|

|

General: ORIGIN OF THE KNIGHTS TEMPLARS FRENCH KNIGHT NAMED HUGUES DE PAYENS CATHOLIC

Scegli un’altra bacheca |

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 1 di 3 di questo argomento |

|

https://historycollection.com/the-origins-and-birth-of-the-united-states-marine-corps/#the-marines-first-action-and-aftermath

The Key to the Lost Treasure of the Knights Templar Could be Hidden in Canada

Trista - February 7, 2019

The Knights Templar is an almost legendary group of warrior monks whose story has colored many cultural tales. They are referenced in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, as well as The Da Vinci Code. Some people claim that the Freemasons – who lie at the heart of many conspiracy theories throughout history – have their origins in the Knights Templar. Others believe that they found a mysterious treasure at the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem during the Crusades. Their story is filled with so much intrigue, along with speculation, that separating fact from fiction can be a challenge.

During the Crusades, this band of warrior monks protected Christian pilgrims from Europe on the way to the Holy Lands. In the process, they established one of the world’s first banking systems. The way that it worked is a European nobleman would sell off some of his property to the order before embarking on a pilgrimage. An accountant in the order would issue him a deed, akin to a receipt, saying how much money he had “in his account.” As he made his journey to the Holy Land, when he stopped at an inn run by the knights, he could present his deed, along with a form of identification, and thus pay for services.

A drawing of one of the Templar Knights. Borstnar.

In the Holy Lands, they were like the Delta Force of the Crusades. They were the first standing army since the fall of the Roman Empire. Many crusaders were hordes of peasants and farmers who took up arms at the behest of the pope and their local leaders. They were not trained in warfare and often had nothing but their own religious fervor to guide their fighting. The Templars, though, were highly trained warriors who were experts in battle. Their services – as bankers, as hospitallers (for their hospitality), and as warriors – became highly valued.

In exchange for protecting Christian pilgrims traveling to Jerusalem, the Order of the Knights Templar was able to gain power, prestige, and vast amounts of wealth that made the organization one of the strongest in all of Europe. Members were effectively exempt from local laws because they were answerable only to the pope. They became so powerful, in fact, that they were seen as a threat to some kings, particularly King Philip of France, who ruled at the beginning of the fourteenth century. When he brought the order to its knees in 1307, and the pope later banned them, they didn’t disappear. They are still alive in many people’s imaginations today.

A drawing of a group of Templars. Ancient Origins.

Of all the mystery that surrounds the order, one of the most enduring legends of the Knights Templar is that of their treasure. What exactly did it consist of, and what happened to it? Did it exist at all, or was it a fabrication invented by nobles to have a reason to degrade the knights? One of the most intriguing theories is that the treasure lies hidden deep underground in a remote island off the coast of Nova Scotia: Oak Island.

A representation of a Knight Templar (Ten Duinen Abbey museum, 2010). Photo by JoJan CC BY 3.0/The Vintage News.

Origin of the Knights Templar

The organization that came to be known as the Knights Templar began about 23 years after the First Crusade when Christian warriors from Europe seized Jerusalem. Many European Christians wanted to make a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, but the journey was long and dangerous, as travelers were often robbed by bandits. A French knight named Hugues de Payens obtained approval from the pope to form an organization that would protect pilgrims who were traveling to and from the Holy Land. The pope granted him permission, and a small cohort of nine warrior monks, led by de Payens, began their mission by traveling to Jerusalem.

Once in Jerusalem, they made the Temple Mount their headquarters. The Temple Mount refers to the place on which King Solomon built his legendary temple to Yahweh, which housed the Ark of the Covenant and the presence of God. The temple was pillaged in the sixth century BCE, then rebuilt by King Herod in the first century. It was ruined in 70 AD. Many people believe that before it was destroyed in the sixth century BCE, King Solomon’s treasure was hidden somewhere inside. Before the second destruction, even more treasures, particularly from the life of Jesus Christ, may have been buried. Rumors spread that the Knights Templar were at the Temple Mount because they intended to recover the lost treasures.

Map of Oak Island, Nova Scotia. Photo by Oaktree CC BY-SA 4.0/ The Vintage News.

The Knights Templar went all but completely off the radar for a few years after they first arrived in Jerusalem. They weren’t protecting pilgrims on their way to Jerusalem, as their original charter had stated. Many people believe that they were digging for treasure, particularly in the underground stables that housed the horses of King Solomon. Nobody knows for sure if they found any treasure, or if there are people who do know, they have been quiet about it for centuries.

One prevailing belief is that the Knights Templar found holy relics that enabled them to become particularly powerful. When they went back to Europe, 10 years after the order was first founded, they became very wealthy very quickly. Noblemen gave them large tracts of land, and the pope even issued a papal bull that said that the warrior monks were accountable only to the Vatican. They could not be prosecuted by any state institutions. Speculation over how they gained so much wealth and prestige so quickly, going from obscurity to notoriety virtually overnight, has led to numerous theories, particularly about their alleged treasure.

A drawing of a Templar Knight on horseback. Anonymous Radio Show.

Not everyone was pleased with the prestige of the Knights Templar. On Friday the 13th of 1307, King Philip of France rounded up all of its members. He tortured and executed many of them, but quite a few probably escaped. Some Templar ships that were docked off the coast of France disappeared the night before the roundup. One particularly prominent belief is that members of the Knights Templar carried off their wealth on these ships. Nobody knows exactly where the treasure went. There are plenty of theories, though, yet none of them have been proven.

Island and Wharf, Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada, August 1931. The Vintage News.

The Treasure of the Knights Templar

While one can only speculate about what the treasure of the Knights Templar actually was, theories abound as to where it was hidden. One of the most pervasive assumptions is that it is buried deep underneath Oak Island in Nova Scotia, Canada. What makes this theory so compelling yet incredible is that Oak Island is far from France, from where the treasure was supposedly secreted away. The knights who survived the Friday the 13th massacre would have had to carry it all the way across the Atlantic Ocean, only hoping that they would find land on the other side.

