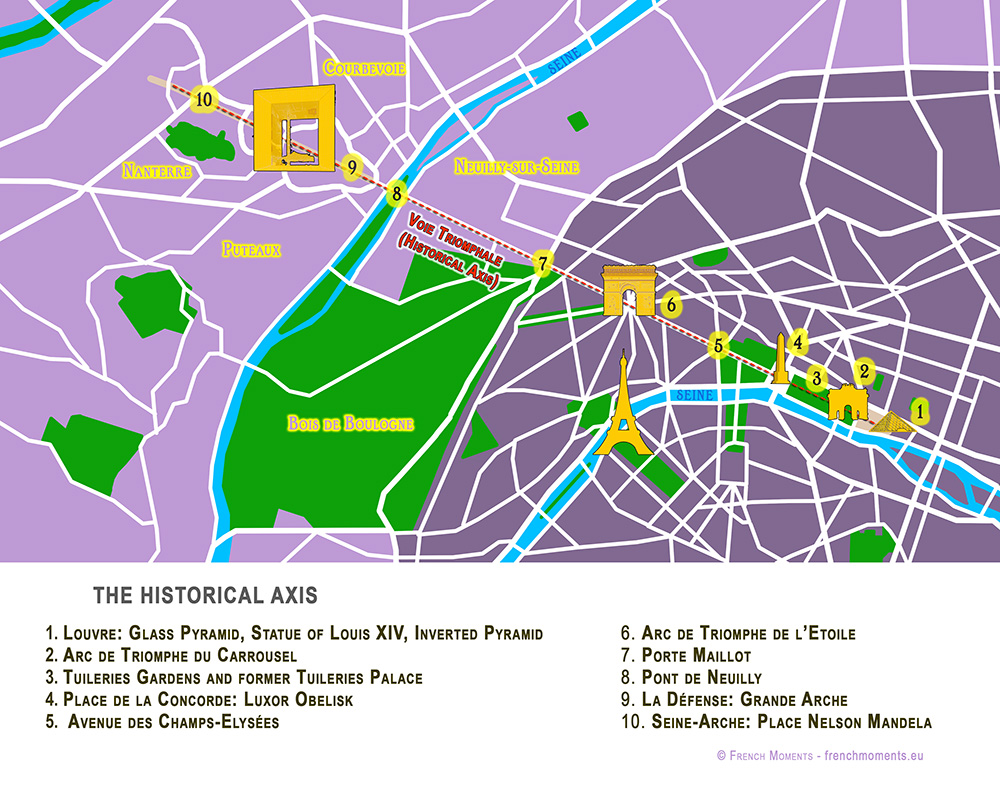

The Axe historique de Paris ( meaning “historic axis of Paris”) is a line of monuments and buildings along a series of broad avenues that extends from the center of Paris to the west. It is based on the old “Voie Triomphale” or “Triumphal Way”, an old historic Roman road that existed in Italy.

Today, along with Metro line 1, the historic axe of Paris informally encompasses the east side as well. There is a slight bend in the line to trace the line of the Seine River that flows alongside.

The line of monuments trace the history of the city of Paris, from its initial beginnings, traumatic revolutions, and wars to the modern city that it is today.

Many of the wide thoroughfares that connect the monuments date back to the 1860s when Baron Haussmann reimagined Paris’s architecture to improve the flow of carriage traffic, and movement of goods and people. So let’s explore the Axe historique of Paris, shall we? Allons-y!

