|

|

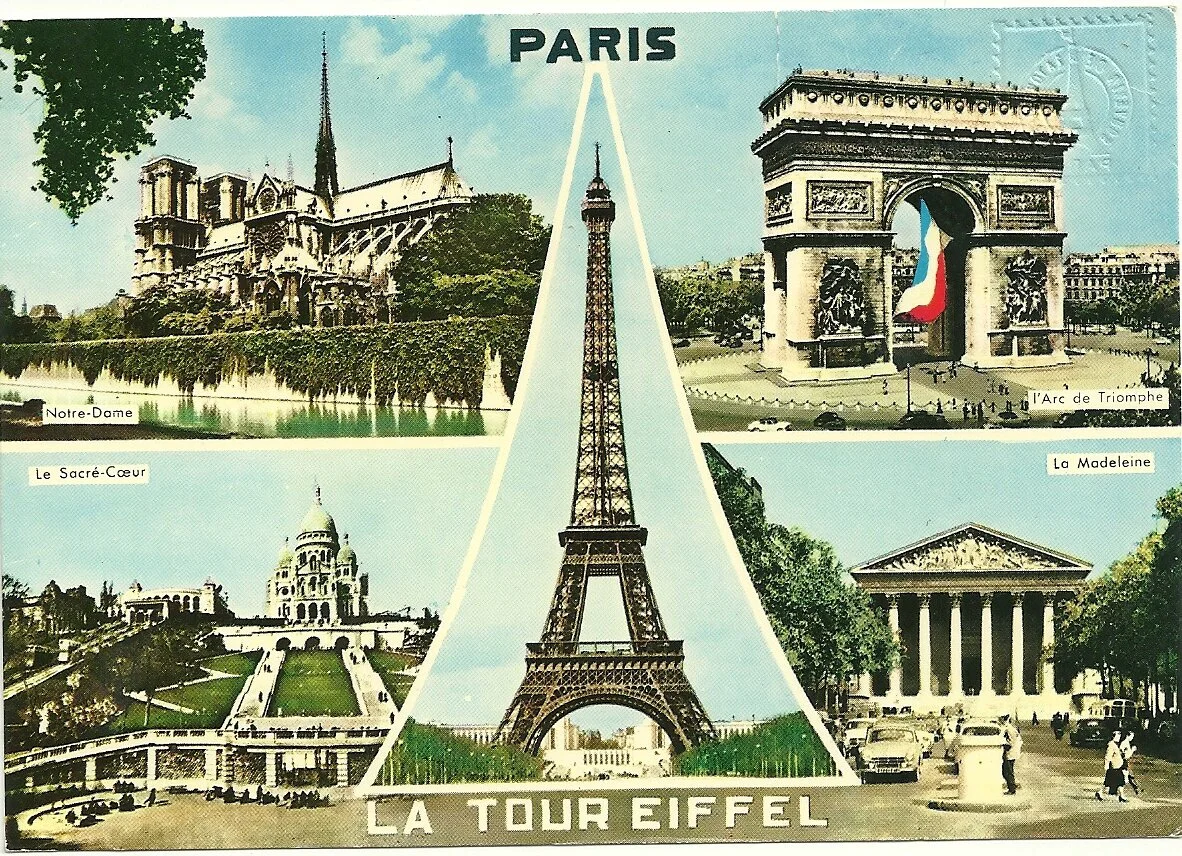

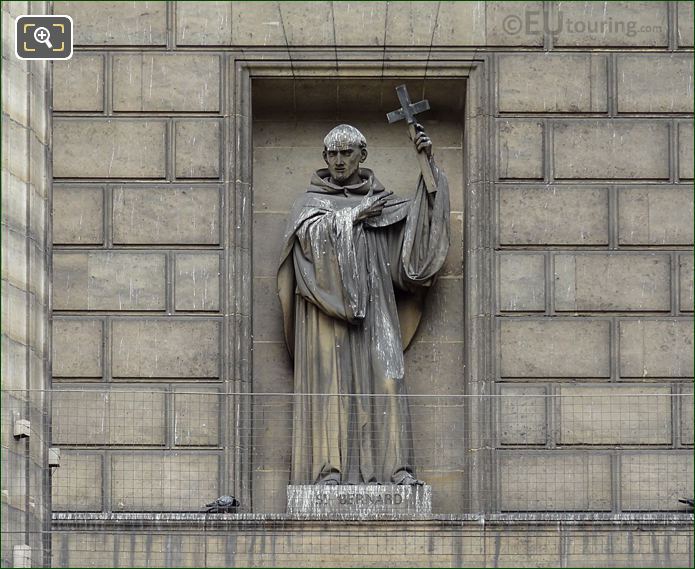

General: SAINT BERNARD CLAIRVAUX STATUE ON EGLISE DE LA MADELEINE IN PARIS

Choisir un autre rubrique de messages |

|

Réponse |

Message 1 de 24 de ce thème |

|

HD photographs of Saint Bernard statue on Eglise de la Madeleine in Paris - Page 1029

We were in the 8th Arrondissement of Paris at the Eglise de la Madeleine, when we took these high definition photos showing a statue depicting Saint Bernard, which was sculpted by Honore Husson.