The theory begins with the idea that the knights first carried the treasure up to Scotland, where they would find greater freedom, especially in light of laws there that allowed for greater freedom of religion. Some believe that those that stayed behind in Scotland were behind the construction of the mysterious Rosslyn Chapel, a Medieval church that lies a few miles south of the capital city, Edinburgh. To protect the treasure, some knights carried it first to Iceland, then on to Greenland, and finally to Nova Scotia, Canada. If the theory holds, then the Knights Templar may have preceded Christopher Columbus to the New World by over a century.

A photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt and others at Oak Island in Nova Scotia. The Vintage News.

According to local legend, Daniel McGinnis, the first recorded settler on Oak Island, found a depression in the earth while surveying land for a farm in 1799. People claimed that Captain Kidd had buried his treasure there. A furious treasure hunt began, where several people lost their lives. However, there is no real evidence that treasure hunting began on Oak Island until the mid-nineteenth century. And there is no evidence that Captain Kidd buried treasure there. If anything, the evidence suggests that any treasure on Oak Island was from the Templars.

What the treasure hunters discovered is a pit that, at ten-foot intervals, had shafts made of either logs or flagstones. Clearly, someone had already visited Oak Island and dug the hole intentionally and with great care, presumably to bury a treasure of great value. In the time since the pit’s discovery, investors have put so much money into finding what lies hidden in it that it has come to be known as the “money pit.” Several people have died trying to find what lies at the bottom of the pit, leading to what some call “the curse of Oak Island,” rather than the treasure.

Symbols and icons found near the pit indicate the possibility of a Templar presence. Combined with the mystery and intrigue surrounding the group’s disappearance in Europe in the fourteenth century, many believe that the theory of the Templars burying their treasure at Oak Island is entirely plausible. If that is the case, then things like the Ark of the Covenant and the Holy Grail, along with other mysterious relics and artifacts that the Templars uncovered at Solomon’s Temple, may indeed be buried at Oak Island.

Where did we find this stuff? Here are our sources:

“Secrets of the Knights Templar.” The History Channel.

“Who were the Knights Templar?” by Elizabeth Nix. The History Channel. October 17, 2012.

“Hugue de Payens.” Wikipedia.

“Oak Island.” Wikipedia.

