|

|

General: TROYES CATHEDRAL FRANCE CATHOLIC CHURCH GOTHIC BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX MADELEINE

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

Troyes Cathedral

Cathedral in Aube, France / From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

DEAR WIKIWAND AI, LET'S KEEP IT SHORT BY SIMPLY ANSWERING THESE KEY QUESTIONS:

Can you list the top facts and stats about Troyes Cathedral?

Summarize this article for a 10 year old

SHOW ALL QUESTIONS

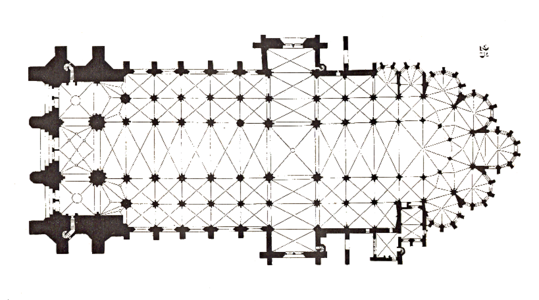

Troyes Cathedral (French: Cathédrale Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul de Troyes) is a Catholic church, dedicated to Saint Peter and Saint Paul, located in the town of Troyes in Champagne, France. It is the episcopal seat of the Bishop of Troyes. The cathedral, in the Gothic architectural style, has been a listed monument historique since 1862.

Quick Facts Troyes Cathedral Cathédrale Saint-Pierre-et-Saint-Paul, Religion ...

Close

Earlier cathedrals

According to local church tradition, Christianity was carried to Troyes in the third century by the Bishop of Sens, Savinien, who sent Saint Potentien and Saint Sérotin to the town to establish the first church. The house where they lived is believed to have stood on the same site as the cathedral; and excavations in the 19th century found traces of Gallo-Roman building under the sanctuary. A 5th-century bishop of Troyes, Lupus was credited with saving Troyes from destruction by Huns by leading a delegation of clerics to appeal to Attila, in 451. An enamel of Lupus healing a deaf young woman is displayed in the cathedral; the old cathedral is visible in the background.

The first church was rebuilt and enlarged in the 9th century, but it was badly damaged by the Norman invasions at the end of the same century. It was rebuilt by Bishop Milo through about 980 in the Romanesque style. Fragments of the sculptural decoration of this old church were found in 1864 and are displayed in the south collateral aisle of the present church.

In the 12th century, the Romanesque church was enlarged with the addition of a bell tower and a chapel dedicated to the Virgin Mary. The church was the site of the Council of Troyes that opened on 13 January 1129, hosted by Pope Honorius II. At the urging of Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, the Council granted official status to the Order of the Knights Templar, which became immensely influential throughout Christendom.

-

An enamel of Lupus of Troyes, a 5th-century bishop, healing a deaf woman. The old Cathedral is visible in the background.

-

Gothic cathedral

In 1188 a fire destroyed much of the town, and badly damaged the cathedral. Reconstruction began in 1199 or 1200, started by Bishop Garnier de Traînel. Once the construction was underway, the Bishop departed on the Fourth Crusade in 1204, and brought back to Troyes a collection of precious relics for the cathedral treasury.

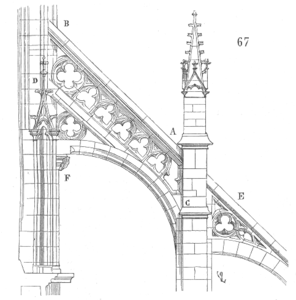

The new church was constructed in the Early Gothic style, inspired by the earlier Basilica of Saint Denis and Sens Cathedral, and by Chartres Cathedral and Notre Dame de Paris, which both were under construction at the same time. Work was well along by 1220 when the lower portions were completed and the upper walls were begun. Unfortunately, in 1228 a hurricane struck the half-finished structure, destroying the lower collateral aisle on the south side of the choir and damaging the upper walls. The upper walls were rebuilt between 1235 and 1240, and the builders took advantage of the extra time to adopt a more modern element first used at the Basilica of Saint-Denis; they filled the walls of the triforium, at the midlevel of the wall, with stained glass, bringing an abundance of light into the middle of the church.

The transept was finally vaulted in about 1310, and the spire was raised over the transept, but due to a series of economic difficulties, work slowed down. In 1365 a tornado destroyed the spire of the transept; it was not restored until 1437. More seriously, in 1389 the roof of the nave was struck by lightning, starting a fire that damaged the masonry below. This led in 1390 to the collapse of the rose window of the north transept. The rose was replaced and reinforced in 1408–9, but forty years later again showed signs of weakness. It was reinforced with a stone bar, and the portals were reinforced with new buttresses. Work resumed in 1450 under Bishop Louis Reguier, who worked to complete the upper portions of the nave.

Flamboyant and Renaissance additions (15th–17th century)

In May 1420, the Treaty of Troyes was signed in the cathedral between Henry V of England, his ally Philip of Burgundy and Queen Isabel, wife of the mad Charles VI of France whereby the throne of France would pass to Henry on the death of Charles rather than to Charles' son the Dauphin. Henry married Catherine of Valois, the French king's daughter, shortly afterwards in Troyes, either at the cathedral or the church of St Jean.

In July 1429, Joan of Arc escorted the Dauphin to Mass in the cathedral en route to proclaiming him Charles VII of France at Reims Cathedral, in contravention of the recently signed Treaty of Troyes.

At the beginning of the 16th century, a new building campaign began, this time in the late Gothic Flamboyant style. It was conducted by the master builder Martin Chambiges, whose works included the transepts of Sens Cathedral (1494), Beauvais Cathedral (1499) and Senlis Cathedral (1530). The new west front he designed followed the model of Reims Cathedral and other 13th century cathedrals, with three portals separated by strong buttresses, each topped by a high pointed arch.

The first level of the west front was finished by 1531–1432. The 12th-century bell tower and porch was demolished. The two levels were complete by 1554, and work began on the towers. Work on the north tower, called the Saint-Pierre tower, went slowly; it was not finished until 1634, and had just two of the smaller clochetons or steeples on the top corners instead of the four planned. The planned south tower was never started.

Vandalism and preservation (19th–20th century)

The cathedral suffered major damage during the French Revolution. The west front was particularly targeted; the sculptures that filled the tympanum over each portal were smashed. The lower stained glass windows in the choir were destroyed or taken apart. Fortunately, many of the upper windows were spared and still have their original glass. On January 9–10, 1794, a jeweller named Rondot led a mob that looted the treasury, seizing and melting down the previous gold and silver sacred objects.

