|

|

General: VEZELAY FRANCE MARY MAGDALENE/MARIE MADELEINE ASTRONOMICAL ALIGNMENT

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

Vézelay Abbey

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vézelay Abbey (French: Abbaye Sainte-Marie-Madeleine de Vézelay) is a Benedictine and Cluniac monastery in Vézelay in the east-central French department of Yonne. It was constructed between 1120 and 1150. The Benedictine abbey church, now the Basilica of Sainte-Marie-Madeleine (Saint Mary Magdalene), with its complex program of imagery in sculpted capitals and portals, is one of the great masterpieces of Burgundian Romanesque art and architecture.[1] Sacked by the Huguenots in 1569, the building suffered neglect in the 17th and the 18th centuries and some further damage during the period of the French Revolution.[2]

The church and hill at Vézelay were added to the UNESCO list of World Heritage Sites in 1979 because of their importance in medieval Christianity and outstanding architecture.[1]

Relics of Mary Magdalene can be seen inside the Basilica.

History[edit]

The Benedictine abbey of Vézelay was founded,[3] as many abbeys were, on land that had been a late Roman villa, of Vercellus (Vercelle becoming Vézelay). The villa had passed into the hands of the Carolingians and devolved to a Carolingian count, Girart, of Roussillon. The two convents he founded there were looted and dispersed by Moorish raiding parties in the 8th century, and a hilltop convent was burnt by Norman raiders. In the 9th century, the abbey was refounded under the guidance of Badilo, who became an affiliate of the reformed Benedictine order of Cluny. Vézelay also stood at the beginning of one of the four major routes through France for pilgrims going to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, in the north-western corner of Spain.

About 1050 the monks of Vézelay began to claim to hold the relics of Mary Magdalene, brought, they said, from the Holy Land either by their 9th-century founder-saint, Badilo, or by envoys despatched by him.[4] A little later a monk of Vézelay declared that he had detected in a crypt at St-Maximin in Provence, carved on an empty sarcophagus, a representation of the Unction at Bethany, when Jesus' head was anointed by Mary of Bethany, who was assumed in the Middle Ages to be Mary Magdalene. The monks of Vézelay pronounced this to be Mary Magdalene's tomb, from which her relics had been translated to their abbey. Freed captives then brought their chains as votive objects to the abbey, and it was the newly elected Abbot Geoffroy in 1037 who had the ironwork melted down and reforged as wrought iron railings surrounding the Magdalene's altar.[4] Thus the erection of one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture which followed was made possible by pilgrims to the declared relics and these tactile examples demonstrating the efficacy of prayers. Mary Magdalene is the prototype of the penitent, and Vézelay has remained an important place of pilgrimage for the Catholic faithful, though the actual claimed relics were torched by Huguenots in the 16th century.

Floorplan of Vézelay shows the adjustment in vaulting between the choir and the new nave.

To accommodate the influx of pilgrims a new abbey church was begun, dedicated on April 21, 1104, but the expense of building so increased the tax burden on the abbey's lands that the peasants rose up and killed the abbot. The crush of pilgrims was such that an extended narthex (an enclosed porch) was built, inaugurated by Pope Innocent II in 1132, to help accommodate the pilgrim throng.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux preached at Vézelay in favor of a second crusade at Easter 1146, in front of King Louis VII. Richard I of England and Philip II of France met there and spent three months at the Abbey in 1190 before leaving for the Third Crusade. Thomas Becket, in exile, chose Vézelay for his Whitsunday sermon in 1166, announcing the excommunication of the main supporters of his English King, Henry II, and threatening the King with excommunication too. The nave, which had been burnt once, with great loss of life, burned again in 1165, after which it was rebuilt in its present form.

The abbey's self-assured monastic community was prepared to defend its liberties and privileges against all comers:[5] the bishops of Autun, who challenged its claims to exemption; the counts of Nevers, who claimed jurisdiction in their court and rights of hospitality at Vézelay; the abbey of Cluny, which had reformed its rule and sought to maintain control of the abbot within its hierarchy; the townsmen of Vézelay, who demanded a modicum of communal self-government.

