|

|

General: DOCTOR BROWN 1.21 GIGAWATTS GREAT SCOTT SCOTLAND/JAMES WATT/TRANSFIGURATION

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

The lost history of the Freemasons

Amanda Ruggeri

Features correspondent

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Conspiracy theories abound about the Freemasons. But Scotland’s true Masonic history, while forgotten by many for centuries, remains hidden in plain sight.

With its cobblestone paving and Georgian façades, tranquil Hill Street is a haven in Edinburgh’s busy New Town. Compared to the Scottish capital’s looming castle or eerie closes, it doesn’t seem like a street with a secret.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Tranquil and historic, Edinburgh’s Hill Street attracts few tourists (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Walk slowly, though, and you might notice something odd. Written in gold gilt above a door framed by two baby-blue columns are the words, “The Lodge of Edinburgh (Mary’s Chapel) No 1”. Further up the wall, carved into the sandstone, is a six-pointed star detailed with what seem – at least to non-initiates – like strange symbols and numbers.

Located at number 19 Hill Street, Mary’s Chapel isn’t a place of worship. It’s a Masonic lodge. And, with its records dating back to 1599, it’s the oldest proven Masonic lodge still in existence anywhere in the world.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

At 19 Hill Street, look up to see this six-pointed star, a Masonic symbol (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That might come as a surprise to some people. Ask most enthusiasts when modern Freemasonry began, and they’d point to a much later date: 1717, the year of the foundation of what would become known as the Grand Lodge of England. But in many ways, Freemasonry as we know it today is as Scottish as haggis or Harris tweed.

From the Middle Ages, associations of stonemasons existed in both England and Scotland. It was in Scotland, though, that the first evidence appears of associations – or lodges – being regularly used. By the late 1500s, there were at least 13 established lodges across Scotland, from Edinburgh to Perth. But it wasn’t until the turn of the 16th Century that those medieval guilds gained an institutional structure – the point which many consider to be the birth of modern Freemasonry.

Take, for example, the earliest meeting records, usually considered to be the best evidence of a lodge having any real organisation. The oldest minutes in the world, which date to January 1599, is from Lodge Aitchison’s Haven in East Lothian, Scotland, which closed in 1852. Just six months later, in July 1599, the lodge of Mary’s Chapel in Edinburgh started to keep minutes, too. As far as we can tell, there are no administrative records from England dating from this time.

“This is, really, when things begin,” said Robert Cooper, curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland and author of the book Cracking the Freemason’s Code. “[Lodges] were a fixed feature of the country. And what is more, we now know it was a national network. So Edinburgh began it, if you like.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

The Grand Lodge of Scotland, also known as Freemasons Hall, stands in the heart of Edinburgh’s New Town (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

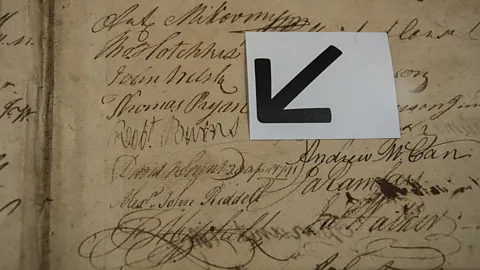

I met Cooper in his office: a wood-panelled, book-stuffed room in the Grand Lodge of Scotland at 96 George Street, Edinburgh – just around the corner from Mary’s Chapel. Here and there were cardboard boxes, the kind you’d use for a move, each heaped full with dusty books and records. Since its founding in 1736, this lodge has received the records and minutes of every other official Scottish Masonic lodge in existence. It is also meant to have received every record of membership, possibly upwards of four million names in total.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

One of the items on display at the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum is its membership record with the signature of famed Freemason Robert Burns (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That makes the sheer number of documents to wade through daunting. But it’s also fruitful, like when the Grand Lodge got wind of the Aitchison’s Haven minutes, which were going for auction in London in the late 1970s. Another came more recently when Cooper found the 115-year-old membership roll book of a Scottish Masonic lodge in Nagasaki, Japan.

“There’s an old saying that wherever Scots went in numbers, the first thing they did was build a kirk [church], then they would build a bank, then they would build a pub. And the fourth thing was always a lodge,” Cooper said, chuckling.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

The curator of the Grand Lodge of Scotland, Robert Cooper, looks over the lodge’s museum (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

That internationalism was on full display in the Grand Lodge of Scotland’s museum, which is open to the public. It was full of flotsam and jetsam from around the world: a green pennant embroidered with the “District Grand Lodge of Scottish Freemasonry in North China”; some 30 Masonic “jewels” – or, to non-Masons, medals – from Czechoslovakia alone.

Of course, conspiracy theorists find that kind of reach foreboding. Some say Freemasonry is a cult with links to the Illuminati. Others believe it to be a global network that’s had a secret hand in everything from the design of the US dollar bill to the French Revolution. Like most other historians, Cooper shakes his head at this.