The Origins and Birth of the United States Marine Corps

Khalid Elhassan - February 6, 2019

The US Marines’ Historical Predecessors

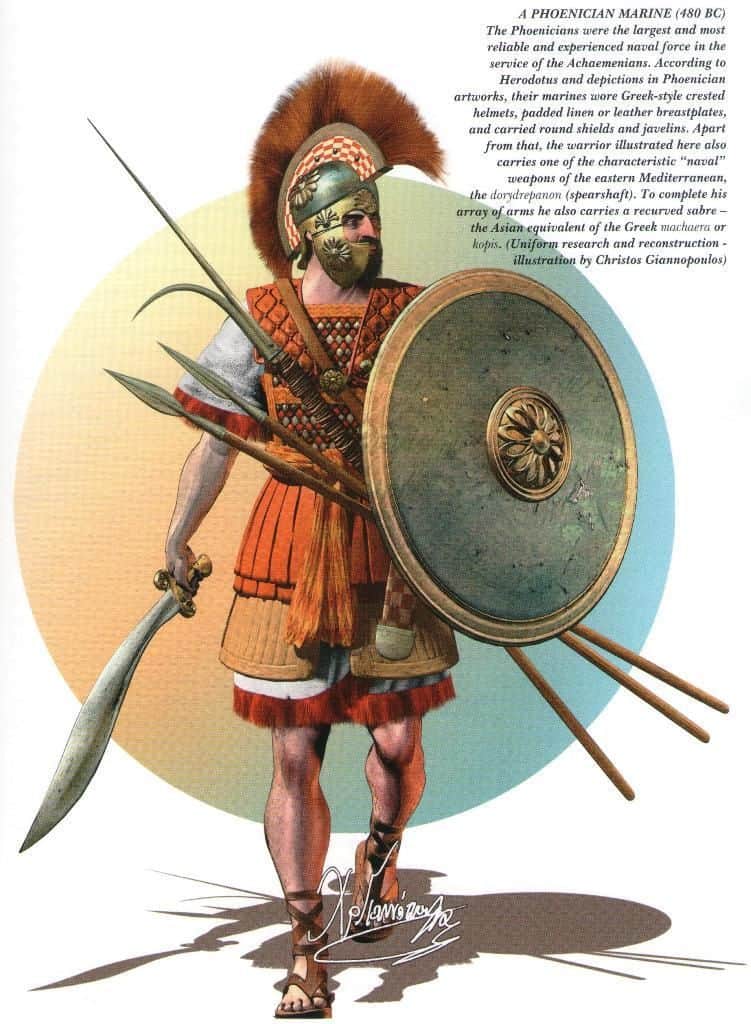

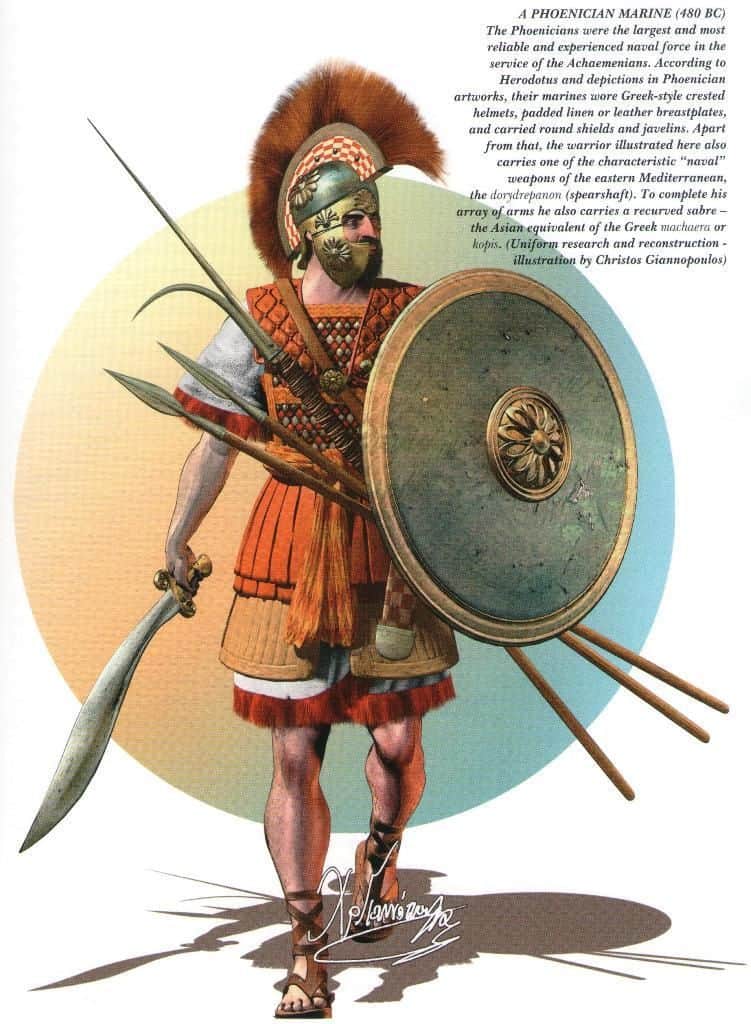

Ship borne infantry that specializes in supporting naval operations, otherwise known as naval infantry or marines, have been around for thousands of years. In the early days of naval warfare, sailors doubled as soldiers in a pinch, until the ancient Phoenicians introduced complements of soldiers whose primary tasks were not the care, maintenance, and operation of ships. Instead, the duties of these specialists revolved primarily around boarding enemy ships and warding off enemy boarders from their own vessels, or conducting amphibious operations by disembarking to attack and raid targets on land, then returning to their vessels.

Before long, others around the Mediterranean basin began copying the Phoenicians, and took to employing their own ship borne infantry. By the late 6th century BC, marines were a common feature in the Eastern Mediterranean. The ancient Greeks took the idea and ran with it, and as early as the 5th century BC, they began introducing heavily armed and armored hoplites on their triremes for the specific purpose of boarding enemy vessels. The Athenians, in particular, refined the concept, and built themselves a sea empire around the Aegean and Black Sea, with marines playing an integral role in their naval strategy and tactics.

Ancient Phoenician marine. Pintrest

The Romans – who learned the concept from both the Greeks and Carthaginians against whom they fought protracted wars – developed and took naval infantry even further. Landlubbers, the Romans were excellent soldiers but poor sailors, and they discovered during the First Punic War (264 – 241 BC) that they were no match for the highly experienced Carthaginians in seamanship and naval tactics. So they hit upon the innovative idea of transforming naval engagements into de facto land battles. The Romans accomplished that by modifying their ships with a device called a corvus (crow), that was basically a plank on a pivot with a heavy metal beak, that was dropped on an enemy vessel when it drew near, penetrating its deck and securing it to the Roman ship. Roman naval infantrymen – Marinus – would then cross over the plank, slaughter the enemy sailors and rowers, and capture the ship.

In the middle ages, the Venetians, masters of a maritime trade empire that would eventually capture and sack Constantinople in 1204, then go on to rule Byzantium for over half a century, created a well organized marine corps. Known as the Fanti da Mar (sea infantry), the Venetian marines were comprised of 10 companies, that could be combined to form a marine regiment that supported naval operations with amphibious landings and ship borne combat.

