|

|

General: STANLEY KUBRICK (2001 A SPACE ODYSEY) BORN IN NEW YORK CITY

Choisir un autre rubrique de messages |

|

|

Stanley Kubrick

|

Stanley Kubrick

|

|

| Born |

July 26, 1928

New York City, U.S.

|

| Died |

March 7, 1999 (aged 70)

|

| Occupations |

- Film director

- producer

- writer

- photographer

|

| Works |

Full list |

| Spouses |

Toba Metz

( m. 1948; div. 1951)

( m. 1955; div. 1957)

|

| Children |

2, including Vivian |

|

Stanley Kubrick (; July 26, 1928 – March 7, 1999) was an American filmmaker and photographer. Widely considered one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, his films were nearly all film adaptations of novels or short stories, spanning a number of genres and gaining recognition for their intense attention to detail, innovative cinematography, extensive set design, and dark humor.

Born in New York City, Kubrick was an average school student but displayed a keen interest in literature, photography, and film from a young age; he began to teach himself film producing and directing after graduating from high school. After working as a photographer for Look magazine in the late 1940s and early 1950s, he began making low-budget short films and made his first major Hollywood film, The Killing, for United Artists in 1956. This was followed by two collaborations with Kirk Douglas: the anti-war film Paths of Glory (1957) and the historical epic film Spartacus (1960).

In 1961, Kubrick left the United States due to concerns about crime in the country, as well as a growing dislike for how Hollywood operated and creative differences with Douglas and the film studios. He settled in England, which he would leave only a handful of times for the rest of his life. In 1978, he made his home at Childwickbury Manor with his wife Christiane, and it became his workplace where he centralized the writing, research, editing, and management of his productions. This permitted him almost complete artistic control over his films, with the rare advantage of financial support from major Hollywood studios. His first productions in England were two films with Peter Sellers: a 1962 film adaptation of Lolita and the Cold War black comedy Dr. Strangelove (1964).

A perfectionist who assumed direct control over most aspects of his filmmaking, Kubrick cultivated an expertise in writing, editing, color grading, promotion, and exhibition. He was famous for the painstaking care taken in researching his films and staging scenes, performed in close coordination with his actors, crew, and other collaborators. He frequently asked for several dozen retakes of the same shot in a film, often confusing and frustrating his actors. Despite the notoriety this provoked, many of Kubrick's films broke new cinematic ground and are now considered landmarks. The scientific realism and innovative special effects in his science fiction epic 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) were a first in cinema history, and the film earned him his only Academy Award (for Best Visual Effects). Filmmaker Steven Spielberg has referred to 2001 as his generation's "big bang" and it is regarded as one of the greatest films ever made.

While many of Kubrick's films were controversial and initially received mixed reviews upon release—particularly the brutal A Clockwork Orange (1971), which Kubrick withdrew from circulation in the UK following a media frenzy—most were nominated for Academy Awards, Golden Globes, or BAFTA Awards, and underwent critical re-evaluations. For the 18th-century period film Barry Lyndon (1975), Kubrick obtained lenses developed by Carl Zeiss for NASA to film scenes by candlelight. With the horror film The Shining (1980), he became one of the first directors to make use of a Steadicam for stabilized and fluid tracking shots, a technology vital to his Vietnam War film Full Metal Jacket (1987). A few days after hosting a screening for his family and the stars of his final film, the erotic drama Eyes Wide Shut (1999), he died at the age of 70.

Early life

High school senior portrait of Kubrick, age 16, c. 1944–1945

Kubrick was born to a Jewish family in the Lying-In Hospital in New York City's Manhattan borough on July 26, 1928.[1] He was the first of two children of Jacob Leonard Kubrick, known as Jack or Jacques, and his wife Sadie Gertrude Kubrick (née Perveler), known as Gert. His sister Barbara Mary Kubrick was born in May 1934. Jack, whose parents and paternal grandparents were of Polish-Jewish and Romanian-Jewish origin,[1] was a homeopathic doctor, graduating from the New York Homeopathic Medical College in 1927, the same year he married Kubrick's mother, who was the child of Austrian-Jewish immigrants.[5] On December 27, 1899, Kubrick's great-grandfather Hersh Kubrick arrived at Ellis Island via Liverpool by ship at the age of 47, leaving behind his wife and two grown children (one of whom was Stanley's grandfather Elias) to start a new life with a younger woman. Elias followed in 1902. At Stanley's birth, the Kubricks lived in the Bronx. His parents married in a Jewish ceremony, but Kubrick was not raised religious and later professed an atheistic view. His father was a physician and, by the standards of the West Bronx, the family was fairly wealthy.