During the rest of the 19th and 20th centuries, the cathedral underwent several campaigns of restoration. In 1840 the wall of the south transept, built on an unstable foundation, had to be reinforced to prevent it from collapsing, and between 1849 and 1866 all of the walls on the east side and then the pillars of the choir were reinforced. Many of the 13th-century windows were restored and put back into place. During both the First and Second World Wars, the stained glass was removed and put into safe storage, and the building suffered no significant harm. Restoration and repair of the west facade continued into the 21st century.

The cathedral, containing the nave, choir and apse with radiating chapels, has two principal aisles and two further subsidiary aisles. It is 114 metres (379 feet 6 inches) long and 50 metres (162 feet 6 inches) wide (across the transepts), with a height from the top of the vault of 29.5 metres (96 feet); the height of the cupola and the tower is 62.34 metres (202 feet 7 inches). The surface area of 1,500 m2 (16,000 sq. ft.),

West Front

The west front of the cathedral, with the three portals which serve as main entrances, was almost entirely redone beginning in 1507 in the Flamboyant style by master builder Martin Chambiges. It is divided into vertical sections containing the portals by four massive vertical buttresses and covered with elaborate arcades and tracery. Each of the three portals is crowned by a high pointed gable. The gable over the central portal originally held statues of the Virgin Mary, Saint John and Saint Mary Madeleine. An immense flamboyant rose window fills the space over the central portal. On top of the rose window, interrupting the balustrade, is the coat of arms of the city of Troyes

The west front suffered the most damage during the Revolution. The tympanum over the central entrance, which originally contained scenes from the Passion of Christ is bare; the statuary was smashed. The voussures and embracements that frame the portals preserve the original lavish vegetal decoration. The many niches and galleries on the west front contained statues, which were also destroyed, though the fleur-de-lis royal emblems on the balustrades remain. The sculpture of the tympanums of the north and south portals originally celebrated the lives of Saint Peter and Saint Paul, the two patron saints of the cathedral. These were also destroyed during the Revolution.

The north and only tower, finished in 1634, is built in a more classical Renaissance style. It has two narrow windows on each side, between the supporting buttresses. each side, and decoration of slender columns. The top has a balustrade with two cupolas. An arch was planned to connect the two towers, and its foundation was built, but the south tower was never constructed.

North and south sides and transepts

The north and south walls of the cathedral are supported by high flying buttresses, given additional weight by stone pinnacles. The walls are divided midway by the north and south transepts. The space between the buttresses is almost entirely filled by small chapels, lower than the central vessel of the nave and choir. A balustrade connects the roofs of the chapels, and another balustrade runs along the edge of the upper wall, at the base of the roof. The tracery of high windows and of the chapels, especially those closer to the west end of the cathedral, is flamboyant and elaborate, while the tracery toward the east end, built in the 13th and beginning of the 14th century, is simpler.

Midway along the sides are the two transepts, which protrude just beyond the chapels on either side of them. They were built in the 13th century, and each was originally decorated with sculpture in the tympanum, and in the voussures of the arches over the portals. The south portal sculpture depicted the Last Judgement and Apocalypse. The transept sculpture, like that of the west front, was destroyed during the Revolution. A few pieces are preserved in the Musée des beaux-arts de Troyes.

The north transept underwent major rebuilding. The buttresses with pinnacles were added in the 15th century, along with lancet and quadrafoil windows in the triforium, or middle level. and a balustrade with ornament representing the keys of Saint Peter. The original rose window of the transept fell in 1390, and was replaced with a Rayonnant window in the early 15th century. Later in the same century, a vertical stone bar was placed in front of the rose window to secure it.

The original south transept from the 13th century collapsed and was entirely rebuilt between 1841 and 1844. The rose window was made identical to that in the north facade, and the decoration was simplified.

|

|

|

|

|

Parish Church of the Madeleine, Troyes: Interior detail, statue of Saint Marthe

Date

Circa 1910

Creator

Architecture Library, Hesburgh Libraries

Sculpture produced in Troyes was abundant, if of uneven quality; about 1520 the work of the St. Martha workshop (named after a statue preserved in Ste. Madeleine) stands out.

Rebuilt around 1200 in the Gothic style. Its apse and choir were renovated around 1500 in the Flamboyant Gothic style. Its square Renaissance-style tower dates to 1525, as does the richly sculpted portal of the former cemetery located to the right of the entrance (today Jardin des Innocents). The church's main portal was refurbished in the 17th century and the nave was restored in the 19th century. It is noted for its Flamboyant rood (choir) screen (ca. 1508-1515, by Jean Gailde) and the stained glass of the apse. Sculpture produced in Troyes was abundant, if of uneven quality; about 1520 the work of the St. Martha workshop (named after a statue preserved in Ste Madeleine) stands out.

Metadata

- Creator

- G. Massiot & cie

- Date

- Circa 1910

- Publisher

- Architecture Library, Hesburgh Libraries

- Material Type

- photographs

- Conditions Governing Access

- To view the physical lantern slide, please contact the Architecture Library to arrange an appointment

- Related Location

- Troyes, Champagne-Ardenne, France

|

|

|

|

|

| San Bernardo de Claraval |

|

|

| Abad de Claraval |

| 1115-1128 |

|

| Otros títulos |

Doctor de la Iglesia

proclamado en 1830 por el papa Pío VIII |

| Información religiosa |

| Congregación |

Orden del Císter |

| Iglesia |

Iglesia católica |

| Culto público |

| Canonización |

18 de enero de 1174, por Alejandro III1 |

| Festividad |

20 de agosto |

| Atributos |

Báculo y libro |

| Venerado en |

Iglesia católica, Iglesia anglicana, Iglesia luterana |

| Patronazgo |

Gibraltar, Algeciras, San Bernardo del Viento, San Bernardo del Tuyú, Salta, apicultores |

| Santuario |

Catedral de Troyes, Troyes, Francia |

| Información personal |

| Nacimiento |

1090

Fontaine-lès-Dijon, Borgoña, |

| Fallecimiento |

20 de agosto de 1153 (63 años)

Abadía de Claraval, Ville-sous-la-Ferté |

| Padres |

Tescelin de Fontaine y Alèthe |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Su Orden del Císter[editar]

Abad del Císter[editar]

A los 23 años, en el año 1113, ingresó en la Orden del Císter. Dos años después, Esteban Harding, el abad de Císter, le envió a fundar una de las primeras fundaciones cistercienses, el monasterio de Claraval, del que fue designado abad, puesto que ocupó hasta el final de su vida.

La orden, entonces, estaba en formación. Esteban Harding era el tercer abad que tenía la orden, y en 1119 dotó al Císter de una regla propia, la Carta de caridad, en la que se establecían las normas comunitarias de total pobreza, de obediencia a los obispos y de dedicación al culto divino con dejación de las ciencias profanas.

