|

|

General: ¿EL RELOJ CIRCULA MUCHO MAS DESPACIO EN BOLIVIA QUE EN EL RESTO DEL MUNDO?

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

Y SI, ESTA A MAS DE 3500 METROS DE ALTURA, POR LO MENOS, LA MAYORIA DEL PAIS.

|

|

|

|

|

Pero Dyson y Eddington decidieron que un solo punto de observación no sería suficiente. Era común que los resultados de expediciones como esa fueran perjudicados por malas condiciones meteorológicas, que a menudo impedían la visualización de los eclipses y hacían imposible tomar fotografías.

FUENTE DE LA IMAGEN,GETTY IMAGES

Pie de foto,

A consecuencia de la Primera Guerra Mundial, era casi imposible conseguir transporte y personal para las expediciones científicas.

"A pesar del riesgo, ellos estaban decididos a aprovechar esta oportunidad, porque sabían que el eclipse de 1919, con estrellas tan brillantes, sería especial", dice Daniel Kennefick.

Así Dyson y Eddington decidieron mandar dos equipos de astrónomos a lugares distintos: a Sobral, en Brasil, y a la Isla de Príncipe, parte del archipiélago de Santo Tomé y Príncipe, en la costa de África occidental.

¿Cómo hacerlo posible durante la Primera Guerra Mundial?

Los científicos tuvieron que encontrar maneras de solucionar otro problema: Europa todavía estaba en guerra y eso dificultaba enormemente cualquier expedición científica.

A pesar que Dyson utilizó su influencia para conseguir financiamiento y persuadir al gobierno británico de que su colega Eddington no fuera al frente, era muy difícil encontrar astrónomos experimentados y buques para llevarles a Sobral y a Príncipe.

"Eddington quiso ir a Príncipe, pero necesitó llevar con él un relojero del interior de Inglaterra, porque todos sus asistentes habían muerto en la guerra", cuenta Kennefick.

Dyson tuvo que quedarse en Inglaterra y, tras muchas dificultades, encontró dos candidatos para mandar a Sobral. Los afortunados serían Charles Davidson, un calculista sin formación académica pero con mucha experiencia en telescopios, y el astrónomo irlandés Andrew Crommelin, quien operaría el segundo telescopio llevado por seguridad.

FUENTE DE LA IMAGEN,OBSERVATORIO NACIONAL

Pie de foto,

Después de muchos cambios de planes, el calculista Charles Davidson y el astrónomo irlandés Andrew Crommelin fueron los elegidos para ir a Brasil.

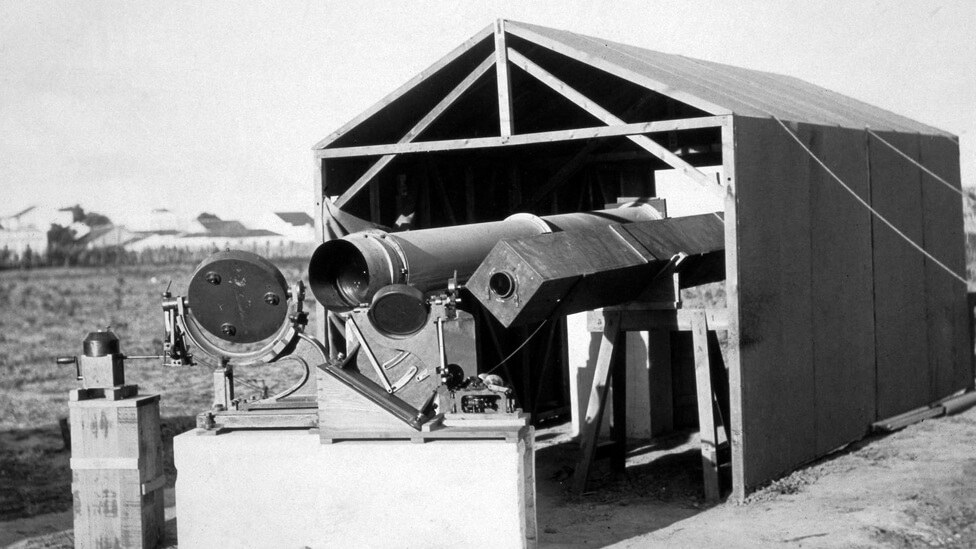

"Otro problema de la guerra era que los británicos tenían pocos instrumentos disponibles. Entonces tuvieron que pedir el segundo telescopio prestado a los irlandeses", dijo a BBC Mundo el astrofísico Tom Ray, del Instituto de Estudios Avanzados de Dublín, que encontró y restauró el equipo original que fue a Sobral.

El telescopio irlandés, a pesar de ser más pequeño y más viejo, fue el artífice de los resultados que hicieron historia.

En noviembre de 1918 el Armisticio de Compiègne anunció el fin de la Primera Guerra Mundial y abrió el camino para la expedición.

Eddington fue a Príncipe con su asistente y Davidson y Crommelin salieron de Liverpool, en Inglaterra, a Belém, al norte de Brasil, a bordo del "Anselm", el primer buque inglés que tras años de guerra reanudaba la ruta que cruzaba el océano Atlántico.

