|

|

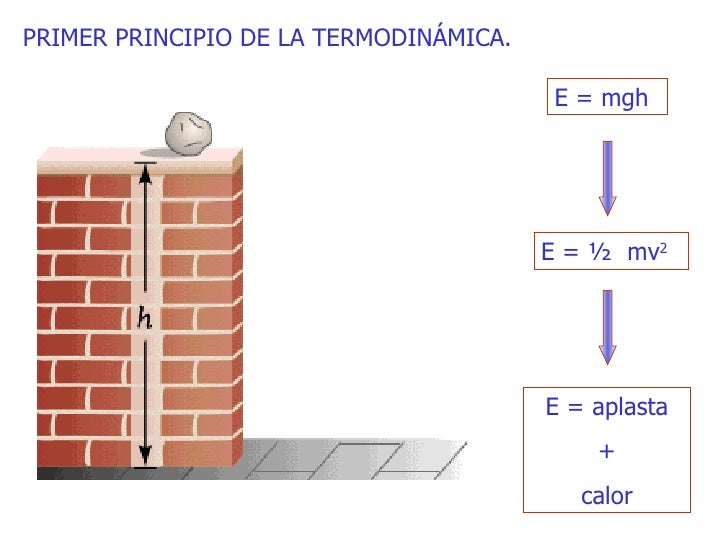

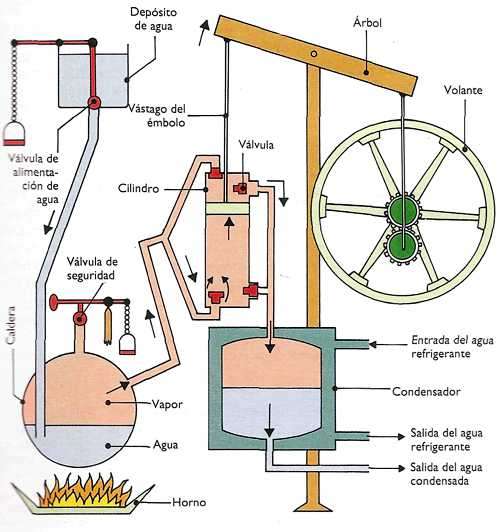

General: DOCTOR BROWN 1.21 GIGAWATTS GREAT SCOTT SCOTLAND/JAMES WATT/TRANSFIGURATION

Choisir un autre rubrique de messages |

|

Réponse |

Message 1 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 44 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 45 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Evidence the Knights Templar got to America!

The latest episode of Templar Knight TV looks at claims the Knights Templar got to America. It’s alleged they managed to do this a hundred years before Christopher Columbus reached the New World. But is there any truth to this?

The story starts with the Templars’ demise. It’s 1307 and they are being rounded up, imprisoned and some are burned to death. Little wonder some Knights Templar may have fled. A popular theory runs that when word got out that they were doomed, some knights transported treasure from the Paris Temple to the port of La Rochelle. From there, ships took the surviving Templars to Scotland. And then what happened?

Well, I was involved in a programme last year called America Unearthed presented by Scott Wolter. He is a forensic geologist and his analysis of rock carvings in the United States and Scotland has convinced him the knights made the long journey. With the help of a Scottish aristocrat called Henry Sinclair, they crossed the Atlantic to Nova Scotia.

As you will all know, proof that the Knights Templar got to America is offered in the form of items found at Oak Island in Nova Scotia; an enigmatic tower at Newport, Rhode Island and what is claimed to be the engraving of a knight in Westford, Massachusetts. But sceptics abound. They’re not convinced by the Money Pit at Oak Island, think the Newport Tower is a 17th century windmill and that the Westford Knight is a trick of the eye on a glacial boulder.

FIND OUT MORE: Did the Knights Templar take the Holy Grail to America?

As for the Sinclair connection, sceptics point out that these Scottish nobles testified against the Templars at their trial. Far from being good friends and allies of the knights, they had little sympathy and turned on them in their hour of need.

