|

|

General: ¿LOS NAZIS FUERON PIONEROS EN LOS VIAJES ESPACIALES?

Elegir otro panel de mensajes |

|

|

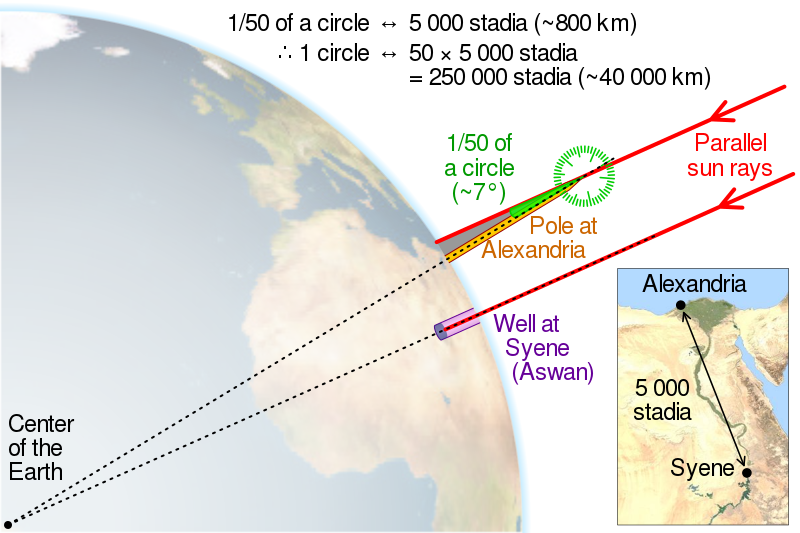

El 3 de octubre de 1942 un trueno rasgó el cielo en una base secreta de la Alemania nazi, cerca de localidad de Peenemünde. Bajo la atenta mirada de un nutrido grupo de ingenieros y científicos, un cohete A-4 («Aggregat 4»), de 12 toneladas de peso, rugió y despegó de su plataforma. El artefacto se elevó con decisión hacia las alturas, como si estuviera suspendido por una fuerza fantasmal. El furioso motor, alimentado con alcohol etílico y oxígeno líquido, le hizo viajar 190 kilómetros y elevarlo hasta los 38 kilómetros de altura.

Europa estaba luchando furiosamente en la Segunda Guerra Mundial cuando, sin que nadie lo sospechara, la carrera espacial dio su primer paso. Un 20 de junio de 1944 uno de estos cohetes A-4 atravesó la línea de Karmán, un límite situado a 100 kilómetros de altura, y llegó al espacio exterior, por primera vez en la historia. Pero su desarrollo no estaba motivado por el amor a la ciencia. En septiembre de ese mismo mes, los nazis comenzaron a lanzar cohetes A-4 cargados con explosivos sobre ciudades como Lieja, Amberes y Londres para vengarse por los bombardeos aliados sobre las ciudades alemanas. Acababa de nacer el misil balístico y el A4 se había convertido en el V-2 o «Vergeltungswaffe 2», «Arma de la venganza 2». Su destino era matar y fue construido con mano de obra esclava en campos de concentración, pero fue absolutamente crucial en el desarrollo de los cohetes espaciales. La prueba más directa es que su desarrollador, el ingeniero alemán Wernher Von Braun, fue también el «héroe» de los Estados Unidos de América que diseñó el cohete que llevó al hombre a la Luna.

Estragos causados por un misil V-2 en el barrio de Whitechapel, Londres, el 27 de marzo de 1945. El cohete mató a 134 personas - Imperial War Museum

«A pesar de lo deplorable que pueda resultar, los primeros pasos de la carrera espacial fueron un producto de la Guerra Fría y la carrera de armamentos», escribió Alan J. Levine en su obra «The missile and space race». «La mayoría de los cohetes que hicieron posible llegar al espacio fueron misiles militares modificados».

Los pioneros del espacio comenzaron su labor haciendo la guerra. Los principales diseñadores del monstruoso cohete soviético «R-7», que puso en órbita el Sputnik, el primer satélite artificial, diseñaron aviones de combate y lanzacohetes durante la contienda mundial. En los Estados Unidos, decenas de científicos del régimen nazi permitieron que el hombre llegara a la Luna con el programa Apolo. Y antes de eso, durante los años treinta, el recién nacido Laboratorio Aeronáutico Guggenheim en el Caltech (GALCIT) trabajó en aplicaciones militares para los misiles antes de convertirse en el famoso Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro (JPL), ya en 1944. La propia NASA, hoy el emblema de la exploración espacial, nació en 1958 con el objetivo de luchar contra el aplastante dominio soviético del espacio.

A pesar de que tanto en los Estados Unidos como en la Unión Soviética importantes científicos como Robert Goddard y Sergei Korolev, erigieron la base de la ciencia de los cohetes, el punto de partida de las primeras naves espaciales es el misil de guerra alemán V-2. Este cohete fue fruto del trabajo de Herman Oberth y, sobre todo, de un joven físico llamado Wernher Von Braun, quien encontró en el regimen nazi un medio para financiar y trabajar en el desarrollo de los cohetes. Von Braun, que ostentó un cargo en las infames y criminales SS («Schutzstaffel»), estuvo al frente de la parte tecnológica en la base secreta de Peenemünde y fue crucial para el éxito de los primeros diseños. Su impresionante labor le convirtió en la posguerra en un científico clave en el programa Apolo.

Wernher Von Braun, rodeado de los líderes nazis de los que dependieron los trabajos en la base secreta de Peenemünde - Bundesarchiv

V-2: El arma de la venganza

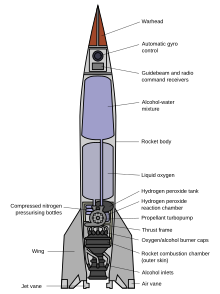

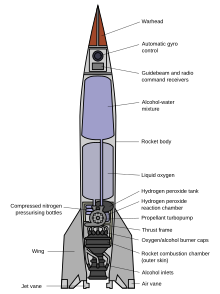

Con sus 14 metros de altura y su potente motor el V-2 era capaz de transportar una carga de 1.000 kilogramos de explosivo a 300 kilómetros de distancia. Iba provisto con giroscopios para controlar el rumbo, con una escasa precisión que solo mejoró a medida que avanzó la guerra. Sin embargo, volaba tan rápido que resultaba imposible de interceptar para los medios de la época: alcanzaba velocidades de hasta 5.760 kilómetros por hora y podía impactar a casi 3.000 km/h.

Misil V-2 en la actualidad - WIKIPEDIA

Tal como explica Javier Casado Pérez en «Historia y Tecnología de la Exploración Espacial», el mal desarrollo de la guerra llevó a Hitler a ordenar la producción en masa de los cohetes V-2. Desde septiembre de 1944 hasta la capitulación final, los alemanes construyeron más de 10.000 cohetes V-2, de las cuales 2.676 cayeron sobre ciudades aliadas provocando el pánico y la muerte de 9.000 personas.

Un misil para sembrar el terror

A diferencia de las otras armas, como la famosa bomba volante V-1, mucho más lenta y que podía ser interceptada, era imposible avisar de la llegada de uno de estos misiles, entre otras cosas porque solo hacían falta alrededor de cinco minutos para que el artefacto llegara al blanco después de su lanzamiento.

«De repente, hubo una gran explosión y una nube de escombros se levantó hacia el cielo en una carretera cercana. Era un V-2. Era un arma aterradora, no la oías acercarse, de repente llegaba y... ¡bang!», explicó un testigo, según recogió BBC.com.

El primer ataque sobre Londres, producido el 8 de septiembre de 1944, dejó un cráter de 10 metros de diámetro, mató a tres personas e hirió a 22. Animados por sus efectos sobre la población, los jerarcas nazis se pusieron el objetivo de producir 10.000 de estos cohetes y de lanzar 350 misiles a la semana. Mientras tanto, cientos de bombarderos británicos y estadounidenses arrasaban las ciudades alemanas en una carrera hacia la destrucción total.

Al principio, los daños causados por los V-2 fueron escasos a causa de la mala precisión de las armas. Pero aún así, el gobierno británico quiso evitar el pánico alegando que las explosiones eran causadas por problemas en las instalaciones de gas, así que los ingleses, con su proverbial sentido del humor, comenzaron a referirse a las V-2 como «cañerías de gas volantes» o «flying gas pipes».

Un arma construida por esclavos

Los ataques de las V-2 sobre las ciudades acabó resultando letal, pero los trabajos forzados y la esclavitud a los que el regimen nazi recurrió para construirlas dejó aún más víctimas.

El destino de miles de personas se selló en octubre de 1943, cuando los británicos lanzaron un bombardeo masivo sobre la base secreta de Peenemünde. En consecuencia, los alemanes trasladaron la producción de los cohetes a una gran base subterránea, cercana a Nordhausen.