“If we’re a secret society, how do you know about us?” he asked. “This is a public building; we’ve got a website, a Facebook page, Twitter. We even advertise things in the press. But we’re still a ‘secret society’ running the world! A real secret society is the Mafia, the Chinese triads. They are real secret societies. They don’t have a public library. They don’t have a museum you can wander into.”

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

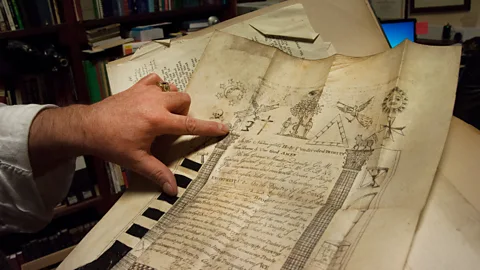

Cooper points to the Masonic symbols on one of the many historic documents in the lodge’s archive (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Some of the mythology about Freemasonry stems from the mystery of its early origins. One fantastical theory goes back to the Knights Templar; after being crushed by King Philip of France in 1307, the story goes, some fled to Argyll in western Scotland, and remade themselves as a new organisation called the Freemasons. (Find out more in our recent story about the Knights Templar).

Others – including Freemasons themselves – trace their lineage back to none other than King Solomon, whose temple, it’s said, was built with a secret knowledge that was transferred from one generation of stonemason to the next.

A more likely story is that Freemasonry’s early origins stem from medieval associations of tradesmen, similar to guilds. “All of these organisations were based on trades,” said Cooper. “At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’.”

At one time, it would have been, ‘Oh, you’re a Freemason – I’m a Free Gardener, he’s a Free Carpenter, he’s a Free Potter’ – Robert Cooper

For all of the tradesmen, having some sort of organisation was a way not only to make contacts, but also to pass on tricks of the trade – and to keep outsiders out.

But there was a significant difference between the tradesmen. Those who fished or gardened, for example, would usually stay put, working in the same community day in, day out.

Not so with stonemasons. Particularly with the rush to build more and more massive, intricate churches throughout Britain in the Middle Ages, they would be called to specific – often huge – projects, often far from home. They might labour there for months, even years. Thrown into that kind of situation, where you depended on strangers to have the same skills and to get along, how could you be sure everyone knew the trade and could be trusted? By forming an organisation. How could you prove that you were a member of that organisation when you turned up? By creating a code known by insiders only – like a handshake.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Edinburgh's Lodge of Journeyman Masons No. 8 was founded in 1578; this lodge was built for it on Blackfriars Street in 1870 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Even if lodges existed earlier, though, the effort to organise the Freemason movement dates back to the late 1500s. A man named William Schaw was the Master of Works for King James VI of Scotland (later also James I of England), which meant he oversaw the construction and maintenance of the monarch’s castles, palaces and other properties. In other words, he oversaw Britain’s stonemasons. And, while they already had traditions, Schaw decided that they needed a more formalised structure – one with by-laws covering everything from how apprenticeships worked to the promise that they would “live charitably together as becomes sworn brethren”.

In 1598, he sent these statutes out to every Scottish lodge in existence. One of his rules? A notary be hired as each lodge’s clerk. Shortly after, lodges began to keep their first minutes.

“It’s because of William Schaw’s influence that things start to spread across the whole country. We can see connections between lodges in different parts of Scotland – talking to each other, communicating in different ways, travelling from one place to another,” Cooper said.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

This oil painting at the Grand Lodge of Scotland shows Robert Burns’ inauguration at Lodge Canongate Kilwinning No. 2, which was founded in 1677 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s influence was soon overshadowed. With the founding of England’s Grand Lodge, the English edged out in front of the movement’s development. And in the centuries since, Freemasonry’s Scottish origins have been largely forgotten.

“The fact that England can claim the first move towards national organisation through grand lodges, and that this was copied subsequently by Ireland (c 1725) and Scotland (1736), has led to many English Masonic historians simply taking it for granted that Freemasonry originated in England, which it then gave to the rest of the world,” writes David Stevenson in his book The Origins of Freemasonry.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Hidden in plain sight on Brodie’s Close off of Edinburgh’s Royal Mile, the Celtic Lodge of Edinburgh and Leith No. 291 was founded in 1821 (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Cooper agrees. “It is in some ways a bit bizarre when you think of the fact that we have written records, and therefore membership details, and all the plethora of stuff that goes with that, for almost 420 years of Scottish history,” he said. “For that to remain untouched as a source – a primary source – of history is really rather odd.”

One way in which most people associate Freemasonry and Scotland, meanwhile, is Rosslyn Chapel, the medieval church resplendent with carvings and sculptures that, in the wake of Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code, many guides have explained as Masonic. But the building’s links to Masonry are tenuous. Even a chapel handbook published in 1774 makes no mention of any Masonic connections.

