|

|

General: THE ANCIENT EGYPTIAN TIME MACHINE LUXOR

Scegli un’altra bacheca |

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 1 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

The Ancient Egyptian Time Machine

The ancient Egyptians believed that the essence of a deity could inhabit an image of that deity, or, in the case of mere mortals, part of that deceased human being’s soul could inhabit a statue inscribed for that particular person.

Edward Bleiberg: Curator of Egyptian, Classical and Near Eastern Art

Blame it on my love of adventure films such as Raiders of the Lost Ark and Curse of the Mummy, but I actually got a bit spooked wandering alone deep inside the tomb of Pharaoh Ramses IV in Egypt’s legendary Valley of the Kings. Should I defy the tourist signs and take a photo of the 3,000 plus-year old sarcophagus, risking my own curse? I snapped a few. The temptation was simply too much to overcome.

The more than 3,000-year old carved stone sarcophagus of New Kingdom Pharaoh Ramses IV located within his burial chamber in the Valley of the Kings just outside present day Luxor, Egypt. Can you feel the vibe? Photo: Henry Lewis.

I recalled reading that Ramses IV had impatiently waited for his father to die in order to create his own historic legacy by building monumental structures that would bear witness to his greatness for millennia after his time. Unfortunately for him, Ramses III – whom scholars call the last great monarch of the New Kingdom – lived a long life, leaving his son only six years to rule before his own death. Perhaps the restless spirit of Ramses IV still inhabited the tomb, forever longing to fulfill his lost promise.

Standing in the crypt’s shadowed stillness, my attention was drawn upward to a row of hieroglyphs near the top of the stone wall. As my eyes carefully examined each detail, my mind drifted off in a sea of daydreams. Physical awareness slowly melted away until I was no longer conscious of my mind’s connection to an earthly body. Until, that is, I suddenly felt something grasp my left shoulder as I let out an audible scream.

I was greeted by a smiling Egyptian man dressed in a threadbare traditional tunic who now stood in the corridor beside me. Unlike ancient tomb-raiders who went to great lengths to access buried treasure, he had merely walked past the guard in his quest for tourist dollars.

My initial reaction was one of annoyance, considering I’d just been unwillingly plucked from an extraordinary out-of-body experience in an ancient Pharaoh’s tomb. However, my emotions were soon calmed by the knowledge that I was extremely fortunate to have the resources to travel to such an amazing place. I let go of my attachment to what I saw as being lost, and instead made the most of chatting with my new friend as we both exited the tomb.

The local Egyptian man who ‘rescued’ me from the crypt of Ramses IV. Photo: Henry Lewis via the tomb’s Guard.

Such are the common occurrences when traveling in a land so steeped in ancient monuments that ghosts both real and imagined seemingly lurk around every corner. Egypt truly is a living time machine, ready to transport even the most jaded traveler to unexpected adventure.

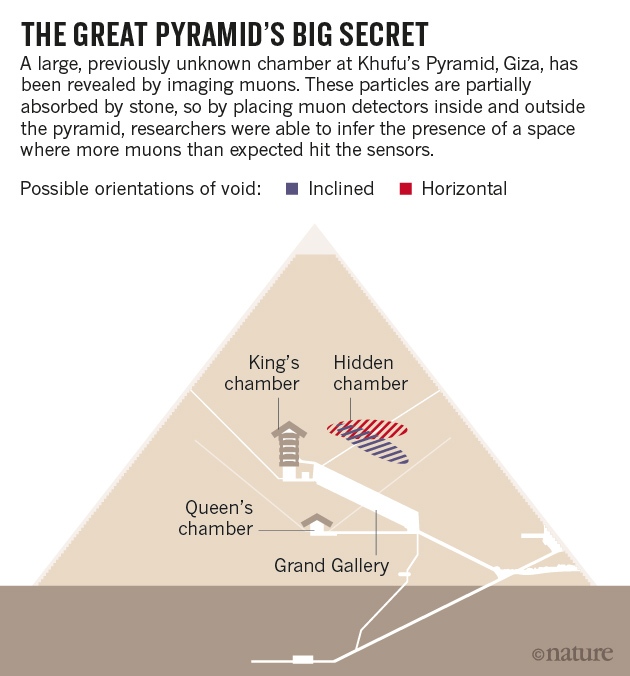

Great Pyramid of Giza

The three pyramids that make up the Giza pyramid complex, located on the edge of the city of Giza in greater Cairo, are the quintessential symbols of ancient Egyptian architectural mastery. However, as impressive as they are, these towering stacks of precisely cut blocks of stone are merely the doorway to a world of ancient architectural treasures. The tallest and oldest of the three, the Great Pyramid of Khufu, is the oldest and most intact of the original Seven Ancient Wonders of the World.

The token tourist photo snapped in front of the 146.5 metres (481 feet) high Great Pyramid of Khufu (also sometimes called the Pyramid of Cheops), the tallest of the three pyramids collectively known as the Great Pyramids of Giza which sit on a broad desert plain just outside Cairo. Should I be embarrassed by this bit of cultural appropriation? At the time it felt harmless and the vendor/photographer sure seemed desperate for some business. I visited the country in 2010 at a time when tourist visits were down significantly due to the perceived threat of terrorism. Photo: Henry Lewis via camel Vendor.

The Great Sphinx of Giza – believed to have been constructed during the reign of Pharaoh Khafre (c. 2558–2532 BC) during the period of the Old Kingdom – stands on the Giza Plain just in front of (but facing away from) the Great Pyramid of Khafre. Scholars believe the mythical creature’s head features a likeness of Khafre. Photo: Henry Lewis.

