Desde muy antiguo, el hombre ha querido poner límites geográficos a la Tierra y ha evidenciado una innegable necesidad de introducir magnitudes de medición que permitan a cartógrafos, geógrafos e, incluso, astrónomos tener una posibilidad de situar un punto con exactitud en nuestro planeta.

Hasta 1884, momento en que se celebró la Conferencia Internacional del Meridiano, eran varios los puntos de partida utilizados para medir la tierra hacia derecha e izquierda. En este momento se tomó como medida universal el Meridiano de Greenwich, el meridiano cero, el punto desde el que se habrían de medir todas las distancias en la tierra en el sentido este-oeste. Pero este meridiano no fue el primero ni el único que existió en nuestro planeta.

Medallón Arago situado entre el 152 y el 154 del Boulevard Saint Germain .

Uno de los más conocidos hasta entonces fue, precisamente, el Meridiano de París, una línea imaginaria cuyo punto cero pasaba por el Observatorio Astronómico de la ciudad.

Hoy nos vamos a referir a esta línea imaginaria que, con el paso del tiempo y a modo de homenaje, ha tenido su réplica sobre el pavimento de París. Más aún después de que Dan Brown publicara su célebre obra «El Código da Vinci» en el que se le menciona en varias ocasiones identificándola (erróneamente) con la Línea Rosa.

Hablemos del autor de este meridiano de París.

François Arago, quien dio nombre a esta línea imaginaria, fue un astrónomo francés que nació en 1786 muy cerca de Perpignan y su familia era catalanoparlante. Su padre era un campesino acomodado que pudo dar carrera universitaria a varios de sus ocho hijos. Estudió en el instituto público de Perpignan. Mostrando gustos militares desde su infancia, se centró en el estudio de las matemáticas para preparar el concurso de ingreso en la Escuela Politécnica de París.

Medallón Arago situado en los Jardines de Luxemburgo.

En dos años y medio consiguió el nivel adecuado en todas las ciencias exigidas para el concurso de ingreso en la escuela. Fue admitido con la nota más alta de su promoción y se matriculó en la sección de artillería, pero se quejaba del nivel insuficiente de los profesores. Criado en un ambiente republicano, se negó (junto con otros alumnos) a felicitar a Napoleón con motivo de su coronación en 1804, desobedeciendo las normas de esta Gran Escuela.

En el año 1804, gracias a la recomendación de Siméon Poisson y Pierre Simon Laplace, recibió el cargo de secretario-bibliotecario del Bureau des Longitudes (Oficina de las Longitudes) del Observatorio de París mientras seguía estudiando en la Escuela Politécnica. De esta forma consiguió ser incluido junto con Pierre-Simon Laplace y Jean Baptiste Biot en el grupo llamado a completar las medidas del meridiano que empezó años antes J. B. J. Delambre.

Ahí empezó su andadura en busca del meridiano exacto, un meridiano que pasaba por París.

Arago tuvo la suerte de preservar todos los resultados de sus investigaciones y los depositó en el Bureau des Longitudes de París. La calidad de sus trabajos le convierten enseguida en un ciéntifico renombrado no sólo en el seno de la comunidad científica sino también en la opinión pública.

Medallón Arago situado en el Palais Royal.

En 1830 Arago, que siempre había profesado ideas republicanas, fue elegido diputado por los Pirineos Orientales y mantendrá su escaño durante toda la monarquía de julio. A ello dedicó todos sus recursos oratorios y científicos centrándose en la cuestión de la educación pública, la mejora de las condiciones de vida de los obreros, el sufragio universal, los premios a los inventores y el apoyo a las ciencias. Después de los acontecimientos de febrero de 1848 que provocaron la caída del Rey Louis Philippe I, Arago es nombrado miembro del gobierno provisional como Ministro de la Guerra, la Marina y las Colonias, y proclamó la República ante el pueblo de París.

Regresó a su puesto en el Observatorio donde prosiguió con su incansable labor científica. Casi no volvió a pisar la Asamblea, a pesar de ser reelegido diputado en 1849.