Bernardo participó personalmente en la formación del espíritu cisterciense y fue el artífice de la gran difusión de la orden cisterciense, pasando del único monasterio cuando ingresó a 343 cuando murió, de los que 168 pertenecían a la filiación de Claraval y 68 fueron fundados por él mismo.

La enorme influencia que alcanzaron los cistercienses se debió a Bernardo que trascendió ampliamente a la orden. Ha sido la figura más destacada de la Orden y es venerado como fundador.28

Císter fue una concepción de la vida monástica medieval totalmente distinta a Cluny. La regla cisterciense era, en la práctica, una crítica de la de Cluny. Esta crítica a los cluniacenses, la concretó Bernardo en 1124, en su escrito Apología a Guillermo:

La iglesia relumbra por todas partes, pero los pobres tienen hambre. Los muros de la iglesia están cubiertos de oro, pero los hijos de la iglesia siguen desnudos. Por Dios, ya que no os avergonzáis de tantas estupideces, lamentad al menos tantos gastos.

Apología a Guillermo

A partir de la Apología a Guillermo, la regla cisterciense apareció como una reacción contra los excesos cluniacenses. Si durante el siglo xi los monjes cluniacenses habían asumido un gran protagonismo dentro de la iglesia, ocupando sus más altos cargos y ejerciendo su influencia sobre el poder civil, en el siglo xii ese papel les correspondió desempeñarlo a los cistercienses.

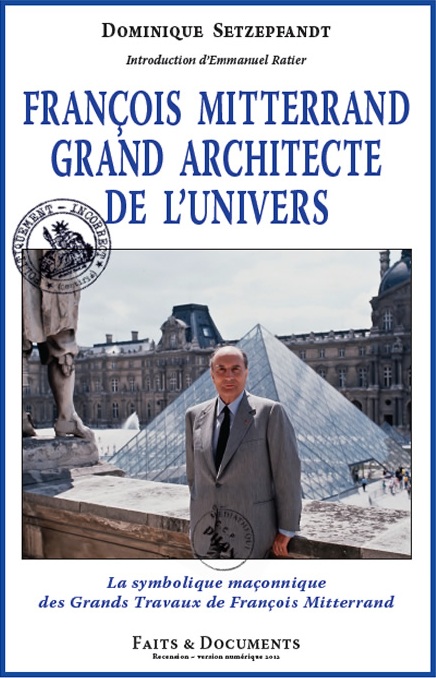

Inspirador de la arquitectura cisterciense[editar]

Claustro de la abadía de Fontenay

Su Apología a Guillermo estableció también los criterios teóricos que luego se emplearían en la construcción de todas las abadías cistercienses. En este escrito, Bernardo criticó duramente la escultura, la pintura, los adornos y las dimensiones excesivas de las Iglesias de los cluniacenses. Partiendo del espíritu cisterciense de pobreza y ascetismo riguroso, llegó a la conclusión de que sus monjes, que habían renunciado a las bondades del mundo, no precisaban de nada de esto para reflexionar en la ley de Dios. La crítica la desplegó sobre dos ejes. En primer lugar, la pobreza voluntaria: las esculturas y adornos eran un gasto inútil: despilfarran el pan de los pobres. En segundo lugar, rechazaba también las imágenes porque distraían la atención de los monjes, los apartaban de encontrar a Dios a través de la Escritura.

Cuando, en 1135, tenían unas 90 abadías y aumentaban a un ritmo de 10 nuevas por año, Bernardo debió pensar que la orden estaba consolidada y con un crecimiento desmedido siendo urgente un modelo de abadía que garantizase la uniformidad de la Orden. También debió reflexionar que la orden no podía seguir con las efímeras construcciones de madera y adobe, precisando monasterios en piedra que sirviesen a las generaciones futuras de monjes.

Ello lo concretó en la construcción en piedra de las dos primeras abadías, Claraval II (a partir de 1135) y Fontenay (comenzada en 1137), que se construyeron de forma simultánea. En las dos intervino de forma decisiva, ya que de Claraval era su abad y Fontenay era filial suya. Él fue el inspirador de ambas construcciones y de sus soluciones formales. Para él, la arquitectura cisterciense debía reflejar el ascetismo y la pobreza absoluta llevada hasta un desposeimiento total que practicaban a diario y que constituía el espíritu del Císter. Así terminó definiendo una estética de simplificación y desnudez que pretendía transmitir los ideales de la orden: silencio, contemplación, ascetismo y pobreza.

Estas primeras abadías se construyeron en estilo románico borgoñés, que había alcanzado toda su plenitud: (bóveda de cañón apuntada y bóveda de arista). Posteriormente, cuando en 1140, surgió el estilo gótico en la benedictina abadía de san Denis, los cistercienses aceptaron rápidamente algunos conceptos del nuevo estilo y empezaron a construir en los dos estilos, siendo frecuentes las abadías donde conviven dependencias románicas y góticas de la misma época. Con el paso del tiempo, el románico se abandonó.

Al prescindir de todo lo superfluo, el estilo cisterciense consiguió unos espacios desnudos, conceptuales y originales que lo hace plenamente identificable.

Influencia en el papa cisterciense Eugenio III[editar]

Eugenio III era hijo espiritual de Bernardo. Como se ha explicado, antes de ser elegido papa, estuvo 10 años en Claraval siendo monje bajo la autoridad espiritual de su abad Bernardo. Después, durante otros 5 años, fue abad de un monasterio filial de Claraval, por lo tanto, seguía manteniendo esa relación de dependencia espiritual.

Ya siendo papa, mantenían frecuente correspondencia entre ellos, pidiéndole Eugenio, que le escribiera un tratado sobre las obligaciones de ser papa. El abad así lo hizo y escribió el tratado De Consideratione en 5 libros. El primero lo escribió en 1149, el segundo en 1150, el tercero después del desastre de la cruzada en 1152 y los dos últimos a continuación. Es su tratado más conocido y aunque lo escribió para el papa Eugenio, en la práctica, lo estaba haciendo también para todos los papas posteriores. De hecho, se conoce la importancia que muchos papas han dado a este texto.

Bernardo seguía sintiéndose su padre espiritual, así lo manifestó repetidamente en el prólogo de De Consideratione: «el amor que os profeso no os considera como Señor, os reconoce por hijo suyo entre las insignias y el esplendor de vuestra excelsa dignidad...Os amé cuando eras pobre, igual os he de amar hecho padre de los pobres y de los ricos. Porque bien os conozco, no por haber sido hecho padre de los pobres dejáis de ser pobre de espíritu».

En este escrito, insiste en la necesidad de la vida interior y de la oración para aquellos que tienen las mayores responsabilidades de la Iglesia. Escribió sobre el peligro de dejarse llevar por los asuntos de Estado y descuidar la oración y las realidades de lo alto.