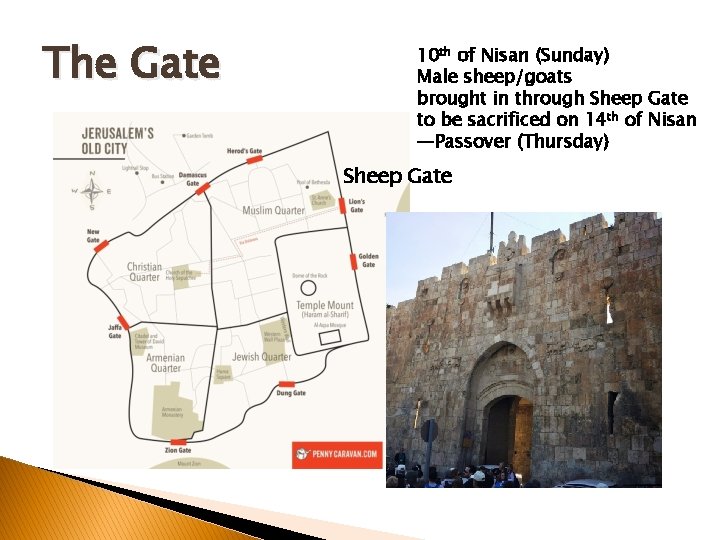

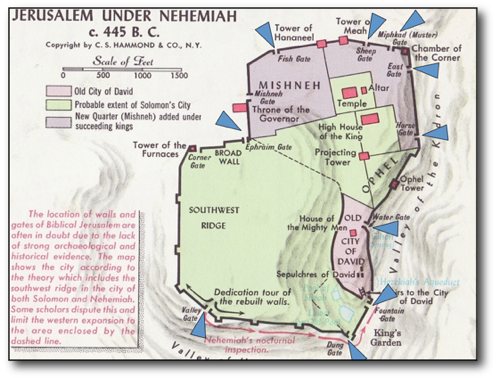

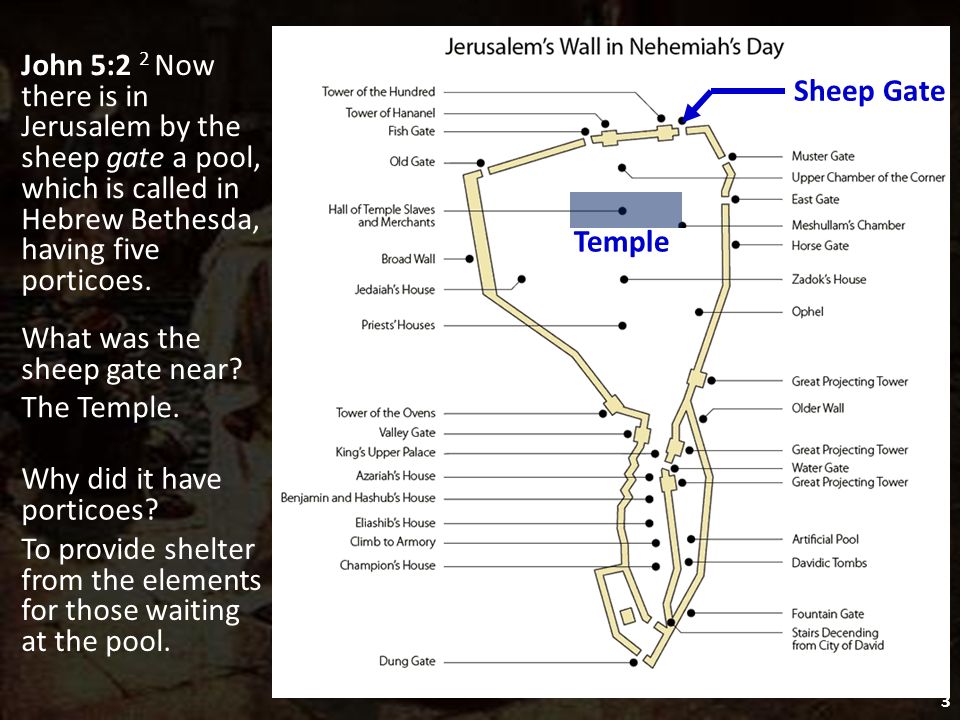

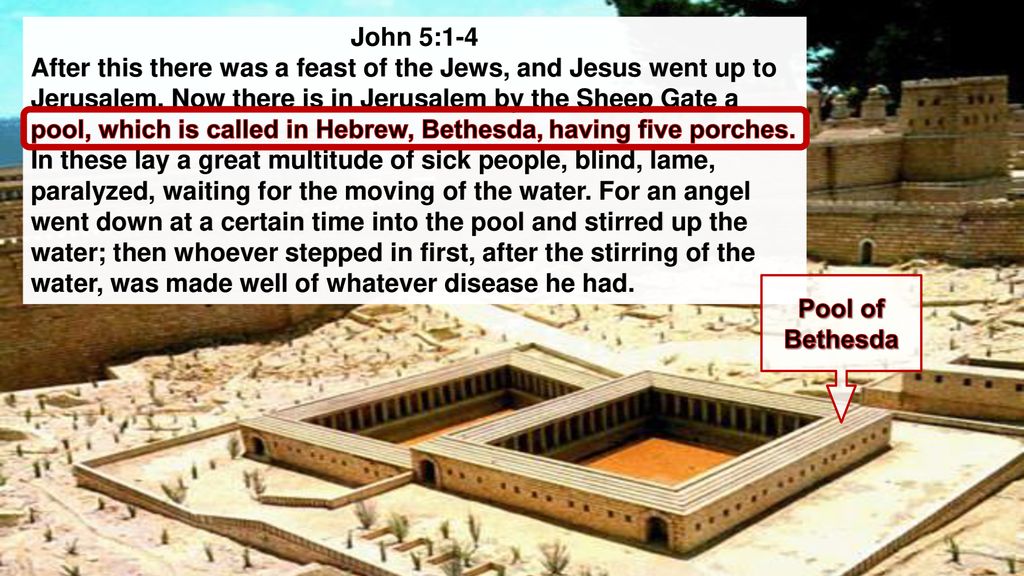

Karnak Temples — Luxor (Ancient Thebes)

The Karnak Temple Complex, located along the Nile in present day Luxor, is approximately an 8-hour drive or 90-minute flight south from Cairo. Ancient Thebes was the capital of Egypt during the period of the New Kingdom (c.1570 – c.1069 BCE) and Karnak was the center for religious activity in the city, particularly owing to its dedication to the ‘King’ of Egyptian gods – Amun-Ra (also known as Amun-Re).

The Karnak Temples are set apart from others in Egypt due to the fact they were constructed over a period of approximately 2,000 years (c. 2,000 BCE – c. 30 BCE) by as many as 30 different Pharaohs. Such a long historical record has produced visible layers, punctuated by stories of palace intrigue as successive rulers tried to elevate their own historical legacy by undoing the carved-stone signatures of those who ruled before them.

Interior of Karnak Temples looking from the court of the Bubastites towards the Great Hypostyle Hall. Photo: Henry Lewis.

The massive stone columns of Karnak’s Great Hypostyle (stone columns covered by a roof) Hall. This section of the temple was intended to invoke a sense of awe just as Europe’s cavernous medieval cathedrals did thousand’s of years later. The hall has 134 immense sandstone columns with the center twelve columns standing at 69 feet. Like most of the temple decoration, the hall would have been brightly painted and some of this paint still exists on the upper portions of the columns and ceiling today. Photo: Henry Lewis via tour guide.