Amanda Ruggeri Amanda Ruggeri

Mary’s Chapel may only be open to fellow Freemasons, but its location is anything but a secret (Credit: Amanda Ruggeri)

Scotland’s true Masonic history, it turns out, is more hidden than the church that Dan Brown made famous. It’s just hidden in plain sight: in the Grand Lodge and museum that opens its doors to visitors; in the archivist eager for more people to look at the organisation’s historical records; and in the lodges themselves, tucked into corners and alleyways throughout Edinburgh and Scotland’s other cities.

Their doors may often be closed to non-members, but their addresses, and existence, are anything but secret.

This story is a part of BBC Britain – a series focused on exploring this extraordinary island, one story at a time. Readers outside of the UK can see every BBC Britain story by heading to the Britain homepage; you also can see our latest stories by following us on Facebook and .

If you liked this story, sign up for the weekly bbc.com features newsletter, called “If You Only Read 6 Things This Week”. A handpicked selection of stories from BBC Future, Earth, Culture, Capital, Travel and Autos, delivered to your inbox every Friday.

https://www.bbc.com/travel/article/20161209-secret-history-of-the-freemasons-in-scotland |

|

|

|

|

Columbus and the Templars

Was Columbus using old Templar maps when he crossed the Atlantic? At first blush, the navigator and the fighting monks seem like odd bedfellows. But once I began ferreting around in this dusty corner of history, I found some fascinating connections. Enough, in fact, to trigger the plot of my latest novel, The Swagger Sword.

To begin with, most history buffs know there are some obvious connections between Columbus and the Knights Templar. Most prominently, the sails on Columbus’ ships featured the unique splayed Templar cross known as the cross pattée (pictured here is the Santa Maria):

Additionally, in his later years Columbus featured a so-called “Hooked X” in his signature, a mark believed by researchers such as Scott Wolter to be a secret code used by remnants of the outlawed Templars (see two large X letters with barbs on upper right staves pictured below):

Other connections between Columbus and the Templars are less well-known. For example, Columbus grew up in Genoa, bordering the principality of Seborga, the location of the Templars’ original headquarters and the repository of many of the documents and maps brought by the Templars to Europe from the Middle East. Could Columbus have been privy to these maps? Later in life, Columbus married into a prominent Templar family. His father-in-law, Bartolomeu Perestrello (a nobleman and accomplished navigator in his own right), was a member of the Knights of Christ (the Portuguese successor order to the Templars). Perestrello was known to possess a rare and wide-ranging collection of maritime logs, maps and charts; it has been written that Columbus was given a key to Perestrello’s library as part of the marriage dowry. After marrying, Columbus moved to the remote Madeira Islands, where a fellow resident, John Drummond, had also married into the Perestrello family. Drummond was a grandson of Scottish explorer Prince Henry Sinclair, believed to have sailed to North America in 1398. It is, accordingly, likely that Columbus had access to extensive Templar maps and charts through his familial connections to both Perestrello and Drummond.

Another little-known incident in Columbus’ life sheds further light on the navigator’s possible ties to the Templars. In 1477, Columbus sailed to Galway, on the west coast of Ireland, from where the legendary Brendan the Navigator supposedly set sale in the 6th century on his journey to North America. While there, Columbus prayed at St. Nicholas’ Church, a structure built over an original Templar chapel dating back to around the year 1300. St. Nicholas’ Church has been compared by some historians to Scotland’s famous Roslyn Chapel, complete with Templar tomb, Apprentice Pillar, and hidden Templar crosses. (Recall that Roslyn Chapel was built by another grandson—not Drummond—of the aforementioned Prince Henry Sinclair.) According to his diary, Columbus also famously observed “Chinese” bodies floating into Galway harbor on driftwood, which may have been what first prompted him to turn his eyes westward. A granite monument along the Galway waterfront, topped by a dove (Columbus meaning ‘dove’ in Latin), commemorates this sighting, the marker reading: On these shores around 1477 the Genoese sailor Christoforo Colombo found sure signs of land beyond the Atlantic.