Tras el golpe de Estado de Luís Napoleón en diciembre de 1852, Arago intentó movilizar a la Academia sin éxito. Obligado como funcionario a prestar juramento al Emperador, se negó y dimitió, pero Napoleón le aseguró que no sería inquietado.

Afectado de diabetes y de problemas intestinales, falleció al año siguiente en París. Fue enterrado en el cementerio de Père-Lachaise.

Medallón Arago situado en el Cour Napoleon del Louvre.

De la importancia de este personaje han quedado evidencias en París.

Hay un boulevard dedicado con su nombre que linda con el edificio del Observatorio Astronómico de París.

Arago también es uno de los 72 científicos cuyo nombre Eiffel mandó grabar en las cuatro caras de la torre que levantó.

Pero en París también hay un monumento con el que se le recuerda, un monumento imaginario que mide 9 kilómetros de largo y que es difícil de apreciar: la célebre línea Arago.

Esta es la historia. En 1893 se decide erigir una estatua de bronce con la efigie del astrónomo junto al Observatorio de París, sin embargo, en 1942, debido a las necesidades de construir cañones para la II Guerra Mundial, el gobierno francés la funde y desaparece.

Cuarenta y dos años más tarde, en 1994, el gobierno de la ciudad decide restablecer el honor a Arago y pide al artista holandés Jan Dibbets su construcción. Este artista, inspirándose en el célebre Meridiano de París calculado por François Arago, diseña 135 medallones de bronce de 12 centímetros de diámetros que fueron colocados en el suelo de la ciudad a lo largo del meridiano en dirección sur a norte.

Los medallones indicando la línea Arago a su paso por el Museo del Louvre.

Muchos de estos medallones han desaparecido con el tiempo, bien por robo o por pérdida. Otros se encuentran en muy mal estado y se distinguen por su forma no por ser legibles o reconocibles por algún signo. Otros muchos están en buen estado y es una tarea difícil y ardua ir en su busca.