Soon after his sister's birth, Kubrick began schooling in Public School 3 in the Bronx and moved to Public School 90 in June 1938. His IQ was above average but his attendance was poor. He displayed an interest in literature from a young age and began reading Greek and Roman myths and the fables of the Brothers Grimm, which "instilled in him a lifelong affinity with Europe". He spent most Saturdays during the summer watching the New York Yankees and later photographed two boys watching the game in an assignment for Look magazine to emulate his own childhood excitement with baseball. When Kubrick was 12, his father Jack taught him chess. The game remained a lifelong interest of Kubrick's,[12] appearing in many of his films. Kubrick, who later became a member of the United States Chess Federation, explained that chess helped him develop "patience and discipline" in making decisions. When Kubrick was 13, his father bought him a Graflex camera, triggering a fascination with still photography. He befriended a neighbor, Marvin Traub, who shared his passion for photography. Traub had his own darkroom where he and the young Kubrick would spend many hours perusing photographs and watching the chemicals "magically make images on photographic paper". The two indulged in numerous photographic projects for which they roamed the streets looking for interesting subjects to capture and spent time in local cinemas studying films. Freelance photographer Weegee (Arthur Fellig) had a considerable influence on Kubrick's development as a photographer; Kubrick later hired Fellig as the special stills photographer for Dr. Strangelove (1964). As a teenager, Kubrick was also interested in jazz and briefly attempted a career as a drummer.

Kubrick attended William Howard Taft High School from 1941 to 1945.[18] He joined the school's photography club, which permitted him to photograph the school's events in their magazine. He was a mediocre student, with a 67/D+ grade average. Introverted and shy, Kubrick had a low attendance record and often skipped school to watch double-feature films. He graduated in 1945 but his poor grades, combined with the demand for college admissions from soldiers returning from World War II, eliminated any hope of higher education. Later in life Kubrick spoke disdainfully of his education and of American schooling as a whole, maintaining that schools were ineffective in stimulating critical thinking and student interest. His father was disappointed in his son's failure to achieve the excellence in school of which he knew Stanley was fully capable. Jack also encouraged Stanley to read from the family library at home, while permitting Stanley to take up photography as a serious hobby.

Photographic career

Portrait of Kubrick with a camera at the Sadler's Wells Theatre in London, 1949, while a staff photographer for Look

While in high school, Kubrick was chosen as an official school photographer. In the mid-1940s, since he was unable to gain admission to day session classes at colleges, he briefly attended evening classes at the City College of New York, which had open admissions. Eventually, he sold a photographic series to Look magazine,[a] which was printed on June 26, 1945. Kubrick supplemented his income by playing chess "for quarters" in Washington Square Park and various Manhattan chess clubs.

In 1946, he became an apprentice photographer for Look and later a full-time staff photographer. G. Warren Schloat Jr., another new photographer for the magazine at the time, recalled that he thought Kubrick lacked the personality to make it as a director in Hollywood, remarking, "Stanley was a quiet fellow. He didn't say much. He was thin, skinny, and kind of poor—like we all were." Kubrick quickly became known for his story-telling in photographs. His first, published on April 16, 1946, was titled "A Short Story from a Movie Balcony" and staged a fracas between a man and a woman, during which the man is slapped in the face, caught genuinely by surprise. In another assignment, Kubrick took 18 pictures of various people waiting in a dental office. It has been said retrospectively that this project demonstrated an early interest of Kubrick in capturing individuals and their feelings in mundane environments. In 1948, he was sent to Portugal to document a travel piece, and later that year covered the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus in Sarasota, Florida.[b]

Photo of a Chicago streetscape taken by Kubrick for Look magazine, 1949, from State/Lake station

A boxing enthusiast, Kubrick eventually began photographing boxing matches for the magazine. His earliest, "Prizefighter", was published on January 18, 1949, and captured a boxing match and the events leading up to it, featuring American middleweight Walter Cartier. On April 2, 1949, he published photo essay "Chicago-City of Extremes" in Look, which displayed his talent early on for creating atmosphere with imagery. The following year, in July 1950, the magazine published his photo essay, "Working Debutante – Betsy von Furstenberg", which featured a Pablo Picasso portrait of Angel F. de Soto in the background. Kubrick was also assigned to photograph numerous jazz musicians, from Frank Sinatra and Erroll Garner to George Lewis, Eddie Condon, Phil Napoleon, Papa Celestin, Alphonse Picou, Muggsy Spanier, Sharkey Bonano, and others.