FUENTE DE LA IMAGEN,LUIZ CRISPINO | BIBLIOTECA ARTHUR VIANNA

Pie de foto,

El buque Anselm, que llevó los astrónomos británicos hasta Brasil, fue el primero en reanudar la ruta transatlántica después de la Primera Guerra.

El eclipse, por fin

La excitación en Sobral fue tan grande que, según la prensa de la época, el día del eclipse fue un festivo informal en la ciudad. Los comercios cerraron, la gente inundó las plazas y las iglesias se llenaron de fieles ante el miedo de que la oscuridad fuera un mal augurio.

El 29 de mayo de 1919 amaneció nublado. Por suerte, alrededor de un minuto antes de la cobertura total del Sol, el viento alejó las nubes y los investigadores tuvieron cerca de 4 minutos para hacer 27 fotografías del cielo, mostrando las 12 estrellas que planeaban observar.

Hubo un problema. El calor intenso en Sobral, según el físico Luis Carlos Bassalo Crispino, pudo haber causado una dilatación inusual en el espejo del principal telescopio y por lo tanto, algunas imágenes salieron distorsionadas. Eso las hacía menos confiables.

Por suerte, el segundo telescopio, el irlandés, produjo 8 imágenes nítidas e impresionantes del Sol cubierto por la sombra de la Luna y la luz de las estrellas.

Un mes más tarde, los científicos fotografiaron las mismas estrellas, exactamente en el mismo lugar en el cielo, sólo que por la noche.

Ya tenían lo que necesitaban para poner a Einstein a prueba.

En agosto de 1919, Davidson y Crommelin empezaron el camino de vuelta a Inglaterra.

Por su lado, Eddington tuvo menos suerte en Príncipe. El tiempo cerrado permitió pocas imágenes aprovechables y aparecían un número menor de estrellas.

Sus resultados ya parecían favorables a la teoría de Einstein, pero, sin base de comparación, crecía la ansiedad por la llegada de la expedición de Sobral.

El día que cambió la Física

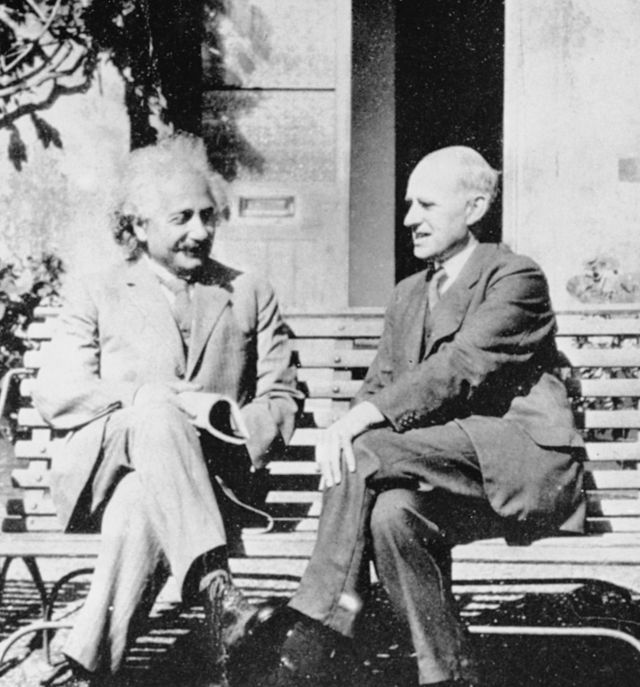

En noviembre de 1919, se publicó el estudio final sobre el eclipse, firmado por Dyson, Eddington y Davidson.

"Los resultados de las observaciones aquí descritas parecen apuntar definitivamente (...), y confirmar la teoría de la relatividad general de Einstein", dijo la publicación.

El trabajo también decía que las imágenes del telescopio irlandés de Sobral eran las más importantes y confiables. Era el primer experimento práctico hecho para confirmar la teoría del joven alemán.

"No todos quedaron convencidos. Los científicos continuaron haciendo mediciones en eclipses para comparar resultados. Y en los años 70, las imágenes del eclipse de 1919 fueron examinadas otra vez, con instrumentos más avanzados, para garantizar que sus resultados estaban correctos", dijo a BBC Mundo Virginia Trimble, profesora de Física y Astronomía en la Universidad de California Irvine, en EE.UU.

"De hecho, la teoría de la relatividad general fue testeada muchas veces y pasó perfectamente en todas las pruebas que le hicimos. Es impresionante."

FUENTE DE LA IMAGEN,SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Pie de foto,

Einstein y Eddington solo se encontraron en Inglaterra años después del eclipse. Aún había mucha tensión entre científicos británicos y alemanes por la Primera Guerra Mundial.

¿Cómo reaccionó Albert Einstein?

Einstein había recibido, en septiembre, un cable de un amigo de Holanda, diciéndole que los resultados de la expedición de Eddington a Príncipe, que aún eran inconclusos, apuntaban a la confirmación de su teoría.

Eddington ya hablaba de eso en conferencias, pero no pudo escribir a Einstein personalmente por los resquemores de la guerra que aún existían entre Inglaterra y Alemania.