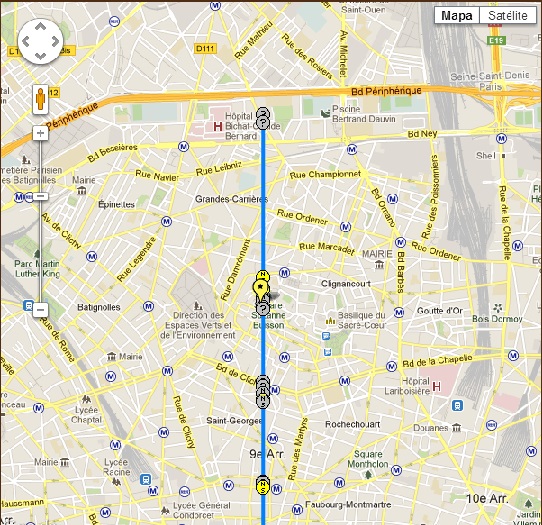

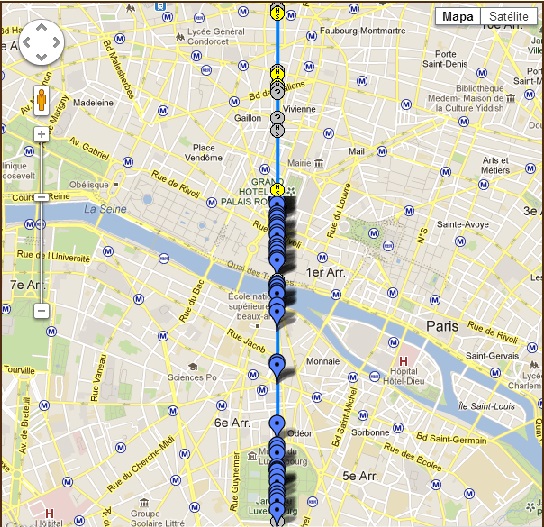

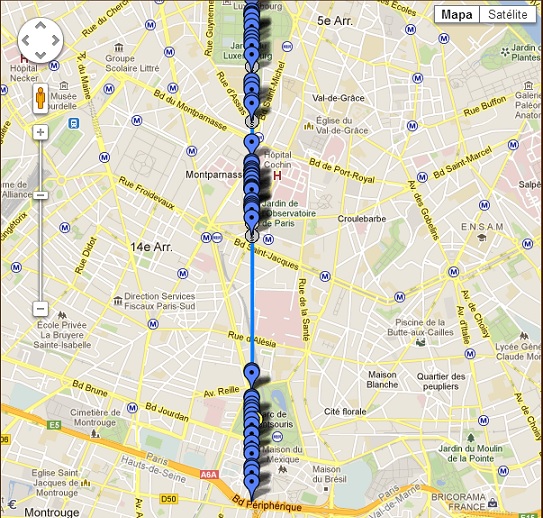

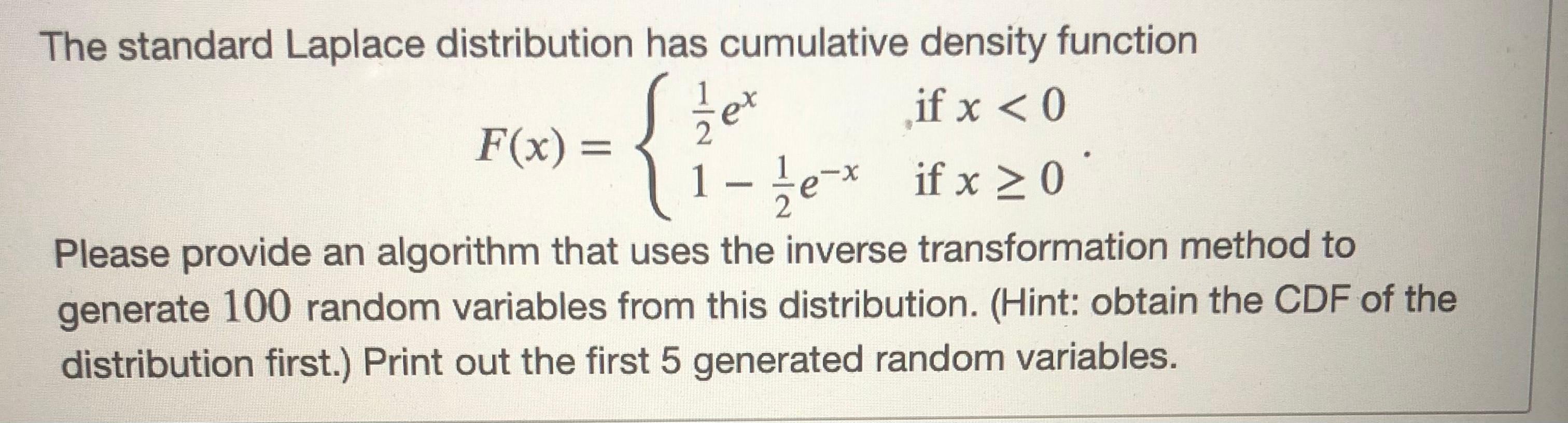

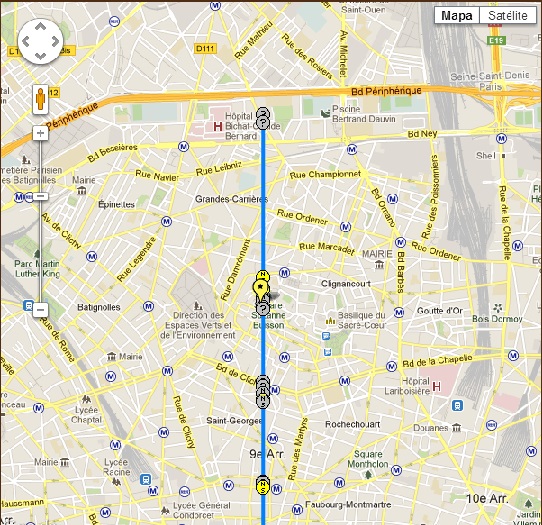

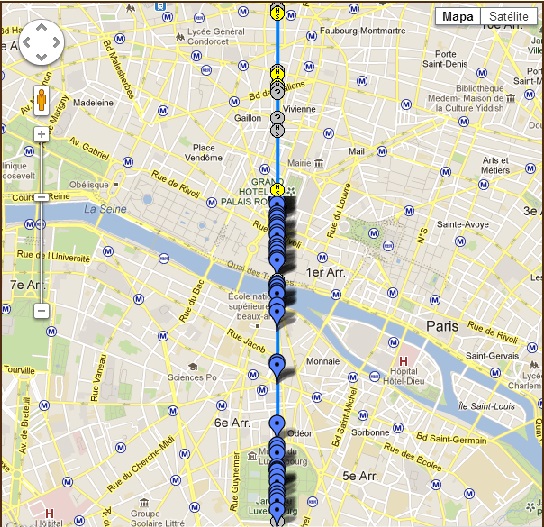

Aquí os acompaño de un plano para quien quiera hacerlo. Armaos de paciencia porque un meridiano (aunque sea sólo sobre París) no se recorre en un sólo día.

Casa natal de Pierre-Simon Laplace. Fuente: Wikimedia Commons

Casa natal de Pierre-Simon Laplace. Fuente: Wikimedia Commons Grabado del cadete Napoleón Bonaparte en la Escuela Militar de París en 1784. Fuente: www.elgrancapitan.org/foro

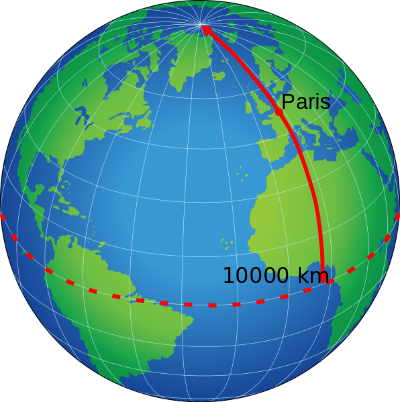