Sobre los poderes del papa, le escribió defendiendo la supremacía del poder espiritual y el derecho de la Iglesia a emplear los ejércitos seglares Se basaba en las palabras que los apóstoles dijeron a Jesús cuando lo apresaron, recogidas en el Evangelio de san Lucas, que él interpretó para fundamentar de nuevo «la doctrina de las dos espadas», presente en el pensamiento cristiano desde los inicios de la Edad Media:

Si la espada material no perteneciese a la Iglesia, el Señor no habría replicado «Es bastante» a los apóstoles cuando le dijeron «Aquí hay dos espadas», sino «Es demasiado». Por tanto, de la Iglesia son la espada espiritual y la espada material, pero esta ha de ser manejada para la Iglesia, y aquella, por la Iglesia.

De consideratione

También le escribió que el poder del papa no es ilimitado:

Yerras si, como creo, piensas que tu poder apostólico es el único instituido por Dios (dice el apóstol:) «No hay poder que no proceda de Dios...Todos han de estar sometidos a las autoridades superiores». No dice «la autoridad superior», como si se refiriese a una, sino «las autoridades superiores», como si se refiriese a varias. Por tanto, tu poder no es el único que procede de Dios, también proceden de «Él», el poder de los medianos y de los pequeños.

De consideratione

Estaba convencido de que todos los cargos de la Iglesia procedían directamente de Dios y así lo escribió al papa:

Reflexiona que la santa Iglesia romana no es la señora, sino la madre de las iglesias. Vos no sois el señor de los obispos, sino uno de ellos.

De consideratione

|

|

|

|

|

The Nard of Mary-Magdalene

My fools for senses,

Today, we shall be looking for an answer centuries of commentors failed to provide. Following our Review of Irrévérent and its unusual accord of oud and lavender, we decided to ponder awhile on this last ingredient which we thought we knew too well. Most of all, we wanted to envision it with a new eye : that of theology. Of history and literature and cooking and anthropology.

For indeed lavender passed through many cultures and through many readings did we stumble upon a most startling fact : that nard and lavender, in the Bible, are one. Thus, my fools for senses, let us discover today what really hid behind the Nard of Mary-Magdalene.

All good adventure movies start with a writing on a wall or in a book in our case. In the Bible, really. “Mary, having taken an ounce of pure nard anointed with it the feet of Jesus” This moving scene will very lively raise more than one question in the reader's mind : whatever is nard and why use it to anoint the Christ's feet ?

To properly grasp what nard is or was, one must look at its history and all the times it was mentioned. As far as we can tell around the Mediteranean Sea, Dioscorides spoke of nard in De Materia Medica. Of more than one actually. He lists a Syrian nard, an Indian nard and a Celtic nard. According to him, the Syrian nard got its name from the fact that it grows on the western slope of a mountain range -he was probably referring to the Hindu Kush. He also says its sweet aroma is close to that of nard from Cyprus. Indian nard is apparently smoother and more watery considering it grows in the Gange basin. The Celtic nard at last is both sweet and suave. He also mentions a wild nard growing in the mountains known already by the Gauls. As for Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History he lists a numerous variety of nards and one in particular that was so sweet-smelling that it was a most sought-after oil.

Roman literature is also a good resource when it comes to perfumes. In his Odes –the tenth to be more precise- Horace speaks of an « Assyrique nardo », Assyrian nard, whereas Petronius in his Cena Trimalchionis has one of his characters open an « ampullam nardi », a phial of nard, which was then rubbed on al the guests’ noses. Knowing the musty, musky scent of nard, one might be surprised upon reading so many lauds to it and the Roman nobility anointing their noses with it as they end a banquet. However, there happens to be mentions of nard in the Apicius, a Roman cookbook, according to which a few drops of nard might be useful to freshen a stale broth.

This occurrence of nard in a cookbook really raised our eyebrows and convinced us that nard was in fact lavender but how did the Romans end up confusing both ?

One must go back to the origins. Nard was named after the Assyrian city of Nuhadra –in actual Iraq- sitting on the banks of the Tigris river. Probably known for trading precious oils, one might say it was the starting point of spikenard trading routes going west into the Roman Empire although the nard existed way before the Romans. Already is it seen in a recipe for the anointing oil of Parthian kings as well as in Arrian’s Anabasis in a curious tale where the soldiers, as they traverse the desert of Gadrosia, find themselves trampling a « grass of nard » which then exhaled a sweet-smelling aroma. Research has now shown that this so-called nard was in fact…lemongrass.

To establish a link between the freshness of lemongrass and that of lavender isn’t much of a stretch.

Moreover, we looked for answers into the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which has gone uninterrupted since the early years of our era. After having ordered many an incense and nard-scented oils, we realised they were in fact all perfumed with lavender. Thus, we wondered why Mary-Magdalene anointed Jesus’ feet with nard –or lavender.

For so, let us dive into the writings. In the famous passage, St John writes : « nardou pistikes », « pure nard ». Some translated it into « true nard » as opposed to the fake one being lavender however we still think that « pistikes » has nothing to do with botanics. The Peshitta, an Aramaic translation of the Gospels, wrote : « dnardeen reeshaya ». Reeshaya here means « the best », of great quality. The symbolical use of the word reeshaya is most clearly seen in the Gospel of St Mark where Mary-Magdalene breaks « of pure nard. » on Jesus’ « head ». The Peshitta writes : « dnardeen reeshaya (…) al reesheh dyeshoo » a play on the words « reeshaya » which we’d roughly translate to : she poured the best on the Best.

Why pouring nard, though ? Or rather lavender ?

It is now known that myrrh is a symbol for death. It would thus have been very clever of Mary-Magdalene to anoint Jesus’ feet with it as a sign of his upcoming death and burial but she chose lavender. As such, her anointement is nothing short of a prophecy, lending us precious informations on the secret symbolism hidden behind lavender.

We read how the Ancients confused nard with lavender but we must now explain why they did so for they spoke of spikenard and lavender spike. The first bore its name from the fact its root looked like it was spiking out of the stem. The latter bore its name from its resemblance to an ear of wheat and this is precisely where we need investigate for therein lies the key to understanding the real meaning of lavender and solve a millenial controversy.

When Mary Magdalene poured lavender spike on Jesus’ feet, she accomplished a prophetic gesture of which she had probably no knowledge –as most prophecies in the New Testament. Along with St John whose head lies on Jesus’ chest - announcing the theosis- and the Virgin Mary who looked westward as her baby lay in her arms –announcing the Passion- Mary Magdalene announces the Passion and Resurrection. For as she poured the best on the Best, it is precisely the oil of the best ear of wheat which she poured upon He who compared himself to a « kernel of wheat ». This gesture is a clear reference to the words of Jesus saying on the eve of his death : « Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds »

The anointing of Jesus’ feet in the Gospel of Saint John heralds that of the myrrh-bearers and his Resurrection and of the Holy Spirit as it shone on his head upon his descent in the Hades, to a crown of light inextinguishable alike.