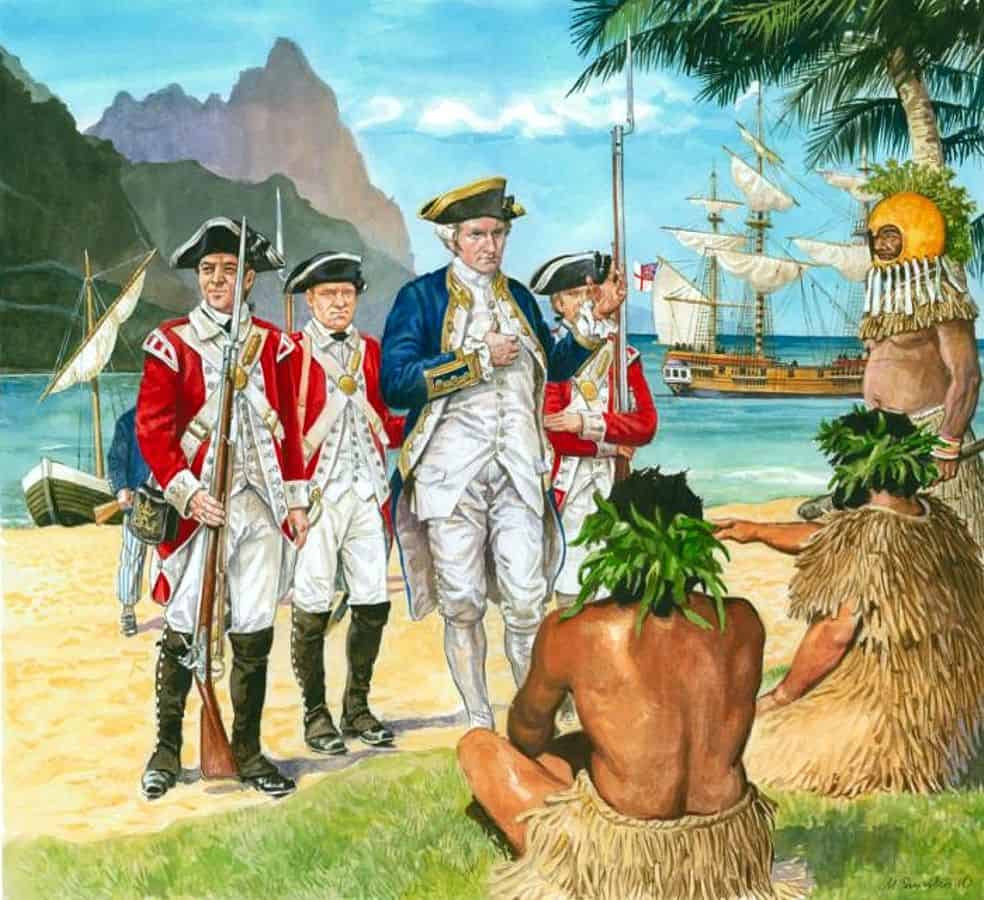

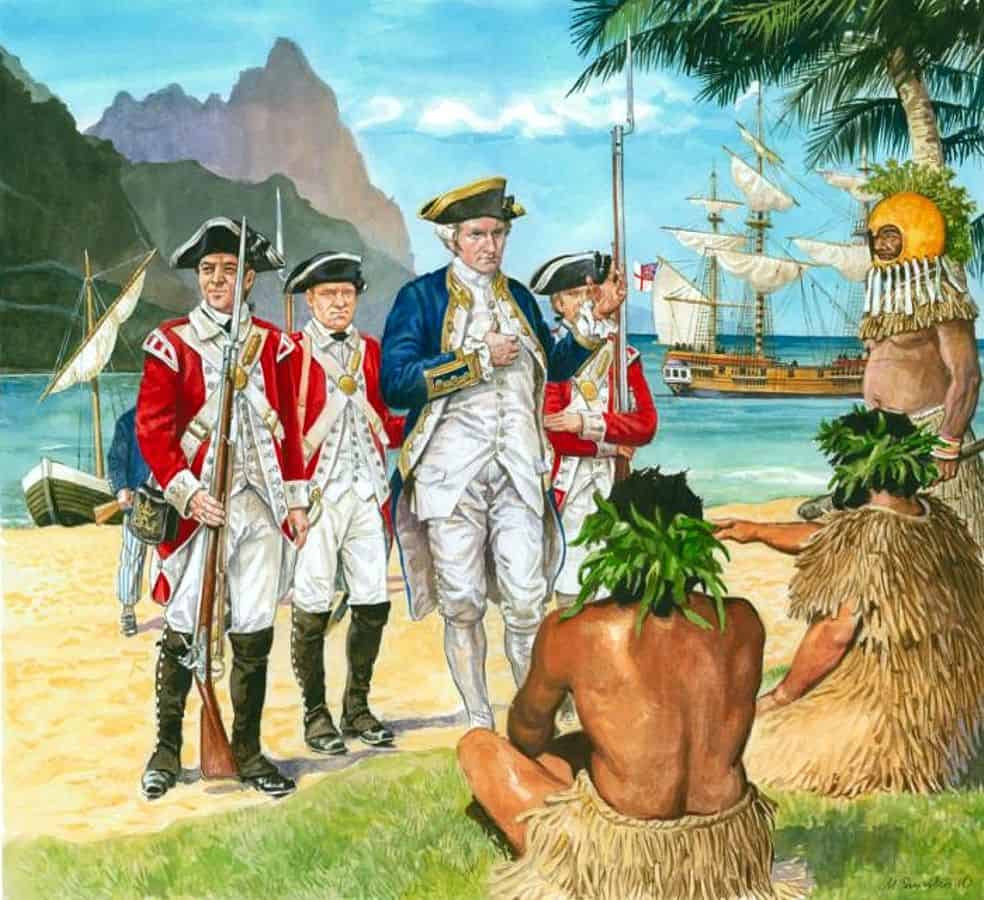

British Royal Marines accompanying captain Cook as he talks with South Sea islanders. Pintrest

During the Age of Exploration, the Spanish, masters of the world’s first far flung global empire upon which the sun literally never set, formed the Spanish Marine Infantry in 1537 – the oldest marine corps still in existence. Other European naval powers followed suit, including the British, whose Royal Marines – the model upon which the Americans would draw a century later, when forming the naval infantry that eventually became the United States Marine Corps – can trace their origins back to 1664.

By the 18th century, naval service, particularly in the British Royal Navy, often entailed long voyages that could last for years. Living conditions aboard ship were often abysmal, and the crews included many sailors who had been forcibly press ganged into serving king and country. As Winston Churchill described it, life in the Royal Navy back then boiled down to “rum, buggery, and the lash“. That led to an evolution in the role of marines: in addition to their traditional functions, the marines now also served as the captain’s armed muscle aboard ship. Quartered apart from and treated differently than the rest of the crew, marines kept the often brutalized and miserable sailors in check, preventing them from rising up in mutiny and murdering their officers.