In fact, as the monument text hints, Columbus may have turned more than just his eyes westward. A growing body of evidence indicates he actually crossed the north Atlantic in 1477. Columbus wrote in a letter to his son: “In the year 1477, in the month of February, I navigated 100 leagues beyond Thule [to an] island which is as large as England. When I was there the sea was not frozen over, and the tide was so great as to rise and fall 26 braccias.” We will turn later to the mystery as to why any sailor would venture into the north Atlantic in February. First, let’s examine Columbus’ statement. Historically, ‘Thule’ is the name given to the westernmost edge of the known world. In 1477, that would have been the western settlements of Greenland (though abandoned by then, they were still known). A league is about three miles, so 100 leagues is approximately 300 miles. If we think of the word “beyond” as meaning “further than” rather than merely “from,” we then need to look for an island the size of England with massive tides (26 braccias equaling approximately 50 feet) located along a longitudinal line 300 miles west of the west coast of Greenland and far enough south so that the harbors were not frozen over. Nova Scotia, with its famous Bay of Fundy tides, matches the description almost perfectly. But, again, why would Columbus brave the north Atlantic in mid-winter? The answer comes from researcher Anne Molander, who in her book, The Horizons of Christopher Columbus, places Columbus in Nova Scotia on February 13, 1477. His motivation? To view and take measurements during a solar eclipse. Ms. Molander theorizes that the navigator, who was known to track celestial events such as eclipses, used the rare opportunity to view the eclipse elevation angle in order calculate the exact longitude of the eastern coastline of North America. Recall that, during this time period, trained navigators were adept at calculating latitude, but reliable methods for measuring longitude had not yet been invented. Columbus, apparently, was using the rare 1477 eclipse to gather date for future western exploration. Curiously, Ms. Molander places Columbus specifically in Nova Scotia’s Clark’s Bay, less than a day’s sail from the famous Oak Island, legendary repository of the Knights Templar missing treasure.

The Columbus-Templar connections detailed above were intriguing, but it wasn’t until I studied the names of the three ships which Columbus sailed to America that I became convinced the link was a reality. Before examining these ship names, let’s delve a bit deeper into some of the history referred to earlier in this analysis. I made a reference to Prince Henry Sinclair and his journey to North American in 1398. The Da Vinci Code made the Sinclair/St. Clair family famous by identifying it as the family most likely to be carrying the Jesus bloodline. As mentioned earlier, this is the same family which in the mid-1400s built Roslyn Chapel, an edifice some historians believe holds the key—through its elaborate and esoteric carvings and decorations—to locating the Holy Grail. Other historians believe the chapel houses (or housed) the hidden Knights Templar treasure. Whatever the case, the Sinclair/St. Clair family has a long and intimate historical connection to the Knights Templar. In fact, a growing number of researchers believe that the purpose of Prince Henry Sinclair’s 1398 expedition to North America was to hide the Templar treasure (whether it be a monetary treasure or something more esoteric such as religious artifacts or secret documents revealing the true teachings of the early Church). Researcher Scott Wolter, in studying the Hooked X mark found on many ancient artifacts in North American as well as on Columbus’ signature, makes a compelling argument that the Hooked X is in fact a secret symbol used by those who believed that Jesus and Mary Magdalene married and produced children. (See The Hooked X, by Scott F. Wolter.) These believers adhered to a version of Christianity which recognized the importance of the female in both society and in religion, putting them at odds with the patriarchal Church. In this belief, they had returned to the ancient pre-Old Testament ways, where the female form was worshiped and deified as the primary giver of life.

It is through the prism of this Jesus and Mary Magdalene marriage, and the Sinclair/St. Clair family connection to both the Jesus bloodline and Columbus, that we now, finally, turn to the names of Columbus’ three ships. Importantly, he renamed all three ships before his 1492 expedition. The largest vessel’s name, the Santa Maria, is the easiest to analyze: Saint Mary, the Virgin Mary, the mother of Jesus. The Pinta is more of a mystery. In Spanish, the word means ‘the painted one.’ During the time of Columbus, this was a name attributed to prostitutes, who “painted” their faces with makeup. Also during this period, the Church had marginalized Mary Magdalene by referring to her as ‘the prostitute,’ even though there is nothing in the New Testament identifying her as such. So the Pinta could very well be a reference to Mary Magdalene. Last is the Nina, Spanish for ‘the girl.’ Could this be the daughter of Mary Magdalene, the carrier of the Jesus bloodline? If so, it would complete the set of women in Jesus’ life—his mother, his wife, his daughter—and be a nod to those who opposed the patriarchy of the medieval Church. It was only when I researched further that I realized I was on the right track: The name of the Pinta before Columbus changed it was the Santa Clara, Portuguese for ‘Saint Clair.’

So, to put a bow on it, Columbus named his three ships after the Virgin Mary, Mary Magdalene, and the carrier of their bloodline, the St. Clair girl. These namings occurred during the height of the Inquisition, when one needed to be extremely careful about doing anything which could be interpreted as heretical. But even given the danger, I find it hard to chalk these names up to coincidence, especially in light of all the other Columbus connections to the Templars. Columbus was intent on paying homage to the Templars and their beliefs, and found a subtle way of renaming his ships to do so.

Given all this, I have to wonder: Was Columbus using Templar maps when he made his Atlantic crossing? Is this why he stayed south, because the maps showed no passage to the north? If so, and especially in light of his 1477 journey to an area so close to Oak Island, what services had Columbus provided the Templars in exchange for these priceless charts?

It is this research, and these questions, which triggered my novel, The Swagger Sword. If you appreciate a good historical mystery as much as I, I think you’ll enjoy the story.

|

|

|

|

|

Evidence the Knights Templar got to America!