What we must understand is that lavender is akin to the light which shrouded the Christ as he went down into the Hades. Furthermore, mediaeval traditions will swiftly associate lavender to the virtue of keeping evil and dark spirits at bay. Lavender is a twig of life, fortifying the heart of Men ; it is the scent we smell as we leave a heartwarming feast, saying « I only hope it will give me as much pleasure when I'm dead as it does now when I'm alive. » It the the flower of foreseers, of those who see beyond appearances and the simple planes of existence.

The flower of they who want to trample and have trampled down death. The flower of soldiers as they traverse the desert, the flower of queens and kings chasing away all sorrows and withering of the soul.

Even more so than frankincense, lavender and its hues of violets and blues, is the perfect flower to connect us to the ethereal worlds. It clings to our soul and lifts it up and says to all and to us foremost that Love, over death, has won.

Your goodness and nard will follow me,

All the days of my life.

https://www.theperfumechronicles.com/chronicles/nard |

|

|

|

|

The Nard of Mary-Magdalene

My fools for senses,

Today, we shall be looking for an answer centuries of commentors failed to provide. Following our Review of Irrévérent and its unusual accord of oud and lavender, we decided to ponder awhile on this last ingredient which we thought we knew too well. Most of all, we wanted to envision it with a new eye : that of theology. Of history and literature and cooking and anthropology.

For indeed lavender passed through many cultures and through many readings did we stumble upon a most startling fact : that nard and lavender, in the Bible, are one. Thus, my fools for senses, let us discover today what really hid behind the Nard of Mary-Magdalene.

All good adventure movies start with a writing on a wall or in a book in our case. In the Bible, really. “Mary, having taken an ounce of pure nard anointed with it the feet of Jesus” This moving scene will very lively raise more than one question in the reader's mind : whatever is nard and why use it to anoint the Christ's feet ?

To properly grasp what nard is or was, one must look at its history and all the times it was mentioned. As far as we can tell around the Mediteranean Sea, Dioscorides spoke of nard in De Materia Medica. Of more than one actually. He lists a Syrian nard, an Indian nard and a Celtic nard. According to him, the Syrian nard got its name from the fact that it grows on the western slope of a mountain range -he was probably referring to the Hindu Kush. He also says its sweet aroma is close to that of nard from Cyprus. Indian nard is apparently smoother and more watery considering it grows in the Gange basin. The Celtic nard at last is both sweet and suave. He also mentions a wild nard growing in the mountains known already by the Gauls. As for Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History he lists a numerous variety of nards and one in particular that was so sweet-smelling that it was a most sought-after oil.

Roman literature is also a good resource when it comes to perfumes. In his Odes –the tenth to be more precise- Horace speaks of an « Assyrique nardo », Assyrian nard, whereas Petronius in his Cena Trimalchionis has one of his characters open an « ampullam nardi », a phial of nard, which was then rubbed on al the guests’ noses. Knowing the musty, musky scent of nard, one might be surprised upon reading so many lauds to it and the Roman nobility anointing their noses with it as they end a banquet. However, there happens to be mentions of nard in the Apicius, a Roman cookbook, according to which a few drops of nard might be useful to freshen a stale broth.

This occurrence of nard in a cookbook really raised our eyebrows and convinced us that nard was in fact lavender but how did the Romans end up confusing both ?

One must go back to the origins. Nard was named after the Assyrian city of Nuhadra –in actual Iraq- sitting on the banks of the Tigris river. Probably known for trading precious oils, one might say it was the starting point of spikenard trading routes going west into the Roman Empire although the nard existed way before the Romans. Already is it seen in a recipe for the anointing oil of Parthian kings as well as in Arrian’s Anabasis in a curious tale where the soldiers, as they traverse the desert of Gadrosia, find themselves trampling a « grass of nard » which then exhaled a sweet-smelling aroma. Research has now shown that this so-called nard was in fact…lemongrass.

To establish a link between the freshness of lemongrass and that of lavender isn’t much of a stretch.

Moreover, we looked for answers into the Eastern Orthodox tradition, which has gone uninterrupted since the early years of our era. After having ordered many an incense and nard-scented oils, we realised they were in fact all perfumed with lavender. Thus, we wondered why Mary-Magdalene anointed Jesus’ feet with nard –or lavender.

For so, let us dive into the writings. In the famous passage, St John writes : « nardou pistikes », « pure nard ». Some translated it into « true nard » as opposed to the fake one being lavender however we still think that « pistikes » has nothing to do with botanics. The Peshitta, an Aramaic translation of the Gospels, wrote : « dnardeen reeshaya ». Reeshaya here means « the best », of great quality. The symbolical use of the word reeshaya is most clearly seen in the Gospel of St Mark where Mary-Magdalene breaks « of pure nard. » on Jesus’ « head ». The Peshitta writes : « dnardeen reeshaya (…) al reesheh dyeshoo » a play on the words « reeshaya » which we’d roughly translate to : she poured the best on the Best.

Why pouring nard, though ? Or rather lavender ?

It is now known that myrrh is a symbol for death. It would thus have been very clever of Mary-Magdalene to anoint Jesus’ feet with it as a sign of his upcoming death and burial but she chose lavender. As such, her anointement is nothing short of a prophecy, lending us precious informations on the secret symbolism hidden behind lavender.

We read how the Ancients confused nard with lavender but we must now explain why they did so for they spoke of spikenard and lavender spike. The first bore its name from the fact its root looked like it was spiking out of the stem. The latter bore its name from its resemblance to an ear of wheat and this is precisely where we need investigate for therein lies the key to understanding the real meaning of lavender and solve a millenial controversy.

When Mary Magdalene poured lavender spike on Jesus’ feet, she accomplished a prophetic gesture of which she had probably no knowledge –as most prophecies in the New Testament. Along with St John whose head lies on Jesus’ chest - announcing the theosis- and the Virgin Mary who looked westward as her baby lay in her arms –announcing the Passion- Mary Magdalene announces the Passion and Resurrection. For as she poured the best on the Best, it is precisely the oil of the best ear of wheat which she poured upon He who compared himself to a « kernel of wheat ». This gesture is a clear reference to the words of Jesus saying on the eve of his death : « Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds »

The anointing of Jesus’ feet in the Gospel of Saint John heralds that of the myrrh-bearers and his Resurrection and of the Holy Spirit as it shone on his head upon his descent in the Hades, to a crown of light inextinguishable alike.