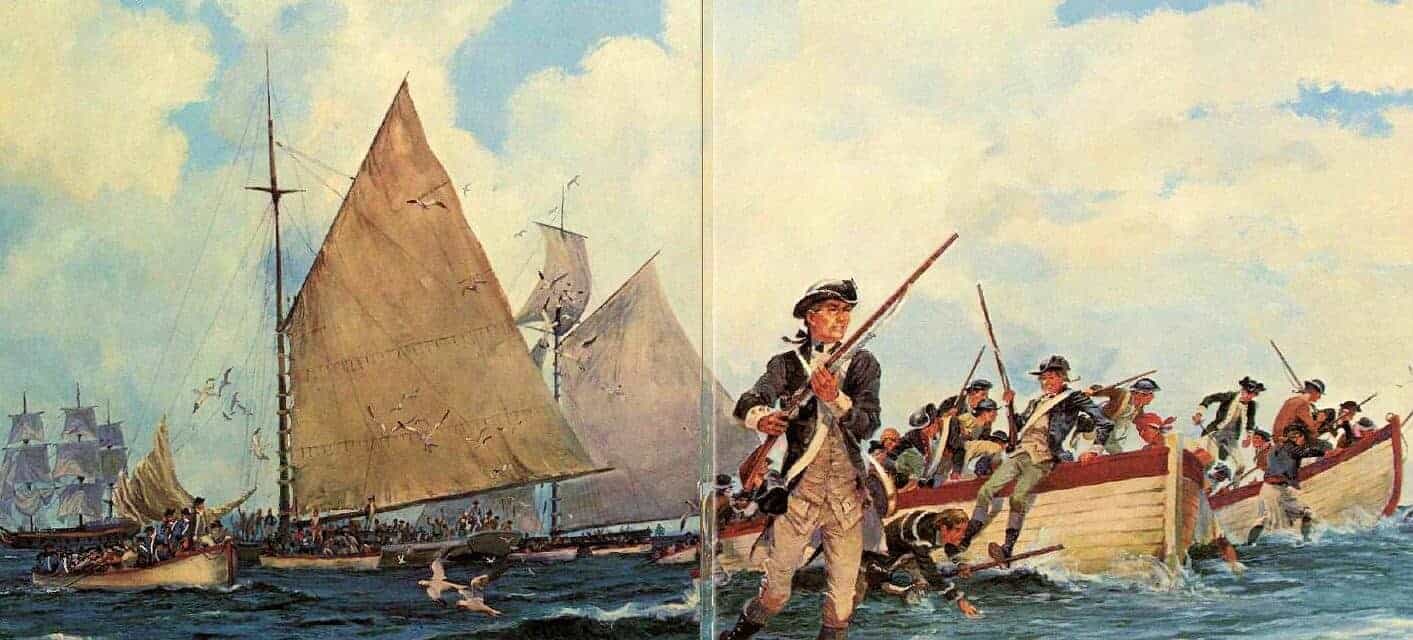

Revolutionary war marines. Weapons and Warfare

The Continental Marines

Marines were first raised in America during the War of Jenkins Ear (1739 – 1742), when the British Admiralty recruited a naval infantry regiment of 3000 men from the American colonies for a campaign against Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and South America. The result was a four battalion unit commonly known as “Gooch’s Marines”, after a Virginia governor named William Gooch, who raised and led the outfit. A dumping ground for criminals, debtors, and vagrants, Gooch’s Marines served credibly for the most part around the Caribbean. However, between tropical diseases and a disastrous attack against Cartagena, in today’s Colombia, the unit lost over 90% of its men by the time it was disbanded at war’s end in 1742.

When the American Revolution broke out, some American colonies’ militias formed their own marine contingents. Most prominent among those marine militia was Massachusetts’ Marblehead Regiment, formed in January of 1775 from seafaring men from the region around Marblehead, Massachusetts. Folded into the Continental Army in the summer of 1775, and reorganized as the 14th Continental Regiment early the following year, it served George Washington as an ad hoc marine unit, especially during his 1776 New York Campaign.

In the meantime, the Continental Congress decided to raise a marine unit, and on November 10th, 1775 a resolution drafted by future president John Adams was approved. It directed in relevant part: “That two Battalions of marines be raised, consisting of one Colonel, two Lieutenant Colonels, two Majors, and other officers as usual in other regiments; and that they consist of an equal number of privates with other battalions; that particular care be taken, that no persons be appointed to office, or enlisted into said Battalions, but such as are good seamen, or so acquainted with maritime affairs as to be able to serve to advantage by sea when required; that they be enlisted and commissioned to serve for and during the present war between Great Britain and the colonies, unless dismissed by order of Congress“.

