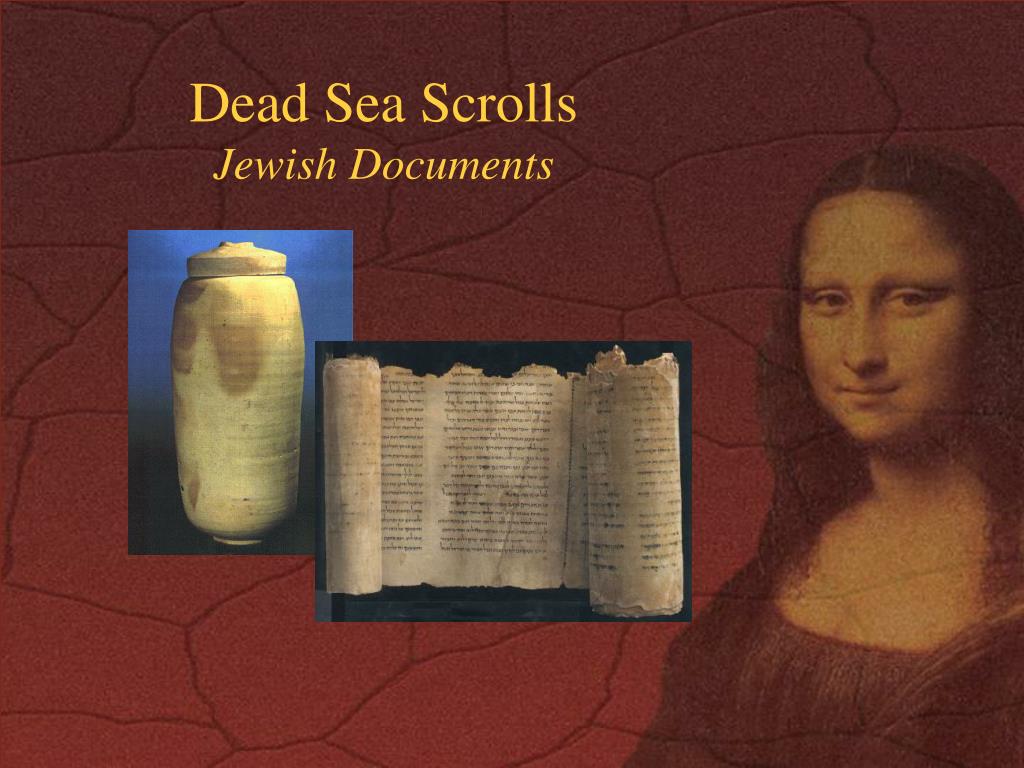

In the year 2000, Australia played host to the Dead Sea Scrolls, arguably the most precious archaeological discovery in Western civilisation, now celebrating seventy-five years. First found in 1946-47 in caves on the western shore of the Dead Sea, scrolls of parchment containing almost all the books of the Hebrew scriptures predated by one thousand years the oldest extant manuscripts, such as the tenth-century Aleppo Codex and the Leningrad Codex. Excavations of the eleven caves around Qumran, where a settlement was uncovered, have continued to yield new fragments, as recently as 2021, adding to the more than 900 manuscripts and 100,000 fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

That the Art Gallery of New South Wales, under the directorship of Edmund Capon, chose the Dead Sea Scrolls to herald the new millennium, in a superb and extensive exhibition involving the Israel Antiquities Authority and an array of international scholars, was a recognition of the foundational importance of the biblical tradition to Australians. I was involved in public events with international Dead Sea Scrolls scholars, such as Laurence Schiffman, George Brooke and Philip Davies, and drawing on my MA and PhD studies at McMaster University, Canada, I co-produced and presented two one-hour documentaries featuring the leading international Dead Sea Scrolls scholars on the religious and scholarly significance of the Scrolls for ABC television’s Compass program.

This essay appears in a recent Quadrant.