Allí, acabaron empleando a 60.000 personas que se convirtieron en trabajadores esclavos, según «Dora.uah.edu». Se calcula que murieron entre 12.000 o 20.000 prisioneros en la construcción, según «V2rocket.com». En teoría, por cada V-2 fabricado fallecieron seis trabajadores esclavos.

Trabajadores esclavos trabajando en un misil V-2 - Hanss Peter-Frentz/Amicale des déportés de Dora-Ellrich/http://dora.uah.edu

«Es algo que con frecuencia se pasa por alto, pero no debería», dijo en BBC.com Doug Millard, historiador en el Museo de Ciencia de Londres. «El programa V-2 fue enormemente caro en términos de vidas, porque los nazis usaron mano de obra esclava para fabricar estos cohetes».

Una vida en condiciones «bárbaras»

En el libro «Dora», el autor Jean Michel relata cómo era la vida en las factorías donde se contruían los V-2. Allí recuerda las memorias de Albert Speer, ministro de armamentos del III Reich, en las que el líder nazi se refería así a los operarios: «Con el rostro carente de expresión, me miraban sin verme y se quitaban mecánicamente su gorro de preso de terliz azul hasta que nuestro grupo hubo pasado... Las condiciones de vida de aquellos presos eran verdaderamente bárbaras y me invade un sentimiento de profunda consternación y de culpabilidad».

Los trabajadores provenían de otros campos de concentración donde las condiciones eran probablemente peores. Los nazis, queriendo aprovechar las habilidades técnicas de sus prisioneros, como la capacidad de soldar, internaron a sus esclavos en la inmensa factoría subterránea de Mittlebau, Mittlewerk o campo Dora, cerca del campo de concentración de Buchenwald (aquí hay un mapa del enorme complejo).

Allí, los prisioneros construían las piezas del V-2, producían oxígeno líquido, combustible sintético y otras armas experimentales. Los trabajadores esclavos no veían la luz del sol, dormían poco, recibían una pobre alimentación y las condiciones sanitarias en las que vivían eran deplorables. Muchos fueron ejecutados por intento de sabotaje y fueron colgados en las grúas que había sobre las líneas de producción, tal como relata «V2rocket.com».

|

|

|

|

|

www.expresionculturarte.com › ... › MUNDO DE LAS PSEUDOCIENCIAS

Un 20 de junio de 1944 uno de estos cohetes A-4 atravesó la línea de Karmán, un límite situado a 100 kilómetros de altura, y llegó al espacio exterior, por primera vez en la historia. Pero su desarrollo no estaba motivado por el amor a la ciencia. En septiembre de ese mismo mes, los nazis comenzaron a lanzar cohetes ...

https://www.newslatina.net/.../73583-un-cohete-inventado-por-los-nazis-el-primer-arte...

Mientras Europa se desangraba en la Segunda Guerra Mundial, el 20 de junio de 1944 uno de estos cohetes atravesó la línea de Karman, a 100 kilómetros de altura, y llegó al espacio exterior, por primera vez en la historia humana. En septiembre de ese mismo mes, los cohetes A-4 comenzaron a lanzarse en masa sobre ...

|

|

|

|

|

1. Jueces 20:31 Y salieron los hijos de Benjamín al encuentro del pueblo, alejándose de la ciudad; y comenzaron a herir a algunos del pueblo, matándolos como las otras veces por los caminos, uno de los cuales sube a Bet-el, y el otro a Gabaa en el campo; y mataron unos treinta hombres de Israel. 2. Marcos 15:21 Y obligaron a uno que pasaba, Simón de Cirene, padre de ALEJANDro y de Rufo, que venía del campo, a que le llevase la cruz.

3. Hechos 4:6 y el sumo sacerdote Anás, y Caifás y Juan y ALEJANDro, y todos los que eran de la familia de los sumos sacerdotes;

4. Hechos 6:9 Entonces se levantaron unos de la sinagoga llamada de los libertos, y de los de Cirene, de ALEJANDría, de Cilicia y de Asia, disputando con Esteban.

5. Hechos 18:24 Llegó entonces a Efeso un judío llamado Apolos, natural de ALEJANDría, varón elocuente, poderoso en las Escrituras.

6. Hechos 19:33 Y sacaron de entre la multitud a ALEJANDro, empujándole los judíos. Entonces ALEJANDro, pedido silencio con la mano, quería hablar en su defensa ante el pueblo.

7. Hechos 27:6 Y hallando allí el centurión una nave ALEJANDrina que zarpaba para Italia, nos embarcó en ella.

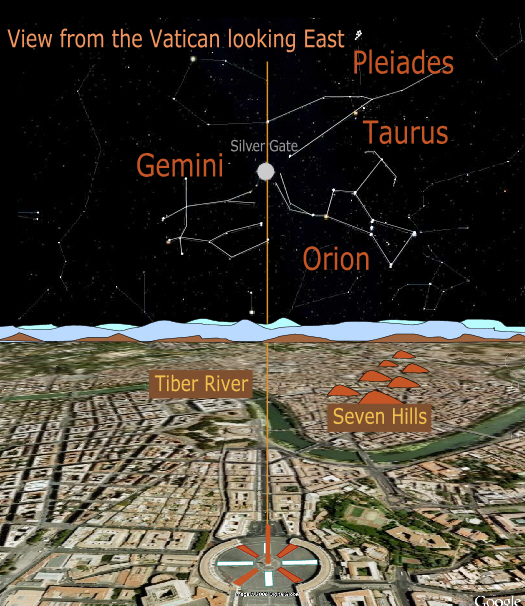

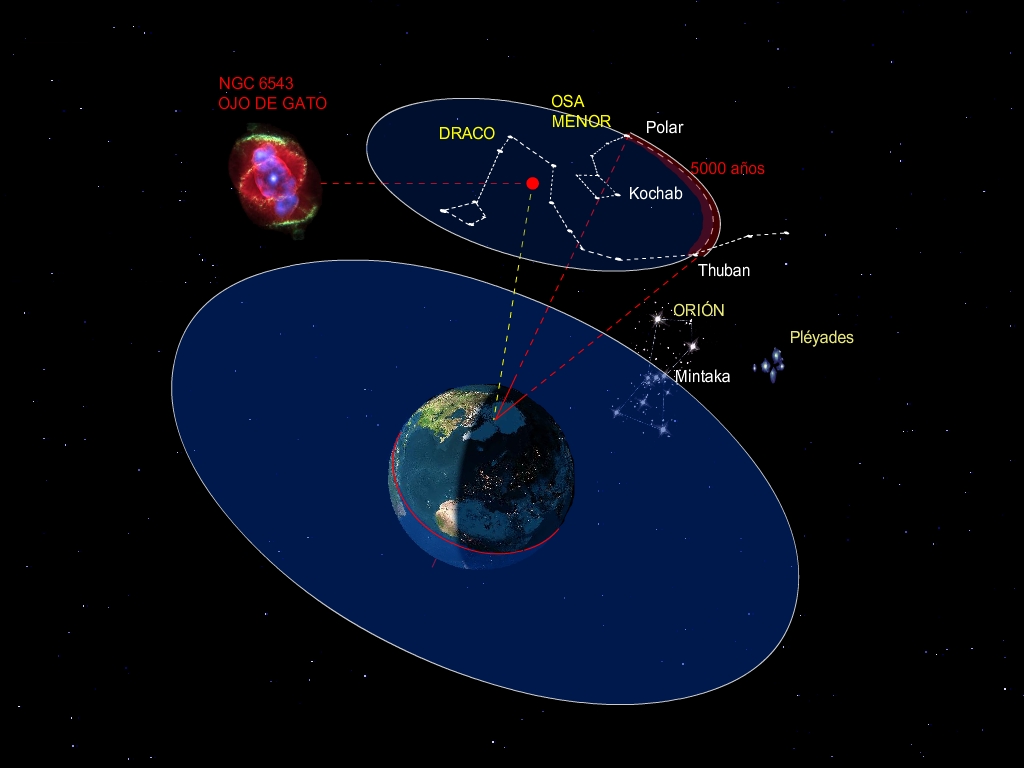

8. Hechos 28:11 Pasados tres meses, nos hicimos a la vela en una nave ALEJANDrina que había invernado en la isla, la cual tenía por enseña a Cástor y Pólux. (CASTOR Y POLUX, OSEA LA CONSTELACION DE GEMINIS-NEXO 911)

9. 1 Timoteo 1:20 de los cuales son Himeneo y ALEJANDro, a quienes entregué a Satanás para que aprendan a no blasfemar.

10. 2 Timoteo 4:14 ALEJANDro el calderero me ha causado muchos males; el Señor le pague conforme a sus hechos.

ALEJANDRIA (SEDE DE LA IGLESIA COPTA CUYO PATRONO ES EL MISMO JUAN MARCOS Y CUYO CALENDARIO COMIENZA JUSTAMENTE EL 11 DE SEPTIEMBRE O 911) |

|

|

|

|

Hechos 28

1. Estando ya a salvo, supimos que la isla se llamaba Malta.

2. Y los naturales nos trataron con no poca humanidad; porque encendiendo un fuego, nos recibieron a todos, a causa de la lluvia que caía, y del frío.

