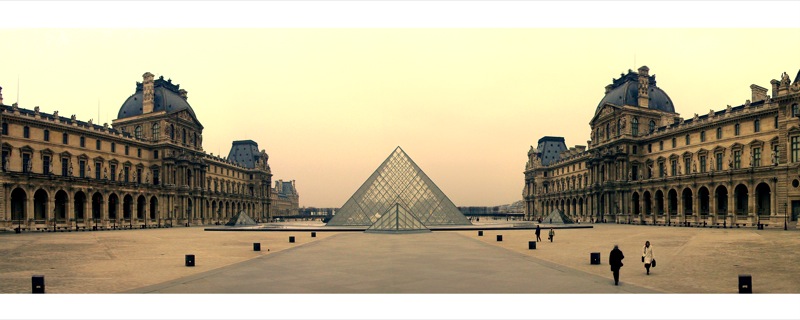

I.M. Pei’s 1989 design for the Pyramide du Louvre at the historic Louvre Palace in Paris France starts with architecture’s most significant symbol: the pyramid. A tunnel descends into structure like the ancient pyramids of Egypt.

The museum spans the entire history of mankind, and so the pyramid itself assumes a futuristic character. Its transparent materials achieve this futurism while opening views to the building surrounding it, and opening natural sunlight into the front lobby. A rather ingenious tension structure is holds the pyramid up.

The La Pyramide Inversée inverted pyramid has been made famous by the Da Vinci Code. But this is just one element of this enormous project, which takes more than a week to properly visit.

Procession To Democracy

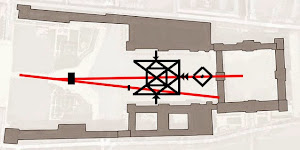

| Pei’s concept sketches show two axis. The first runs through the park to the Arc de Triumph du Carrousel. Here it meets another tilted axis, which continues on into the Louvre. This Axe Historique is the strongest site axis in the world, extending through central Paris to the city’s modern quarter. |  |

| This tilting of spaces at the Arc de Triumph and the pyramid keeps the composition unified yet unexpected.

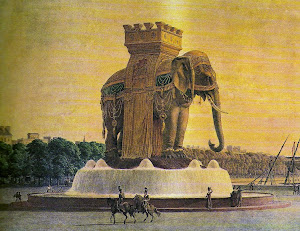

In 1833, a column stood where the pyramid now stands. A third axis tilts slightly as it extends from this point on to the east. This third axis extended to the Place de la Bastillewhere a similar column was constructed in 1835 to commemorate the revolution against King Charles X. The July column at the Place de la Bastille replaced the Elephant of the Bastille, which gives insight into the meaning of the Louvre pyramid. The Elephant was a large structure atop a fountain, which people could enter through a staircase and walk around inside, as with today’s Louvre pyramid. It was cast in bronze from the guns captured by Napoleon in his conquests. In Victor Hugo’s Les Miserable, it housed the homeless children of the Revolution. Run-down and despondant, it symbolized the humility and determination of democracy: |

|

“There it stood in its corner, melancholy, sick, crumbling, surrounded by a rotten palisade, soiled continually by drunken coachmen; cracks meandered athwart its belly, a lath projected from its tail, tall grass flourished between its legs; and, as the level of the place had been rising all around it for a space of thirty years, by that slow and continuous movement which insensibly elevates the soil of large towns, it stood in a hollow, and it looked as though the ground were giving way beneath it. It was unclean, despised, repulsive, and superb, ugly in the eyes of the bourgeois, melancholy in the eyes of the thinker.” -Victor Hugo

The Statue of Liberty in New York is a modern descendant from the Elephant. Visitors walk into and climb a stairway up the Statue, much like in the Elephant. The Louvre Pyramid achieves the same kind of procession, and directly links to its axis in the city. It therefore could assume the symbol of the poor and humble class. The poor gain access to the wealth of the world in the museum. History and art liberates the people.