Paris Statues

- << Previous 1021 1022 1023 1024 1025 1026 1027 1028 1029 1030 Next >>

This first HD photo shows one of thirty-four different saints that are located on the facades of the Madeleine Church, with this one depicting Saint Bernard, which was instigated by the architect Jacques Marie Huve and commissioned by the French state, it was produced in stone back in 1837 while the edifice was still under construction.

Yet here you can see a close up photograph showing some of the detailing that went into producing this Saint Bernard statue, which was by Honore Jean Aristide Husson who was born in Paris in 1803 and entered the Ecole des Beaux Arts under David d'Angers to become a French sculptor, winning the Prix de Rome in 1830.

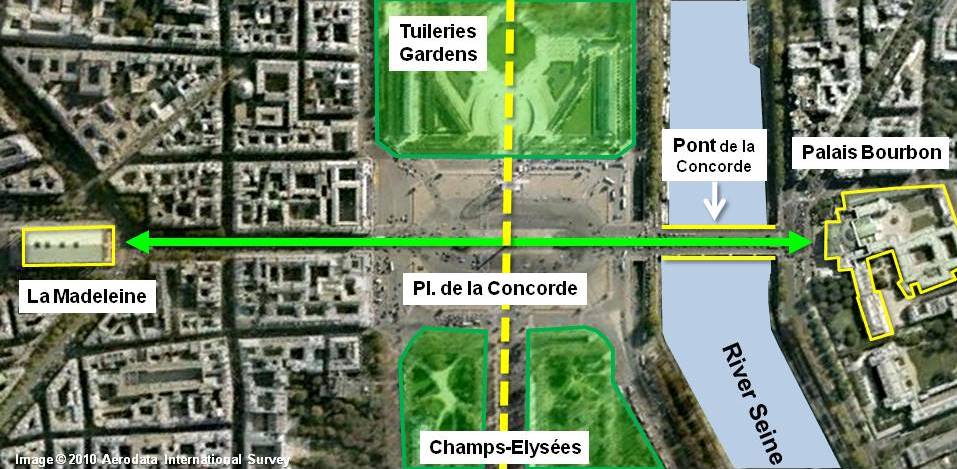

Honore Jean Aristide Husson, often just known as Honore Husson, received many different public commissions for statues, three of which are part of the series of famous men depicted on the facades of The Louvre, but he also worked on decorations for different tourist attractions like one of the fountains at the Place de la Concorde and several for different churches including the Eglise de la Madeleine.

Now Saint Bernard was born to a noble family and studied literature in order that he could study the bible, and becoming a monk, he is also known as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, due to the fact that he founded a monastery he named Claire Vallee, or Clairvaux, he was pronounced an Abbot by the bishop who was head of theology at the Notre Dame de Paris.

The theology and Mariology of Bernard have continued to be of major importance throughout the centuries and he was the first Cistercian monk to be placed on the Roman calendar of saints when canonized by Pope Alexander III on 18th January 1174, and 800 years after his death Saint Bernard was also given the title of Doctor of the Church by Pope Pius VIII, with his feast day being 20th August, the day Saint Bernard passed away in 1153.

So this image shows the location of the Saint Bernard statue within a niche on the eastern portico facade of the Eglise de la Madeleine, and this can be seen through the well recognisable Corinthian columns from the square named after this famous church, where even the funeral of Chopin took place.

https://www.eutouring.com/images_paris_statues_1029.html |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 10 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 11 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 12 de 24 de ce thème |

|

The Nard of Mary-Magdalene

My fools for senses,

Today, we shall be looking for an answer centuries of commentors failed to provide. Following our Review of Irrévérent and its unusual accord of oud and lavender, we decided to ponder awhile on this last ingredient which we thought we knew too well. Most of all, we wanted to envision it with a new eye : that of theology. Of history and literature and cooking and anthropology.

For indeed lavender passed through many cultures and through many readings did we stumble upon a most startling fact : that nard and lavender, in the Bible, are one. Thus, my fools for senses, let us discover today what really hid behind the Nard of Mary-Magdalene.