3. Entonces, habiendo recogido Pablo algunas ramas secas, las echó al fuego; y una víbora, huyendo del calor, se le prendió en la mano.

4. Cuando los naturales vieron la víbora colgando de su mano, se decían unos a otros: Ciertamente este hombre es homicida, a quien, escapado del mar, la justicia no deja vivir.

5. Pero él, sacudiendo la víbora en el fuego, ningún daño padeció.

6. Ellos estaban esperando que él se hinchase, o cayese muerto de repente; mas habiendo esperado mucho, y viendo que ningún mal le venía, cambiaron de parecer y dijeron que era un dios.

7. En aquellos lugares había propiedades del hombre principal de la isla, llamado Publio, quien nos recibió y hospedó solícitamente tres días.

8. Y aconteció que el padre de Publio estaba en cama, enfermo de fiebre y de disentería; y entró Pablo a verle, y después de haber orado, le impuso las manos, y le sanó.

9. Hecho esto, también los otros que en la isla tenían enfermedades, venían, y eran sanados;

10. los cuales también nos honraron con muchas atenciones; y cuando zarpamos, nos cargaron de las cosas necesarias.

11. Pasados tres meses, nos hicimos a la vela en una nave alejandrina que había invernado en la isla, la cual tenía por enseña a Cástor y Pólux.

12. Y llegados a Siracusa, estuvimos allí tres días.

13. De allí, costeando alrededor, llegamos a Regio; y otro día después, soplando el viento sur, llegamos al segundo día a Puteoli,

14. donde habiendo hallado hermanos, nos rogaron que nos quedásemos con ellos siete días; y luego fuimos a Roma,

15. de donde, oyendo de nosotros los hermanos, salieron a recibirnos hasta el Foro de Apio y las Tres Tabernas; y al verlos, Pablo dio gracias a Dios y cobró aliento.

16. Cuando llegamos a Roma, el centurión entregó los presos al prefecto militar, pero a Pablo se le permitió vivir aparte, con un soldado que le custodiase.

17. Aconteció que tres días después, Pablo convocó a los principales de los judíos, a los cuales, luego que estuvieron reunidos, les dijo: Yo, varones hermanos, no habiendo hecho nada contra el pueblo, ni contra las costumbres de nuestros padres, he sido entregado preso desde Jerusalén en manos de los romanos;

18. los cuales, habiéndome examinado, me querían soltar, por no haber en mí ninguna causa de muerte.

19. Pero oponiéndose los judíos, me vi obligado a apelar a César; no porque tenga de qué acusar a mi nación.

20. Así que por esta causa os he llamado para veros y hablaros; porque por la esperanza de Israel estoy sujeto con esta cadena.

21. Entonces ellos le dijeron: Nosotros ni hemos recibido de Judea cartas acerca de ti, ni ha venido alguno de los hermanos que haya denunciado o hablado algún mal de ti.

22. Pero querríamos oír de ti lo que piensas; porque de esta secta nos es notorio que en todas partes se habla contra ella.

23. Y habiéndole señalado un día, vinieron a él muchos a la posada, a los cuales les declaraba y les testificaba el reino de Dios desde la mañana hasta la tarde, persuadiéndoles acerca de Jesús, tanto por la ley de Moisés como por los profetas.

24. Y algunos asentían a lo que se decía, pero otros no creían.

25. Y como no estuviesen de acuerdo entre sí, al retirarse, les dijo Pablo esta palabra: Bien habló el Espíritu Santo por medio del profeta Isaías a nuestros padres, diciendo:

26. Ve a este pueblo, y diles:

De oído oiréis, y no entenderéis;

Y viendo veréis, y no percibiréis;

27. Porque el corazón de este pueblo se ha engrosado,

Y con los oídos oyeron pesadamente,

Y sus ojos han cerrado,

Para que no vean con los ojos,

Y oigan con los oídos,

Y entiendan de corazón,

Y se conviertan,

Y yo los sane.

28. Sabed, pues, que a los gentiles es enviada esta salvación de Dios; y ellos oirán.

29. Y cuando hubo dicho esto, los judíos se fueron, teniendo gran discusión entre sí.

30. Y Pablo permaneció dos años enteros en una casa alquilada, y recibía a todos los que a él venían,

31. predicando el reino de Dios y enseñando acerca del Señor Jesucristo, abiertamente y sin impedimento.

|

|

|

|

|

. Juan 16:21 La mujer cuando da a luz, tiene dolor, porque ha llegado su HORA; pero después que ha dado a luz un niño, ya no se acuerda de la angustia, por el gozo de que haya nacido un hombre en el mundo.

|

|

|

|

|

NE-CESAR-IO

C-SAR

S=CONSTELACION DE DRACO=$ = SARA (ESPOSA DE ABRAHAM)= GALATAS 4:26

DRACO=S-ARA

|

|

|

|

|

La Puerta de Istar (o de Ishtar) fue una de las 8 puertas monumentales (10 metros de altura por 14 de ancho) de la muralla interior de Babilonia, a través de la cual se accedía al templo de Marduk, donde se celebraban las fiestas del año nuevo. El nombre de Istar lo recibe de la diosa a la que estaba consagrada.1

Fue construida en el año 575 a. C. por Nabucodonosor II en el lado norte de la ciudad.1 Se compone de adobe y cerámica vidriada, la mayoría de color azul debido al lapislázuli (lo que la hacía contrastar fuertemente con todos los edificios de su alrededor), mientras que otros son dorados o rojizos. Estos últimos se disponen dibujando la silueta de dragones, toros, leones y seres mitológicos. La parte inferior y el arco de la puerta están decorados por filas de grandes flores semejantes a margaritas. La Puerta de Istar contaba también originariamente con dos esfinges dentro del arco de la puerta, que se han perdido hoy en día.

Los restos de la puerta original fueron descubiertos en Babilonia durante las campañas arqueológicas alemanas de 1902 a 1914.1 La mayoría se trasladó a Alemania, donde se reconstruyó la puerta en el Museo de Pérgamo de Berlín, en 1930, lugar en el que actualmente se expone. Algunos de los relieves originales de leones, dragones y toros se encuentran actualmente en el Museo Arqueológico de Estambul, el Instituto de Artes de Detroit, el Museo Metropolitano de Arte de Nueva York, el Instituto Oriental de Chicago, el Museo de la Escuela de Diseño de Rhode Island y el Museo de Bellas Artes de Boston.

Durante el gobierno de Saddam Hussein en Irak, se comenzaron a reconstruir grandes zonas de la vieja Babilonia, entre ellas la Puerta de Istar, cuya réplica se levantó sobre el antiguo emplazamiento de la original. El plan era convertirla en la puerta de acceso a un nuevo museo arqueológico iraquí que nunca llegó a construirse. Actualmente, la réplica se encuentra bajo la responsabilidad de la 155ª Brigada de Combate del Ejército de Estados Unidos, cuyo campamento se encuentra dentro de las murallas de Babilonia.

|

|

|

|

|

Pete «Black Thunder»

El rostro de Adolf Hitler cambió. Sus ojos se abrieron asombrados. En sus labios podía verse una expresión de fascinación y tensión: «Cuando le describimos nuestros logros, su cara se iluminó de entusiasmo», afirmó Von Braun, que dirigía el proyector con el que pasaba las imágenes del exitoso lanzamiento del cohete A-4. Un proyectil disparado hacia los confines del mundo conocido, un invento que pondría a Alemania al frente de la tecnología casi de ciencia ficción soñada por Julio Verne. Un arma, en definitiva. Von Braun, un aristócrata y nazi convencido seguidor de Verne y H. G. Wells, soñaba con hacer realidad su proyecto de toda la vida: alcanzar la Luna, aunque para ello volase el mundo por los aires. Aquel cohete sería el principio del fin de una ciudad de Londres que sería castigada duramente con atroces bombardeos. El arma total.