The latest episode of Templar Knight TV looks at claims the Knights Templar got to America. It’s alleged they managed to do this a hundred years before Christopher Columbus reached the New World. But is there any truth to this?

The story starts with the Templars’ demise. It’s 1307 and they are being rounded up, imprisoned and some are burned to death. Little wonder some Knights Templar may have fled. A popular theory runs that when word got out that they were doomed, some knights transported treasure from the Paris Temple to the port of La Rochelle. From there, ships took the surviving Templars to Scotland. And then what happened?

Well, I was involved in a programme last year called America Unearthed presented by Scott Wolter. He is a forensic geologist and his analysis of rock carvings in the United States and Scotland has convinced him the knights made the long journey. With the help of a Scottish aristocrat called Henry Sinclair, they crossed the Atlantic to Nova Scotia.

As you will all know, proof that the Knights Templar got to America is offered in the form of items found at Oak Island in Nova Scotia; an enigmatic tower at Newport, Rhode Island and what is claimed to be the engraving of a knight in Westford, Massachusetts. But sceptics abound. They’re not convinced by the Money Pit at Oak Island, think the Newport Tower is a 17th century windmill and that the Westford Knight is a trick of the eye on a glacial boulder.

FIND OUT MORE: Did the Knights Templar take the Holy Grail to America?

As for the Sinclair connection, sceptics point out that these Scottish nobles testified against the Templars at their trial. Far from being good friends and allies of the knights, they had little sympathy and turned on them in their hour of need.

DISCOVER: The Westford Knight is disappearing!

Nevertheless, the argument rages on that the Knights Templar got to America. I go to Rosslyn chapel where some have pointed to images that look like maize – a crop that didn’t exist in the Old World before Columbus. And in the basement sacristy, lines on the wall are claimed to be a map. I had exclusive access when the chapel was empty to film for myself and you can see what I found.

I do hope you can spare a quarter of an hour to get your weekly Templar dose!

https://thetemplarknight.com/2020/09/15/knights-templar-america/ |

|

|

|

|

Our 26th President Teddy Roosevelt was a Freemason.

He is Honored with a Memorial in Washington D.C. on an Island in the Potomac River. The Island was once called "MY LORDS ISLAND" and was known as "MASON ISLAND".

An interesting alignment occurs when a map of Washington DC is viewed looking to the EAST...

Place two diagrams of the Great Pyramid (with slopes of 51.51) on the map of DC with their corners touching and resting on the Roosevelt Memorial on "MASON ISLAND" ---

|

|

|

|

|

-AA+A

1911–1915, John Russell Pope. 1733 16th St. NW

(Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Scottish Rite Temple (Franz Jantzen)

☰ SEE METADATA

The mausoleum at Halikarnassos (353–c. 340 b.c.e.) was a model for many buildings in this period, including Masonic temples, because as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world it was associated with the beginnings of Western architectural traditions. The origins of freemasonry are linked to the lodges of medieval stonemasons and with a practice of architecture based on fundamental rules of the universe, with its most esoteric aspects expressed through a language of symbols. The definition of freemasonry as “a peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory, and illustrated by symbols” explains why the buildings housing such organizations are themselves expressive of symbolic meaning.

Thrown down by an earthquake in the thirteenth century and quarried in the sixteenth century by the Knights of Saint John for the building of one of their castles, King Mausolos's tomb, a Hellenistic monument located on the Turkish coast, was the subject of numerous reconstructions by historians, archaeologists, and architects based on two ancient texts that describe its huge dimensions, colonnaded base, and stepped pyramidal top supporting a quadriga.

John Russell Pope's design, based on Newton and Pullman's 1862 restoration of the mausoleum, is centered on a nearly square site (217.5 by 212 feet) and raised above 16th Street on a podium with steps that extend the width of the block and that are organized according to arcane numerology. Three, five, seven, and nine steps converge on the central entry, which is guarded by Sphinxes, sculpted by Adolph A. Weinman, representing wisdom and power, contemplation and action. Thirty-six Ionic columns 33 feet high circumscribe the temple room, where the highest degree of freemasonry (the thirty-third) is conferred. The attic, marked by acroteria and the stepped pyramid, covers a square Guastavino dome; thus, the basic form above the base encloses a single volume. The compact base, with its expanses of smooth walls broken only by windows and doors, the peripteral colonnade set against nearly solid walls, and the faceted surfaces of the roof demonstrate Pope's unerring sense of balanced proportional relationships between masses and details. The light, monochromatic Indiana limestone is particularly well suited to the combination of planar surfaces and finely carved Greek and Egyptian details. Although Pope, with the advice of local architect and mason Elliott Woods, was responsible for incorporating some basic symbolism, the inscriptions and symbolic decorative details were planned by the grand commander of the lodge, George Fleming Moore, after the architectural design was completed.

