|

|

“Banking secrecy has its roots in Calvinism”

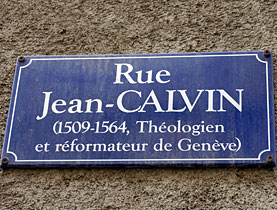

Calvin's influence spread well beyond Geneva RDB Calvin's influence spread well beyond Geneva RDB

Today's Switzerland - and its cherished bank secrecy - still reflect the influence of church reformer Jean Calvin, an economic think tank director tells swissinfo.

This content was published onApril 26, 2009 - 10:21

6 minutes

Xavier Comtesse, who heads the western Swiss branch of Avenir Suisse, says Calvin stood for morality in the granting of credit, but also for protection of the personal sphere.

This year marks the 500th birthday of the religious reformer whose ideas shaped the Protestant Church. In his honour Protestant denominations have designated 2009 Calvin Year.

Calvin, who spent much of his time working in Geneva, not only influenced democracy in Switzerland but modern-day thinking on both moral and financial matters, Comtesse believes.

swissinfo: What is the basis of Calvin’s Protestantism?

Xavier Comtesse: It is based on the Bible written in the language of the people, on the separation of church and state, and on the understanding that the grassroots faithful – who fund the community – choose their own priests.

This Calvinist form of institutional organisation has also over time had an influence on non-religious areas of the Swiss mentality. All state institutions remain separate from religious ones, and bottom up participation in political decisions continues from communal to national level.

Both lead to an emancipation of the people, an ’empowerment’, as we say today.

swissinfo: What would Switzerland look like today without Calvin?

X.C.: I don’t think we’d have direct democracy without this popular emancipation that was spurred on by Calvin. We would probably be a republic [with an elected president], like our neighbours. Of course when talking about German-speaking Switzerland we should mention [Zurich reformer Huldrych] Zwingli just as much as Calvin.

This communication from community organisations up to the highest state level is typical for us Swiss.

swissinfo: To what extent was Geneva more significant than Zurich?

X.C.: In those days French-speaking Switzerland did not exist. Geneva was the place to be – across the whole country. Basel was worth considering, but Zurich wasn’t. Neither was Bern nor Lausanne.

That is also why Calvin is rated so much more important internationally than Zwingli. Even in the post-Napoleonic period Zurich was smaller than Geneva both in the number of inhabitants and economically.

swissinfo: How did Calvin stamp the mark of the Reformation and the image of Switzerland on the world?

X.C.: I know most about his influence on the United States. There Calvinism is very pronounced with around 15 million Calvinists – called Presbyterians in Anglo-Saxon countries.

There are also communities in Scotland and South Korea. Worldwide there are said to be around 50 million Presbyterians. But there are very few of them in Switzerland.

swissinfo: What was Calvin’s influence on the economy and banking?

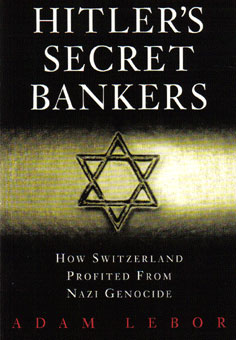

X.C.: As a reaction to the papal selling of indulgences as a mean of raising money for Rome, Calvin was one of the first church leaders to permit the granting of loans with interest – albeit tied to high moral standards.

That forged a link with the present: extortionate interest didn’t come into question, therefore the loans had to be cheap. As in religion and politics, the thinking behind this banking was to protect the citizen through high moral standards.

Also considered worth protecting by Protestantism was the personal sphere. Add this to being able to bank and you get banking secrecy.

swissinfo: Historically banking secrecy was meant to protect citizens from state interference.

X.C.: Exactly. And that’s why there are many misunderstandings concerning the term. The description ‘banking secrecy’ is actually incorrect – ‘protection of the private sphere by the bank’ would be more appropriate.

Such legal protection is not unique to Switzerland. In France for example a wife has no right to any information about her husband’s bank account – French legal law considers that his private sphere.

We Swiss simply go one step further. We protect against any state despotism. This way of thinking has historical roots in Protestantism, which in Calvin’s time sought to protect the people against the despotism of the powerful Catholic Church.

swissinfo: What remains from these Calvinist ethics today – bearing in mind the drama playing out in the world of banking and finance?

X.C.: At the moment we’re in a moral crisis. As a result we’ll soon have to grapple more with social responsibility.

That will be a form of secular Calvinism with new, still moral, but no longer religious characteristics. Regarding quality for example – new ISO standards in the area of quality attempt to rectify deficits in the area of responsibility.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is based in Geneva – like many other international institutions. This is also part of Calvin’s legacy.

Another ‘Geneva’ institution is the World Wide Web – invented at Cern. This also works ‘Calvinistically’ insofar as it enables direct access to information to the population, or rather the user.

Until now, powerful intermediaries were needed for this access. The internet has reformed access to the markets – similar to Calvin’s reformation of direct access to God.

swissinfo-interview: Alexander Künzle

|

|

|

|

|

Was Steve Jobs actually Satoshi Nakamoto the creator of Bitcoin? ????

Satoshi Nakamoto is the anonymous creator of the revolutionary system known as $Bitcoin (BTC.CC.CC)$. It provided a trustless, decentralized way to transact value across the internet, eliminating the need for an intermediary. Through this innovation, Satoshi Nakamoto paved the way for countless future blockchain applications.

Third-Party arts, logos and marks are registered trademarks of their respective owners.