A small hypostyle hall inside Karnak Temples showing signs of the colorful paints that once adored the columns, walls and ceilings. Photo: Henry Lewis.

A falcon with spread wings and other carved inscriptions cover this sandstone wall on the interior of Karnak Temples. Other common hieroglyphic symbols such as the Eye of Horus, scarab (beetle) and ankh are clearly visible. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Note the varying depths of these relief carvings on the interior of Karnak Temples. When a new Pharaoh assumed power, they often instructed the stone masons to carve symbols of their rule ever deeper into the stones, thereby attempting to erase (and usurp) the stories set in stone by previous Pharaohs. Due to Karnak’s long history of construction by as many as 30 different rulers, the temples’ walls record a vast treasure trove of Egyptian history. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Luxor (Ancient Thebes) Temples

Although secondary in religious importance to Karnak Temples, the Luxor Temple Complex (c. 1400 BCE) was nonetheless an important part of daily ritual life in ancient Thebes. Situated on the Nile just two kilometres south of Karnak, religious festivals involved processions that flowed along the Avenue of the Sphinxes which connected the two temple complexes.

Unlike the other temples in Thebes, Luxor temple was not dedicated to a cult god or a deified version of the pharaoh in death, but was instead dedicated to the perpetuation of the line of Pharaohs. It may have been where many of the pharaohs of Egypt were crowned.

The north entrance to the Court of Ramses II at Luxor Temple Complex with the Abu Haggag Mosque seen here in the upper left. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Despite being constructed over a shorter time span than Karnak, there are still many layers of history that can be observed within the Luxor Temples Complex. The part of the Luxor Temple seen in the photo above was converted to a church by the Romans in 395 AD, and then to a mosque in 640. Seen here is the Abu Haggag Mosque which is still in use and was built on the original ancient temple walls as well as on the remnants of a Christian church. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Frescoes from the early Christian era can be seen on these interior walls of Luxor Temple. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Exterior sandstone columns of Luxor Temple as seen at dusk. Photo: Henry Lewis.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut — Luxor (Ancient Thebes)

Hatshepsut was the 2nd historically confirmed female pharaoh and ruled Egypt from 1507–1458 BC. Historians often note that she is the earliest example of a clearly documented female ruler of a major kingdom.

The perfectly symmetrical Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut sits beneath the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari on the west bank of the Nile near the Valley of the Kings. This temple is dedicated to Amun-Ra and Hatshepsut and is carved into the sandstone hillside.

Gazing at the vast complex from the front, I was astonished at the modern lines of the temple itself. Hatshepsut’s mortuary temple wouldn’t look out of place in one of today’s great world cities. This is further testimony to the great skill and extraordinary vision of ancient Egyptian architects.

Approaching the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut which sits under the cliffs of Deir el-Bahri, just outside present day Luxor in Egypt’s Upper Nile valley. Photo: Henry Lewis.

A wall in the interior of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut is adorned with the image of the supreme Egyptian god Amun-Ra, depicted in the usual way with two plumes on his head. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Osirian (from the god Osiris) statues of Queen Hatshepsut once adorned the front of every column on the exterior of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. A few have been recreated to give visitors a feel of what was once quite an impressive display. Photo: Henry Lewis.

Close-up of a recreated stone statue of Pharaoh Hatshepsut holding the ‘crook and flail’, symbols of the pharaoh’s power borrowed from the Egyptian god Osiris. Photo: Henry Lewis.

peace~henry

https://myquest.blog/2020/06/27/the-ancient-egyptian-time-machine/ |

|

|

Primo

Primo

Precedente

2 a 14 di 14

Successivo

Precedente

2 a 14 di 14

Successivo

Ultimo

Ultimo

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 2 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 3 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

EL CERN, NI CIENCIA NI MAGIA: ALQUIMIA

Hace años que vengo siguiendo las actividades Illuminati en diferentes ámbitos (social, cultural, científico, educativo, político, etc.), y siempre hay algunos puntos que permanecen "oscuros" por un cierto tiempo, hasta que finalmente desvelamos su real significado e intencionalidad. El Gran Colisionador de Hadrones, GCH (en inglés Large Hadron Collider, LHC) del CERN, junto con el Acelerador Relativista de Iones Pesados o RHIC por sus siglas en inglés (Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider), han sido algunos de los "avances" científicos que hemos tenido entre ojos, vigilando su desarrollo para descubrir cuál es el objetivo que se esconde por detrás de ellos, detrás de la "inocente" propuesta de "recrear el segundo previo al Big Bang".