"Einstein estaba muy ansioso por el experimento. Pero cuando el resultado finalmente le llegó, ya estaba tan convencido de la belleza y la coherencia de su teoría, que parecía no necesitar la comprobación", explica Daniel Kennefick.

"La filósofa alemana Rosenthal-Schneider y otras personas cercanas al alemán también observaron cuan sereno estaba ante la noticia. Todo el mundo a su alrededor estaba exaltado, era el cambio más importante en la física desde Newton, pero Einstein ya sabía que sus predicciones eran correctas", dice Kennefick.

De todas formas, el físico escribió a su madre enseguida para decirle que recibió la "feliz noticia" de que sus ideas fueron confirmadas.

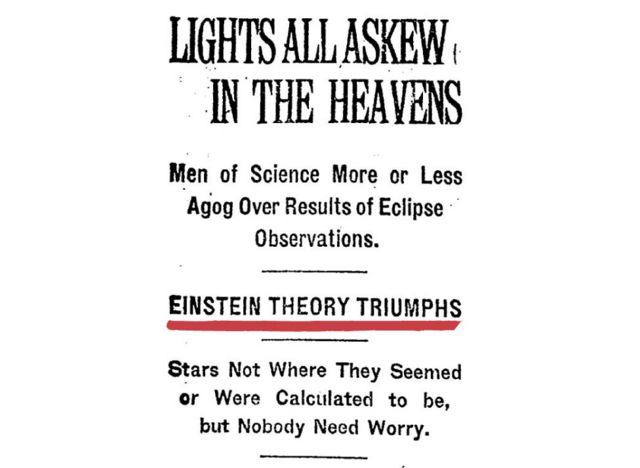

El 6 de noviembre, el resultado final fue anunciado en la Unión Astronómica Internacional. El filósofo y matemático Alfred North Whitehead, que estaba en la ceremonia, describió la escena como "de intensa emoción".

"Había un elemento dramático en todo aquel ceremonial tan escénico y tan tradicional, que tenía a Newton como telón de fondo y nos recordaba que la mayor de las generalizaciones científicas acababa de recibir su primera modificación en más de 200 años", escribió Whitehead.

FUENTE DE LA IMAGEN,NEW YORK TIMES

Pie de foto,

"La teoría de Einstein triunfa", decía la portada de New York Times publicada el 15 de noviembre de 1919.

Pero el propio Einstein se mantuvo humilde. En un artículo para el diario Times of London, el físico alemán dijo que "nadie debe pensar que la gran creación de Newton puede ser derrocada por esta o cualquier otra teoría".

"Sus ideas claras y amplias siempre tendrán el significado de bases sobre las cuales nuestra concepción moderna de la física fue construida", escribió.

En el mismo artículo, Einstein reconoce la "alegría y gratitud" que sentía por la oportunidad de comunicarse con científicos ingleses "después de la lamentable ruptura de relaciones internacionales entre hombres de la ciencia" que ocurrió durante la Primera Guerra Mundial.

El rencor a los alemanes y austríacos permaneció por mucho tiempo después de la guerra, pero Einstein se convirtió en una excepción. "En muchas conferencias científicas él era el único alemán invitado", dice Kennefick.

Pero más allá de la comunidad científica, Einstein también se convirtió en una celebridad mundial, y hasta admiradores lo paraban por la calle.

"Eso en realidad no le gustó mucho. No soportaba tener que hablar con reporteros todo el tiempo y llegó a decir que: "ese tormento es culpa de aquella expedición inglesa'", cuenta Kennefick.

Eso no amargó la alegría de ver confirmada su teoría de la relatividad, lo que Einstein llamaría "mi pensamiento más feliz".

Ilustraciones, gráficos yvideo: Cecilia Tombesi y Kako Abraham.

https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-48153620 |

|

|

|

|

Un nuevo reloj atómico mide la hora con una precisión sin precedentes

Además, este reloj de altísima precisión tiene otras aplicaciones más allá de dar la hora, por ejemplo para altímetros basados en cambios de la gravedad.

No atrasará ni adelantará un solo segundo en unos 15.000 millones de años -más o menos la edad del Universo-, una precisión casi inimaginable, pero que ahora es realidad gracias a las modificaciones que se han introducido a un reloj atómico de estroncio.

Científicos del Instituto Nacional del Estándares y Tecnología (NIST) de Estados Unidos han logrado con sus últimas modificaciones que el reloj gane en precisión y estabilidad, según un artículo publicado hoy por Nature Communications.

La cronometría tiene gran importancia en las comunicaciones avanzadas, las tecnologías de posicionamiento -el GPS- y otras muchas tecnologías, recordó en un comunicado el NIST.

Además, este reloj de altísima precisión tiene otras aplicaciones más allá de dar la hora, por ejemplo para altímetros basados en cambios de la gravedad y experimentos sobre las correlaciones cuánticas entre átomos.

El reloj creado por el JILA (un instituto conjunto del NIST y la Universidad de Colorado) es ahora «tres veces mas preciso que el año pasado, cuando ya fijó un récord mundial», lo que le permite medir cambios diminutos en el paso del tiempo y la fuerza de la gravedad a alturas ligeramente diferentes.