Astrology

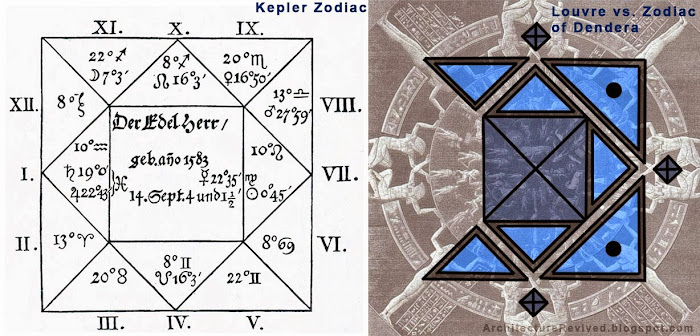

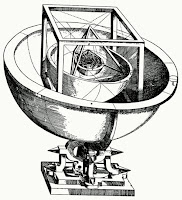

| By 1850, the column in the courtyard was replaced by two circles. Pei’s early sketches start to resemble these two circles. Yet while the inverted pyramid keep a circular outline, the large pyramid is decidedly rectangular. Pei took a square and fit another square inside it. How did Pei get this geometric form? Astronomer Tycho Brahe built the Uraniborg observatory based on the classic chart of the four terrestrial elements. He applied the four states of the four elements (earth, fire, water, air) to the celestial sphere for the first time, asserting a new idea that stars are subject to change like anything else.

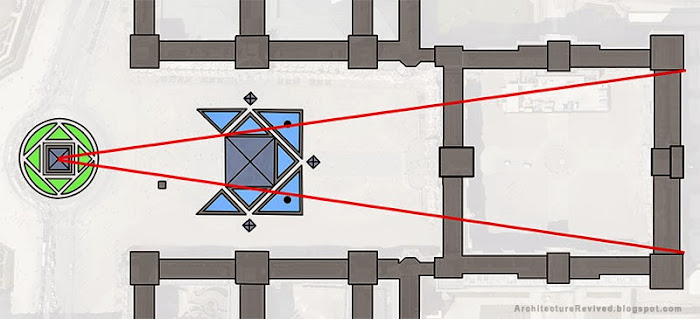

Tycho’s assistant, Johann Kepler applied this building form to astrology. His rectangular horoscope used tilted concentric squares that look very similar to Pei’s form at the Loure. If you lay the classic zodiac over the louvre pyramid, you can see how it fits. Did Pei look at Kepler’s horoscope for the pyramid entrance to the Louvre? Compare the plan-view of the Louvre entrance with Kepler’s zodiac and the ancient astrology diagram: |

|

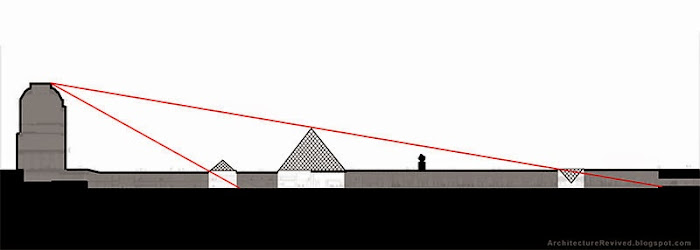

A 90 degree triangle approaches the pyramid from the left side. This T-square aspect pattern forms a trine, which is considered in astrology to be “a source of artistic and creative talent.” This is therefore an appropriate entrance to an art museum. The Louvre’s entrance forms a trine. The 120 degree trine in the musical scale indicates a perfect fifth step, which is the strongest relationship of notes in music. The sun moves almost exactly 120 degrees on the summer solstice in Paris.

| Kepler fit platonic solids inside each other. The tetrahedron was surrounded by the cube. More complex platonic shapes fit inside the tetrahedron, until finally they formed a sphere. This could be the background for Pei’s pyramid inside the Kepler square. The inverse pyramid fits inside a circle and the large pyramid inside a square.

Pei said he used a pyramid because it was “the most structurally stable of forms.”1 The pyramid is glass so that it is only barely seen, an intellectual suggestion. |

|

The large pyramid touches a line between the top of the historic palace and the inverse pyramid. Looking at it in plan view, the edge of the large pyramid touches lines between the ends of the palace and the center of the inverse pyramid. These lines of sight suggest calculus that is used to derive perfect solids. They are an intellectual manifestation of perfect forms.

The pyramid and square could be based on Keppler’s laws of planetary motion. Kepler described the harmony of planets, music, poetry, etc. with proportions. Kepler’s third law, that the period of a planet’s orbit squared is proportional to the distance of the orbit cubed, describes the harmony of motion and distance. The pyramid volume is proportional to a line squared, and the cube volume is proportional to a line cubed.

The inverse pyramid’s proportion to its outer circle is the same as the earth’s proportion to the moon (27%). The large pyramid is likewise exactly 27% the width of the courtyard. The front entrance is half that distance from the front of the courtyard. Both pyramids thus relate the size of the moon to the size of the sun.