The real identity of Satoshi Nakamoto has never been revealed and the likelihood of Steve Jobs, Founder of $Apple (AAPL.US)$, being Satoshi Nakamoto rest in the speculation that his death properly aligned with the disappearance of Satoshi Nakamoto on the internet. In truth, the identity of the creator remains unknown, so it is simply a theory that Steve Jobs was the person behind it all.

Third-Party arts, logos and marks are registered trademarks of their respective owners.

Many experts believe Satoshi Nakamoto was a group of individuals given the complexity of the code and the fact that the code was written over the course of several years — starting in 2007. The network was launched in 2009 and the white paper found on MacOS, "Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System", was first published in 2008 to describe the fundamentals of the system:

Third-Party arts, logos and marks are registered trademarks of their respective owners.

The true developer of Bitcoin has never been officially revealed leaving HIS -or- HER identity to great speculation.

https://www.moomoo.com/community/feed/110163576946693

|

|

|

|

|

Bitcoin Lecture at CERN, December 2 and 3

wo-parts lecture on Introduction to Cryptography and the Bitcoin Protocol will be given at CERN, in Geneva (Switzerland), on December 2 (Part 1) and December 3 (Part 2), from 11am to noon on both days. CERN, one of the most prestigious research laboratories in the world, is also the birthplace of the World Wide Web and the modern Internet, which gives this event a special symbolic significance.

The lectures are part of the CERN Academic Training Lectures program, open to all members of CERN personnel (in particular staff members and fellows, associates, students, users, project associates and apprentices) free of charge. The lectures are not officially open to the public, but many people in Geneva have friends or acquaintances at CERN, so getting an invitation to enter the CERN campus shouldn’t be too much of a problem for those who really want to attend the lectures.

Introduction to Cryptography and the Bitcoin Protocol

Cryptography is a key element of many Internet protocols – used for ensuring privacy, integrity, and security. Topics to be covered will include symmetric encryption, asymmetric encryption (public/private keys), digital signing and cryptographic hashing. These topics will serve as background information for the lecture on an Introduction to Bitcoin. The Bitcoin protocol not only supports an electronic currency, but also has the possibility for being (mis)used in other ways. Topics will include the basic operation of how Bitcoin operates including motivations and also such things as block chaining, bitcoin mining, and how financial transactions operate. A knowledge of the topics covered in the Basic Cryptography lecture will be assumed.

The lecturer is Bob Cowles, a Cyber Security Expert at BrightLite Information Security. Cowles was Chief Information Security Officer at SLAC, another prestigious research laboratory, for fifteen years until 2012.

What do you think of this high-profile Bitcoin event at the birthplace of the Web? Comment below!

Images from CERN and Wikimedia Commons.

https://www.ccn.com/bitcoin-lecture-cern-december-2-3/

|

|

|

|

|

Aunque Ginebra se menciona en escritos de Julio César en latín como Genava (Génava), durante la Guerra de las Galias, el nombre en sí mismo es de origen céltico. Este también ha sido transformado por otras culturas. Por ejemplo, Ginebra es llamada Geneva en inglés y arpitano. |

|

|

|

|

Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( EYEN-styne;[5] German: [ˈalbɛɐt ˈʔaɪnʃtaɪn] ⓘ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist who is widely held as one of the most influential scientists. Best known for developing the theory of relativity, Einstein also made important contributions to quantum mechanics.[1][6] His mass–energy equivalence formula E = mc2, which arises from special relativity, has been called "the world's most famous equation".[7] He received the 1921 Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services to theoretical physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect",[8] a pivotal step in the development of quantum theory.

Born in the German Empire, Einstein moved to Switzerland in 1895, forsaking his German citizenship (as a subject of the Kingdom of Württemberg)[note 1] the following year. In 1897, at the age of seventeen, he enrolled in the mathematics and physics teaching diploma program at the Swiss federal polytechnic school in Zürich, graduating in 1900. In 1901, he acquired Swiss citizenship, which he kept for the rest of his life. In 1903, he secured a permanent position at the Swiss Patent Office in Bern. In 1905, he submitted a successful PhD dissertation to the University of Zurich. In 1914, he moved to Berlin in order to join the Prussian Academy of Sciences and the Humboldt University of Berlin. In 1917, he became director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Physics; he also became a German citizen again, this time as a subject of the Kingdom of Prussia.[note 1] In 1933, while Einstein was visiting the United States, Adolf Hitler came to power in Germany. Horrified by the Nazi war of extermination against his fellow Jews,[9] Einstein decided to remain in the US, and was granted American citizenship in 1940.[10] On the eve of World War II, he endorsed a letter to President Franklin D. Roosevelt alerting him to the potential German nuclear weapons program and recommended that the US begin similar research. Einstein supported the Allies but generally viewed the idea of nuclear weapons with great dismay.[11]

Einstein's work is also known for its influence on the philosophy of science.[12][13] In 1905, he published four groundbreaking papers, sometimes described as his annus mirabilis (miracle year). These papers outlined a theory of the photoelectric effect, explained Brownian motion, introduced his special theory of relativity—a theory which addressed the inability of classical mechanics to account satisfactorily for the behavior of the electromagnetic field—and demonstrated that if the special theory is correct, mass and energy are equivalent to each other. In 1915, he proposed a general theory of relativity that extended his system of mechanics to incorporate gravitation. A cosmological paper that he published the following year laid out the implications of general relativity for the modeling of the structure and evolution of the universe as a whole.[15][16]