What we must understand is that lavender is akin to the light which shrouded the Christ as he went down into the Hades. Furthermore, mediaeval traditions will swiftly associate lavender to the virtue of keeping evil and dark spirits at bay. Lavender is a twig of life, fortifying the heart of Men ; it is the scent we smell as we leave a heartwarming feast, saying « I only hope it will give me as much pleasure when I'm dead as it does now when I'm alive. » It the the flower of foreseers, of those who see beyond appearances and the simple planes of existence.

The flower of they who want to trample and have trampled down death. The flower of soldiers as they traverse the desert, the flower of queens and kings chasing away all sorrows and withering of the soul.

Even more so than frankincense, lavender and its hues of violets and blues, is the perfect flower to connect us to the ethereal worlds. It clings to our soul and lifts it up and says to all and to us foremost that Love, over death, has won.

Your goodness and nard will follow me,

All the days of my life.

https://www.theperfumechronicles.com/chronicles/nard

|

|

|

|

|

Bernard of Clairvaux

Above: Bernard of Clairvaux

by Alan Butler

Born Fontaine de Dijon France 1090

Died Clairvaux, near Troyes, Champagne France August 20th 1153

Bernard of Clairvaux may well represent the most important figure in Templarism. In our opinion past researchers have generally failed to credit St Bernard with the pivotal role he played in the planning, formation and promotion of the infant Templar Order. Whether an ‘intention’ to create an Order of the Templar sort existed prior to the life of St Bernard himself is a matter open to debate. (See ‘The Templar Continuum’ Butler and Dafoe, Templar Books 2,000).

The son of Tocellyn de Sorrell, Bernard was born into a middle-ranking aristocratic family, which held sway over an important region of Burgundy, though with close contacts to the region of Champagne. There is some dispute as to whether Bernard’s father had fought in the storming of Jerusalem in 1099, and indeed whether he died in the Levant. The question appears to be easily answered for in the small Templar type Church in St Bernard’s birthplace there is a marble plaque that states the Church was built by St Bernard’s mother in thanks for the safe return of her husband from the Crusade.

St Bernard was a younger member of an extremely large family. He appears to have received a good, standard education, at Chatillon-sur-Seine, which fitted him, most probably, for a life in the Church, which, of course, is exactly the direction he eventually took. Many stories exist regarding Bernard’s early years – his visions, torments and realisations. All of these were attributed to Bernard after his canonisation and therefore must surely be taken with a pinch of salt. What does seem evident is that Bernard was bright, inquisitive and probably tinged with a sort of genius. Certainly he was a fantastic organiser and possessed a charisma that few could deny.

St Bernard enters history in an indisputable sense at the age of 23 years, when together with a very large group of his brothers, cousins and maybe other kin, (probably between 25 and 30) he rode into the abbey of Citeaux, Dijon. This abbey was the first Cistercian monastery and had been set up somewhat earlier by a small band of dissident monks from Molesmes. Much can be found elsewhere in these pages relating specifically to the Cistercians. At the time of St Bernard’s arrival the abbey was under the guiding hand of Stephen, later St Stephen Harding, an Englishman.

Bernard announced his determination to follow the Cistercian way of life and together with his entourage he swamped the small abbey, swelling the number of brothers there to such an extent that it was inevitable that more abbeys would have to be formed.

Only three years later St Bernard, still an extremely young man, (25 years) was dispatched, together with a small band of monks, to a site at Clairvaux, near Troyes, in Champagne, there to become Abbott of his own establishment. It is known that the land upon which Clairvaux was built was donated by the Count of Champagne, based at the nearby city of Troyes.

St Bernard was a visionary, a man of apparently tremendous religious conviction. He could be irascible and domineering at times, but seems to have been generally venerated and well liked by those around him. Bernard suffered frequent bouts of ill health, almost from the moment he joined the Cistercians. This continued for the remainder of his life and may have demonstrated an inability on the part of his digestive system to cope with the severe diet enjoyed or rather endured by the Cistercians at the time.

Bernard’s influence grew within the established Church of his day. With a mixture of simple, religious zeal and some extremely important family connections, this little man involved himself in the general running, not only of the Cistercian Order, but the Roman Church of his day. Bernard was instrumental in the appointment of GREGORIO PAPARESCHI, Pope Innocent II in the year 1130, despite the fact that not all agencies supported the man for the Papal throne. Bernard walked hundreds of miles and talked to a great number of influential people in order to ensure Innocent’s ultimate acceptance. His success in this endeavour marked St Bernard as probably the most powerful man in Christendom, for as ‘Pope Maker’ he probably had more influence than the Pontiff himself.

This appointment should not be underestimated, for it was Pope Innocent II who formally accepted ‘The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon’ (The Knights Templar) into the Catholic fold. This he did, almost certainly, at the behest of Bernard and possibly as a result of promises he had made to this end at the time Bernard showed him the support which led to the Vatican.

To understand St Bernard’s importance to Cistercianism it is first necessary to study the Order in detail. In brief however it would be fair to suggest that Bernard’s own personality, drive and influence saw the Cistercians growing from a slightly quirky fringe monastic institution to being arguably the most significant component of Christian monasticism that the Middle Ages ever knew.

In addition to this St Bernard consorted with Princes, Kings and Pontiffs, even directly ‘creating’ his own Pope, BERNARDO PAGANELLI DI MONTEMAGNO (Eugnius III) who became Pontiff in 1145. This man had been a noviciate of St Bernard at Clairvaux and was, in all respects, St Bernard’s own man. From this point barely a decision was made in Rome that was not influenced in some way by St Bernard himself.

Much could be written about the ‘nature’ of St Bernard. He was a staunch supporter of the Virgin Mary, a visionary and a man who had a profound belief in an early and very ‘Culdean’ form of Christianity. This is exemplified by the short verse he once wrote.

‘Believe me, for I know, you will find something far greater in the woods than in books. Stones and trees will teach you that which you cannot learn from the masters.’

St Bernard staunchly supported what amounted to an utter veneration of the Virgin Mary for the whole of his life and was also an enthusiastic supporter of a rather strange little extract from the Old Testament, entitled ‘Solomon’s Song of Songs’.

How and why St Bernard became involved in the formation of the Knights Templar may never be fully understood. There is no doubt that he was blood-tied to some of the first Templar Knights, in particular Andre de Montbard, who was his maternal uncle. He may also have been related to the Counts of Champagne, who themselves appear to have been pivotal in the formation of the Templar Order.