Einstein ya había predicho esos efectos en su teoría de la relatividad, lo que significa, entre otras cosas, que los relojes caminan más rápido en elevaciones mayores, recuerda el artículo.

La explicación de toda esta precisión de récord se debe a que los científicos «toman literalmente la temperatura» ambiental de los átomos.

Para ello, dos termómetros especializados, calibrados por investigadores del NIST, se insertan en una cámara de vacío que encierra un nube de átomos de estroncio confinados por láseres.

Ahora «podemos medir el desplazamiento gravitatorio cuando se levanta el reloj solo dos centímetros por encima de la superficie de la Tierra», explicó Jun Ye del JILA/NIST.

Además, consideró que con este nuevo avance están muy cerca de poder «ser útiles para la geodesia relativista», que es la idea de usar una red de relojes como si fueran sensores de gravedad para realizar mediciones de precisión en 3D de la forma de la Tierra.

https://www.la-razon.com/la-revista/2015/04/21/un-nuevo-reloj-atomico-mide-la-hora-con-una-precision-sin-precedentes/

|

|

|

|

|

La teoría de la relatividad especial nos dice que dos relojes que se están moviendo miden un distinto tiempo. Esto es sorprendente, pero, así funciona la naturaleza. Es más, la gravedad también afecta el flujo del tiempo. Un reloj en el piso de arriba de un edificio va mas rápido que uno en el piso más abajo. El efecto es muy, muy pequeño, pero se puede medir con los mejores relojes actuales. O sea que cuando queremos medir el tiempo con relojes, tenemos que tener en cuenta su movimiento y la gravedad.

De hecho, la Teoría de la Gravedad de Einstein dice que lo más fundamental es el hecho de que el fluir del tiempo es distinto, y que esto es lo que causa la gravedad.

El espacio y el tiempo están deformados, el tiempo fluye en forma distinta en distintos lugares. Este efecto fue mostrado en la película Interestelar, en donde los protagonistas van a un planeta donde este efecto es muy grande: una hora en la superficie es lo mismo que 7 años para los que se quedaron lejos. Esto es, en principio, posible. Eso sí: sería muy difícil regresar de ese planeta. No podría hacerse como en la película, donde esto ocurre gracias a los motores de la nave espacial, ya que la energía necesaria para volver a salir sería mucho mayor que la que puede llevar una nave espacial.

Entre los productores de Interestelar está el físico Kip Thorne, uno de los científicos que propusieron el detector que midió las ondas gravitacionales. Por eso les dieron un premio Nobel. En el filme, un personaje manda señales hacia atrás en el tiempo, luego de caer en un agujero negro. Yo creo que esto es imposible.

Uno podría tener la entrada del túnel en el Sistema Solar y la salida en una región distante de la galaxia. Al entrar, uno sentiría que cae libremente, como flotando en el espacio, como los astronautas en la Estación Espacial.

Juan Maldacena, físico

https://www.clarin.com/viva/escribe-juan-maldacena-posible-viajar-tiempo-_0_9YdpwT6NB.html |

|

|

|

|

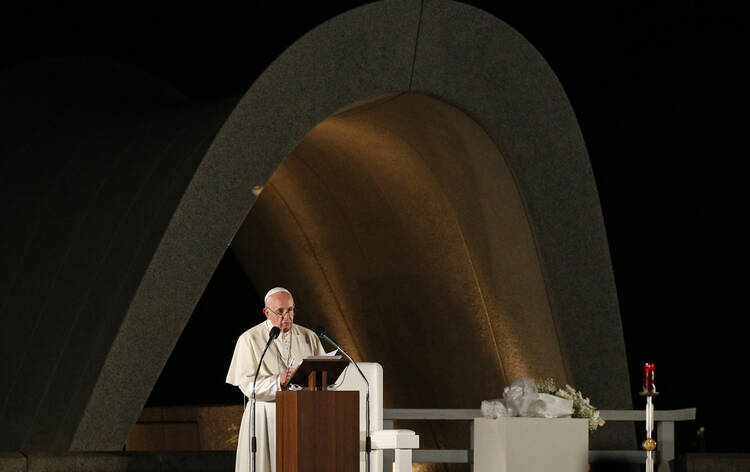

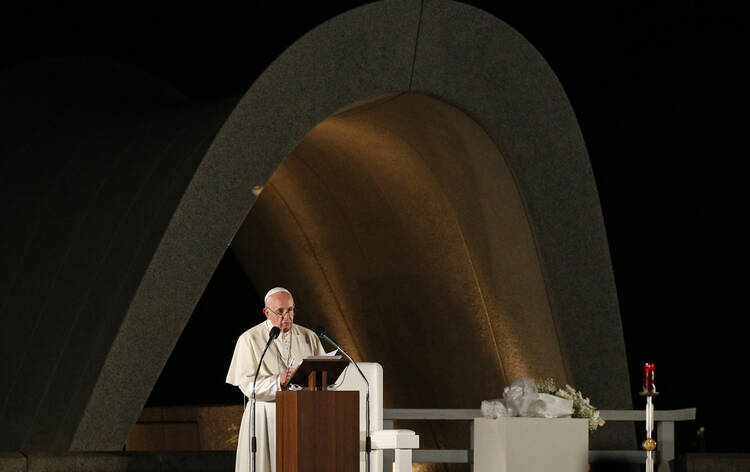

Pope Francis speaks during a meeting for peace at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in Hiroshima, Japan, Nov. 24, 2019. (CNS photo/Paul Haring) Pope Francis speaks during a meeting for peace at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in Hiroshima, Japan, Nov. 24, 2019. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

From Nagasaki and Hiroshima, the only two cities in the world to be destroyed by atomic bombs, Pope Francis made an impassioned appeal for the total elimination of nuclear arms. “The use of atomic energy for purposes of war is immoral, just as the possession of atomic weapons is immoral,” he said. “We will be judged on this.”