In the middle part of his career, Einstein made important contributions to statistical mechanics and quantum theory. Especially notable was his work on the quantum physics of radiation, in which light consists of particles, subsequently called photons. With the Indian physicist Satyendra Nath Bose, he laid the groundwork for Bose-Einstein statistics. For much of the last phase of his academic life, Einstein worked on two endeavors that proved ultimately unsuccessful. First, he advocated against quantum theory's introduction of fundamental randomness into science's picture of the world, objecting that "God does not play dice".[17] Second, he attempted to devise a unified field theory by generalizing his geometric theory of gravitation to include electromagnetism too. As a result, he became increasingly isolated from the mainstream modern physics. His intellectual achievements and originality made Einstein broadly synonymous with genius.[18] In 1999, he was named Time's Person of the Century.[19] In a 1999 poll of 130 leading physicists worldwide by the British journal Physics World, Einstein was ranked the greatest physicist of all time.[20]

Life and career

Childhood, youth and education

Einstein in 1882, age 3

Albert Einstein was born in Ulm,[21] in the Kingdom of Württemberg in the German Empire, on 14 March 1879.[22][23] His parents, secular Ashkenazi Jews, were Hermann Einstein, a salesman and engineer, and Pauline Koch. In 1880, the family moved to Munich's borough of Ludwigsvorstadt-Isarvorstadt, where Einstein's father and his uncle Jakob founded Elektrotechnische Fabrik J. Einstein & Cie, a company that manufactured electrical equipment based on direct current.[21] He often related a formative event from his youth, when he was sick in bed and his father brought him a compass. This sparked his lifelong fascination with electromagnetism. He realized that "Something deeply hidden had to be behind things."[24]

Albert attended St. Peter‘s Catholic elementary school in Munich from the age of five. When he was eight, he was transferred to the Luitpold Gymnasium, where he received advanced primary and then secondary school education.

|

|

|

|

|

Bern Museums: Einstein’s House

By Emma Marshall

There are several Bern museums that you can visit in the Swiss capital.

However, if you’re in this lovely city, a World Heritage Site, and the place where Albert Einstein developed his theory of relativity, you really must put a visit to the house where he lived on your sightseeing list.

Read on for more information on visiting this Bern museum and for my thoughts on what I learnt here.

This post contains affiliate links

Bern Museums: where is the Einstein house?

The Albert Einstein house is situated in Bern old town, a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It’s on Kramgasse (specifically No.49). This is the main street that runs the length of the old town and which means “Grocer’s Alley”. It’s a lovely medieval street and you’re bound to visit it on a trip to Bern.

Kramgasse street There are long covered alleyways here, with small boutique shops under the arches. There’s also a smattering of cosy cafes and bars in basements, which would be perfect in the cold winter months.

The street is also is interspersed with a number of ornate, colourful, and quite unique fountains. At one end, you can also find the 13th century clock tower (Zytlogge). This is beautiful and lovely when lit up at night.

Bern clock tower in the old town  The Bern clock tower at night This is another must-see sight in Bern. So much so that you can book tours to learn more about the clock and to go inside. Click here to learn more.

You can also book walking tours of the old town: click here.

Bern Museums: why visit the Einstein House?

Einstein is not the only famous or noteworthy person connected to this Swiss canton. Others include the Nobel Prize winner, Emil Kocher, and the Bond actress Ursula Andress.

However, he is the one that the city – understandably – is most proud of.

This is because it was in Bern that he first sowed the seeds for his famed work on the General Theory of Relativity. He himself said: “Those were good times, the years in Bern”, of his seven years in the Swiss capital.

So when deciding which Bern museum to visit, you really should include one about Einstein.

You can actually learn about Einstein’s time in the Swiss capital in two Bern museums. Aswell as Einstein’s house, there is the Bern Historical Museum.

According to the website, this has “some 550 original objects and replicas, 70 films and numerous animations outline the biography of the genius and his ground-breaking discoveries”.

Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here As we had limited time in the capital, we chose to focus on Einstein’s house and the museum that is housed there. However, if I returned, I would definitely visit the Bern Historical Museum as well.

Bern Museums: The Einstein house

Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)The Einstein House is the flat that Einstein occupied from 1903 to 1905 with his wife, Mileva Maric. Mileva was herself a promising physicist from Serbia.

The house is very small, so this is a Bern museum that can get easily crowded. I’d therefore recommend visiting early to ensure you get in.

The museum has a large selection of exhibits and photographs from the couple’s life together. On the first floor, these are displayed around the flat as it presumably was laid out at the time.

Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)A small table is in the middle of the room where the family would have eaten. Chairs are where they would have relaxed, and there is a writing bureau, and cabinet housing a tea service and coffee pots.

All are overlooked by fascinating old photos of the family that hang on the walls and that depict different chapters of their life.

Upstairs, there is an informative short film. This draws on archive footage, that charts Einstein’s life from his early days through to later years. Make sure you watch this – it is essential viewing. It really brings alive the life of the man.

Bern Museums: What’s interesting about this particular museum?

Einstein’s work

The museum is interesting on several levels. Firstly, for what you learn about Einstein’s great work and the foundations for this.

His first job was with the Swiss Patent Office which he held down whilst simultaneously writing his scientific papers. These included the forerunner to his work on the Theory of Relativity and another which won him a Nobel Prize in 1921.

He then moved into academia at the University of Bern before moving to Zurich. There were other stints in Prague and Berlin, before his later life spent in the United States.

Einstein’s personal life

This Bern Museum is also interesting for the insight it gives you into the personal life of Einstein. I found this utterly engrossing.

We all grow up knowing that Einstein is significant for his scientific work and discoveries. What we know less about (or certainly I knew less about) are the life stories running alongside in the background.

Much of this revolves around Einstein’s personal relationships and the consequences of these. Some of these are very sad. For example, he had a child born out of wedlock and a second relationship while still married.