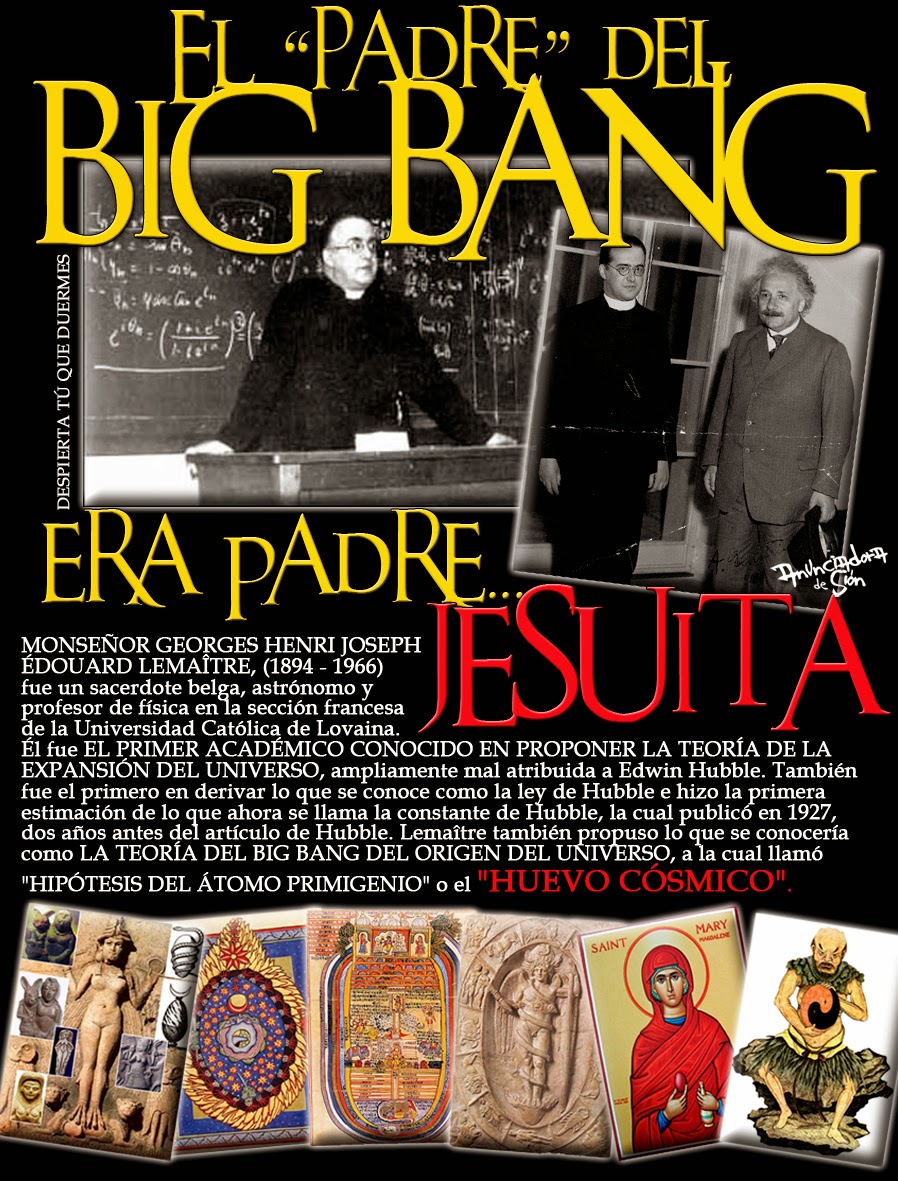

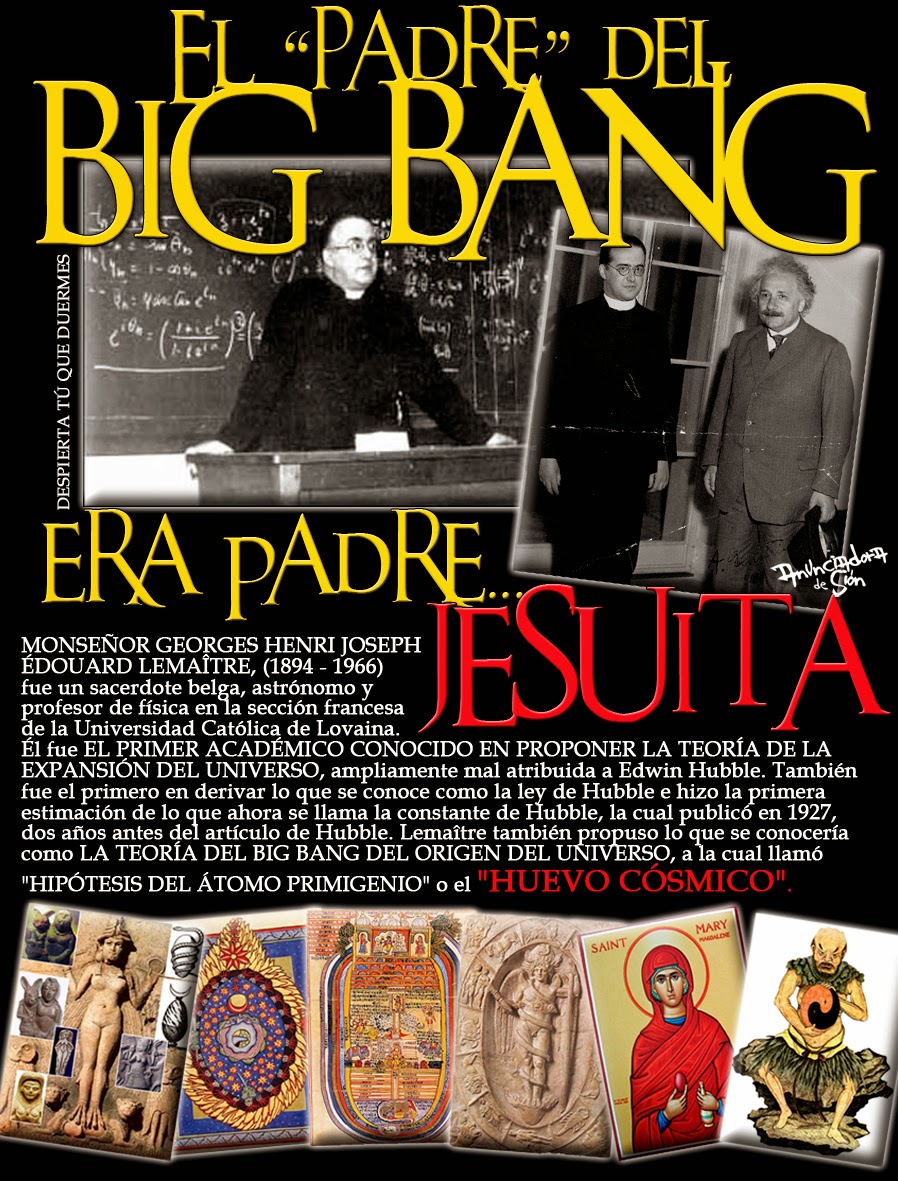

Por cierto, la teoría del Big Bang fue elaborada por un jesuita... ¿sabían? Este no fue Papa pero seguro lo canonizan...

Monseñor Georges Henri Joseph Édouard Lemaître, (1894 - 1966) fue un sacerdote belga, astrónomo y profesor de física en la sección francesa de la Universidad Católica de Lovaina. Él fue el primer académico conocido en proponer la teoría de la expansión del universo, ampliamente mal atribuida a Edwin Hubble. También fue el primero en derivar lo que se conoce como la ley de Hubble e hizo la primera estimación de lo que ahora se llama la constante de Hubble, la cual publicó en 1927, dos años antes del artículo de Hubble. Lemaître también propuso lo que se conocería como la teoría del Big Bang del origen del universo, a la cual llamó "hipótesis del átomo primigenio" o el "huevo cósmico". (Demasiado "mitológico" para mi gusto...). Un huevo cósmico o huevo del mundo es un tema mitológico y cosmogónico usado en los mitos de creación de muchas culturas y civilizaciones. Típicamente el huevo cósmico representa simbólicamente un comienzo de algún tipo.

Irónicamente la teoría del Big Bang se atribuye generalmente a Albert Einstein, quien fue el principal detractor de Leimatre hasta que, años después, comprobó que el religioso belga había acertado en los cálculos astronómicos, de alta complejidad, y juntos profundizaron las investigaciones. (De hecho, el "genial" Alberto anduvo robando por todas partes... también a Tesla).