The pope spoke at the rain-drenched Atomic Bomb Hypocenter Park in Nagasaki on the morning of Nov. 24, near the spot where the United States dropped the second bomb on Aug. 9, 1945, instantly killing 27,000 people. Pope Francis declared that “the possession of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction is not the answer” to humanity’s deepest desire for “security, peace and stability.” In the evening, he visited the Peace Memorial in Hiroshima, honoring the tens of thousands killed by an atomic bomb there, too.

Ever since becoming pope in 2013, Francis wanted to come to these two sites of unprecedented destruction and suffering. He realized that wish today, and in speeches at both locations addressed the threat and use of nuclear arms, the ideology of mutually assured destruction, the arms race and the search for world peace. He is the second pope to come to these sites after John Paul II, who came in 1981.

Nagasaki

Pope Francis visited Nagasaki first, a city of some 400,000 people in the hill country that is the historic heartland of Catholicism in Japan and home to many martyrs.

He arrived at the park in the morning amid driving rain. There, at a place near the epicenter of the bomb explosion, Francis laid a wreath and prayed in silence in memory of those killed on that day. Then, after lighting a candle, he read his speech in Spanish to a crowd of some 200 Japanese, and to a global audience following on television.

Francis stated that “the possession of nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction is not the answer” to humanity’s desire for security, stability and peace in the world. Indeed, he said, “our world is marked by a perverse dichotomy that tries to defend and ensure stability and peace through a false sense of security sustained by a mentality of fear and mistrust, one that ends up poisoning relationships between peoples and obstructing any form of dialogue.”

He declared that “peace and international stability are incompatible with attempts to build upon the fear of mutual destruction or the threat of total annihilation.”

Recalling “the catastrophic humanitarian and environmental consequences of a nuclear attack” that Nagasaki witnessed, Francis said, “our attempts to speak out against the arms race will never be enough.”

He went on to forcefully denounce the arms race because “in a world where millions of children and families live in inhumane conditions, the money that is squandered and the fortunes made through the manufacture, upgrading, maintenance and sale of ever more destructive weapons, are an affront crying out to heaven.”

“In a world where millions of children and families live in inhumane conditions, the money that is squandered and the fortunes made through the manufacture, upgrading, maintenance and sale of ever more destructive weapons, are an affront crying out to heaven.”

He stated unequivocally that “the Catholic Church is irrevocably committed to promoting peace between peoples and nations.” He insisted that “we must never grow weary of working to support the principal international legal instruments of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, including the Treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.” He recalled with approval that last July “the bishops of Japan launched an appeal for the abolition of nuclear arms.”

Then, saying he is personally convinced that “a world without nuclear weapons is possible and necessary,” Pope Francis called on the world’s political leaders “not to forget that these weapons cannot protect us from current threats to national and international security.” He called on them “to ponder the catastrophic impact of their deployment, especially from a humanitarian and environmental standpoint, and reject heightening a climate of fear, mistrust and hostility fomented by nuclear doctrines.” He emphasized the need to create instruments “for ensuring trust and reciprocal development” and the need for “leaders capable of rising to these occasions.”

The Vatican has expressed increasing concern about U.S. President Donald Trump’s continuing delay in beginning talks with Russia on extending or renewing the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty and for allowing the U.S.-Russian treaty on intermediate-range weapons to expire.

The pope invited people to join him “in praying each day for the conversion of hearts and for the triumph of a culture of life, reconciliation and fraternity,” and suggested that they make their own the prayer of Saint Francis of Assisi: “Lord make me an instrument of your peace.”

From there, Francis went to the memorial of the Nagaski martyrs, whose memories had so inspired him as a young man that he wanted to come to Japan as a missionary, and then celebrated Mass in a baseball stadium.

Hiroshima

Later in the afternoon he took a one-hour plane ride from Nagaski to Hiroshima, a city of almost 2 million people. The sun had set when he arrived at the Peace Memorial in Hiroshima, which stands under the place where the United States, in agreement with the United Kingdom, dropped the world’s first atomic bomb that immediately killed between 60,000 and 80,000 people and a total of 140,000 by the end of that year.

Victims of the 1945 atomic bombing observe a moment of silence during a meeting for peace led by Pope Francis at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial in Hiroshima, Japan, Nov. 24, 2019. (CNS photo/Paul Haring)

It was evening when Pope Francis reached the memorial. Some 1,500 Japanese were present for the solemn event, together with 20 religious leaders and 20 survivors of that bombing. There was a long period of great silence as Francis greeted all the survivors one by one, and embraced one woman who was in tears. Francis then laid flowers in memory of the victims and prayed in silence. He then lit a candle made by the Roman Curia for the occasion. Then everyone was invited to stand for a moment of silence as a gong sounded.