Subscribers had no need to wait for the paywall to come down

Important as the Scrolls are for Christians and Jews, for whom the discovery gave unprecedented confirmation of their bedrock tradition, which shaped Western civilisation, the public interest in the Dead Sea Scrolls was especially aroused by the original writings of a radical community, the Yahad (“unity”), which supposedly dwelled at Qumran, on the north-western plateau of the Dead Sea, the archaeological site closest to the caves.[1] The Community Rule, outlining the Yahad’s practices, and the Scroll of the War of the Sons of Light Against the Sons of Darkness (also known as the War Scroll), as well as the Habakkuk Commentary, reflect a sectarian outlook that set itself apart from and in opposition to the rabbis and priests of the Jewish tradition. They looked forward to an imminent final showdown in the “End of Days” when only the Yahad would emerge triumphant.

With the carbon dating of the Scrolls establishing a window from approximately the third century BC to first century AD, the question on everyone’s mind was “Could this sectarian group be the origins of the Jesus movement?” After all, the urgency of the coming Kingdom of God (or Kingdom of Heaven) was a key message of Jesus in the three synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke. Yet it is also true that the Roman presence in Judea with its brutal suppression of peasant anti-taxation revolts (in 6 AD) and its desecration and plundering of the Jerusalem Temple coffers, caused a great deal of social unrest, apocalyptic writing and messianic fervour. Politically, these culminated in the Great Revolt of 66–73 AD, the Kitos rebellion in 115 (fought largely outside Judea) and the Bar Kochba (“Son of the Star”) war from 132 to 136 AD.

Jesus was executed long before these major Jewish wars against the Romans were mounted and failed, but his legacy would be forever associated with the reverse strategy, to avoid war with the enemy: “Render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s” (Matthew 20:21, Mark 12:17; Luke 20:25).

This proverbial saying has become a symbol of compromise, and even pacifism, but its actual meaning remains ambiguous: is Jesus comparing the temple taxes, which were paid in Jewish shekels that were decorated with animal and vegetable motifs and never human representations, to the imperial taxes, which were paid with Roman coins that bore images of Caesar? Or was Jesus waxing more profound on the limited temporal authority of Caesar compared to the eternal authority of God? Sean Freyne, a scholar of early Christianity, suggests the conundrum remains unanswered.[2]

What is clear, however, is that God and Caesar, or religion and politics, turn on the question of authority, and Jesus’s deft handling of them suggests that they should be kept apart as two distinct realms. It is a position consistent with the classic Jewish view, which had become seriously eroded in Jesus’s time by the Hellenistic Jewish priests of the Temple. In stark contrast to a modus vivendi approach to the turbulent politics of the day, the community at Qumran possessed the War Scroll, which anticipates a cosmic battle between itself, the Sons of Light, under the protection of angels, against everyone else, the Sons of Darkness, led by the evil influence of Belial (the devil).

The extreme position of the Qumran community prompted many scholars to identify it with the Essenes, a Jewish sect among several that were described by the first-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus in Jewish War, in Jewish Antiquities and in Life, and also by the Jewish philosopher Philo Judeaus a half-century earlier, as well as Pliny the Elder. Although the term Essene never appears in the texts, and some scholars rejected the connection on various grounds, including that Josephus described the Essenes as an urban sect found in many towns, the Yahad’s Community Rule, also known as the Manual of Discipline, nonetheless had many similarities with the Essenes, including its exclusively male membership, celibacy, strict purity laws, a focus on healing and property in common.[3] All these characteristics suggested a link with Jesus and his disciples.

Much ink has been spilt on the possible association between Jesus, the Essenes and Qumran, but most serious scholars conclude nothing more substantive than the fact that the Essenes and the Qumran community were among the many Jewish sects, schools of thought, and priestly lineages (Zadokite in respect to Qumran) that vied for legitimacy during Jesus’s lifetime. Whether Jesus was personally a member of the Qumran community has been largely dismissed as unfounded.

But far-fetched speculations are among the most tenacious in the popular mind, because they rely on persuasive arguments that catch the spirit of the times. Such was the case with the publication of Jesus the Man: New Interpretations from the Dead Sea Scrolls (1992), by the Australian scholar Barbara Thiering.