DISCOVER: The Westford Knight is disappearing!

Nevertheless, the argument rages on that the Knights Templar got to America. I go to Rosslyn chapel where some have pointed to images that look like maize – a crop that didn’t exist in the Old World before Columbus. And in the basement sacristy, lines on the wall are claimed to be a map. I had exclusive access when the chapel was empty to film for myself and you can see what I found.

I do hope you can spare a quarter of an hour to get your weekly Templar dose!

https://thetemplarknight.com/2020/09/15/knights-templar-america/ |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 46 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 47 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 48 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 49 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 50 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Our 26th President Teddy Roosevelt was a Freemason.

He is Honored with a Memorial in Washington D.C. on an Island in the Potomac River. The Island was once called "MY LORDS ISLAND" and was known as "MASON ISLAND".

An interesting alignment occurs when a map of Washington DC is viewed looking to the EAST...

Place two diagrams of the Great Pyramid (with slopes of 51.51) on the map of DC with their corners touching and resting on the Roosevelt Memorial on "MASON ISLAND" ---

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 51 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Our 26th President Teddy Roosevelt was a Freemason.

He is Honored with a Memorial in Washington D.C. on an Island in the Potomac River. The Island was once called "MY LORDS ISLAND" and was known as "MASON ISLAND".

An interesting alignment occurs when a map of Washington DC is viewed looking to the EAST...

Place two diagrams of the Great Pyramid (with slopes of 51.51) on the map of DC with their corners touching and resting on the Roosevelt Memorial on "MASON ISLAND" ---

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 52 de 58 de ce thème |

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 53 de 58 de ce thème |

|

-AA+A

1911–1915, John Russell Pope. 1733 16th St. NW

(Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress)

Scottish Rite Temple (Franz Jantzen)

☰ SEE METADATA

The mausoleum at Halikarnassos (353–c. 340 b.c.e.) was a model for many buildings in this period, including Masonic temples, because as one of the seven wonders of the ancient world it was associated with the beginnings of Western architectural traditions. The origins of freemasonry are linked to the lodges of medieval stonemasons and with a practice of architecture based on fundamental rules of the universe, with its most esoteric aspects expressed through a language of symbols. The definition of freemasonry as “a peculiar system of morality, veiled in allegory, and illustrated by symbols” explains why the buildings housing such organizations are themselves expressive of symbolic meaning.

Thrown down by an earthquake in the thirteenth century and quarried in the sixteenth century by the Knights of Saint John for the building of one of their castles, King Mausolos's tomb, a Hellenistic monument located on the Turkish coast, was the subject of numerous reconstructions by historians, archaeologists, and architects based on two ancient texts that describe its huge dimensions, colonnaded base, and stepped pyramidal top supporting a quadriga.

John Russell Pope's design, based on Newton and Pullman's 1862 restoration of the mausoleum, is centered on a nearly square site (217.5 by 212 feet) and raised above 16th Street on a podium with steps that extend the width of the block and that are organized according to arcane numerology. Three, five, seven, and nine steps converge on the central entry, which is guarded by Sphinxes, sculpted by Adolph A. Weinman, representing wisdom and power, contemplation and action. Thirty-six Ionic columns 33 feet high circumscribe the temple room, where the highest degree of freemasonry (the thirty-third) is conferred. The attic, marked by acroteria and the stepped pyramid, covers a square Guastavino dome; thus, the basic form above the base encloses a single volume. The compact base, with its expanses of smooth walls broken only by windows and doors, the peripteral colonnade set against nearly solid walls, and the faceted surfaces of the roof demonstrate Pope's unerring sense of balanced proportional relationships between masses and details. The light, monochromatic Indiana limestone is particularly well suited to the combination of planar surfaces and finely carved Greek and Egyptian details. Although Pope, with the advice of local architect and mason Elliott Woods, was responsible for incorporating some basic symbolism, the inscriptions and symbolic decorative details were planned by the grand commander of the lodge, George Fleming Moore, after the architectural design was completed.