Then two survivors, Yoshiko Kajimoto who was 14, and Kojí Hosokawa, who was 17

and living in Hiroshima when the bomb exploded, described with dignity and emotion their terrible experience to Francis.

Ms. Kajimoto was working in a factory when the bomb was dropped. She was buried under timber and tiles, but eventually managed to get free. “When I went outside, all the surrounding buildings were destroyed,” she told the pope. “It was as dark as evening and smelled like rotten fish.”

Helping evacuate the injured, she saw “people walking side by side like ghosts, people whose whole body was so burnt that I could not tell the difference between men and women, their hair standing on end, their faces swollen to double size, their lips hanging loose, with both hands held out with burnt skin hanging from them.”

“No one in this world can imagine such a scene of hell,” she said.

Mr. Hosokawa, was not able to attend the ceremony with the pope, but his testimony was read out: “I think everyone should realize that the atomic bombs were dropped, not on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but on all humanity,” he wrote.

After listening to the two testimonies, Francis began by saying “peace be with you” and recalling what happened when the bomb fell: “In barely an instant, everything was devoured by a black hole of destruction and death. From that abyss of silence, we continue even today to hear the cries of those who are no longer. They came from different places, had different names, and some spoke different languages. Yet all were united in the same fate, in a terrifying hour that left its mark forever not only on the history of this country, but on the face of humanity.”

He told those present, “I felt a duty to come here as a pilgrim of peace, to stand in silent prayer, to recall the innocent victims of such violence, and to bear in my heart the prayers and yearnings of the men and women of our time, especially the young, who long for peace, who work for peace and who sacrifice themselves for peace. I have come to this place of memory and of hope for the future, bringing with me the cry of the poor who are always the most helpless victims of hatred and conflict.”

He denounced “the use of atomic energy for purposes of war” as “a crime” against humanity and “immoral.” He added, “so too the possession of nuclear weapons is immoral, as I said already two years ago.”

Nine states have nuclear weapons: the United States, Russia, China, France, the United Kingdom, Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea. The United States and Russia together have 14,000 of the 15,000 nuclear weapons known to exist in the world and 2,000 of these are said to be still on “high alert.” Francis has expressed deep concerned that such weapons could be triggered by accident or human error, and so in Nov. 2017 he categorically condemned not only “the threat of their use” but also “their very possession,” the first pope to do so.

He told his global audience in Hiroshima, “future generations will rise to condemn our failure if we spoke of peace but did not act to bring it about among the peoples of the earth. How can we speak of peace even as we build terrifying new weapons of war? How can we speak about peace even as we justify illegitimate actions by speeches filled with discrimination and hate?”

Pope Francis prayed that “the abyss of pain endured here may remind us of boundaries that must never be crossed.”

At the day’s end, Pope Francis took the one-hour plane ride to Tokyo, where tomorrow he will meet the emperor and prime minister of Japan.

|

|

|

|

|

Time in General Relativity

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Describe how Einsteinian gravity slows clocks and can decrease a light wave’s frequency of oscillation

- Recognize that the gravitational decrease in a light wave’s frequency is compensated by an increase in the light wave’s wavelength—the so-called gravitational redshift—so that the light continues to travel at constant speed

General relativity theory makes various predictions about the behavior of space and time. One of these predictions, put in everyday terms, is that the stronger the gravity, the slower the pace of time. Such a statement goes very much counter to our intuitive sense of time as a flow that we all share. Time has always seemed the most democratic of concepts: all of us, regardless of wealth or status, appear to move together from the cradle to the grave in the great current of time.

But Einstein argued that it only seems this way to us because all humans so far have lived and died in the gravitational environment of Earth. We have had no chance to test the idea that the pace of time might depend on the strength of gravity, because we have not experienced radically different gravities. Moreover, the differences in the flow of time are extremely small until truly large masses are involved. Nevertheless, Einstein’s prediction has now been tested, both on Earth and in space.

The Tests of Time

An ingenious experiment in 1959 used the most accurate atomic clock known to compare time measurements on the ground floor and the top floor of the physics building at Harvard University. For a clock, the experimenters used the frequency (the number of cycles per second) of gamma rays emitted by radioactive cobalt. Einstein’s theory predicts that such a cobalt clock on the ground floor, being a bit closer to Earth’s center of gravity, should run very slightly slower than the same clock on the top floor. This is precisely what the experiments observed. Later, atomic clocks were taken up in high-flying aircraft and even on one of the Gemini space flights. In each case, the clocks farther from Earth ran a bit faster. While in 1959 it didn’t matter much if the clock at the top of the building ran faster than the clock in the basement, today that effect is highly relevant. Every smartphone or device that synchronizes with a GPS must correct for this (as we will see in the next section) since the clocks on satellites will run faster than clocks on Earth.