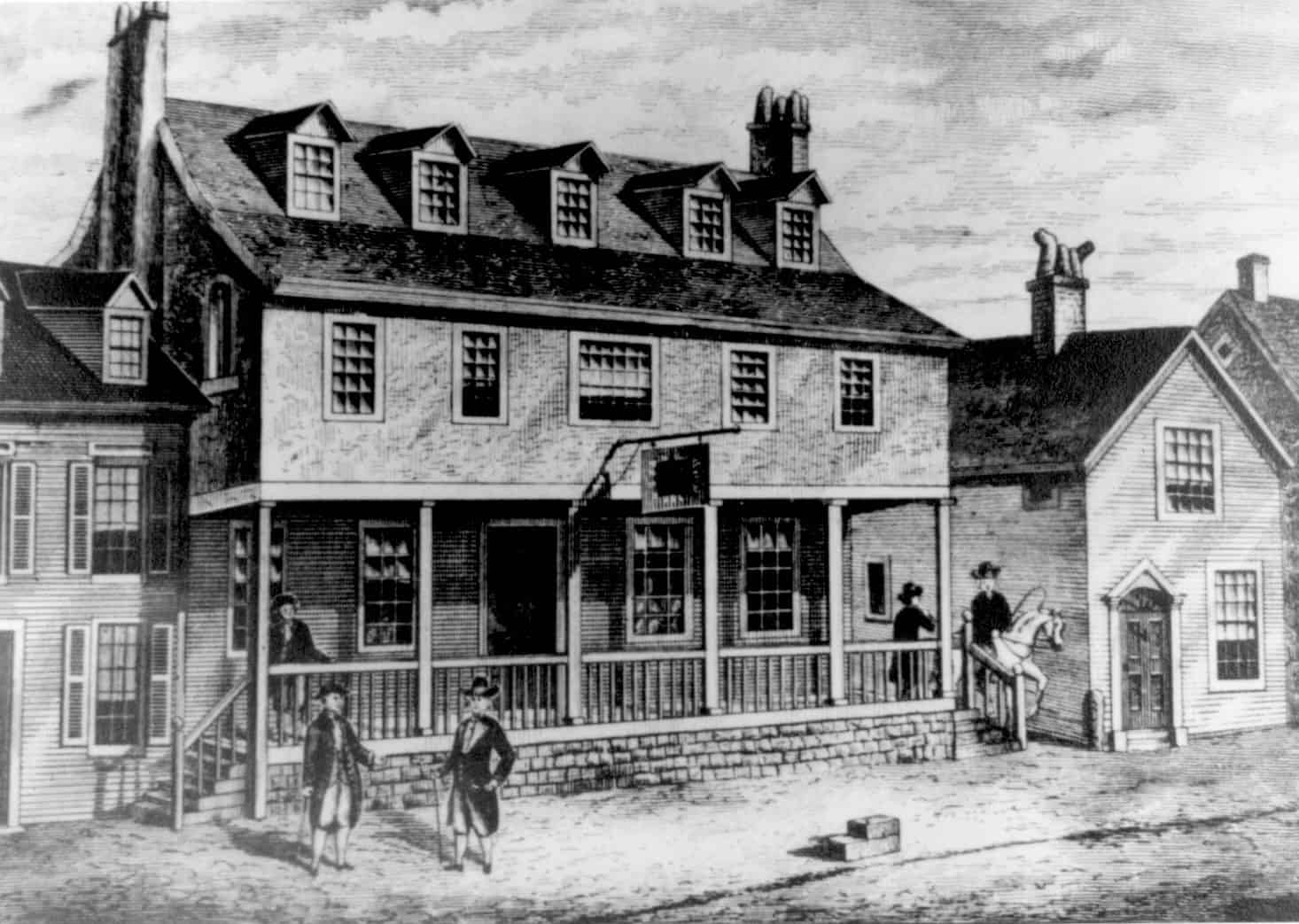

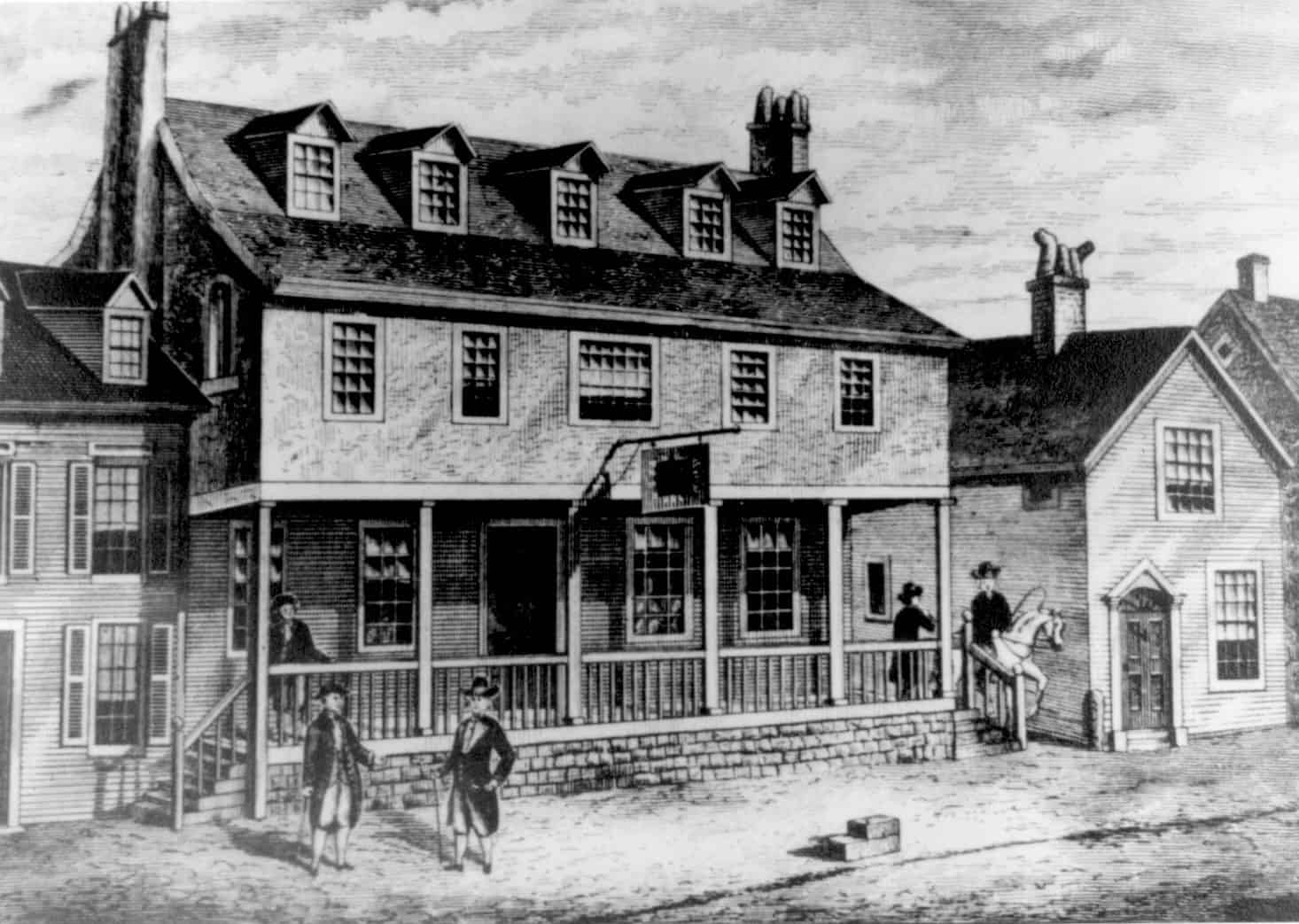

Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, birthplace of the United States Marine Corps during the Revolutionary War. Wikimedia

November 10th is celebrated to this day as the birthday of the United States Marine Corps. To implement the congressional directive, a Pennsylvania captain named Samuel Nicholas set up a recruiting headquarters in Tun Tavern, on Water Street in Philadelphia, which is considered the birthplace of the US Marines. Tun Tavern was a successful establishment with a reputation for serving fine beer, and Captain Nicholas appointed its owner, Robert Mullan, to serve as his chief Marine recruiter.

