LAST UPDATED: 29 MAY 2024

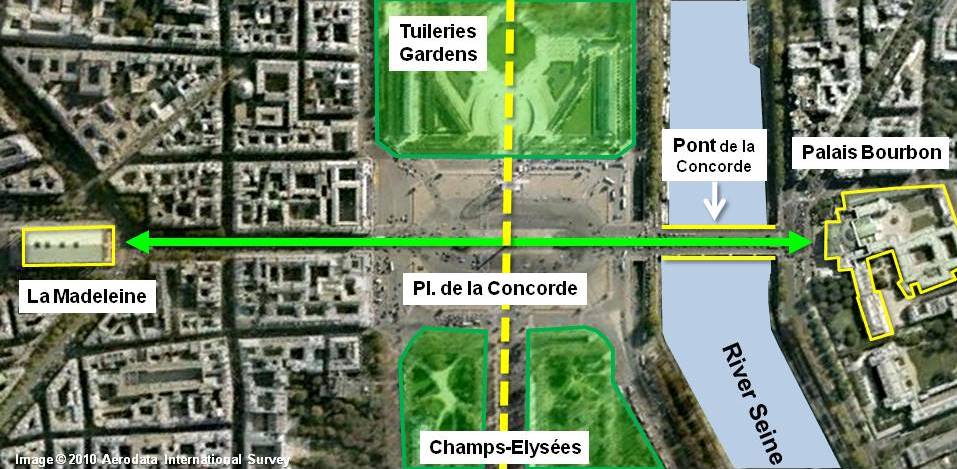

The majestic Place de la Concorde played an essential part in French history. On many occasions, the square has been chosen for happy or sad national gatherings. One of the many prestigious stages of the Historical Axis, the square features a vast and elegant neo-classical ensemble from the 18th century. It connects the Tuileries Garden to the Champs-Elysées and the Madeleine to Palais Bourbon.

The magnificence of place de la Concorde

The Place de la Concorde plays a significant symbolic part along the Historical Axis. This magnificent vista runs through some of Paris’ most celebrated monuments and squares:

Fountain of the Rivers on Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Fountain of the Rivers on Place de la Concorde © French Moments

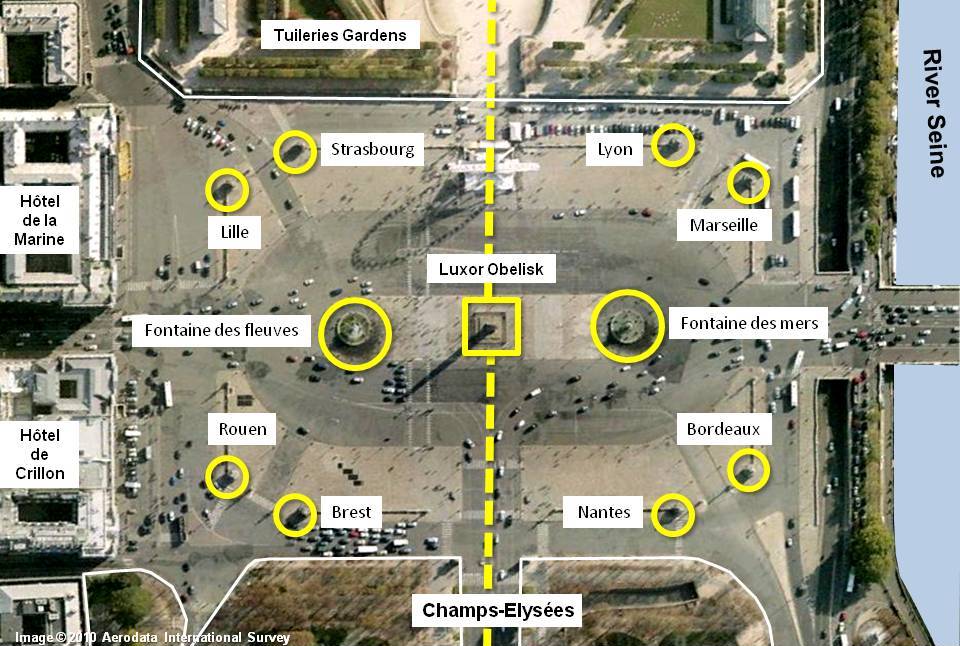

The square takes the form of an octagon measuring 359 by 212 metres. The River Seine borders it to the South, and classical-style buildings to the North. The Egyptian obelisk stands at the centre of the square, flanked by two massive fountains.