The ground story is represented by the monolithic base on the exterior; on the interior an apsed atrium is ringed by offices, meeting rooms, banquet hall, and libraries. The atrium's form and decoration were intended as symbolic imitation of a Roman impluvium. Two sets of four massive Doric columns in a highly polished green Windsor, Vermont, granite establish a pathway leading to the apse on the east, where the main stair rises to the temple room. The oak-beam ceiling is painted in deep shades of red, brown, blue, yellow, and green, as are the walls in recesses behind the column screens. The decorative vocabulary mixes Greek frieze motifs and Egyptian hieroglyphics. The variation of rich and beautifully crafted materials continues in the main space. The temple room, a square with beveled corners that continue up into the dome, is constructed of limestone walls, Botticino marble dado, black and white marble floors, and a Guastavino tile dome. Windows are screened by Ionic columns set in antis made of green Windsor, Vermont, granite. Their gilded bronze capitals and bases echo the lavish use of gold or bronze in the entablature, windows, screens, and doors. The vault nearly doubles the height of the room, a proportional relationship that complements the subdued richness of the architectural surface. American architectural critic Aymar Embury so admired Pope's Scottish Rite Temple that he maintained, “Roman architects of two thousand years ago would prefer [it] to any of their own work.” 43

https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/DC-01-MH12 |

|

|

|

|

Madeleine de France, Queen of Scotland, 1536

(Madeleine de France (1520-37) Queen of Scotland, 1536 )

|

https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Corneille-de-Lyon/80721/Madeleine-de-France,-Queen-of-Scotland,-1536.html

|

|

|

|

|

Madeleine of Valois

Madeleine of Valois (10 August 1520 – 7 July 1537) was a French princess who briefly became Queen of Scotland in 1537 as the first wife of King James V. The marriage was arranged in accordance with the Treaty of Rouen, and they were married at Notre-Dame de Paris in January 1537, despite French reservations over her failing health. Madeleine died in July 1537, only six months after the wedding and less than two months after arriving in Scotland, resulting in her nickname, the "Summer Queen".

Madeleine (back right) with her mother and sisters, from the Book of Hours of Catherine de'Medici.

Madeleine was born at the Chteau de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, the fifth child and third daughter of King Francis I of France and Claude, Duchess of Brittany, herself the eldest daughter of King Louis XII of France and Anne, Duchess of Brittany.

She was frail from birth, and grew up in the warm and temperate Loire Valley region of France, rather than at Paris, as her father feared that the cold would destroy her delicate health. Together with her sister, Margaret, she was raised by her aunt, Marguerite de Navarre until her father remarried and his new wife, Eleanor of Austria, took them into her own household.[1] By her sixteenth birthday, she had contracted tuberculosis.[2]

Marriage negotiations

[edit]

Three years before Madeleine's birth, the Franco-Scottish Treaty of Rouen was made to bolster the Auld Alliance after Scotland's defeat at the Battle of Flodden. A marriage between a French princess and the Scottish King was one of its provisions.[3] In April 1530, John Stewart, Duke of Albany, was appointed commissioner to finalize the royal marriage between James V and Madeleine.[4] However, as Madeleine did not enjoy good health, another French bride, Mary of Bourbon, was proposed.[5]

James V sent his herald James Atkinhead to see Mary of Bourbon,[6] and a contract was made for James to marry her. King James travelled to France in 1536 to meet Mary of Bourbon, but smitten with the delicate Madeleine, he asked Francis I for her hand in marriage. Fearing the harsh climate of Scotland would prove fatal to his daughter's already failing health, Francis I initially refused to permit the marriage.[7]

James V met Francis I and the French royal household between Roanne and Lyon on 13 October.[8] He continued to press Francis I for Madeleine's hand, and despite his reservations and nagging fears, Francis I reluctantly granted permission to the marriage only after Madeleine made her interest in marrying James very obvious. The court moved down the Loire Valley to Amboise, and to the Chteau de Blois, and the marriage contract was signed on 26 November 1536.[9]

Wedding at Notre-Dame

[edit]

Notre-Dame de Paris Notre-Dame de Paris and its environs, known as the Parvis, Jean Marot, 17th century

In preparation for the wedding, Francis I bought clothes and furnishings for Madeleine; jewels and gold chains were supplied by Regnault Danet, linen and cloths by Marie de Genevoise and Phillipe Savelon, clothes by the tailors Marceau Goursault and Charles Lacquait, veils by Jean Guesdon, and trimmings by Victor de Laval, who also made passementerie for a bed that Francis gave the couple. The goldsmith Thibault Hotman made silver plate for Madeleine.[10][11] The merchants of the royal "argenterie", René Tardif and Robert Fichepain supplied silks and woollen cloth.[12] A quantity of gold and silver trimmings for embroidering the clothes of Madeleine and her ladies were ordered from Baptiste Dalverge, a wire-drawer.[13] A platform walkway was constructed from the Bishop's Palace to Notre-Dame de Paris.[14]