Using the pesher technique of interpretation in Dead Sea Scrolls documents, which alleges that there is a plain meaning and a hidden meaning in scripture, Thiering believed that the New Testament contained a secret biography of Jesus. Having “cracked the code”, she revealed that Jesus was born out of wedlock among the Essenes in Qumran, was crucified there alongside Judas Iscariot and Simon Magus, was revived by snake venom (the Essenes were keen practitioners of medical concoctions), escaped and married Mary Magdalene and later Lydia of Philippi, and died in Rome in obscurity. Today, it would qualify as a Netflix series.

While Jesus the Man received a consistently negative response by scholars, what was not in doubt was how readily the Dead Sea Scrolls became subject to outlandish theories that reflected the current zeitgeist. Thiering, who received her PhD from the University of Sydney and lectured on the “pesher technique” in the late 1980s and early 1990s, reflected the then popular feminist theories about Jesus’s female companions, especially Mary Magdalene to whom he first appeared after his crucifixion. Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code and Angels and Demons turned these theories into full-blown conspiracy best-sellers.

Thiering’s was not the first nor the most daring use of the Dead Sea Scrolls to overturn the received view of Christianity. She was influenced by the eccentric work of John Allegro, a lecturer in Comparative Semitic Philology at the University of Manchester, who was the first to translate the unique Copper Scroll in the mid-1950s. Allegro, who was invited into the original inner circle of translators due to his specialisation in Hebrew dialects, popularised the Dead Sea Scrolls in his BBC radio broadcasts, in which he put forth the idea that the leader of the Qumran Community, known as the Teacher of Righteousness, had been crucified. His Discoveries in the Judean Desert of Jordan in 1968 was severely criticised by most of the scholars working on the Scrolls, and this tendency would be magnified when he published The Sacred Mushroom and the Cross (1970) and The Dead Sea Scrolls and Christian Myth (1979).

The popular drug culture of the 1970s had come full circle in Allegro’s works in which he claimed that Christianity was none other than a shamanistic fertility cult that emerged within the Essenes, who used psychedelic mushrooms in their rituals. Jesus, according to Allegro, did not exist, but was a code word for Aminita muscaria, the mushroom which is the basis of LSD.

No wonder his works were hugely popular among a generation keen to remake Christianity into their own image. (It was reminiscent of the rising interest in indigenous shamanism and the ingesting of “magic mushrooms”, popularised in the 1968 best-seller by Carlos Castaneda, The Teachings of Don Juan, which falsely claimed to be an academic work, and is now accepted as a work of fiction.)

The Dead Sea Scrolls became a magnet for those, like Edmund Wilson, with an axe to grind, most specifically as confirmation of the “end of Christianity”. Fortunately, the Dead Sea Scrolls community of scholars today is by and large extremely cautious in their conclusions and respectful of the historical consensus based on painstaking research of ancient texts in several languages, including classical Hebrew, Aramaic, Nabatean and Greek. More than most scholars of early Christianity and rabbinic Judaism, they know how richly complex was the period in which their respective traditions took shape, together and in opposition, influenced by and reacting to a host of ideas circulating among the radical movements and sects which did not ultimately survive. Neither did the eccentric theories of Allegro and Thiering.

Rachael Kohn is a broadcaster and writer on religion and spirituality.

[1] Some scholars, notably Norman Golb (d 2021), at the University of Chicago Divinity School, whom I interviewed, argued against that the Scrolls were a library, assembled from libraries in Jerusalem including the Temple, for safe keeping.

[2] Sean Freyne, The Jesus Movement and Its Expansion: Meaning and Mission (Grand Rapids Mich: Wm B Eerdmans Publishing) 2014: 60.

[3] Leading Scrolls scholar and first to provide a full English translation of the them, Geza Vermes argues in favour of the Essene connection, An Introduction to the Complete Dead Sea Scrolls, London: SCM Press, 1977:126.