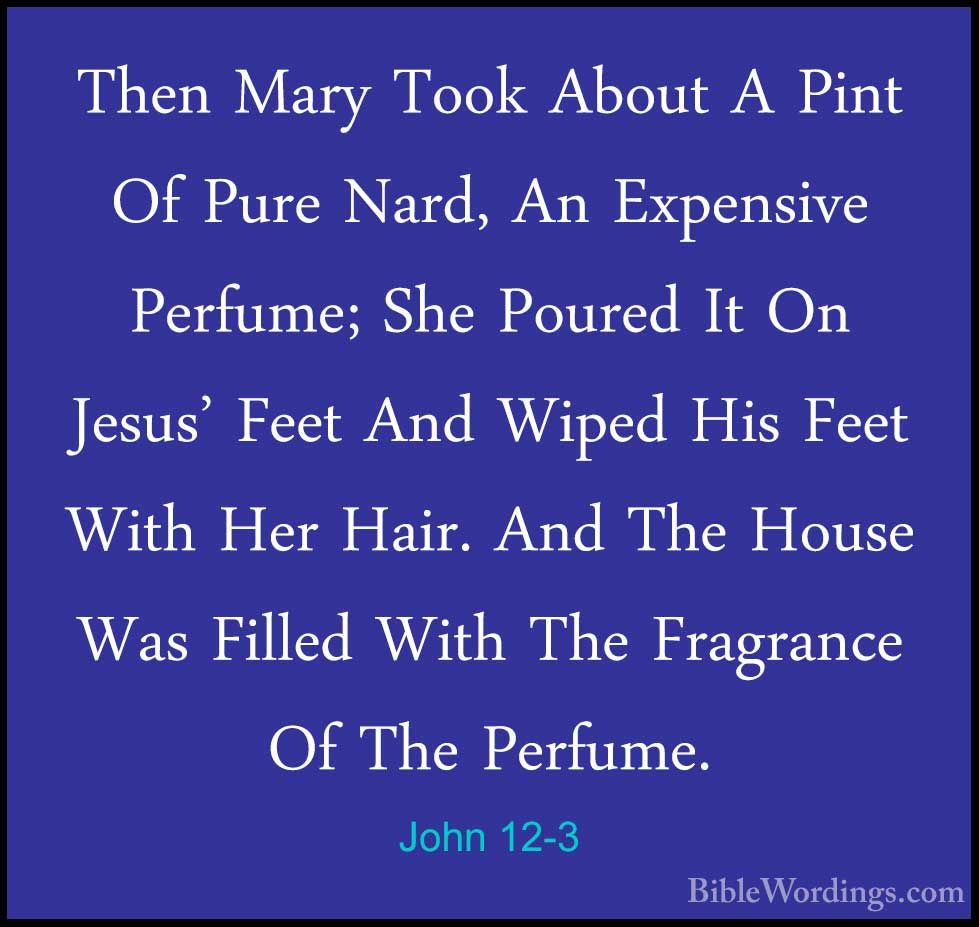

All good adventure movies start with a writing on a wall or in a book in our case. In the Bible, really. “Mary, having taken an ounce of pure nard anointed with it the feet of Jesus” This moving scene will very lively raise more than one question in the reader's mind : whatever is nard and why use it to anoint the Christ's feet ?

To properly grasp what nard is or was, one must look at its history and all the times it was mentioned. As far as we can tell around the Mediteranean Sea, Dioscorides spoke of nard in De Materia Medica. Of more than one actually. He lists a Syrian nard, an Indian nard and a Celtic nard. According to him, the Syrian nard got its name from the fact that it grows on the western slope of a mountain range -he was probably referring to the Hindu Kush. He also says its sweet aroma is close to that of nard from Cyprus. Indian nard is apparently smoother and more watery considering it grows in the Gange basin. The Celtic nard at last is both sweet and suave. He also mentions a wild nard growing in the mountains known already by the Gauls. As for Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History he lists a numerous variety of nards and one in particular that was so sweet-smelling that it was a most sought-after oil.

Roman literature is also a good resource when it comes to perfumes. In his Odes –the tenth to be more precise- Horace speaks of an « Assyrique nardo », Assyrian nard, whereas Petronius in his Cena Trimalchionis has one of his characters open an « ampullam nardi », a phial of nard, which was then rubbed on al the guests’ noses. Knowing the musty, musky scent of nard, one might be surprised upon reading so many lauds to it and the Roman nobility anointing their noses with it as they end a banquet. However, there happens to be mentions of nard in the Apicius, a Roman cookbook, according to which a few drops of nard might be useful to freshen a stale broth.

This occurrence of nard in a cookbook really raised our eyebrows and convinced us that nard was in fact lavender but how did the Romans end up confusing both ?

One must go back to the origins. Nard was named after the Assyrian city of Nuhadra –in actual Iraq- sitting on the banks of the Tigris river. Probably known for trading precious oils, one might say it was the starting point of spikenard trading routes going west into the Roman Empire although the nard existed way before the Romans. Already is it seen in a recipe for the anointing oil of Parthian kings as well as in Arrian’s Anabasis in a curious tale where the soldiers, as they traverse the desert of Gadrosia, find themselves trampling a « grass of nard » which then exhaled a sweet-smelling aroma. Research has now shown that this so-called nard was in fact…lemongrass.

To establish a link between the freshness of lemongrass and that of lavender isn’t much of a stretch.

Moreover, we looked for answers into the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which has gone uninterrupted since the early years of our era. After having ordered many an incense and nard-scented oils, we realised they were in fact all perfumed with lavender. Thus, we wondered why Mary-Magdalene anointed Jesus’ feet with nard –or lavender.

