DID THE TEMPLARS REALLY GO OUT OF EXISTENCE?

The history of Switzerland is, at best, elusive. It is that way seemingly on purpose, with its origins murky. Its origin as a confederacy, we are told, originated with a man named William Tell who supplied the spark for independence. Yet most scholars say his story is a myth. The Swiss have their own version of a Declaration of Independence. It was said to be lost but was actually hidden for centuries. There is a reason the story of the origins of Switzerland as a country has been kept secret. It has everything to do with the Knights Templar resurrection.

On May 18, 1291, the last stronghold of the Templars in the Holy Lands fell to Al-ashraf Khalil. This was the fortress at Acre. The entire reason for the existence of the Templars was lost in that last battle. Instead of a fighting force defending the Holy Lands from Islamic control, the Knights Templar were now just a bloated business. The proverbial writing was on the wall.

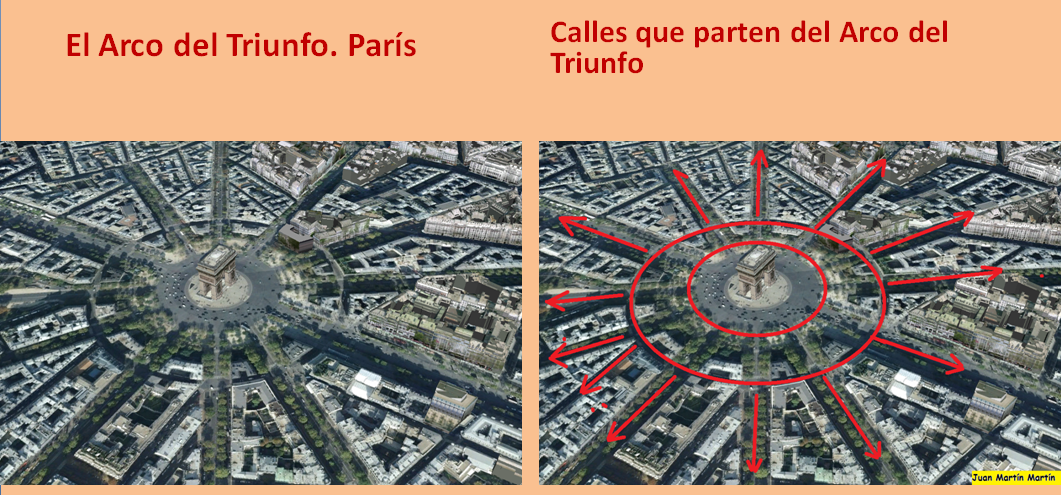

With no sacred mission, the Templars were now simply a corporation free from taxes and answering to no one. They succeeded only in incurring the wrath of everyone with whom they dealt. Many ports, objecting to the monopoly of Templar fleets, refused their ships. Their vast banking system, stretching from London to Jerusalem, held the jewels of the royals and the promissory notes of kings. Having introduced the concept of branch banking, this institution would be the world’s first international bank. The order, the beneficiary of so much land from so many donors, paid no property taxes. Their “haughtiness” annoyed their neighbors who did pay taxes on their own properties. It had a competitive advantage in any business that it pursued. The greatest mistake the Templars made, however, was to refuse the French king as a member and to believe they had him under their thumb. King Phillip owed the order a great sum of money, and his inability to tax Templar properties forced him to raise taxes on the populace. He often had to flee his own people and at least once the mob chased him into the Paris Temple. The Templars, however, were not his friend. The king decided if you can’t join them, beat them. He enlisted the Pope by claiming they were heretics.

Having made enemies of the Pope and King Philip IV, the Templars had the French army to contend with, but even so they had much going for them. As the largest intelligence operation in the world, they were tipped off that the French King was planning to arrest the Templars and steal their wealth. They also had an exit strategy. This became obvious years later when Templar treasure was loaded on their fleet before it sailed from La Rochelle to Scotland, and when their cavalry units simply moved to Spain and Portugal where they were restructured as “new” orders including the Knights of Santiago and the Knights of Christ, still flying the same Templar flag. Columbus had married into a Knights of Christ family and continued to fly the Templar flag nearly 200 years after their perceived demise. In all, eighty percent of the Templars avoided arrest when King Phillip went on the attack.

Even before that, though, the Templar’s exit strategy called for an independent country of their own making. On August 1, 1291, ten weeks after Acre fell, three, small regions of the future Switzerland signed a unification pact. These were the cantons of Uri, Schwyz, and Unterwalden. It would be Schwyz that would later give its name to the country of Switzerland.