He married Mileva Malic in 1903, but had in fact had a daughter, Leiserl, with Mileva the previous year. Leiserl was born in Mileva’s home country of Serbia. She was left to grow up with her grandparents, presumably because she was illegitimate.

According to the museum exhibition, Einstein himself never met his daughter. Her sheer existence was kept secret during his lifetime. To this day what happened to Liserl is a mystery.

Mileva and Einstein went on to raise two sons, Hans Albert and Eduard. They remained married until 1919 when Einstein remarried – to his cousin, Elsa Lowenthal. It seems he had forged a relationship with her some time before his marriage to Mileva formally dissolved.

Einstein’s move to the USA

The museum also tells the story of Einstein’s move to the USA. This coincided with the rise of the Nazi party in Germany and the difficulties that this presented to him.

Most notably these included the impossibility of working there as a German Jew. Scores of Jewish academics were being forced out of work, Nazi book burnings were taking place, and Einstein was vocalising his views on the treatment of Jews within Germany.

He therefore took up a role at Princeton University in the USA, and it is there that he remained until his death in 1955.

Einstein’s wife

Although this Bern museum is only small, you can learn a great deal in a short time, some of it possibly unexpected. And whilst I went to learn more about Einstein, I came away with a long lasting impression of his wife.

I developed an equal admiration for his wife, partly because of all that she seemed to go through during her time with Einstein. This included a child that was given up, a broken marriage and the forfeiture of her own academic ambitions.

It also seems that Mileva may have been important not only for her support of Einstein’s ambitions, but more directly for her role in actually furthering these.

Some think that letters between the couple show her contribution. It is thought that she contributed in the early days to Einstein’s ground-breaking work and that her own expertise in physics is reflected in some of his work.

So, in addition to learning a lot about Einstein himself, I learnt a lot about the wife of one of the world’s greatest scientists. I came away with a real sense that the adage about there being a great woman behind every man was really true of Mileva.

Bern Museums: visiting the Einstein house

Opening times

You can visit the house between 1st February and 21st December. Exceptions include Easter, Pentecost and Switzerland’s National Day (1st August).

Opening times are 9am to 5pm. Entry costs CHF 6 for adults (reduced rates apply for students, pensioners and those between 8 and 15 years: CHF 4.50, 4.50 and 3, respectively).

Getting to Bern

Bern has an airport and you can catch flights here from various cities in Germany, as well as from London (City airport), Vienna and Palma.

However, it is smaller than both the Swiss airports in Geneva and Zurich that have more regular flights. Bern is just over an hour via train from Zurich airport and around two hours to Geneva airport. You might therefore find it more convenient to catch a flight to one of these airports.

You can also visit Bern from other Swiss cities. Lausanne and Lucerne are both around an hour away by train. Interlaken is around 45 mnutes and Nuechatel just under 50 minutes.

If public transport is not your thing, you can also book day trips to Bern. Click here for ideas.

Other Bern Museums to visit

Aside from the history museums, there are other Bern museums to visit.

These include a fine arts museum, a communications museum and a Swiss alpine museum – see http://www.museen-bern.ch/en/for further information.

If you enjoy short trips to Europe, you may also find some of my other posts of interest:

https://www.travelonatimebudget.co.uk/switzerland/bern-museums-einsteins-house/ |

|

|

|

|

Criptocomunismo o ¿la ideología bitcoin?

RESEÑA

Publicado en el año 2020, el filósofo francés Mark Alizart nos presenta un trabajo donde analiza el origen y desarrollo de la más famosa de las criptomonedas, el bitcoin, con el fin de explicar y justificar por qué en el software libre blockchain se encontraría la clave para cumplir el objetivo político de Marx: destruir el Estado y crear una sociedad comunista, pero fundada en la criptografía y no en la lucha de clases.

Mark Alizart es un filósofo francés contemporáneo que desde hace aproximadamente una década viene publicando obras en las que discute temáticas contemporáneas desde su particular óptica filosófica: entre sus trabajos destacados está Teología Pop (2015), donde afirma que la sociedad del entretenimiento, el ocio y el consumo debe su forma a la religión, y más específicamente a la ética protestante que Max Weber y su interpretación del capitalismo; en Golpe de estado climático (2020) denuncia la voluntad política de que el clima esté en crisis debido a que vivimos en un golpe “carbofascista” contra la humanidad y la única salida es pensar las condiciones de una revolución en favor de un verdadero “ecosocialismo”. Finalmente llegamos a su último trabajo que vamos a analizar en este artículo Criptocomunismo, un libro donde abundan las tesis, afirmaciones y criticas al marxismo de toda forma y color (sin mucho fundamento) pensando en la tecnología blockchain como herramienta emancipadora y salvadora de la humanidad frente a las crisis económicas (pasadas y venideras).

Apropiación colectiva de los medios de producción monetaria

Corría el año 2008 cuando en los Estados Unidos de Norteamérica estalló la “burbuja inmobiliaria”, o la crisis más importante de la historia contemporánea del capitalismo; el gobierno norteamericano, para evitar la caída y posterior crack financiero de su país, decide socializar las pérdidas de la banca privada absorbiendo sus deudas con fondos públicos y generando una situación de crisis económica y social en la población trabajadora que se tradujo en la expropiación (lisa y llana) de ahorros particulares y viviendas hipotecadas.