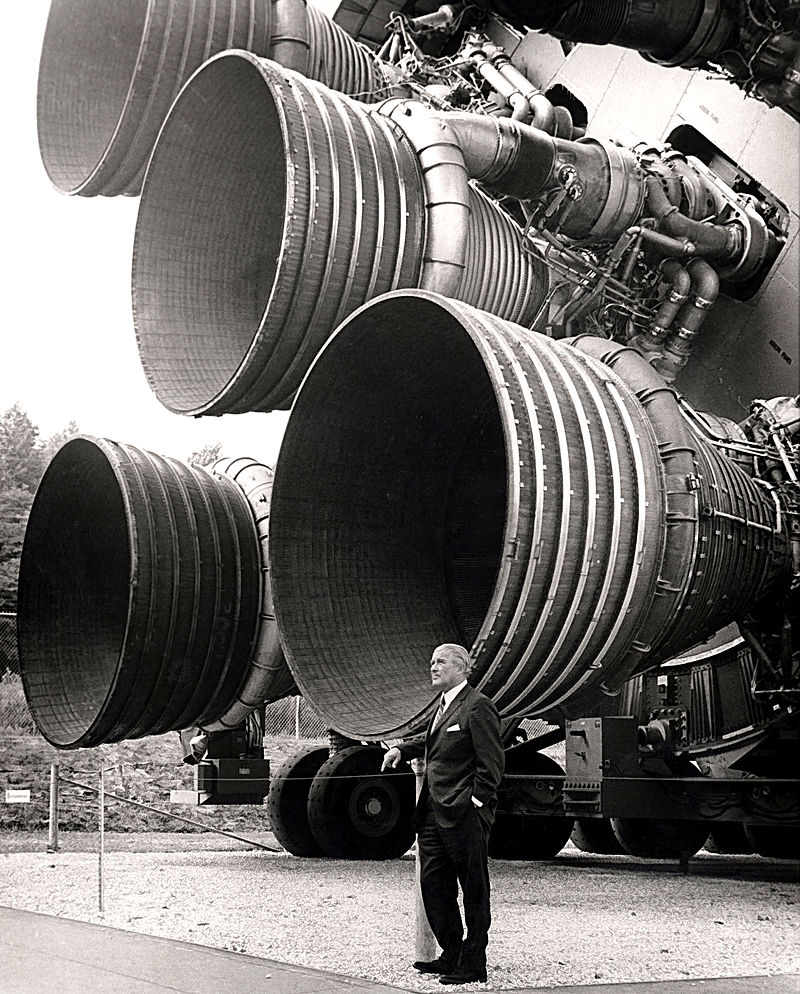

VON BRAUN, TRAJEADO, JUNTO A DIRIGENTES NAZIS

Hitler, que había visto in situ, en su famosa «guarida del lobo», las posibilidades de aquel invento, estaba convencido. Apoyaría los planes de Von Braun y, por vez primera, echaría a un lado sus supersticiones, cuando soñase que ningún cohete podría alcanzar jamás Inglaterra. Los sueños erraban. Von Braun, que trabajó con ahínco en las armas que arrasarían las ciudades inglesas, era un mesías tecnológico. «¡La humanidad no podrá soportarlo!», añadió Hitler.

Es muy poco conocido que, en octubre de 1939, los científicos nazis ya habían lanzado un cohete que alcanzó los 95 kilómetros de altura, quedándose muy cerca de la línea de Kármán, que al llegar a los 100 kilómetros marca la frontera entre la atmósfera terrestre y el espacio exterior. En aquel momento, con la guerra mundial desatada, los nazis se situaban en primera posición en la experimental carrera aeroespacial, muy lejos aún de los primeros intentos soviéticos.

El escenario, al terminar la guerra, era otro bien distinto. Europa estaba destruida y Hitler había muerto. Los nazis estaban siendo perseguidos y, a veces, cuando caían en las garras de los cazanazis, eran juzgados o directamente eliminados. Von Braun, que se sabía buscado, no dudó en cruzar el charco y llegar hasta el supuesto país de las libertades, el adalid del antifascismo, Estados Unidos. Con el Ejército Rojo a las puertas de Berlín, el 19 de marzo de 1945, se dictó la «Orden Nerón», por la cual «cualquier cosa [...] de valor situada en el territorio del Reich, que pueda ser empleada por el enemigo de inmediato o en un futuro próximo para la continuación de la guerra, ha de ser destruida». Lo de «cosas» era extensible a personas como Von Braun, que temía ser asesinado antes de caer en manos soviéticas o americanas, que sabían de sus capacidades asombrosas en la temprana carrera aeroespacial. Así que huyó con lo puesto disfrazado de soldado raso alemán.

VON BRAUN, CON UN BRAZO ESCAYOLADO A CAUSA DE UN ACCIDENTE DE COCHE, EN EL MOMENTO DE ENTREGARSE A LAS AUTORIDADES AMERICANAS

La Unión Soviética y Estados Unidos lucharon por atraparlo, pero no para que fuese juzgado sino para incorporarlo a sus planes de conquista espacial. Las preferencias del nazi estaban claras: Estados Unidos seguía siendo una potencia económica de primer orden, ya que la guerra no la había destruido y, en el futuro, lideraría la obsesión espacial. Se puso a sus servicios y los americanos, encantados, organizaron su traslado y su futura vida.

Lo primero que se hizo fue maquillar su identidad gracias a una operación con un nombre absolutamente adecuado: «Paperclip» («Sujetapapeles»), que básicamente manipulaba biografías para presentarlas «civilizadas» ante el pueblo americano. Von Braun, de este modo, era un hombre nuevo, un científico alemán que jamás había colaborado en el exterminio. De la noche a la mañana, estaba en El Paso, Texas, y contaba con un equipo científico a su servicio, además de su familia.

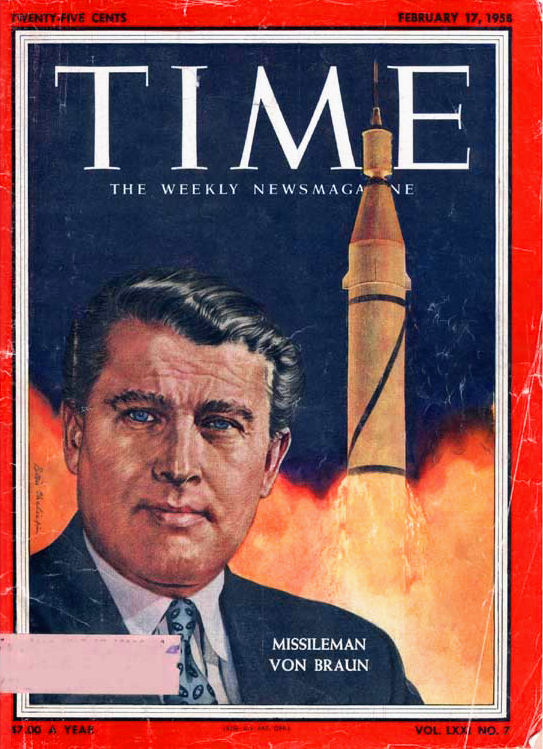

EL RENOVADO VON BRAUN COMO RESPETABLE CIENTÍFICO

Pero pasaron los años y los sueños de Von Braun parecían esfumarse. El mundo cambiaba y quizá jamás llegaría a convencer al presidente de la conveniencia de financiar algo tan increíblemente costoso como situar al primer americano en la Luna. Sin embargo, todo cambió cuando por vez primera en la historia los rusos lograron enviar un hombre al espacio, Yuri Gagarin, el 12 de abril de 1961. Varias semanas más tarde, un grandilocuente John F. Kennedy se dirigió al Congreso en un discurso retransmitido y afirmó que, desde esa fecha, el objetivo supremo sería alcanzar la Luna. Todos los americanos debían colaborar para alcanzar el objetivo, ya que si lo conseguían los pérfidos rusos, impondrían el soviet en la tierra.

VON BRAUN PASEANDO JUNTO A KENNEDY EN MAYO DE 1963

Así nació el programa Apolo, que resucitó de inmediato a un ahora exultante Von Braun, para quien había llegado su gran momento. «Paperclip» se transformó en programas televisivos en los que siempre podía verse el «simpático» rostro de Von Braun.

VON BRAUN JUNTO A CINCO MOTORES F-1

Su nombre también pasó a ser parte de la vida cotidiana a través de su participación en tres programas de televisión de Walt Disney dedicados a la exploración espacial, donde era presentado como un pacífico soñador y un idealista del espacio.

Su biografía, que seguía esta línea, se tituló Mi vida para la navegación espacial. También la revista Collier publicó artículos en los que ensalzaba su figura. Von Braun encajaba en la campaña de Disneylandia, basada en varias ideas: Fantasyland, Frontierland, Adventureland y Tomorrowland. Los sueños aeroespaciales llenaban la imaginación de los niños americanos. En 1955, por ejemplo, Walt Dysney produjo el primer gran programa sobre este tema, que llamó Man in space (donde colaboró Von Braun) y que, por supuesto, fue todo un éxito. Walt Disney se embarcó completamente en el Marshall Space Flight Center, dirigido por el antiguo nazi.

","url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2fautyLuuvo","resolvedBy":"youtube","overlay":false,"floatDir":null,"providerName":"YouTube","description":{"html":"VON BRAUN EXPLAIN A FUTUR VISION OF SPACE ORBITAL MISSION WITH SPACE SHUTTLE ROCKET. A POSITIVE PROPAGATING FOR HUMAN VOYAGE INTO SPACE WITH WALT DISNEY COM."}}" data-block-type="32" id="block-yui_3_17_2_5_1457775745569_15440" style="position: relative; height: auto; padding: 12px 17px; clear: both;">

" id="yui_3_17_2_1_1727140114581_75" style="position: absolute; top: 0px; left: 0px; width: 711px; height: 533.25px;">

Von Braun, que disponía de fondos ilimitados, trabajó de forma titánica hasta poner a punto su cohete que, el 16 de junio de 1969, logró disparar hacia el infinito, en una célebre cuenta atrás inspirada en la película de Fritz Lang, La mujer en la luna, (1929), una de sus favoritas. El propio Von Braun encargó que en la base del primer misil que lanzó, en los tiempos del nazismo, se pintase el logo de la película.