The ground story is represented by the monolithic base on the exterior; on the interior an apsed atrium is ringed by offices, meeting rooms, banquet hall, and libraries. The atrium's form and decoration were intended as symbolic imitation of a Roman impluvium. Two sets of four massive Doric columns in a highly polished green Windsor, Vermont, granite establish a pathway leading to the apse on the east, where the main stair rises to the temple room. The oak-beam ceiling is painted in deep shades of red, brown, blue, yellow, and green, as are the walls in recesses behind the column screens. The decorative vocabulary mixes Greek frieze motifs and Egyptian hieroglyphics. The variation of rich and beautifully crafted materials continues in the main space. The temple room, a square with beveled corners that continue up into the dome, is constructed of limestone walls, Botticino marble dado, black and white marble floors, and a Guastavino tile dome. Windows are screened by Ionic columns set in antis made of green Windsor, Vermont, granite. Their gilded bronze capitals and bases echo the lavish use of gold or bronze in the entablature, windows, screens, and doors. The vault nearly doubles the height of the room, a proportional relationship that complements the subdued richness of the architectural surface. American architectural critic Aymar Embury so admired Pope's Scottish Rite Temple that he maintained, “Roman architects of two thousand years ago would prefer [it] to any of their own work.” 43

https://sah-archipedia.org/buildings/DC-01-MH12 |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 54 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Madeleine de France, Queen of Scotland, 1536

(Madeleine de France (1520-37) Queen of Scotland, 1536 )

|

https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Corneille-de-Lyon/80721/Madeleine-de-France,-Queen-of-Scotland,-1536.html |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 55 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Madeleine de France, Queen of Scotland, 1536

(Madeleine de France (1520-37) Queen of Scotland, 1536 )

|

https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Corneille-de-Lyon/80721/Madeleine-de-France,-Queen-of-Scotland,-1536.html |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 56 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Madeleine of Valois

Madeleine of Valois (10 August 1520 – 7 July 1537) was a French princess who briefly became Queen of Scotland in 1537 as the first wife of King James V. The marriage was arranged in accordance with the Treaty of Rouen, and they were married at Notre-Dame de Paris in January 1537, despite French reservations over her failing health. Madeleine died in July 1537, only six months after the wedding and less than two months after arriving in Scotland, resulting in her nickname, the "Summer Queen".

Madeleine (back right) with her mother and sisters, from the Book of Hours of Catherine de'Medici.

Madeleine was born at the Chteau de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France, the fifth child and third daughter of King Francis I of France and Claude, Duchess of Brittany, herself the eldest daughter of King Louis XII of France and Anne, Duchess of Brittany.

She was frail from birth, and grew up in the warm and temperate Loire Valley region of France, rather than at Paris, as her father feared that the cold would destroy her delicate health. Together with her sister, Margaret, she was raised by her aunt, Marguerite de Navarre until her father remarried and his new wife, Eleanor of Austria, took them into her own household.[1] By her sixteenth birthday, she had contracted tuberculosis.[2]

Marriage negotiations

[edit]

Three years before Madeleine's birth, the Franco-Scottish Treaty of Rouen was made to bolster the Auld Alliance after Scotland's defeat at the Battle of Flodden. A marriage between a French princess and the Scottish King was one of its provisions.[3] In April 1530, John Stewart, Duke of Albany, was appointed commissioner to finalize the royal marriage between James V and Madeleine.[4] However, as Madeleine did not enjoy good health, another French bride, Mary of Bourbon, was proposed.[5]

James V sent his herald James Atkinhead to see Mary of Bourbon,[6] and a contract was made for James to marry her. King James travelled to France in 1536 to meet Mary of Bourbon, but smitten with the delicate Madeleine, he asked Francis I for her hand in marriage. Fearing the harsh climate of Scotland would prove fatal to his daughter's already failing health, Francis I initially refused to permit the marriage.[7]