El 1.° de noviembre del 2008 un usuario con el seudónimo de Satoshi Nakamoto subió a la red una publicación titulada: “Bitcoin: un sistema de efectivo electrónico de usuario a usuario”. En dicho texto se sientan las bases de los protocolos de programación que dan por resultado el modelo criptográfico que da nacimiento a la primera criptomoneda: el bitcoin. En respuesta al rescate financiero de la banca privada por parte de la Reserva Federal de los EE. UU., Satoshi propone la creación de una cyber-moneda que sirva de resguardo y protección de los ahorros particulares ante una nueva amenaza de rescate de los bancos privados por parte del gobierno federal usando fondos públicos.

Para Alizart, el “bitcoin fue concebido para proteger el ahorro privado, para salvarlo de la voracidad de los gobiernos, aún en el caso de que se tratara de participar en un esfuerzo colectivo, incluso sobre todo en el caso de que se tratara de ‘socializar’ las perdidas” [1].

Cripto la solución

Según Alizart, en el software libre bitcoin se encuentra la clave para destruir al Estado y lograr una representación individual lo más directa y menos mediada posible. Todo un programa político revolucionario en el código de un software: “Bitcoin es un algoritmo de fe. Al permitir librarse matemáticamente de los ‘terceros de confianza’, bitcoin es una máquina de producir fe y libertad” [2].

En ese sentido Alizart nos plantea que en la filosofía blockchain del bitcoin se encuentran elementos de corte político que permitirían lograr un nuevo tipo de organización social comunitaria nunca antes vista por la humanidad, “una nueva ley, una nueva Iglesia y un nuevo Estado”, pero no de cualquier tipo ni de cualquier forma: esta será una revolución histórica más austera que las “reformas de Lutero” y con una voluntad general más fuerte que la “república de Rousseau”.

Entonces llegamos así a la tesis principal del libro: “el régimen teológico-político que la Cripto finalmente establecerá no es el ‘criptoanarquismo’. Por el contrario, es un régimen conocido precisamente por hacer que las personas reconozcan que viven en comunidades y no como átomos separados” [3]; es a partir de este uso de las criptomonedas que nacerá el “Criptocomunismo”.

La batería de argumentos a favor del universo Cripto van desde la no existencia de mediadores, el refuerzo de los lazos comunitarios, la destrucción organizada del Estado, minando lo que Alizart identifica como el corazón del capitalismo en el monopolio de producir dinero fiduciario (se llama dinero fiduciario al que se basa en la fe o confianza de la comunidad, es decir, se respalda por una promesa de pago por parte del ente emisor). Alizart afirma (sin fundamentación histórica alguna) que la cripto-revolución socialista es posible y además pacífica, ya que a diferencia del modelo social marxista que exige cambios profundos y radicales, “el ambiente de la Cripto pretende ser pragmático. No cree más que en lo que funciona. Y pretende conducir una revolución pacífica, ya que solamente está hecha por ingenieros desprovistos de prejuicios filosóficos” [4].

Según Alizart, el bitcoin va a permitir todo un universo de reformas estructurales de tinte mesiánico y profético que van desde el debilitamiento progresivo del capitalismo internacional, que va a colapsar a partir del momento en que el bitcoin suplante al dólar como unidad de valor mundial [¡¿?!], hasta el fin de la guerras entre Estados, que será posible ya que no van a poder financiar sus conflictos bélicos debido a que al no tener el monopolio de la moneda no van a poder recaudar impuestos.

Qué es un blockchain y cómo funciona

Pero ¿qué es lo novedoso o vanguardista de todo este asunto de la criptografía y el blockchain? Para Mark Alizart la creación del software libre blockchain (cadena de bloques) representa un salto cualitativo, cuantitativo y evolutivo en la historia de la humanidad. Pero vamos por partes.

El blockchain o cadena de bloques es una teoría de encriptamiento que Satoshi Nakamoto subió a la red en el 2008, cuando se minó (programó) el primer bloque de bitcoins de la historia. Según Satoshi, el protocolo de programación del blockchain es la respuesta a una teoría de juegos llamada El problema de los generales Bizantinos en donde la solución que se busca encontrar es cómo manejar información de forma segura y descentralizada. La paradoja es la siguiente: el ejercito invasor amenazada la ciudad y el comandante defensor debe dar la orden de atacar, pero debe ser en simultáneo entre todos sus ejércitos, si no la defensa pierde efectividad. Hay varios generales apostados listos para atacar, pero sus ejércitos están en posiciones separadas e incomunicadas, el único nexo comunicador es el mensajero oficial que debe llevar la orden en forma y tiempo a cada general para que sepan a qué hora exacta atacar; y es aquí donde surgen los problemas: ¿cómo sabemos si llegó el mensaje? ¿Cómo sabemos si el mensaje fue capturado? Y ¿óomo sabemos que el mensaje no fue alterado por un general traidor? La solución que propone Satoshi a este dilema es el protocolo blockchain.

Podemos definir el blockchain como un protocolo de programación para compartir información en internet, un protocolo de interacciones virtuales descentralizadas que permite intercambio de información entre bloques de datos. O sea: es una sintaxis digital (como el “http://”), una forma de organizar la información que circula en la web.

El blockchain funcionaría como un tipo de libro contable online. La base de toda esta información no tiene un servidor central sino que es público. Los registros contables son distribuidos en miles de computadoras, llamadas nodos, conectadas a internet, que se actualizan con cada transacción. La cadena entera puede ser auditada por quien lo desee. Cada transacción es certificada mediante pruebas de trabajo y se encripta (no se pueden hackear), lo que significa que no se puede falsificar ni adulterar; la cadena se verifica constantemente en cada operación. Y funciona con un esquema de dos claves, una pública y una privada. La clave pública autoriza a recibir bitcoins, mientras que la privada autoriza a que uno mueva los propios. En definitiva, el uso de las claves autoriza que las transacciones queden registradas en la cadena de bloques, evidencia de que los bitcoins han pasado de mano y pertenecen a un determinado usuario.