After a Royal Entry into Paris on 31 December 1536,[15] they were married at Notre-Dame on 1 January 1537.[2] There was a banquet that night in the Great Hall of the Palais de la Cité.[16] Over the next two weeks there were further celebrations and tournaments at the Chteau de la Tournelle and Louvre.[17] The wedding festivities in 1537 were similar to those of 24 April 1558, for the wedding of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Francis, Dauphin of France.[18]

Francis I provided Madeleine with a generous dowry of 100,000 écu, and a further 30,000 francs settled on James V. According to the marriage contract made at Blois, Madeleine renounced her and any of her heirs' claims to the French throne. If James died first, Madeleine would retain for her lifetime assets including the Earldoms of Fife, Strathearn, Ross, and Orkney with Falkland Palace, Stirling Castle, and Dingwall Castle, with the Lordship of Galloway and Threave Castle.[19]

Coat of arms of Madeleine of Valois as Queen consort of Scots

In February the couple moved to Chantilly, to Senlis and Compiègne, where James received the Papal gift of hat and sword.[20][21][22] They stayed two nights at the Chteau de La Roche-Guyon.[23] After months of festivities and celebrations, the couple left France for Scotland from Le Havre in May 1537. The French ships were commanded by Jacques de Fountaines, Sieur de Mormoulins.[24] On 15 May, English sailors sold fish to the Scottish and French fleet off Bamburgh Head.[25] Madeleine's health deteriorated even further, and she was very sick when the royal pair landed in Scotland. They arrived at Leith at 10 o'clock on Whitsun-eve, 19 May 1537.[26]

According to John Lesley the ships were laden with her possessions;

"besides the Quenes Hienes furnitour, hinginis, and appareill, quhilk wes schippit at Newheavin and careit in Scotland, was also in hir awin cumpanye, transportit with hir majestie in Scotland, mony costlye jewells and goldin wark, precious stanis, orient pearle, maist excellent of any sort that was in Europe, and mony coistly abilyeaments for hir body, with mekill silver wark of coistlye cupbordis, cowpis, & plaite."[27]

A list or inventory of wedding presents from Francis I also survives, including Arras tapestry, cloths of estate, rich beds, two cupboards of silver gilt plate, table carpets, and Persian carpets.[28][29] Francis I also gave James V three of the ships, the Salamander, Morsicher, and Great Unicorn.[30] Madeleine took up residence at Holyrood Palace on 21 May 1537.[31]

French household in Scotland

[edit]

The French courtiers who came with her to Scotland to form her household included; her former governess, Anne de Boissy Gouffier, Madame de Montreuil; Anne de Viergnon, Madame de Bren or Bron; Anne Le Maye; Marguerite de Vergondois her chamberer; Marion Truffaut, her nurse; her secretary, Jean de Langeac, Bishop of Limoges; master household, Jean de St Aubin; squires and cupbearers Charles de Marconnay and Charles du Merlier; the physician Master Partix; pages John Crammy and Pierre de Ronsard; furrier Gillan; butcher John Kenneth; barber Anthony.[32][33][34] A physician from Paris, Jacques Lecoq, set out later to join her in Scotland.[35]

Madeleine wrote to her father from Edinburgh on 8 June 1537 saying that she was better and her symptoms had diminished. James V had written to Francis I asking him to send the physician Master Francisco, and Madeleine wrote that he was now needed only to perfect her cure. She signed this letter "Magdalene de France".[36] However, a month later, on 7 July 1537, (a month before her 17th birthday), Madeleine, the so-called "Summer Queen" of Scots, died in her husband's arms at Holyrood Palace.[37]

James V wrote to Francis I informing him of his daughter's death.[38] He called Madeleine "my dear companion" – votre fille, ma trés chére compaigne.[39]

Queen Madeleine was interred in Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, next to King James II of Scotland. Black mourning clothes were worn at her funeral, and an order was sent to the merchants of Dundee to provide black cloth. Her household servants were provided with "dule gowns", and horses at the procession had black cloths and trappings.[40][41] The chapel at Holyrood Palace was draped with cloth from Milan.[42] The grave was desecrated by a mob in 1776 and her allegedly still beautiful head was stolen.[43]

One of her gentlewomen, Madame de Montrueil or Motrell, visited London on her way back to France. She said that Madeleine "had no good days after her arrival there (in Scotland), but always sickly with a catarrh which descended into her stomach, which was the cause of her death".[44]

An inventory made of the king's goods in 1542 includes some of her clothes, furnishings for her chapel, six stools for her gentlewomen to sit upon, and gold cups and other items made for her when she was a child.[45]

Madeleine's marriage and death were commemorated by the poet David Lyndsay's Deploration of Deith of Quene Magdalene; the poem describes the pageantry of the marriage in France and Scotland:

O Paris! Of all citeis principall!