For so, let us dive into the writings. In the famous passage, St John writes : « nardou pistikes », « pure nard ». Some translated it into « true nard » as opposed to the fake one being lavender however we still think that « pistikes » has nothing to do with botanics. The Peshitta, an Aramaic translation of the Gospels, wrote : « dnardeen reeshaya ». Reeshaya here means « the best », of great quality. The symbolical use of the word reeshaya is most clearly seen in the Gospel of St Mark where Mary-Magdalene breaks « of pure nard. » on Jesus’ « head ». The Peshitta writes : « dnardeen reeshaya (…) al reesheh dyeshoo » a play on the words « reeshaya » which we’d roughly translate to : she poured the best on the Best.

Why pouring nard, though ? Or rather lavender ?

It is now known that myrrh is a symbol for death. It would thus have been very clever of Mary-Magdalene to anoint Jesus’ feet with it as a sign of his upcoming death and burial but she chose lavender. As such, her anointement is nothing short of a prophecy, lending us precious informations on the secret symbolism hidden behind lavender.

We read how the Ancients confused nard with lavender but we must now explain why they did so for they spoke of spikenard and lavender spike. The first bore its name from the fact its root looked like it was spiking out of the stem. The latter bore its name from its resemblance to an ear of wheat and this is precisely where we need investigate for therein lies the key to understanding the real meaning of lavender and solve a millenial controversy.

When Mary Magdalene poured lavender spike on Jesus’ feet, she accomplished a prophetic gesture of which she had probably no knowledge –as most prophecies in the New Testament. Along with St John whose head lies on Jesus’ chest - announcing the theosis- and the Virgin Mary who looked westward as her baby lay in her arms –announcing the Passion- Mary Magdalene announces the Passion and Resurrection. For as she poured the best on the Best, it is precisely the oil of the best ear of wheat which she poured upon He who compared himself to a « kernel of wheat ». This gesture is a clear reference to the words of Jesus saying on the eve of his death : « Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds »

The anointing of Jesus’ feet in the Gospel of Saint John heralds that of the myrrh-bearers and his Resurrection and of the Holy Spirit as it shone on his head upon his descent in the Hades, to a crown of light inextinguishable alike.

What we must understand is that lavender is akin to the light which shrouded the Christ as he went down into the Hades. Furthermore, mediaeval traditions will swiftly associate lavender to the virtue of keeping evil and dark spirits at bay. Lavender is a twig of life, fortifying the heart of Men ; it is the scent we smell as we leave a heartwarming feast, saying « I only hope it will give me as much pleasure when I'm dead as it does now when I'm alive. » It the the flower of foreseers, of those who see beyond appearances and the simple planes of existence.

The flower of they who want to trample and have trampled down death. The flower of soldiers as they traverse the desert, the flower of queens and kings chasing away all sorrows and withering of the soul.

Even more so than frankincense, lavender and its hues of violets and blues, is the perfect flower to connect us to the ethereal worlds. It clings to our soul and lifts it up and says to all and to us foremost that Love, over death, has won.

Your goodness and nard will follow me,

All the days of my life.

https://www.theperfumechronicles.com/chronicles/nard |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 13 de 24 de ce thème |

|

The Nard of Mary-Magdalene

My fools for senses,

Today, we shall be looking for an answer centuries of commentors failed to provide. Following our Review of Irrévérent and its unusual accord of oud and lavender, we decided to ponder awhile on this last ingredient which we thought we knew too well. Most of all, we wanted to envision it with a new eye : that of theology. Of history and literature and cooking and anthropology.

For indeed lavender passed through many cultures and through many readings did we stumble upon a most startling fact : that nard and lavender, in the Bible, are one. Thus, my fools for senses, let us discover today what really hid behind the Nard of Mary-Magdalene.

All good adventure movies start with a writing on a wall or in a book in our case. In the Bible, really. “Mary, having taken an ounce of pure nard anointed with it the feet of Jesus” This moving scene will very lively raise more than one question in the reader's mind : whatever is nard and why use it to anoint the Christ's feet ?

To properly grasp what nard is or was, one must look at its history and all the times it was mentioned. As far as we can tell around the Mediteranean Sea, Dioscorides spoke of nard in De Materia Medica. Of more than one actually. He lists a Syrian nard, an Indian nard and a Celtic nard. According to him, the Syrian nard got its name from the fact that it grows on the western slope of a mountain range -he was probably referring to the Hindu Kush. He also says its sweet aroma is close to that of nard from Cyprus. Indian nard is apparently smoother and more watery considering it grows in the Gange basin. The Celtic nard at last is both sweet and suave. He also mentions a wild nard growing in the mountains known already by the Gauls. As for Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History he lists a numerous variety of nards and one in particular that was so sweet-smelling that it was a most sought-after oil.