James V met Francis I and the French royal household between Roanne and Lyon on 13 October.[8] He continued to press Francis I for Madeleine's hand, and despite his reservations and nagging fears, Francis I reluctantly granted permission to the marriage only after Madeleine made her interest in marrying James very obvious. The court moved down the Loire Valley to Amboise, and to the Chteau de Blois, and the marriage contract was signed on 26 November 1536.[9]

Wedding at Notre-Dame

[edit]

Notre-Dame de Paris Notre-Dame de Paris and its environs, known as the Parvis, Jean Marot, 17th century

In preparation for the wedding, Francis I bought clothes and furnishings for Madeleine; jewels and gold chains were supplied by Regnault Danet, linen and cloths by Marie de Genevoise and Phillipe Savelon, clothes by the tailors Marceau Goursault and Charles Lacquait, veils by Jean Guesdon, and trimmings by Victor de Laval, who also made passementerie for a bed that Francis gave the couple. The goldsmith Thibault Hotman made silver plate for Madeleine.[10][11] The merchants of the royal "argenterie", René Tardif and Robert Fichepain supplied silks and woollen cloth.[12] A quantity of gold and silver trimmings for embroidering the clothes of Madeleine and her ladies were ordered from Baptiste Dalverge, a wire-drawer.[13] A platform walkway was constructed from the Bishop's Palace to Notre-Dame de Paris.[14]

After a Royal Entry into Paris on 31 December 1536,[15] they were married at Notre-Dame on 1 January 1537.[2] There was a banquet that night in the Great Hall of the Palais de la Cité.[16] Over the next two weeks there were further celebrations and tournaments at the Chteau de la Tournelle and Louvre.[17] The wedding festivities in 1537 were similar to those of 24 April 1558, for the wedding of Mary, Queen of Scots, and Francis, Dauphin of France.[18]

Francis I provided Madeleine with a generous dowry of 100,000 écu, and a further 30,000 francs settled on James V. According to the marriage contract made at Blois, Madeleine renounced her and any of her heirs' claims to the French throne. If James died first, Madeleine would retain for her lifetime assets including the Earldoms of Fife, Strathearn, Ross, and Orkney with Falkland Palace, Stirling Castle, and Dingwall Castle, with the Lordship of Galloway and Threave Castle.[19]

Coat of arms of Madeleine of Valois as Queen consort of Scots

In February the couple moved to Chantilly, to Senlis and Compiègne, where James received the Papal gift of hat and sword.[20][21][22] They stayed two nights at the Chteau de La Roche-Guyon.[23] After months of festivities and celebrations, the couple left France for Scotland from Le Havre in May 1537. The French ships were commanded by Jacques de Fountaines, Sieur de Mormoulins.[24] On 15 May, English sailors sold fish to the Scottish and French fleet off Bamburgh Head.[25] Madeleine's health deteriorated even further, and she was very sick when the royal pair landed in Scotland. They arrived at Leith at 10 o'clock on Whitsun-eve, 19 May 1537.[26]

According to John Lesley the ships were laden with her possessions;

"besides the Quenes Hienes furnitour, hinginis, and appareill, quhilk wes schippit at Newheavin and careit in Scotland, was also in hir awin cumpanye, transportit with hir majestie in Scotland, mony costlye jewells and goldin wark, precious stanis, orient pearle, maist excellent of any sort that was in Europe, and mony coistly abilyeaments for hir body, with mekill silver wark of coistlye cupbordis, cowpis, & plaite."[27]

A list or inventory of wedding presents from Francis I also survives, including Arras tapestry, cloths of estate, rich beds, two cupboards of silver gilt plate, table carpets, and Persian carpets.[28][29] Francis I also gave James V three of the ships, the Salamander, Morsicher, and Great Unicorn.[30] Madeleine took up residence at Holyrood Palace on 21 May 1537.[31]

French household in Scotland

[edit]