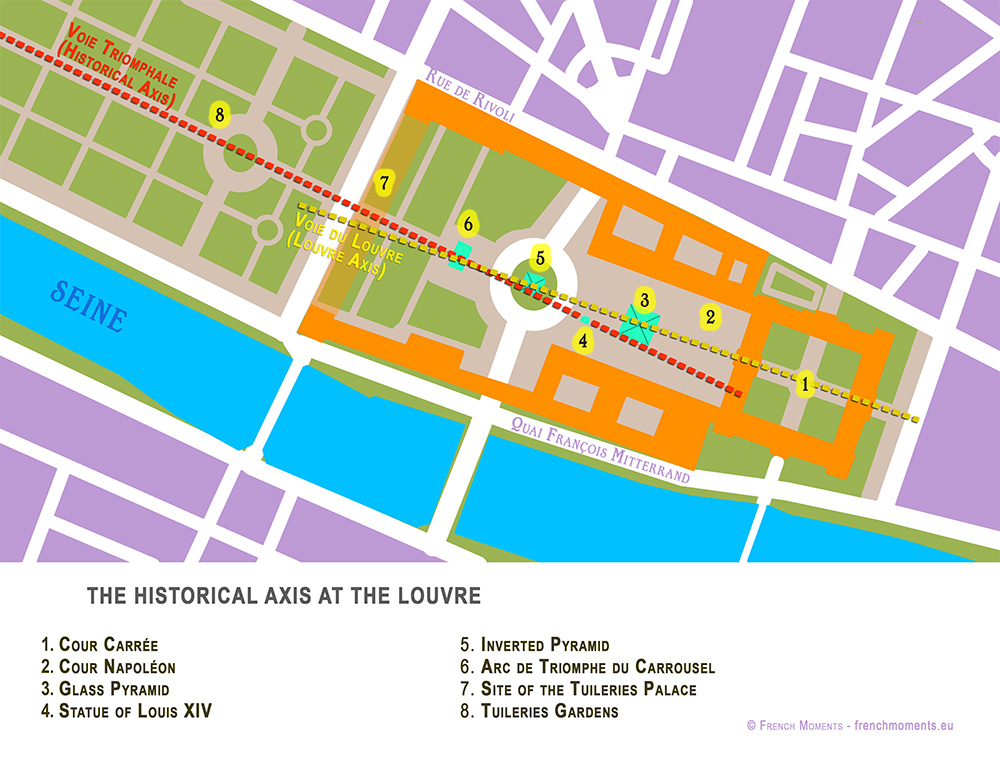

1. Palais du Louvre

In the heart of the 1st arrondissement of Paris is the Louvre Museum, the world’s largest art museum, and a UNESCO historic monument.

The fortress that became the Chteau du Louvre was initially built in 1190 French King Louis Auguste. Its location on the Right bank of the Seine river was across from the older part of Paris, which was formerly called Lutece (today Ile de la Cité and the Latin quarter in the 5th arrondissement).

This was the center for the Frankish kings, eventually settling outwards in the Ile-de-France.

Miniature painting of the Palais du Louvre, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Courtesy of Wikipedia

Miniature painting of the Palais du Louvre, from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry. Courtesy of Wikipedia

Subsequent kings during the Middle ages would expand the fortress, using the Louvre as a royal residence, a prison, a place for keeping the treasury, and even for a library, before finally becoming a museum. You can read more the history of the Palais du Louvre here.

Today it holds everything from paintings like Mona Lisa to sculptures by Michaelangelo. There is just not enough time to see the 35,000 pieces of art that are on display at the Louvre.

Many of the works were placed there by French Kings and Queens throughout history, including Napoleon Bonaparte who set off pillaging various artworks across Europe. Acquisitions were made of Spanish, Austrian, Dutch, and Italian works, either as the result of war looting or formalized by treaties.

With objects ranging from Egyptian antiquities to European art, the Lourve museum has to be on the bucket list of any first-time vistor to Paris. If you do plan on visiting the Louvre, you can read more about the works of art you shouldn’t miss at the Louvre here.

Note: During the busy summer season, tickets often are only sold online for timed entrances. Book in advance to avoid disappointment.

2. Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel

Directly in the courtyard of the Louvre is the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel that was commissioned by Napoleon to commemorate his military victories (along with the “other” Arc de Triomphe on the Champs Elysées).

Initially, on top of the Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel were placed the Horses of Saint Mark. They had adorned the Basilica of San Marco in Venice since the sack of Constantinople in 1204 and had been brought to Paris where they were placed atop Napoleon’s Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel.

After Napoleon Bonaparte’s defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, many of the countries he had previously conquered asked for their artwork back. The Horses of Saint Mark were returned to Italy and today there is a copy on top instead.

3. Palais des Tuileries

Directly next to the Louvre Museum is the Jardin des Tuileries. This was once the site of a historic royal palace, the Palais des Tuileries, and it is in this palace that Marie-Antoinette, Louis XVI and their children were brought to after being forced to leave Versailles.