Roman literature is also a good resource when it comes to perfumes. In his Odes –the tenth to be more precise- Horace speaks of an « Assyrique nardo », Assyrian nard, whereas Petronius in his Cena Trimalchionis has one of his characters open an « ampullam nardi », a phial of nard, which was then rubbed on al the guests’ noses. Knowing the musty, musky scent of nard, one might be surprised upon reading so many lauds to it and the Roman nobility anointing their noses with it as they end a banquet. However, there happens to be mentions of nard in the Apicius, a Roman cookbook, according to which a few drops of nard might be useful to freshen a stale broth.

This occurrence of nard in a cookbook really raised our eyebrows and convinced us that nard was in fact lavender but how did the Romans end up confusing both ?

One must go back to the origins. Nard was named after the Assyrian city of Nuhadra –in actual Iraq- sitting on the banks of the Tigris river. Probably known for trading precious oils, one might say it was the starting point of spikenard trading routes going west into the Roman Empire although the nard existed way before the Romans. Already is it seen in a recipe for the anointing oil of Parthian kings as well as in Arrian’s Anabasis in a curious tale where the soldiers, as they traverse the desert of Gadrosia, find themselves trampling a « grass of nard » which then exhaled a sweet-smelling aroma. Research has now shown that this so-called nard was in fact…lemongrass.

To establish a link between the freshness of lemongrass and that of lavender isn’t much of a stretch.

Moreover, we looked for answers into the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which has gone uninterrupted since the early years of our era. After having ordered many an incense and nard-scented oils, we realised they were in fact all perfumed with lavender. Thus, we wondered why Mary-Magdalene anointed Jesus’ feet with nard –or lavender.

For so, let us dive into the writings. In the famous passage, St John writes : « nardou pistikes », « pure nard ». Some translated it into « true nard » as opposed to the fake one being lavender however we still think that « pistikes » has nothing to do with botanics. The Peshitta, an Aramaic translation of the Gospels, wrote : « dnardeen reeshaya ». Reeshaya here means « the best », of great quality. The symbolical use of the word reeshaya is most clearly seen in the Gospel of St Mark where Mary-Magdalene breaks « of pure nard. » on Jesus’ « head ». The Peshitta writes : « dnardeen reeshaya (…) al reesheh dyeshoo » a play on the words « reeshaya » which we’d roughly translate to : she poured the best on the Best.

Why pouring nard, though ? Or rather lavender ?

It is now known that myrrh is a symbol for death. It would thus have been very clever of Mary-Magdalene to anoint Jesus’ feet with it as a sign of his upcoming death and burial but she chose lavender. As such, her anointement is nothing short of a prophecy, lending us precious informations on the secret symbolism hidden behind lavender.

We read how the Ancients confused nard with lavender but we must now explain why they did so for they spoke of spikenard and lavender spike. The first bore its name from the fact its root looked like it was spiking out of the stem. The latter bore its name from its resemblance to an ear of wheat and this is precisely where we need investigate for therein lies the key to understanding the real meaning of lavender and solve a millenial controversy.

When Mary Magdalene poured lavender spike on Jesus’ feet, she accomplished a prophetic gesture of which she had probably no knowledge –as most prophecies in the New Testament. Along with St John whose head lies on Jesus’ chest - announcing the theosis- and the Virgin Mary who looked westward as her baby lay in her arms –announcing the Passion- Mary Magdalene announces the Passion and Resurrection. For as she poured the best on the Best, it is precisely the oil of the best ear of wheat which she poured upon He who compared himself to a « kernel of wheat ». This gesture is a clear reference to the words of Jesus saying on the eve of his death : « Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds »

The anointing of Jesus’ feet in the Gospel of Saint John heralds that of the myrrh-bearers and his Resurrection and of the Holy Spirit as it shone on his head upon his descent in the Hades, to a crown of light inextinguishable alike.

What we must understand is that lavender is akin to the light which shrouded the Christ as he went down into the Hades. Furthermore, mediaeval traditions will swiftly associate lavender to the virtue of keeping evil and dark spirits at bay. Lavender is a twig of life, fortifying the heart of Men ; it is the scent we smell as we leave a heartwarming feast, saying « I only hope it will give me as much pleasure when I'm dead as it does now when I'm alive. » It the the flower of foreseers, of those who see beyond appearances and the simple planes of existence.

The flower of they who want to trample and have trampled down death. The flower of soldiers as they traverse the desert, the flower of queens and kings chasing away all sorrows and withering of the soul.

Even more so than frankincense, lavender and its hues of violets and blues, is the perfect flower to connect us to the ethereal worlds. It clings to our soul and lifts it up and says to all and to us foremost that Love, over death, has won.