Kubrick married his high-school sweetheart Toba Metz on May 28, 1948. They lived together in a small apartment at 36 West 16th Street, off Sixth Avenue just north of Greenwich Village. During this time, Kubrick began frequenting film screenings at the Museum of Modern Art and New York City cinemas. He was inspired by the complex, fluid camerawork of French director Max Ophüls, whose films influenced Kubrick's visual style, and by director Elia Kazan, whom he described as America's "best director" at that time, with his ability of "performing miracles" with his actors. Friends began to notice Kubrick had become obsessed with the art of filmmaking—one friend, David Vaughan, observed that Kubrick would scrutinize the film at the cinema when it went silent, and would go back to reading his paper when people started talking. He spent many hours reading books on film theory and writing notes. He was particularly inspired by Sergei Eisenstein and Arthur Rothstein, the photographic technical director of Look magazine.[c]

|

|

|

Premier

Premier

Précédent

2 à 4 de 4

Suivant

Précédent

2 à 4 de 4

Suivant

Dernier

Dernier

|

|

|

Film career

Short films (1951–1953)

Kubrick shared a love of film with his school friend Alexander Singer, who after graduating from high school had the intention of directing a film version of Homer's Iliad. Through Singer, who worked in the offices of the newsreel production company, The March of Time, Kubrick learned it could cost $40,000 to make a proper short film, a sum he could not afford. He had $1500 in savings and produced a few short documentaries fueled by encouragement from Singer. He began learning all he could about filmmaking on his own, calling film suppliers, laboratories, and equipment rental houses.

Kubrick decided to make a short film documentary about boxer Walter Cartier, whom he had photographed and written about for Look magazine a year earlier. He rented a camera and produced a 16-minute black-and-white documentary, Day of the Fight. Kubrick found the money independently to finance it. He had considered asking Montgomery Clift to narrate it, whom he had met during a photographic session for Look, but settled on CBS news veteran Douglas Edwards. According to Paul Duncan the film was "remarkably accomplished for a first film", and used a backward tracking shot to film a scene in which Cartier and his brother walk towards the camera, a device which later became one of Kubrick's characteristic camera movements. Vincent Cartier, Walter's brother and manager, later reflected on his observations of Kubrick during the filming. He said, "Stanley was a very stoic, impassive but imaginative type person with strong, imaginative thoughts. He commanded respect in a quiet, shy way. Whatever he wanted, you complied, he just captivated you. Anybody who worked with Stanley did just what Stanley wanted".[d] After a score was added by Singer's friend Gerald Fried, Kubrick had spent $3900 in making it, and sold it to RKO-Pathé for $4000, which was the most the company had ever paid for a short film at the time. Kubrick described his first effort at filmmaking as having been valuable since he believed himself to have been forced to do most of the work, and he later declared that the "best education in film is to make one".

Inspired by this early success, Kubrick quit his job at Look and visited professional filmmakers in New York City, asking many detailed questions about the technical aspects of filmmaking. He stated that he was given the confidence during this period to become a filmmaker because of the number of bad films he had seen, remarking, "I don't know a goddamn thing about movies, but I know I can make a better film than that". He began making Flying Padre (1951), a film which documents Reverend Fred Stadtmueller, who travels some 4,000 miles to visit his 11 churches. The film was originally going to be called "Sky Pilot", a pun on the slang term for a priest. During the course of the film, the priest performs a burial service, confronts a boy bullying a girl, and makes an emergency flight to aid a sick mother and baby into an ambulance. Several of the views from and of the plane in Flying Padre are later echoed in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) with the footage of the spacecraft, and a series of close-ups on the faces of people attending the funeral were most likely inspired by Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925) and Ivan the Terrible (1944/1958).

Flying Padre was followed by The Seafarers (1953), Kubrick's first color film, which was shot for the Seafarers International Union in June 1953. It depicted the logistics of a democratic union and focused more on the amenities of seafaring other than the act. For the cafeteria scene in the film, Kubrick chose a dolly shot to establish the life of the seafarer's community; this kind of shot would later become a signature technique. The sequence of Paul Hall, secretary-treasurer of the SIU Atlantic and gulf district, speaking to members of the union echoes scenes from Eisenstein's Strike (1925) and October (1928). Day of the Fight, Flying Padre and The Seafarers constitute Kubrick's only surviving documentary works; some historians believe he made others.