","url":"https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nkiRCNMq_Es","resolvedBy":"youtube","overlay":false,"floatDir":null,"providerName":"YouTube","description":{"html":"Some nice and funky early special effects in this scene from Fritz Lang's underrated science fiction classic "Woman In The Moon" (Frau Im Mond) from 1929 (A.K.A. "rocket to the moon"). This was Lang's last silent movie. Featuring the talents of Willy Fritsch, Gerda Maurus and Fritz Rasp, among others."}}" data-block-type="32" id="block-yui_3_17_2_5_1457775745569_14245" style="position: relative; height: auto; padding: 12px 17px; clear: both;">

" id="yui_3_17_2_1_1727140114581_119" style="position: absolute; top: 0px; left: 0px; width: 711px; height: 533.25px;">

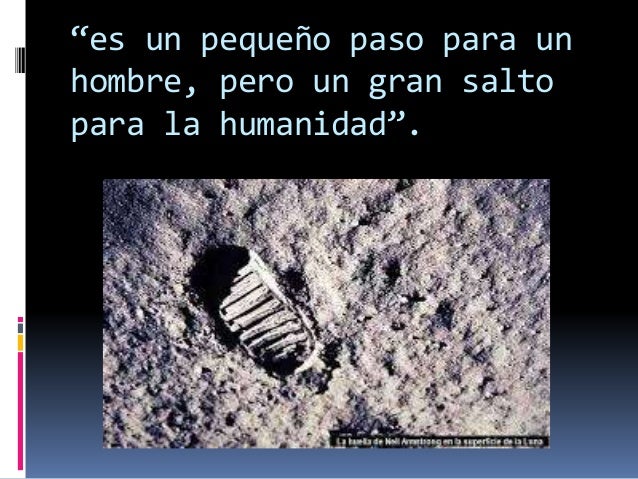

Neil Armstrong puso un pie en suelo lunar. El viejo oligarca nazi cumplía el sueño de su vida. Von Braun era ya uno de los personajes más famosos y valorados del país. Vivió a todo lujo hasta 1976, año en que falleció en Maryland.

http://www.agenteprovocador.es/publicaciones/los-nazis-en-la-luna |

|

|

|

|

ESSAY HISTORYUSA January 11, 2019

V-2 and Saturn V: A Tale of Two Rockets

What does it mean that the same men who built a deadly rocket for the Nazis helped get America to the moon?

By Patrick HicksShareE-mail

Bumper V-2 launch, July 1950. Photo: NASA. “The rocket will free man from his remaining chains, the chains of gravity which still tie him to this planet. It will open to him the gates of heaven.”

—Wernher von Braun

The world’s first functional long-range ballistic rocket, the V-2, weighed almost 28,000 pounds and could rumble fifty miles up into the crisp unexplored atmosphere. It was so technologically advanced that Nazi Germany became the first country to put an object made by human hands into space. During one particular test in the summer of 1944, launching from an island on the Baltic Coast called Greifswalder Oie, their rocket soared past the “Kármán Line”—which, in marking the boundary between our world and the black void beyond, puts the beginning of space at 100 kilometers above sea level, or roughly sixty-two miles straight up—by almost fifty miles. But the Nazis weren’t interested in setting altitude records. They only cared about height, so that the V-2 could arc over the top of a deadly parabola and then scream its way back down toward earth, where it would punch holes into cities hundreds of miles away. The V-2 was never designed to stay up in the heavens. It was designed to fall.

This Nazi rocket was essentially just an enormous projectile that didn’t require a cannon. A button was pushed, fuel ignited in blinding fury, and off it went into the clouds. The V stood for Vergeltungswaffe, or “vengeance weapon.” For its victims, it blew open the door to the next world. The V-2 was the brainchild of a young man named Wernher von Braun. Quick with a smile, he made parties sparkle with laughter and was known as something of a ladies’ man. Though only in his twenties, von Braun knew how to organize, how to charm, and—most importantly—how to turn blueprints into realities. He was the center of gravity for the V-2 program at Peenemünde: all major decisions orbited around him, and he made sure his rockets hit their intended targets. Von Braun joined the Nazi party in 1937, and three years later, Heinrich Himmler personally invited him to join the SS. Although von Braun accepted this commission, he would spend the rest of his life bending attention away from his involvement with the same organization that ran Dachau, Treblinka, and Auschwitz.

At first, Hitler was totally unimpressed with the V-2. He saw it as simply a massive artillery shell with an extremely long range. But as Germany began to lose the war, he slowly warmed to the idea. He wanted to punish the Allies by turning their pretty little cities into smoldering wastelands. On a July evening in 1943, von Braun dimmed the lights in an underground bunker and showed the Führer a silent movie of a V-2 taking off. As the film splashed life against a concrete reinforced wall, Hitler sat slumped in a wooden chair, a black cape draped over his shoulders. He watched as, in brilliant color, a rocket shot into the sky on a mute flame, then arced away at three times the speed of sound. Hitler beamed and jumped to his feet. He wanted to know what the “annihilating effect” of the warhead might be, and apologized that he hadn’t believed in the project sooner. Clapping his hands together, he made the young SS officer a professor on the spot. It was a rare honor. Within days, an order was given for thousands of V-2s to be built. The goal was to launch them like locusts towards New York and Washington, D.C. In time, maybe they could even reach Chicago.

After the war, when fame tapped him on the shoulder and he became the smiling face of America’s fledgling space program, von Braun made sure to downplay his involvement in the darker aspects of this effort. He talked instead about blueprints. He focused on gyroscopes, propellant, and lift. It wouldn’t be the last time he would obsess about such things, nor would it be the last time he would help make the impossible possible. In two short decades, von Braun would stand on the Florida coastline, part of another event that would shake the world’s understanding of reality.

*

After American and British bombers pulverized the existing plant at Peenemünde, German rocket assembly moved underground. Rather than rebuild a factory that could be hit again, the Nazis decided that everything should be hidden beneath a mountain. And so it was that they created a secret underground concentration camp. They marched skeletal prisoners into an old gypsum mine and ordered them to make it bigger. The prisoners plugged dynamite into rock, and blasted tunnels into a stubby mountain range called the Kohnstein. SS- Sturmbannführer Wernher von Braun visited the underground factory several times—he worked in an office just eleven miles away—and although he would later say the working conditions were “hellish” in the tunnels, he apparently had no qualms about using slave labor to advance his career. Few Nazis did.

The official name of the camp was Dora-Mittelbau, and it was built less than ten kilometers from the city of Nordhausen. Resting in the north of the Thuringia district, Nordhausen was graced with medieval architecture, a fine cathedral, and—before the war changed so many things—it was a proud city that had stood for over a thousand years. It was home to distilleries, breweries, and factories that made transportation equipment. At night, people gathered in restaurants to drink a popular beverage called korn, which is made from fermented rye. Swastika banners hung in the streets and the radio delivered good news about the future that Hitler was bringing to the nation. At first, the good news seemed unending: the annexation of the Sudetenland, the Anschluss of Austria, the conquest of Poland, and through it all, mighty England seemed powerless. And then the Führer truly outdid himself; he conquered France in less than two months. It seemed impossible. Something that years of bloody trench warfare had failed to accomplish between 1914 and 1918 had been achieved in just six short phases of the moon. After the invasion of the Soviet Union, however, the good news didn’t seem quite so frequent. If anything, the war seemed to be turning. Broadcasting from Berlin’s Sportpalast in February 1943, the Reich Minister of Propaganda, Dr. Joseph Goebbels, called for total war and promised that new “secret weapons” would soon be unleashed against the enemy.

Work began on the tunnels on August 28, 1943, when prisoners from the nearby concentration camp of Buchenwald were ordered to dig into a tough sedimentary rock known as anhydrite. It was so hard, in fact, that huge internal spaces wouldn’t need supporting beams. The Kohnstein was a natural fortress and it was obvious that American and British planes would never be able to bomb the assembly line of rockets hidden in its depths. Work on the tunnels accelerated, and by Christmas more than 10,000 prisoners were hammering and blasting their way into the Kohnstein. Deafening cracks of TNT sounded almost around the clock, dust particles filled up the prisoners’ lungs, and their blue-and-white striped uniforms were covered in fine powder.

The emaciated prisoners were ordered to clear away huge chunks of freshly dynamited rock. They tossed broken pieces into stubby rail cars known as grubenhunten. By sheer force of will, they muscled these carts down a track to a narrow-gauge locomotive, which pulled the stones out into the glare of the sun. These men—these expendable tools, these ghosts in waiting—were beaten if the grubenhunten were derailed or if they moved too slowly. There was no plumbing and the prisoners had to walk through streams of excrement. Not surprisingly, tuberculosis, typhoid, and pneumonia spread at fearsome rates. Withered men—husbands and fathers and sons—fell to the ground in unrelenting numbers. Still, the work continued.