Your goodness and nard will follow me,

All the days of my life.

https://www.theperfumechronicles.com/chronicles/nard

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 14 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 15 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 16 de 24 de ce thème |

|

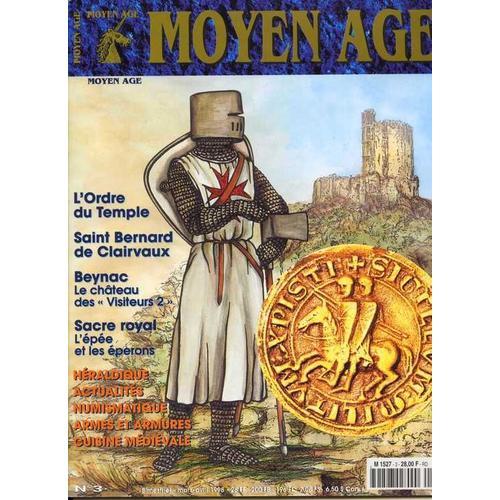

Bernard of Clairvaux

Above: Bernard of Clairvaux

by Alan Butler

Born Fontaine de Dijon France 1090

Died Clairvaux, near Troyes, Champagne France August 20th 1153

Bernard of Clairvaux may well represent the most important figure in Templarism. In our opinion past researchers have generally failed to credit St Bernard with the pivotal role he played in the planning, formation and promotion of the infant Templar Order. Whether an ‘intention’ to create an Order of the Templar sort existed prior to the life of St Bernard himself is a matter open to debate. (See ‘The Templar Continuum’ Butler and Dafoe, Templar Books 2,000).

The son of Tocellyn de Sorrell, Bernard was born into a middle-ranking aristocratic family, which held sway over an important region of Burgundy, though with close contacts to the region of Champagne. There is some dispute as to whether Bernard’s father had fought in the storming of Jerusalem in 1099, and indeed whether he died in the Levant. The question appears to be easily answered for in the small Templar type Church in St Bernard’s birthplace there is a marble plaque that states the Church was built by St Bernard’s mother in thanks for the safe return of her husband from the Crusade.

St Bernard was a younger member of an extremely large family. He appears to have received a good, standard education, at Chatillon-sur-Seine, which fitted him, most probably, for a life in the Church, which, of course, is exactly the direction he eventually took. Many stories exist regarding Bernard’s early years – his visions, torments and realisations. All of these were attributed to Bernard after his canonisation and therefore must surely be taken with a pinch of salt. What does seem evident is that Bernard was bright, inquisitive and probably tinged with a sort of genius. Certainly he was a fantastic organiser and possessed a charisma that few could deny.

St Bernard enters history in an indisputable sense at the age of 23 years, when together with a very large group of his brothers, cousins and maybe other kin, (probably between 25 and 30) he rode into the abbey of Citeaux, Dijon. This abbey was the first Cistercian monastery and had been set up somewhat earlier by a small band of dissident monks from Molesmes. Much can be found elsewhere in these pages relating specifically to the Cistercians. At the time of St Bernard’s arrival the abbey was under the guiding hand of Stephen, later St Stephen Harding, an Englishman.

Bernard announced his determination to follow the Cistercian way of life and together with his entourage he swamped the small abbey, swelling the number of brothers there to such an extent that it was inevitable that more abbeys would have to be formed.

Only three years later St Bernard, still an extremely young man, (25 years) was dispatched, together with a small band of monks, to a site at Clairvaux, near Troyes, in Champagne, there to become Abbott of his own establishment. It is known that the land upon which Clairvaux was built was donated by the Count of Champagne, based at the nearby city of Troyes.

St Bernard was a visionary, a man of apparently tremendous religious conviction. He could be irascible and domineering at times, but seems to have been generally venerated and well liked by those around him. Bernard suffered frequent bouts of ill health, almost from the moment he joined the Cistercians. This continued for the remainder of his life and may have demonstrated an inability on the part of his digestive system to cope with the severe diet enjoyed or rather endured by the Cistercians at the time.

Bernard’s influence grew within the established Church of his day. With a mixture of simple, religious zeal and some extremely important family connections, this little man involved himself in the general running, not only of the Cistercian Order, but the Roman Church of his day. Bernard was instrumental in the appointment of GREGORIO PAPARESCHI, Pope Innocent II in the year 1130, despite the fact that not all agencies supported the man for the Papal throne. Bernard walked hundreds of miles and talked to a great number of influential people in order to ensure Innocent’s ultimate acceptance. His success in this endeavour marked St Bernard as probably the most powerful man in Christendom, for as ‘Pope Maker’ he probably had more influence than the Pontiff himself.

This appointment should not be underestimated, for it was Pope Innocent II who formally accepted ‘The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon’ (The Knights Templar) into the Catholic fold. This he did, almost certainly, at the behest of Bernard and possibly as a result of promises he had made to this end at the time Bernard showed him the support which led to the Vatican.

To understand St Bernard’s importance to Cistercianism it is first necessary to study the Order in detail. In brief however it would be fair to suggest that Bernard’s own personality, drive and influence saw the Cistercians growing from a slightly quirky fringe monastic institution to being arguably the most significant component of Christian monasticism that the Middle Ages ever knew.