The French courtiers who came with her to Scotland to form her household included; her former governess, Anne de Boissy Gouffier, Madame de Montreuil; Anne de Viergnon, Madame de Bren or Bron; Anne Le Maye; Marguerite de Vergondois her chamberer; Marion Truffaut, her nurse; her secretary, Jean de Langeac, Bishop of Limoges; master household, Jean de St Aubin; squires and cupbearers Charles de Marconnay and Charles du Merlier; the physician Master Partix; pages John Crammy and Pierre de Ronsard; furrier Gillan; butcher John Kenneth; barber Anthony.[32][33][34] A physician from Paris, Jacques Lecoq, set out later to join her in Scotland.[35]

Madeleine wrote to her father from Edinburgh on 8 June 1537 saying that she was better and her symptoms had diminished. James V had written to Francis I asking him to send the physician Master Francisco, and Madeleine wrote that he was now needed only to perfect her cure. She signed this letter "Magdalene de France".[36] However, a month later, on 7 July 1537, (a month before her 17th birthday), Madeleine, the so-called "Summer Queen" of Scots, died in her husband's arms at Holyrood Palace.[37]

James V wrote to Francis I informing him of his daughter's death.[38] He called Madeleine "my dear companion" – votre fille, ma trés chére compaigne.[39]

Queen Madeleine was interred in Holyrood Abbey in Edinburgh, next to King James II of Scotland. Black mourning clothes were worn at her funeral, and an order was sent to the merchants of Dundee to provide black cloth. Her household servants were provided with "dule gowns", and horses at the procession had black cloths and trappings.[40][41] The chapel at Holyrood Palace was draped with cloth from Milan.[42] The grave was desecrated by a mob in 1776 and her allegedly still beautiful head was stolen.[43]

One of her gentlewomen, Madame de Montrueil or Motrell, visited London on her way back to France. She said that Madeleine "had no good days after her arrival there (in Scotland), but always sickly with a catarrh which descended into her stomach, which was the cause of her death".[44]

An inventory made of the king's goods in 1542 includes some of her clothes, furnishings for her chapel, six stools for her gentlewomen to sit upon, and gold cups and other items made for her when she was a child.[45]

Madeleine's marriage and death were commemorated by the poet David Lyndsay's Deploration of Deith of Quene Magdalene; the poem describes the pageantry of the marriage in France and Scotland:

O Paris! Of all citeis principall!

Quhilk did resave our prince with laud and glorie,

Solempnitlie, throw arkis triumphall. [arkis = arches]

* * * * * *

Thou mycht have sene the preparatioun

Maid be the Thre Estaitis of Scotland

In everilk ciete, castell, toure, and town

* * * * * *

Thow saw makand rycht costlie scaffalding

Depaynted weill with gold and asure fyne

* * * * * *

Disagysit folkis, lyke creaturis devyne,

On ilk scaffold to play ane syndrie storie

Bot all in greiting turnit thow that glorie. [greiting = crying: thow = death][46]

Epitaphs in Latin were composed by the French writers Etienne Dolet, Nicolas Desfrenes, Jean Visagier, and an anonymous poet. Gilles Corrozet and Pierre de Ronsard wrote verses in French.[47]

Less than a year after her death, following negotiations completed by David Beaton, James V married the widowed Mary of Guise. She had attended his wedding to Madeleine, and perhaps her uncle, Jean, Cardinal of Lorraine, suggested her to Francis I as a bride for the Scottish king.[48] Twenty years later, listed amongst the treasures in Edinburgh Castle were two little gold cups, an agate basin, a jasper vase, and crystal jug given to Madeleine when she was a child in France.[49]

|

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 57 de 58 de ce thème |

|

The tragic tale of Madeleine of Valois – the ‘Summer Queen of Scots’

7th August 2020

Madeleine of Valois was a French Princess who married James V King of Scots (The Scottish King had the title King of Scots rather than King of Scotland). The marriage was part of the Treaty of Rouen between Scotland and France. As part of that Treaty, James was promised the hand in marriage of a French Princess. Initially, James was contracted to marry another member of the French Royal Family. However, she didn’t appeal to him, and when he arrived at the French court, he wanted only Madeleine and the French King was convinced to allow their marriage to go ahead. Due to Madeleine’s poor health, the marriage would be a short one. She died only six months on from their wedding day. Because of her short time spent as Consort, she received the nickname the ‘Summer Queen of Scots’.