Hablemos también con Satoshi

Como vimos, Alizar sostiene que el bitcoin es mucho más que una simple moneda, sino una manifestación social de valor, ya que según él los bitcoins son una relación social cuyo valor esta determinado por la energía/electricidad necesaria para crearlo: “Bitcoin es energía cautiva (la energía que se necesita para crackear el criptograma)” [5].

En ese sentido Alizart afirma que el bitcoin no puede caer en el fetichismo de las monedas debido a dos razones: la primera consiste en que su valor esta determinado por su costo energético, y por otro lado que no puede ser falsificado. Pero ¿cómo se estructura una cadena de bitcoins? Un bloque minado de toda una cadena, uno solo, contiene 50 bitcoins. Y de la misma manera en que 1 peso esta compuesto de 100 centavos, un bitcoin esta compuesto por 100 millones de satoshis –un satoshi es la unidad mínima de un bitcoin–. Y es acá donde está lo esencial del bitcoin, ya que cada satoshi es un hash o si se quiere: un código alfanumérico compuesto de 35 dígitos 1GZPvex89rBMtrvYfFiqWJBTp7WNU55Cs, y esto es lo infalsificable del criptograma del blockchain. El mismo Satoshi ilustra la cuestión de la siguiente manera:

La criptografía de clave pública depende del hecho de que es difícil factorizar números primos grandes. Todos saben eso. Si las transferencias de bitcoins se asignaron a una clave pública bien formada, y se requirió una firma de clave privada asociada para la futura transferencia, permitiría que las transferencias cifradas de bitcoins fueran completamente seguras.

Para validar una transacción, los nodos toman la clave pública de la firma y la usan para verificar la firma real. Si la firma es válida, habrá que ver luego los hashes de la clave pública para confirmar que coincide con la dirección de bitcoin asignada en la transacción. Actualmente el hash es de 35 caracteres de longitud, alfanumérico 26 (mayúscula) + 26 (minúscula) + 10 (números) = 62 posibles por carácter. Entonces tenemos 541,638,008,296,341,754,635,824,011,376,225,346,986,572,413,939,634,062,667,808,768 combinaciones posibles. Así que creo que no tenemos mucho trabajo por hacer en comparación con ir con fuerza bruta contra la clave privada/pública principal [6].

Cada hash es único e irrepetible dentro del universo Cripto, por lo tanto es ese el parámetro que sugiere Satoshi para determinar el valor de cada hash; no es el costo energético de su acuñación/programación/minado (contar hashes) lo que determina su valor (como sugiere Mark Alizart) sino su valor simbólico; para Satoshi Nakamoto, cada hash es una obra de arte criptográfica en sí misma, y por lo tanto su valor es socialmente determinable; no es inmune al fetiche tal como lo entiende Alizart, no son más que meras fichas intercambiables. El propio Satoshi lo definió así: “Los bitcoins no tienen dividendos o potenciales futuros dividendos, por lo que no son como una acción. Más como un coleccionable o producto” [7].

¿La tecnología logrará el comunismo?

Todas las tesis que plantea Alizart a lo largo del libro se fundamentan en dos críticas (muy superficialmente planteadas) a Marx y su visión económica, donde ataca la visión fetichista del dinero que tendría este, y un cruce mecánico y desprolijo entre el concepto de economía y termodinámica.

Según Alizart, “Marx pasó por alto el papel que juega el dinero en la economía porque pasó por alto el papel que juega la información en la termodinámica” [8]. Esta crítica de Alizart a Marx merece especial atención por dos razones: la primera es que solamente una persona que no leyó El capital (o lo miró muy superficialmente) puede sostener que Marx pasó por alto el papel que juega el dinero en la economía, ya que en todo caso Karl Marx mostró que el dinero es una relación social y no un signo, como sostenían exponentes de la economía política de su época o una “cadena de información”, como parece creer Alizart.

En segundo lugar estaría la cruza mecánica de los conceptos: economía y termodinámica. Alizart considera al bitcoin como algo más que una simple moneda digital de cambio. Él ve una “criptomoneda viviente” que como tal produce no solo un valor de uso sino también relaciones sociales y estructuras políticas nuevas. Algo similar a lo que fueron las primeras máquinas a vapor del siglo XIX, que no solamente daban ganancias increíbles (en comparación con el sistema agrícola-artesanal) sino que literalmente esas máquinas permitieron que surja una clase social nueva que posteriormente se organizó políticamente en un partido y tomó poder por medio de la revolución de 1789, dando nacimiento a una sociedad nueva. El estudio de las leyes de la termodinámica aparecen a la par de las revoluciones industriales del siglo XIX con la llegada de la máquina de vapor; el estudio de las máquinas térmicas fue fundamental para hacer más eficientes los procesos de producción lo que, desde el punto de vista capitalista, significaba una mayor eficiencia y una mayor ganancia. Para Alizart, el bitcoin es un nuevo tipo de máquina a vapor cuya producción se mide no solo por su valor de uso y su valor de cambio, sino además por el valor en sí de la información política y social que puede producir el blockchain. Resumidamente podemos decir: la criptomoneda no solo es una moneda, tampoco es solo una máquina, sino que es una “cripto-moneda viviente” que además funciona como “una máquina de producir fe y libertad”.

Te puede interesar: ¿Fin del trabajo o fetichismo de la robótica?