For whatever reason St Bernard wrote the first ‘rules’ of the Templar Order. He may have undertaken this task personally and they were based, almost entirely, on the Order adopted by the Cistercians themselves. The Templars were officially declared to be a monastic order under the protection of Church in Troyes in 1139. Bernard went further and insisted that Pope Innocent II recognised this infant order as being solely under the authority of the Pope and no other temporal or ecclesiastical authority. It is a fact that the Templars venerated St Bernard from that moment on, until their own demise in 1307. St Bernard’s influence on the Templars is therefore pivotal to the whole of the movement’s aims and objectives and in our opinion no researcher should ever underestimate Bernard’s importance with this regard.

St Bernard travelled extensively, negotiated in civil disturbances and, surprisingly for the period, was instrumental in preventing a number of pogroms taking place against Jews in various locations within what is present day France. A staunch supporter of an Augustinian view of the mystery of the Christian faith, St Bernard was fiercely opposed to ‘rationalistic’ views of Christianity. In particular he was a staunch opponent of the dialectician ‘Peter Abelard’, a man whom St Bernard virtually destroyed when Abelard refused to accept Bernard’s own criticism of his radical ideas.

Although travelling extensively on many and varied errands during his life, St Bernard always returned to his own abbey of Clairvaux, which it seems (to us at least) had been deliberately built in a location that allowed free travel in all directions. It is suggested that Clairvaux was peopled with all manner of scholars, some of whom may well have been Jewish scribes. It is also true to say that if Citeaux remained the ‘head’ of the Cistercian movement during the life of St Bernard, Clairvaux lay at its heart. Clairvaux became the Mother House of many new Cistercian monasteries, not least of all Fountaines Abbey in Yorkshire, England, which itself was to rise to the rank of most prosperous abbey on English soil.

St Bernard died in Clairvaux on August 20th 1153, a date that would soon become his feast day, for St Bernard was canonised within a few short years of his death. Space here does not permit a full handling of this extraordinary man’s life or his interest in so many subjects, including architecture, music and (probably) ancient manuscripts. After his death a cult of St Bernard rapidly developed. At the time of the French Revolution St Bernard’s skull was taken for safekeeping to Switzerland, eventually finding its way back to Troyes. It is now housed in the Treasury of Troyes Cathedral and can be seen there, together with the skull and thighbone of St Malachy, a friend and contemporary of St Bernard.

A much fuller and more comprehensive detailed biography of St Bernard’s life can be found in ‘The Knights Templar Revealed’ Butler and Dafoe, Constable and Robinson – 2006.

About Us

TemplarHistory.com was started in the fall of 1997 by Stephen Dafoe, a Canadian author who has written several books on the Templars and related subjects.

Read more from our Templar History Archives – Templar History

|

|

|

|

|

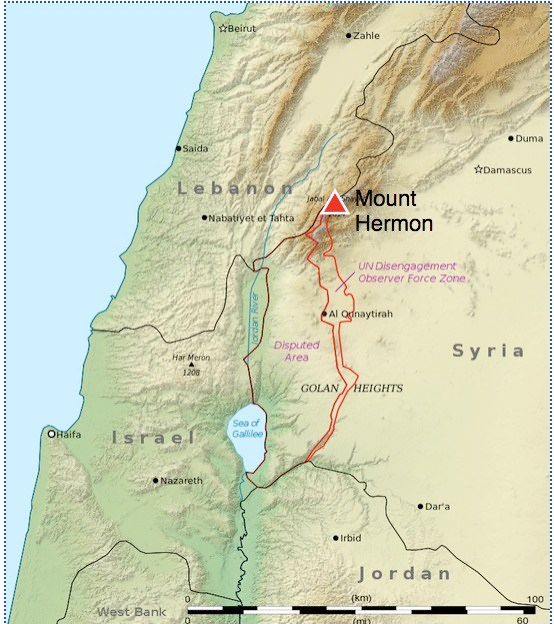

New International VersionIt is as if the dew of Hermon were falling on Mount Zion. For there the LORD bestows his blessing, even life forevermore.

New Living TranslationHarmony is as refreshing as the dew from Mount Hermon that falls on the mountains of Zion. And there the LORD has pronounced his blessing, even life everlasting.

English Standard VersionIt is like the dew of Hermon, which falls on the mountains of Zion! For there the LORD has commanded the blessing, life forevermore.

Berean Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion. For there the LORD has bestowed the blessing of life forevermore.

King James BibleAs the dew of Hermon, and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion: for there the LORD commanded the blessing, even life for evermore.

New King James VersionIt is like the dew of Hermon, Descending upon the mountains of Zion; For there the LORD commanded the blessing— Life forevermore.

New American Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon Coming down upon the mountains of Zion; For the LORD commanded the blessing there—life forever.

NASB 1995It is like the dew of Hermon Coming down upon the mountains of Zion; For there the LORD commanded the blessing— life forever.

NASB 1977It is like the dew of Hermon, Coming down upon the mountains of Zion; For there the LORD commanded the blessing—life forever.

Legacy Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon Coming down upon the mountains of Zion; For there, Yahweh commanded the blessing—life forever.

Amplified BibleIt is like the dew of [Mount] Hermon Coming down on the hills of Zion; For there the LORD has commanded the blessing: life forevermore.

Christian Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion. For there the LORD has appointed the blessing — life forevermore.

Holman Christian Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion. For there the LORD has appointed the blessing— life forevermore.

American Standard VersionLike the dew of Hermon, That cometh down upon the mountains of Zion: For there Jehovah commanded the blessing, Even life for evermore.

Contemporary English VersionIt is like the dew from Mount Hermon, falling on Zion's mountains, where the LORD has promised to bless his people with life forevermore.

English Revised VersionLike the dew of Hermon, that cometh down upon the mountains of Zion: for there the LORD commanded the blessing, even life for evermore.

GOD'S WORD® TranslationIt is like dew on [Mount] Hermon, dew which comes down on Zion's mountains. That is where the LORD promised the blessing of eternal life.

Good News TranslationIt is like the dew on Mount Hermon, falling on the hills of Zion. That is where the LORD has promised his blessing--life that never ends.

International Standard VersionIt is like the dew of Hermon falling on Zion's mountains. For there the LORD commanded his blessing— life everlasting.

Majority Standard BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon falling on the mountains of Zion. For there the LORD has bestowed the blessing of life forevermore.

NET BibleIt is like the dew of Hermon, which flows down upon the hills of Zion. Indeed that is where the LORD has decreed a blessing will be available--eternal life.

New Heart English Biblelike the dew of Hermon, that comes down on the hills of Zion: for there the LORD gives the blessing, even life forevermore.

Webster's Bible TranslationAs the dew of Hermon, and as the dew that descended upon the mountains of Zion: for there the LORD commanded the blessing, even life for ever.

World English Biblelike the dew of Hermon, that comes down on the hills of Zion; for there Yahweh gives the blessing, even life forever more.