Early feature work (1953–1955)

Duration: 1 hour, 10 minutes and 12 seconds.1:10:12Subtitles available.CCFear and Desire (1953)

After raising $1000 showing his short films to friends and family, Kubrick found the finances to begin making his first feature film, Fear and Desire (1953), originally running with the title The Trap, written by his friend Howard Sackler. Kubrick's uncle, Martin Perveler, a Los Angeles pharmacy owner, invested a further $9000 on condition that he be credited as executive producer of the film. Kubrick assembled several actors and a small crew totaling fourteen people (five actors, five crewmen, and four others to help transport the equipment) and flew to the San Gabriel Mountains in California for a five-week, low-budget shoot. Later renamed The Shape of Fear before finally being named Fear and Desire, it is a fictional allegory about a team of soldiers who survive a plane crash and are caught behind enemy lines in a war. During the course of the film, one of the soldiers becomes infatuated with an attractive girl in the woods and binds her to a tree. This scene and others are noted for their rapid close-ups on the faces of the cast. Kubrick had intended for Fear and Desire to be a silent picture in order to ensure low production costs; the added sounds, effects, and music ultimately brought production costs to around $53,000, exceeding the budget. He was bailed out by producer Richard de Rochemont on the condition that he help in de Rochemont's production of a five-part television series about Abraham Lincoln on location in Hodgenville, Kentucky.

Fear and Desire was a commercial failure, but garnered several positive reviews upon release. Critics such as the reviewer from The New York Times believed that Kubrick's professionalism as a photographer shone through in the picture, and that he "artistically caught glimpses of the grotesque attitudes of death, the wolfishness of hungry men, as well as their bestiality, and in one scene, the wracking effect of lust on a pitifully juvenile soldier and the pinioned girl he is guarding". Columbia University scholar Mark Van Doren was highly impressed by the scenes with the girl bound to the tree, remarking that it would live on as a "beautiful, terrifying and weird" sequence which illustrated Kubrick's immense talent and guaranteed his future success. Kubrick himself later expressed embarrassment with Fear and Desire, and attempted over the years to disown it, keeping prints of the film out of circulation.[e] During the production of the film, Kubrick accidentally almost killed his cast with poisonous gasses.[49]

Following Fear and Desire, Kubrick began working on ideas for a new boxing film. Due to the commercial failure of his first feature, Kubrick avoided asking for further investments, but commenced a film noir script with Howard O. Sackler. Originally under the title Kiss Me, Kill Me, and then The Nymph and the Maniac, Killer's Kiss (1955) is a 67-minute film noir about a young heavyweight boxer's involvement with a woman being abused by her criminal boss. Like Fear and Desire, it was privately funded by Kubrick's family and friends, with some $40,000 put forward from Bronx pharmacist Morris Bousse. Kubrick began shooting footage in Times Square, and frequently explored during the filming process, experimenting with cinematography and considering the use of unconventional angles and imagery. He initially chose to record the sound on location, but encountered difficulties with shadows from the microphone booms, restricting camera movement. His decision to drop the sound in favor of imagery was a costly one; after 12–14 weeks shooting the picture, he spent some seven months and $35,000 working on the sound. Alfred Hitchcock's Blackmail (1929) directly influenced the film with the painting laughing at a character, and Martin Scorsese has, in turn, cited Kubrick's innovative shooting angles and atmospheric shots in Killer's Kiss as an influence on Raging Bull (1980). Actress Irene Kane, the star of Killer's Kiss, observed: "Stanley's a fascinating character. He thinks movies should move, with a minimum of dialogue, and he's all for sex and sadism". Killer's Kiss met with limited commercial success and made very little money in comparison with its production budget of $75,000. Critics have praised the film's camerawork, but its acting and story are generally considered mediocre.[f]

Hollywood success and beyond (1955–1962)

While playing chess in Washington Square, Kubrick met producer James B. Harris, who considered Kubrick "the most intelligent, most creative person I have ever come in contact with." The two formed the Harris-Kubrick Pictures Corporation in 1955. Harris purchased the rights to Lionel White's novel Clean Break for $10,000[g] and Kubrick wrote the script,[58] but at Kubrick's suggestion, they hired film noir novelist Jim Thompson to write the dialog for the film—which became The Killing (1956)—about a meticulously planned racetrack robbery gone wrong. The film starred Sterling Hayden, who had impressed Kubrick with his performance in The Asphalt Jungle (1950).