Quhilk did resave our prince with laud and glorie,

Solempnitlie, throw arkis triumphall. [arkis = arches]

* * * * * *

Thou mycht have sene the preparatioun

Maid be the Thre Estaitis of Scotland

In everilk ciete, castell, toure, and town

* * * * * *

Thow saw makand rycht costlie scaffalding

Depaynted weill with gold and asure fyne

* * * * * *

Disagysit folkis, lyke creaturis devyne,

On ilk scaffold to play ane syndrie storie

Bot all in greiting turnit thow that glorie. [greiting = crying: thow = death][46]

Epitaphs in Latin were composed by the French writers Etienne Dolet, Nicolas Desfrenes, Jean Visagier, and an anonymous poet. Gilles Corrozet and Pierre de Ronsard wrote verses in French.[47]

Less than a year after her death, following negotiations completed by David Beaton, James V married the widowed Mary of Guise. She had attended his wedding to Madeleine, and perhaps her uncle, Jean, Cardinal of Lorraine, suggested her to Francis I as a bride for the Scottish king.[48] Twenty years later, listed amongst the treasures in Edinburgh Castle were two little gold cups, an agate basin, a jasper vase, and crystal jug given to Madeleine when she was a child in France.[49]

|

|

|

|

|

The tragic tale of Madeleine of Valois – the ‘Summer Queen of Scots’

7th August 2020

Madeleine of Valois was a French Princess who married James V King of Scots (The Scottish King had the title King of Scots rather than King of Scotland). The marriage was part of the Treaty of Rouen between Scotland and France. As part of that Treaty, James was promised the hand in marriage of a French Princess. Initially, James was contracted to marry another member of the French Royal Family. However, she didn’t appeal to him, and when he arrived at the French court, he wanted only Madeleine and the French King was convinced to allow their marriage to go ahead. Due to Madeleine’s poor health, the marriage would be a short one. She died only six months on from their wedding day. Because of her short time spent as Consort, she received the nickname the ‘Summer Queen of Scots’.

Madeleine was born in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye west of Paris on the 10 August 1520. She was the 5th child of Francis I, King of France and Claude Duchess of Brittany. Her health was fragile, and for that reason, the decision was made to raise her in the Loire Valley where the climate was more warm and temperate. Her mother died when she was three-years-old, and she was raised by her aunt, Marguerite of Navarre, until the remarriage of her father to Eleanor of Austria who accepted Madeleine into her household. By the time she was 16, Madeleine had developed Tuberculosis, the disease which probably took her mother’s life.

Madeleine of Valois Madeleine of Valois

In 1517, three years before Madeleine’s birth, the Treaty of Rouen was signed between France and Scotland. It was a treaty of mutual assistance if the English attacked either country. As part of that Treaty, the French King promised marriage between the Scottish King and one of his daughters. As King James V was only a five year old at the time of the Treaty the negotiations on the marriage did not begin until 1530. Madeleine was then the eldest living daughter. However, King Francis was concerned because of her fragile health she would not survive the harsh Scottish weather and it’s sometimes violent political climate. So he proposed an alternative bride from his extended family Marie of Bourbon who he would regard as a daughter and provide a dowry. In 1536 King James V travelled to France to meet his prospective bride, however on meeting Marie he was not impressed by her. He travelled to the French court, met Madeleine, and the two of them fell in love. They both persuaded King Francis to agree to the marriage which he eventually did. James and Madeleine were married in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on 1 January 1537. King Francis provided a very generous dowry which greatly bolstered the Scottish Treasury.

The wedding was followed by four months of festivities. It felt appropriate due to Madeleine’s health to delay their journey to Scotland until the Spring. They departed France in a fleet of 10 ships and arrived in Leith on 19 May 1537. Madeleine kissed the earth when she arrived in her husband’s kingdom. In preparation for her arrival, James ordered improvements to Falkland Palace and the Chapel Royal. He was also in the process of building new tennis courts and had added a tower built in a French style to Holyrood Palace. A coronation was also planned for Madeleine. However, her health suddenly deteriorated, and she died in the arms of James on 7 July 1537. She was a month short of her 17th birthday. She was buried with great pomp and ceremony in the Royal Chapel of Holyrood Abbey. A year later James married again to Marie of Guise the widowed Duchess of Longueville and a good friend of Madeleine. He would only outlive Madeleine by five years dying in 1542 age 30. Having already lost two infant sons, he left a six day old daughter to succeed to the Scottish throne. Her name would become well known to history, Mary Queen of Scots, but that is another story. James was buried beside his Summer Queen in Holyrood Abbey.

https://royalcentral.co.uk/features/history-blogs/the-tragic-tale-of-madeleine-of-valois-the-summer-queen-of-scots-146769/ |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

36 a 50 de 50

Siguiente Anterior

36 a 50 de 50

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|