The flag of the Swiss canton of Schwyz that gave its name to the country is basically an inversion of the Templar flag. It is a white cross on a red field. This was a smaller cross than the Templar cross, but when the country united, it became a large white cross on a red field. Much later, battle flags would have a red field with a white cross. Within the white cross was a sword. Other symbols and emblems, such as keys and lambs, were used by the Templars and are incorporated into the flags of Switzerland.

Before 1291, the future country was not at all unified. Switzerland had no shared religion, no shared language, or even a common dynasty. In Roman times they were considered part of the Roman Empire and somewhat Christian, but Germanic hordes from the north brought pagan religion and Germanic language.

As Rome imploded, the territory that would become Switzerland was under a handful of minor family dynasties that mostly came apart. Circa 1300, no one expected the small towns and thinly settled valleys to unite or form cantons or states. The Holy Roman Empire decided these were its property but asked only for taxes. Modern historians concur there was no such thing as Swiss, or Switzerland, before 1400.

Birth of the Templar Nation

That changed in 1291 when a document known as the Bundesbrief united Uri Schwyz and Unterwalden. Representatives would convene at a mountain meadow on Lake Lucerne. The forest cantons, as they were known, would sign a compact of mutual assistance. Folktales record the white-coated, red-crossed knights that pledged assistance to the Swiss Confederacy as it would be known. The document itself was like the American Declaration of Independence, and while it might be expected to have been regarded as sacred; it wasn’t. Instead it was simply lost until the nineteenth century. Or at least kept secret. Then when the expected assault on the Templar existence finally came the Templars were ready.

On Oct 13, 1307, the command went out to arrest the Knights Templar. That day and in the weeks to follow, 600 out of 3000 knights in France were arrested. These were just knights. Each had a retinue of squires, servants, and aides who were not arrested. So, the Templar organization still had thousands who were not apprehended. Some had been traveling regularly through the Alps to Switzerland, which had once been a province of the Merovingian kings and where the small city of Sion once held the Merovingian mint.

Swiss Alpine passes and its central location brought trade through the country and allowed craftsmen access to markets outside of their country. Trade fairs and markets from these times always had compliant bankers and moneylenders who would assist merchants. Similarities between the Templar invention of international banking and Switzerland’s leading role in banking today are no coincidence.

Just how many Templar knights entered Switzerland would not be known. The Hapsburg family “controlled” Swiss cantons and did not allow anyone to challenge their ability to tax the cantons. They allowed the cantons to rule themselves in law and custom as long as they paid their taxes. The Templars, however, had existed for nearly 200 years without paying taxes. Unfortunately, the Swiss, noted for their secrecy, either know little of their early history or deliberately claim not to know.

William Tell and Swiss Independence

The story of William Tell may be a cover tale for the new challenge to the Hapsburg establishment. It is said to be a myth, but unlike myths that begin with nebulous timeframes, the William Tell story begins with an exact date. On November 18, 1307, William Tell visited the town of Altdorf with his son. This was five weeks after the Templars fled France ahead of their arrests. Altdorf was a municipality of Uri, one of the first three cantons to unite shortly after the Templar loss of Acre. He met with and offended Albrecht Gessler, who is the “Vogt,” a nominal bureaucrat appointed by the Habsburgs. The Vogt had hung his hat in the center of town and declared everyone who passed the hat had to bow to it. Tell passed by and publicly refused to bow. Gessler wanted to arrest the stranger but instead challenged him to shoot an apple off his son’s head with an arrow. Tell accomplished the dangerous challenge and Gessler commented that he still held another arrow. Tell’s answer was that it was for killing Gessler if he missed. The outcome was that Tell killed Gessler. His arrow struck a blow for liberty igniting the cantons against their Hapsburg overlords. Tell played a leading role in the rebellion that followed. In 1307–1308 many forts of the Hapsburgs were destroyed and this, in effect, united others and finally brought about the Swiss Confederation. Tell himself was declared the “first confederate” in a song of his exploits.

The Scots Guard and the Swiss Guard

Possibly the largest contingent of fleeing Templars went into the welcoming arms of Scotland. In Scotland, Robert Bruce had challenged the power of the King of England and declared Scotland’s independence. The English army would ride north and meet the Scots at Bannockburn. Just as it appeared the Scots were beaten, a fresh force of Templar Knights rode into battle and turned the tide. It was June 24, 1314, the feast of St. John Baptist, a most sacred day to the Templars. Soon afterwards the Scots Guard became a military force for hire.