Madeleine was born in Saint-Germaine-en-Laye west of Paris on the 10 August 1520. She was the 5th child of Francis I, King of France and Claude Duchess of Brittany. Her health was fragile, and for that reason, the decision was made to raise her in the Loire Valley where the climate was more warm and temperate. Her mother died when she was three-years-old, and she was raised by her aunt, Marguerite of Navarre, until the remarriage of her father to Eleanor of Austria who accepted Madeleine into her household. By the time she was 16, Madeleine had developed Tuberculosis, the disease which probably took her mother’s life.

Madeleine of Valois Madeleine of Valois

In 1517, three years before Madeleine’s birth, the Treaty of Rouen was signed between France and Scotland. It was a treaty of mutual assistance if the English attacked either country. As part of that Treaty, the French King promised marriage between the Scottish King and one of his daughters. As King James V was only a five year old at the time of the Treaty the negotiations on the marriage did not begin until 1530. Madeleine was then the eldest living daughter. However, King Francis was concerned because of her fragile health she would not survive the harsh Scottish weather and it’s sometimes violent political climate. So he proposed an alternative bride from his extended family Marie of Bourbon who he would regard as a daughter and provide a dowry. In 1536 King James V travelled to France to meet his prospective bride, however on meeting Marie he was not impressed by her. He travelled to the French court, met Madeleine, and the two of them fell in love. They both persuaded King Francis to agree to the marriage which he eventually did. James and Madeleine were married in Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris on 1 January 1537. King Francis provided a very generous dowry which greatly bolstered the Scottish Treasury.

The wedding was followed by four months of festivities. It felt appropriate due to Madeleine’s health to delay their journey to Scotland until the Spring. They departed France in a fleet of 10 ships and arrived in Leith on 19 May 1537. Madeleine kissed the earth when she arrived in her husband’s kingdom. In preparation for her arrival, James ordered improvements to Falkland Palace and the Chapel Royal. He was also in the process of building new tennis courts and had added a tower built in a French style to Holyrood Palace. A coronation was also planned for Madeleine. However, her health suddenly deteriorated, and she died in the arms of James on 7 July 1537. She was a month short of her 17th birthday. She was buried with great pomp and ceremony in the Royal Chapel of Holyrood Abbey. A year later James married again to Marie of Guise the widowed Duchess of Longueville and a good friend of Madeleine. He would only outlive Madeleine by five years dying in 1542 age 30. Having already lost two infant sons, he left a six day old daughter to succeed to the Scottish throne. Her name would become well known to history, Mary Queen of Scots, but that is another story. James was buried beside his Summer Queen in Holyrood Abbey.

https://royalcentral.co.uk/features/history-blogs/the-tragic-tale-of-madeleine-of-valois-the-summer-queen-of-scots-146769/ |

|

|

|

Réponse |

Message 58 de 58 de ce thème |

|

Madeleine de France, Queen of Scotland, 1536

(Madeleine de France (1520-37) Queen of Scotland, 1536 )

|

https://www.meisterdrucke.us/fine-art-prints/Corneille-de-Lyon/80721/Madeleine-de-France,-Queen-of-Scotland,-1536.html

SCOTTISH RITE BLOG

The House of the Temple: A History

The House of the Temple is a Masonic temple in Washington, D.C. that serves as the headquarters of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, Southern Jurisdiction.