The turbulent history of the square

In 1753 it was decided that the site should be designed as a square. This decision was taken during the reign of King Louis XV. At that time, many French cities had started or completed prestigious squares. They were commonly called “Place Royale” to the glory of the King: Montpellier, Nantes, Metz, Dijon or Bordeaux.

For instance, in the then-independent Duchy of Lorraine, the King’s father-in-law, Stanislas Leszczyński, commissioned the beautiful Place Stanislas in Nancy, which was well underway by 1753.

Place Stanislas, a royal square in Nancy built in 1753-1755 © French Moments

Place Stanislas, a royal square in Nancy built in 1753-1755 © French Moments

A grand square dedicated to Louis XV

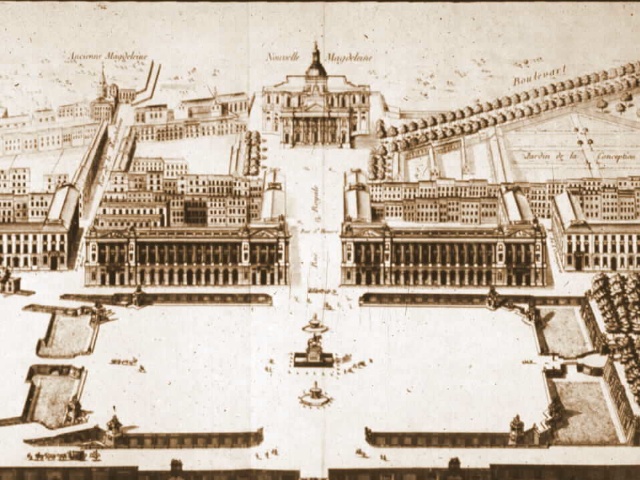

Gabriel, the King’s architect, was tasked with creating a magnificent square along the Historical Axis. It would stage an equestrian statue of Louis XV in the centre. The two monumental pavilions bordering the square’s northern side and divided by the Rue Royale were built in the Louis XV style: the Hôtel Crillon and the Hôtel de la Marine.

Plan of Gabriel for the Louis XV Square © French Moments

Plan of Gabriel for the Louis XV Square © French Moments

The tragic event of 30 May 1770

Misfortune struck the square on the occasion of the marriage of Dauphin Louis and Austrian archduchess Marie-Antoinette. On the 30th May 1770, people assembled for a celebration with much pomp and ceremony. A beautiful firework display was planned. However, following the accidental fall of a rocket, the crowd was panic-stricken, and 133 people were killed, trampled and choked.

During the Reign of Terror

But the worst was yet to come 20 years later with the uprising of the Revolution. Originally called ‘Place Louis XV’, the square was renamed in 1792 as ‘Place de la Révolution’. It became the stage for horrendous public executions by the guillotine.

During the Reign of Terror, the King, Queen Marie-Antoinette, and more than 1,100 victims were beheaded in less than two and a half years.

Execution of Louis XVI on Place de la Concorde

Execution of Louis XVI on Place de la Concorde

On 21st January 1793, Louis XVI was guillotined at the exact position of the statue of Brest, at the North-West angle.

The monument of Brest, the spot where the guillotine was placed for Louis XVI’s execution © French Moments

The monument of Brest, the spot where the guillotine was placed for Louis XVI’s execution © French Moments

From the 13th of May 1793, the “National Razor” was moved across the square near the railings of the Tuileries Gardens. Many more victims were beheaded: Marie-Antoinette (16th October), Madame du Barry, Danton, Madame Roland and Robespierre.

Place de la Concorde

Following those dreadful events of the Reign of Terror, the Directorate changed the square’s name in 1795 to one of reconciliation and hope: Place de la Concorde.

The Monuments of French cities

In the 1830s, architect Jacques Ignace Hittorff transformed the square by adding statues and fountains that can be seen today.

At each corner of the octagon formed by the Place, he erected eight stone monuments representing the French cities of:

The Monument of Bordeaux © French Moments

The Monument of Bordeaux © French Moments

The fountains

Hittorff also added two monumental fountains inspired by those in Piazza Navona in Rome:

- the Maritime Fountain (to the South, portraying the maritime spirit of France) and,

- the Fountain of the Rivers (to the North, representing the Rhône River and the Rhine River).