The beginning of Vézelay's decline coincided with the well-publicized discovery in 1279 of the body of Mary Magdalene at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume in Provence, given regal patronage by Charles II, the Angevin king of Sicily. When Charles erected a Dominican convent at La Sainte-Baume, the shrine was found intact, with an explanatory inscription stating why the relics had been hidden. The local Dominican friars compiled an account of miracles that these relics had wrought. This discovery undermined Vézelay's position as the principal shrine of the Magdalene in Europe.

After the Revolution, Vézelay stood in danger of collapse. In 1834 the newly appointed French inspector of historical monuments, Prosper Mérimée (more familiar as the author of Carmen), warned that it was about to collapse, and on his recommendation the young architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was appointed to supervise a massive and successful restoration, undertaken in several stages between 1840 and 1861, during which his team replaced a great deal of the weathered and vandalized sculpture. The flying buttresses that support the nave are his.[6]

Interpretation of the tympanum[edit]

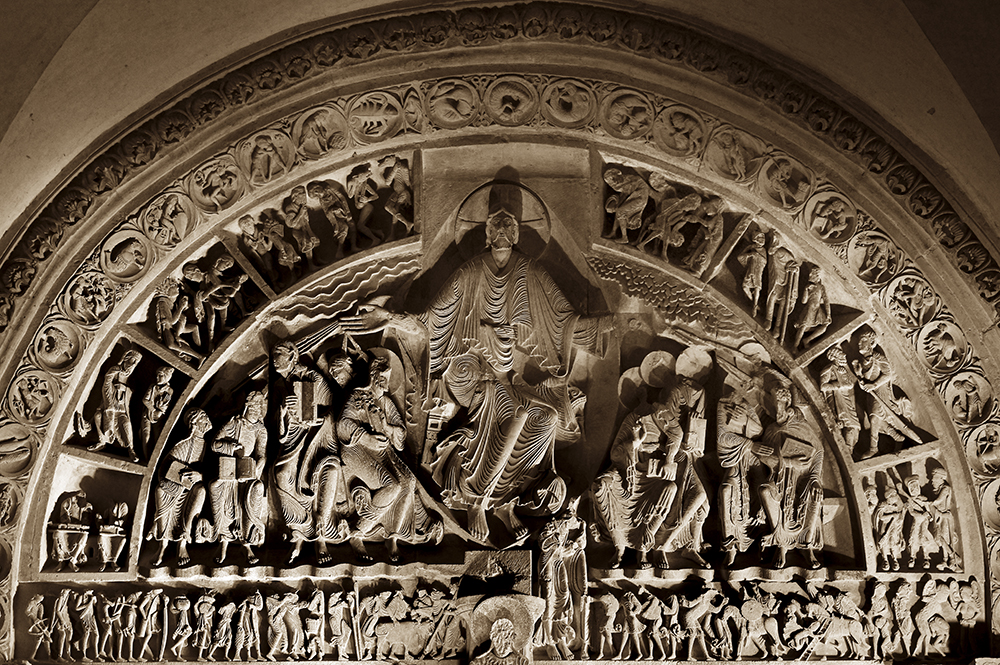

The tympanum of the central portal of the Madeleine de Vézelay is different from its counterparts across Europe. From the beginning, its tympanum was specifically designed to function as a spiritual defense of the Crusades and to portray a Christian allegory to the Crusaders' mission. When compared to contemporary churches such as St. Lazare d'Autun and St. Pierre de Moissac, the distinctiveness of Vézelay becomes apparent.

The art historian George Zarnecki wrote, "To most people the term Romanesque sculpture brings to mind a large church portal, dominated by a tympanum carved with an apocalyptic vision, usually the Last Judgment."[7] This is true in most cases, but Vézelay is an exception. In a 1944 article, Adolf Katzenellenbogen interpreted Vézelay's tympanum as referring to the First Crusade and depicting the Pentecostal mission of the Apostles.[8]

Thirty years before the Vézelay tympanum was carved, Pope Urban II planned on announcing his call for a crusade at La Madeleine[citation needed]. In 1095, Urban altered his plans and preached for the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont, but Vézelay remained a central figure in the history of the crusades. The tympanum was completed in 1130. Fifteen years after its completion, Bernard of Clairvaux chose Vézelay as the place from which he would call for a Second Crusade. Vézelay was even the staging point for the Third Crusade. It is there that King Richard the Lionheart of England and King Philip Augustus of France met and joined their armies for a combined western invasion of the holy land. It is appropriate, therefore, that Vézelay's portal reflect its place in the history of the crusades.