“The Temple should be built right, so that it could, and would be pointed to, by our brethren here and elsewhere, as the pride of the Mother Council of the Rite and all Scottish Rite Masons in the world. We are building a Temple, a permanent home, in the Great Capital of the Greatest nation of the Earth. I would prefer to be criticized for building a Temple, considered by some, too fine and costly, rather than for a cheap or mediocre building, surrounded as it will be, by the beautiful structures of our Capital. Better not build at all, than only half way build, while we are engaged in the laudable enterprise. (1911 Transactions, p. 125). — Grand Commander James D. Richardson (1911)

From the Masonic Temple in Detroit to Freemasons Hall in Copenhagen, Masonic structures around the world proudly represent our ancient fraternity. For over a century, the House of the Temple in Washington, D.C. has been one of the most awe-inspiring monuments to Freemasonry in the United States. Today, this majestic building serves as the headquarters of the Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction. It also houses an extensive library and archives responsible for preserving records that are valuable pieces of Scottish Rite history.

The Scottish Rite of Freemasonry's House of the Temple in Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C. The Scottish Rite of Freemasonry's House of the Temple in Dupont Circle, Washington, D.C.

Breaking Ground

In October 1909, the Supreme Council of the Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction passed a resolution to enlarge or extend the existing House of the Temple in Washington, D.C., or to erect a new one. With a grand vision for the Scottish Rite headquarters, Grand Commander James D. Richardson sought to erect a magnificent new building that would inspire Scottish Rite Freemasons everywhere.

The search for designs began immediately and the winning submission was awarded to American architect John Russell Pope. Pope’s firm is now famous for designing several prominent public buildings in Washington, D.C., including the National Archives and Records Administration building, the Jefferson Memorial, and the West Building of the National Gallery of Art. At the time, however, Pope was an ambitious young architect attempting to make a name for himself. Pope's design for the new Temple was based on one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World: The Tomb of Mausolus at Halicarnassus, Turkey.

The House of the Temple during construction. The House of the Temple during construction.

On April 16, 1910, the Scottish Rite officially hired Pope to make "the new Temple as magnificent as art and money can make it." The groundbreaking for the new House of the Temple was scheduled to occur in the following spring on May 31, 1911 (the 110th anniversary of the Supreme Council’s founding). The ceremony for laying the cornerstone was held later that year on October 18th and used the same Bible, candlesticks, trowel, and gavel used by Freemason and President George Washington when he laid the cornerstone of the U.S. Capitol in 1793.

There is little debate that Pope successfully achieved the Grand Commander’s vison of building a spectacular Masonic temple. Sadly, Grand Commander Richardson passed away on July 24, 1914, before he could see the new House of the Temple completed. Construction on the building finished over a year after his death, in October 1915. Richardson’s successor, Grand Commander, George F. Moore, led the dedication ceremony opening the Supreme Council’s new headquarters.

A Structure of Great Renown

When visiting the House of the Temple, it is easy to be overwhelmed by the beauty of such an artistic and architectural accomplishment. Pope’s peers seemed to agree; in January 1916, the London Architectural Review wrote "this monumental composition may surely be said to have reached the high-water mark of achievement in that newer interpretation of the Classic style with which modern American architecture is closely identified."

Indeed, it was years before praise for the structure simmered down. In 1917, the design received the gold medal from the Architectural League of New York. During the 1920s, the House of the Temple was ranked as one of the three best public buildings in the United States.

Art historian Royal Cortissoz wrote of the building in The Architecture of John Russell Pope, Vol. 2: "I cannot write temperately of the Temple of the Scottish Rite in Washington. I never see it without an uplifting of the heart; it is so vitalized an expression of imaginative power."

Architectural Significance

The House of the Temple is an essential part of Masonic history and not only because it houses one of the two governing bodies of Scottish Rite Freemasonry in the United States. Despite not being a Mason himself, John Russell Pope incorporated Masonic signs, symbols, and ideals into the building’s design, ensuring it would stand as a genuine monument to Scottish Rite Freemasons.