Alizart ve en el bitcoin un tecno-fenómeno inédito que por sí solo va a revolucionar el sistema productivo, pero en sus afirmaciones se refleja un optimismo técnico digno de los socialistas-utópicos del siglo XVIII como Saint-Simon. Y por otro lado una “tecno-ingenuidad” escandalosa, ya que sin sonrojarse Alizart afirma que la revolución bitcoin va a ser pacífica porque la impulsan “ingenieros desprovistos de prejuicios filosóficos”, cuando si hay una lección que nos dejó en claro el siglo XX y dos guerras mundiales es que la ciencia de ninguna forma es neutral y absolutamente toda técnica o máquina que fabrica el capitalismo destila ideología. El bitcoin no está exento a eso.

Sin ir muy lejos, el propio Satoshi Nakamoto (2010) expuso públicamente en la red sus intereses políticos y morales cuando se negó a permitir que WikiLeaks use bitcoin como forma de financiamiento, ya que los problemas legales de Julian Assange y su campaña contra los secretos diplomáticos burgueses e imperialistas de EE. UU. podían “destruir la pequeña comunidad beta que todavía está en su infancia” como es bitcoin [9].

Por último, una observación de tipo técnica política: como desarrollamos arriba, el plus sociopolítico del bitcoin Alizart lo ubica en el blockchain como algo en sí mismo (es el blockchain lo que hace posible el criptocomunismo). Pero ¿qué es concretamente un blockchain?: es una sintaxis digital que ordena la información en la web, por lo tanto podemos afirmar que no es un software ni un hardware; pero entonces, sin internet no podría existir el bitcoin, el blockchain y por elevación el criptocomunismo. En sus afirmaciones Alizart demuestra que termina siendo un fetichista del dinero y la información.

A modo de cierre

El manifiesto de Mark Alizart es un conjunto de tesis, afirmaciones y criticas tan abundantes como poco desarrolladas en profundidad; apunta sus armas de la crítica contra el marxismo y el comunismo, pero sus armas son de cotillón, ya que todas sus tesis son engendros conceptuales, violentamente unidos, que dan como resultado definiciones contradictorias que son más provocadoras que teóricamente útiles; lo podemos ver en conceptos como “comunismo de las cosas”, “criptomoneda viviente”, “ingenieros sin ideología”, “máquinas que producen fe y libertad”, “termodinámica de la economía”, etc., etc.

En ese sentido podemos definir al manifiesto de Alizart Criptocomunismo como un intento retórico de querer contrabandear el concepto de comunismo bajo la idea de que una moneda emitida de forma privada (sin control estatal) y con las cadenas de información como garantía (blockchain) bastaría para disolver las cadenas de producción del capital y planificar la economía. Alizart establece una relación mecánica y superficial entre la economía y la criptografía dejando en evidencia el extremo fetichismo de dinero o información que expresa acríticamente por el bitcoin.

Te puede interesar: El carácter bifacético del trabajo que produce mercancías

Podemos afirmar que su libro es el exponente de un intento de conciliar (sin anestesia ni fundamento) corrientes como el neorreformismo y el postcapitalismo bajo el eufemismo de criptocomunismo con la idea de que se puede “superar” el capitalismo tan solo con la apropiación de los medios de producción monetarios.

https://www.laizquierdadiario.com.ve/Criptocomunismo-o-la-ideologia-bitcoin |

|

|

|

|

CRIPTOCOMUNISMO – MARK ALIZART

Descargar libro (epub)

Por Mark Alizart

Las criptomonedas a menudo son consideradas “revolucionarias” y es posible que lo sean. Y no solamente en un sentido metafórico, sino también histórico, político e incluso filosófico.

De hecho, la promesa de Satoshi Nakamoto de que es posible comerciar sin la intermediación de banqueros parece que podría desencadenar una revolución en la economía de la misma manera que Martin Lutero comenzó su revolución en la Iglesia en 1517, al afirmar que los creyentes podían tener una relación directa con Dios sin sacerdotes como intermediarios, o como Oliver Cromwell, George Washington o Maximilien de Robespierre provocaron una revolución en el Estado en los tiempos modernos al declarar que la gente podía gobernarse a sí misma sin príncipes como intermediarios.

Obviamente, el White Paper que en el 2009 dio origen a Bitcoin, la criptomoneda más famosa, no nos dice cómo obtener la vida eterna. Tampoco los pequeños cálculos de un pequeño inversor preocupado por sus ahorros parecen tener mucho en común con la lucha por la libertad. Sin embargo, la revolución que encarna es real. La economía es un aspecto fundamental de nuestras sociedades. Incluso comparte rasgos con las esferas religiosas y políticas.

Si las hostias tienen forma de moneda es porque originalmente se fundían en los mismos moldes1. El primer “banco central” de la historia, el Bank of England, fue fundado por los Puritanos ingleses en 1694. A menudo se cree, desde Max Weber, que el capitalismo fue conducido a las fuentes bautismales por la “ética del trabajo” protestante, pero el aporte más notable de la Reforma a la economía, más bien, fue la ingeniería financiera moderna2. Al volver a poner a la fe (fide) y a la culpabilidad en el centro de la vida religiosa, el protestantismo permitió que socios que se tienen “confianza” (con-fide) puedan darse “crédito” entre sí (crede, “creer”, “tener la fide”) para sus deudas (tanto morales como financieras). Por cierto, fue un protestante, John Law, quien a comienzos del siglo XVIII introdujo en Francia el primer papel moneda3. Y es también el concepto protestante de fe, en el sentido que supone confiar, ceder y, por lo tanto, ser libre, el que permitió que las democracias liberales se construyeran y emanciparan de la monarquía.