Literal Translations

Literal Standard VersionAs dew of Hermon—That comes down on hills of Zion, "" For there YHWH commanded the blessing—Life for all time!

Young's Literal TranslationAs dew of Hermon -- That cometh down on hills of Zion, For there Jehovah commanded the blessing -- Life unto the age!

Smith's Literal TranslationAs the dew of Hermon coming down upon the mountains of Zion: for there Jehovah commanded the blessing, life even forever.

Catholic Translations

Douay-Rheims Bibleas the dew of Hermon, which descendeth upon mount Sion. For there the Lord hath commandeth blessing, and life for evermore.

Catholic Public Domain VersionIt is like the dew of Hermon, which descended from mount Zion. For in that place, the Lord has commanded a blessing, and life, even unto eternity.

New American BibleLike dew of Hermon coming down upon the mountains of Zion. There the LORD has decreed a blessing, life for evermore!

New Revised Standard VersionIt is like the dew of Hermon, which falls on the mountains of Zion. For there the LORD ordained his blessing, life forevermore.

Translations from Aramaic

Lamsa BibleLike the dew of Hermon that falls upon the mount of Zion; for there the LORD commanded the blessing, even life for evermore.

Peshitta Holy Bible TranslatedLike the dew of Hermon that descends upon the mountain of Zion, because there LORD JEHOVAH commanded the blessing and the Life unto eternity.

OT Translations

JPS Tanakh 1917Like the dew of Hermon, That cometh down upon the mountains of Zion; For there the LORD commanded the blessing, Even life for ever.

Brenton Septuagint TranslationAs the dew of Aermon, that comes down on the mountains of Sion: for there, the Lord commanded the blessing, even life for ever.

Additional Translations ...

|

|

|

|

|

|

Marie Madeleine d'Houët Feast Day

on the occasion of Marie Madeleine’s Feast Day, April 5th, 2022

Dear Sisters and Companions in Mission,

Once again, it is Marie Madeleine’s Feast Day, with its opportunity to express gratitude for the life of this saintly woman. Further, the celebration of her response to God’s call gives us an opening – if we need it, to pray for the suffering people of Ukraine and Myanmar.

Marie Madeleine was no stranger to the atrocities of revolution and war and there is an episode in her life that is worth deeper reflection. We are familiar with the story, but I invite us to look at it with fresh eyes, savouring the detail as an Ignatian prayer.

In ‘God’s Faithful Instrument’, Patricia Grogan fcJ, writes that ‘In January 1809 the inhabitants of Bourges watched, aghast, the long convoys of Spanish prisoners arriving from the frontier and filling the hospitals of the town. For the last ten years Napoleon had been marching from one victory to another, upsetting dynasties, changing the map of Europe, and placing his relatives on vacant thrones. In this last campaign England, Austria and Prussia had experienced defeat. French armies had penetrated Italy, Dalmatia, Poland, Denmark, and Portugal.

At home in France the population had long since become weary of war. Few were the families that had been spared the death or wounding of a father, son or brother. With the occupation of the Papal States, the Pope arrested and carried off into captivity, the Church was facing yet another period of persecution. The war in Spain was reported to be more tragic than elsewhere. It was there the picked French troops met their first set-back, repulsed by a population heroic to the degree of fanaticism. While the youth of France were being drafted in thousands to the frontier, convoys of prisoners who had escaped death, limped to the camps and hospitals of central France. With horror and fear the citizens of Bourges saw them come. Exhausted, wounded, even mutilated, many were ill with typhus. Bound together behind army carts, they were dragged rather than led. The local population for the most part could only see in them the implacable enemy that had inflicted atrocities on the French troops.

At a loss as to whom to appoint to care for the unfortunate prisoners, the Imperial Army appealed to the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. The Revolution had sadly diminished their ranks. Most of the available sisters were already serving in camps and hospitals nearer the frontier. The few who remained in Bourges needed assistance.

Marie Madeleine Victoire’s decision was soon made. Under the pretext of absenting herself on business, she slipped away. In the guise of a peasant woman and assuming a false name, she offered herself as an assistant at one of the hospitals. Accepted as an unknown woman, undoubtedly a generous one but lacking professional expertise, the tasks assigned to her were the lowliest. Victoire responded simply, giving of her best, struggling against sheer physical fatigue and the thought of Eugene, who, to her feverish mind, seemed to be calling her away. On the ninth day she succumbed to fever and exhaustion and asked to be taken to Parassy. Once there, Victoire sent for her sister, Angèle.’ (Pages 30 and 31)

Victoire was at death’s door with cholera, and we know that before falling unconscious she confided her son to Angèle, indicated where there was money for the poor, and made a general confession. A Sister of Charity - who had worked with Victoire in the hospital, died of the cholera. For Victoire’s family, there were long weeks of suspense, with nights of deep anxiety and on the fifteenth day hope gave way to relief when the patient regained consciousness and began to recover.

Reflecting on this episode, one might ask was it a responsible decision for the mother of a four-year-old child to even offer to serve in such a dangerous situation? … Was it an impetuous decision?

We can’t answer these questions and can only note that several people, including her sister, admired Victoire’s incredible courage and that her choice triggered nothing but good in her family. Family friends noted the change in the tenor of life in the de Bengy household. In fact, her gesture in favour of the stricken Spanish soldiers – who were prisoners of war, sharpened the family’s social conscience and marked a turning point in Victoire’s life.

So, dear FCJ Sisters and Companions in Mission, as we see the victims of war, whether refugees or soldiers, let us ask Marie Madeleine to pray with us for the grace to discern well, and for the courage to make choices that will widen the ‘Circle of Love’ - even when it involves risk. We beg her too, to pray with us for a conversion of heart for all world leaders.

May we celebrate the life of our Foundress, Marie Madeleine, with joy and deep gratitude.

With all blessings and in companionship,

Vice-Postulator for the Cause of Marie Madeleine

https://www.fcjcentre.ca/post/marie-madeleine-d-hou%C3%ABt-feast-day |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

3 a 17 de 17

Siguiente Anterior

3 a 17 de 17

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|

:quality(85)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/infobae/NYOFE4SO2JCGHF6IIT6EMBXGXI.jpg)

![Regreso Al Fururo III (Back To The Future III) [1990] –, 40% OFF](https://m.media-amazon.com/images/M/MV5BYzgzMDc2YjQtOWM1OS00ZjhhLWJiNjQtMzE3ZTY4MTZiY2ViXkEyXkFqcGdeQXVyNDQ0MTYzMDA@._V1_.jpg)

![Revelation 1:14 (lsv) - and His head and hairs [were] white, as if ...](https://img2.bibliaya.com/Bibleya/verse/revelation-1-14-lsv.jpg)