The effect is more pronounced if the gravity involved is the Sun’s and not Earth’s. If stronger gravity slows the pace of time, then it will take longer for a light or radio wave that passes very near the edge of the Sun to reach Earth than we would expect on the basis of Newton’s law of gravity. (It takes longer because spacetime is curved in the vicinity of the Sun.) The smaller the distance between the ray of light and the edge of the Sun at closest approach, the longer will be the delay in the arrival time.

In November 1976, when the two Viking spacecraft were operating on the surface of Mars, the planet went behind the Sun as seen from Earth (Figure 1). Scientists had preprogrammed Viking to send a radio wave toward Earth that would go extremely close to the outer regions of the Sun. According to general relativity, there would be a delay because the radio wave would be passing through a region where time ran more slowly. The experiment was able to confirm Einstein’s theory to within 0.1%.

![Time Delays for Radio Waves near the Sun. The curvature of spacetime near the Sun is shown in this diagram with the Sun at the bottom of a sag (similar to that illustrated in Figure 24_03_Spacetime]). The Viking spacecraft is at upper right, the Earth is at lower left and the Sun is between the two. The radio signal from Viking is drawn as a red arrow that goes down into the](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/1095/2016/11/03170628/OSC_Astro_24_05_Waves.jpg)

Figure 1. Time Delays for Radio Waves near the Sun: Radio signals from the Viking lander on Mars were delayed when they passed near the Sun, where spacetime is curved relatively strongly. In this picture, spacetime is pictured as a two-dimensional rubber sheet.

Gravitational Redshift

What does it mean to say that time runs more slowly? When light emerges from a region of strong gravity where time slows down, the light experiences a change in its frequency and wavelength. To understand what happens, let’s recall that a wave of light is a repeating phenomenon—crest follows crest with great regularity. In this sense, each light wave is a little clock, keeping time with its wave cycle. If stronger gravity slows down the pace of time (relative to an outside observer), then the rate at which crest follows crest must be correspondingly slower—that is, the waves become less frequent.

To maintain constant light speed (the key postulate in Einstein’s theories of special and general relativity), the lower frequency must be compensated by a longer wavelength. This kind of increase in wavelength (when caused by the motion of the source) is what we called a redshift in Radiation and Spectra. Here, because it is gravity and not motion that produces the longer wavelengths, we call the effect a gravitational redshift.

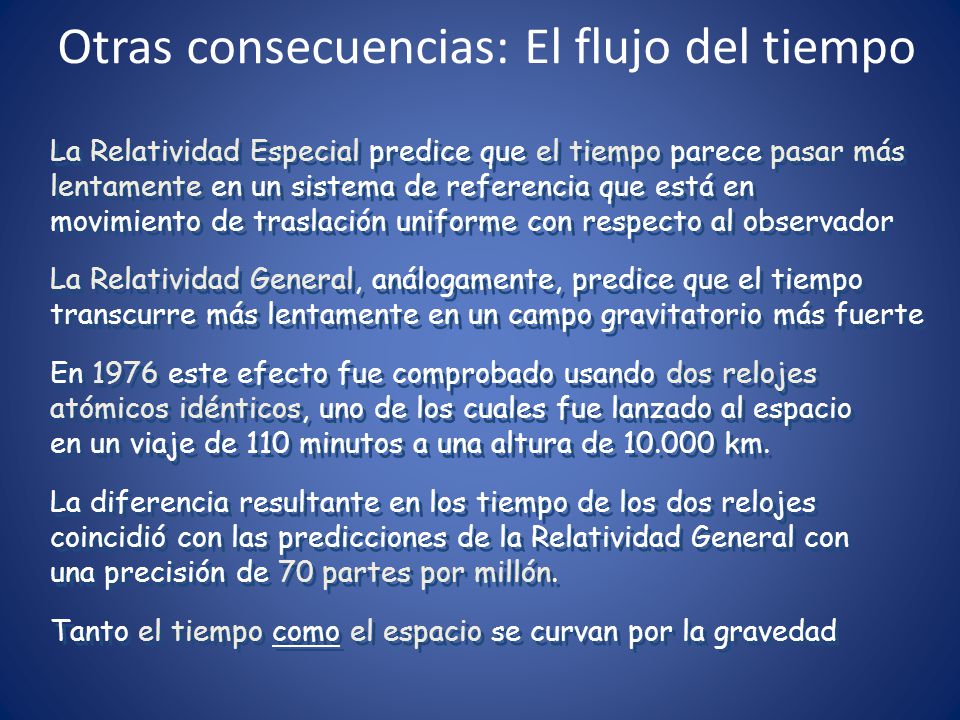

The advent of space-age technology made it possible to measure gravitational redshift with very high accuracy. In the mid-1970s, a hydrogen maser, a device akin to a laser that produces a microwave radio signal at a particular wavelength, was carried by a rocket to an altitude of 10,000 kilometers. Instruments on the ground were used to compare the frequency of the signal emitted by the rocket-borne maser with that from a similar maser on Earth. The experiment showed that the stronger gravitational field at Earth’s surface really did slow the flow of time relative to that measured by the maser in the rocket. The observed effect matched the predictions of general relativity to within a few parts in 100,000.

These are only a few examples of tests that have confirmed the predictions of general relativity. Today, general relativity is accepted as our best description of gravity and is used by astronomers and physicists to understand the behavior of the centers of galaxies, the beginning of the universe, and the subject with which we began this chapter—the death of truly massive stars.