Volviendo al tema central del CERN, he llegado a la conclusión, después de tomar en cuenta toda la información y las personas asociadas con el proyecto, que no es OTRA COSA SINO UNA APLICACIÓN MÁS DE LOS ILLUMINATI DE UNA ANTIGUA TECNOLOGÍA OCULTA DE LOS ÁNGELES CAÍDOS. Los Illuminati están obsesionados con el cumplimiento de lo que George Bush (padre) llamó el "cumplimiento de un antiguo sueño", en referencia a la vuelta a los días anteriores a Noé, cuando los híbridos gigantes habitaban en la tierra. El restablecimiento del estado de la Atlántida de los reyes filósofos.

Con todo, una de las cosas que más llamó la atención cuando la creación del CERN, y que la mayoría de la gente no conseguía entender, fue CUÁL PODÍA SER LA RELACIÓN ENTRE UN COLISIONADOR DE HADRONES "TECNOLÓGICO Y CIENTÍFICO" Y UNA ESTATUA DEL DIOS SHIVA, "EL DESTRUCTOR", COMPLETAMENTE MÍSTICO Y MITOLÓGICO.

.jpg) |

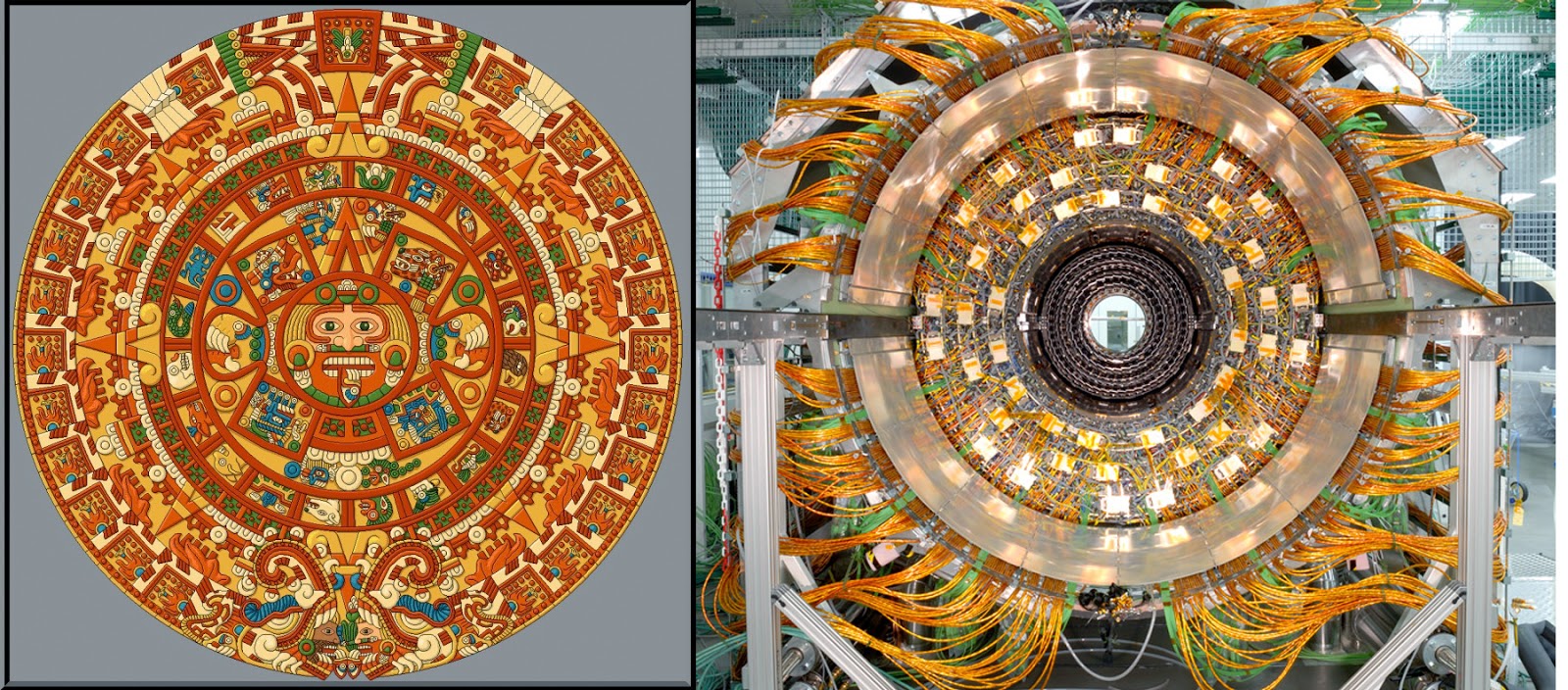

| Observen el círculo que rodea al dios Shiva en su danza, y compárenlo con el acelerador de partículas. |

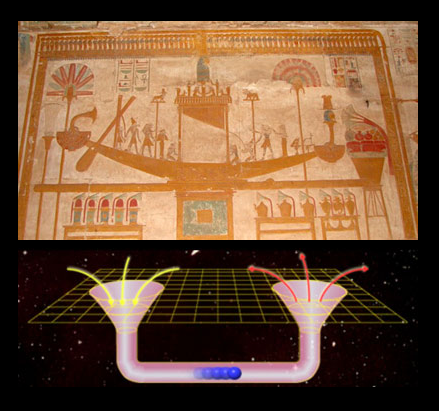

Ahora bien, lo interesante de todo esto es que algunos han relacionado todos estos elementos con lo que se conoce popularmente como Stargate, o portales ("VORTEX-GATE... PROCURANDO LA PUERTA DE SALIDA"). Hay varias teorías acerca de si el CERN es o no un Stargate. Pero vemos un poco acerca de lo que es conocido por los amantes de lo paranormal como "el dispositivo de Osiris", el Ta-Wer. Según los estudiosos, el Ta-Wer era un solo un símbolo místico que representaba la conexión entre Abydos (ciudad egipcia) y un lugar mítico en el mundo subterráneo, interpretado como la "Tierra de los muertos".

Bueno, es un sentimiento común entre los investigadores de ovnis que el Ta-Wer representado en algunas imágenes, en las paredes del templo de Abydos, es una estructura que podría ser parte de un gran dispositivo que activa portales dimensionales, puertas estelares o agujeros de gusano.

Arriba pueden ver un modelo de agujero de gusano cósmico en comparación con el "dispositivo de Osiris", que coincide con la teoría de Kurt Gödel, que por el hecho de que nada puede viajar más rápido que la luz, un "atajo" podría ser abierto en ciertas coordenadas del espacio, para conectar dos puntos distantes. Una enorme cantidad de energía que produciría una enorme cantidad de gravitación que podría "doblar" el espacio, formando dos conos de luz interconectados por un túnel espacio-tiempo donde podría pasar la materia.