The art historian Peter Low argues for the central tympanum as a visualization of both the Pentecost and a passage from book of Ephesians chapter 2—proclaiming to the visiting laity the tenets of Benedictine monasticism and to visiting pilgrims the extent and reach of a universalizing church that welcomes "the full, even monstrous range of the globe's inhabitants."[9]

Detail of right side

The lintel of the Vézelay portal portrays the "ungodly" people of the world. It is a depiction of the first Pentecostal Mission to spread the word of God to all the people of the world. The figures in the tympanum who have not received the Word of God are depicted as not fully human. Some are shown with pig snouts, others are misshapen, and several are depicted as dwarves. One pygmy in particular is depicted as mounting a horse with the assistance of a ladder. On the far right, there is a man with elephantine ears, while in the center we see a man covered in feathers. The architects and artisans depicted the unbelievers as physically grotesque in order to provide a visual image of what they saw as the non-believers' moral turpitude. This is a direct reflection of Western perceptions of foreigners such as the Moors, who were being specifically targeted by the Crusaders. Even Pope Urban II, in his call for a crusade, helped promote this ethnocentric perception of the Turks by calling on westerners to, "exterminate this vile race."[10] Most Westerners had absolutely no idea what the Turks and Muslims looked like, and they assumed that an absence of Christianity must coincide with repulsive physical attributes. It has also been argued that the disbelievers were carved as deformed monsters in an effort to dehumanize them. By dehumanizing their enemies in art, the Crusaders' mission to capture the holy land and convert or kill the Muslims was glorified and sanctified. The Vézelay lintel is, therefore, a political statement as well as a religious one.

Lower compartments[edit]

Detail of centre

The lower four compartments of the Vézelay tympanum show the nations that had already received the Gospels. They include the Byzantines, Armenians, and Ethiopians. The inclusion of the Byzantines is particularly important because it was the Byzantines who initially requested a Crusade to the holy land. The Byzantines had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuk Turks through warfare, and they were eager to seek western military support to reclaim that territory.

The characters in the lower Vézelay compartments are regal and well proportioned. They are a direct contrast to their "heathen" counterparts in the lintel. They are human as opposed to monstrous. In the eyes of the designers, they had received God's grace and are thus pictured as fully human in every detail. These compartments can, therefore, can be seen as an allegory for the crusading nations. The Crusader armies were made up of many different nationalities bound only by faith in the same God. Nations that had previously warred with one another were suddenly united for a common goal. The lower tympanum compartments are an expression of this newfound solidarity.

Central portal[edit]

The central portal

The central portion of the Vézelay tympanum continues this process of politicizing religion. The central tympanum shows a benevolent Christ conveying his message to the Apostles, who flank him on either side. This Christ is distinct in Romanesque architecture. He is a stark contrast to the angry Christ of the St. Pierre de Moissac tympanum. The Moissac Christ is a forbidding figure that sits upon the throne of judgment. It is another example of the typical Romanesque Christ. His face is without caring or emotion. He holds the scrolls containing the deeds of mankind, and he stands ready to execute punishment on the damned. The Vézelay Christ, however, is pictured contraposto with arms wide. He is delivering a message, not exacting punishment. The Vézelay tympanum is remarkable because it is so different. The Vézelay Christ is sending the Crusaders out—he is not judging them. Indeed, the Crusaders were guaranteed remission of all sins if they participated in the Crusades. A forbidding Christ placed upon the throne of judgment would have been out of place at Vézelay. That is why the traditional Romanesque Christ, with its angry stare, was replaced at Vézelay by a kind and welcoming Christ with arms wide open.