Kubrick and Harris moved to Los Angeles and signed with the Jaffe Agency to shoot the picture, which became Kubrick's first full-length feature film shot with a professional cast and crew. The Union in Hollywood stated that Kubrick would not be permitted to be both the director and the cinematographer, resulting in the hiring of veteran cinematographer Lucien Ballard. Kubrick agreed to waive his fee for the production, which was shot in 24 days on a budget of $330,000. He clashed with Ballard during the shooting, and on one occasion Kubrick threatened to fire Ballard following a camera dispute, despite being aged only 27 and 20 years Ballard's junior. Hayden recalled Kubrick was "cold and detached. Very mechanical, always confident. I've worked with few directors who are that good".

The Killing failed to secure a proper release across the United States; the film made little money, and was promoted only at the last minute, as a second feature to the Western Bandido! (1956). Several contemporary critics lauded the film, with a reviewer for Time comparing its camerawork to that of Orson Welles. Today, critics generally consider The Killing to be among the best films of Kubrick's early career; its nonlinear narrative and clinical execution also had a major influence on later directors of crime films, including Quentin Tarantino. Dore Schary of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) was highly impressed as well, and offered Kubrick and Harris $75,000 to write, direct, and produce a film, which ultimately became Paths of Glory (1957).[h]

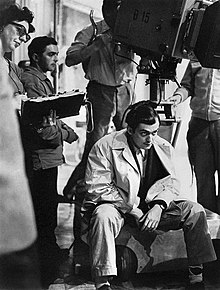

Kubrick during the filming of Paths of Glory in 1957 Kubrick during the filming of Paths of Glory in 1957

Paths of Glory, set during World War I, is based on Humphrey Cobb's 1935 antiwar novel of the same name. Schary was familiar with the novel, but stated that MGM would not finance another war picture, given their backing of the anti-war film The Red Badge of Courage (1951).[i] After Schary was fired by MGM in a major shake-up, Kubrick and Harris managed to interest Kirk Douglas in playing Colonel Dax.[j] Douglas, in turn, signed Harris-Kubrick Pictures to a three-picture co-production deal with his film production company, Bryna Productions, which secured a financing and distribution deal for Paths of Glory and two subsequent films with United Artists.[66][67][68] The film, shot in Munich, from March 1957,[69] follows a French army unit ordered on an impossible mission, and follows with a war trial of three soldiers, arbitrarily chosen, for misconduct. Dax is assigned to defend the men at Court Martial. For the battle scene, Kubrick meticulously lined up six cameras one after the other along the boundary of no-man's land, with each camera capturing a specific field and numbered, and gave each of the hundreds of extras a number for the zone in which they would die. Kubrick operated an Arriflex camera for the battle, zooming in on Douglas. Paths of Glory became Kubrick's first significant commercial success, and established him as an up-and-coming young filmmaker. Critics praised the film's unsentimental, spare, and unvarnished combat scenes and its raw, black-and-white cinematography. Despite the praise, the Christmas release date was criticized, and the subject was controversial in Europe. The film was banned in France until 1974 for its "unflattering" depiction of the French military, and was censored by the Swiss Army until 1970.

|

|

|

|

|

|

In October 1957, after Paths of Glory had its world premiere in Germany, Bryna Productions optioned Canadian church minister-turned-master-safecracker Herbert Emerson Wilsons's autobiography, I Stole $16,000,000, especially for Stanley Kubrick and James B. Harris.[73][74] The picture was to be the second in the co-production deal between Bryna Productions and Harris-Kubrick Pictures, which Kubrick was to write and direct, Harris to co-produce and Douglas to co-produce and star.[73] In November 1957, Gavin Lambert was signed as story editor for I Stole $16,000,000, and with Kubrick, finished a script titled God Fearing Man, but the picture was never filmed.[75]

Marlon Brando contacted Kubrick, asking him to direct a film adaptation of the Charles Neider western novel, The Authentic Death of Hendry Jones, featuring Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid.[k] Brando was impressed, saying "Stanley is unusually perceptive, and delicately attuned to people. He has an adroit intellect, and is a creative thinker—not a repeater, not a fact-gatherer. He digests what he learns and brings to a new project an original point of view and a reserved passion". The two worked on a script for six months, begun by a then unknown Sam Peckinpah. Many disputes broke out over the project, and in the end, Kubrick distanced himself from what would become One-Eyed Jacks (1961).[l]