La historia oficial: El LHC es un acelerador de partículas, construido para emitir protones a muy alta velocidad y en direcciones opuestas, para que choquen entre sí, creando una enorme cantidad de energía capaz de reproducir las condiciones cósmicas similares a aquellas que generan fenómenos tales como la materia oscura, la antimateria y en última instancia, la creación del universo hace miles de millones de años. El equipo científico mantiene la velocidad de rayo hacia arriba, entre el 3,5 y 12 TeV (Teraelectron voltios) para llegar a una energía de colisión alrededor de 90 veces a más de 500 TeV.

La historia "oculta": De acuerdo con la Prof. Irina Aref'eva y el Dr. Igor Volovich, ambos físicos matemáticos en el Instituto de Matemáticas Steklov en Moscú, las energías generadas por las colisiones subatómicas en el LHC pueden ser lo suficientemente potentes como para rasgar el espacio-tiempo, generando agujeros de gusano. Lo mismo opinan otros físicos (ver aquí).

Es una idea común al 99% de los físicos "fuera del sistema CERN", que el LHC puede producir suficiente energía como para abrir agujeros de gusano, lo que lo convierte en un dispositivo STARGATE enorme. Lo que quiero decir es que la "búsqueda de la partícula de Dios" es una bandera falsa, una tapadera para ocultar OTRA COSA... para variar.

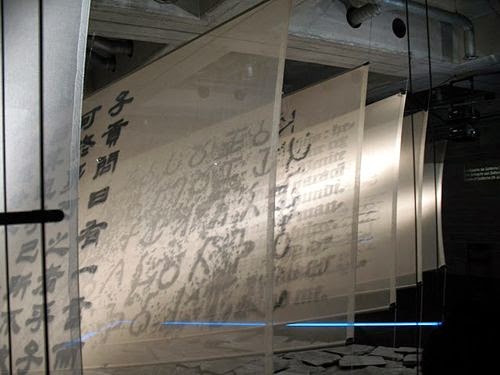

Además de todas estas cosas, como cereza del postre, nos encontramos con los siguientes paneles dentro de las instalaciones del LHC:

Esto es MUY raro... las fotos que ven arriba fueron tomadas DENTRO de la instalación LHC. Se trata de extraños paneles con escritas antiguas, montados sobre una estructura y con algún tipo de haz de luz azul que los rodea, algo que parece ser un sensor de movimiento o cosa parecida. Algunos paneles parecen escritos en mandarín antiguo, otros tienen caracteres árabes, otro en hebreo, otro en sánscrito y otro contiene unos caracteres muy extraños, que no se parecen con nada que haya visto antes. En la India, las únicas personas que leen y escriben en sánscrito, son los estudiosos de los Vedas y los Upanishads, las escrituras escritas en el "lenguaje de los dioses". ¿Por qué estos paneles tienen sensores de seguridad, por qué están en el CERN, y para qué sirven?

Bien, pero las referencias místico-mitológicas no terminan con el antiguo Egipto. Ya conocemos la historia de Nimrod, que construyó una torre que fue diseñada para ser una escalera o puerta de entrada al cielo, la famosaTorre de Babel. Según la mitología tradicional, Nimrod quería conocer a Dios y entender su funcionamiento. Su torre era, literalmente, una escalera a las estrellas, una manera de entrar en la dimensión en la que Dios habitaba.

Hay ocultistas y mitólogos como William Henry que han afirmado que los antiguos como Nimrod y otros utilizaron estas torres y puertas estelares. Las torres crean agujeros de gusano y los dioses de las estrellas pasarían a través de ellas. Pero, por supuesto, a Dios no le gustó la idea y confundió el idioma de la gente de Nimrod. En contrapartida, Nimrod ORGANIZA LA MASONERÍA. Ellos continuaron construyendo estos portales estelares y templos.

A lo largo de la historia antigua ha habido muchos relatos de dioses que viajaban de un lugar a otro utilizando intrincadas maquinarias que los llevarían de una dimensión a otra. Hay historias de la antigua Sumeria que hablan acerca de los llamados "dioses", llegando a través de una puerta estelar doble con columnas, y existen tallas que han representado tal hazaña.

Ha habido muchos intentos de abrir agujeros de gusano y, al mismo tiempo, el objetivo de estos trabajos mágicos era convocar alguna manera demonios o ángeles para venir e iniciar la escatología (los tiempos finales). Hay un montón de magos que han afirmado que han abierto un agujero de gusano usando métodos mágicos. Estos son los métodos que se dice han traído a otros seres a nuestra existencia dimensional.

Todos hemos oído hablar que en algún lugar existe algún grupo secreto que controla el mundo. Sin embargo, es necesario entender que hay varios grupos con agendas programadas, y que no son en absoluto en contra del uso de la magia oscura para lograr sus fines desconocidos. Algunos teóricos esotéricos creen que las fuerzas mágicas trabajan para dar forma a nuestras vidas. Y que la élite tiene entre sus filas al más oscuro de los magos o a los profesionales de las artes oscuras que pueden llegan a la matriz y cambiar las líneas de tiempo mediante la apertura de portales o "puertas estelares" a otros mundos.

La idea de dar un empujón dimensional para abrir una puerta e invitar a un dios o una entidad a entrar, ha sido el desafío desde la época de Nimrod hasta los tiempos de John Dee, Edward Kelly, Aleister Crowley, L. Ron Hubbard y hasta Jack Parsons.

Entre los años 1582 y 1589 el erudito Inglés John Dee llevó a cabo una serie de comunicaciones rituales con un conjunto de entidades desencarnadas que con el tiempo llegó a ser conocido como los ángeles de Enoc. El plan de Dee era utilizar el complejo sistema de magia comunicada por los ángeles para avanzar en las políticas expansionistas de su soberano, la reina Isabel I. ¿Para qué? ¿Simplemente para expandir las tierras? NO. Ya estaban sentando las bases que eran necesaria para desarrollar todo el plan del NUEVO ORDEN MUNDIAL. En primer lugar y lo más importante de todo, conquistar las tierras estratégicamente repartidas alrededor del mundo que hoy les permiten tener una COBERTURA TOTAL DEL GLOBO. Todo esto, evidentemente, no por sabiduría de hombres. Este plan NO ES SIMPLEMENTE HUMANO.