Astronomical alignment[edit]

Looking east through nave on 23 June 1976, two days after the summer solstice  Mary Magdalene's relics in the crypt

In 1976, Hugues Delautre, one of the Franciscan fathers charged with stewardship of the Vézelay sanctuary, discovered that beyond the customary east-west orientation of the structure, the architecture of La Madeleine incorporates the relative positions of the Earth and the Sun into its design. Every June, just before the feast day of Saint John the Baptist, the astronomical dimensions of the church are revealed as the sun reaches its highest point of the year, at local noon on the summer solstice, when the sunlight coming through the southern clerestory windows casts a series of illuminated spots precisely along the longitudinal center of the nave floor.[13][14][15][16][17]

See also[edit]

|

|

|

|

|

MAGDALENE MATTERS

The Basilica Mary Magdalene of Vezelay

World Heritage Site in Burgundy, France.

In 2008, while working at the “Ateliers de scénographie des Forges” in Southern Burgundy I was called by clients for whom we had designed the scenography of the Visitor Centre in Vezelay, a Unesco designated World Heritage Site near Chablis. They asked if I would lead a tour in English for the Australian New South Wales Premier, Bob Carr. I did so and was struck by the degree to which he was bowled over by his experience. “I have visited the 7 wonders of the world but this is unique”, he said. Since then, I’ve become a heritage guide and a member of the Board of Governors of the association “Présence of Vézelay” that runs the Visitor Centre, a decision I have never regretted.

The 12th century abbey church, known today as the Basilica, is a masterpiece of Romanesque art. But what makes it unique worldwide is the exceptional play of light with the stone. The abbey’s history gives us the key to understanding this.

The foundation of the monastery dates back to 867. Initially a nunnery situated alongside the river Cure in the valley a mile below Vezelay, it was destroyed by the Normans six years later. It then became a monastery and the monks moved up the hill to the present site.

At its apogee Vezelay was to become a thriving medieval city with a population supposedly 10,000 strong, equivalent to London at the same time. It owes its importance to the presence, allegedly, of Mary Magdalene’s relics. Her story of transformation from sinner to first witness of the resurrection is a source of hope for Christians. As Europe was predominantly Christian at the time and pilgrimage was in full flow, Vezelay became one of the four gates in France opening onto the via lemovicensis pilgrim path to Santiago de Compostella.

The Great Tympanum, The Basilica Mary Magdalene of Vezelay.

The growing numbers of pilgrims at the beginning of the 12th century made a bigger abbey church necessary. To pay for it local taxes were increased. Tension with the inhabitants of the city grew and culminated in 1106 with a group forcing their way into the monastery and the abbot’s murder. Two monks are also reported to have killed a peasant in the same period. Faced with such a delicate situation the new abbot sought appeasement. The monastic community designed a new church highlighting Mary Magdalene’s story from shadow to light and the capacity for personal transformation possible for all, be they pilgrim, monk or inhabitant of the city.

The recurrent theme in the sculpture of the Basilica is transformation and not condemnation. The Great Tympanum at the entrance depicts Christ with his arms wide open at a time when last judgments were commonplace. The iconographic programme of 153 capitals focuses on the intimate struggles of the human heart, hence their universal significance so pertinent for visitors to this day.

Many great civilisations have left us with remarkable examples of the art of building with light, most of which are connected to or assimilated with notions of the divine such as Stonehenge or the Egyptian pyramids. The Basilica also bears witness to the art of creating dialogue with sunlight – for the Romanesque builders the sun was a way of symbolizing Christ. He is the light who comes to encounter humanity. The abbey church itself built of stone was to become an image of that meeting. When the rays of sunlight touch the stone and the stone resounds to the clarity of that light, there appears to be something like a conversation between stone and sun. This exchange is a way of symbolizing the dialogue between creation and Creator, between man and God, between the Christian and Christ.

Summer Solstice path of light, The Basilica Mary Magdalene of Vezelay.

At midday solar time on the 24th June, when the sun is at its highest, a path of nine pools of light runs down the centre of the nave to celebrate the feast of the prophet John the Baptist. Situated at the entrance to the nave, he indicates the path to the one who says, “I am the path, truth, life”, the words of Christ symbolized by the altar.

Winter solstice light, The Basilica Mary Magdalene of Vezelay.

At Christmas the sun on its lowest path lights up the capitals on the South facing side, representing the divine light coming to encounter humanity’s darker nights. From then on each day is longer – “Light shone in the darkness, darkness could not overcome it” (Jn 1,5).

At Eastertide the morning light blazes down the centre of the church from the choir windows down to the entrance doors, symbolizing the light of the resurrection announced by Mary Magdalene.