Kubrick and Tony Curtis on the set of Spartacus in 1960 Kubrick and Tony Curtis on the set of Spartacus in 1960

In February 1959, Kubrick received a phone call from Kirk Douglas asking him to direct Spartacus (1960), based on the historical Spartacus and the Third Servile War. Douglas had acquired the rights to the novel by Howard Fast and blacklisted screenwriter Dalton Trumbo began penning the script. It was produced by Douglas, who also starred as Spartacus, and cast Laurence Olivier as his foe, the Roman general and politician Marcus Licinius Crassus. Douglas hired Kubrick for a reported $150,000 fee to take over direction soon after he fired director Anthony Mann. Kubrick had, at 31, already directed four feature films, and this became his largest by far, with a cast of over 10,000 and a budget of $6 million.[m] At the time, this was the most expensive film ever made in America, and Kubrick became the youngest director in Hollywood history to make an epic. It was the first time that Kubrick filmed using the anamorphic 35 mm horizontal Super Technirama process to achieve ultra-high definition, which allowed him to capture large panoramic scenes, including one with 8,000 trained soldiers from Spain representing the Roman army.[n]

Disputes broke out during the filming of Spartacus. Kubrick complained about not having full creative control over the artistic aspects, insisting on improvising extensively during the production.[o] Kubrick and Douglas were also at odds over the script, with Kubrick angering Douglas when he cut all but two of his lines from the opening 30 minutes. Despite the on-set troubles, Spartacus took $14.6 million at the box office in its first run. The film established Kubrick as a major director, receiving six Academy Award nominations and winning four; it ultimately convinced him that if so much could be made of such a problematic production, he could achieve anything. Spartacus also marked the end of the working relationship between Kubrick and Douglas.[p]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Collaboration with Peter Sellers (1962–1964)

Lolita

Two portrait photographs—both taken by Kubrick—of Sue Lyon, who played the role of Dolores "Lolita" Haze in Lolita

Kubrick and Harris decided to start production of Kubrick's next film Lolita (1962) in England, due to clauses placed on the contract by producers Warner Bros. that gave them complete control over the film, and the fact that the Eady plan permitted producers to write off the costs if 80% of the crew were British. Instead, they signed a $1 million deal with Eliot Hyman's Associated Artists Productions, and a clause which gave them the artistic freedom that they desired. Lolita, Kubrick's first attempt at black comedy, was an adaptation of the novel of the same name by Vladimir Nabokov, the story of a middle-aged college professor becoming infatuated with a 12-year-old girl. Stylistically, Lolita, starring Peter Sellers, James Mason, Shelley Winters, and Sue Lyon, was a transitional film for Kubrick, "marking the turning point from a naturalistic cinema ... to the surrealism of the later films", according to film critic Gene Youngblood.[96] Kubrick was impressed by the range of actor Peter Sellers and gave him one of his first opportunities to improvise wildly during shooting, while filming him with three cameras.[q]

Kubrick shot Lolita over 88 days on a $2 million budget at Elstree Studios, between October 1960 and March 1961. Kubrick often clashed with Shelley Winters, whom he found "very difficult" and demanding, and nearly fired at one point. Because of its provocative story, Lolita was Kubrick's first film to generate controversy; he was ultimately forced to comply with censors and remove much of the erotic element of the relationship between Mason's Humbert and Lyon's Lolita which had been evident in Nabokov's novel. The film was not a major critical or commercial success, earning $3.7 million at the box office on its opening run.[r] Lolita has since become critically acclaimed.[104]

Dr. Strangelove

Kubrick during the production of Dr. Strangelove in 1963

Kubrick's next project was Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), another satirical black comedy. Kubrick became preoccupied with the issue of nuclear war as the Cold War unfolded in the 1950s, and even considered moving to Australia because he feared that New York City might be a likely target for the Russians. He studied over 40 military and political research books on the subject and eventually reached the conclusion that "nobody really knew anything and the whole situation was absurd".