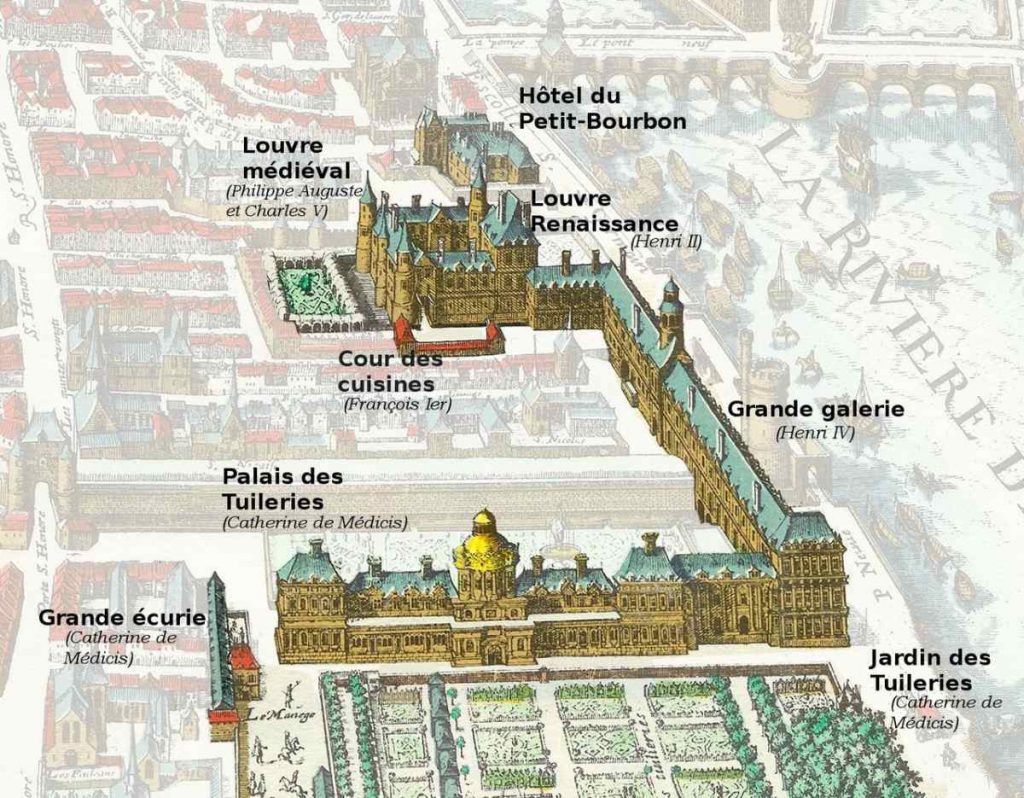

Louvre Palace in 1615 – Courtesy of XIII Wikipedia

Louvre Palace in 1615 – Courtesy of XIII Wikipedia

French Queen Catherine de Medici started building the Palais des Tuileries two centuries earlier in 1564, a stone’s throw away from the Palais du Louvre. Later monarchs would go on to add wings and attach the Tuileries and the Louvre.

After several revolutions, it was burnt down during the Paris Commune protests in 1871. Portions of attached Louvre were also destroyed, but were saved by the efforts of Paris firemen and museum employees. The Tuileries Palace however, was destroyed.

Today, it is a large expansive garden, the “backyard” of locals living in this part of the Right bank. Entry to the gardens is Free.

Right across from the Jardin des Tuileries is the Palais-Royal which is today a series of government offices. It consists of several buildings which are interconnected, with a foreground courtyard, and a larger garden courtyard all within the premises.

And within the inner courtyard Cour d’Honneur of the Palais Royal in Paris is the art installation by Daniel Buren, called the Colonnes de Buren. Tourists cannot visit inside Palais Royal, but you can read more about it here.

4. Place de la Bastille

Directly to the east of the Louvre Museum along a large boulevard is the epicenter of the French Revolution.

The Place de la Bastille is where the ancient prison called Bastille Saint-Antoine was located before it was destroyed. The original old fort was built at Bastille between 1370 and 1383 during the reign of King Charles V to protect the east end of Paris along the Seine.

Place de la Bastille, Paris

Place de la Bastille, Paris

The fortress was declared a state prison in 1417, and its dungeons and cells continued to be used as a prison for important political prisoners until the revolution, including the “Man in the Iron Mask”.