Grabado del cadete Napoleón Bonaparte en la Escuela Militar de París en 1784. Fuente: www.elgrancapitan.org/foro El metro se definió como el metro como la diezmillonésima parte de la distancia media del Polo Norte al Ecuador. Fuente: https://www.wikiwand.com/es/Sistema_m%C3%A9trico_decimal

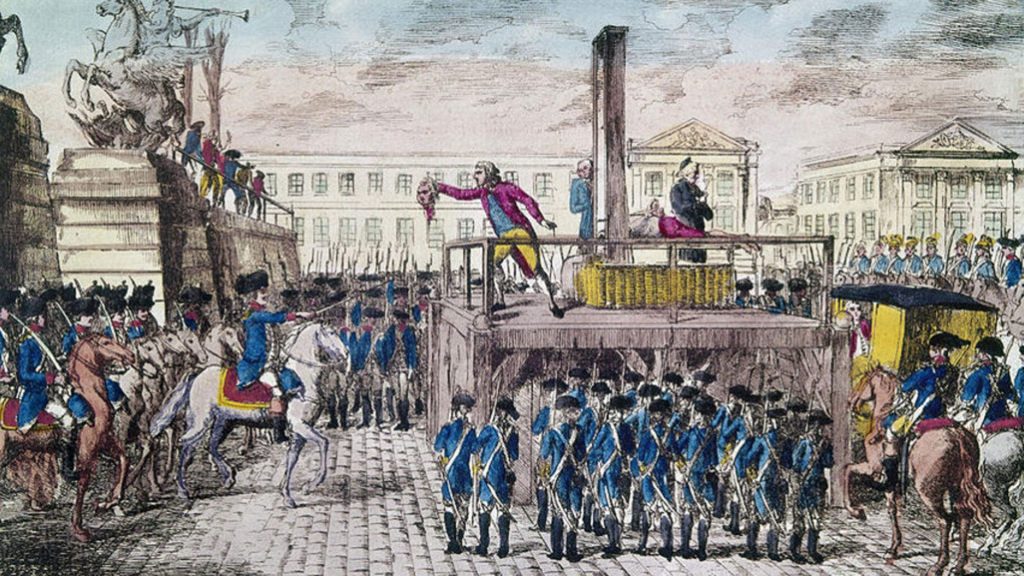

El metro se definió como el metro como la diezmillonésima parte de la distancia media del Polo Norte al Ecuador. Fuente: https://www.wikiwand.com/es/Sistema_m%C3%A9trico_decimal Lavoisier muerte guillotinado el 8 de mayo de 1794. Fuente: https://www.infobae.com/america/historia-america/2019/11/16/la-tragica-e-injusta-muerte-de-lavoisier-padre-de-la-quimica-moderna-guillotinado-por-venganza/