To this day it’s unclear how many prisoners died building the tunnels, though the numbers are in the thousands. Their bodies were hauled away to Buchenwald, where they were burnt in a crematorium. As more prisoners were fed into the tunnels, the SS at Dora-Mittelbau requested their own oven for burning the dead; this wish was granted. Once the oven was fitted into place and fired to life, it didn’t take long before human ashes were tipped into a ravine that acted as a garbage dump.

By early 1944, both tunnels were finished, along with rail tracks that curved out from their gaping mouths. In all, some 35 million cubic feet of space had been gouged out of the Kohnstein to make way for the rocket assembly. Each tunnel was a mile long and two stories high. Think of Tunnel A and Tunnel B running parallel to each other with a gentle S curve to both. The two tunnels were linked by smaller tunnels. The world’s largest underground factory was finally ready for use, and the idea of the rocket was about to move from the realm of science fiction into the realm of science fact. What would soon roll out from this concentration camp would not only change the twentieth-century, it would rumble down the decades to come.

*

The V-2 had three different sections: the nosecone, which was packed with explosives and the navigation system; the center section, which held the propulsion system; and the engine, which had four tail fins around a nozzle to aid guidance and provide stability. The V-2s were assembled the same way that Henry Ford made his cars: each rocket moved down the tunnel and prisoners added parts as it inched for the exit. Near the end, the V-2s were painted olive green, laid down onto rail cars, and moved off to different locations across Germany. From there, maps were taken out. Coordinates were set. Countdowns began—five, four, three, two—and each rocket rumbled up into the blue. A column of smoke was all that remained as rocket after rocket curved for London, Brussels, Antwerp, and Paris.

But problems remained that prevented the V-2 from being mass-produced. In particular, Nazi scientists struggled with gyroscopes, turbo pump generators, and servomotors that moved the air vanes. These vanes proved especially tricky, because attempts at controlling something that was going several times the speed of sound were virtually unprecedented. How do you steer a bullet?

Although the missile could be launched from just about anywhere, the men in charge of these sleek messengers of death favored roads that ran through dense forests. After the rocket was placed on a mobile launcher known as a Meillerwagen, it could then be towed into a clearing, where it was propped upright and fired. Shortly after takeoff, the double-crack of a sonic boom could be heard for miles around. Bah-boom!

The V-2 entered English airspace at blistering speeds. No one knew it was coming.

And because the V-2 moved at nearly five times the speed of sound, air raid sirens all across London were suddenly useless. The rocket came straight down like a hammer. Upon impact, the warhead blasted a crater into the earth that was sometimes as wide as a bowling alley. Soil, brick, glass, and other debris fountained up. Moments later, ambulances and fire trucks whined awake. Smoke twisted up into the sky like a ghostly exclamation point. The rocket was no longer something of fantasy or the movies. It was now a weapon of mass murder.

*

A career soldier who had seen action in the Great War of 1914-1918, Walter Dornberger was a brilliant designer who held four patents in rocket development as well as an engineering degree from the Institute of Technology in Berlin. He was appointed to the Mittelbau Advisory Council in late 1943, where he thought up the mobile launch platforms that allowed individual V-2s to be moved around the countryside and therefore avoid detection from Allied bombers. After pacing the tunnels of Dora-Mittelbau himself, and being involved in crimes against humanity, Dornberger would go on to design high-performance aircraft for the United States. He would also play a significant role in the early development of the Space Shuttle. But before that, he and von Braun were honored at what had to have been one of the most unusual award ceremonies of the entire war.

It happened on December 9, 1944, at a place called Castle Varlar. This ancient monastery had been turned into a grand estate, and on this particular evening, the banquet hall was decorated with swastika flags, fine china, and silverware. Ivy was wrapped around a podium. A number of V-2s waited to be launched from the snowy gardens outside. Von Braun, Dornberger, and two other scientists were to be honored with the prestigious “Knight’s Cross,” and they wore tuxedos for the occasion. In between gourmet courses, the lights in the hall were shut off, a tall curtain at the end was pulled aside, and a V-2 was launched. Thunderous reverberations filled up the room as orange light from the exhaust flickered on the faces of the smiling men. The evening proceeded like this, alternating between food and firings.

Another important personality at Dora-Mittelbau was a man named Arthur Rudolph, who was in charge of production. Short and balding, he was von Braun’s right-hand man, making sure the V-2s were constructed properly and were rolling out of the tunnel at a steady clip. He didn’t care about prisoners dropping dead under his command; he only cared about quality control. He strolled through the tunnels to solve tricky engineering problems and, on at least one occasion, ordered production of the V-2s stopped so that all prisoners could watch a mass hanging. This was meant as a warning for anyone who might be thinking about sabotage.

As an enthusiastic Nazi, it was Rudolph’s job to make sure there was a constant supply of prisoners at Dora. His indifference to life is perhaps best exemplified by his reaction to being taken away from a lively New Year’s Eve party to solve a problem at the underground factory. With 1945 looming, a strap used to hold down the rockets wasn’t fitting properly. When he arrived at the tunnels, he realized there was nothing he could do until the morning. He didn’t notice the starving prisoners working around him at a fever pitch, nor did he care about the greasy black smoke that curled out of the crematorium. It’s possible that Arthur Rudolph stood outside Tunnel A on that evening, looked up at the moon, and wondered what the New Year would bring to him. Maybe, as he studied its bright celestial glow, he took long pulls from a bottle of champagne. A Chteau Lafite Rothschild, perhaps.

While we don’t know what Rudolph was thinking on that particular night, we do know that in the decades to come he, von Braun, and Dornberger would all become indispensable to America’s aerospace program. They would receive awards, honors, and ticker-tape parades. Their new country would welcome them. They would be showered with riches.

*

When the Americans discovered what was hidden at Dora-Mittelbau in April 1945, they packed up everything they could lay their hands on. Some 300 rail cars were loaded down with fuel tanks, fins, nosecones, servomotors, and engines. These pieces of the future were sent across the Atlantic to another secret camp: The White Sands Proving Grounds in New Mexico.

The V-2 was studied, examined, copied, and made better. On October 24, 1946, a camera was bolted to the side of the rocket and, as it roared up into the clear blue sky, snapped a photo every other second. It climbed to sixty-five miles (three miles above the Kármán Line) and took the very first photograph from space. The rocket tumbled back to Earth and smashed into the ground at a blazing 500 feet per second. Although the camera was destroyed, the film—encased in a heavy steel box—was not. The photo taken that day was grainy, yet the curvature of the earth can be seen clearly, along with a smudge of cloud. Scientists called it a “Rocket-Eye View” of the world. Nothing quite like it had ever been seen before.

The U.S. Army didn’t want the world to know about the technological wonders that had been found inside the mountain, so they kept the crimes against humanity that occurred at Dora classified. They believed the need for military secrecy was greater than the horrors that were committed. Propellant and sheet metal were given priority over blood and bone; certain numbers were given priority over others.

Design Specifications of the V-2:

Length: 45 feet, 11 inches

Diameter: 5 feet, 5 inches

Weight: 13.8 tons

Propellant: ethanol/water mixture and liquid oxygen Propellant Weight: 8,400 lbs.

Range: 200 miles

Peak altitude: 55 miles

Speed: 3,580 miles per hour Warhead: 2,200 lbs. of amatol

Number of Attacks:

1,696 on Belgium

1,403 on the United Kingdom 76 on France

19 on Holland

Number of Deaths due to V-2 Attacks:

5,500 (estimated)

Number of Deaths at Dora-Mittelbau:

20,000 (estimated)

Within months of World War II ending, a secret program called “Operation Paperclip” brought hundreds of Nazi administrators, chemists, and engineers to the United States. The numbers these men had locked in their heads were keys to new frontiers and new possibilities. And because their knowledge was in danger of falling into Russian hands, a blind eye was cast upon the crimes these gifted men may have committed. As they went about building jets and rockets and high-performance aircraft, any sticky questions were made to disappear. The dead were dead, the Cold War was turning hot, and it was a time for practicalities. America opened its arms to these men. They enjoyed barbecues and baseball. They tended gardens. They worked hard, and they got us to the moon.

The image Americans had of Wernher von Braun in the early days of the Space Race was that of an enthusiastic rocketeer, a genius. In a six-part series called Man in Space, which was made by Walt Disney and aired in 1955 on primetime television, cartoons about zero gravity appeared on the screen as von Braun cheerfully held up model rockets. He smiled and said that a space station could be built. It would be a floating city in the stars.

A few years later, von Braun launched America’s very first satellite. He made the cover of TIME magazine and was hailed as “America’s Missileman” for getting Explorer 1 up into the heavens. Von Braun’s problematic past with the SS and the Third Reich had been bleached clean. There was no mention of the tunnels, the V-2, or a ravine full of human ash at Dora-Mittelbau.