A good pitch and a good pitcher of beer go well together, and within weeks, enough Marines had been recruited to man the Continental Navy’s ships in the waters off Philadelphia. On January 4th, 1776, less than two months after the congressional directive that ordered the Continental Marines into being, Captain Nicholas and his naval infantry set sail. Two months later, Nicholas and his Continental Marines would have their baptism of fire at the Battle of Nassau, in the Bahamas.

Continental Marines, circa 1777. Pintrest

The Marines’ First Action and Aftermath

The Continental Marines’ first combat operation came about because the Continental Army was hard pressed for gunpowder. Its recently appointed commander in chief, general George Washington, had asked Congress for 400 barrels of gunpowder, but his political masters responded by sending him fewer than 40 barrels – barely enough for 20 rounds per soldier. Despite Washington’s repeated remonstrations, pleas, and threats of impending disaster if his forces were not adequately supplied, no more gunpowder was forthcoming. So alternatives were sought, and it was decided that if Congress could not provide what was needed, perhaps the British would.

Virginia’s colonial governor, Lord Dunmore, had removed his colony’s stores of weapons and munitions – including gunpowder – to Nassau, New Providence Island, in the Bahamas, when the Revolutionary War erupted, to secure them against capture by the rebels. When word arrived that there were over 200 barrels of gunpowder stored in the Bahamas, Congress directed the commander of the recently established Continental Navy, Esek Hopkins, to raid the British stores and seize the desperately needed munitions. The ensuing naval operation and amphibious assault was to be the first significant engagement of the new Navy and Marines.

On February 17th, 1776, Esek Hopkins sailed from Delaware to the Bahamas with a small fleet of eight ships, accompanied by a contingent of Continental Marines under the command of captain Samuel Nicholas. Stormy weather forced two of Hopkins’ ships to turn back, but he sailed on with his remaining six vessels, finally reaching New Providence Island on March 1st. There, he promptly captured two British merchantmen off Nassau, replacing the two ship he had lost on the way there. Then, for reasons lost to history, Hopkins kept his ships anchored offshore for two days, before finally landing a force of about 200 Marines and 50 sailors on the morning of March 3rd.

Fort Montagu in the Bahamas, the first fortification captured by an American marine amphibious landing. Fine Art America

By then, the defenders were aware that enemy vessels were operating in their waters, and when ships were spotted sailing in to Nassau, the alarm was raised. At the approach of the American forces, the outnumbered defenders evacuated Fort Montagu, one of two fortifications defending Nassau, and it was promptly occupied by captain Nicholas and his Continental Marines. Nicholas failed to continue on to and capture Nassau that day, however, and spent the night of the 3rd in Fort Montagu. That night, the British in Nassau loaded most of the gunpowder stored there – 162 barrels out 200 – aboard a ship, which managed to sneak out of the harbor and sail away to safety. The following morning, Nicholas and his men occupied Nassau, and seized the remaining 38 barrels of gunpowder, wrapping up the Continental Marines’ first major operation.

By war’s end, the Continental Marines had grown to over 2000 men. After America secured its independence in 1783, the Continental Navy was demobilized, and its Marines were disbanded. In subsequent years, however, tensions with European powers, particularly France, played out on the high seas, and America’s inability to protect its shipping or retaliate against aggression led Congress to formally reestablish the US Navy in May of 1798. Two months later, on July 11th, 1798, president John Adams signed into law a bill establishing the United States Marine Corps as a standing military force within the Department of the Navy.

_________________

Where Did We Find This Stuff? Some Sources and Further Reading

History – Birth of the US Marine Corps

Military – The Origins of the Marine Corps

Time Magazine, November 10th, 2015 – How the US Marine Corps Was Founded Twice

Varsity Tutors – The Continental Marines: The Birth of the Leathernecks

Wikipedia – History of the United States Marine Corps

Marine Corps University – Brief History of the United States Marine Corps

https://historycollection.com/the-origins-and-birth-of-the-united-states-marine-corps/#the-marines-first-action-and-aftermath |

|

|

Primo

Primo

Precedente

2 a 3 di 3

Successivo

Precedente

2 a 3 di 3

Successivo

Ultimo

Ultimo

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 2 di 3 di questo argomento |

|

|

|

|

Rispondi |

Messaggio 3 di 3 di questo argomento |

|

Hugo de Payns o Payens (castillo de Payns, cerca de Troyes, Francia 9 de febrero de 1070-Reino de Jerusalén, 24 de mayo de 1136) fue el fundador y primer maestro de los Caballeros templarios y uno de los primeros nueve caballeros. En asociación con Bernardo de Claraval, creó la Regla latina, el código de conducta de la Orden.

Hijo de Gautier de Montigny y nieto de Hugo I, Señor de Payns, su infancia y su juventud se ven influidas por el ambiente de reforma religiosa que se desarrolla en la Champaña y que dará figuras de la talla de san Roberto de Molesmes, fundador de las abadías de Molesmes y Cîteaux, o la de san Bernardo de Claraval, impulsor de la reforma del cister y mentor eclesiástico de la misma Orden del Temple.

De la ferviente pasión religiosa de Hugo II de Payns es muestra su breve paso como monje por la abadía de Molesmes, tras la muerte de su primera esposa Emelina de Touillon, con la que se había desposado hacia el 1090. Fruto de este matrimonio nació su hija Odelina, futura señora de Ervy.

Vasallo fiel del conde Hugo I de Champaña,1 Hugo II de Payns abandona los hábitos y a partir del año 1100 se integra plenamente como uno de los principales miembros de la Corte champañesa, uniendo en su persona el señorío de Montigny y el de Payns.