After buying the rights to the novel Red Alert, Kubrick collaborated with its author, Peter George, on the script. It was originally written as a serious political thriller, but Kubrick decided that a "serious treatment" of the subject would not be believable, and thought that some of its most salient points would be fodder for comedy. Kubrick's longtime producer and friend, James B. Harris, thought the film should be serious, and the two parted ways, amicably, over this disagreement—Harris going on to produce and direct the serious cold-war thriller The Bedford Incident.[107][108][109] Kubrick and Red Alert author George then reworked the script as a satire (provisionally titled "The Delicate Balance of Terror") in which the plot of Red Alert was situated as a film-within-a-film made by an alien intelligence, but this idea was also abandoned, and Kubrick decided to make the film as "an outrageous black comedy".[110]

Just before filming began, Kubrick hired noted journalist and satirical author Terry Southern to transform the script into its final form, a black comedy, loaded with sexual innuendo, becoming a film which showed Kubrick's talents as a "unique kind of absurdist" according to the film scholar Abrams. Southern made major contributions to the final script, and was co-credited (above Peter George) in the film's opening titles; his perceived role in the writing later led to a public rift between Kubrick and Peter George, who subsequently complained in a letter to Life magazine that Southern's intense but relatively brief (November 16 to December 28, 1962) involvement with the project was being given undue prominence in the media, while his own role as the author of the film's source novel, and his ten-month stint as the script's co-writer, were being downplayed – a perception Kubrick evidently did little to address.[113]

Kubrick found that Dr. Strangelove, a $2 million production which employed what became the "first important visual effects crew in the world", would be impossible to make in the U.S. for various technical and political reasons, forcing him to move production to England. It was shot in 15 weeks, ending in April 1963, after which Kubrick spent eight months editing it. Peter Sellers again agreed to work with Kubrick, and ended up playing three different roles in the film.[s]

Upon release, the film stirred up much controversy and mixed opinions. The New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther worried that it was a "discredit and even contempt for our whole defense establishment ... the most shattering sick joke I've ever come across", while Robert Brustein of Out of This World in a February 1970 article called it a "juvenalian satire". Kubrick responded to the criticism, stating: "A satirist is someone who has a very skeptical view of human nature, but who still has the optimism to make some sort of a joke out of it. However brutal that joke might be".[118] Today, the film is considered to be one of the sharpest comedy films ever made, and holds a near-perfect 98% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 91 reviews as of November 2020.[119] It was named the 39th-greatest American film and third-greatest American comedy film of all time by the American Film Institute,[120][121] and in 2010, it was named the sixth-best comedy film of all time by The Guardian.[122]

Science fiction (1965–1971)

2001: A Space Odyssey

Kubrick spent five years developing his next film, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), having been highly impressed with science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke's novel Childhood's End, about a superior alien race who assist mankind in eliminating their old selves. After meeting Clarke in New York City in April 1964, Kubrick made the suggestion to work on his 1948 short story "The Sentinel", in which a monolith found on the Moon alerts aliens of mankind. That year, Clarke began writing the novel 2001: A Space Odyssey and collaborated with Kubrick on a screenplay. The film's theme, the birthing of one intelligence by another, is developed in two parallel intersecting stories on two different time scales. One depicts evolutionary transitions between various stages of man, from ape to "star child", as man is reborn into a new existence, each step shepherded by an enigmatic alien intelligence seen only in its artifacts: a series of seemingly indestructible eons-old black monoliths. In space, the enemy is a supercomputer known as HAL who runs the spaceship, a character which novelist Clancy Sigal described as being "far, far more human, more humorous and conceivably decent than anything else that may emerge from this far-seeing enterprise".[t]

Kubrick intensively researched for the film, paying particular attention to accuracy and detail in what the future might look like. He was granted permission by NASA to observe the spacecraft being used in the Ranger 9 mission for accuracy. Filming commenced on December 29, 1965, with the excavation of the monolith on the moon, and footage was shot in Namib Desert in early 1967, with the ape scenes completed later that year. The special effects team continued working until the end of the year to complete the film, taking the cost to $10.5 million. 2001: A Space Odyssey was conceived as a Cinerama spectacle and was photographed in Super Panavision 70, giving the viewer a "dazzling mix of imagination and science" through ground-breaking effects, which earned Kubrick his only personal Oscar, an Academy Award for Visual Effects.[u] Kubrick said of the concept of the film in an interview with Rolling Stone: "On the deepest psychological level, the film's plot symbolized the search for God, and finally postulates what is little less than a scientific definition of God. The film revolves around this metaphysical conception, and the realistic hardware and the documentary feelings about everything were necessary in order to undermine your built-in resistance to the poetical concept".