On July 14, 1789 the revolutionaries stormed into the Bastille, freeing all the prisoners and beheading the prison’s governor and stuck his head on a spike. The revolution had begun and soon spread all across Paris and the rest of France.

Some of the stones from the prison at Bastille were used to build to the Pont de la Concorde that leads from the Place de la Concorde to the Assemblée Nationale (France’s House of Representatives) which is in the 7th arrondissement.

5. Place de la Concorde

In a straight thoroughfare from the Place de la Bastille, past the Louvre Museum, is the Place de la Concorde in the 8th arrondissement and its towering Egyptian obelisk.

This marks the spot where Marie-Antoinette, King Louis XVI and other members of French nobility had their heads guillotined during the French Revolution.

If you are interested in is era, follow my self-guided walking Revolution tour. These days, the Place de la Concorde is a giant roundabout, with a fountain in the middle and the American Embassy next to it.

6. Avenue de Champs Elysées

The famed Champs Elysées may today be known better as a shopping street, but it has also historically been the street that has seen the conquering armies of Napoleon Bonaparte, Prussians, Hitler, and the Allied army parade celebrations at the end of WWII.

Famous victory marches around or under the Arc de Triomphe include:

- the Germans in 1871 – Franco-Prussian war

- the French in 1919 – WWI

- the Germans in 1940 – the invasion of France at start of WWII

- French and Allied Forces in 1944-45 – end of WWII

Nowadays, there are military marches every 14 Juillet (Bastille Day) and 11 November (Armistice day) where the President of France and other dignitaries gather with flags to pay tribute to those who have fought for the country’s freedoms.

Within a few 100 yards of the Champs Elysées is the official residence of the President of France. It only open to tourists on Journée du Patrimoine in each September, but you can read more about my visit to the incredible Palais de l’Elysée here.

7. Arc de Triomphe

The Arc de Triomphe is one of the most symbolic monuments in France, with the unknown soldier buried at its base, along with the eternal flame.

Both the Arc de Triomphe on the Champs Elysées, as well as a 2nd one that is standing in front of the Louvre, were commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1806 to commemorate his victories.

Arc de Triomphe at the west end of the Champs Elysées

Arc de Triomphe at the west end of the Champs Elysées

His defeat by the British meant that he never saw it finished. It was finally completed in 1836, and become a rallying point for both French and foreign armies.

You can climb up to the top of the Arc de Triomphe and bow to the tomb of the Unknown Soldier and the Eternal Flame. Lines are long so buy your tickets to the Arc de Triomphe here.

8. La Défense

In a straight line from the Arc de Triomphe is a new modern “Arch” made of glass and concrete.

From a distance, the Grand Arch de la Défense looks likes it belongs in a modern North American city. Essentially this area came about in the 1950s when the decision was made that no one wanted these large office buildings within Paris intra-muros to spoil the look of all those lovely 18-century Hausmannian buildings.

Grand Arch de la Défense

Grand Arch de la Défense

It was decided then, to construct those new office towers in an area west of Paris. This new business area would be placed along the Axe Historique de Paris, showing the movement from Old World to the New Industry.

The new business district was built in the department of Hauts-de-Seine, but is still part of the Grand Paris region. Today, Place de la Défense is a hub for multinational corporations and is considered the largest business district in Europe, with the highest concentration of offices.

9. Place de la Nation

Although technically not part of the Axe historique de Paris, the Place de la Nation on the east end also follows the straight line of Metro Line 1 from Place de la Bastille.

Once outside of Paris, this was part of the old village of Pique-Puce (Picpus). A throne was installed here in 1660 for the solemn entry into Paris of King Louis XIV and Marie-Thérèse of Austria after their marriage in Saint-Jean-de-Luz, giving it the name “Place du Trône”, meaning “Place of the throne”.

It would be renamed “Place du Trône-Renversé”, meaning Place of the tossed over throne” during the French Revolution, eventually becoming absorbed into Paris and becoming the “Place of the Nation”.

These days, it has become a symbolically important square in Paris, where protests and other gatherings often start or end.

Read more:

Flip

Flip

![Sunset under the Arc de Triomphe © Siren-Com - licence [CC BY-SA 3.0] from Wikimedia Commons](https://frenchmoments.eu/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Sunset-Arc-de-Triomphe-%C2%A9-Siren-Com-licence-CC-BY-SA-3.0-from-Wikimedia-Commons.jpg)