Fountain of the Rivers © French Moments

Fountain of the Rivers © French Moments

The Luxor Obelisk, Paris’ oldest monument

Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Place de la Concorde © French Moments

The Obelisk, ideally placed in the middle of the Place de la Concorde, is part of the strange geometrical layouts and alignments along the Historical Axis, evoking the symbols of Ancient Egypt.

Napoleon’s campaign to Egypt

To understand the reasoning that led the French to develop such admiration for Egyptology, let’s go back to Napoleon Bonaparte’s campaign to Egypt in 1798. The French Emperor-to-be attempted to conquer Egypt to counteract the English influence in the Middle East and India. The General was not coming to Egypt with soldiers only. As a newly elected French Academy of Sciences member, he took 167 savants to Egypt in 1798. There he founded the first modern scientific institute in Egypt: the Institut d’Egypte in Cairo.

Obelisk, Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Obelisk, Place de la Concorde © French Moments

The Luxor obelisk on its way to France

King Charles X (1757-1836) showed an interest in Ancient Egypt and commissioned Jean-François Champollion (who deciphered the ancient hieroglyphs) to arrange for an obelisk to be returned to Paris.

In 1831, Mohammed-Ali, Viceroy of Egypt, offered France one of the two obelisks which guarded the entrance of the temple of Luxor in Upper Egypt. Both date back to Pharaoh Ramses II, the most powerful king of Ancient Egypt.

A unique ship, the Luxor, was designed to carry the obelisk to France down the Nile and across the Mediterranean Sea to the port city of Toulon and then by river to Paris.

In Charles X’s plans, the obelisk had to find its place on Place de la Concorde. That is the square built in honour of his grandfather and where his brother and sister-in-law were beheaded.

Raising the Obelisk on place de la Concorde

On the 25th of October 1836, 200,000 people gathered at the square to witness the lifting operation to raise the obelisk onto its pedestal.

Erection of the Luxor Obelisk on Place de la Concorde in 1836. Painting by François Dubois

Erection of the Luxor Obelisk on Place de la Concorde in 1836. Painting by François Dubois

To the relief of supervisor Lebas and the assembled crowd, the event was a success. From that day, the “Obélisque de Louxor” sits enthroned in the centre of the square.

The Obelisk seen from the entrance to the Tuileries Garden © French Moments

The Obelisk seen from the entrance to the Tuileries Garden © French Moments

The oldest monument in Paris

Some 3,500 years old, the obelisk is the oldest monument standing in Paris. It is 23 metres tall and weighs 220 tons. However, the French capital was not the only European city to display an obelisk.

Other Egyptian obelisks in Europe

- The Romans transferred the one standing in Saint Peter’s Square in Rome to decorate the circus.

- Another specimen erected after that of Paris is in London (the obelisk of Tuthmosis III on the Victoria Embankment, better known as Cleopatra’s Needle).

- Without forgetting New York (a twin obelisk to the one in London, erected in Central Park).

The pyramidion

When the obelisk was carried to France in the 19th Century, its original cap had long disappeared. In fact, it was believed to have been stolen in the 6th century BC.

In May 1998, the French authorities decided to refurbish the obelisk by putting a copy of the missing gold-leafed pyramid cap on top, thanks to the initiative of Egyptologist Christiane Desroches Noblecourt. This pyramid cap is called a pyramidion. It is supposed to reflect the rays of the sun.

The obelisk’s pyramidion © French Moments

The obelisk’s pyramidion © French Moments

In 1988, this tremendous Egyptian landmark was joined by another pharaoh-related structure along the Historical Axis: the modern Glass Pyramid in the Louvre, evoking the Great Pyramid of Giza.

A perpendicular perspective on the Historical Axis

The Place de la Concorde set the stage for another North-South perspective, much shorter, perpendicular to the Historical Axis.

It features, on the South side, beyond the bridge “Pont de la Concorde” across the Seine:

In fact, both monuments match each other across the Place de la Concorde with their grand Classical-style porticos, evoking the design of Roman temples.

The great perspective from the Madeleine church towards the Bourbon Palace © French Moments

The great perspective from the Madeleine church towards the Bourbon Palace © French Moments

The 19th-century Madeleine Church strangely resembles a Roman temple and shares some similarities with the ancient ‘Maison Carrée’ in Nîmes.

The Madeleine church seen from the square © French Moments

The Madeleine church seen from the square © French Moments

The Palais Bourbon housed the National Assembly, and its pedimented, collonaded front was inspired by the Madeleine Church at the far end of the short perspective crossing the Place de la Concorde.