In addition to this St Bernard consorted with Princes, Kings and Pontiffs, even directly ‘creating’ his own Pope, BERNARDO PAGANELLI DI MONTEMAGNO (Eugnius III) who became Pontiff in 1145. This man had been a noviciate of St Bernard at Clairvaux and was, in all respects, St Bernard’s own man. From this point barely a decision was made in Rome that was not influenced in some way by St Bernard himself.

Much could be written about the ‘nature’ of St Bernard. He was a staunch supporter of the Virgin Mary, a visionary and a man who had a profound belief in an early and very ‘Culdean’ form of Christianity. This is exemplified by the short verse he once wrote.

‘Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.’

St Bernard staunchly supported what amounted to an utter veneration of the Virgin Mary for the whole of his life and was also an enthusiastic supporter of a rather strange little extract from the Old Testament, entitled ‘Solomon’s Song of Songs’.

How and why St Bernard became involved in the formation of the Knights Templar may never be fully understood. There is no doubt that he was blood-tied to some of the first Templar Knights, in particular Andre de Montbard, who was his maternal uncle. He may also have been related to the Counts of Champagne, who themselves appear to have been pivotal in the formation of the Templar Order.

For whatever reason St Bernard wrote the first ‘rules’ of the Templar Order. He may have undertaken this task personally and they were based, almost entirely, on the Order adopted by the Cistercians themselves. The Templars were officially declared to be a monastic order under the protection of Church in Troyes in 1139. Bernard went further and insisted that Pope Innocent II recognised this infant order as being solely under the authority of the Pope and no other temporal or ecclesiastical authority. It is a fact that the Templars venerated St Bernard from that moment on, until their own demise in 1307. St Bernard’s influence on the Templars is therefore pivotal to the whole of the movement’s aims and objectives and in our opinion no researcher should ever underestimate Bernard’s importance with this regard.

St Bernard travelled extensively, negotiated in civil disturbances and, surprisingly for the period, was instrumental in preventing a number of pogroms taking place against Jews in various locations within what is present day France. A staunch supporter of an Augustinian view of the mystery of the Christian faith, St Bernard was fiercely opposed to ‘rationalistic’ views of Christianity. In particular he was a staunch opponent of the dialectician ‘Peter Abelard’, a man whom St Bernard virtually destroyed when Abelard refused to accept Bernard’s own criticism of his radical ideas.

Although travelling extensively on many and varied errands during his life, St Bernard always returned to his own abbey of Clairvaux, which it seems (to us at least) had been deliberately built in a location that allowed free travel in all directions. It is suggested that Clairvaux was peopled with all manner of scholars, some of whom may well have been Jewish scribes. It is also true to say that if Citeaux remained the ‘head’ of the Cistercian movement during the life of St Bernard, Clairvaux lay at its heart. Clairvaux became the Mother House of many new Cistercian monasteries, not least of all Fountaines Abbey in Yorkshire, England, which itself was to rise to the rank of most prosperous abbey on English soil.

St Bernard died in Clairvaux on August 20th 1153, a date that would soon become his feast day, for St Bernard was canonised within a few short years of his death. Space here does not permit a full handling of this extraordinary man’s life or his interest in so many subjects, including architecture, music and (probably) ancient manuscripts. After his death a cult of St Bernard rapidly developed. At the time of the French Revolution St Bernard’s skull was taken for safekeeping to Switzerland, eventually finding its way back to Troyes. It is now housed in the Treasury of Troyes Cathedral and can be seen there, together with the skull and thighbone of St Malachy, a friend and contemporary of St Bernard.

A much fuller and more comprehensive detailed biography of St Bernard’s life can be found in ‘The Knights Templar Revealed’ Butler and Dafoe, Constable and Robinson – 2006.

About Us

TemplarHistory.com was started in the fall of 1997 by Stephen Dafoe, a Canadian author who has written several books on the Templars and related subjects.

Read more from our Templar History Archives – Templar History

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 17 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 18 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 19 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 20 de 24 de ce thème |

|

| Enviado: 21/10/2024 10:30 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 21 de 24 de ce thème |

|

Hugo de Payns o Payens (castillo de Payns, cerca de Troyes, Francia 9 de febrero de 1070-Reino de Jerusalén, 24 de mayo de 1136) fue el fundador y primer maestro de los Caballeros templarios y uno de los primeros nueve caballeros. En asociación con Bernardo de Claraval, creó la Regla latina, el código de conducta de la Orden.

Hijo de Gautier de Montigny y nieto de Hugo I, Señor de Payns, su infancia y su juventud se ven influidas por el ambiente de reforma religiosa que se desarrolla en la Champaña y que dará figuras de la talla de san Roberto de Molesmes, fundador de las abadías de Molesmes y Cîteaux, o la de san Bernardo de Claraval, impulsor de la reforma del cister y mentor eclesiástico de la misma Orden del Temple.

De la ferviente pasión religiosa de Hugo II de Payns es muestra su breve paso como monje por la abadía de Molesmes, tras la muerte de su primera esposa Emelina de Touillon, con la que se había desposado hacia el 1090. Fruto de este matrimonio nació su hija Odelina, futura señora de Ervy.