*

The Saturn V was monstrous. Colossal. It towered up thirty-six stories. And when it was filled with super-cooled fuel, it creaked and groaned like a living creature. It strained for ignition. What made the Saturn V particularly special was its engines. They were a masterwork of design. Thanks to an elaborate twisting and coiling of metal, liquid oxygen cooled the engine bells and kept them from melting; it acted like icy fingers moments before being funneled into the pathway of kerosene, also known as RP-1. In a thrust chamber, these two volatile gases flashed into an inferno. Thus, the fuel itself was used to cool the engine bells hundredths of seconds before it became flame. It was ice then fire, coolant then propellant, a dance of chemicals. Von Braun knew that a great deal of weight was needed to go to the moon, and his Saturn V lifted it all into the stratosphere in less time than it takes you to load the dishwasher.

See it. Hear it. Feel it.

That’s how people in the viewing area described what it was like to watch a Saturn V lift off. First, there was a silent scorching orange plume from the launch pad, which was quickly followed by mighty shockwaves that rippled across the swampy waters of the Kennedy Space Center. Birds fell dead from the sky. Crackling thunder filled the air. A moment later, reverberations hit people’s chests. Neckties vibrated. Quarters and dimes jingled in back pockets. Bracelets danced. And as the rocket continued to climb, it got louder and louder. People had to plug their ears.

Compared to that, the V-2 was little more than a bottle rocket.

*

Today, rusted out parts of V-2s are still buried in the tunnels of Dora-Mittelbau, and an entire Saturn V in pristine condition is on display at the Kennedy Space Center. Wernher von Braun was in charge of both. But who thinks of the Dora camp when stock footage of a Saturn V lifts off for the moon? As the letters U…S…A trail before the camera, who wants to be reminded that the ghostly blueprint of a Nazi V-2 lives in the genes of America’s most famous rocket?

As for Dora, little remains of the camp today. Few people come to walk the grounds or climb the low hill up to the crematorium. The chimney, however, once roared with fire. At night, hellish flames once spilled up to the stars and, as they did so, the plume must have looked like an inverted rocket, a V-2 turned upside down. The building rumbled with the fuel of flesh and bone.

The camp was torn down by the Soviets after the war, because they needed the barracks elsewhere to house the homeless. They blew up the tunnel entrances to keep adventure seekers out. In 1995, the German government dug into the Kohnstein so that visitors could see the underground factory deep beneath the mountain with their own eyes. Inside, it is dark, cold, and littered with rusty debris. Although the water table has risen and flooded several areas, it is still possible to see painted numbers on the walls. Several desks, smashed toilets, and engine nozzles can be seen in the cone of a flashlight. Everything is waste and rubble and twisted metal. At this very moment, rusting parts of V-2s are hiding in the dark.

Also at this very moment, there are undisturbed boot prints on the surface of the moon. They are up there, dusty, powdery, and bathed in perpetual sunlight. The American flag planted by Apollo 17, the very last mission to the moon, has been bleached white by the never-ending glare of the sun.

To some people, the Holocaust and walking on the moon both seem impossible. It is easier to trust that human beings are not capable of such raw evil and such brave ingenuity. These people use the word “hoax”. They create elaborate reasons to undermine reality. It is no accident that some want to believe the two most profound events of the twentieth century never happened.

But they did happen. They both happened.

Their stories are not only about shadow and sunlight, but about who we are, and what we might become. These rockets we made can lift us up, or carry the payload of our undoing.

https://www.guernicamag.com/v-2-and-saturn-v-a-tale-of-two-rockets/ |

|

|

|

|

V2: el cohete nazi, la primera máquina que llegó al espacio

2 Sep 2021 | Blogs, Historia

El V2 fue diseñado para atacar a civiles y construido por esclavos, pero se convirtió en el punto de partida de la exploración espacial.

En el blog de hoy vamos a hablar sobre el cohete nazi V2 y toda la historia que hay detrás de él. El 3 de octubre de 1942, un trueno rasgó el cielo en una base secreta de la Alemania nazi, cerca de localidad de Peenemünde. Bajo la atenta mirada de un nutrido grupo de ingenieros y científicos, un cohete A-4 («Aggregat 4»), de 12 toneladas de peso, rugió y despegó de su plataforma. El artefacto se elevó con decisión hacia las alturas, como si estuviera suspendido por una fuerza fantasmal. El furioso motor, alimentado con alcohol etílico y oxígeno líquido, le hizo viajar 190 kilómetros y elevarlo hasta los 38 kilómetros de altura.

Wernher Von Braun, científico de las SS que lo desarrolló, se convirtió en héroe de Disney y de la NASA.

Europa estaba luchando en la Segunda Guerra Mundial cuando, sin que nadie lo sospechara, la carrera espacial dio su primer paso. Un 20 de junio de 1944 uno de estos cohetes A-4 atravesó la línea de Karmán, un límite situado a 100 kilómetros de altura, y llegó al espacio exterior, por primera vez en la historia. Pero su desarrollo no estaba motivado por el amor a la ciencia.

En septiembre de ese mismo mes, los nazis comenzaron a lanzar cohetes A-4 cargados con explosivos sobre ciudades como Lieja, Amberes y Londres para vengarse por los bombardeos aliados sobre las ciudades alemanas. Acababa de nacer el misil balístico y el A4 se había convertido en el V-2 o «Vergeltungswaffe 2», «Arma de la venganza 2». Su destino era matar y fue construido con mano de obra esclava en campos de concentración. Pero fue absolutamente crucial en el desarrollo de los cohetes espaciales. La prueba más directa es que su desarrollador, el ingeniero alemán Wernher Von Braun, fue también el «héroe» de los Estados Unidos de América que diseñó el cohete que llevó al hombre a la Luna.

Los pioneros del espacio comenzaron su labor haciendo la guerra

Los principales diseñadores del cohete soviético «R-7», que puso en órbita el Sputnik, el primer satélite artificial, diseñaron aviones de combate y lanzacohetes durante la contienda mundial. En los Estados Unidos, decenas de científicos del régimen nazi permitieron que el hombre llegara a la Luna con el programa Apolo.

Y antes de eso, durante los años treinta, el recién nacido Laboratorio Aeronáutico Guggenheim en el Caltech (GALCIT) trabajó en aplicaciones militares para los misiles antes de convertirse en el famoso Laboratorio de Propulsión a Chorro (JPL), en 1944. La propia NASA, hoy el emblema de la exploración espacial, nació en 1958 con el objetivo de luchar contra el aplastante dominio soviético del espacio.

El punto de partida de las primeras naves espaciales es el misil de guerra alemán V2. Este cohete fue fruto del trabajo de Herman Oberth y, sobre todo, de un joven físico llamado Wernher Von Braun. Este último encontró en el régimen nazi un medio para financiar y trabajar en el desarrollo de los cohetes. Von Braun, que ostentó un cargo en las SS, estuvo al frente de la parte tecnológica en la base secreta de Peenemünde y fue crucial para el éxito de los primeros diseños. Su impresionante labor le convirtió en la posguerra en un científico clave en el programa Apolo.

V2: El arma de la venganza

Con sus 14 metros de altura y su potente motor, el V2 era capaz de transportar una carga de 1.000 kilogramos de explosivo a 300 kilómetros de distancia. Tenía giroscopios para controlar el rumbo, con una escasa precisión que mejoró a medida que avanzó la guerra. Sin embargo, volaba tan rápido que resultaba imposible de interceptar para los medios de la época: alcanzaba velocidades de hasta 5.760 kilómetros por hora y podía impactar a casi 3.000 km/h.

Tal como explica Javier Casado Pérez en «Historia y Tecnología de la Exploración Espacial», el mal desarrollo de la guerra llevó a Hitler a ordenar la producción en masa de los cohetes V2. Desde septiembre de 1944 hasta la capitulación final, los alemanes construyeron más de 10.000 cohetes V2. De las cuales 2.676 cayeron sobre ciudades aliadas provocando el pánico y la muerte de 9.000 personas.

El importante papel de Wernher Von Braun

Después de que los nazis transportaran la producción de cohetes a las factorías subterráneas a causa de los bombardeos de los Aliados, Von Braun se quedó en Peenemünde a cargo de las pruebas y la investigación de cohetes.

En ese tiempo coordinó los trabajos para mejorar el V2 y para realizar nuevos diseños de naves más pesadas. Se elaboraron los planos de un nuevo cohete de dos etapas llamado «America», por su capacidad teórica de llegar a una autonomía de 4.800 kilómetros y de bombardear ciudades como Nueva York. Por fortuna, el diseño no llegó a abandonar los planos. Además, los nazis lograron romper la barrera del sonido con un misil equipado con alas y más tarde diseñaron dos cohetes aún mayores diseñados para poner cargas en órbita. Y que ya en los cincuenta, después de la guerra, serían esquemas básicos sobre los que Von Braun propuso la construcción de una estación espacial.