Palais Bourbon from the square © French Moments

Palais Bourbon from the square © French Moments

The Pont de la Concorde

Pont de la Concorde, Paris © French Moments

Pont de la Concorde, Paris © French Moments

The Pont de la Concorde, crossing the Seine and linking the Place de la Concorde to the Palais Bourbon, was completed in 1791, with many of its stones taken from the dismantled Bastille fortress. When complete, it was said that the people of Paris could ride roughshod over the ancient fortress.

The view from the bridge stretches to the Eiffel Tower, the Alexandre III Bridge on one side, and the other to the Tuileries Garden and the Louvre.

More photos of Place de la Concorde

The fountain of the seas in Place de la Concorde © French Moments

The fountain of the seas in Place de la Concorde © French Moments The three needles of Paris! © French Moments

The three needles of Paris! © French Moments Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Place de la Concorde © French Moments The Historical Axis of Paris in the Tuileries garden near Place de la Concorde © French Moments

The Historical Axis of Paris in the Tuileries garden near Place de la Concorde © French Moments Winter in Place de la Concorde, Paris © French Moments

Winter in Place de la Concorde, Paris © French Moments Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Until the mid-2010s, a Ferris wheel stood in the centre of the square during the Christmas period. It allowed taking beautiful pictures from the beautiful perspective of the Champs-Elysées.

Christmas in Paris – Place de la Concorde © French Moments

Christmas in Paris – Place de la Concorde © French Moments The view from the Ferris wheel © French Moments

The view from the Ferris wheel © French Moments The square at night © French Moments

The square at night © French Moments The fountain illuminated © French Moments

The fountain illuminated © French Moments Place de la Concorde by night © French Moments

Place de la Concorde by night © French Moments

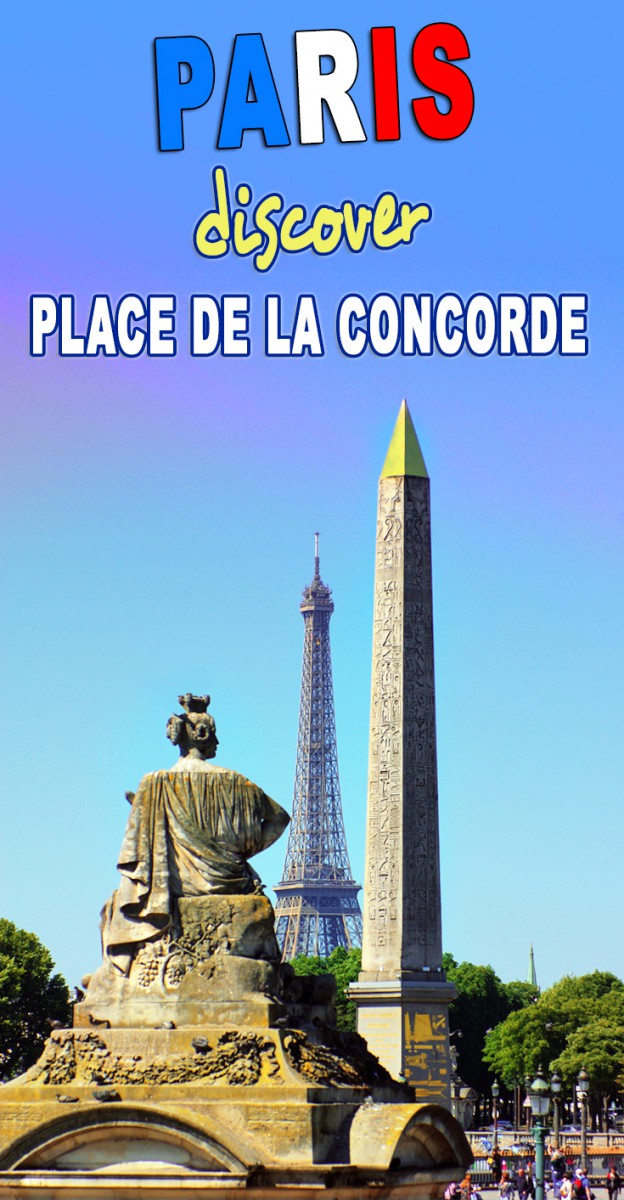

Pin it for later

Did you like what you read? If so, I invite you to leave a comment below. Tell us what the most exciting thing you learnt from the article was!

Also, make sure to pin the image below on Pinterest:

https://frenchmoments.eu/place-de-la-concorde-paris/