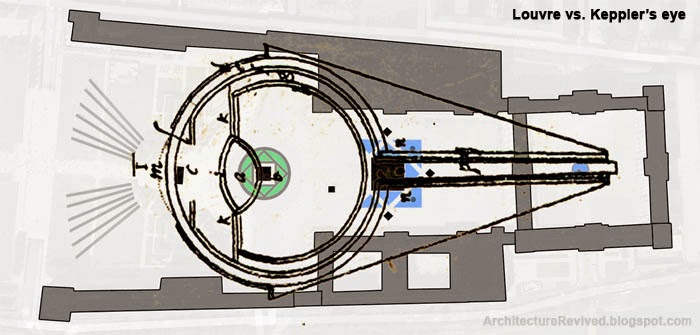

Kepler applied the mathematics of the perfect platonic solids to the epicycles of planets. Rejecting Ptolemic astronomy, Kepler declared that the earth revolves around the sun, and that the moon revolves around the earth, in elliptical orbits. He related these proportions to various things, such as the structure of the human eye. Indeed, if you overlay Kepler’s drawing of the eyeball over the Louvre, you see that the proportions line up. The Arc de Triumph aligns with the front of the cornea, the inverse pyramid with the lens, and the large pyramid with the front of the optic nerve. The hedges in the park even look like light rays approaching the eye from the left. This is because the harmonic proportions of the Louvre universally describe naturally occurring systems.

Golden Mean

The pyramid proportionally relates a system of objects, so it is no surprise that the golden mean is a basis for the pyramid’s size. The golden mean determines form and distance. The golden mean determines the pyramid’s size between the front and back, and the left and right of the courtyard. The statue of King Louis XIV, which is the endpoint of the park axis, aligns with this proportion. The golden mean also relates the inverse pyramid to the fountain edge.

The Louvre pyramid has the same slope as the Great Pyramid in Giza, at 51 degrees. The significance of the golden proportion in the Great Pyramid thus applies to the Louvre. It uses the golden proportion to achieve its form. The procession into the front, descending down into underground also follows the Great Pyramid in Giza.

The summer solstice sun crosses just inside the Arc de Triumph along the Axe Historique as it sets. The sun therefore is of vital importance in this site axis. The setting summer sun establishes a line of site between the statue of King Louis XIV with the inverse pyramid:

Gender

The circle is traditionally female and the square male. The inverse pyramid thus appears female while the larger upright pyramid is male. Many are aware that the Louvre is a metaphor for the chalice and blade. The chalice is the female aspect of creating life and is represented by an inverse pyramid. The blade is the male aspect of death and is represented by an upright pyramid. This metaphor is strengthened when you consider that the inverse pyramid is surrounding by living grass and the upright pyramid by fluid water. The Egyptians believed the waters of chaos must be crossed in the afterlife, and this is why they placed their funeral upright pyramids near the river Nile. Male/female relate to life/death and circle/square.

The entrance procession continues this gender language of circles and squares. The left spiral staircaseswirls in a circular motion, and on the right side a linear staircase descends in strict right angles. The Louvre’s free-standing staircase is a structural marvel, and its unrestrained circular motion was not easily achieved.

I think this gender symbolism is the most significant thing about the Louvre pyramid. Modernism seems intent on destroying all gender in our architectural language, yet here is a stark example of Modernism pushing ancient gender language. Its subtle power is the stuff of mystery novels, yet it is not really understood.

(rvr– flickr/creative commons license)

Life and death are investigated as the pyramid plays with the idea of above-ground and underground. The water fountains reflect the blue sky on the ground and suggests an inverse relationship. The clear pyramid allows light to fill the subterranean space. Then, at the inverse pyramid, everything flips upside down. The blue fountains take the form of blue sky and the transparent pyramid fills into the building. Rather than the building against a sky, it is the sky against the building. It touches a solid form, a small pyramid, a polar opposite to the unsubstantial sky. The roof of the Louvre palace can barely be seen from the inverse pyramid, a visual connection that brings this dichotomy all together.

This forces the visitor to investigate nature’s opposites. From Keppler’s investigation of natural systems, to perfect proportions, and natural opposite relationships, the Louvre makes the museum visitor investigate natural law.

Massimiliano Fuksas borrowed Pei’s concept of glazed sky intruding into building space. His MyZeil mall in Frankfurt swirls glazing around the public space.

(tetraconz– flickr/creative commons license)

(Ivo Jansch– flickr/creative commons license)

(dynamosquito– flickr/creative commons license)

(Carlton Browne– flickr/creative commons license)

(mariosp– flickr/creative commons license)

(mariosp– flickr/creative commons license)

(Guerretto– flickr/creative commons license)

(roryrory– flickr/creative commons license)

(genericface– flickr/creative commons license)