En marzo de 1944, la compleja relación entre Von Braun y las SS llevó a que el físico fuera arrestado por la Gestapo, la policía secreta del régimen nazi. Entonces, se le acusó de que su principal interés en desarrollar la V2 fue usarla como nave espacial y no como arma- Además, se sugirió que tenía planes de huir y entregarle planos secretos a los Aliados. Sin embargo, el crucial papel de Von Braun en la guerra hizo que fuera rápidamente liberado para continuar sus trabajos.

Acorazado Bismarck, apasionados de la historia

Desde la web Acorazado Bismarck nos consideramos unos apasionados por la historia y, sobre todo, por la relacionada con las grandes contiendas mundiales. Recordamos que no pretendemos hacer apología del nazismo en ningún momento. Solo nos gusta repasar los acontecimientos históricos que tuvieron lugar y hablar sobre el coleccionismo militar. Para más información, consulta aquí.

https://acorazadobismarck.es/2021/09/02/v2-el-cohete-nazi-la-primera-maquina-que-llego-al-espacio/ |

|

|

|

|

Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( VUR-nər von BROWN; German: [ˌvɛʁnheːɐ̯ fɔn ˈbʁaʊ̯n]; 23 March 1912 – 16 June 1977) was a German-American aerospace engineer[3] and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, the leading figure in the development of rocket technology in Nazi Germany, and later a pioneer of rocket and space technology in the United States.[4]

As a young man, von Braun worked in Nazi Germany's rocket development program. He helped design and co-developed the V-2 rocket at Peenemünde during World War II. The V-2 became the first artificial object to travel into space on 20 June 1944. Following the war, he was secretly moved to the United States, along with about 1,600 other German scientists, engineers, and technicians, as part of Operation Paperclip.[5] He worked for the United States Army on an intermediate-range ballistic missile program, and he developed the rockets that launched the United States' first space satellite Explorer 1 in 1958. He worked with Walt Disney on a series of films, which popularized the idea of human space travel in the U.S. and beyond from 1955 to 1957.[6]

In 1960, his group was assimilated into NASA, where he served as director of the newly formed Marshall Space Flight Center and as the chief architect of the Saturn V super heavy-lift launch vehicle that propelled the Apollo spacecraft to the Moon.[7][8] In 1967, von Braun was inducted into the National Academy of Engineering, and in 1975, he received the National Medal of Science.

Von Braun is a highly controversial figure widely seen as escaping justice for his Nazi war crimes due to the Americans' desire to beat the Soviets in the Cold War.[9][10][4] He is also sometimes described by others as the "father of space travel",[11] the "father of rocket science",[12] or the "father of the American lunar program".[9] He advocated a human mission to Mars.

Work under Nazi regime

In 1932, von Braun received a Bachelor of Science Degree in Mechanical Engineering from Technische Hochschule Berlin (now Technische Universität Berlin), Germany. During a period in 1931, von Braun attended the ETH Zürich in Switzerland. During this time in Switzerland, von Braun assisted Professor Hermann Oberth in writing a book concerning the possibilities of creating and manufacturing liquid-propellant rockets. Shortly after this, von Braun founded his own private rocket development business in Berlin, and through which made the first rocket fired by gasoline and liquid oxygen.[32]

In 1932, having caught wind of von Braun's rocket business, the German Army connected with von Braun to pursue basic missile research and weather data experimentation.[32] Von Braun said that the German government financed the development of test stands and facilities for experimentation in Darmstadt, Germany. In 1939, von Braun was appointed a technical advisor at Peenemünde Army Research Center on the Baltic Sea.[32]

First rank, from left to right, General Walter Dornberger (partially hidden), General Friedrich Olbricht (with Knight's Cross), Major Heinz Brandt, and Wernher von Braun (in civilian dress) at Peenemünde, Province of Pomerania, in March 1941

In 1933, von Braun was working on his creative doctorate when the Nazi Party came to power in a coalition government in Germany; rocketry was almost immediately moved onto the national agenda. An artillery captain, Walter Dornberger, arranged an Ordnance Department research grant for von Braun, who then worked next to Dornberger's existing solid-fuel rocket test site at Kummersdorf.[39]

Von Braun received his doctorate in physics (aerospace engineering) on 27 July 1934, from the University of Berlin for a thesis titled "About Combustion Tests." His doctoral supervisor was Erich Schumann.[28]: 61 However, this thesis represented only the public aspect of von Braun's work. His actual thesis, entitled "Construction, Theoretical, and Experimental Solution to the Problem of the Liquid Propellant Rocket" (dated 16 April 1934), detailed the construction and design of the A2 rocket. It remained classified by the German army until its publication in 1960.[40][41] By the end of 1934, his group had successfully launched two liquid fuel A2 rockets that rose to heights of 2.2 and 3.5 km (2 mi).[42]

Von Braun continued his guided missile work throughout World War Two, and met with Adolf Hitler on several occasions, being formally decorated by Hitler twice, including being awarded the Iron Cross.[43]

At the time, Germany was highly interested in American physicist Robert H. Goddard's research. Before 1939, German scientists occasionally contacted Goddard directly with technical questions. Von Braun used Goddard's plans from various journals and incorporated them into the building of the Aggregat (A) series of rockets. The first successful launch of an A-4 took place on 3 October 1942. The A-4 rocket became well known as the V-2.[45] In 1963, von Braun reflected on the history of rocketry, and said of Goddard's work: "His rockets ... may have been rather crude by present-day standards, but they blazed the trail and incorporated many features used in our most modern rockets and space vehicles."[24]

Goddard confirmed his work was used by von Braun in 1944, shortly before the Nazis began firing V-2s at England. A V-2 crashed in Sweden and some parts were sent to an Annapolis lab where Goddard was doing research for the Navy. If this was the so-called Bäckebo Bomb, it had been procured by the British in exchange for Spitfires; Annapolis would have received some parts from them. Goddard is reported to have recognized components he had invented and inferred that his brainchild had been turned into a weapon.[46] Later, von Braun said: "I have very deep and sincere regret for the victims of the V-2 rockets, but there were victims on both sides...A war is a war, and when my country is at war, my duty is to help win that war."[3]: 351

The engineer who designed the V2, Wernher von Braun, came to be feted as a hero of the space age. The Allies realised that the V-2 was a machine, unlike anything they had developed themselves.

—V-2: The Nazi rocket that launched the space age, BBC, September 2014.[47]

In response to Goddard's statements, von Braun said "at no time in Germany did I or any of my associates ever see a Goddard patent". This was independently confirmed. He wrote that statements that he had lifted Goddard's work were the furthest from the truth, noting that Goddard's paper "A Method of Reaching Extreme Altitudes", which was studied by von Braun and Oberth, lacked the specificity of liquid-fuel experimentation with rockets. It was also confirmed that he was responsible for an estimated 20 patentable innovations related to rocketry, as well as receiving U.S. patents after the war concerning the advancement of rocketry. Documented accounts also stated he provided solutions to a host of aerospace engineering problems in the 1950s and 1960s.[48]

Schematic of the A4/V2

On 22 December 1942, Adolf Hitler ordered the production of the A-4 as a "vengeance weapon", and the Peenemünde group developed it to target London. Following von Braun's 7 July 1943 presentation of a color movie showing an A-4 taking off, Hitler was so enthusiastic that he personally made von Braun a professor shortly thereafter.[49]

By that time, the British and Soviet intelligence agencies were aware of the rocket program and von Braun's team at Peenemünde, based on the intelligence provided by the Polish underground Home Army. Over the nights of 17–18 August 1943, RAF Bomber Command's Operation Hydra dispatched raids on the Peenemünde camp consisting of 596 aircraft, and dropped 1,800 tons of explosives.[50] The facility was salvaged and most of the engineering team remained unharmed; however, the raids killed von Braun's engine designer Walter Thiel and Chief Engineer Walther, and the rocket program was delayed.[51][52]

The V-2 became the first artificial object to travel into space by crossing the Kármán line with the vertical launch of MW 18014 on 20 June 1944.[53]

|

|

|

Primer Primer

Anterior

5 a 19 de 19

Siguiente Anterior

5 a 19 de 19

Siguiente

Último

Último

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Todos los derechos reservados | |

|

|

Estragos causados por un misil V-2 en el barrio de Whitechapel, Londres, el 27 de marzo de 1945. El cohete mató a 134 personas

Estragos causados por un misil V-2 en el barrio de Whitechapel, Londres, el 27 de marzo de 1945. El cohete mató a 134 personas Wernher Von Braun, rodeado de los líderes nazis de los que dependieron los trabajos en la base secreta de Peenemünde

Wernher Von Braun, rodeado de los líderes nazis de los que dependieron los trabajos en la base secreta de Peenemünde Misil V-2 en la actualidad

Misil V-2 en la actualidad Trabajadores esclavos trabajando en un misil V-2

Trabajadores esclavos trabajando en un misil V-2