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 4 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

Con la ayuda de su compañero, el investigador ocultista Edward Kelley, planeaban abrir un portal al otro lado con las claves inferiores de Enoc, un alfabeto mágico que fue cantada. Literalmente estaban convocando a los espíritus de los muertos para hacer espionaje para la reina, y de acuerdo con la historia tuvieron bastante éxito. Estas entidades declararon que el nombre celestial para Satanás era Choronzon y que había al menos 4 torres de vigilancia o pilares en los que existen puertas estelares en la tierra. También hay una manera de abrir portales en otro lugar, siempre y cuando ciertas claves y sigilos se utilicen para convocar a las entidades a fin de llevar a cabo un trabajo apocalíptico o hechizo.

Uno de los otros rituales realizados por John Dee fue convocar al Arconte encargado de la puerta, Cernunnos. Para los celtas, Cernunnos, Cerne o Belatucadros, era representado como una figura humanoide, generalmente teniendo cuernos. Uno de los títulos Cernunnos era el señor de la caza, pero a medida que pasaba el tiempo la agricultura se fue uniendo junto con la caza y el Dios Cornudo se convirtió en el dios de la fertilidad también. El culto de esta deidad era realizado esperando alcanzar no sólo buena cacería, sino también garantizar una cosecha abundante e incluso la procreación exitosa de la humanidad. Como tal, lo encontramos representando el concepto de la vida, la muerte y el renacimiento, aunque en otros mitos Cernunnos es representado como un dios con cuernos que controla las serpientes. Las serpientes eran símbolos de la mortalidad, la curación y la resurrección de los muertos, o el uso de los muertos para la adivinación o la nigromancia. Al considerar la muerte como parte integral del "círculo continuo" de la vida, Cernunnos también ha sido asociado a los infiernos, el reino de los muertos.

Las invocaciones y la citación de los arcontes eran parte de algo que se llama "El Trabajo del Apocalipsis". La idea era convocar a varios ángeles y demonios de los bajos fondos para abrir una Puerta Estelar o escalera al cielo.

En realidad, fue uno de los primeros intentos de abrir un portal a otra dimensión y convocar a los espíritus. Fue literalmente un ritual para abrir los secretos del universo y conversar con los dioses. Pero los ángeles nunca permitieron que Dee fuera el instrumento mediante el cual se llevase a cabo la fórmula ritual para iniciar el Apocalipsis. Los ángeles declararon que el "trabajo" tendría que ser realizado en un momento posterior. El ritual sin terminar se sentaría como una bomba de tiempo oculta tictac, esperando que algún mago inteligente, tal vez guiado por los ángeles, para completarlo. Dee nunca recibió la señal para llevar a cabo el Trabajo del Apocalipsis en su vida. Esto estaba reservado para otro siglo y otro hombre. Ese hombre era Aleister Crowley.

Crowley y sus seguidores querían marcar el comienzo de una moral más grave que cualquier otra experiencia en el mundo. Para lograr esto tuvieron que llevar a cabo rituales poderosos. Sus métodos fueron tan aberrantes que Mussolini lo echó de Sicilia llamándolo un "bárbaro". Crowley profetizó que después de su muerte se realizaría un trabajo final o ritual donde se abriría un portal y los "jefes secretos" o antiguos dioses egipcios volverían.

Dos seguidores de Crowley, L. Ron Hubbard y Jack Parsons, intentaron abrir un portal usando uno de los hechizos de Crowley entre 1945 -1946. Fue una serie de ceremonias mágicas llamadas "Trabajo Babilonia" (Babalon Working). Muchas personas creen que lo que atravesó el portal fueron los seres que serían conocidos como los extranjeros "grises".

L. Ronald Hubbard llegó a crear la Cienciología, una religión que enseña que las entidades extraterrestres son responsables del uso de los seres humanos como avatares y que los espíritus extraterrestres fuerzan a la humanidad a hacer el mal.

Jack Parsons se convirtió en el fundador de JPL (Jet Propulsion Lab), y afirmó que durante el "Trabajo Babilonia", tanto él como Hubbard fueron los que lograron la ampliación del portal de Amalantrah de Crowley, permitiendo la entrada a los jefes secretos para "ayudar" a la humanidad. Más tarde intentó otro proyecto secreto, conjurando la clave inferior de Salomón para marcar el comienzo de la gran tribulación. Durante el ritual, él accidentalmente explotó su laboratorio mientras jugaba con poderosos explosivos. Algunos creyeron que él estaba tratando de abrir un Stargate para convocar a los demonios del Goetia.

Los Experimentos del CERN

El CERN está vinculado a varios proyectos secretos que están llevando a cabo la Unión Europea y la Comisión Europea Trilateral. También es el responsable por la existencia de la red de internet (todavía no consigo descubrir cuál es la utilidad de la misma, por lo menos a nivel "portales"; a nivel vigilancia su funcionalidad es OBVIA), y han estado haciendo investigaciones en curso para los gobiernos con respecto a la sostenibilidad global.

También se informó de que en 1999 el CERN propuso y llevó a cabo experimentos cuánticos Vortex en busca de axiones solares. Los axiones son partículas hipotéticas que son componentes de la materia oscura. Con el fin de encontrar estos axiones, el CERN propuso el uso de un imán desarmado llamado Satanás. El nombre era un acrónimo de Solar Axion antena telescópica.

Existen muchos otros experimentos que están relacionados con extraños acontecimientos en diferentes locales, pero sinceramente no tenía ahora el tiempo de verificarlos a todos, de manera que les dejo el dato para los que quieran pesquisar por su cuenta. El hecho más famoso relacionado con uno de estos supuestos experimentos fue la conocida "espiral de Noruega", que apareció en el cielo el 8 de diciembre de 2009... casualmente al mismo tiempo que el colisionador realizaba una prueba. De hecho, más tarde hubo confirmación oficial de que el fenómeno tenía relación con el CERN, y también con el HAARP (no sé cuál).

El famoso 21 de diciembre de 2012

El experimento definitivo en el que finalmente se "descubrió" el bosón de Higgs tuvo lugar entre el 17 y el 21 de diciembre de 2012. ¿Se trató de una mera coincidencia, de una provocación de la comunidad científica o realmente el experimento del CERN tenía relación con el cambio de ciclo Maya? ¿O hay algo más real y oculto? En el centro de nuestra galaxia, la Vía Láctea es un agujero negro super denso.

¿Podrían los experimentos llevados a cabo por el CERN-LHC, el 21 de diciembre de 2012, haber sido una tentativa de liberar a los seres espirituales caídos encerrados en este pozo sin fondo, este Blackhole?

Esta fecha podría haber sido el momento más oportuno para abrir una puerta de entrada o agujero interdimensional en este agujero negro en el centro de nuestra galaxia.

Imagine a la Vía Láctea como una gran cerradura de caja fuerte.