In Switzerland, the Swiss cantons decided not to pay the feudal taxes imposed on them. The Hapsburg dukes were not simply going away though. In 1315, just one year after Bannockburn, the dukes sent an army to enforce the feudal dues. As with the English invasion of Scotland, the Hapsburgs thought the tiny cantons had no chance of resisting their army. But, like the English at Bannockburn, the Hapsburgs were not ready for the army they faced. In the Pass of Morgarten, the infantry of Uri and Schwyz defeated the Austrian cavalry in what became known as “the Marathon of Switzerland.” Like the Scottish victory at Bannockburn, the Swiss fought and defeated a larger enemy. No doubt incorporating ex-Templars as well as their training and support, the Swiss would form the Swiss Guard. It was also a mercenary force that could be leased out only with the approval of the Guard, not by the whims of a king. Ironically the Swiss Guard would be hired to defend the Vatican.

The Pontifical Swiss Guard had their origins in the fifteenth century when Pope Sixtus IV made an alliance with the Swiss Confederation. History shows their independence in not always fighting for one country. They fought for France against Naples, and both for and against the Holy Roman Empire. Their bravery, however, was never in question. Like the Templars, they never fled from greater odds. On May 6, 1527, 189 Swiss Guards fought a rear-guard action against the Holy Roman Empire. While 40 guard members helped Pope Clement VII escape, 147 of the 189 died, including their commander.

The Swiss Confederation grew with the addition of Zurich, Bern, Lucerne and Zug. While it had a strong fighting force, it declared its neutrality. It would take another two centuries to complete the formation of what became Switzerland. By becoming a neutral nation they were possibly protecting themselves from the Catholic France and Catholic Austria to the west and east. They were not always neutral, however, and had taken Lugano and other Italian properties while Italy was still a disrupted state. Oddly enough, in a very Protestant country, the Swiss Guard is made up of Swiss male citizens who are trained in the Swiss military and practice the Catholic religion.

It is no coincidence that the modern Red Cross also was born in Switzerland. The battle of Solferino was fought on June 24 of 1857. Like Bannockburn this was the Feast of St. John the Baptist. The story goes that a young man by the name of Henri Jean Dunant came to survey the damage. He later produced a book on the battlefield and presented it to wealthy and prominent citizens to create an international organization of relief workers. Switzerland at this time was a Confederation of 22 cantons and 3000 communes. Its neutrality was reiterated and protected by the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648 and confirmed by the Treaty of Vienna in 1815. Five of the prominent men met and agreed to call for a larger meeting. Prince Heinrich XIII of Reuss represented the Order of St. John of Jerusalem and became Vice President. Impressed by the St. John connection, delegates came from around the world. The HQ was at Basle. Rooms were taken in a chapel owned by the Teutonic knights.

The Country the Templars Created

Modern Switzerland has been built on banking, bank secrecy, precision engineering and pharmaceuticals. Finance is the central pillar of the Swiss economy. While bank secrecy is on the defense from the prying IRS, over five trillion dollars of “cross-border” wealth is known to be managed in Switzerland. Like the Templar bank of centuries before, the banks of Switzerland cater to national rulers, who often treat their nation’s riches as their own. The Swiss banks in turn have been accused of treating the money deposited as belonging to them. When President Mobutu of Zaire died in exile in 1997, Swiss newspapers reported he had $5 billion deposited in their banks. Swiss banks returned $8 million.

Templar scientific studies, once dubbed alchemy, are mirrored in the dominance of Swiss chemical and pharmaceutical companies. BASF, Zeochem, Novartis, and Hoffman-L Roche are Swiss companies with an international customer base.

Finally, the Templars and their sister order of St. Bernard the Cistercians, were known for their engineering abilities. Today the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator sits inside the Swiss border with France. This is CERN. Most Americans heard of it only through Dan Brown’s Angels & Demons when his character Robert Langdon discovers CERN technology is going to be used to destroy the Vatican. (Other conspiracy theorists worry CERN could destroy the planet.) It should be noted it was a CERN scientist, not Al Gore, who invented the World Wide Web in 1989.

The Templar order that the French King and the Pope forced into hiding, remains alive, and hiding in plain sight, in Switzerland, the center of Europe.

![Secrets Of The PINEAL GLANDTHIRD EYE The Gateway To God [ HD, 1280x 720] : Free Download, Borrow, and Streaming : Internet Archive](https://archive.org/download/secrets-of-the-pineal-glandthird-eye-the-gateway-to-god-hd-1280x-720/secrets-of-the-pineal-glandthird-eye-the-gateway-to-god-hd-1280x-720.thumbs/Secrets%20of%20the%20PINEAL%20GLANDTHIRD%20EYE%20the%20gateway%20to%20God%20[HD,%201280x720]_000054.jpg)