Jerusalem

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre in the Old City of Jerusalem covers what Christians believe is the site of the most important event in human history: The place where Jesus Christ rose from the dead.

But the pilgrim who looks for the hill of Calvary and a tomb cut out of rock in a garden nearby will be disappointed.

• At first sight, the church may bring on a sense of anticlimax. Looking across a hemmed-in square, there is the shabby façade of a dun-coloured, Romanesque basilica with grey domes and a cut-off belfry.

• Inside, there is a bewildering conglomeration of 30-plus chapels and worship spaces. These are encrusted with the devotional ornamentation of several Christian rites.

This sprawling Church of the Holy Sepulchre displays a mish-mash of architectural styles. It bears the scars of fires and earthquakes, deliberate destruction and reconstruction down the centuries. It is often gloomy and usually thronging with noisy visitors.

Yet it remains a living place of worship. Its ancient stones are steeped in prayer, hymns and liturgies. It bustles daily with fervent rounds of incensing and processions.

This is the pre-eminent shrine for Christians, who consider it the holiest place on earth. And it attracts pilgrims by the thousand, all drawn to pay homage to their Saviour, Jesus Christ.

Church replaced pagan temple

Early Christians venerated the site. Then the emperor Hadrian covered it with a pagan temple.

Only in AD 326 was the first church begun by the emperor Constantine I. He tore down the pagan temple and had Christ’s tomb cut away from the original hillside. His mother, St Helena, found the cross of Christ in a cistern not far from the hill of Calvary.

Constantine’s church was burned by Persians in 614, restored, destroyed by Muslims in 1009 and partially rebuilt. Crusaders completed the reconstruction in 1149. The result is essentially the church that stands today.

Making sense of the church

Of all the Christian holy places, the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is probably the most difficult for pilgrims to come to terms with.

To help make sense of it, this article deals with the church’s major elements and its authenticity. A further article, Church of the Holy Sepulchre chapels, deals with its other devotional areas.

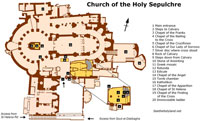

1. The main access to the church, on its south side, is from the Souk el-Dabbagha, a street of shops selling religious souvenirs. Visitors enter the left-hand doorway (the right one was blocked up by Muslim conquerors in the 12th century).

2. Instead of following tourists into the often-gloomy interior, immediately turn hard right and ascend a steep and curving flight of stairs. You are now ascending the “hill” of Calvary (from the Latin) or Golgotha (from the Aramaic), both words meaning “place of the skull”. The stairs open on to a floor that is level with the top of the rocky outcrop on which Christ was crucified. It is about 4.5 metres above the ground floor.

3. Immediately on the right is a window looking into a small worship space called the Chapel of the Franks. Here the Tenth Station of the Cross (Jesus is stripped of his garments) is located.

On the floor of Calvary are two chapels side by side, Greek Orthodox on the left, Catholic on the right. They illustrate the vast differences in liturgical decoration between Eastern and Western churches.

4. The Catholic Chapel of the Nailing to the Cross is the site of the Eleventh Station of the Cross (Jesus is nailed to the cross). On its ceiling is a 12th-century medallion of the Ascension of Jesus — the only surviving Crusader mosaic in the building.

5. The much more ornate Greek Chapel of the Crucifixion is the Twelfth Station (Jesus dies on the cross). Standing here, it is easy to understand a little girl’s remark, quoted by the novelist Evelyn Waugh in 1951: “I never knew Our Lord was crucified indoors.”

6. Between the two chapels, a Catholic altar of Our Lady of Sorrows commemorates the Thirteenth Station (Jesus is taken down from the cross).

7. A silver disc beneath the Greek altar marks the place where it is believed the cross stood. The limestone rock of Calvary may be touched through a round hole in the disc. On the right, under glass, can be seen a fissure in the rock. Some believe this was caused by the earthquake at the time Christ died. Others suggest that the rock of Calvary was left standing by quarrymen because it was cracked.