The "Madeleine", a popular name for the Basilica, and Magdalene College have in common their Benedictine origins. The Benedictine genius experienced by many a visitor here in Vezelay is to make the experience of “enlightenment” a very earthly process. It was also my experience while a student at Magdalene, thanks largely to my tutor. May that tradition continue today!

By Mr Christopher Kelly (1979)

This article was first published in Magdalene Matters Spring/Summer 2022 Issue 53.

|

|

|

|

|

The Benedictine abbey of Vézelay was founded,[3] as many abbeys were, on land that had been a late Roman villa, of Vercellus (Vercelle becoming Vézelay). The villa had passed into the hands of the Carolingians and devolved to a Carolingian count, Girart, of Roussillon. The two convents he founded there were looted and dispersed by Moorish raiding parties in the 8th century, and a hilltop convent was burnt by Norman raiders. In the 9th century, the abbey was refounded under the guidance of Badilo, who became an affiliate of the reformed Benedictine order of Cluny. Vézelay also stood at the beginning of one of the four major routes through France for pilgrims going to Santiago de Compostela in Galicia, in the north-western corner of Spain.

About 1050 the monks of Vézelay began to claim to hold the relics of Mary Magdalene, brought, they said, from the Holy Land either by their 9th-century founder-saint, Badilo, or by envoys despatched by him.[4] A little later a monk of Vézelay declared that he had detected in a crypt at St-Maximin in Provence, carved on an empty sarcophagus, a representation of the Unction at Bethany, when Jesus' head was anointed by Mary of Bethany, who was assumed in the Middle Ages to be Mary Magdalene. The monks of Vézelay pronounced this to be Mary Magdalene's tomb, from which her relics had been translated to their abbey. Freed captives then brought their chains as votive objects to the abbey, and it was the newly elected Abbot Geoffroy in 1037 who had the ironwork melted down and reforged as wrought iron railings surrounding the Magdalene's altar.[4] Thus the erection of one of the finest examples of Romanesque architecture which followed was made possible by pilgrims to the declared relics and these tactile examples demonstrating the efficacy of prayers. Mary Magdalene is the prototype of the penitent, and Vézelay has remained an important place of pilgrimage for the Catholic faithful, though the actual claimed relics were torched by Huguenots in the 16th century.

Floorplan of Vézelay shows the adjustment in vaulting between the choir and the new nave.

To accommodate the influx of pilgrims a new abbey church was begun, dedicated on April 21, 1104, but the expense of building so increased the tax burden on the abbey's lands that the peasants rose up and killed the abbot. The crush of pilgrims was such that an extended narthex (an enclosed porch) was built, inaugurated by Pope Innocent II in 1132, to help accommodate the pilgrim throng.

Saint Bernard of Clairvaux preached at Vézelay in favor of a second crusade at Easter 1146, in front of King Louis VII. Richard I of England and Philip II of France met there and spent three months at the Abbey in 1190 before leaving for the Third Crusade. Thomas Becket, in exile, chose Vézelay for his Whitsunday sermon in 1166, announcing the excommunication of the main supporters of his English King, Henry II, and threatening the King with excommunication too. The nave, which had been burnt once, with great loss of life, burned again in 1165, after which it was rebuilt in its present form.

The abbey's self-assured monastic community was prepared to defend its liberties and privileges against all comers:[5] the bishops of Autun, who challenged its claims to exemption; the counts of Nevers, who claimed jurisdiction in their court and rights of hospitality at Vézelay; the abbey of Cluny, which had reformed its rule and sought to maintain control of the abbot within its hierarchy; the townsmen of Vézelay, who demanded a modicum of communal self-government.

The beginning of Vézelay's decline coincided with the well-publicized discovery in 1279 of the body of Mary Magdalene at Saint-Maximin-la-Sainte-Baume in Provence, given regal patronage by Charles II, the Angevin king of Sicily. When Charles erected a Dominican convent at La Sainte-Baume, the shrine was found intact, with an explanatory inscription stating why the relics had been hidden. The local Dominican friars compiled an account of miracles that these relics had wrought. This discovery undermined Vézelay's position as the principal shrine of the Magdalene in Europe.