Upon release in 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey was not an immediate hit among critics, who faulted its lack of dialog, slow pacing, and seemingly impenetrable storyline. The film appeared to defy genre convention, much unlike any science-fiction movie before it, and clearly different from any of Kubrick's earlier works. Kubrick was particularly outraged by a scathing review from Pauline Kael, who called it "the biggest amateur movie of them all", with Kubrick doing "really every dumb thing he ever wanted to do". Despite mixed contemporary critical reviews, 2001 gradually gained popularity and earned $31 million worldwide by the end of 1972.[v] Today, it is widely considered to be one of the greatest and most influential films ever made and is a staple on All Time Top 10 lists.[134][135] Baxter describes the film as "one of the most admired and discussed creations in the history of cinema", and Steven Spielberg has referred to it as "the big bang of his film making generation". For biographer Vincent LoBrutto it "positioned Stanley Kubrick as a pure artist ranked among the masters of cinema". The film marked Kubrick's first use of classical music. Roger Ebert writes: "Although Kubrick originally commissioned an original score from Alex North, he used classical recordings as a temporary track while editing the film, and they worked so well that he kept them. This was a crucial decision. North's score, which is available on a recording, is a good job of film composition, but would have been wrong for 2001 because, like all scores, it attempts to underline the action -- to give us emotional cues. The classical music chosen by Kubrick exists outside the action. It uplifts. It wants to be sublime; it brings a seriousness and transcendence to the visuals", citing Kubrick's use of Johann Strauss II's "The Blue Danube" and Richard Strauss's Also sprach Zarathustra.[139]

A Clockwork Orange

An example of the erotica from A Clockwork Orange (1971)

After completing 2001: A Space Odyssey, Kubrick searched for a project that he could film quickly on a more modest budget. He settled on A Clockwork Orange (1971) at the end of 1969, an exploration of violence and experimental rehabilitation by law enforcement authorities, based around the character of Alex (portrayed by Malcolm McDowell). Kubrick had received a copy of Anthony Burgess's novel of the same name from Terry Southern while they were working on Dr. Strangelove, but had rejected it on the grounds that Nadsat,[w] a street language for young teenagers, was too difficult to comprehend. The decision to make a film about the degeneration of youth reflected contemporary concerns in 1969; the New Hollywood movement was creating a great number of films that depicted the sexuality and rebelliousness of young people. A Clockwork Orange was shot over 1970–1971 on a budget of £2 million. Kubrick abandoned his use of CinemaScope in filming, deciding that the 1.66:1 widescreen format was, in the words of Baxter, an "acceptable compromise between spectacle and intimacy", and favored his "rigorously symmetrical framing", which "increased the beauty of his compositions". The film heavily features "pop erotica" of the period, including a large white plastic set of male genitals, decor which Kubrick had intended to give it a "slightly futuristic" look. McDowell's role in Lindsay Anderson's if.... (1968) was crucial to his casting as Alex,[x] and Kubrick professed that he probably would not have made the film if McDowell had been unavailable. The film marked Kubrick's first collaboration with Wendy Carlos, who provided electronic renditions of Henry Purcell's Music for the Funeral of Queen Mary and Beethoven's "Ode to Joy".[146]

Because of its depiction of teenage violence, A Clockwork Orange became one of the most controversial films of its time, and part of an ongoing debate about violence and its glorification in cinema. It received an X rating, or certificate, in both the UK and US, on its release just before Christmas 1971, though many critics saw much of the violence depicted in the film as satirical, and less violent than Straw Dogs, which had been released a month earlier. Kubrick personally pulled the film from release in the United Kingdom after receiving death threats following a series of copycat crimes based on the film; it was thus completely unavailable legally in the UK until after Kubrick's death, and not re-released until 2000.[y] John Trevelyan, the censor of the film, personally considered A Clockwork Orange to be "perhaps the most brilliant piece of cinematic art I've ever seen," and believed it to present an "intellectual argument rather than a sadistic spectacle" in its depiction of violence, but acknowledged that many would not agree. Negative media hype over the film notwithstanding, A Clockwork Orange received four Academy Award nominations, for Best Picture, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Editing, and was named by the New York Film Critics Circle as the Best Film of 1971. After William Friedkin won Best Director for The French Connection that year, he told the press: "Speaking personally, I think Stanley Kubrick is the best American film-maker of the year. In fact, not just this year, but the best, period."

|

|

|

Premier

Premier

Précédent

2 a 4 de 4

Suivant

Précédent

2 a 4 de 4

Suivant

Dernier

Dernier

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Tous droits réservés | |

|

|