Es muy probable que Hugo II de Payns realizara su primer viaje a Tierra Santa junto al conde de Champaña en 1104-1107. Tras regresar de este, y para ayudar a consolidar las pretensiones políticas de su señor, casó en segundas nupcias con Isabel de Chappes (entre 1107 y 1111), perteneciente a una de las familias más importantes del sur de la Champaña. Del matrimonio nacieron cuatro hijos: Teobaldo, futuro Abad de Santa Colombe de Sens; Guido Bordel de Payns, heredero del señorío; Guibuin, vizconde de Payns, y Herberto, llamado el ermitaño. Sin embargo, la pasión religiosa que sentía le llevó a tomar votos de castidad en 1119 y a partir nuevamente a Tierra Santa, donde creó, un año más tarde, la que llegaría a ser la Orden Militar más importante de la Cristiandad: La Orden del Temple.

Se afirma[cita requerida] que los otros caballeros eran Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, Archambaudo de Saint Agnan, Andrés de Montbard (tío materno de San Bernardo de Claraval), Godofredo Bison, y otros dos de los que solo se conoce su nombre, Rolando y Gondamero. Se desconoce el nombre del noveno caballero, aunque hay quien piensa que pudo ser Hugo, conde de Champaña.

En 1127 Hugo II de Payns regresa a Europa acompañado por Godofredo de Saint-Omer, Payen de Montdidier, y dos hermanos más, de nombre Raúl y Juan, con el fin de reclutar nuevos miembros para la Orden, tomar posesión de las numerosas donaciones que habían sido otorgadas a esta y para organizar las primeras encomiendas de la Orden en Occidente (casi todas ellas en la región de la Champaña). Así pues, Hugo inicia un periplo que le lleva por Roma - a fin de solicitar del papa Honorio II un reconocimiento oficial de la Orden y la convocatoria de un concilio que debatiera el asunto - la Champaña (otoño de 1127); Anjou y Poitou (abril y mayo de 1128), Normandia, Inglaterra y Escocia (verano de 1128) y Flandes (otoño de 1128).

Hugo y sus compañeros regresan en enero de 1129 a la Champaña para tomar parte en el Concilio de Troyes, un concilio de la Iglesia católica, que se convocó en la ciudad francesa el 13 de enero de 1129, con el principal objeto de reconocer oficialmente a la Orden del Temple. En dicho concilio estuvieron presentes: el cardenal Mateo de Albano (representante del Papa); el arzobispo de Reims y el de Sens; diez obispos; ocho abades cistercienses de las abadías de Vézelay, Cîteaux, Clairvaux (que en este caso no era otro sino San Bernardo), Pontigny, Troisfontaines y Molesmes; y algunos laicos entre los que destacan Teobaldo II de Champaña, el conde de Campaña, André de Baudemont, el senescal de Champaña, el conde de Nevers y un cruzado de la campaña de 1095.

Hugo de Payns relató en este concilio los humildes comienzos de su obra, que en ese momento solo contaba con nueve caballeros, y puso de manifiesto la urgente necesidad de crear una milicia capaz de proteger a los cruzados y, sobre todo, a los peregrinos a Tierra Santa, y solicitó que el concilio deliberara sobre la constitución que habría que dar a dicha Orden.

Se encargó a San Bernardo, abad de Claraval, y a un clérigo llamado Jean Michel la redacción de una regla durante la sesión, que fue leída y aprobada por los miembros del concilio.

Tras el concilio de Troyes, Hugo II de Payns nombró a Payen de Montdidier Maestre Provincial de las encomiendas sitas en territorio francés y en flandes, y a Hugo de Rigaud Maestre Provincial para los territorios del Languedoc, la Provenza y los reinos cristianos hispánicos y tras ello, regresó a Jerusalén dirigiendo la Orden que el mismo había creado durante casi veinte años hasta su muerte en el año 1136 (el 24 de mayo según el obituario del templo de Reims), haciendo de ella una influyente institución militar y financiera internacional.

Un cronista del siglo XVI escribió que fue enterrado en la Iglesia de San Jaime de Ferrara.2

No hay un retrato contemporáneo de él.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

©2025 - Gabitos - Tutti i diritti riservati | |

|

|

A drawing of one of the Templar Knights. Borstnar.

A drawing of one of the Templar Knights. Borstnar.

A drawing of a group of Templars. Ancient Origins.

A drawing of a group of Templars. Ancient Origins.

A representation of a Knight Templar (Ten Duinen Abbey museum, 2010). Photo by JoJan CC BY 3.0/The Vintage News.

A representation of a Knight Templar (Ten Duinen Abbey museum, 2010). Photo by JoJan CC BY 3.0/The Vintage News.

Map of Oak Island, Nova Scotia. Photo by Oaktree CC BY-SA 4.0/ The Vintage News.

Map of Oak Island, Nova Scotia. Photo by Oaktree CC BY-SA 4.0/ The Vintage News.

A drawing of a Templar Knight on horseback. Anonymous Radio Show.

A drawing of a Templar Knight on horseback. Anonymous Radio Show.

Island and Wharf, Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada, August 1931. The Vintage News.

Island and Wharf, Oak Island, Nova Scotia, Canada, August 1931. The Vintage News.

A photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt and others at Oak Island in Nova Scotia. The Vintage News.

A photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt and others at Oak Island in Nova Scotia. The Vintage News.

Ancient Phoenician marine. Pintrest

Ancient Phoenician marine. Pintrest

British Royal Marines accompanying captain Cook as he talks with South Sea islanders. Pintrest

British Royal Marines accompanying captain Cook as he talks with South Sea islanders. Pintrest

Revolutionary war marines. Weapons and Warfare

Revolutionary war marines. Weapons and Warfare

Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, birthplace of the United States Marine Corps during the Revolutionary War. Wikimedia

Tun Tavern in Philadelphia, birthplace of the United States Marine Corps during the Revolutionary War. Wikimedia

Continental Marines, circa 1777. Pintrest

Continental Marines, circa 1777. Pintrest

Fort Montagu in the Bahamas, the first fortification captured by an American marine amphibious landing. Fine Art America

Fort Montagu in the Bahamas, the first fortification captured by an American marine amphibious landing. Fine Art America