After the Revolution, Vézelay stood in danger of collapse. In 1834 the newly appointed French inspector of historical monuments, Prosper Mérimée (more familiar as the author of Carmen), warned that it was about to collapse, and on his recommendation the young architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc was appointed to supervise a massive and successful restoration, undertaken in several stages between 1840 and 1861, during which his team replaced a great deal of the weathered and vandalized sculpture. The flying buttresses that support the nave are his.[6]

Interpretation of the tympanum[edit]

The tympanum of the central portal of the Madeleine de Vézelay is different from its counterparts across Europe. From the beginning, its tympanum was specifically designed to function as a spiritual defense of the Crusades and to portray a Christian allegory to the Crusaders' mission. When compared to contemporary churches such as St. Lazare d'Autun and St. Pierre de Moissac, the distinctiveness of Vézelay becomes apparent.

The art historian George Zarnecki wrote, "To most people the term Romanesque sculpture brings to mind a large church portal, dominated by a tympanum carved with an apocalyptic vision, usually the Last Judgment."[7] This is true in most cases, but Vézelay is an exception. In a 1944 article, Adolf Katzenellenbogen interpreted Vézelay's tympanum as referring to the First Crusade and depicting the Pentecostal mission of the Apostles.[8]

Thirty years before the Vézelay tympanum was carved, Pope Urban II planned on announcing his call for a crusade at La Madeleine[citation needed]. In 1095, Urban altered his plans and preached for the First Crusade at the Council of Clermont, but Vézelay remained a central figure in the history of the crusades. The tympanum was completed in 1130. Fifteen years after its completion, Bernard of Clairvaux chose Vézelay as the place from which he would call for a Second Crusade. Vézelay was even the staging point for the Third Crusade. It is there that King Richard the Lionheart of England and King Philip Augustus of France met and joined their armies for a combined western invasion of the holy land. It is appropriate, therefore, that Vézelay's portal reflect its place in the history of the crusades.

The art historian Peter Low argues for the central tympanum as a visualization of both the Pentecost and a passage from book of Ephesians chapter 2—proclaiming to the visiting laity the tenets of Benedictine monasticism and to visiting pilgrims the extent and reach of a universalizing church that welcomes "the full, even monstrous range of the globe's inhabitants."[9]

Detail of right side

The lintel of the Vézelay portal portrays the "ungodly" people of the world. It is a depiction of the first Pentecostal Mission to spread the word of God to all the people of the world. The figures in the tympanum who have not received the Word of God are depicted as not fully human. Some are shown with pig snouts, others are misshapen, and several are depicted as dwarves. One pygmy in particular is depicted as mounting a horse with the assistance of a ladder. On the far right, there is a man with elephantine ears, while in the center we see a man covered in feathers. The architects and artisans depicted the unbelievers as physically grotesque in order to provide a visual image of what they saw as the non-believers' moral turpitude. This is a direct reflection of Western perceptions of foreigners such as the Moors, who were being specifically targeted by the Crusaders. Even Pope Urban II, in his call for a crusade, helped promote this ethnocentric perception of the Turks by calling on westerners to, "exterminate this vile race."[10] Most Westerners had absolutely no idea what the Turks and Muslims looked like, and they assumed that an absence of Christianity must coincide with repulsive physical attributes. It has also been argued that the disbelievers were carved as deformed monsters in an effort to dehumanize them. By dehumanizing their enemies in art, the Crusaders' mission to capture the holy land and convert or kill the Muslims was glorified and sanctified. The Vézelay lintel is, therefore, a political statement as well as a religious one.

Comparison with other contemporary portals[edit]

Vézelay's political motivation becomes all the more apparent when compared with contemporary portal designs from other churches around France. The Vézelay lintel is distinct, but some comparisons can be made between it and other Romanesque portal sculptures of the time. Vézelay's lintel is comparable to the St. Lazare lintel in Autun in that both show humans who have sinned. While the Vézelay lintel is devoted to the depiction of "heathens," the Autun lintel shows the damned souls on Judgment Day. The similarity between both lintels is due in large part to the fact that the same master artisan, Master Gislebertus, was the primary architect on both sites. "Gislebertus ... began his career at Cluny, then worked on the original west facade at Vézelay, and c. 1120 moved to Autun."[11] In addition, the two tympana are similar in that they follow the tradition of placing the exaggerated Christ in the center of the image. Here is where the similarity stops, however. Autun is more traditional and typical of the Romanesque portal carvings. It depicts the Second Coming, which is a popular and typical depiction in Romanesque art. Frightful images of demons abound. The goals of the two different tympana are reflected in their design; Autun is designed to frighten people back to church while Vézelay is designed as a political statement to support the crusades.