8. Another flight of steep stairs at the left rear of the Greek chapel leads back to the ground floor.

9. To the left is the Stone of Anointing, a slab of reddish stone flanked by candlesticks and overhung by a row of eight lamps. Kneeling pilgrims kiss it with great reverence, although this is not the stone on which Christ’s body was anointed. This devotion is recorded only since the 12th century. The present stone dates from 1810.

10. On the wall behind the stone is a Greek mosaic depicting (from right to left) Christ being taken down from the cross, his body being prepared for burial, and his body being taken to the tomb.

11. Continuing away from Calvary, the Rotunda of the church opens up on the right, surrounded by massive pillars and surmounted by a huge dome. Its outer walls date back to the emperor Constantine’s original basilica built in the 4th century. The dome is decorated with a starburst of tongues of light, with 12 rays representing the apostles.

12. In the centre is a stone edicule (“little house”), its entrance flanked by rows of huge candles. This is the Tomb of Christ, the Fourteenth Station of the Cross. This stone monument, held together by a steel frame, encloses the tomb (sepulchre) where it is believed Jesus Christ lay buried for three days — and where he rose from the dead. A high-tech photogrammetric survey late in the 20th century showed that the present edicule contains the remains of three previous structures, each encasing the previous one, like a set of Russian dolls.

13. At busy times, Greek Orthodox priests control admission. Inside there are two chambers. In the outer one, known as the Chapel of the Angel, stands a pedestal containing what is believed to be a piece of the rolling stone used to close the tomb.

14. A very low doorway leads to the tomb chamber, lined with marble and hung with holy pictures. On the right, a marble slab covers the rock bench on which the body of Jesus lay. It is this slab which is venerated by pilgrims, who customarily place religious objects and souvenirs on it.

The slab was deliberately split by order of the Franciscan custos (guardian) of the Holy Land in 1555, lest Ottoman Turks should steal such a fine piece of marble.

Three denominations share ownership

Ownership of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre is shared between the Greek Orthodox, Catholics (known in the Holy Land as Latins) and Armenian Orthodox.

Katholikon (or Greek choir), the central worship space in Church of the Holy Sepulchre (Seetheholyland.net)

The Greeks (who call the basilica the Anastasis, or Church of the Resurrection) own its central worship space, known as the Katholikon or Greek choir. The Armenians own the underground Chapel of St Helena which they have renamed in honour of St Gregory the Illuminator.

The Catholics own the Franciscan Chapel of the Apparition (which commemorates the tradition that the risen Christ first appeared to his Mother) and the deep underground Chapel of the Finding of the Cross.

Three minor Orthodox communities, Coptic, Syriac and Ethiopian, have rights to use certain areas. The Ethiopian monks live in a kind of African village on the roof, called Deir es-Sultan.

The rights of possession and use are spelt out by a decree, called the Status Quo, originally imposed by the Ottoman Turks in 1757. It even gives two Muslim families the sole right to hold the key and open and close the church — a tradition that dates back much further, to 1246.

Ladder symbolises Status Quo

Each religious community guards its rights jealously. The often-uneasy relationship laid down by the Status Quo is typified by a wooden ladder resting on a cornice above the main entrance and leaning against a window ledge.

The ladder has been there so long that nobody knows how it got there. Various suggestions have been offered: It was left behind by a careless mason or window-cleaner; it had been used to supply food to Armenian monks locked in the church by the Turks; it had served to let the Armenians use the cornice as a balcony to get fresh air and sunshine rather than leave the church and pay an Ottoman tax to re-enter it.

The ladder appears in an engraving of the church dated 1728, and it was mentioned in the 1757 edict by Sultan Abdul Hamid I that became the basis for the Status Quo.

It would be too much to expect that the ladder seen today has resisted the elements since early in the 18th century. In fact the original has been replaced at least once.

In 1997 the ladder suddenly disappeared for some weeks, after a Protestant prankster hid it behind an altar. When it was discovered and returned, a steel grate was installed over the lower parts of both windows above the entrance. And in 2009 the ladder mysteriously appeared against the left window for a day.

The ladder, window and cornice are all in the possession of the Armenian Orthodox. And because the ladder was on the cornice when the Status Quo began in 1757, it must remain there.