Vasallo fiel del conde Hugo I de Champaña,1 Hugo II de Payns abandona los hábitos y a partir del año 1100 se integra plenamente como uno de los principales miembros de la Corte champañesa, uniendo en su persona el señorío de Montigny y el de Payns.

Es muy probable que Hugo II de Payns realizara su primer viaje a Tierra Santa junto al conde de Champaña en 1104-1107. Tras regresar de este, y para ayudar a consolidar las pretensiones políticas de su señor, casó en segundas nupcias con Isabel de Chappes (entre 1107 y 1111), perteneciente a una de las familias más importantes del sur de la Champaña. Del matrimonio nacieron cuatro hijos: Teobaldo, futuro Abad de Santa Colombe de Sens; Guido Bordel de Payns, heredero del señorío; Guibuin, vizconde de Payns, y Herberto, llamado el ermitaño. Sin embargo, la pasión religiosa que sentía le llevó a tomar votos de castidad en 1119 y a partir nuevamente a Tierra Santa, donde creó, un año más tarde, la que llegaría a ser la Orden Militar más importante de la Cristiandad: La Orden del Temple.

Se afirma[cita requerida] que los otros caballeros eran Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, Archambaudo de Saint Agnan, Andrés de Montbard (tío materno de San Bernardo de Claraval), Godofredo Bison, y otros dos de los que solo se conoce su nombre, Rolando y Gondamero. Se desconoce el nombre del noveno caballero, aunque hay quien piensa que pudo ser Hugo, conde de Champaña.

En 1127 Hugo II de Payns regresa a Europa acompañado por Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, y dos hermanos más, de nombre Raúl y Juan, con el fin de reclutar nuevos miembros para la Orden, tomar posesión de las numerosas donaciones que habían sido otorgadas a esta y para organizar las primeras encomiendas de la Orden en Occidente (casi todas ellas en la región de la Champaña). Así pues, Hugo inicia un periplo que le lleva por Roma - a fin de solicitar del papa Honorio II un reconocimiento oficial de la Orden y la convocatoria de un concilio que debatiera el asunto - la Champaña (otoño de 1127); Anjou y Poitou (abril y mayo de 1128), Normandia, Inglaterra y Escocia (verano de 1128) y Flandes (otoño de 1128).

Hugo y sus compañeros regresan en enero de 1129 a la Champaña para tomar parte en el Concilio de Troyes, un concilio de la Iglesia católica, que se convocó en la ciudad francesa el 13 de enero de 1129, con el principal objeto de reconocer oficialmente a la Orden del Temple. En dicho concilio estuvieron presentes: el cardenal Mateo de Albano (representante del Papa); el arzobispo de Reims y el de Sens; diez obispos; ocho abades cistercienses de las abadías de Vézelay, Cîteaux, Clairvaux (que en este caso no era otro sino San Bernardo), Pontigny, Troisfontaines y Molesmes; y algunos laicos entre los que destacan Teobaldo II de Champaña, el conde de Campaña, André de Baudemont, el senescal de Champaña, el conde de Nevers y un cruzado de la campaña de 1095.

Hugo de Payns relató en este concilio los humildes comienzos de su obra, que en ese momento solo contaba con nueve caballeros, y puso de manifiesto la urgente necesidad de crear una milicia capaz de proteger a los cruzados y, sobre todo, a los peregrinos a Tierra Santa, y solicitó que el concilio deliberara sobre la constitución que habría que dar a dicha Orden.

Se encargó a San Bernardo, abad de Claraval, y a un clérigo llamado Jean Michel la redacción de una regla durante la sesión, que fue leída y aprobada por los miembros del concilio.

Tras el concilio de Troyes, Hugo II de Payns nombró a Payen de Montdidier Maestre Provincial de las encomiendas sitas en territorio francés y en flandes, y a Hugo de Rigaud Maestre Provincial para los territorios del Languedoc, la Provenza y los reinos cristianos hispánicos y tras ello, regresó a Jerusalén dirigiendo la Orden que el mismo había creado durante casi veinte años hasta su muerte en el año 1136 (el 24 de mayo según el obituario del templo de Reims), haciendo de ella una influyente institución militar y financiera internacional.

Un cronista del siglo XVI escribió que fue enterrado en la Iglesia de San Jaime de Ferrara.2

No hay un retrato contemporáneo de él.

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 22 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 23 de 24 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 24 de 24 de ce thème |

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

|

|

|

Premier Premier

Précédent

10 a 24 de 24

Suivant Précédent

10 a 24 de 24

Suivant

Dernier

Dernier

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Tous droits réservés | |

|

|

![Regreso Al Fururo III (Back To The Future III) [1990] –, 40% OFF](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BYzgzMDc2YjQtOWM1OS00ZjhhLWJiNjQtMzE3ZTY4MTZiY2ViXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNDQ0MTYzMDA@._V1_.jpg)