The House of the Temple’s interior granite stairs. The House of the Temple’s interior granite stairs.

Inside the building, the granite stairs rising from the building’s main entrance are arranged in groups of three, five, seven, and nine, reflecting the sacred numbers of Pythagoras. Additionally, two sphinxes – Wisdom and Power – sit on either side of the main entrance. On the way up to the Temple Room, two black Egyptian marble statues are inscribed with hieroglyphics that precede the name of a god or a sacred place flank the ceremonial staircase.

The House of the Temple’s interior windows. The House of the Temple’s interior windows.

Inside the Temple room are large windows representing a Freemason’s progressive search for more light. In the center of these windows sits the double-headed eagle, the symbol of the Scottish Rite. Outside, there are 33 columns lining the Temple's facades, each standing 33 feet tall to the Scottish Rite’s famous 33rd degree.

Additionally, the remains of former Sovereign Grand Commander Albert Pike were moved from Oak Hill Cemetery in Georgetown to the House of the Temple in 1944. He is best known as the author of Morals and Dogma of the Ancient and Accepted Scottish Rite of Freemasonry, a book that describes in detail the 33 degrees of Scottish Rite Freemasonry, the stories and teachings associated with each rank, the rituals connected to each rank, and other lodge proceedings. Past Grand Commander John Henry Cowles was also entombed in the temple in 1952, after his 31-year reign as Grand Commander.

Library and Archives

Many of the Scottish Rite, Southern Jurisdiction’s earliest records were lost not long after it was founded through a combination of disasters. Albert Pike famously emphasized the importance of cataloguing and preserving Masonic artifacts and documents, instilling a tradition of archiving still practiced in the modern Scottish Rite.

The library within the House of the Temple. The library within the House of the Temple.

Today, the headquarters of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry for the Southern Jurisdiction, the House of the Temple includes office and functional spaces and archives, a library, and museum space. The library, which is the oldest library in Washington, D.C., is open to the public, as is the museum, which displays a variety of Masonic artifacts. It is also home to one of the largest collections of materials related to Scottish poet and Freemason Robert Burns.

The archives, which is broken into two areas, include some of the Scottish Rite's most precious books and artifacts, including original documents dealing with the fraternity’s founding, rituals, and current domestic and international affairs. The first storage area is the General Archives, which maintains the records of Active Members and Deputies, and is responsible for housing approximately two million items in archival cases and fireproof file drawers.

The other storage area is the Archives Vault, which preserves the most valuable manuscripts and books, including the Scottish Rite ritual collection, as well as those of foreign jurisdictions, and manuscript copies of books, both published and unpublished. The items in the archives are part of a valuable, delicate collection of records, with some dating back to the 1800s. Because of their condition and, in certain cases, confidential nature, visitors are not eligible to view them. Specific requests for archival information from legitimate Masonic and historic scholars and researchers are managed on an individual basis.

The House of the Temple was one of the first buildings in the city to earn an individual listing in the D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites. As part of the 16th Street Historic District, the Temple was listed in the D.C. Inventory of Historic Sites on November 8, 1964, and in the National Register of Historic Places on August 25, 1978.

In the most recent edition of the “Guide to the Architecture of Washington DC,” the description, in part, reads, "an awe-inspiring temple in the midst of a quiet enclave." Most recently, in his book, “John Russell Pope: Architect of Empire”, Steven Bedford calls it "one of America's greatest architectural achievements."

Since it first opened in 1915, the House of the Temple has been open to the public for guided tours. Visitors interested in experiencing this monument to Masonic history and American architecture can receive a free, guided tour during weekdays. You can learn more about visiting The House of the Temple here: Planning Your Visit.

https://scottishritenmj.org/blog/house-of-temple-history

|

|

|

Premier Premier

Précédent

44 a 58 de 58

Suivant Précédent

44 a 58 de 58

Suivant

Dernier

Dernier

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Tous droits réservés | |

|

|

Madeleine of Valois

Madeleine of Valois