Lavoisier muerte guillotinado el 8 de mayo de 1794. Fuente: https://www.infobae.com/america/historia-america/2019/11/16/la-tragica-e-injusta-muerte-de-lavoisier-padre-de-la-quimica-moderna-guillotinado-por-venganza/

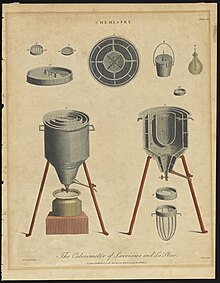

Cinco volúmenes de la Mecánica Celeste de Laplace. Fuente: https://www.astromia.com/biografias/laplace.htm

Cinco volúmenes de la Mecánica Celeste de Laplace. Fuente: https://www.astromia.com/biografias/laplace.htm Fuente: http://momentosestelaresdelaciencia.blogspot.com/2014/04/pierre-simon-laplace.html

Fuente: http://momentosestelaresdelaciencia.blogspot.com/2014/04/pierre-simon-laplace.html Foto de Laplace en Beaumont-en-Auge.

Foto de Laplace en Beaumont-en-Auge.

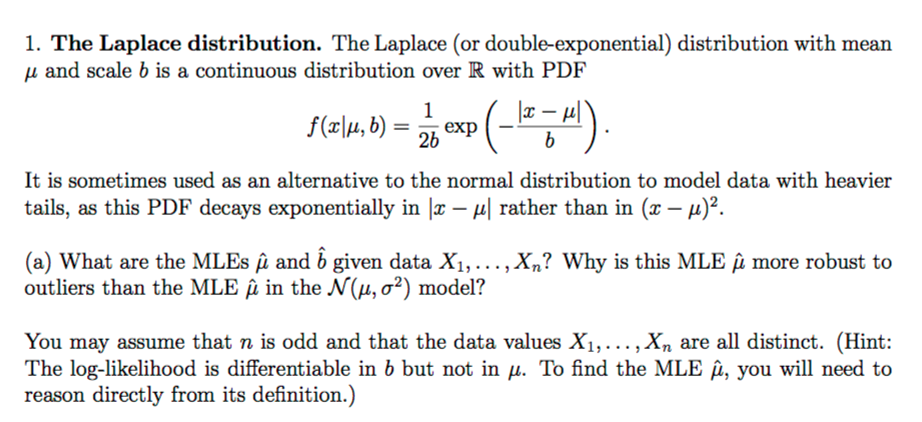

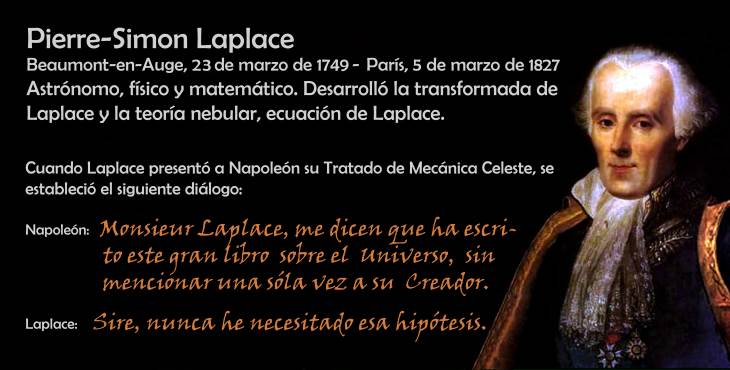

Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827), francés, fue el primero que demostró la siguiente relación, muy importante en el estudio de la

Pierre Simon de Laplace (1749-1827), francés, fue el primero que demostró la siguiente relación, muy importante en el estudio de la