De hecho, el invento de Satoshi, en la medida en que también trata con la confianza y la fe, es un digno heredero de la historia teológica y política de Occidente4. Incluso puede que represente su cumplimiento. Mientras que la Reforma y la Revolución se basaron en un concepto subjetivo de fe, Bitcoin es un algoritmo de fe. Al permitir liberarse matemáticamente de los “terceros de confianza”, Bitcoin es una máquina de producir fe y libertad5.

Dicho esto, muchas ideas equivocadas rodean a las revoluciones y lo que ellas implican, y los “fanáticos” de las criptomonedas –palabra que podemos usar puesto que de hecho es una nueva religión y un nuevo partido– podrían decepcionarse respecto de las suyas.

Si las revoluciones del pasado nos enseñan algo, es que no son un camino en una sola dirección hacia la emancipación, la libertad [freedom] o la liberación [liberty]. La Reforma no puso fin al tráfico de personas en la religión, aunque hirió gravemente a la Iglesia; las revoluciones inglesa, estadounidense y francesa tampoco pusieron fin al Estado como tal, aunque detuvieron a la monarquía. De la misma manera, es dudoso que Bitcoin simplemente signifique el fin de los bancos centrales, del sistema financiero mundial y del Estado policial, solo para dar a luz a un mundo nuevo y valiente de individuos empoderados liberados de pagar impuestos y obedecer la ley, como lo expresaron muchos profetas libertarios, bitcoiners de alt-right y criptoculturistas.

Ciertamente, hubo campesinos que durante la Edad Media se reunieron en torno a los gurús de la Reforma como Thomas Müntzer, quienes dedujeron de las tesis de Lutero que ahora era posible vivir libres de toda autoridad moral y clerical. También hubo enragésrevolucionarios que creían que su libertad recién obtenida les daba el derecho de cortar tantas cabezas como quisieran, especialmente aquellas más altas que las suyas. Eventualmente, sin embargo, todos descubrirían más temprano que tarde que estaban equivocados sobre el significado más profundo de la Reforma y la Revolución. El protestantismo iba a introducir aún más rigor en la religión que el catolicismo, hasta el punto de que los protestantes terminarían siendo conocidos como “puritanos”. Se abolieron los sacerdotes, se destruyeron las catedrales, los altares, el incienso y el latín de la iglesia, solo para ser reemplazados por una práctica religiosa que, al eliminar todos los signos visibles, solo se hizo más ascética, y tuvo que ser observada en todo momento y en todos los aspectos de la vida secular. Del mismo modo, la democracia demostraría ser aún más compleja y enrevesada que el antiguo régimen. Los príncipes fueron abolidos solo para ver la burocracia desenfrenada, con enjambres de funcionarios y libros de leyes más gruesos que el diccionario y la guia telefónica combinados.

Ahora se podría argumentar que el regreso de la Iglesia y del Estado, después de la Reforma y las Revoluciones liberales que intentaron destruirlos, significa que fracasaron en lo que se suponía que debían hacer. La verdad es que este retorno fue una herramienta, no un error. Lutero no quería derrocar la ley de Dios, quería cumplirla. Rousseau no quería que la ley de la Naturaleza reemplazara la ley de los hombres, quería asegurarse de que se observara la ley de los hombres. De hecho, ambos habían entendido que la libertad era, paradójicamente, la mejor manera de hacer cumplir la ley de Dios y el gobierno de los hombres porque, en última instancia, la libertad no consiste en ser libre de toda ley, sino en imponerse libremente leyes a uno mismo, como la palabra “autonomía” lo dice claramente: una “ley” (nomos) impuesta sobre “uno mismo” (auto).

Lo mismo puede decirse sobre el proyecto de Satoshi. Quiere restaurar la confianza, no destruirla. Quiere restaurar las instituciones en las que podemos creer, no quemarlas. Y de una manera muy convincente, lo hace de la misma manera que la Reforma y las Revoluciones, al reemplazar las viejas instituciones por otras nuevas, que solo son más robustas porque son instituciones elegidas e impuestas libremente sobre nosotros. Bitcoin nos libera al encadenarnos, como la bien llamada blockchain lo establece claramente. La Cripto nos libera uniéndonos unos a otros. Es una institución de libertad, no la libertad de todas las instituciones.

Por lo tanto, no hay duda de que las criptomonedas traerán consigo un nuevo viento de cambio, extendiendo la libertad en todo el mundo, pero no de la forma en que los niñitos del Tea Party lo han soñado. Lo hará sometiendo nuestras vidas a una nueva ley, una nueva Iglesia y un nuevo Estado, aún más austeros que los de la Reforma de Lutero, más rigurosos que los de la República de Rousseau. Y esta es la razón por la cual este ensayo afirma que el régimen teológico-político que la Cripto finalmente establecerá no es el “criptoanarquismo”. Por el contrario, es un régimen conocido precisamente por hacer que las personas reconozcan que viven en comunidades y no como átomos separados, y por querer que compartan lo que tienen en común, en lugar de separarlo para su propio beneficio; un régimen que también se consideró revolucionario, incluso si no logró dar lugar a la revolución que sus creyentes esperaban, es decir, el comunismo, o más precisamente: el criptocomunismo.

https://confoederatio.noblogs.org/post/2020/10/04/criptocomunismo/ |

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

7 a 21 de 36

Siguiente Anterior

7 a 21 de 36

Siguiente Último

Último

|

Kramgasse street

Kramgasse street Bern clock tower in the old town

Bern clock tower in the old town The Bern clock tower at night

The Bern clock tower at night Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here

Outside of the Bern Historical Museum, a Bern Museum you can visit on a trip here Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)

Outside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern) Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)

Inside Einstein’s House (picture courtesy of AEG Bern)