Relativity: A Practical Application

By now you may be asking: why should I be bothered with relativity? Can’t I live my life perfectly well without it? The answer is you can’t. Every time a pilot lands an airplane or you use a GPS to determine where you are on a drive or hike in the back country, you (or at least your GPS-enabled device) must take the effects of both general and special relativity into account.

GPS relies on an array of 24 satellites orbiting the Earth, and at least 4 of them are visible from any spot on Earth. Each satellite carries a precise atomic clock. Your GPS receiver detects the signals from those satellites that are overhead and calculates your position based on the time that it has taken those signals to reach you. Suppose you want to know where you are within 50 feet (GPS devices can actually do much better than this). Since it takes only 50 billionths of a second for light to travel 50 feet, the clocks on the satellites must be synchronized to at least this accuracy—and relativistic effects must therefore be taken into account.

The clocks on the satellites are orbiting Earth at a speed of 14,000 kilometers per hour and are moving much faster than clocks on the surface of Earth. According to Einstein’s theory of relativity, the clocks on the satellites are ticking more slowly than Earth-based clocks by about 7 millionths of a second per day. (We have not discussed the special theory of relativity, which deals with changes when objects move very fast, so you’ll have to take our word for this part.)

The orbits of the satellites are 20,000 kilometers above Earth, where gravity is about four times weaker than at Earth’s surface. General relativity says that the orbiting clocks should tick about 45 millionths of a second faster than they would on Earth. The net effect is that the time on a satellite clock advances by about 38 microseconds per day. If these relativistic effects were not taken into account, navigational errors would start to add up and positions would be off by about 7 miles in only a single day.

KEY CONCEPTS AND SUMMARY

General relativity predicts that the stronger the gravity, the more slowly time must run. Experiments on Earth and with spacecraft have confirmed this prediction with remarkable accuracy. When light or other radiation emerges from a compact smaller remnant, such as a white dwarf or neutron star, it shows a gravitational redshift due to the slowing of time.

Glossary

gravitational redshift:

an increase in wavelength of an electromagnetic wave (light) when propagating from or near a massive object

https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-astronomy/chapter/time-in-general-relativity/#:~:text=Scientists%20had%20preprogrammed%20Viking%20to,where%20time%20ran%20more%20slowly. |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

3 a 17 de 17

Siguiente Anterior

3 a 17 de 17

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|

![Cuba, Isla Mía : ¿Volvería Albert Einstein a escribir "¿Por qué la guerra?" [+ video]](http://4.bp.blogspot.com/-U2MtBxY8tNA/U9hnsqjgtxI/AAAAAAAAmV4/hRoZ9LtfV74/s1600/cita-001.jpg)

Astrónomos brasileños, estadounidenses y británicos fueron a hacer experimentos durante el eclipse en Sobral. Foto: Observatorio Nacional de Brasil.

Astrónomos brasileños, estadounidenses y británicos fueron a hacer experimentos durante el eclipse en Sobral. Foto: Observatorio Nacional de Brasil. Los británicos llevaron instrumentos que permitieron proyectar los rayos solares sobre un punto fijo. Dos espejos móviles reflejaban la imagen del Sol hacia los telescopios. Foto: Museo de Ciencia de Londres

Los británicos llevaron instrumentos que permitieron proyectar los rayos solares sobre un punto fijo. Dos espejos móviles reflejaban la imagen del Sol hacia los telescopios. Foto: Museo de Ciencia de Londres Los científicos montaron su campamento de observación en el hipódromo de Sobral. Foto: Instituto de Ciencia Carnegie, Departmento de Magnetismo Terrestre.

Los científicos montaron su campamento de observación en el hipódromo de Sobral. Foto: Instituto de Ciencia Carnegie, Departmento de Magnetismo Terrestre. El día del eclipse, los habitantes de Sobral rompieron la puerta de una casa para usar los pedazos de vidrio como filtro para mirar directamente al Sol. Foto: Observatorio Nacional de Brasil

El día del eclipse, los habitantes de Sobral rompieron la puerta de una casa para usar los pedazos de vidrio como filtro para mirar directamente al Sol. Foto: Observatorio Nacional de Brasil Al comparar la posición de las estrellas Híades en el cielo durante el eclipse y después por la noche, los científicos confirmaron que Einstein tenía razón sobre la gravedad. Foto: Museo Marítimo de Londres.

Al comparar la posición de las estrellas Híades en el cielo durante el eclipse y después por la noche, los científicos confirmaron que Einstein tenía razón sobre la gravedad. Foto: Museo Marítimo de Londres.

![Time Delays for Radio Waves near the Sun. The curvature of spacetime near the Sun is shown in this diagram with the Sun at the bottom of a sag (similar to that illustrated in Figure 24_03_Spacetime]). The Viking spacecraft is at upper right, the Earth is at lower left and the Sun is between the two. The radio signal from Viking is drawn as a red arrow that goes down into the](https://s3-us-west-2.amazonaws.com/courses-images/wp-content/uploads/sites/1095/2016/11/03170628/OSC_Astro_24_05_Waves.jpg)