Lower compartments[edit]

Detail of centre

The lower four compartments of the Vézelay tympanum show the nations that had already received the Gospels. They include the Byzantines, Armenians, and Ethiopians. The inclusion of the Byzantines is particularly important because it was the Byzantines who initially requested a Crusade to the holy land. The Byzantines had lost Jerusalem to the Seljuk Turks through warfare, and they were eager to seek western military support to reclaim that territory.

The characters in the lower Vézelay compartments are regal and well proportioned. They are a direct contrast to their "heathen" counterparts in the lintel. They are human as opposed to monstrous. In the eyes of the designers, they had received God's grace and are thus pictured as fully human in every detail. These compartments can, therefore, can be seen as an allegory for the crusading nations. The Crusader armies were made up of many different nationalities bound only by faith in the same God. Nations that had previously warred with one another were suddenly united for a common goal. The lower tympanum compartments are an expression of this newfound solidarity.

Upper compartments[edit]

While the lower four compartments represent the Christian nations, the upper four compartments are a representation of the second mission of the Apostles. According to the Bible, "many wonders and signs were done by the apostles."[12] These wonders included the healing of the sick and the casting out of demons and devils. These acts are represented in the upper four compartments of the Vézelay tympanum. In one compartment, a pair of lepers is shown with looks of astonishment as they compare limbs that have been miraculously healed. The demons are analogous to the non-Christians inhabiting the holy land. In reference to the Turkish take-over of the holy lands, Pope Urban said, "What a disgrace that a race so despicable, degenerate, and enslaved by demons should thus overcome a people endowed with faith in Almighty God!"[10] It is not difficult to see the parallel between the Apostles' mission of casting out demons, and the designer's view of the crusaders' mission of casting out "a race ... enslaved by demons." It is further evidence of the Vézelay portal's peculiar political motives.

Central portal[edit]

The central portal

The central portion of the Vézelay tympanum continues this process of politicizing religion. The central tympanum shows a benevolent Christ conveying his message to the Apostles, who flank him on either side. This Christ is distinct in Romanesque architecture. He is a stark contrast to the angry Christ of the St. Pierre de Moissac tympanum. The Moissac Christ is a forbidding figure that sits upon the throne of judgment. It is another example of the typical Romanesque Christ. His face is without caring or emotion. He holds the scrolls containing the deeds of mankind, and he stands ready to execute punishment on the damned. The Vézelay Christ, however, is pictured contraposto with arms wide. He is delivering a message, not exacting punishment. The Vézelay tympanum is remarkable because it is so different. The Vézelay Christ is sending the Crusaders out—he is not judging them. Indeed, the Crusaders were guaranteed remission of all sins if they participated in the Crusades. A forbidding Christ placed upon the throne of judgment would have been out of place at Vézelay. That is why the traditional Romanesque Christ, with its angry stare, was replaced at Vézelay by a kind and welcoming Christ with arms wide open.

Astronomical alignment[edit]

Looking east through nave on 23 June 1976, two days after the summer solstice  Mary Magdalene's relics in the crypt

In 1976, Hugues Delautre, one of the Franciscan fathers charged with stewardship of the Vézelay sanctuary, discovered that beyond the customary east-west orientation of the structure, the architecture of La Madeleine incorporates the relative positions of the Earth and the Sun into its design. Every June, just before the feast day of Saint John the Baptist, the astronomical dimensions of the church are revealed as the sun reaches its highest point of the year, at local noon on the summer solstice, when the sunlight coming through the southern clerestory windows casts a series of illuminated spots precisely along the longitudinal center of the nave floor.[13][14][15][16][17]

|

|

|

Primer

Primer

Anterior

2 a 6 de 36

Siguiente

Anterior

2 a 6 de 36

Siguiente Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|