Para abrirla, todas las combinaciones deben estar en el orden correcto, es decir, perfectamente alineadas.

Esta alineación se logró el día 21 de diciembre de 2012, cuando el sistema solar se alineó con el plano galáctico.

La llave (CERN-LHC) podría en aquel momento haber sido insertada (encendida) para abrir la puerta (agujero de gusano a través de la tierra hasta el agujero negro en el centro de la Galaxia).

También a los mensajeros que no guardaron su primer estado sino que abandonaron su propia morada, los ha reservado bajo tinieblas en prisiones eternas para el juicio del gran día. Judas 1:6

El quinto mensajero tocó la trompeta. Y vi que una estrella había caído del cielo a la tierra, y se le dio la llave del pozo del abismo. Y abrió el pozo del abismo, y subió humo del pozo como el humo de un gran horno; y se oscureció el sol y también el aire por el humo del pozo. Y del humo salieron langostas sobre la tierra, y se les dio poder como el poder que tienen los escorpiones de la tierra... Y tienen sobre sí un rey, el mensajero del abismo, cuyo nombre en hebreo es Abadón, y en griego tiene por nombre Apolión DESTRUCTOR.Apocalipsis 9:1-3,11

Porque si Yahweh no dejó sin castigo a los mensajeros que pecaron, sino que, habiéndolos arrojado al Tártaro en prisiones de oscuridad, los entregó a ser reservados para el juicio... 2 Pedro 2:4

Y a Miguel le dijo el Señor: ve y anuncia a Shemihaza y a todos sus cómplices que se unieron con mujeres y se contaminaron con ellas en su impureza, ¡que sus hijos perecerán y ellos verán la destrucción de sus queridos! Encadénalos durante setenta generaciones en los valles de la tierra hasta el gran día de su juicio.

Enoc, capítulo 10

¿Será que el 21 de diciembre de 2012 estos satanistas intentaron (y seguramente con éxito, PORQUE ESTÁ ESCRITO), liberar al REY DE LOS ÁNGELES CAÍDOS, ABADÓN/APOLIÓN, "EL DESTRUCTOR" (SHIVA) DE SU PRISIÓN EN OTRA DIMENSIÓN?

Y aún falta que liberen a los (200) titanes/ángeles caídos que bajaron a la tierra y cohabitaron con mujeres, aquellos Vigilantes de Judas 1:6 y 2 Pedro 2:4, que engendraron una raza de gigantes, los NEPHILINS, que fueron encadenados en LOS VALLES DE LA TIERRA (¿en el interior de la tierra?). El Libro de Enoc dice que estos 200 ángeles caídos (los titanes) están encarcelados en el Tártaro durante 70 generaciones. Una generación en la Biblia es de unos 70-80 años ("El lapso de nuestra vida es de setenta años, y quizás los más robustos lleguen a ochenta", Salmo 90.10). Estos titanes han estado encarcelados por alrededor de 5000-5600 años.

Las profecías mayas y aztecas para el 21 de diciembre de 2012 NO HABLARON NUNCA ACERCA DE UN FINAL APOCALÍPTICO DEL MUNDO. Más bien mencionaban el regreso de "los Nueve", Bolon Yokte Ku. Estos Nueve eran vistos como viviendo en el Inframundo, y se describen generalmente como dioses de los conflictos y de la guerra, y por lo tanto, vinculados con los peligrosos tiempos de transición, malestar social, eclipses, y los desastres naturales como terremotos. Se dice que al final de un baktun, ellos abandonarían su reino subterráneo y surgirían a la superficie de la Tierra, donde batallarían con las 13 deidades de los cielos.

Pero "Nueve Dioses" no son sólo un ingrediente de la cultura maya. Hubo también nueve dioses en la religión del antiguo Egipto, así como en muchas otras (por ejemplo, la India). Para los egipcios, eran también conocidos como los Nueve Principios y estaban vinculados directamente con su Deidad Creadora, Atum. El control de estos Nueve Principios era considerada fundamental para el exitoso gobierno de un faraón: Un control adecuado sobre ellos significaba que el equilibrio (vinculado con la deidad Ma'at) era mantenido y que todo estaba bien con Egipto, el mundo y el universo.

Por tanto, podemos ver que Los Nueve, en un entorno egipcio o maya, estaban estrechamente relacionados, en ambos casos, y determinaban el gobierno de una era, por lo que su consulta es de suma importancia para el éxito de la nación... o del establecimiento de un Nuevo Orden Mundial.

https://despierta-tu-que-duermes.blogspot.com.ar/2015/03/el-cern-ni-ciencia-ni-magia-alquimia.html

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 5 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 6 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 7 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 8 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 9 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

She is interchangeable with Columbia - the feminine personification of the United States. It was in the South Carolina state capital Columbia that Gov. Sanford revealed his Argentine affair... echoed by a train collision in the District of Columbia (Washington DC) on June 22:

June 22 DC Metro subway trains collide - 9 dead, 80 injured

Timeline:

June 18-24: Gov. Sanford missing/crying in Argentina

June 21: 'Impact' Part 1 on ABC; Prince William birthday

June 22: DC Metro Red Line trains in collision

June 23: US Moon probes (LRO/LCROSS) reach Moon

June 24: Gov. Sanford reveals Argentine affair

June 25: Death of Michael Jackson & Farahh Fawcett

'Metro' means 'meter' in Spanish, Italian, Portuguese, etc. The meter is historically defined as 1/10,000,000 of the distance between the North Pole and the equator through Paris, or in other words the Paris Meridian between the North Pole and the equator. The Paris Meridian is also the 'Rose Line' (an esoteric concept popularized by The Da Vinci Code) i.e. a 'Red Line'...

DC Metro Red Line = French/Columbian Rose Line

...traditionally implying the Blood Royal/Sangraal or the Marian/Columbian Bloodline of the Holy Grail.

In Bloodline of the Holy Grail Laurence Gardner writes of the House of Stuart, the royal bloodline to which Princess Diana and her children belong (pp. 344-5):

https://www.goroadachi.com/etemenanki/moonwalker.htm |

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 10 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 11 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

MANDEL NGAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES MANDEL NGAN/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

President Barack Obama welcomes Pope Francis to the White House on September 23, 2015 in Washington, D.C.

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 12 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 13 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 14 di 14 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

Primo

Primo

Precedente

2 a 14 de 14

Successivo

Precedente

2 a 14 de 14

Successivo

Ultimo

Ultimo

|

|

| |

|

|

©2026 - Gabitos - Tutti i diritti riservati | |

|

|

.jpg)